Abstract

Objectives

Chromosome 9p21 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is a susceptibility variant for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in the primary prevention setting. However, it is controversial whether this SNP is also associated with recurrent myocardial infarction (ReMI) in the secondary prevention setting. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the impact of chromosome 9p21 SNP on ReMI in patients receiving secondary prevention programmes after AMI.

Design

A prospective observational study.

Setting

Osaka Acute Coronary Insufficiency Study (OACIS) in Japan.

Participants

2022 patients from the OACIS database.

Interventions

Genotyping of the 9p21 rs1333049 variant.

Primary outcome measures

ReMI event after survival discharge for 1 year.

Results

A total of 43 ReMI occurred during the 1 year follow-up period. Although the rs1333049 C allele had an increased susceptibility to their first AMI in an additive model when compared with 1373 healthy controls (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.33, p=2.3*10−4), patients with the CC genotype had a lower incidence of ReMI at 1 year after discharge of AMI (log-rank p=0.005). The adjusted HR of the CC genotype as compared with the CG/GG genotypes was 0.20 (0.06 to 0.65, p=0.007). Subgroup analysis demonstrated that the association between the rs1333049 CC genotype and a lower incidence of 1 year ReMI was common to all subgroups.

Conclusions

Homozygous carriers of the rs1333049 C allele on chromosome 9p21 showed a reduced risk of 1 year ReMI in the contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention era, although the C allele had conferred susceptibility to their first AMI.

Keywords: Acute Myocardial Infarction, Secondary Prevention, Single Nucleotide Polymorphism, 9p21

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to clearly show a change of the susceptibility risk of the 9p21 variant to acute myocardial infarction between the primary and secondary prevention settings in a percutaneous coronary intervention era.

Data regarding the mechanism and culprit lesion of remyocardial infarction were not available.

Replication studies with a larger sample are warranted to confirm our observations.

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is one of the leading causes of death and disability worldwide.1 AMI is associated with a positive family history as well as several traditional coronary risk factors including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia and smoking, suggesting that the pathogenesis of AMI has a substantial genetic component.2 Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified several genetic loci that confer susceptibility to AMI and coronary artery disease (CAD) in the primary prevention setting.3–7 Among these genetic variants, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on chromosome 9p21 are the most common and significant susceptibility risk factors for AMI and CAD, regardless of race.3–11 However, it remains controversial whether chromosome 9p21 SNPs are associated with recurrent myocardial infarction (ReMI) in patients with post-AMI receiving the evidence-based secondary prevention programmes.12–14

For example, the Italian Genetic study and TexGen registry revealed that 9p21 genetic variation was not associated with ReMI events after early-onset myocardial infarction and acute coronary syndrome (ACS), respectively,13–14 while the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) genetic study showed that risk allele carriers of 9p21 SNPs had a higher incidence of ReMI after ACS.12 One possible explanation for this discrepancy among these three studies is an involvement of in-hospital ReMI as an end point. It is reported that 9p21 SNPs increase the risk of AMI onset by promoting the development and progression of coronary plaque deposition, rather than increasing susceptibility to plaque rupture.9–14 Thus, inclusion of acute phase ReMI might have made the interpretation difficult in these 9p21 variant studies, as most of the ReMI occurring during the acute phase of AMI were most likely caused by 9p21-independent mechanisms, such as reocclusion of the culprit lesion and/or thrombosis. Therefore, to simply assess the susceptibility impact of 9p21 to ReMI in the secondary prevention settings, it may be better to include patients with post-AMI only who survived the acute stage and received the state-of-the-art secondary prevention programmes after discharge.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the susceptibility impact of 9p21 genetic variation on ReMI in consecutive 2022 patients with a first AMI who were registered in the Osaka Acute Coronary Insufficiency Study (OACIS),15–19 treated with emergent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and discharged alive.

Methods

The OACIS

The OACIS is a multicentre, prospective observational registry for AMI in Japan that was initiated in April 1998 among 25 collaborating hospitals. It is designed to assess patient demographics including genomic information, therapeutic procedures and subsequent clinical events in patients with AMI. All study candidates were informed about data collection, blood sampling and genotyping, and provided written informed consent. Research cardiologists and trained research nurses recorded data using a specific reporting form. The diagnosis of AMI was based on the WHO criteria,20 which required two of the following three criteria to be met: (1) clinical history of central chest pressure, pain or tightness lasting ≥30 min; (2) ST segment elevation >0.1 mV in at least one standard and (3) a rise in serum creatinine phosphokinase concentration to more than twice the normal laboratory value. The OACIS is registered to the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR) in Japan (ID: UMIN000004575). Other details of the OACIS are described elsewhere.15–19

Study design

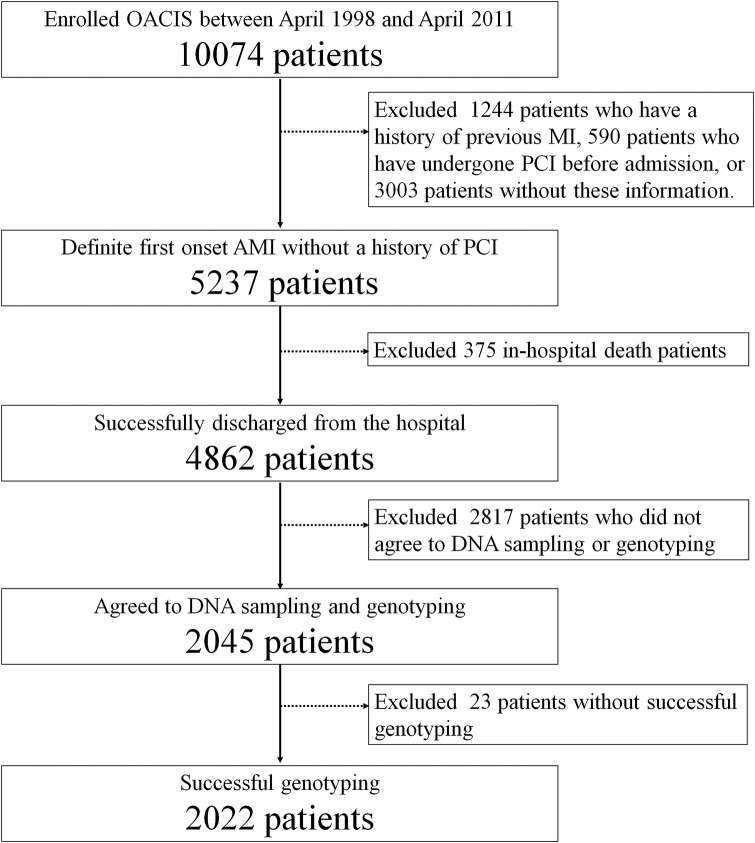

Among 10 074 consecutive patients with AMI registered in the OACIS between April 1998 and April 2011, 2045 patients who had a first AMI, underwent emergent PCI, survived to discharge and gave written informed consent to the study were enrolled in this study. Exclusion criteria included a history of previous myocardial infarction or PCI, in-hospital death cases and lack of written informed consent for genetic study and DNA sampling. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples using a commercially available kit (QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Patients were genotyped for the rs1333049 SNP of chromosome 9p21 using the multiplex-PCR-based invader assay as previously described.21 We focused on the rs1333049 because it is the most widely studied 9p21 genetic variant in the primary and secondary prevention settings.8 10–12 14 We also confirmed that rs1333049 is in linkage disequilibrium with other major 9p21 SNPs in the OACIS registry (see online supplementary figure S1). Finally, the genotyping success rate for rs1333049 was 98.9% and 2022 patients were successfully genotyped and analysed for susceptibility to ReMI within a year after survival discharge (figure 1). To validate the association of the rs1333049 SNP with the first AMI, we performed a case–control association study between the present study population and healthy Japanese controls. Control blood samples of healthy Japanese adults (n=1373, mean age, 38.6 years old, 59% male) were obtained from the Health Science Research Resources Bank (Osaka, Japan). The patient backgrounds and primary preventive medications were not adjusted in this case–control association study in the primary prevention setting, since these data were not available in commercially obtained healthy controls and medications before first AMI were not available in our study population in detail.

Figure 1.

Patient selection flow chart. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; MI, myocardial infarction; OACIS, Osaka Acute Coronary Insufficiency Study; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Statistical analysis

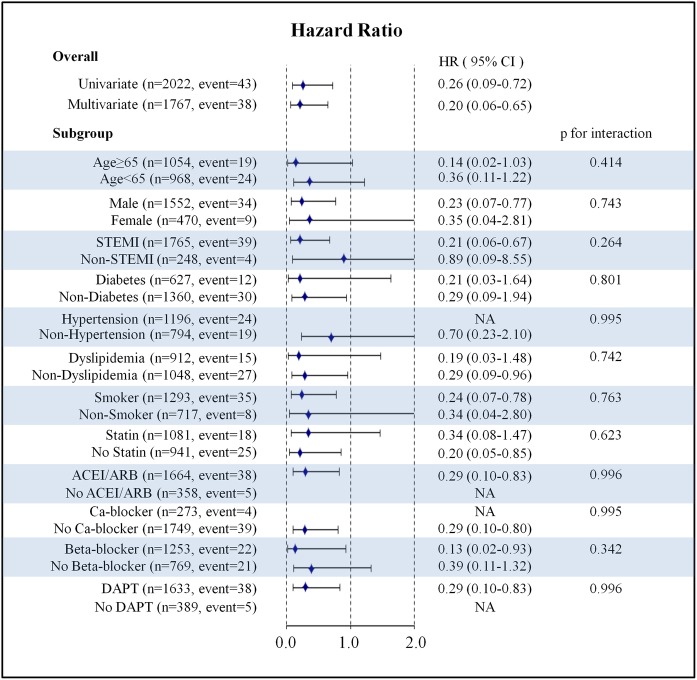

Categorical variables were compared by the χ2 test, and continuous variables were compared by the Kruskal–Wallis test. The impact of the rs1333049 genotype on the onset of AMI was assessed in the primary and secondary prevention settings. The impact of rs1333049 on the onset of AMI was calculated as ORs and 95% CIs in an additive model (OR per C allele increase). In the secondary prevention analysis, the Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate event rates. Since the Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that the incidence of ReMI differed between the CC and CG/GG genotypes of rs1333049 (figure 2), the differences between the CC and CG/GG genotypes were assessed by the log-rank tests. In addition, a Cox regression model was used to compare the 1 year prognostic impacts between the rs1333049 CC and CG/GG genotypes based on the estimated HRs and 95% CI. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to reduce the confounding effects of variations in patient backgrounds using age, gender, body mass index, ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking, target lesion, multivessel disease, peak creatinine phosphokinase and prescription of ACE inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, β-blockers, calcium channel blockers, statins, diuretics and dual antiplatelet agents as covariates. Hence, the final multivariate model included all the aforementioned covariates regardless of the univariate results shown in online supplementary table S1 because we assumed that even non-significant differences in these covariates could be confounders and should be adjusted. Gene–drug interactions were evaluated using p for the interaction between genotype and each drug tested. Statistical significance was set as p<0.05 for comparison of patient background or gene–drug interaction. Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was employed during the secondary prevention analysis and statistical significance was set as p<0.025 (0.05 divided by the number of independent testing; log-rank test and multiple Cox regression analysis). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA) or R software packages V.2.15.1 (R Development Core Team).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of remyocardial infarction event.

Results

Patient characteristics and medications at discharge are shown in table 1. The median age was 65 years, 76.8% were male and 87.7% had ST-elevation myocardial infarction. No significant differences in patient background based on rs1333049 genotypes were detected.

Table 1.

Patient background based on the rs1333049 Genotype

| Parameter | Overall (n=2022) |

CC (n=574) |

CG (n=997) |

GG (n=451) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65 (57–73) | 65 (57–73) | 65 (57–73) | 65 (58–73) | 0.986 |

| Male, % | 76.8 | 78.6 | 75.2 | 77.8 | 0.265 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.8 (21.9–25.9) | 23.9 (21.8–25.7) | 23.7 (21.8–25.8) | 23.8 (22.0–26.0) | 0.653 |

| STEMI, % | 87.7 | 88.1 | 86.6 | 89.6 | 0.272 |

| Coronary risk factor | |||||

| Diabetes, % | 31.6 | 33.0 | 29.7 | 33.7 | 0.227 |

| Hypertension, % | 60.1 | 61.0 | 59.5 | 60.3 | 0.829 |

| Dyslipidemia, % | 46.5 | 43.8 | 47.2 | 48.5 | 0.267 |

| Smoking, % | 64.3 | 63.6 | 64.4 | 65.2 | 0.868 |

| CAG Findings | |||||

| Target lesion | 0.153 | ||||

| Left main trunk, % | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | |

| LAD, % | 45.1 | 43.2 | 43.7 | 50.3 | |

| Diagonal branch, % | 2.9 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 3.1 | |

| RCA, % | 35.8 | 37.3 | 35.6 | 34.4 | |

| LCx, % | 14.7 | 14.8 | 16.5 | 10.6 | |

| Graft, % | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Unknown, % | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| Stenting, % | 88.8 | 90.1 | 87.6 | 90.0 | 0.207 |

| Multivessel disease, % | 40.2 | 38.6 | 40.1 | 42.4 | 0.473 |

| Peak CPK, IU/L | 2269 (1027–4006) | 2304 (1005–4087) | 2242 (1026–4041) | 2345 (1104–3882) | 0.898 |

| Medication at discharge | |||||

| ACEI, % | 44.6 | 46.2 | 44.2 | 43.5 | 0.650 |

| ARB, % | 40.4 | 38.2 | 41.4 | 41.0 | 0.425 |

| Beta-blocker, % | 62.0 | 59.9 | 62.5 | 63.4 | 0.466 |

| Calcium-blocker, % | 13.5 | 13.2 | 13.2 | 14.4 | 0.814 |

| Statin, % | 53.5 | 50.7 | 54.1 | 55.7 | 0.249 |

| Diuretics, % | 24.7 | 22.6 | 26.0 | 24.4 | 0.333 |

| Dual antiplatelet, % | 80.8 | 80.8 | 80.6 | 80.9 | 0.990 |

Categorical variables are presented as a percentage and continuous variables are presented as a median (25–75 percentiles).

ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CAG, coronary angiography; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; LAD, left anterior descending artery;

LCx, left circumflex artery; RCA, right coronary artery; and STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

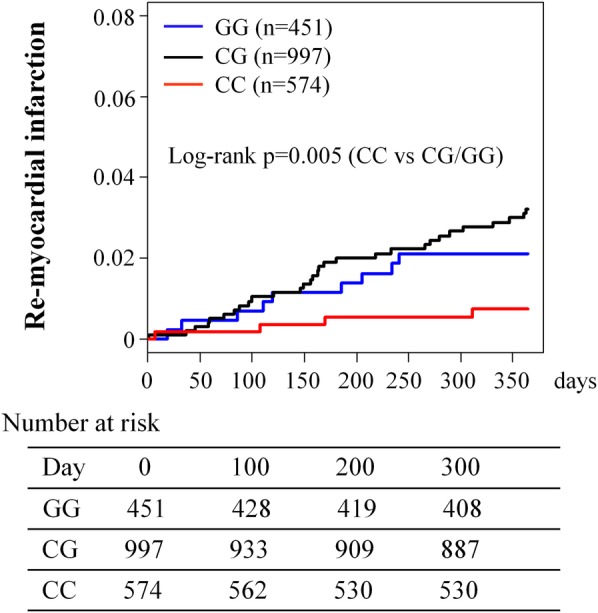

In the primary prevention setting, the rs1333049 C allele was associated with increased susceptibility to AMI (OR 1.20 per C allele increase, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.33, p= 2.3*10−4; and OR 1.38 CC vs CG/GG, 95% CI 1.17 to 1.62, p=8.7*10−5) compared with 1373 healthy Japanese controls (figure 3). The frequencies of the CC, CG and GG genotypes of rs1333049 were 28.4% (574/2022), 49.3% (997/2022) and 22.3% (451/2022), respectively, among the study population, and 22.4% (307/1373), 52.3% (718/1373) and 25.3% (348/1373), respectively, among healthy controls.

Figure 3.

Impact of the rs1333049 genotype on onset and 1 year remyocardial infarction. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; (CC vs CG/GG); (C vs G per allele); ReMI, recurrence of myocardial infarction.

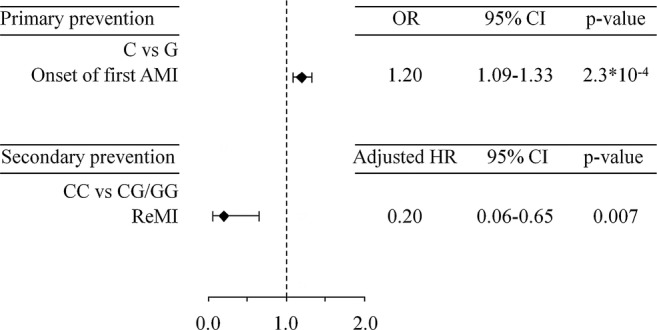

In the secondary prevention setting, 43 ReMI (4 for CC, 30 for CG and 9 for GG genotypes) occurred during a 1-year follow-up period after survival discharge for their first AMI. The Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that the incidence of ReMI differed between patients with the CC and CG/GG genotypes (log-rank p=0.005; figure 2). Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that the CC genotype was associated with a lower risk of ReMI after survival discharge compared with the CG/GG genotypes (adjusted HR 0.20, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.65, p=0.007). Subgroup analysis demonstrated that the association between the rs1333049 CC genotype and a lower incidence of 1 year ReMI was common to all subgroups, and no significant gene–drug interactions were detected (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of the impact of rs1333049 genotype on 1 year remyocardial infarction rate. ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; NA, not assessed due to the insufficient number of events in the subgroup analysis; and STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that, in the secondary prevention setting of AMI, homozygous carriers of the rs1333049 risk allele (CC genotype) on chromosome 9p21 had a reduced incidence of ReMI, whereas the C allele did have conferred susceptibility to their first AMI. This result is of clinical importance because this is the first study to clearly show a change in the susceptibility risk of the 9p21 variant to AMI between before and after the first AMI, namely, between the primary and secondary prevention settings.

Historically, 9p21 SNP was identified as a susceptibility variant of CAD with GWAS using data from the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium in 2007.3 Many other GWAS have also revealed the same association between 9p21 SNP and CAD and/or myocardial infarction.3–8 In addition, one report by Chan et al11 suggested the presence of a common pathway to develop CAD and myocardial infarction via 9p21 SNP. Thus, the 9p21 SNP is now considered as one of the most robust susceptibility variants of myocardial infarction and/or CAD in the primary prevention setting. To date, three major studies have assessed the association between 9p21 genetic variation and ReMI rates after ACS (table 2)12–14: the Italian genetic study and TexGen registry reported a lack of association with ReMI events after early-onset myocardial infarction and ACS (fraction unknown), respectively,13–14 while the GRACE genetic study suggested a susceptibility risk of 9p21 SNPs for ReMI after ACS (STEMI) 27.2%, non-STEMI 43.3%, and unstable angina 29.5%).12 Since Buysschaert et al12 also reported that the statistical significance of the susceptibility risk of 9p21 disappeared after full adjustment for patient background in the GRACE genetic study, it is possible to interpret the results of these three studies as a lack of 9p21 susceptibility to ReMI in post-ACS patients.12–14 These findings are of clinical significance because they suggested a modification of the genetic risk of 9p21 by secondary prevention programmes after ACS. However, these studies are limited to discuss modification of genetic risk with secondary prevention programmes since they only examined the susceptibility impact of 9p21 SNPs to the ReMI without comparison with that to the first AMI (ACS) in their study cohort.

Table 2.

Summary of studies examining the association between 9p21 variants and remyocardial infarction events after acute coronary syndrome

| OACIS registry | GRACE genetic study | Italian genetic study | TexGen registry | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | – | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| Year | – | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

| SNP | rs1333049 | rs1333049 | rs1333040 | rs1333049 |

| Pt number | 2022 | 2942 | 1508 | 2067 |

| Design | Prospective | Prospective | Prospective | Prospective |

| Follow-up | 1 year | 6 months | 9.95 years | 3.2 years |

| Population | Japan | UK, Belgium, Poland | Italy | USA |

| Background disease | MI (STEMI 87.7%, non-STEMI 12.3%) | ACS (STEMI 27.2%, non-STEMI 43.3%, UA 29.5%) | Early-onset MI | ACS (fraction unknown) |

| PCI | 100% | 47.5% | 0% | 63.6% |

| End point | ReMI after survival discharge | ReMI including in-hospital events | ReMI including in-hospital events | ReMI including in-hospital events |

| Conclusion | Low event rate with homozygous carriers of risk allele | High event rate with risk allele carriers (univariate) | No association | No association |

| Replication | None | None | None | None |

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CAD, coronary artery disease; DES, drug-eluting stent; GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events; MI, myocardial infarction; OACIS, Osaka Acute Coronary Insufficiency Study; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; Pt, participants; ReMI, recurrence of myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; UA, unstable angina.

From this point of view, it is noteworthy that the present study clearly showed a change in the 9p21 susceptibility risk to AMI between before and after the first onset of AMI in the same population. In the present study, the results showed that the rs1333049 C allele was associated with onset of the first AMI (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.33, p=2.3*10−4), which was consistent with the results of several previous studies in the primary prevention settings.3––8 Interestingly, however, the present study also demonstrated that patients with the CC genotype had a lower incidence of 1 year ReMI (adjusted HR, 0.20, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.65, p=0.007) as a novel finding. These observations suggested that the risk of the 9p21 variant seen in the primary prevention setting of the present study population was modified in the secondary prevention setting. Although it is speculative, it is considered that modification of genetic risk of the rs1333049 C allele might have unmasked the risk of the rs1333049 G allele in the secondary prevention setting (see online supplementary figure S2). However, it should be discussed why the 9p21 rs1333049 CC genotype was associated with a reduced incidence of ReMI in the present study, while not in the previous three studies.12–14 One possible explanation for this discrepancy between the previous studies and our current study is that we only include patients with post-AMI who were treated with emergent PCI on admission and survived to discharge, whereas all previous studies included all of the patients hospitalised for AMI or ACS and thus include ReMI during the acute stage of ACS as an end point. Considering that ReMI occurring during the acute stage of ACS was most likely associated with lesion-related or procedure-related backgrounds such as reocclusion of the culprit lesion due to a thrombus or mechanical acute closures rather than genetic background, inclusion of these ReMI might have made the interpretation of the results difficult in the previous studies. In addition, limiting patient selection to those treated with primary PCI for the first AMI in the present study might have clearly elucidated the 9p21-treated susceptibility to ReMI in the secondary prevention cohort.

The 9p21 locus is adjacent to the tumour suppressor genes CDKN2A and CDKN2B.8 Although the mechanism by which variation in the 9p21 locus increases AMI susceptibility in the primary prevention setting remains unclear,8 the evidence-based secondary prevention programmes might have masked the susceptibility risk of the 9p21 rs1333049 C allelle to ReMI after ACS in the present study (figure 2), possibly via stabilising coronary plaques.9–14 22–23 Indeed, Do et al24 reported that the impact of 9p21 genetic variation can be modified by increasing the dietary intake of vegetables, suggesting a role of secondary prevention programmes including dietary practice. Thus, further studies are warranted to investigate whether and how secondary prevention programmes with evidence-based medication and lifestyle modification can reduce the risk of ReMI in patients with 9p21 genetic variants in the near future. In particular, the potential interaction of the rs1333049 SNP with secondary prevention medications warrants further investigation, because gene–drug interactions have already been detected in cardiovascular patients treated with warfarin, clopidogrel and statin.25–27

The present study has several limitations that warrant mention. First, since our study population only consisted of patients who provided written informed consent at survival discharge, there may have been selection bias as well as a survival bias since high-risk patients carrying the C allele might have died more frequently than patients with the GG genotype during hospitalisation. Second, the number of ReMI was relatively small and our study lacked a replication cohort to validate our observations. Therefore, replication studies with a larger sample are warranted to confirm our observations. However, it is often difficult to have a validation cohort in a prospective observational study design.28 Indeed, all studies presented in table 2 did not include a replication cohort. Third, therapeutic regiment of AMI varied across the study period. Fourth, data regarding the mechanism and culprit lesion of ReMI were not available. Since ReMI can occur through a variety of mechanisms such as acute stent thrombosis of the culprit lesion, excessive intimal proliferation of stented vessels, and plaque rupture of new atherosclerotic lesions, a detailed analysis for the mechanism of ReMI is ideal. Fifth, patient backgrounds and primary preventive medications were not adjusted in the case–control association study in the primary prevention setting. Finally, it is possible that unmeasured confounding factors influenced the study outcomes due to the inherent nature of observational registry. The data should be interpreted within the context of these potential limitations.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that homozygous carriers of the AMI susceptibility variant rs1333049 SNP C allele on chromosome 9p21 showed a reduced risk of 1 year ReMI after survival discharge, suggesting a modification of genetic susceptibility of AMI with secondary prevention programmes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mariko Kishida, Rie Nagai, Nanase Muraoka, Hiroko Takemori, Akiko Yamagishi, Kumiko Miyoshi, Chizuru Hamaguchi, Hiroko Machida, Mariko Yoneda, Nagisa Yoshioka, Mayuko Tomatsu, Kyoko Tatsumi, Tomoko Mizuoka, Shigemi Kohara, Junko Tsugawa, Junko Isotani, Sachiko Ashibe and all the other OACIS research coordinators and nurses for their excellent assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors participated in the study conception and design, as well as acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the article and its critical revision for important intellectual content, and final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for University and Society Collaboration (#19590816 and #19390215) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Tokyo, Japan.

Competing interests: IK has received research grants and speaker's fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Astellas Pharma, DAIICHI SANKYO COMPANY, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis Pharma and Shionogi.

Ethics approval: The study protocol complied with the Helsinki Declaration and the guidelines for genomic/genetic research issued by the Japanese government. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee of each participating institution.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.White HD, Chew DP. Acute myocardial infarction. Lancet 2008;372:570–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marenberg ME, Risch N, Berkman LF, et al. Genetic susceptibility to death from coronary heart disease in a study of twins. N Engl J Med 1994;330:1041–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samani NJ, Erdmann J, Hall AS, et al. WTCCC and the Cardiogenics Consortium; Genomewide association analysis of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2007;357:443–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McPherson R, Pertsemlidis A, Kavaslar N, et al. A common allele on chromosome 9 associated with coronary heart disease. Science 2007;316:1488–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helgadottir A, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, et al. A common variant on chromosome 9p21 affects the risk of myocardial infarction. Science 2007;316:1491–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myocardial Infarction Genetics Consortium Kathiresan S, Voight BF, Purcell S, et al. Genome-wide association of early-onset myocardial infarction with single nucleotide polymorphisms and copy number variants. Nat Genet 2009;41:334–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schunkert H, König IR, Kathiresan S, et al. CARDIoGRAM Consortium. Large-scale association analysis identifies 13 new susceptibility loci for coronary artery disease. Nat Genet 2011;43:333–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schunkert H, Götz A, Braund P, et al. ; Cardiogenics Consortium. Repeated replication and a prospective meta-analysis of the association between chromosome 9p21.3 and coronary artery disease. Circulation 2008;117:1675–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horne BD, Carlquist JF, Muhlestein JB, et al. Association of variation in the chromosome 9p21 locus with myocardial infarction versus chronic coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2008;1:85–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dandona S, Stewart AF, Chen L, et al. Gene dosage of the common variant 9p21 predicts severity of coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;56:479–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan K, Patel RS, Newcombe P, et al. Association between the chromosome 9p21 locus and angiographic coronary artery disease burden: a collaborative meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:957–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buysschaert I, Carruthers KF, Dunbar DR, et al. A variant at chromosome 9p21 is associated with recurrent myocardial infarction and cardiac death after acute coronary syndrome: the GRACE Genetics Study. Eur Heart J 2010;31:1132–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ardissino D, Berzuini C, Merlini PA, et al. Italian atherosclerosis, thrombosis and vascular biology investigators. Influence of 9p21.3 genetic variants on clinical and angiographic outcomes in early-onset myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:426–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Virani SS, Brautbar A, Lee VV, et al. Chromosome 9p21 single nucleotide polymorphisms are not associated with recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with established coronary artery disease. Circ J 2012;76:950–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hara M, Sakata Y, Nakatani D, et al. Osaka Acute Coronary Insufficiency Study (OACIS) Investigators. Low levels of serum n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are associated with worse heart failure-free survival in patients after acute myocardial infarction. Circ J 2013;1:153–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakatani D, Sakata Y, Suna S, et al. Osaka Acute Coronary Insufficiency Study (OACIS) Investigators. Impact of beta blockade therapy on long-term mortality after ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction in the percutaneous coronary intervention era. Am J Cardiol 2013;111:457–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumoto S, Nakatani D, Sakata Y, et al. Osaka Acute Coronary Insufficiency Study (OACIS) Group. Elevated serum heart-type fatty acid-binding protein in the convalescent stage predicts long-term outcome in patients surviving acute myocardial infarction. Circ J 2013;77:1026–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitamura T, Sakata Y, Nakatani D, et al. Living alone and risk of cardiovascular events following discharge after acute myocardial infarction in Japan. J Cardiol 2013;62:257–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Usami M, Sakata Y, Nakatani D, et al. Clinical impact of acute hyperglycemia on development of diabetes mellitus in non-diabetic patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiol 2014;63:274–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.No authors listed. Nomenclature and criteria for diagnosis of ischemic heart disease. Report of the Joint International Society and Federation of Cardiology/World Health Organization task force on standardization of clinical nomenclature. Circulation 1979;59:607–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohnishi Y, Tanaka T, Ozaki K, et al. A high-throughput SNP typing system for genome-wide association studies. J Hum Genet 2001;46:471–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kushner FG, Hand M, Smith SC, Jr, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2009 Focused Updates: ACC/AHA Guidelines for the Management of Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (updating the 2004 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update) and ACC/AHA/SCAI Guidelines on Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (updating the 2005 Guideline and 2007 Focused Update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines . Circulation 2009;120:2271–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsunoda R, Sakamoto T, Kojima S, et al. Recurrence of angina pectoris after percutaneous coronary intervention is reduced by statins in Japanese patients. J Cardiol 2011;58:208–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Do R, Xie C, Zhang X, et al. INTERHEART investigators. The effect of chromosome 9p21 variants on cardiovascular disease may be modified by dietary intake: evidence from a case/control and a prospective study. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1001106 (accessed 11 Nov 2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein TE, Altman RB, Eriksson N, et al. International Warfarin Pharmacogenetics Consortium. Estimation of the warfarin dose with clinical and pharmacogenetic data. N Engl J Med 2009;360:753–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, et al. French Registry of Acute ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (FAST-MI) Investigators. Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 2009;360:363–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Link E, Parish S, Armitage J, et al. SEARCH Collaborative Group. SLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy—a genomewide study. N Engl J Med 2008;359:789–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ginsburg GS, Shah SH, McCarthy JJ. Taking cardiovascular genetic association studies to the next level. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:930–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.