Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a major depressive episode that occurs four weeks after delivery. Its risk increases during the first ninety days after delivery and continues for almost two years. The aim of present study is to assess the prevalence of PPD and the associated risk factors in the Eastern Province capital of Saudi Arabia.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted in the five largest Primary Healthcare Centers of Dammam. Four hundred and fifty mothers – visiting the health centers for immunizing their children at age two to six months – were selected by proportionate allocation to the population served by each health center. The mothers were screened for PPD using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and interviewed for the associated risk factors.

Results:

It was found that 17.8% of the women had PPD. Regression analysis revealed that the strongest predictor of PPD was a family history of depression, followed by non-supportive husband, lifetime history of depression, unwanted pregnancy, and stressful life events. It was recommended to screen all high-risk mothers for PPD, while visiting the Primary Care Well-Baby Clinics.

Keywords: Postpartum depression, prevalence, risk factors, Saudi Arabia

Introduction

Giving birth to a new baby is usually a pleasurable and satisfactory experience; but some mothers experience some emotional difficulties. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders, fourth edition defined Postpartum Depression (PPD) as a major depressive episode that occurs within four weeks after delivery.[1] Its risk increases during the first ninety days after delivery and continues for almost two years.[2] Physicians should distinguish PPD from baby blues, which are characterized by mild depressive symptoms. The blues typically peak four to five days after delivery, may last hours to days and resolve by the tenth postnatal day.[1]

A meta-analysis, including 59 studies from North America, Europe, Australia, and Japan estimated the prevalence of postpartum depression as 13%.[3] Arab women showed higher rates, such as 22% in the United Arab Emirates and 21% in Lebanon.[4,5] The prevalence of depression is similar for postpartum and non-pregnant women, but the onset of new episodes of depression is higher in the first five weeks in postpartum than in the non-pregnant controls.[6]

The exact cause of PPD is unknown; however, some psychosocial and obstetric factors might increase the risk of developing postpartum depression. Lack of social support and marital conflicts;[3,7,8,9] prior history of depression or other emotional problems and family psychiatric history;[10,11,12] obstetric and infant problems, like previous miscarriage, lack of breastfeeding, and congenitally malformed infants,[13,14] in addition stressful life events were reported as risk factors.[15] Some studies have found that unemployment, low level of education, and unwanted pregnancy are associated with increased risk of developing PPD.[10,14,16]

Postpartum depression is a significant and common health problem that causes a considerable amount of impact and distress on the family and society. PPD occurs at a period when infant development and learning are happening; causing children whose mothers have PPD to have behavioral, cognitive, and emotional problems.[17]

The Saudi population is a relatively growing one; as indicated by a total fertility rate of 2.8 per woman and an annual population growth rate of 2.4%.[18] In spite of that, postnatal care is only concerned with obstetric problems and baby's health, while the social and psychological well-being of the mother is neglected or rarely considered.

Therefore, the aim of present study is to assess the magnitude of postpartum depression in the Eastern Province Capital of Saudi Arabia, by estimating its prevalence and associated risk factors.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted in the Primary Health Care (PHC) centers of Dammam city, the capital of the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Five out of 22 Health Centers were included in the study; where centers with the largest population were selected. The study sample was calculated by Epi Info at an expected frequency of 17 ± 4%[3,4,5] and 95% confidence level. It was found that the minimum required sample size was 339. Accordingly, 450 mothers were selected from the different health centers, by proportionate allocation to the population served by each health center. All mothers, willing to participate in the study and coming for immunizing their two- to six-months-old children were included in the study, till the proportionate sample was obtained.

The mothers were interviewed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). It is a 10 item self-report questionnaire designed specifically for detection of depression in the postpartum period.[19] It has been validated and translated into more than 12 languages, including Arabic.[20] Responses were scored 0-3 indicating the severity of manifestations, with a maximum score of 30. The cut-off point of 12/13 has shown a sensitivity of 68 to 95% and specificity of 78 to 96%; and the cut-off point of 9/10 demonstrated a sensitivity of 84 to 100% and a specificity of 82 to 88%.[21] Therefore, in the present study Postpartum Depression was categorized into moderate (score 10-12) and severe (score 13 or more).

In addition, an interview questionnaire was developed covering the socio-demographic information and risk factors for PPD, for example, obstetric history, personal and family history of depression, stressful life events, and social support.

A pilot study was conducted in one Primary Health Care (PHC) center in Dammam city. The aim of research study was explained to all the participants and their consent was taken after assuring them about the confidentiality of the collected information.

All collected data was entered into SPSS version 16 for statistical analysis. The total depression score was calculated by summation of the individual question scores. Univariate descriptive analysis of the socio-demographic characteristics of the study sample and bivariate analysis, using the X2 test for qualitative analysis, were conducted. Fischer's exact P was considered if more than 20% of the cells had an expected frequency of less than 5. Stepwise logistic regression analysis was also done to determine the predictors of PPD. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

The present study included 450 mothers. Their mean age was 27.8 ± 5.4 years.

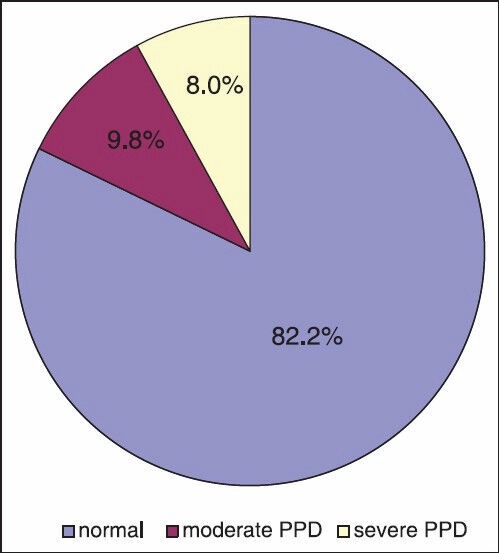

Figure 1 illustrates the prevalence of PPD. It was found that 17.8% had PPD, where 9.8% of the mothers had moderate depression and 8% had severe depression.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Postpartum Depression in Dammam

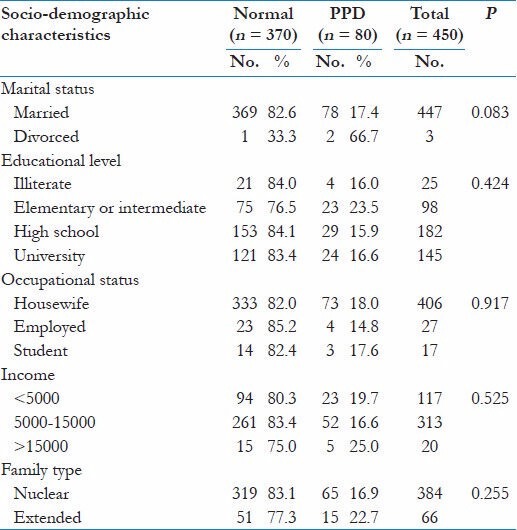

Table 1 shows the association between PPD and the socio-demographic characteristics of the study sample. About 99% of the mothers were married and the rest were divorced. About 40% had completed high school and 32% had completed university education, while the rest had an intermediate level of education or below. The majority were housewives (90%), living in nuclear families (85%). About two-thirds came from middle income families (70%), about 26% from low income, and the rest from high income families. No significant relationship between PPD and marital status, educational level, occupational status, income or family type, was detected.

Table 1.

Association between postpartum depression and the socio-demographic characteristics

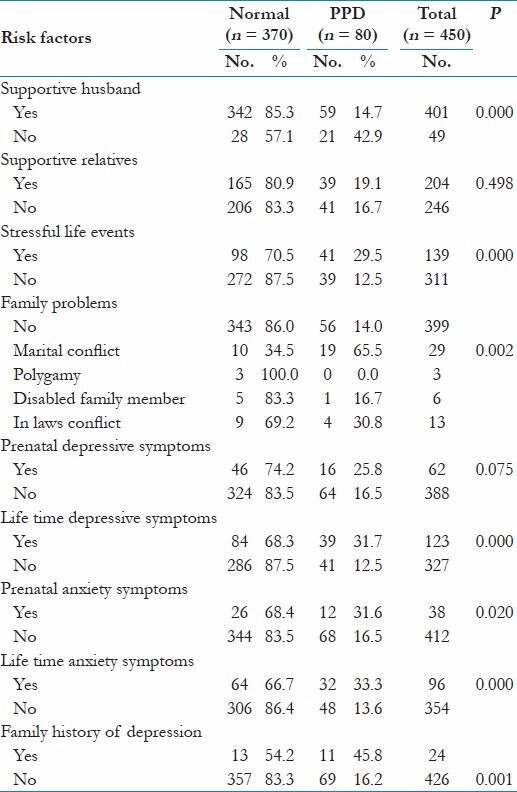

Table 2 shows the association between postpartum depression and psychosocial risk factors. With regard to social support, about 89% of the studied mothers reported having a supportive husband and 45.3% mentioned supportive relatives. It was noticed that the most common risk factor was stressful life events (30.9%), followed by a lifetime history of depression (27.3%), a lifetime history of anxiety (21.3%), prenatal depression (13.8%), family problems (11.3%), prenatal anxiety (8.4%), and a family history of depression (5.3%). Unsupportive husband, family problems, stressful life events, lifetime history of depressive or anxiety symptoms, prenatal anxiety and family history of depression were significantly associated with PPD. However, no association between PPD and supportive relatives was detected.

Table 2.

Association between postpartum depression and psycho-social risk factors

Table 3 demonstrates the relationship between PPD and maternal and child risk factors. It was found that unwanted pregnancy and poor health condition of the infant were significantly associated with PPD; their occurrence was 32.7 and 14%respectively. However, the presence of maternal chronic disease, health condition of the mother during pregnancy, mode of delivery, delivery experience, and postpartum duration had no relation to PPD.

Table 3.

Association between postpartum depression and maternal and child risk factors

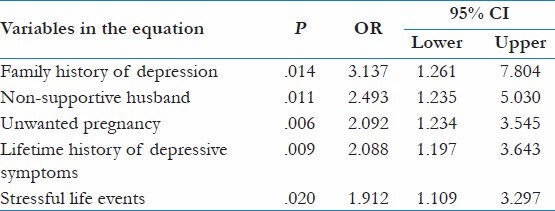

Table 4 demonstrates the results of a stepwise logistic regression model. The socio-demographic characteristics, psychosocial, maternal, and child risk factors were entered in the model. It was found that the strongest predictor of PPD was a family history of depression (OR = 3.1), followed by a non-supportive husband (OR = 2.5), unwanted pregnancy (OR = 2.1), lifetime history of depressive symptoms (OR = 2.1), and stressful life events (OR = 1.9).

Table 4.

Predictors of postpartum depression in Dammam

Discussion

The present study revealed that the prevalence of Postpartum Depression was 17.8%, where 8% had severe depression. The rate was higher than the prevalence estimated by a meta-analysis that included studies from North America, Europe, Australia, and Japan.[3]

An association between PPD and various socioeconomic characteristics like a low level of education, unemployment, and low socioeconomic status has been reported by some studies.[10,14,16] However, this association has not been detected in the present study, as women in our society are usually financially supported by their spouses or relatives, so unemployment would not place extra stress on the mothers.

Postpartum depression can interfere with maternal – infant bonding, thereby, adversely influencing infant development and contributing to the mother's sense of shame and guilt. The negative interaction patterns formed during the early critical bonding period may impact on later child development, despite recovery from PPD. However, maternal remission can have a positive effect on the offsprings.[22]

Therefore, early detection and management of the disorder should be given priority during postnatal care, especially for mothers at risk. According to the present study the predictors of PPD were a family history of depression, non-supportive husband, unwanted pregnancy, lifetime history of depression, and stressful life events. Primary care well baby visits are opportune times to screen for PPD, because they provide frequent contact between the mother and health care providers in the first two years postpartum.

In Saudi Arabia, Eastern Province a mental health program has been introduced into Primary Care, in 2003. Two community mental health centers have been established in the province. These centers provide complementary services, such as psychosocial rehabilitation that cannot be provided in the primary care centers. They receive patients from all primary care centers in the catchment area.[23]

Psychotropic medication is common for treatment of postpartum depression. However, there is concern on the part of both patients and healthcare providers regarding the implications of psychotropic medication for breastfeeding women and their infants.[24] Several types of psychotherapy have been found to be effective for the treatment of postpartum depression like: Individual interpersonal psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and group or family therapy.[25]

Group or family therapy would be the most appropriate type of psychotherapy that can be provided for PPD patients in the community mental health centers, as unsupportive husband, family problems, stressful life events, and unwanted pregnancy were all significantly associated with the PPD in the current study. Strain in the marital relationship is both a risk factor for and consequence of PPD.[22] Also, a significant number of fathers become depressed postpartum, further exacerbating the effects of PPD on the mother, marriage, and child development.[26]

Social support is a multidimensional concept; sources of support can be spouse, relatives and friends. Receiving social support during stressful times is thought to be a protective factor against developing depression.[3,7,8,9] About 85% of the mothers in the present study lived in nuclear families, 89% reported having a supportive husband and 45% having supportive relatives. It was found that a supportive husband had a significant role in protection against PPD, compared to supportive relatives, emphasizing again the role of family therapy for management of PPD in our society.

In conclusion, postpartum depression is a common mental health problem in the Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia. Therefore, it is recommended to screen high-risk mothers for PPD during primary care well-baby visits and to refer the detected cases to the community mental health centers for early management and prevention of psychosocial impairment of the family.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Diagnostic and statstical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris B. Postpartum depression. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:405–16. [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression: A meta analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry. 1996;8:37–54. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green K, Broome H, Mirabella J. Postnatal depression among mothers in the United Arab Emirates: Socio-cultural and physical factors. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11:425–31. doi: 10.1080/13548500600678164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaaya M, Campbell OM, El Kak F, Shaar D, Harb H, Kaddour A. Postpartum depression: Prevalence and determinants in Lebanon. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2002;5:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s00737-002-0140-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Pedersen CB, Mors O, Mortensen PB. New parents and mental disorders: A population-based register study. JAMA. 2006;296:2582–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brugha TS, Sharp HM, Cooper SA, Weisender C, Britto D, Shinkwin R, Sherrif T, et al. The Leicester 500 Project. Social support and the development of postnatal depressive symptoms, a prospective cohort survey. Psychol Med. 1998;28:63–79. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins NL, Dunkel-Schetter C, Lobel M, Scrimshaw SC. Social support in pregnancy: Psychosocial correlates of birth outcomes and postpartum depression. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:1243–58. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.6.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inandi T, Elci OC, Ozturk A, Egri M, Polat A, Sahin TK. Risk factors for depression in postnatal first year, in eastern Turkey. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1201–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.6.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kheirabadi GR, Maracy MR, Barekatain M, Salehi M, Sadri GH, Kelishadi M, et al. Risk factors of postpartum depression in rural areas of Isfahan Province, Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12:461–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner M. Postnatal depression: A few simple questions. Fam Pract. 2002;19:469–70. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson LM, Reid AJ, Midmer DK, Biringer A, Carroll JC, Stewart DE. Antenatal psychosocial risk factors associated with adverse postpartum family outcomes. CMAJ. 1996;15(154):785–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck CT. A meta-analysis of the relationship between postpartum depression and infant temperament. Nurs Res. 1996;45:225–30. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghubash R, Abou-Saleh MT. Postpartum psychiatric illness in Arab culture: Prevalence and psychosocial correlates. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:65–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hickey AR, Boyce PM, Ellwood D, Morris-Yates AD. Early discharge and risk for postnatal depression. Med J Aust. 1997;167:244–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb125047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel V, Rodrigues M, DeSouza N. Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: A study of mothers in Goa, India. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:43–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper PJ, Murray L. Postnatal depression. British Medical Journal. 1998;316:1884–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7148.1884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. Global health observatory data repository. 2010. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 12]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.country.country-SAU .

- 19.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ghubash R, Abou-Saleh MT, Daradkeh TK. The validity of the Arabic Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1997;32:474–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00789142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray L, Carothers AD. The validation of the Edinburgh Post-natal depression scale on a community sample. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:288–90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.157.2.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Talati A, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, et al. Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: A STARFNx01D-child report. JAMA. 2006;295:1389–98. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saudi Ministry of Health. Integrated primary care for mental health in the Eastern Province. 2010. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 13]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/services/SaudiArabia.pdf .

- 24.Wisner KL, Zarin DA, Holmboe ES, Appelbaum PS, Gelenberg AJ, Leonard HL, et al. Risk-benefit decision making for treatment of depression during pregnancy. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1933–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.12.1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O'Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Wenzel A. Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:1039–45. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paulson JF, Bazemore SD. Prenatal and postpartum depression in fathers and its association with maternal depression. JAMA. 2010;303:1961–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]