Abstract

Objective

To confirm the accuracy of a diagnostic questionnaire for carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) when presented via a public website rather than on paper.

Design

Prospective comparison of the probability of CTS as assessed by the web-based questionnaire at http://www.carpal-tunnel.net with the results of nerve conduction studies.

Setting

Subregional neurophysiology laboratory serving a population of 700 000 in East Kent, UK.

Participants

2821 individuals who were able to complete an online diagnostic questionnaire out of 4899 referred for initial diagnostic testing for new presentations with suspected CTS from April 2011 to March 2013. No exclusions were made on grounds of age, gender or coincident pathology.

Main outcome measure—nerve conduction results confirming CTS. The severity of median nerve impairment demonstrated was also assessed using a validated neurophysiological scale.

Results

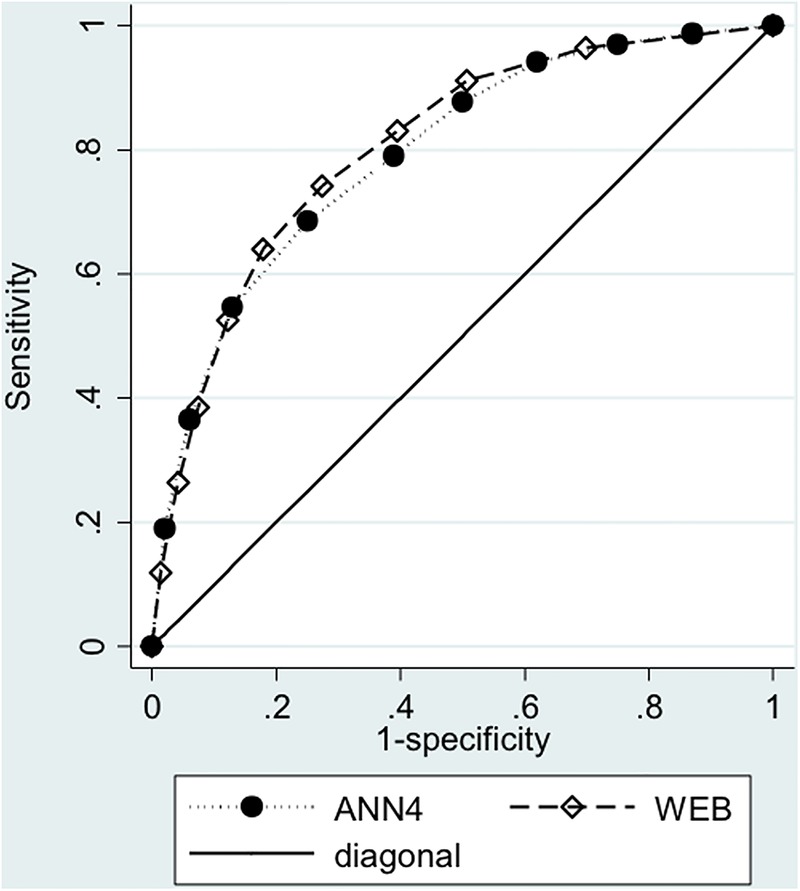

The web-based questionnaire accurately estimates the probability of CTS being confirmed on nerve conduction studies. Using a website diagnostic score of ≥40% as an example cut-off value the questionnaire achieves 78% sensitivity and 68% specificity in predicting the finding of evidence of CTS on nerve conduction studies. The web-based version of the diagnostic questionnaire was as accurate as the original paper version with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.79. There was also a significant correlation between the diagnostic score given by the website and the severity of CTS with higher scores being associated with greater nerve dysfunction (r=0.3, p<0.00001).

Conclusions

Completion of the symptom questionnaire on the website by patients at home provides a prediction of the likelihood of CTS which is sufficiently accurate to be used in initial planning of investigation and treatment.

Keywords: Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, Diagnosis, Sensitivity and Specificity, World Wide Web, Questionnaire

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Prospective design.

Large numbers.

Objective confirmation of diagnosis using best available current methods.

Unselected patient population.

Lack of blinding.

Introduction

The diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is often straightforward, requiring no more than listening to the patient's description of the characteristic timing and distribution of the symptoms and a focused examination of the hands to look for obvious signs. Nevertheless there remains no reliable ‘gold standard’ test for the diagnosis and an extensive literature exists debating the relative merits of clinical diagnosis, nerve conduction studies (NCS), imaging methods and response to treatment as elements of the definition for the syndrome. NCS and imaging produce results which can be quantified and analysed for their diagnostic properties but studies of clinical diagnosis, which are comparatively rare, generally approach it as a binary opinion—the patient either does or does not have, CTS. This does not fairly represent the subtlety of clinical opinion which encompasses a range of certainty rather than being an absolute. Human beings however are rarely able to express their degree of certainty consistently in numerical form for analysis. We have been interested for some years in whether the answers to a questionnaire relating to the symptoms could be analysed mathematically to arrive at an estimate of the probability of CTS, based on the same information used by clinicians, but which would be reproducible and quantifiable so that it could be compared with the results of diagnostic tests.

Interest in standardised questionnaires for diagnosis is not new and some questionnaires have been shown to achieve good agreement with conventional clinical diagnosis for common conditions, for example, in asthma1 or restless legs syndrome2 but these tools are not widely available to patients to use unaided.

An early version of our diagnostic questionnaire achieved 79% sensitivity and 55% specificity for the diagnosis of CTS when the result of NCS was used as the reference standard.3 We refined and extended the questionnaire and by 2011 the paper version had grown to six pages and improved to 96% sensitivity and 50% specificity in predicting the NCS result when tuned to optimise sensitivity in order to avoid missing treatable disease.4 Not only was the paper questionnaire cumbersome but the mathematical methods used to analyse the answers—a logistic regression model and an artificial neural network—required the aid of a computer to calculate the probability of CTS. We therefore created a website on which patients could complete the questionnaire and which would perform the calculations immediately after completion. Our assessments of the performance of the questionnaire however had been made using the paper version and we could not be sure that it would perform in the same way when presented in online format. This study therefore prospectively analyses the diagnostic accuracy of the web-based version of the questionnaire, again using the results of NCS as the reference standard for CTS.

Methods

The collection of a standardised clinical history by questionnaire has been standard practice in the Canterbury department of clinical neurophysiology for 20 years and it was not considered necessary to seek either ethics committee approval or written patient consent for transferring this process of data collection from paper to the website. Completion of the questionnaire on the web takes 20–30 min. The website questionnaire contains a variety of questions which may or may not be of use in making a diagnosis of CTS as we have experimented with a large number of variables at different times in the mathematical models. Although in classical logistic regression it is possible to prune variables which prove to be of limited use in the overall model it is much harder to do this for the neural network model and the entire historically developed question set is therefore still collected. There are also some questions in the overall website questionnaire which are there to support other studies rather than being purely included for diagnostic purposes. Patients retained the option of completing the paper form of the questionnaire if they did not wish to use the web version. The analysis of the anonymised data for this study was however approved by the regional ethics committee.

Patients referred for investigation of possible carpal tunnel syndrome to the subregional department of clinical neurophysiology in Canterbury, Kent, UK between 1 April 2011 and 1 April 2013 were invited, in their appointment letter, to visit the website at http://www.carpal-tunnel.net prior to their appointment and to complete the questionnaire. To do this, patients had to create a user account on the website but we recommended that they create a user identity which did not reveal who they were to third party observers viewing interactions on the site. We provided them, also in the neurophysiology appointment letter, with a reference number to be entered into the site registration page which would identify them uniquely to us. The key data table linking these reference numbers to patient identities is not stored anywhere in the website but is kept in the internal computerised records of the neurophysiology department within the secure boundaries of the hospital IT systems.

On attending the neurophysiology department, patients were asked whether they had been able to complete the questionnaire on the website and those who had not been able to do so were given the original paper version to complete. All patients then had NCS performed for CTS according to guidelines published by the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine.5 The nerve conduction results were graded using the Canterbury severity scale for CTS,6 which represents the changes in sensory and motor nerve conduction velocities and amplitudes as a numerical scale increasing in severity from 0 (no abnormality) to 6 (extremely severe CTS). No exclusions were applied on grounds of age, gender or coincident pathology.

In order to work with the patient rather than the hand as the unit of analysis each patient was classified using the nerve conduction results as either CTS, if either hand showed at least grade 1 CTS, or normal. The diagnostic scores produced by the website were then compared against the presence or absence of CTS and also, in a secondary analysis, against the neurophysiological severity of the worst hand. Finally, as 6% of patients failed to attend our clinic after completing the web questionnaire, we looked at the distribution of website diagnostic scores to see if this subpopulation differed from the patients who did attend for testing.

The web-based questionnaire does not return a binary verdict—CTS, yes or no—but a percentage probability of CTS. The sensitivity and specificity of the questionnaire can therefore be tuned to favour the detection of more disease or the exclusion of more patients who do not prove to have CTS by adjusting the score which is taken as indicating CTS. This variable diagnostic performance was calculated across the full range of scores by constructing a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for comparison with that derived for the paper questionnaire previously. The relationship between the web questionnaire score and the neurophysiological severity of CTS in the worst hand of patients who did have evidence of CTS was assessed using Pearson correlation. The website scores of patients who did, and did not, attend for testing were compared with non-parametric tests as the scores are not normally distributed. Statistical analyses were performed with STATA (StataCorp) and Statistica (Statsoft Inc).

Results

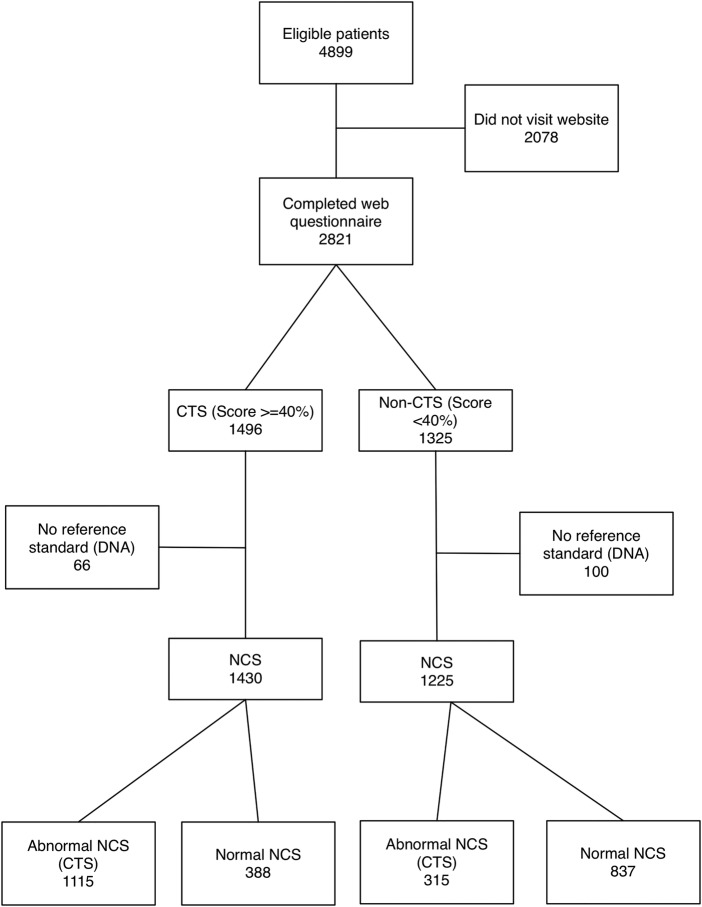

During the 2 years of the study period a total of 6556 nerve conduction tests were requested for CTS. We excluded from the analysis patients who already had known CTS prior to visiting the website, those having tests for follow-up purposes or who had already had treatment for one hand and were returning for management of the second. This left 4899 patients who were referred during their initial presentation with suspected CTS. Of these 2821 (58%) completed the website questionnaire before testing and of this group 166 (5%) then failed to actually attend or cancelled their appointments. Referrals came predominantly (82%) from primary care physicians. Patients who completed the questionnaire were predominantly female (1884/2821=67% female), with a mean age of 54.2 years as expected from the epidemiology of CTS. The 166 patients who failed to attend for testing having completed the questionnaire were younger, average age 49 years. The patients who did not complete the questionnaire online tended to be slightly older, mean age 58 years, but had a similar profile of NCS results and symptom severity when tested with 43% having normal NCS.

The diagnostic performance of the web-based questionnaire is summarised in the ROC curve shown in figure 1 where one of the ROC curves for the paper version of the questionnaire in 2640 prospectively assessed patients is also shown for comparison.4 The two curves are almost indistinguishable and the changes to the questionnaire involved in presenting it on a website do not appear to have altered its diagnostic properties.

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curve illustrating the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the website questionnaire for neurophysiologically defined carpal tunnel syndrome with varying cut-off scores from 0% to 100% (diamonds—WEB). For comparison the equivalent curve for the paper version of the questionnaire is shown (circles—ANN4). The area under these curves is 0.79. The diagonal line would indicate a test with no ability to discriminate between disease and normal.

To demonstrate the possible utility of the website, table 1 shows the proportions of patients in 10% bands by website diagnostic score who prove to have CTS and also the distribution of website scores in the population of patients referred to the Canterbury neurophysiology department for a suspected diagnosis of CTS. 26% of all referrals have website diagnostic scores <20% and 81% of this group of patients have normal median NCS.

Table 1.

Numbers of subjects categorised by diagnostic score on the website in 10% bands, the percentage of the total patient population falling in each of these bands and the number and percentage of patients in each band showing evidence of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) on nerve conduction studies

| Website score (%) | Subjects | Total (%) | CTS | Group (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–9 | 401 | 15 | 54 | 13 |

| 10–19 | 300 | 11 | 79 | 26 |

| 20–29 | 251 | 9 | 122 | 49 |

| 30–39 | 273 | 10 | 133 | 49 |

| 40–49 | 230 | 9 | 130 | 57 |

| 50–59 | 270 | 10 | 195 | 72 |

| 60–69 | 235 | 9 | 187 | 80 |

| 70–79 | 250 | 9 | 206 | 82 |

| 80–89 | 218 | 8 | 187 | 86 |

| >90 | 227 | 9 | 210 | 93 |

| Total | 2655 |

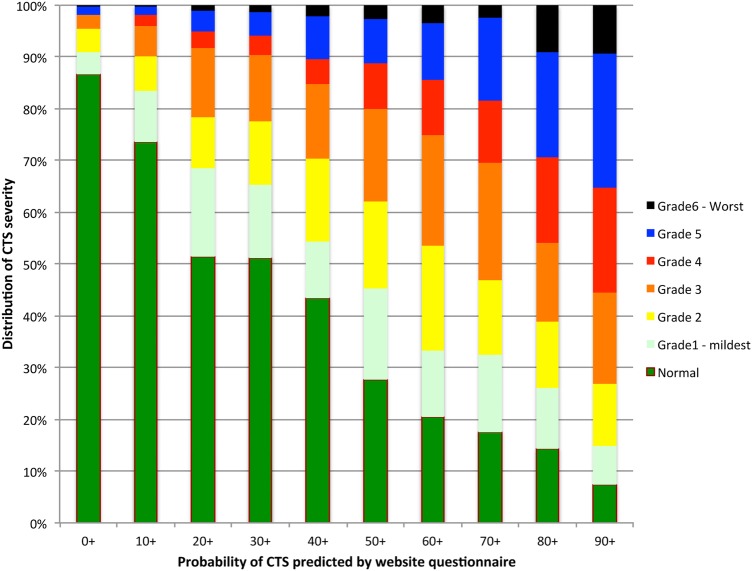

Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between the website score and the severity of CTS demonstrated in the worst hand. Each column shows the proportions of patients in one range of website diagnostic scores who proved to have NCS of each grade of severity, normalised to 100%. Thus, of 401 patients with a website diagnostic score of <10%, 87% had normal NCS, 4% grade 1, 4% grade 2, 2% grade 3, 0.2% grade 4, 1% grade 5 and 0.2% grade 6. The relationship is highly statistically significant but weak (Pearson r=0.30, p<0.0001).

Figure 2.

The relationship between the website score and the severity of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) demonstrated in the worst hand. Each column shows the proportions of patients in one 10% range of website diagnostic scores who proved to have nerve conduction studies (NCS) of each grade of severity, normalised to 100%. Thus, of 401 patients with a website diagnostic score of <10%, 87% had normal NCS, 4% grade 1, 4% grade 2, 2% grade 3, 0.2% grade 4, 1% grade 5 and 0.2% grade 6.

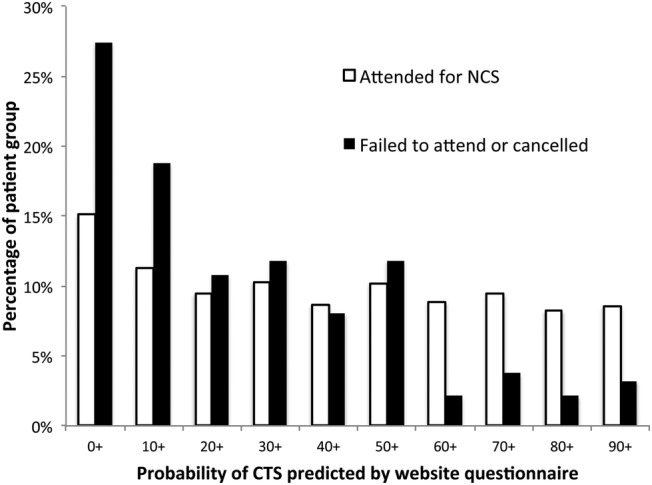

Figure 3 shows the distribution of website scores in the 166 patients who did not attend for testing compared to that of the 2655 who did attend. There is a marked tendency for the non-attenders to have lower scores (Mann Whitney U test, adjusted Z=−4.57, p<0.00001).

Figure 3.

Distributions of website diagnostic scores (in 10% bands) in patients who attended for testing (white bars), compared to those who failed to attend (black bars). CTS, carpal tunnel syndrome.

Although a variety of cut-off points could be chosen from the ROC curve (figure 1) to trigger management decisions we have illustrated the patient categorisation which would be achieved if a website score of 40% were used to diagnose CTS in figure 4.

Figure 4.

STARD flow diagram for the study using an arbitrary cut-off score on the website questionnaire of 40% as indicating carpal tunnel syndrome. CTS, carpal tunnel syndrome; NCS, nerve conduction studies.

Discussion

The website questionnaire performs as expected in predicting neurophysiological confirmation of the diagnosis of CTS. It has a slight overall tendency to underestimate the probability of disease except with the very highest scores. Thus a group of patients with scores from 0% to 9% (average 5%) turn out to have a 13% prevalence of neurophysiological abnormalities consistent with CTS while a group with an average score of 95% has a 92% prevalence of CTS. The explanation for this lies partly in the fact that we are comparing the website predictions against NCS which are known to have significant false-positive and false-negative rates in the diagnosis of CTS. Many estimates of the false-negative and false-positive rates of NCS for CTS have been made, one study for example finding 30% false-negative and 18% false-negative rates in comparison to clinical diagnosis,7 but in the absence of any true gold standard for the diagnosis of CTS it is impossible to know the true rates. At the lower end of the range of website scores, the great majority of NCS abnormalities are mild (figure 2) and it is likely that, in a significant proportion of these patients, their clinical problem is not CTS, even if they do have slight evidence of median nerve impairment on NCS. Conversely at the higher end of the range it is likely that many patients with very high symptom scores are examples of false-negative NCS. We have recently begun examining these high scoring, NCS-negative patients with ultrasound imaging and some of them do show evidence of CTS using that method.

There are some methodological limitations to the current study. The patients were recruited because their general practitioner was sufficiently suspicious of a possible diagnosis of CTS that they were referred for neurophysiological testing and they are therefore not necessarily representative of all patients with hand and arm symptoms and the results presented here may not be achieved by patients who have simply stumbled on the website by themselves. Second this is not a blinded study. The patients themselves saw their website diagnostic score as soon as they completed the questionnaire and were thus immediately informed of the likelihood of CTS before attending for testing. We received some telephone calls from patients with low scores during the study period asking whether it was still worth them attending for the test if it was unlikely to show evidence of CTS. We tried to encourage these patients to attend anyway as we were trying to assess the performance of the site in a full range of patients but there is a significant excess of low-scoring patients in the group who failed to attend and it is likely that, despite our efforts to encourage people to attend, directing patients to the website has already led some low-scoring patients to decide for themselves not to attend. Conversely, patients with high scores were more likely to attend. We also did not blind the technical staff performing the NCS to the website scores because NCS are a relatively objective measure and the results are not likely to have been greatly influenced by the operator’s knowledge of the website scores.

The role of NCS in the diagnosis and management of CTS has been the subject of much debate and a view that they are diagnostically superfluous, or even contraindicated, when the clinician is certain of the diagnosis is widespread in hand surgery circles at least in the UK (ref BHS guidelines), though in the USA widely agreed guidelines recommend the use of NCS in all cases before surgery. The Ontario hand surgery group have made the Bayesian argument that, when the clinical probability of CTS is either very high or very low, then performing NCS is not likely to change the post-test probability of CTS significantly, whatever the result. They proposed a clinical scoring system, the CTS-7, which, like our website questionnaire, is intended to quantify the clinical certainty of diagnosis in CTS so that an approach of only testing patients with intermediate probabilities of CTS could be adopted.8 This tool however has not been prospectively evaluated in real patients and is not available for patients to use on the internet. We have compared a simple scoring system proposed in the UK9 against our models and found it to be significantly less accurate in predicting CTS.4 A similar method to ours, using a logistic regression analysis, has been adopted in a South American patient group and claims good diagnostic performance but has not yet been prospectively evaluated in new patients and again is not readily available to the general public.10 None of these alternate tools have yet demonstrated that their results are related to the neurophysiological severity of CTS, nor to the prognosis for surgical or conservative treatment.

Confirming or refuting the diagnosis is not the only, or even the primary, reason for carrying out NCS in suspected CTS. The evaluation of the physiological severity of nerve damage, for prognosis and for follow-up when treatment is unsuccessful, and the detection of other nerve problems such as underlying polyneuropathy are probably more important in clinically obvious cases than the diagnostic result of the test.

We believe that we have created a tool which can be used by patients with hand symptoms to derive a baseline probability that they have CTS and which is sufficiently accurate to be used to guide initial patient management. Units wishing to restrict the use of NCS for diagnosis of patients in whom there is uncertainty can now obtain an objective measure of the clinical likelihood of CTS on which to base decisions about investigation and treatment. We recommend that, whenever CTS is suspected in primary care, the patient should be directed to carpal-tunnel.net to complete the questionnaire at home, or, if unable to access the internet themselves, aided to complete the questionnaire by ancillary staff in the practice. Management can then begin with an objective probability that CTS is the correct diagnosis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JDPB reported, interpreted and graded all of the nerve conduction studies, extracted and collated the questionnaire data from the website and neurophysiology department databases and wrote the first draft of the main body text of the article. PW devised the neural network algorithm used to analyse the patient input questionnaire data and contributed to the writing of the main body text. SR devised the logistic regression model used to analyse the patient input questionnaire data, carried out the statistical assessment of the extracted data for this paper and contributed to editing the body text.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Surrey Borders NRES Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Jenkins MA, Clarke JR, Carlin JB, et al. Validation of questionnaire and bronchial hyperresponsiveness against respiratory physician assessment in the diagnosis of asthma. Int J Epidemiol 1992;25:609–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen RP, Burchell BJ, MacDonald B, et al. Validation of the self-completed Cambridge-Hopkins questionnaire (CH-RLSq) for ascertainment of restless legs syndrome (RLS) in a population survey. Sleep Med 2009;10:1097–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bland JDP. The value of the history in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Br 2000;25B:445–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bland JD, Weller P, Rudolfer S. Questionnaire tools for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome from the patient history. Muscle Nerve 2011;44:757–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jablecki CK, Andary MT, Floeter MK, et al. Practice parameter: electrodiagnostic studies in carpal tunnel syndrome. Neurology 2002;58:1589–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bland JDP. A neurophysiological grading scale for carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle Nerve 2000;23:1280–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atroshi I, Gummesson C, Johnsson R, et al. Diagnostic properties of nerve conduction tests in population-based carpal tunnel syndrome. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003;4:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham B, Regehr G, Naglie G, et al. Development and validation of diagnostic criteria for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am 2006;31A:919–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamath V, Stothard J. A clinical questionnaire for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Br 2003;28B:455–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gomes I, Becker J, Ehlers JA, et al. Prediction of the neurophysiological diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome from the demographic and clinical data. Clin Neurophysiol 2006;117:964–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.