Abstract

Objectives

ACE inhibitors (ACEI) are underutilised despite cardiovascular benefits, in part due to concerns of known transient elevations in serum creatinine (SCr) after initiation. Our objectives were to evaluate rates and predictors of ACEI discontinuation after SCr elevation post-ACEI initiation since limited data are available that examine this issue.

Setting

Primary and tertiary Veterans healthcare system in Los Angeles, California, USA

Participants

3039 outpatients initiating an ACEI with a SCr measured within 6 months prior to and approximately 3 months after initiating an ACEI. Patients were divided into three groups (SCr <1.5, 1.5–2 and >2).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Rates and factors associated with ACEI discontinuation subsequent to SCr elevation after ACEI initiation and for patients with baseline SCr >2 mg/dL, the change in SCr associated with chronic use. Predictors were identified using multivariate logistic regression modelling.

Results

At 3 months follow-up, for those with an increase in SCr, the mean increase post-ACEI initiation was 26%, ranging from −0.01 mg/dL to 0.42 mg/dL varying according to a level of baseline renal function. ACEI discontinuation was higher in patients with elevated baseline SCr (19/165, 11.5%) compared with those with SCr <1.5 (135/2497, 5.4%), and those with SCr 1.5–2.0 (28/377, 7.4%). Male patients, and those with heart failure were less likely to discontinue ACEI after an elevation of SCr post-ACEI initiation, while those taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics and β-blockers were more likely to discontinue ACEI.

Conclusions

SCr increases <30% on average within 3 months of ACEI initiation, with subsequent discontinuation rates varying by baseline SCr. Elevation in SCr was not associated with ACEI discontinuation rates. In patients with SCr >2 mg/dL at baseline, despite an acute increase in SCr after ACEI initiation, chronic ACEI use was associated with a decrease in SCr in most patients.

Keywords: INTERNAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To date, no studies have evaluated the acute elevation in serum creatinine post-ACE inhibitor initiation and the predictors of subsequent discontinuation following an elevated serum creatinine.

This study confirmed the mean increase in serum creatinine after ACE inhibitor initiation is 26%, varying with baseline renal function.

Factors other than elevation in serum creatinine were associated with ACE inhibitor discontinuation, including, female sex, absence of heart failure and use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diuretics or β-blockers.

Introduction

Current guidelines recommend ACE inhibitors (ACEIs) as the standard of therapy for postmyocardial infarction, chronic heart failure (CHF) and diabetes due to the substantial endothelial, cardiovascular and renal protection.1–4 Furthermore, ACEIs have also been shown to be a beneficial therapy for hypertension.5 The renal protective mechanism of ACEIs vary, ranging from improving vascular endothelium function to vasodilatation effects.6 Despite evidence from numerous trials showing the benefits of improved morbidity and mortality by ACEIs, these drugs are still underutilised.1–4 7–10 Clinicians are reluctant to start and continue with adequate dosing of ACEIs primarily due to concerns of elevations in serum creatinine (SCr), particularly in patients with chronic kidney disease despite evidence that this group of patients benefits from ACEI.10 11 The most probable cause of an acute elevation in SCr post-ACEI initiation is the decrease in vasoconstriction in the efferent arterioles resulting in pressure reduction in the glomerular apparatus and decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR).6 However, homeostasis of haemodynamics occurs with long-term use with gradual return and improvement in GFR.7 Even with concerns of an acute rise in SCr, ACEIs provide long-term benefits with some data suggesting an improvement in renal function with decrease in SCr with long-term use.7 11 12

In patients with HF, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) estimate that between 2.4% and 16% of patients experience an acute increase in SCr of > 0.5 mg/dL after ACEI initiation, with improvement with chronic use.8 9 In a practice-based setting, Bakris and colleagues demonstrated a mean increase in SCr of 30% in a hypertensive population using ACEIs with the increase stabilising within 2 months after ACEI initiation. This rise in SCr is proportional to the baseline SCr, such that a 30% increase at a SCr of 2 would be 2.6 while at a SCr of 1, it would be only 1.3, it is reversible on discontinuation and it is less likely to occur beyond 4 weeks of initiation.13 14 Patients with HF suffer a more pronounced increase in SCr with ACEIs due to a reduction of blood flow to the kidneys from reduced cardiac output, diuretic use and vasodilation effect. Although the acute increase in SCr seen in patients with HF ranges from 75% to 200% from baseline after ACEI initiation, this elevation was suggested as being acceptable since ACEIs have proven benefits in decreasing mortality in this population.8 15

The frequency of the discontinuation rate of ACEI and the determinant factors associated with discontinuation in the real world setting has not been fully characterised. The CONSENSUS II HF trial reported a discontinuation rate of 4.6% with enalapril subsequent to the rise of SCr, while a meta-analysis of RCTs of patients with HF found an ACEI discontinuation rate of 13.8%, of which only 0.4% was attributed to an increase in SCr.7 16

To date, no studies have evaluated the acute elevation in SCr post-ACEI initiation and the predictors of subsequent discontinuation following an elevated SCr. Assessment of these patterns may provide insight into clinician decision making in a real world setting. The objective of our study was to assess the rates and predictors of ACEI discontinuation following an increase in SCr post-ACEI initiation, each according to baseline renal function.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective observational cohort study of all outpatients initiating an ACEI between 2002 and 2004 at the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System (VAGLAHS). The Veterans Health Information System and Technology Architecture (VISTA) database was used to gather patient information (demographics, medication use, allergies, comorbidities and laboratory results).

Initiation of ACEI was defined as the dispensing of an outpatient prescription for an ACEI with no previous record of ACEI use in the past 6 months. The following ACEI information was collected: initiation date, discontinuation date, adverse drug reactions (ADR), dosage, dosing frequency and the total daily dose. To determine the prevalence of a change in SCr, SCr was recorded at baseline (within 6 months of ACEI initiation) and 3 months (10–14 weeks) post-initiation. If SCr data were not available between 10 and 14 weeks (3 months), the data value of the most proximal assay was recorded. A 0.5 mg/dL increase and 30% increase in SCr was considered to be clinically important since several studies have used this as a reference point to define a decrease in renal function.5 6 14 Discontinuation of ACEI was defined as no refills within 90 days after the last filled prescription which allowed a lenient grace period for patients obtaining late refills. Patients were stratified into three baseline SCr groups (group 1: SCr <1.5 mg/dL; group 2: 1.6–2.0 mg/dL; and group 3: >2.0 mg/dL) for analysis. We assessed above and below 0.5 mg/dL and 30% to determine the threshold at which discontinuation occurred and to analyse possible differences in threshold by group. For those patients with a baseline SCr >2 mg/dL and continued on an ACEI, SCr was recorded at 1 year to detect any changes post-initiation. Comorbidities (defined by International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes: 425-cardiomyopathy, 428-congestive HF, 250-diabetes, 410–414-coronary artery disease, 274-gout, 401-hypertension) and concurrent use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), diuretics and β-blockers were documented to determine potential factors associated with an increase in SCr and the discontinuation of ACEIs. Concomitant medication use was defined as having an active prescription within 1 month of the index date of ACEI prescription through the time of discontinuation.

The end points of this study were: the proportion of patients with a significant increase in SCr post-ACEI initiation at 3 months follow-up defined as >0.5 mg/dL or >30% of baseline by group; the proportion of patients with ACEI discontinued following a rise in SCr by group; the threshold of increase in SCr associated with ACEI discontinuation, stratified by baseline SCr groups; factors (patient characteristics, comorbidities and concurrent medications) that may be associated with discontinuation of ACEIs; and the change in SCr in patients with baseline SCr >2 mg/dL and continued on ACEIs for 1 year.

Continuous baseline characteristics were expressed as the mean±SD or median; and categorical baseline characteristics were expressed as a proportion. χ2 Test was used to compare the discontinuation rate after detecting a rise in SCr post-ACEI use between groups and to compare the threshold of increase in SCr prior to discontinuation between groups. A multiple logistic regression model was constructed to identify the factors associated with SCr elevation subsequent to ACEI initiation and ACEI discontinuation. The univariate model included patient characteristics (ie, age and gender), comorbidities (ie, diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, CHF, systolic blood pressure (SBP) <100 mm Hg and gout), concomitant NSAID use, diuretic use (ie, thiazide, loop, K+ sparing), β-blocker use and significant SCr elevation defined as >0.5 mg/dL or >30% of baseline. Variables with p<0.2 from the univariate model were placed in a multiple logistic regression model using stepwise selection. OR with 95% CI were estimated from the regression model. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All results were analysed using SAS (V.8.2, SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

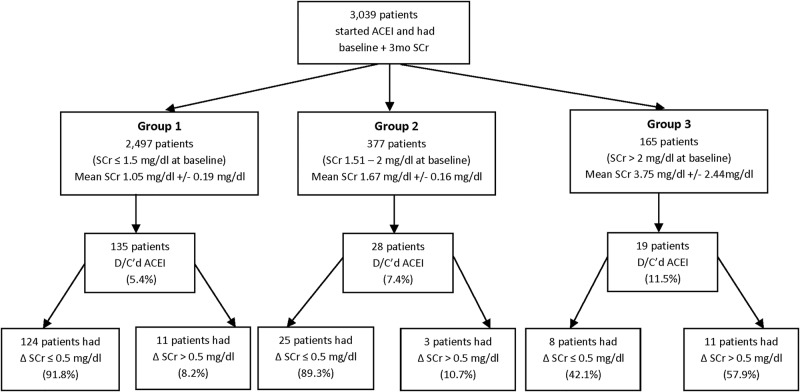

A total of 3039 patients were initiated on an ACEI between January 2002 and December 2004 and had a SCr measured within 6 months prior to and 3 months after initiating an ACEI (figure 1). The average age was 65 years and 97.6% were men with a baseline SCr of 1.28±0.86 mg/dL. Patients were stratified into three groups based on baseline SCr: group 1 consisted of 2497 patients with a SCr of <1.5 mg/dL (mean of 1.05±0.19); group 2 had 377 patients with a SCr of 1.5–2 mg/dL (mean of 1.67±0.16); and group 3 had 165 patients with a SCr of >2.0 mg/dL (mean of 3.75±2.44; figure 1). Hypertension (44.2%) and diabetes (28.5%) were the most frequently documented comorbidities and the most common concomitant medications were diuretics and β-blockers (table 1).

Figure 1.

Profile of patients included in the analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of cohort (n=3039)

| Characteristic | Value* |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean±SD, median) | 65±12, 65 | |

| Gender (n, %) | ||

| Male | 2966 | 97.6% |

| Ethnicity (n, %) | ||

| African-American | 414 | 13.6% |

| Caucasian | 670 | 22.0% |

| Hispanic | 44 | 1.45% |

| Other | 341 | 11.2% |

| Not documented | 1570 | 51.7% |

| Baseline serum creatinine (mg/dL, mean±SD, median) | Mean±SD, Median | |

| Overall (n=3039) | Overall: Overall: 1.28±0.86, 1.10 | |

| Group 1: <1.5 mg/dL (n=2497) | Group 1: <1.5 mg/dL=1.05±0.19, 1.03 | |

| Group 2: 1.5–2.0 mg/dL (n=377) | Group 2:1.5–2.0 mg/dL=1.67±0.16, 1.6 | |

| Group 3: >2 mg/dL (n=165) | Group 3: >2 mg/dL=3.75±2.44, 2.7 | |

| n | Per cent | |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 866 | 28.5 |

| Hypertension | 1343 | 44.2 |

| Chronic heart failure | 177 | 5.8 |

| Coronary artery disease | 445 | 14.6 |

| Gout | 69 | 2.3 |

| SBP <100 mm Hg | 88 | 2.9 |

| Concomitant use of: | ||

| NSAIDs | 1053 | 34.6 |

| Diuretics (total) | 1771 | 58.3 |

| Loops | 773 | 25.4 |

| Thiazides | 1264 | 41.6 |

| K-sparing | 239 | 7.9 |

| β-blockers | 1601 | 52.7 |

*Values are reported as mean±SD; median unless otherwise noted.

NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SBH, systolic blood pressure.

On average, patients had a follow-up SCr available at a median of 3.8 months post-ACEI initiation. The mean changes in SCr at 3 months follow-up most proximal to the 3-month interval were 0.05±0.30 mg/dL, −0.01±0.31 mg/dL and 0.42−2.20 mg/dL, respectively, by group (p>0.05 vs baseline for all groups). There was no change in median SCr at 3 months follow-up for all three groups. Counting only those patients with an increase in SCr for all three groups, based on an increase from baseline SCr (n=182), the average per cent increase in SCr prior to ACEI discontinuation was 25.98%±41.72 with a median of 13.49%.

At 3 months, the discontinuation rate of ACEI with or without concomitant SCr rise of >0.5 mg/dL was highest in group 3 (11.5%), followed by group 2 (7.4%) and group 1 (5.4%; p<0.001; figure 1). In the multiple logistic regression models the variables significantly associated with a greater likelihood of ACEI discontinuation were the use of NSAIDs, diuretics and β-blockers (table 2). Of note, a significant increase in SCr (defined as >0.5 mg/dL or >30%) was not associated with ACEI discontinuation. (p=0.498 in the univariate model). A history of CHF, SBP of <100 mm Hg at baseline and male sex were significantly associated with a reduced likelihood of ACEI discontinuation.

Table 2.

Multivariate OR for discontinuation of ACE inhibitors subsequent to elevation of SCr post-ACEI initiation

| Co morbidities | Multivariate OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00)* | 0.452 |

| Gender (male) | 0.74 (0.57 to 0.97) | 0.028 |

| Coronary artery disease | 0.89 (0.79 to 1.01) | 0.061 |

| Chronic heart failure | 0.79 (0.63 to 0.99) | 0.041 |

| SBP <100 mm Hg | 0.55 (0.40 to 0.76) | <0.001 |

| Concomitant use of: | ||

| NSAIDs | 1.23 (1.13 to 1.34) | <0.001 |

| Diuretics | 1.07 (0.87 to 1.31) | <0.001 |

| Thiazides | 1.18 (0.98 to 1.42) | 0.084 |

| Loops | 0.99 (0.84 to 1.18) | 0.925 |

| β-blockers | 1.17 (1.08 to 1.27) | <0.001 |

*Values rounded from 0.999 (0.995 to 1.002).

NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SBH, systolic blood pressure.

Changes in SCr were further evaluated based on absolute and per cent change. Table 3 depicts the change in SCr prior to ACEI discontinuation, at the threshold of 0.5 mg/dL and 30% increase in SCr (in 182 patients (5.9%) of all patients initiated on ACEI who had an increase in SCr). Group 3 had the highest mean increase in SCr as absolute and per cent change. A majority of the patients who experienced an increase in SCr had a change less than 30% increase and 0.5 mg/dL increase prior to discontinuation. Thus, most ACEI discontinuation did not occur following a clinically significant increase in SCr (>30% or >0.5 mg/dL above baseline).

Table 3.

Distribution in magnitude of elevation of serum creatinine in patients who discontinued ACE inhibitors within 90 days post-initiation

| Threshold of increase in SCr | Group 1* <1.5 mg/dL n=135 |

Group 2* 1.5–2 mg/dL n=28 |

Group 3* >2 mg/dL n=19 |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤0.5 mg/dL increase | 124 (91.85) 0.17±0.11; 0.10 |

25 (89.29) 0.18±0.8; 0.17 |

8 (42.10) 0.27±0.14; 0.3 |

<0.001 |

| >0.5 mg/dL increase | 11 (8.15) 1.23±0.99; 0.80 |

3 (10.71) 0.87±0.25; 0.9 |

11 (57.90) 2.95±2.93; 1.7 |

<0.001 |

| ≤30% increase | 114 (84.45) 14.15%±6.85%; 11.11% |

25 (89.29) 10.22%±4.6%; 9.25% |

12 (63.15) 12.82%±6.64%; 12.99% |

0.01 |

| >30% increase | 21 (15.55) 89.25%±81.07%; 46.67% |

3 (10.71) 45.83%±8.78%; 45% |

7 (36.85) 100.32%±69.10%; 88.23% |

<0.001 |

*Values are n (%) and mean±SD; median.

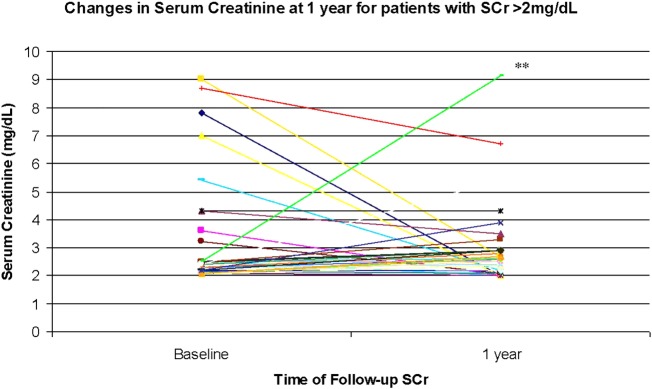

Of the 165 patients with a baseline SCr >2.0 mg/dL (mean 3.75±2.44), only 50 patients (30.3%) were continued on an ACEI at 1 year. A total of 69 of the 165 (41.8%) patients experienced a decrease in SCr prior to discontinuation (average decrease was 1.04±1.77) and 76 (46.0%) of the patients experienced an increase (average increase was 1.86±0.87) and 20 (12.1%) patients experienced no change from baseline prior to discontinuation. Of the 50 patients who continued on ACEIs, only 35 patients had a follow-up in SCr at 1 year and their mean decrease in SCr was −0.24±0.56 with a median decrease of −0.01 mg/dL. Of these 35 patients, 1 (2.86%) had a larger increase in SCr (from 2.5 to 9.1 mg/dL) as compared with the remaining patients in the group (figure 2). Excluding this participant as an outlier with a rise in SCr at 1 year that is unlikely due to ACEI, resulted in a mean decrease in SCr at 1 year in group 3 of −0.44±1.96 with a median of 0.01 mg/dL. While the majority (54.28%) of patients in group 3 experienced a clinically significant absolute (>0.5 mg/dL) increase in SCr of 0.98±1.58 compared with a baseline of 3.75±2.44, the 27% relative increase was not above the generally accepted threshold of >30%. Forty per cent of this group experienced a decrease in SCr of 1.19±2.26 compared to baseline 3.75±2.44 and 5.7% had no change in SCr at 1-year follow-up. The average magnitude of decrease in SCr was greater than the average magnitude of increase in SCr with long term use of ACEI (1.19±2.26 mg/dL decrease vs 0.98±1.58 mg/dL increase, p<0.001) in patients with SCr >2 mg/dL.

Figure 2.

Change in serum creatinine at 1 year for patients with serum creatinine (SCr) >2 mg/dL. x-Axis: time of follow-up SCr; y-axis: SCr (g/dL). *The mean change in serum creatinine was −0.24±0.56 mg/L with a median of −0.01 mg/dL. Excluding outlier (**) resulted in a mean in change serum creatinine of −0.44±1.96 mg/dL with a median of −0.01 mg/dL N=35.

Discussion

In our study, which had a large hypertensive population, we showed an increase in SCr of approximately 26% post-ACEI initiation, for those with an increase in SCr. Previous studies have documented similar acute increases in SCr of 30% in hypertensive patients and up to 200% in patients with HF.13 14 It has been suggested that ACEI discontinuation be considered if an increase in SCr exceeds 30% with ACEI use since renal function may be compromised beyond this increase and the benefits of ACEI may not outweigh the risks.13 Our study showed that the majority of ACEI discontinuation occurred with an increase of less than 30% in SCr, thus suggesting that the threshold of concern for renal deterioration is lower in clinical practice or other factors may be more likely associated with discontinuation.

According to previous trials, a change in SCr of >0.5 mg/dL may also be considered clinically significant.8 9 The majority of the patients that discontinued ACEI in our study experienced a <0.5 mg/dL change in SCr. Our study further suggested that on average, SCr was not greatly affected by ACEI since all three groups had no change in median SCr over 3 months. Thus, the discontinuation of ACEI in our population was most likely attributed to drug intolerances, such as, cough, other comorbidities, and concomitant medications, rather than the change in SCr. Only 6% of patients in the lower baseline SCr group suffered from documented cough or nausea leading to the discontinuation of ACEI. The adjusted regression analysis demonstrated that concomitant use of NSAIDs, diuretics and β-blockers were factors associated with a higher likelihood of ACEI discontinuation. This may be anticipated since NSAIDs and diuretics have been documented to decrease renal function and exacerbate SCr elevations when used concomitantly with ACEI.12 However, this may have led to the discontinuation of ACEI at a lower threshold of SCr increase. If discontinuation of ACEI was indeed at a lower threshold than that traditionally accepted (SCr rise >0.5 or 30%), improved awareness for clinicians of the short duration of an acute rise in SCr when initiating ACEI and dose reduction or reassessment of need for concomitant NSAIDs or diuretics may be beneficial strategies. This may confer better clinical outcomes for patients, particularly diabetic patients who would benefit from the nephroprotective actions of ACEI. Contrary to previous findings, β-blockers were associated with a higher likelihood of discontinuation with concomitant use of ACEI in our study rather than exerting a renoprotective effect with ACEI use.14 Male sex, CHF history and SBP of <100 mm Hg were also associated with a lower chance of ACEI discontinuation. We postulated that patients with CHF and SBP <100 mm Hg were more likely to be maintained on an ACEI since HF studies have documented benefits of ACEI in decreasing morbidity and mortality.1 7 8

In patients with baseline SCr >2 mg/dL, our study showed that SCr can increase, decrease or remain unchanged with long term ACEI use. Even though the majority of these patients experienced an acute increase in SCr, our results support ACEI use in renal impaired patients since the median change in SCr decreased and in the long term, the magnitude of decrease was much more impressive than the magnitude of increase. Our study is consistent with the prospective findings by Hou et al11 and retrospective findings by Hirsch et al15 who both found that despite the acute increase in SCr, long-term improvement in SCr occurs in many patients with impaired renal function at baseline.16 The use of ACEI is warranted in this group of patients, along with close monitoring of renal function and electrolytes since benefits were documented in this study as well as in previous studies.11 12 17–20

Limitations of our study include its retrospective study design with potential for confounding.21 Given our Virginia population, the vast majority of patients were men, limiting generalisability to female patients. In addition, the electronic medical records may not be complete and accurate as is a limitation of any study relying on retrospective medical chart extraction. We did not have data on the peak creatinine, nor comprehensive assessment of all adverse events given our data extraction methods. Finally, the sample size of patients with SCr >2 mg/dL was small prefollow-up and postfollow-up of SCr, particularly at 1 year follow-up. Exploration of the reasons for ACEI discontinuation long term in this group would be beneficial. However, the large population-based sample increases the generalisability of the findings.

Many clinicians may be reluctant to prescribe ACEIs to all eligible patients due to concerns of an elevation in SCr. Based on this real world study, the magnitude of increase in SCr post-ACEI initiation was slightly lower than the commonly used threshold of 30%. We found that, instead of a clinically meaningful rise in SCr, ACEI discontinuation may be more likely associated with either comorbidities, concomitant medications that may increase SCr, or a low threshold of concern for SCr elevations. Identification of other factors that may increase SCr, such as, NSAID use, diuretic use and volume depletion should be considered before an ACEI is discontinued. The importance of monitoring should be emphasised to detect any drastic increase in SCr >30% and to manage potential ADRs. Education may be required to change practice patterns in patients with impaired baseline renal function to confer the clinical benefit of chronic ACEI nephroprotection.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: CAJ involved in the concept/design, data interpretation, critical revision of article, approval of article, statistics. JW involved in the design, data analysis/interpretation, drafting article, approval of article, statistics. IA involved in the data analysis, critical revision of article, approval of article, statistics. MG involved in the data collection/interpretation, critical revision of article, approval of article. FVM involved in the concept/design, data interpretation, critical revision of article, approval of article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This was a non-funded study approved by the institutional review board at VAGLAHS and Western University of Health Sciences.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hung SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. American College of Cardiology; ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Heart Failure) http://www.acc.org/clinical/guidelines/failure//index.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction-executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:671–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2014. Diabetes Care 2014;37;S5–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marre M, Leblanc H, Suarez L, et al. Converting enzyme inhibition and kidney function in normotensive diabetic patients with persistent microalbuminuria. BMJ 1987;294:1448–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. JAMA 2003;289:2560–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuda H, Hayashi K, Arakawa K, et al. Zonal heterogeneity in action of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor on renal microcirculation. J Am Soc Nephrol 1999;10:2272–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed A, Kiefe C, Allman R, et al. Survival benefits of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in older heart failure patients with perceived contraindications. J Amer Ger Soc 2002;50:1659–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The CONSENSUS Trial Study Group. Effects of enalapril on mortality in severe congestive heart failure: results of the Cooperative North Scandinavian Enalapril Survival Study (CONSENSUS). N Engl J Med 1986;316:1429–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The SOLVD Investigators. Effects of enalapril on mortality and the development of heart failure in asymptomatic patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions. N Engl J Med 1987;325:293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghali JK, Giles T, Gonzales M, et al. Patterns of physician use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in the inpatient treatment of congestive heart failure. J. La State Med Soc 1997;149:474–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hou FF, Zhang X, Zhang GH, et al. Efficacy and safety of benazepril for advanced chronic renal insufficiency. N Engl J Med 2006;354:131–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoolwerth AC, Sica D, Ballerma B, et al. Renal considerations in angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor therapy: a statement of healthcare professional from the Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease and the Council of High Blood Pressure Research of the American Heart Association. Circulation 2001;104:1985–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bakris GL, Weir MR. Angiotensin- converting enzyme inhibitor associated elevations in SCr. Is this a cause for concern? Arch Intern Med 2000;168:685–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knight E, Glynn R, McIntyre K, et al. Predictors of decreased renal function in patients with heart failure during angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy: results from the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD). Am Heart J 1999;138:849–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch S, Hirsch J, Udayan B, et al. Tolerating increases in serum creatining following aggressive treatment of chronic kidney disease, hypertension and proteinuria: pre-renal success. Am J Nephrol 2012;36:430–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G. Dealing with renin-angiotensin inhibitors, don't mind serum creatinine. Am J Nephrol 2012;36:427–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed A. Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with heart failure and renal insufficiency: how concerned should we be by the rise in SCr. J Amer Ger Soc 2002;50:1297–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raebel M, Lyons E, Andrade S, et al. Laboratory monitoring of drugs at initiation of therapy in ambulatory care. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:1120–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA 2003;289:1107–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raebel M, Lyons E, Chester E, et al. Randomized trial to improve safety monitoring of ongoing drug therapy in ambulatory patients. Pharmacotherapy 2006;5:626–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hess D. Retrospective studies and chart reviews. Respir Care Oct 2004;49:1171–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.