Abstract

Aim:

To determine the prevalence of H. pylori based on endoscopic biopsy and to investigate the association between H. pylori and endoscopy diagnosis and histopathological diagnosis.

Materials and Methods:

Over a period of two years, 228 endoscopic biopsies were included. Endoscopy diagnosis, histopathological diagnosis, and colonization with H. pylori were recorded and compared using appropriate statistical tests.

Results:

The overall prevalence of H. pylori was 68%; 69.6% in males and 66.7% in females. Duodenal and gastric ulcers were seen more in males (63.2% and 60%) compared with females (32.1% and 40%) (P < 0.001). The total rate of colonization of H. pylori in duodenal ulcer and gastric ulcer (85.7% and 84%, respectively) was significantly higher than those in gastritis, duodenitis, and gastric cancer (61.8%, 69.2%, and 60%, respectively) (P = 0.046). Histologically, chronic active gastritis and chronic follicular gastritis was significantly higher in duodenal ulcer and gastric ulcer (57.1%, 44% and 21%, 40%) in comparison to chronic persistent gastritis (21.4%, 16%) with P value < 0.001. Similarly, chronic active gastritis and chronic follicular gastritis had higher prevalence of H. pylori infection in comparison to chronic persistent gastritis (85.3%, 83.3% vs. 41.4%) with P value < 0.001.

Conclusion:

This study reveals that the overall prevalence of H. pylori infection is high in our setting with no significant difference in gender. Peptic ulcers were common in males. Those with peptic ulcers had higher rates of H. pylori colonization. Chronic active gastritis and chronic follicular gastritis were common histological findings in ulcerative diseases with significantly higher H. pylori positivity.

Keywords: Duodenal ulcer, gastritis, gastric ulcer, Helicobacter pylori, peptic ulcer disease, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy Key Messages: This study revealed that the overall prevalence of H. pylori infection is very high with higher rates in ulcerative diseases and those with chronic active gastritis and chronic follicular gastritis. The high prevalence of the H. pylori reflects that it is a major public health burden; therefore, proper strategies of control and eradication should be implemented.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is of major concern today because of its causal relationship with gastro duodenal disease. One half of the world's population has H. pylori infection, with an estimated prevalence of more than 90% in developing countries.[1,2,3,4,5] In our country, the reported prevalence of H. pylori ranged from 30% to 67%.[6,7,8,9,10] It is proven that H. pylori is the principal cause of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease as well as gastric cancer.[11,12,13,14,15]

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of H. pylori based on histology and to assess its relationship with endoscopy diagnosis and histological diagnosis.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted at this hospital over a period of two years from April 2011-March 2013. Data analysis was done from all consecutive individuals referred from outpatient as well as inpatient department who had undergone gastric biopsy during upper GI endoscopy for various dyspeptic symptoms like pain abdomen, nausea, vomiting, belching, throat pain, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, weight loss etc. Those with chronic liver disease with esophageal varices, chronic kidney disease, and age <14 years were excluded from the study.

The endoscopic diagnosis was categorized into gastritis, duodenitis, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, and neoplasm. Gastritis has been classified in several ways, which differ from institution to another, from one department to another depending upon the examiner. Therefore, all kinds of gastritis were combined into one. If two or more diagnosis were present in a patient, the severest form of disease was recorded.

The biopsy specimens were usually taken from the antrum and other location if required and sent for histological examination. The biopsy specimens were fixed overnight in 10% buffered formalin, processed, embedded in paraffin, and cut and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (HandE) and Giemsa stain. There are no other modalities available for diagnosis of H. pylori in our institution. Histological reporting was done for diagnosis of gastric mucosa inflammation, atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, neoplasia, and H. pylori colonization. Histologically, gastritis was classified into chronic active gastritis (CAG), chronic follicular gastritis (CFG), and chronic persistent gastritis (CPG) according to the Sydney system.[16]

Informed consent was taken from the patient/patient party. Identity of the patients was not disclosed. The study was approved by the hospital ethical review committee.

Descriptive and frequency analysis of the data from the study was expressed as counts, percentage, and means or medians as appropriate to provide the overall picture. The data were analyzed using Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 14 for windows. Chi-square test with exact test was used where applicable. P values of < 0.05 were considered to denote statistical significance.

Results

During the study period of two years, 980 diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopies were performed for a range of indications, of which 332 biopsies were taken. Among 332 patients, 104 patients were excluded for various reasons, leaving 228 for the study. The age of the patients ranged from 16-87 (mean of 44.7 ± 15.8). Among all the patients, 126 (55.3%) were females and 102 (44.7%) were males.

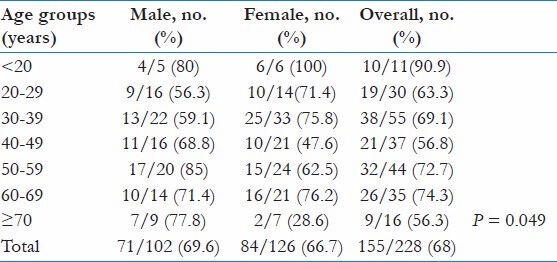

The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection was 68% (n = 155/228). The distribution of colonization in <20 years, 20-29 years, 30-39 years, 40-49 years, 50-59 years, 60-69 years, and > 70 years age groups was 90.9%, 63.3%, 69.1%, 56.8%, 72.7%, 74.3%, and 56.3%, respectively. The prevalence of H. pylori was highest in the <20 age group (90.9%) and lowest among ≥70 age group (56.3%); however, the difference was not statistically significant [Table 1]. Similarly, the overall prevalence among male and female counterpart was similar (69.6% and 66.7%, respectively). However, rate of H. pylori infection was significantly higher among males in comparison to females in >70 age group (P = 0.049).

Table 1.

Prevalence of H. pylori among different age and gender groups

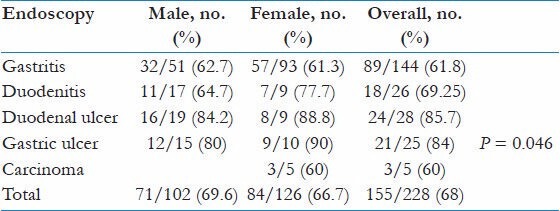

Endoscopy finding was divided into gastritis, duodenitis, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, and gastric cancer, which was diagnosed in 144 (63.2%), 26 (11.4%), 28 (12.3%), 25 (11%), and 5 (2.2%) patients, respectively. It was noted that duodenal ulcer and gastric ulcer were seen significantly more common among males than females (n = 19 (67.9%) vs. n = 9 (32.1%) and n = 15 (60%) vs. n = 10 (40%), respectively, P < 0.001); in contrast, gastritis was more common among females n = 93 (64.6%) vs. n = 51 (35.4%) among male counterparts.

The colonization rate of H. pylori in relation to different endoscopy diagnosis is illustrated in Table 2. The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection in gastritis was 89 (61.8%), in duodenitis 18 (69.2%), in duodenal ulcer 24 (85.7%), in gastric ulcer 21 (84%), and in gastric Ca 3 (60%). Those with ulcerative lesion had significantly higher prevalence of H. pylori (P = 0.046); however, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of H. pylori between gastritis, duodenitis, and gastric carcinoma.

Table 2.

Prevalence of H. pylori in relation to endoscopy diagnosis

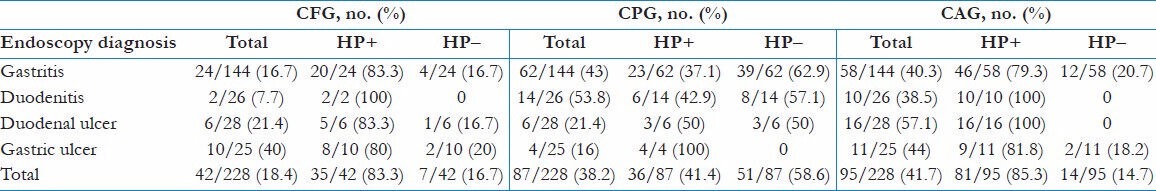

Rates of histological features and H. Pylori infection in relation to endoscopy diagnosis are shown in Table 3. The histological features were divided into CAG, CPG, and CFG, which were detected in 95 (41.7%), 87 (38.2%), and 42 (18.4%) of cases respectively. CAG was the frequent finding in those who had duodenal ulcer (n = 16; 57.1%), all of which (100%) were colonized with H. pylori followed by gastric ulcer (n = 11; 44%). CFG was most common in gastric ulcer (n = 10; 40%), whereas CPG was common in non-ulcerative disease (duodenitis - n = 14; 53.8%; gastritis - n = 62; 43%). CAG and CFG were more common in ulcerative diseases, whereas CPG was more common in gastritis and duodenitis (P < 0.001). Those who had histological features of CAG had highest prevalence of H. pylori (n = 81; 85.3%), followed by CFG (n = 35; 83.3%) and CPG (n = 35; 41.4%) with P value < 0.001.

Table 3.

H. pylori infection and histological features in relation to endoscopy diagnosis

Intestinal metaplasia was identified in 5% (11/228) of the sample, amongst which 6 (55%) had H. pylori positivity. The mean age of the patient with intestinal metaplasia was 55.7 ± 11.9 (range = 32-71), of which 5 were females and 6 were males. All the diagnosed 5 gastric cancer cases were females, of which 3 (60%) were H. pylori-positive.

Discussion

Since H. pylori was first discovered by Warren and Marshall in 1983, it has radically changed our understanding and clinical management of gastroduodenal disease, and much has been researched about its clinical aspects and its epidemiology.[17] Its incidence and prevalence differs in relation to different factors like geography, ethnicity, age, and socio-economic factors — high in developing countries and lower in the developed world.[2,3] Overall, researchers found a consistent pattern in most developing nations, where 70 to 90% of adults harbored the bacteria; most individuals acquired the infection as children, before age ten.[4,5] Nepalese data show that the prevalence of H. pylori infection varies widely from 30-67%.[6,7,8,9,10] The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection in our study was 68% (155/228) among symptomatic patients referred for endoscopies in our local setting. This is at the highest end of the range earlier reported in our country. The high prevalence was possibly because the study was done amongst only symptomatic patients.

The prevalence of active H. pylori infection was highest in the youngest group of <20 years (90.9%), which probably reflects the acquisition of the infection during childhood. In terms of age, our data did not coincide with most published studies conducted previously, in which prevalence is seen to rise until it peaks in middle-aged individuals, around 50-60 years. No significant difference was found in the prevalence of infection by gender, except in ≥70 year group. Some studies has shown male predominance in infection,[18,19,20] whereas others have not found any gender difference as in our study.[10,21]

Many patients still attribute symptoms of dyspepsia to diet, stress, and lifestyle factors; however, it is now proven that H. pylori is the principal cause of chronic gastritis and is strongly associated with peptic ulcer disease as well as gastric cancer, including gastric lymphoma (MALT type).[11] Prevalence of ulcerative disease in our study was 23.3% (53/228) and was significantly higher in males. The colonization rate by H. pylori was 85.7% (24/28) and 84% (21/25) in case of duodenal ulcer and gastric ulcer, respectively. A review article reported a colonization rate of H. pylori of 93% for patients with duodenal ulcer and 80% for those with gastric ulcer.[22] Zhang C also found the colonization rate of 80.0% by H. pylori in cases of gastric ulcer, which was similar to our study.[23] Lower H. pylori positivity in duodenal ulcers in our study can be due to prior treatment with proton pump inhibitors as those cases were not excluded. Moreover, the biopsy included tissue mostly from the antral mucosa only. It is suggested that four specimens (two antral, two corpus) should be sent for higher occurrence of the H. pylori positivity. For yielding positive rates after treatment, corpus biopsy is reported particularly helpful.[24] Logan et al. showed that potent acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors resulted in a proximal shift of H. pylori from antrum to corpus in stomach.[25]

According to the histological features, CAG was the most common finding followed by CPG and CFG (41.7%, 38.2%, and 18.4%, respectively). Rate of colonization with H. pylori was significantly higher in CAG and CFG in comparison to CPG (85.3%, 83.3% vs. 41.4%). In CFG, the H. pylori positivity should have been 100% as it has been proven that lymphoid aggregates with germinal centers are characteristic of chronic H. pylori gastritis.[22] Again, this discrepancy is perhaps due to prior intake of proton pump inhibitors who were not excluded from the study, and absence of biopsy sample from corpus.

It is stated that the relative risk of developing gastric carcinoma is 3-6 folds greater in association with H. pylori infection versus control.[13,14] The evidence supportive of an etiological association between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer was sufficient for a Working Group of the International Agency for Research on Cancer to classify such infection as a definite cause of cancer.[15] Interestingly, in our study, all the cases of carcinoma stomach (n = 5) were detected only in females and H. pylori activity was noticed in 3 out of them (60%). Intestinal metaplasia was detected in 5% of the total sample (n = 11), 55% of which were colonized with H. pylori. However, the numbers were too small to comment on. Intestinal metaplasia and the pre-malignant lesion could be detected more if a biopsy from incisura angularis was included. Reports have suggested that maximum degrees of atrophic changes and intestinal metaplasia are consistently identified in this region.[26] The study done by Zhang C showed tight link between H. pylori infection and progression of the gastric pre-cancerous lesions, glandular atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia in various gastric lesion.[19] Further studies need to be done in this regards as it is suggested that the development of gastric cancer spans over decade sequentially starting with the acquisition of H. pylori infection and the development of chronic active gastritis.[27]

There are several limitations with our study. Firstly, our data sheet did not capture data on socio-economic status, education, previous use of drugs like Proton pump inhibitors, NSAID, or anti-platelets. Hence, we were unable to assess the association of these variables with H. pylori prevalence. Secondly, the biopsy sample from stomach was taken from antrum and other sites only if indicated. Therefore, topographic classification of gastritis, as described in the Sydney system, was not possible in this study.

Conclusion

Based on this study, the prevalence of H. pylori detected by histopathology among adult patients with gastrointestinal symptoms was high (68%). Rate of H. pylori infection was higher in youngest age group and lowest among oldest age group with no differences according to gender. Ulcerative lesions were found more common in male, whereas gastritis was common among female patients. The colonization of antrum with H. pylori was very high in ulcerative disease in comparison to non-ulcerative diseases. Histological diagnosis of CFG and CAG was seen commonly in ulcerative disease with higher H. pylori positivity rate in comparison to CPG.

The high prevalence of the H. pylori infection reflects that it is a major public health burden in developing countries like ours and thus an important agenda for public health investigation followed by implementation of proper strategies of control and eradication. Patients presenting for endoscopy for various complaints should routinely have their H. pylori status checked, regardless of indication. The disease has low mortality but has considerable individual suffering and consequently loss of manpower and also cumulative high cost for symptomatic therapy. In-depth further studies need to be done to evaluate the local antibiotic resistance pattern and to assess whether H. pylori infection is strongly related to pre-cancerous lesions like intestinal metaplasia and gastric cancer in this part of world.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof Amita Pradhan for the assistance in statistical analysis, Ms Saroswati for her contribution in data collection and endoscopy and pathology department of KIST Hospital for participating in this study. We would also like to thank KIST Hospital for granting the permission to conduct the study and for the moral and technical support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: KIST medical college hospital.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Go MF. Natural history and epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16(Suppl 1):3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.0160s1003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Megraud F. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. In: Rathbone BK, Heatley RV, editors. Helicobacter pylori and gastroduodenal disease. London: Blackwell Scientific Publication; 1993. pp. 107–23. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veldhuyzen van zantel SJ. Do socioeconimicstatus, marital status and occupation influence the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9(Suppl 2):41–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hunt RH, Xiao SD, Megraud F, Leon-Barua R, Bazzoli F, van der Merwe S, et al. Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines; World Gastroenterology Organization. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20:299–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lacy BE, Rosemore J. Helicobacter pylori: Ulcers and more: The beginning of an era. J Nutr. 2001;131:27895–935. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.10.2789S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rai SK, Shah RD, Bhattachan CL, Rai CK, Ishiyama S, Kurokawa M, et al. Helicobacter pylori associated gastroduodenal problem among the Nepalese. Nepal Med Coll J. 2006;8:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makaju R, Tamang MD, Sharma Y, Sharma N, Koju R, Bedi TR, et al. Comparative study on a homemade rapid urease test with gastric biopsy for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Nepal Med Coll J. 2006;8:97–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makaju RK, Tamang MD, Sharma Y, Sharma N, Koju R, Ashraf M. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Dhulikhel Hospital, Kathmandu University Teaching Hospital: A retrospective histopathologic study. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2005;3:355–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khanal S, Rao BS, Sharma Y, Khan GM, Makaju R. Comparative study between two triple therapy regimens on eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Kathmandu Univ J Sci Engg Technol. 2005:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawasaki M, Kawasaki T, Ogaki T, Itoh K, Kobayashi S, Yoshimizu Y, et al. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Nepal: Low prevalence in an isolated rural village. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:47–50. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199801000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aroori S. Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterol Today. 2001;5:131–3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith VC, Genta RM. Role of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in gastric atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and gastric neoplasia. Microsc Res Tech. 2000;48:313–20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(20000315)48:6<313::AID-JEMT1>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sepulveda AR, Graham DY. Role of Helicobacter pylori in gastric carcinogenesis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2002;31:517–35. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(02)00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunt RH. Will eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection influence the risk of gastric cancer? Am J Med. 2004;117(Suppl 5A):865–915. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Agency for research on Cancer. Infection with Helicobacter pylori. IARC monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic. Risks Hum. 1994;61:177–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Price AB. The sydney system. Histological division. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;6:209–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1991.tb01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suk F, Lien G, Yu T, Ho Y. Global trends in Helicobacter pylori research from 1991-2008 analyzed with the Science Citation Index Expanded. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:295–301. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283457af7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chong VH, Lim KC, Rajendran N. Prevalence of active Helicobacter pylori infection among patients referred for endoscopy in Brunei Darussalam. Singapore Med J. 2008;49:42–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang C, Yamada N, Wu YL, Wen M, Matsuhisa T, Matsukura N. Helicobacter pylori infection, glandular atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in superficial gastritis, gastric erosion, erosive gastritis, gastric ulcer and early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:791–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i6.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dhakhwa R, Acharya IL, Shrestha HG, Joshi DM, Lama S, Lakhey M. Histopathologic study of chronic antral gastritis. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2012;10:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malaty HM, El-Kasabany A, Graham DY, Miller CC, Reddy SG, Srinivasan SR, et al. Age at acquisition of Helicobacter pylori infection: A follow-up study from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2002;359:931–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08025-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixon MF. Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulceration: Histopathological aspects. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;6:125–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1991.tb01451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang C, Yamada N, Wu YL, Wen M, Matsuhisa T, Matsukura N. Comparison of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric mucosal histological features of gastric ulcer patients with chronic gastritis patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:976–81. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i7.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan WY, Hui PK, Leung KM. Coccoid forms of Helicobacter pylori in human stomach. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:503–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/102.4.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Logan RP, Walker MM, Misiewicz JJ, Gummett PA, Karim QN, Baron JH. Changes in the intragastric distribution of Helicobacter pylori during treatment with omeprazole. Gut. 1995;36:12–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stemmermann GN. Intestinal metaplasia of the stomach: A status report. Cancer. 1994;74:556–64. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940715)74:2<556::aid-cncr2820740205>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rozen P. Cancer of the gastrointestinal tract: Early detection or early prevention? Eur J Cancer Prev. 2004;13:71–5. doi: 10.1097/00008469-200402000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]