Abstract

Objective

To investigate the salt (sodium chloride) content in cheese sold in UK supermarkets.

Study design

We carried out a cross-sectional survey in 2012, including 612 cheeses available in UK supermarkets.

Methods

The salt content (g/100 g) was collected from product packaging and nutrient information panels of cheeses available in the top seven retailers.

Results

Salt content in cheese was high with a mean (±SD) of 1.7±0.58 g/100 g. There was a large variation in salt content between different types of cheeses and within the same type of cheese. On average, halloumi (2.71±0.34 g/100 g) and imported blue cheese (2.71±0.83 g/100 g) contained the highest amounts of salt and cottage cheese (0.55±0.14 g/100 g) contained the lowest amount of salt. Overall, among the 394 cheeses that had salt reduction targets, 84.5% have already met their respective Department of Health 2012 salt targets.

Cheddar and cheddar-style cheese is the most popular/biggest selling cheese in the UK and has the highest number of products in the analysis (N=250). On average, salt level was higher in branded compared with supermarket own brand cheddar and cheddar-style products (1.78±0.13 vs 1.72±0.14 g/100 g, p<0.01). Ninety per cent of supermarket own brand products met the 2012 target for cheddar and cheddar-style cheese compared with 73% of branded products (p=0.001).

Conclusions

Salt content in cheese in the UK is high. There is a wide variation in the salt content of different types of cheeses and even within the same type of cheese. Despite this, 84.5% of cheeses have already met their respective 2012 targets. These findings demonstrate that much larger reductions in the amount of salt added to cheese could be made and more challenging targets need to be set, so that the UK can continue to lead the world in salt reduction.

Keywords: NUTRITION & DIETETICS, PUBLIC HEALTH

Video abstract

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This paper for the first time investigates the salt content in cheese products available in UK supermarkets.

This paper demonstrates the high salt content in cheese in the UK and the large variation in salt content between different types of cheeses and within the same type of cheese. The results indicate that much larger reductions in the amount of salt added to cheese could be made and more challenging targets need to be set.

This study was based on salt content data provided on cheese packaging labels in stores; hence we relied on the accuracy of the data provided on the label. Therefore, it is assumed that the manufacturers provide accurate and up-to-date information in line with European Union regulations.

Introduction

There is strong evidence that a high salt intake increases blood pressure and thereby increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (ie, strokes, heart attacks and heart failure) and kidney disease.1 2 A high salt intake also has other harmful effects on health, for example, increasing the risk of stomach cancer3 and osteoporosis,4 and is indirectly linked to obesity.5 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that a reduction in population salt intake is one of the most cost-effective measures to improve public health.6 Populations around the world are consuming salt in quantities that far exceed physiological requirements.7 As such, the WHO has recommended salt reduction as one of the top three priority actions to tackle the non-communicable disease crisis.8 At the recent World Health Assembly, it was unanimously agreed that all countries should reduce their salt intake by 30% towards a target of 5 g/day, by 2025.9

The UK has successfully developed a voluntary salt reduction programme which is considered one of ‘the most successful nutrition policies in the UK since the second world war’.10 First developed by Consensus Action on Salt & Health (CASH), the strategy involves lowering salt intakes by (1) reducing the amount of salt added to processed foods by 40% and (2) reducing salt in cooking or at the table by 40%. In order to reduce average salt intake from 9.5 g/day to the projected target of 6 g/day in adults, the Food Standards Agency (FSA) then set a series of progressively lower salt targets for over 80 categories of food,11 12 which have now been incorporated as part of the Government's Public Health Responsibility Salt Reduction Pledge as the ‘2012 targets’.13 Other countries around the world, including Australia, the USA and Canada, are adopting a similar target-based approach to salt reduction.7 To date, significant progress has been made by many food manufacturers and retailers in the UK, with salt content being reduced across the board, including by up to 50% in breakfast cereals, 45% in biscuits, 40% in pastry products, 25% in cakes and pasta sauces and 20% in bread.14 15 Furthermore, it has been reported that less salt is being added at the table by consumers.6 The average salt intake in the UK population is steadily decreasing in parallel, with intakes at 8.1 g/day,16 the lowest known accurate figure for any developed country (ie, measured by 24 h urinary sodium excretion),7 but continues to exceed the maximum recommended limit of 6 g/day. However, this represents a 15% reduction from 2001 (9.5 g).17 This reduction in salt intake is accompanied by a fall in the average population blood pressure and a reduction in mortality from stroke and ischaemic heart disease.18 This is estimated to be saving ≈9000 lives every year and resulting in major cost savings to the UK economy of more than £1.5 billion per year.19

Approximately 75% of the salt consumed in the UK and other developed countries comes from processed foods, and is added by food manufacturers prior to consumer purchase.20 Based on the National Diet and Nutrition Survey, the top 10 contributors of salt intake in the UK are bread; bacon and ham; pasta, rice, pizza and other cereals; vegetables (not raw) and vegetable dishes; chicken and turkey dishes; savoury sauces, pickles, gravies and condiments; cheese; sausages; beef and veal dishes; biscuits, buns, cakes, fruit pies and pastries.21 Cheese is one of the top 10 contributors and is widely consumed. In the UK, cheese production for the 12 months ending April 2013 was 376 350 tonnes,22 with an average person consuming 9 kg of cheese per year.21 Cheese is an important contributor of salt intake. In the UK, milk and milk products are estimated to contribute about 9% of salt intake, with cheeses accounting for 44% of the salt consumption in this category and the percentage has not decreased over the past 10 years.17 21 Cheese also contributes to salt intake in many other countries such as the USA (3.8–11%),23 24 Australia (4–7%)25 26 New Zealand (2.8%)27 and Canada (3.2–5.4%).28 29

Cheese is heavily marketed for its high calcium content, particularly to children,30 but as cheese is high in salt and salt intake is the main factor increasing calcium excretion in the urine,31 this claimed benefit requires more evidence to show the effect of cheese on the net calcium balance. Cheese is also a major contributor to fat and saturated fat intake in the UK diet, 6% and 10%, respectively.21

Very little work has been conducted looking at the salt content of cheese in the UK. This research was carried out to evaluate the salt content listed on the labels of cheese products sold in the UK, report the variability in salt level and assess the salt levels in relation to the Department of Health 2012 salt reduction targets.

Methods

Data collection

Data were collected from product packaging and nutrient information panels. The survey was designed as a comprehensive survey of all cheeses available in a snapshot in time, using one large outlet for each of the seven main retailers in the UK.

For each cheese, the data collected included the company name, product name, pack weight, serving size, sodium/salt per 100 g and sodium/salt per portion. When there were missing figures, they were calculated where possible, for example, the missing sodium or salt values were converted by multiplying by 2.5 (sodium to salt) or dividing by 2.5 (salt to sodium). All data were double checked after entry, and a further 5% of entries were checked against the original source in a random selection of products.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Data were collected from each of the major UK supermarkets (Asda, Marks and Spencer, Morrisons, Sainsbury's, Tesco, The Co-operative and Waitrose) to represent salt levels of cheese in the UK. Data were collected for supermarket own brand and branded cheese products available. However, due to resource restrictions only the data for cheddar and cheddar-style cheese products were collected from Morrisons. Packaged cheese products with salt or sodium information labelled were included. Cheese products with other food components such as biscuits/crackers or ham were excluded, with the exception of cottage cheese, cream cheese and Wensleydale traditionally produced with fruits or vegetables. Also, cheese products that contained two different types of cheese were excluded such as a product of grated mozzarella and cheddar cheese and torta con gorgonzola which is a blend of mascarpone and layered gorgonzola cheese. When two sizes were available, the standard weight was used. Cheese types with a sample size less than eight products with nutrient information on the packaging, found across the different supermarkets, were excluded: jarlsberg (4 products), mascarpone (5), Lancashire (2), Leerdammer (4), Maasdam (2), sheep, Appenzeller (1), Bavarian smoked (1) and ricotta (2).

Product categories

Products were categorised into the following types of cheese: brie, Camembert, cheddar and cheddar style, Cheshire, cottage cheese (plain and with pineapple, chilli, pepper, onion and chives), cream cheese (plain and with garlic, herbs, chilli, onion and chives), double Gloucester, edam, emmental, feta, goat's cheese, blue cheese (produced in the UK), other blue cheese (not produced in the UK), gouda, gruyere, halloumi, mozzarella, parmesan (grana padano, parmigiano reggiano and perorino romano), red Leicester, Wensleydale (plain and with fruits), spread and other processed cheese (included singles and string cheeses). This was partially based on the criteria set by the UK Department of Health for cheese salt reduction targets. Data were also categorised separately into supermarket own brand and branded products and hard pressed with and without salt reduction targets and blue cheese with and without salt targets. The hard-pressed cheese category included the following cheese types: emmental, Wensleydale, Cheshire, hard mozzarella, gruyere, red Leicester, double Gloucester, cheddar/cheddar style, parmesan, gouda, edam and halloumi. The blue cheese category included blue cheese produced in the UK and imported into the UK.

Statistical analysis

Comparison among products

Independent samples t test was used to compare the levels of salt between supermarket own brand and branded products, and hard pressed with and without salt reduction targets and blue cheese with and without salt targets and cheddar cheese with and without salt targets.

Data are reported as mean, SD and range as indicated. Significance in all tests carried out was deemed as p<0.05. All data were analysed using SPSS.

Salt targets

For each cheese type, we calculated the total number and percentage of products that met the Department of Health's 2012 salt target for cheese. We used χ2 test to compare the percentage of supermarket own brand and branded products for cheddar and cheddar-style cheese that met the Department of Health's 2012 salt targets.

Results

A total of 612 cheese products met the inclusion criteria and were included in our analysis.

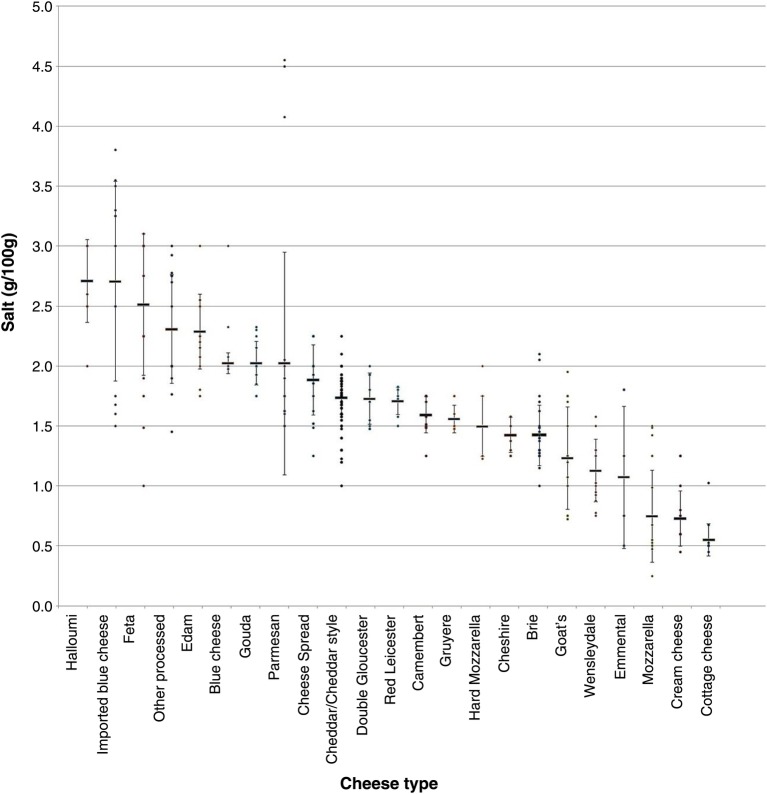

Figure 1 shows the salt level in different types of cheeses per 100 g. Salt content in cheese was high and there was a large variation in salt content between different types of cheeses and within the same type of cheese. On average, eight out of 23 types of cheese contain more than 2 g of salt per 100 g. Halloumi (2.71±0.34 g/100 g) and imported blue cheese (2.71±0.83 g/100 g) contained the highest amounts of salt, whereas only three types of cheeses contained less than 1 g of salt per 100 g; cottage cheese (0.55 g) contained the lowest amount of salt.

Figure 1.

Salt levels (g/100 g) in each type of cheese.

Table 1 compares the salt levels for each type of cheese between supermarket and branded products. Ten of the 23 types of cheeses had a large enough sample size to analyse further; of these, six showed a higher salt level in branded than supermarket own brand products and four showed that supermarket own brand products had a higher salt level.

Table 1.

Salt levels (g/100 g) for each type of cheese between supermarket and branded products

| Cheese type | Supermarket |

Branded |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean±SD | N | Mean±SD | |

| Camembert | 12 | 1.63±0.16 | 4 | 1.49±0.01 |

| Cheddar/cheddar style | 187 | 1.72±0.14 | 63 | 1.78±0.13 |

| Other processed | 14 | 2.48±0.38 | 8 | 2.01±0.44 |

| Cheese spread | 7 | 1.89±0.28 | 12 | 1.88±0.31 |

| Cream cheese | 14 | 0.68±0.24 | 5 | 0.86±0.13 |

| Edam | 12 | 2.38±0.28 | 4 | 2.01±0.28 |

| Emmental | 5 | 0.60±0.14 | 4 | 1.66±0.28 |

| Feta | 18 | 2.51±0.58 | 4 | 2.52±0.71 |

| Goat’s cheese | 16 | 1.23±0.40 | 4 | 1.24±0.58 |

| Mozzarella | 18 | 0.65±0.33 | 4 | 1.16±0.35 |

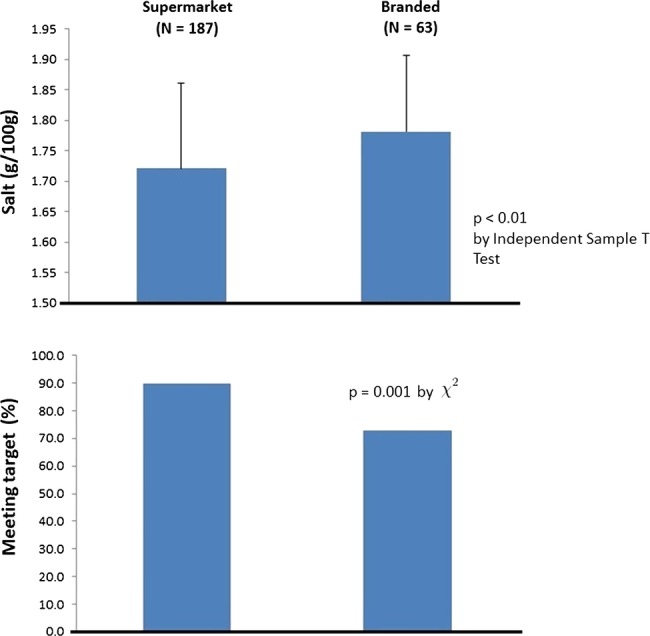

Cheddar and cheddar-style cheese is the major type of cheese in the UK and has the highest number of products in our analysis. The salt level in branded cheddar and cheddar style was 3.5% higher than supermarket own brand (p<0.01; figure 2).

Figure 2.

Salt levels (mean±SD) and percentage meeting salt targets in supermarket and branded cheddar and cheddar-style cheese.

Comparing with the 2012 targets

Among the 23 types of cheese, 10 types had salt targets and 13 did not have targets. Overall, cheeses with targets had significantly lower levels of salt compared with those without targets (table 2). Hard-pressed cheese and blue cheeses with targets also had significantly lower levels of salt compared with those without targets (table 2).

Table 2.

Salt levels in cheese with and without salt targets (g/100 g)

| Cheese type | With target |

Without target |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean±SD | N | Mean±SD | ||

| All | 394 | 1.66±0.42 | 218 | 1.78±0.79 | 0.04 |

| Hard pressed | 303 | 1.70±0.20 | 99 | 1.96±0.72 | 0.00 |

| Blue cheese* | 15 | 2.02±0.09 | 13 | 2.71±0.83 | 0.01 |

*The blue cheese category here included blue cheese produced in the UK and imported into the UK.

Table 3 shows the cheese products meeting the Department of Health 2012 salt targets. Within each cheese category, the average salt level was lower in products that met the targets compared with products that did not meet the target. Overall, among the 394 cheeses that had salt reduction targets, 84.5% have already met their respective 2012 targets. There are three cheese types where all of the products surveyed have met the 2012 targets (table 3) and a larger proportion of cheese types are close to meeting the 2012 targets. However, only double Gloucester (60%) and other processed cheeses, including singles and strings (54.5%), had the lowest proportion of products meeting the targets.

Table 3.

Cheese products meeting the Department of Health 2012 salt targets

| Cheese type | 2012 salt target (g/100 g) | Number of products | Meeting target |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Per cent | Mean±SD (g/100 g) | |||

| Cheddar/cheddar style | 1.8 | 250 | 214 | 85.6 | 1.71±0.12 |

| Other processed | 2 | 22 | 12 | 54.5 | 1.93±0.17 |

| Cheese spread | 2.25 | 19 | 19 | 100 | 1.88±0.29 |

| Cheshire | 1.8 | 8 | 8 | 100 | 1.43 na |

| Cottage cheese | 0.63 | 16 | 14 | 87.5 | 0.51±0.03 |

| Cream cheese | 0.75 | 19 | 14 | 73.7 | 0.61±0.07 |

| Double Gloucester | 1.8 | 10 | 6 | 60.0 | 1.58±0.14 |

| Red Leicester | 1.80 | 21 | 18 | 85.7 | 1.69±0.11 |

| Blue cheese | 2.10 | 15 | 14 | 93.3 | 2.00±0.02 |

| Wensleydale | 1.80 | 14 | 14 | 100 | 1.13 na |

| Overall | na | 394 | 333 | 84.5 | 1.61±0.38 |

na, not applicable.

Table 4 compares the supermarket and branded products that met the 2012 targets. A greater number of supermarket own brand products (90%) compared with branded products (73%) met the target for cheddar and cheddar-style cheese (figure 2).

Table 4.

Percentage of supermarket and branded products that meet the 2012 targets

| Cheese type | 2012 salt target (g/100 g) | Meeting target |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Supermarket (%) | N | Branded (%) | ||

| Cheddar/cheddar style | 1.8 | 168 | 90 | 46 | 73 |

| Other processed | 2.0 | 5 | 36 | 7 | 88 |

| Cheese spread | 2.25 | 7 | 100 | 12 | 100 |

| Cheshire | 1.8 | 8 | 100 | 0 | na |

| Cottage cheese | 0.63 | 14 | 93 | 0 | na |

| Cream cheese | 0.75 | 12 | 86 | 2 | 40 |

| Double Gloucester | 1.8 | 6 | 100 | 0 | na |

| Red Leicester | 1.8 | 17 | 85 | 1 | 100 |

| Blue cheese | 2.1 | 12 | 92 | 2 | 100 |

| Wensleydale | 1.8 | 13 | 100 | 1 | 100 |

Discussion

Salt content in cheeses was found to be high and there was a large variation in salt content between different types of cheeses and within the same type of cheese. In most types of cheese, branded cheese had a higher salt level compared with supermarket own brand. Overall, among the 394 cheeses that had salt reduction targets, 84.5% have already met their respective 2012 targets. Furthermore, 90% of supermarket own brand products met the target for cheddar and cheddar-style cheese compared with 73% of branded products.

Our finding of a high salt content in cheeses sold in the UK is similar to those observed in the USA,32 33 Australia,34 France,35 Belgium,36 Canada,37 New Zealand,38 South Africa39 and Brazil40 showing that high levels of salt in cheese is a global challenge.

Salt has been claimed to be important in the flavour, texture, structure, acceptability, shelf life and safety of cheese,41–43 but the development of cheese with lower salt content has been thriving.44–50 Studies describing the reduction of salt in cheddar cheese are limited, despite the importance of this cheese in the British diet. Those studies that exist involve reducing salt in cheddar cheese51 or the addition of other compounds that can function in ways similar to salt (sodium chloride), such as potassium chloride,44 52–56 magnesium chloride and calcium chloride.57 58

Supermarket own brand cheese have been produced with lower levels of salt, which demonstrates that—despite claims to the contrary—delivering salt reduction appears not to be a technical issue related to cheese manufacture. Corporate decisions about food composition are often based on factors such as common practice, taste and price, rather than health. However, evidence suggests that where salt reductions are made gradually in products, no change in consumer preference is reported.59 60

Our paper, using the example of one of the top 10 contributors of salt to the UK diet—cheese, demonstrates that a national target-based approach to reformulation can be a successful method for reducing the salt content in food. Our findings show that cheese types with salt targets contained less salt than cheese types without salt targets, which suggests that the targets have helped focus and drive the manufacturers to reduce their salt levels. There were three cheese types where all of the products surveyed met the 2012 targets (table 3) and a large proportion of cheese types are close to meeting the 2012 targets. Therefore, the Department of Health has recently reset the targets to lower levels. However, not all cheese types sold in the UK (see online supplementary appendix 1) have a salt target, unlike in other countries such as the New York City salt reduction targets, where they have included a target for parmesan type of cheese.61 Also, some of UK cheese salt targets are less ambitious when compared with New York City salt reduction targets, particularly the main target in this food category, which is for hard-pressed cheeses such as cheddar cheese. In the UK the target is 1.8 g/100 g but in New York it is 1.58 g/100 g for 2012 and 1.5 g/100 g for 2014. Furthermore, the sales-weighted mean (1.67 g) is lower than the average found in our study and lower than the UK 2012 salt target. There is a bigger variation in the cheese types without targets (18–500%); setting a target would narrow this variability.

Limitations

Our study was based on salt content data provided on cheese packaging labels in stores; hence we relied on the accuracy of the data provided on the label. Therefore, it is assumed that the manufacturers provide accurate and up-to-date information in line with European Union regulations. However, further study should include salt content determined through laboratory analysis to achieve a better understanding of the true salt content. When collecting data we did not capture the ingredients list; this means we are unable to ascertain whether salt has been replaced with any other ingredients/additives in the cheese that came out lowest. Such data should be collected in future surveys. Additionally, the salt content in cheese is likely to differ across countries; our data are primarily relevant to the UK. Nevertheless, the results of this study are relevant and serve to document the salt content in cheese products sold in UK supermarkets, providing a foundation for future studies and providing information for programmes and the dairy industry to potentially move towards the reformulation of these products.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates that salt content in cheese in the UK is high and there is a wide variation in the salt content in different types of cheeses and even within the same type of cheese. Despite this, 84.5% of cheeses have already met their respective 2012 targets. These findings demonstrate that much larger reductions in the amount of salt added to cheese could be made and much more challenging targets need to be set.

Other countries around the world now need to follow suit and develop a target-based approach to reducing salt content of processed foods. While the food category emphasis may differ between countries, the concept of using salt targets to achieve a ‘level playing field’ in the industry is universal. A product like cheese is widely consumed internationally and this research demonstrates the variability in salt levels within each type and how targets can help to lower the levels of salt.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GAMG and KHJ conceived the idea and designed the research. KMH conducted the research. KMH and FJH analysed the data. KMH wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and revision of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript. GAMG is the guarantor.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: KMH and KHJ are employees of Consensus Action on Salt & Health (CASH), a non-profit charitable organisation. FJH is a member of CASH and its international branch World Action on Salt & Health (WASH) and does not receive any financial support from CASH or WASH. GAMG is Chairman of Blood Pressure UK (BPUK), Chairman of CASH and Chairman of WASH. BPUK, CASH and WASH are non-profit charitable organisations. GAMG does not receive any financial support from any of these organisations.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The survey showing the salt content of all the products (with their name and brand) is available on request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1.He FJ, MacGregor GA. Reducing population salt intake worldwide: from evidence to implementation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2010;52:363–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He FJ, MacGregor GA. Salt reduction lowers cardiovascular risk: meta-analysis of outcome trials. Lancet 2011;378:380–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Elia L, Rossi G, Ippolito R, et al. Habitual salt intake and risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Clin Nutr 2012;31:489–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devine A, Criddle RA, Dick IM, et al. A longitudinal study of the effect of sodium and calcium intakes on regional bone density in postmenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr 1995;62:740–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He FJ, Marrero NM, MacGregor GA. Salt intake is related to soft drink consumption in children and adolescents: a link to obesity? Hypertension 2008;51:629–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asaria P, Chisholm D, Mathers C, et al. Chronic disease prevention: health effects and financial costs of strategies to reduce salt intake and control tobacco use. Lancet 2007;370:2044–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webster JL, Dunford EK, Hawkes C, et al. Salt reduction initiatives around the world. J Hypertens 2011;29:1043–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet 2011;377:1438–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sixty-Sixth World Health Assembly. Follow-up to the Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA66/A66_R10-en.pdf (accessed 26 Sep 2013)

- 10.Winkler JT. Obesity expose offers slim pickings. BMJ 2012;345:e4465 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salt reduction targets: March 2006. London, UK: Food Standards Agency, 2006. http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/salttargetsapril06.pdf (accessed 29 Jul 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Food Standards Agency. Agency publishes 2012 salt reduction targets. 2009. http://www.food.gov.uk/news/newsarchive/2009/may/salttargets (accessed 29 Jul 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 13. Department of Health Responsibility Deal, 27 July 2012. https://responsibilitydeal.dh.gov.uk/pledges/pledge/?pl=9 (accessed 29 Jul 2013)

- 14.He FJ, Brinsden HC, Macgregor GA. Salt reduction in the United Kingdom: a successful experiment in public health. J Hum Hypertens 2014;28:345–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brinsden HC, He FJ, Jenner KH, et al. Surveys of the salt content in UK bread: progress made and further reductions possible. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health: Assessment of dietary sodium levels among adults (aged 19-64) in England, 2011. http://transparency.dh.gov.uk/2012/06/21/sodium-levels-among-adults/ (accessed 29 Jul 2013)

- 17.Henderson L IK, Gregory J, Bates CJ, et al. National diet & nutrition survey: adults aged 19 to 64. London: TSO, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 18.He FJ, Pombo-Rodrigues S, Macgregor GA. Salt reduction in England from 2003 to 2011: its relationship to blood pressure, stroke and ischaemic heart disease mortality. BMJ Open 2014;4:e004549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Guidance on the prevention of cardiovascular disease at the population level. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/PH25 (accessed 26 Sep 2013)

- 20.James WP, Ralph A, Sanchez-Castillo CP. The dominance of salt in manufactured food in the sodium intake of affluent societies. Lancet 1987;1:426–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Diet and Nutrition Survey: headline results from years 1 and 2 (combined) of the rolling programme 2008/9–2009/10. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216485/dh_128556.pdf (accessed 11 Nov 2013)

- 22.DairyCo. http://www.dairyco.org.uk/market-information/processing-trade/dairy-product-production/uk-dairy-product-production/

- 23. Sodium intake among adults—United States, 2005-2006. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5924a4.htm?s_cid=mm5924a4_e%0D%0A. [PubMed]

- 24.CDC. Centers for disease control and prevention: vital signs: food categories contributing the most to sodium consumption—United States, 2007–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:92–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grimes CA, Campbell KJ, Riddell LJ, et al. Sources of sodium in Australian children's diets and the effect of the application of sodium targets to food products to reduce sodium intake. Br J Nutr 2011;105:468–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlton K, Yeatman H, Houweling F, et al. Urinary sodium excretion, dietary sources of sodium intake and knowledge and practices around salt use in a group of healthy Australian women. Aust N Z J Public Health 2010;34:356–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ministry of Health and the University of Auckland. Nutrition and the burden of disease: New Zealand 1997–2011. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2003. http://www.moh.govt.nz/notebook/nbbooks.nsf/0/A8D85BC5BAD17610CC256D970072A0AA/$file/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garriguet D. Sodium concumption at all ages. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-003-x/2006004/article/sodium/4148995-eng.htm.

- 29.Fischer PWF, Vigneault M, Huang R, et al. Sodium food sources in the Canadian diet. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2009;34:884–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aktas Arnas Y. The effects of television food advertisement on children's food purchasing requests. Pediatr Int 2006;48:138–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cappuccio FP, Kalaitzidis R, Duneclift S, et al. Unravelling the links between calcium excretion, salt intake, hypertension, kidney stones and bone metabolism. J Nephrol 2000;13:169–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agarwal S, McCoy D, Graves W, et al. Sodium content in retail cheddar, mozzarella, and process cheeses varies considerably in the United States. J Dairy Sci 2011;94:1605–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moshfegh AJ, Holden JM, Cogswell ME, et al. Vital signs: food categories contributing the most to sodium consumption—United States, 2007-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:92–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grimes CA, Nowson CA, Lawrence M. An evaluation of the reported sodium content of Australian food products. Int J Food Sci Technol 2008;43:2219–29 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chekri R, Noel L, Millour S, et al. Calcium, magnesium, sodium and potassium levels in foodstuffs from the second French Total Diet Study. J Food Compos Anal 2012;25:97–107 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huybrechts I, De Keyzer W, Lin Y, et al. Food sources and correlates of sodium and potassium intakes in Flemish pre-school children. Public Health Nutr 2012;15:1039–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tanase CM, Griffin P, Koski KG, et al. Sodium and potassium in composite food samples from the Canadian Total Diet Study. J Food Compos Anal 2011;24:237–43 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomson BM, Vannoort RW, Haslemore RM. Dietary exposure and trends of exposure to nutrient elements iodine, iron, selenium and sodium from the 2003-4 New Zealand Total Diet Survey. Br J Nutr 2008;99:614–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Charlton KE, Steyn K, Levitt NS, et al. Diet and blood pressure in South Africa: intake of foods containing sodium, potassium, calcium, and magnesium in three ethnic groups. Nutrition 2005;21:39–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Felicio TL, Esmerino EA, Cruz AG, et al. Cheese. What is its contribution to the sodium intake of Brazilians? Appetite 2013;66:84–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pastorino AJ, Hansen CL, McMahon DJ. Effect of salt on structure-function relationships of cheese. J Dairy Sci 2003;86:60–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ilhak OI, Oksuztepe G, Calicioglu M, et al. Effect of acid adaptation and different salt Ccncentrations on survival of Listeria monocytogenes in Turkish white cheese. J Food Qual 2011;34:379–85 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shrestha S, Grieder JA, McMahon DJ, et al. Survival of Salmonella serovars introduced as a post-aging contaminant during storage of low-salt cheddar cheese at 4, 10, and 21°C. J Food Sci 2011;76:M616–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grummer J, Bobowski N, Karalus M, et al. Use of potassium chloride and flavor enhancers in low sodium cheddar cheese. J Dairy Sci 2013;96:1401–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayyash MM, Sherkat F, Shah NP. Effect of partial NaCl substitution with KCl on the texture profile, microstructure, and sensory properties of low-moisture mozzarella cheese. J Dairy Res 2013;80:7–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karimi R, Mortazavian AM, Karami M. Incorporation of Lactobacillus casei in Iranian ultrafiltered feta cheese made by partial replacement of NaCl with KCl. J Dairy Sci 2012;95:4209–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayyash MM, Shah NP. The effect of substitution of NaCl with KCl on chemical composition and functional properties of low-moisture mozzarella cheese. J Dairy Sci 2011;94:3761–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ayyash MM, Shah NP. Effect of partial substitution of NaCl with KCl on proteolysis of halloumi cheese. J Food Sci 2011;76:C31–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gomes AP, Cruz AG, Cadena RS, et al. Manufacture of low-sodium minas fresh cheese: effect of the partial replacement of sodium chloride with potassium chloride. J Dairy Sci 2011;94: 2701–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Dender AGF, Spadoti LM, Zacarchenco PB, et al. Optimisation of the manufacturing of processed cheese without added fat and reduced sodium. Aust J Dairy Technol 2010;65:217–21 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rulikowska A, Kilcawley KN, Doolan IA, et al. The impact of reduced sodium chloride content on cheddar cheese quality. Int Dairy J 2013;28:45–55 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hystead E, Diez-Gonzalez F, Schoenfuss TC. The effect of sodium reduction with and without potassium chloride on the survival of Listeria monocytogenes in cheddar cheese. J Dairy Sci 2013;96:6172.– [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu Y. Effects of sodium chloride salting and substitution with potassium chloride on whey expulsion of cheese [all graduate theses and dissertations]. Paper 1285, 2012. http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/1285

- 54.Lindsay RC, Hargett SM, Bush CS. Effect of sodium-potassium (1:1) chloride and low sodium-chloride concentrations on quality of cheddar cheese. J Dairy Sci 1982;65:360–70 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reddy KA, Marth EH. Microflora of cheddar cheese made with sodium-chloride, potassium-chloride, or mixtures of sodium and potassium-chloride. J Food Prot 1995;58:54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reddy KA, Marth EH. Lactic-acid bacteria in cheddar-cheese made with sodium-chloride, potassium-chloride or mixtures of the 2 salts. J Food Prot 1995;58:62–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grummer J, Karalus M, Zhang K, et al. Manufacture of reduced-sodium cheddar-style cheese with mineral salt replacers. J Dairy Sci 2012;95:2830–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fitzgerald E, Buckley J. Effect of total and partial substitution of sodium-chloride on the quality of cheddar cheese. J Dairy Sci 1985;68:3127–34 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Girgis S, Neal B, Prescott J, et al. A one-quarter reduction in the salt content of bread can be made without detection. Eur J Clin Nutr 2003;57:616–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liem DG, Miremadi F, Keast RS. Reducing sodium in foods: the effect on flavor. Nutrients 2011;3:694–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. National Salt Reduction Initiative packed food categories and targets. http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/cardio/packaged-food-targets.pdf (accessed 28 Aug 2013)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video abstract