Abstract

Macrovascular complications are common in diabetic hypertensive patients. Appropriate antihypertensive therapy and tight blood pressure control are believed to prevent or delay such complication.

Objective

To evaluate utilization patterns of antihypertensive agents and blood pressure (BP) control among diabetic hypertensive patients with and without ischemic heart disease (IHD).

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of all diabetic hypertensive patients attending Al-watani medical center from August 2006 until August 2007. Proportions of use of different antihypertensive drug classes were compared for all patients receiving 1, 2, 3, or 4 or more drugs, and separately among patients with and without IHD. Blood pressure control (equal or lower 130/80 mmHg) was compared for patients receiving no therapy, monotherapy, or combination therapy and separately among patients with and without IHD.

Results

255 patients were included in the study; their mean age was 64.4 (SD=11.4) years. Sixty one (23.9%) of the included patients was on target BP. Over 60% of the total patients were receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI)/ angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), followed by diuretics (40.8%), calcium channel blockers (25.1%) and beta-blockers (12.5%). The majority (> 55%) of patients were either on mono or no drug therapy. More than 55% of patients with controlled BP were using ACE-I. More than half (50.8%) of the patients with controlled BP were on combination therapy while 42.3% of patients with uncontrolled BP were on combination therapy (p=0.24). More patient in the IHD achieved target BP than those in non-IHD group (p=0.019). Comparison between IHD and non-IHD groups indicated no significant difference in the utilization of any drug class with ACE-I being the most commonly utilized in both groups.

Conclusions

Patterns of antihypertensive therapy were generally but not adequately consistent with international guidelines. Areas of improvement include increasing ACE-I drug combinations, decreasing the number of untreated patients, and increasing the proportion of patients with controlled BP in this population.

Keywords: Hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus, Drug Utilization, Palestine

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that 2.7% of Palestinians living in West-Bank have hypertension and 2.1% have diabetes mellitus.1 Although, no epidemiological data are available about Palestinians who have diabetes mellitus and hypertension together, the prevalence of hypertension, in general, is few times greater in patients with diabetes mellitus than in matched non-diabetic individuals.2 The major adverse outcomes of diabetes mellitus are a result of vascular complications, both, at the microvascular (retinopathy, nephropathy or neuropathy) and macrovascular levels (coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular and peripheral vascular disease).3,4 These vascular complications are augmented by the co-existence of hypertension.5 Serious cardiovascular events are more than twice as likely in patients with diabetes and hypertension as with either disease alone.6 To minimize and delay the vascular complications among diabetic hypertensive patients, a tight control of blood pressure (BP) and glucose levels is required.4,7 Although studies have indicated that tight blood glucose control can reduce microvascular end points6,8,9, no experimental studies have yet shown a causal relationship between improved glycemic blood glucose control and reduction in serious cardiovascular outcomes. In contrast, blood pressure level control is more effective than glycemic control in reducing risk for cardiovascular and microvascular events and that is why management of hypertension among patients with diabetes mellitus should be prioritized.10 However, studies consistently demonstrate that most diabetic patients do not achieve recommended levels of BP control, and the majority have a BP of >140/90 mmHg.11-13

There are a growing number of pharmacological treatment options for patients with hypertension. However, the choice of antihypertensive drug class is influenced by many factors such as the presence of co-morbid conditions. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC) stated that angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) is an important component of most regimens to control BP in diabetic patients. In those patients, ACE-I may be used alone, but much more effective when combined with thiazide-type diuretic or other antihypertensive drugs.14 The JNC 7th report recommended that BP in diabetics be controlled to levels of 130/80 mm Hg or lower. Rigorous control of BP is paramount for reducing the progression of diabetic nephropathy to end stage renal disease (ESRD). In hypertensive patients with ischemic heart disease (IHD), the JNC 7th report recommended the use of beta blockers (BB) unless contraindicated. If BB therapy was inadequate or contraindicated, either long acting dihydropyridine or nondihydropyridine-type calcium channel blockers (CCB) may be used.14

The primary objectives of this project were (1) to evaluate and compare utilization of antihypertensive therapies according to JNC 7th report for diabetic patients with and without IHD, and (2) to assess BP control among diabetic hypertensive patients.

METHODS

Settings and Study Design

This is an observational retrospective study conducted at Al-Watani governmental hospital and medical center, the largest non-surgical medical center in north Palestine with in and out-patient community medical services. Practitioners at this center were a combination of specialized and general physicians.

Participants and Data Collection

Data were collected for the period of August 1, 2006 to August 1, 2007. All inpatients as well as all outpatients from clinics were screened. We used the medical records of the patients to obtain diagnostic information, demographic information, laboratory test results, vital signs, and prescription drug use. All aspects of the study protocol, including access to and use of the patient clinical information, were authorized by the medical ethics committee and the local health authorities. All diabetic hypertensive patients seen during the study period were investigated.

History of Ischemic heart disease was obtained from patients’ medical files. Patients with history of angina pectoris or myocardial infarction or any diagnosis of coronary artery disease were considered to have IHD. Reduced renal function or renal impairment was defined as creatinine clearance (CrCl) ≤ 60 ml/min. This cut off point was used by JNC 7th report to guide therapy for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Creatinine clearance was calculated using Cockcroft-Gault equation. To better study the use of ACE-I specifically for diabetes, patients with any record of an inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of chronic heart failure (CHF) were excluded. Furthermore, patients with End Stage Renal Disease (GFR<15 mL/min) were excluded to avoid misinterpretation of drug use.

Outcome Measure

Elevated or non-target BP was defined as greater than or equal to130/80 mmHg, according to the JNC 7th report.14 Antihypertensive drug classes (betablockers, calcium channel blockers, thiazide/ loop diuretics, ACE-I/ARB, and alpha-blockers) were recorded. The number of antihypertensive drugs being prescribed was tabulated. We classified patients with any prescriptions for ACEI or ARB as ACEI users and classified patients with any prescriptions for thiazide or loop diuretics as diuretic users. The proportion of use of these antihypertensive drug classes, among patients with 1, 2, 3, or 4 or more drugs, was tabulated for all patients. We present the patterns of use of antihypertensive drugs among all patients overall, and in sub-groups of patients on 1, 2, 3, or 4 or more drugs. We compared the proportions of drug class use among patients with and without IHD.

Statistical Analysis

Chi square test was used to test significance between categorical variables while the independent samples t-test was used to test for significance between continuous variables. Data were expressed as mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and as frequency for categorical variables.

RESULTS

During the study period, 340 consecutive diabetic hypertensive patients were identified. Eighty five patients were excluded because they have CHF and/or ESRD. The 255 who met the inclusion criteria were 110 (43.1%) males and 145 (56.9%) females. The mean age of the included patients was 64.58 (SD=11.40) years. The most recently recorded values of systolic, diastolic BP and random blood glucose level were 151.17 (SD=29.40); 86.22 (SD=13.06) mmHg and 257.82 (SD=131.14) mg/dL respectively. The mean CrCl of the patients was 100.24 (SD=73.1) mL/min with 79 patients had reduced renal function (CrCl<60 mL/min). The average number of chronic diseases present among the study patients was 2.83 (SD=0.7). The recommended target BP of equal or lower 130/80 mmHg was achieved in only 61 (23.9%) patients. A total of 109 (42.7%) patients (group I) were having history of IHD while 146 (57.3%) were not (group II). Table 1 shows the clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population and compares these characteristics between patients with and without IHD. No significant difference in the average number of antihypertensive medication was found between patients with and without IHD was found (1.5 SD=0.83 versus 1.4 SD=0.8, p=0.29). However, significantly (p=0.019) more patients with IHD (31.2%) were on target BP than patients without IHD (18.5%).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with and without IHD.

| Variables | Total N = 255 | Group (I) IHD (+) n = 109 | Group (II) IHD (-) n = 146 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.4 ± 11.39 | 65.5± 11.4 | 63.9± 11.4 | 0.25 |

| Gender: male | 110 (43.1%) | 53 (48.6%) | 57 (39%) | 0.12 |

| CrCl (<60 ml/ min) | 79 (31%) | 29 (26.6%) | 50 (34.2%) | 0.19 |

| Number of chronic diseases | 2.83 ± 0.7 | 3.31± 0.57 | 2.47± 0.57 | < 0.001 |

| Duration of diabetes mellitus(years) | 11.7 ± 8.8 | 12± 9.0 | 11.4 ± 8 | 0.66 |

| Duration of hypertension (years) | 7.2 ± 7.5 | 6.6 ± 7.8 | 7.6 ± 7.2 | 0.39 |

| Patients on target BP (< 130/ 80 mmHg) | 61 (23.9%) | 34 (31.2%) | 27 (18.5%) | 0.019 |

| Random blood glucose (mg/dl) | 257.8 ±131.1 | 249.2 ± 110.2 | 264.1 ± 144.3 | 0.35 |

| Number of antihypertensive medications | 1.42 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.83 | 1.4 ± 0.8 | 0.29 |

CrCl = creatinine clearance, IHD = ischemic heart disease, BP = blood pressure. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency (%) while continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were tested using Chi-square while continuous variables were tested using independent samples t test.

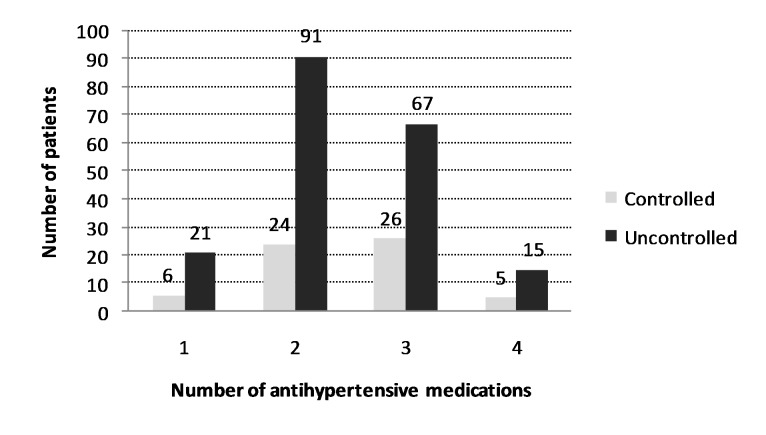

Of the study patients, 228 (89.4%) were treated with antihypertensive drugs, whereas 27 (10.6%) were solely on non-pharmacological interventions. Mono-therapy was prescribed for 115 (45.09%), and combination for 113 (44.31%) patients; of these, two-drug regimen in 93 (82.30%), three-drug regimen in 18 (15.92%), and four drug regimen in 2 (1.76%) patients (Table 2). A total of 363 antihypertensive medications were prescribed for the 255 patients. The average number of antihypertensive medications prescribed for the patients was 1.42 (SD=0.8) (range: 0 to 4) and was positively correlated with the duration of DM (p<0.001), duration of HTN (p=0.049), and number of chronic diseases (p<0.0001) but not with age (p=0.16). More than half (50.8%) of the patients with controlled BP and 42.3% of the patients with uncontrolled BP were using combination therapy; this difference, however, was insignificant (p=0.3), (Figure 1). Distribution of patients based on BP control and number of antihypertensive medication utilized is shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Overall pattern of antihypertensive therapy.

| Drug class | Number of patients with target BP having the medication* | Total Number of drugs (%) | Mono therapy | Combination therapy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One n= 115 | Two n= 93 | Three n= 18 | Four n= 2 | |||

| CCB | 14 (23%) | 6 (1.6) | 10 | 37 | 15 | 2 |

| ACEIs / ARB | 34 (55.7%) | 64 (17.6) | 69 | 70 | 16 | 2 |

| BB | 11 (18%) | 157 (43) | 9 | 15 | 6 | 2 |

| Diuretics | 31 (50.8%) | 32 (8.8) | 27 | 61 | 14 | 2 |

| α-blockers | 1 (1.6%) | 104 (28.7) | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Total Number of drugs | 363 (100) | 115 | 186 | 54 | 8 | |

n= total number of patients.

ACEIs/ ARB = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/ angiotensin receptor blocker. BB = β-blocker, CCB = calcium channel blocker,

Total exceeds 100% because data are overlapping due to multiple use of medication.

Figure 1.

Distribution of blood pressure (BP) control based on the number of anti-hypertensive medications used

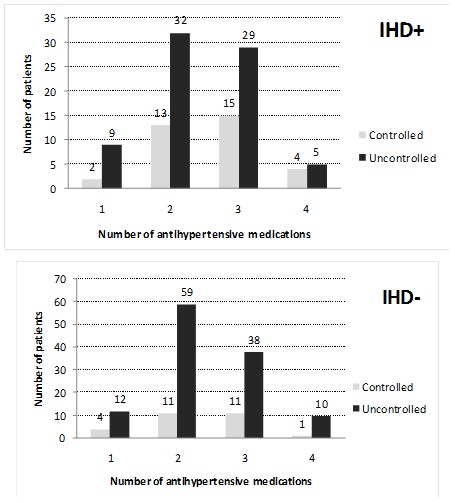

Figure 2.

Distribution of blood pressure (BP) control based on the number of anti-hypertensive medications used stratified by the presence (+) or absence (-) of ischemic heart disease (IHD).

The most commonly antihypertensive drug classes utilized by the patients were ACE-I (157, 43%) followed by diuretics (104, 28.7%) and CCB (64, 17.6%). Overall utilization of antihypertensive drug classes is shown in Table 2. Monotherapy was the most common mode of therapy among the patients (115, 45.09%). ACE-I was used as a monotherapy in 69 (60%), diuretics in 27 (23.48%), CCB in 10 (8.7%) and BB in 9 (7.8%) patients. The two-drug combination regimen was prescribed in 93 patients. The most common 2-drug combination was “ACE-I with others” which was utilized by 70 (75.26%) patients. Overall, more than half of the patients with controlled BP were on ACE-I and/ or diuretics (Table 2).

Antihypertensive pattern and medications prescribed for patients with or without IHD were investigated. Patients with IHD were prescribed a total of 162 antihypertensive medications, an average of 1.49 (SD=0.83) medications per patient. A total of 11 (10.1%) patients were on non-pharmacologic therapy, 45 (41.3%) on monotherapy and 53 (48.6%) were on combination therapy. ACEI was the most commonly (22.9%) prescribed drug class as monotherapy in this group of patients. ACE-I was the most commonly (62.5%) prescribed drug in combination therapy in group (I) patients. A total of 201 antihypertensive medications were prescribed to patients without IHD, an average of 1.41 (SD=0.78) per patient. A total of 16 (11%) patients were on non pharmacological therapy, 70 (47.9%) on mono therapy and 60 (41.1%) patients were on combo therapy. ACE-I (30.1%) were the most commonly prescribed monotherapy drug for patients in group (II). ACE-I was the most commonly (63.2%) prescribed drug in combination therapy in on the number of anti-hypertensive medications used patients without IHD. There was no significant difference in the overall utilization of any drug class and patients in either group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Patterns of use of antihypertensive drugs among patients with and without IHD

| Drug class, N (%) | IHD (+) | IHD (-) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (%) n=109(100.0) | 1 Drug n= 45 (41.3) | ≥ 2 Drugs n= 53 (48.6) | Overall (%) n=146(100.0) | 1 Drug n=70(47.9) | ≥ 2 Drugs n=60(41.1) | |

| ACEIs / ARB | 65(59.6) | 25(55.6) | 40(75.5) | 92(63) | 44(62.9) | 48(80) |

| BB | 18(16.5) | 4(8.9) | 14(26.4) | 14(9.6) | 5(7.1) | 9(15) |

| CCB | 33(30.3) | 5(11.1) | 28(52.8) | 31(21.2) | 5(7.1) | 26(43.3) |

| Diuretics | 44(40.4) | 11(24.4) | 33(62.3) | 60(40.1) | 16(22.9) | 44(73.3) |

| α-blockers | 0.0(0.0) | 0.0(0.0) | 0.0(0.0) | 6 (4.1) | 0.0(0.0) | 4(6.7) |

| Total number of drugs | 160 | 45 | 115 | 203 | 70 | 133 |

Notes: 1. a group of 27 patients who were not on pharmacologic therapy were not included in the analysis.

2. “n” represents the number of patients.

3. IHD= ischemic heart disease, ACEIs/ ARB = angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/ angiotensin receptor blocker. BB = β-blocker, CCB = calcium channel blocker,

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the patterns of antihypertensive drug therapy in diabetic hypertensive patients with and without IHD. Our study revealed that more than half (55%) of the total patients were on single or no antihypertensive therapy and that less than one third of the patients were on target BP. This study also showed that more than one third of the total patients had IHD suggesting that screening and preventive therapies for coronary artery diseases among diabetic hypertensive patients are important to decrease morbidity and mortality among this category of patients. This study also showed that the majority of patients were receiving ACE-I and/ or diuretics with CCB and BB being lesser commonly used. These findings indicate that medication use was mostly consistent with JNC 7th report recommendation among diabetic hypertensive patients. However, there is still room for improvement with regard of combination therapy and better BP control. We expected that patients with IHD will be using more CCB and/ or BB than patients without IHD. However, there was no significant difference in the use of CCB and BB in the groups and that ACE-I and/ or diuretics were the most commonly used as mono or combination therapy in both groups. The rationale for investigating the antihypertensive use based on the presence of IHD is that many patients with diabetes mellitus have IHD for which BB and CCB are preferred choices by JNC 7th report.

ACE-I was the most commonly prescribed drug class both in mono and combination therapy. The use of ACE-I among diabetic hypertensive patients is in accordance with the JNC recommendations for the management of hypertension among diabetic hypertensive patients. The reported mono and combination use of ACE-I was 43.3% which is closer to that reported from Bahrain but less than that reported from USA in treating diabetic hypertensive patients.15,16 The results obtained in the current study were different from those reported in a study carried out five years ago in Palestine.17 In the current study, there was an overall increase in the use of ACE-I compared to that reported five years ago.17

In a previous study carried out on patients with diabetes and hypertension, the reported prevalence of cough associated with the use of ACE-I was 14.9%, with 4.7% of patients interrupting treatment as a result.18 Similarly, the UKPDS Group noted that 4% of patients receiving captopril discontinued therapy due to cough. These reported adverse effects of ACE-I could partially explain the underutilization of ACE-I reported in the current study. ARBs are considered appropriate agents if patients cannot tolerate an ACE-I.4 However, the use of ARBs were rarely prescribed in the current study.

Diuretics ranked second when considering overall utilization of antihypertensive drugs and second when considering antihypertensive monotherapy. Combination of ACE-I with diuretic was the most commonly prescribed. This combination is pharmacologically favorable since it produces an additive antihypertensive effect and minimizes most adverse effects of either the ACE-I or the diuretics especially hypokalemia.19 The importance of the diuretic agent was emphasized by the “Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to prevent Heart Attack Trial” ALLHAT study.20 Calcium channel blockers (CCB) ranked third in monotherapy and ranked third in overall antihypertensive drug utilization. The non dihydropyridine, diltiazem, was the most commonly prescribed CCB and verapamil being the least commonly prescribed. The dihydrpiridine, nifedipine and amlodipine, were in between. The popularity of the non-DHP diltiazem may be due to its reported positive effects on diabetic proteinuria.21 ACE-I plus CCB combination was not very common, although it could provide synergistic antihypertensive and renoprotective activity, but their effects on proteinuria is comparable to ACE-I alone.22 Non-DHP (e.g. diltiazem) plus ACE-I combination has been reported to lower insulin resistance and has an additive anti-proteinuric effect.21

Similar studies conducted by a research group in Bahrain on patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension showed that the prescribing of antihypertensive medications differ in many instances from the world health organization guidelines especially regarding the choices and drug combinations of antihypertensive drugs and that the appropriateness of anti-diabetic drug choice is questionable in relation to the antihypertensive drug used.23 A second study carried out in Bahrain by the same group mentioned above compared family physicians’ and general practitioners’ approaches to drug management of diabetic hypertension.15 In this study, the authors carried out a retrospective prescription-based study on 1266 diabetic hypertensive patients. The authors concluded that there are substantial differences between Family physicians and general practitioners in terms of preference for different drug classes for the management of diabetic hypertension and that there was suboptimal compliance among both FP and GP to international recommendations. Finally, it is interesting to note that the extent of BP control achieved in groups treated with mono-therapy or combination therapy did not differ significantly. Similar findings were obtained by Sequeira and co-workers and Westheim and co-workers.24,25 Potential explanation for the high proportions of poor BP control could be the lack of drug compliance among diabetic patients as a result of adverse events of the antihypertensive medications.

From the current study, we recommend (1) better drug education for health care providers regarding appropriate and international guidelines for diabetic hypertensive patients, and (2) better follow up for their BP control. This could be achieved through clinical pharmacist whose responsibility is to deliver continuing medical education in the field of current pharmacotherapy.

CONCLUSIONS

We concluded from this study that there was a suboptimum use of combination therapy among diabetic hypertensive patients in general. Furthermore, the majority of patients were not on target blood pressure. Patterns of antihypertensive therapy were generally but not adequately consistent with international guidelines. Areas of improvement include increasing ACE-I drug combinations, decreasing the number of untreated patients, and increasing the proportion of patients with controlled blood pressure in this population.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest. No funding was available for this project.

Contributor Information

Waleed M. Sweileh, College of Pharmacy, Clinical Pharmacy Graduate Program. An-Najah National University, Nablus (Palestine)

Ansam F. Sawalha, College of Pharmacy, Clinical Pharmacy Graduate Program, and Poison Control and Drug Information Center (PCDIC). An-Najah National University, Nablus (Palestine)

Sa’ed H. Zyoud, Poison Control and Drug Information Center (PCDIC). An-Najah National University. Nablus (Palestine)

Samah W. Al-Jabi, College of Pharmacy, Clinical Pharmacy Graduate Program. An-Najah National University, Nablus (Palestine)

Eman J. Tameem, Poison Control and Drug Information Center (PCDIC). An-Najah National University. Nablus (Palestine)

Nasr Y. Shraim, College of Pharmacy, Clinical Pharmacy Graduate Program. An-Najah National University, Nablus (Palestine)

References

- 1.Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics Detailed Statistics. Health survey 2000. Percentage of Persons Who Indicated Having Certain Chronic Diseases and Receiving Treatment by Disease and Selected Background Characteristics. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simonson DC. Etiology and Prevalence of hypertension in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1988;11(10):821–827. doi: 10.2337/diacare.11.10.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grundy SM, Benjamin IJ, Burke GL, Chait A, Eckel RH, Howard BV, Mitch W, Smith SC, Jr, Sowers JR. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 1999;100(10):1134–1146. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylurea or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus (UKPDS 33). UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Lancet. 1998;352(9131):837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein M, Sowers JR. Diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Hypertension. 1992;19(5):403–418. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.5.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stamler J, Vaccaro O, Neaton JD, Wentworth D. Diabetes, other risk factors, and 12-yr cardiovascular mortality for men screened in the multiple risk factor intervention trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(2):434–444. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hypertension in Diabetes Study (HDS):I. Prevalence of hypertension in newly presenting type 2 diabetic patients and the association with risk factors for cardiovascular and diabetic complications. J Hypertens. 1993;11(3):309–317. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199303000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlöf B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, Ménard J, Rahn KH, Wedel H, Westerling S. Effects of intensive blood pressure lowering and low dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principle results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomized trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755–1762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of antioxidant vitamin supplementation in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9326):23–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09328-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chin MH, Su AW, Jin L, Nerney MP. Variations in the care of elderly persons with diabetes among endocrinologists, general internists, and geriatricians. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(10):M601–606. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.10.m601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris MI. Health care and health status and outcomes for patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(6):754–758. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martin TL, Selby JV, Zhang D. Physician and patient prevention practices in NIDDM in a large urban managed-care organization. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(8):1124–1132. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.8.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuomilehto J, Rastenyte D, Birkenhäger WH, Thijs L, Antikainen R, Bulpitt CJ, Fletcher AE, Forette F, Goldhaber A, Palatini P, Sarti C, Fagard R. Effects of calcium-channel blockade in older patients with diabetes and systolic hypertension. Systolic hypertension in Europe trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):677–684. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ. Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al Khaja KA, Sequeira RP, Mathur VS, Damanhori AH, Abdul Wahab AW. Family physicians’ and general practitioners’ approaches to drug management of diabetic hypertension in primary care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2002;8(1):19–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2002.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooke CE, Fatodu H. Physician conformity and patient adherence to ACE inhibitors and ARBs in patients with diabetes, with and without renal disease and hypertension, in a medicaid managed care organization. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12(8):649–655. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2006.12.8.649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waleed M, Sweileh, Ola A, Aker, Nidal A. Jaradat. Pharmacological and Therapeutic analysis of anti-diabetic and antihypertensive drugs among diabetic hypertensive patients in Palestine. Journal of the Islamic University of Gaza, (Natural Sciences Series) 2004;12(2):35–57. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malini PL, Strocchi E, Fiumi N, Ambrosioni E, Ciavarella A. ACE inhibitor-induced cough in hypertensive type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(9):1586–1587. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishimitsu T, Yagi S, Ebihara A, Doi Y, Domae A, Shibata A. Long term evaluation of combined antihypertensive therapy with lisinopril and a thiazide diuretic in patients with essential hypertension. Japan Heart J. 1997;38(6):831–840. doi: 10.1536/ihj.38.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid- Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid- Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT) JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981–2997. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bakris GL, Weir MR, DeQuattro V, McMohan FG. Effects of an ACE inhibitor/calcium antagonist combination on proteinuria in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1998;54(4):1283–1289. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Velussi M, Brocco E, Frigato F, Zolli M, Muollo B, Maioli M, Carraro A, Tonolo G, Fresu P, Cernigoi AM, Fioretto P, Nosadini R. Effects of cilazapril and amlodipine on kidney function in hypertensive NIDDM patients. Diabetes. 1996;45(2):216–222. doi: 10.2337/diab.45.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalid AJ, Khaja Al, Reginald P, Sequeira, Vijay S Mathur. Prescribing pattern and therapeutic implications for diabetic hypertension in Bahrain. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35(11):1350–1359. doi: 10.1345/aph.10399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sequeira RP, Al Khaja KA, Damanhori AH. Evaluating the treatment of hypertension in diabetes mellitus: a need for better control? J Eval Clin Pract. 2004;10(1):107–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2003.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westheim A, Klemetsrud T, Tretli S, Stokke HP, Olsen H. Blood pressure levels in treated hypertensive patients in general practice in Norway. Blood Press. 2001;10(1):37–42. doi: 10.1080/080370501750183372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]