Abstract

Background:

India is one of the fastest growing economies of the world, and is posed to overtake China in terms of being the most populous nation of the world. The very essential components of primary health care – promotion of food supply, proper nutrition, safe water and basic sanitation and provision for quality health information concerning the prevailing health problems – is largely ignored. Access to healthcare services, provision of essential medicines and scarcity of doctors are other bottlenecks in the primary health care scenario. Complete absence of evidence-based guidelines on clinical scenarios and treatment plans in the primary health care sector, together with overburdening of the secondary and tertiary care sectors, has substantially lowered the quality of care in the nation.

Aim:

To discuss a strategy for a better primary healthcare model.

Methods:

This is a concept paper with an exploratory view of various problems and a suggested strategy to counter it.

Results:

This concept paper suggests a triad of strategies (technology, accountability and ink-blot strategy) that can be adapted to various problems in the primary healthcare scenario.

Discussion:

The concept paper is a preliminary document on a suggested model that needs to be worked out on a broader basis across all stakeholders with operational definitions, standards of procedure and protocols finalised.

Keywords: Health system, primary health care, universal health coverage

Background

One year after the World Health Assembly stated its “Health for All” goal, the World Health Organization came up with the concept of primary health care at the Alma-Ata Conference, USSR, in 1978. With the broad principles of social equity, national coverage, self reliance and inter-sectoral coordination, and the aim to put the people's health in the people's hand, it was defined as:

“essential health care based on practical, scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology made universally accessible to individuals and families in the community through their full participation and at a cost that the community and the country can afford to maintain at every stage of their development in the spirit of self-reliance and self-determination”.[1]

Primary health care is thus a broad concept within the realms of public health, clinical services and health systems that requires optimal performance from various inter-related sectors acting in tandem to achieve the goal of providing essential health care to all citizens.

Primary Health Care in India

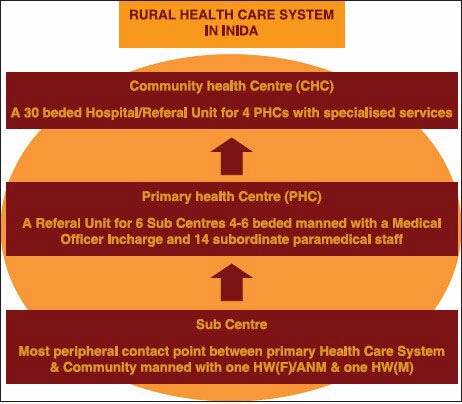

The health care system is India is organized as shown in Chart 1, Primary Health Care System in India.[2] Staffing at all these centers is as per the Indian Public Health Services (IPHS) standards.

Chart 1.

Primary Healthcare System in India

The sub-center is thus the peripheral most and the first contact point between the primary health care system and the community. However, the first contact point between the community and a trained physician is the Primary Health Center, which is supposed to provide an “integrated curative and preventive health care to the rural population with emphasis on preventive and promotive aspects of health care.”[2] However, specialist physicians are available only at the point of Community Health Center, which caters to a population base of 120,000 in the plains and 80,000 in hilly/tribal or difficult areas.

Emerging Challenges in the Primary Health Care Scenario in India

India is one of the fastest growing economies of the world, and is poised to overtake China in terms of being the most populous nation of the world. However, in spite of having a huge population, the government's investment to health in the budget has been only been around 1% of the gross domestic product (GDP).[3] The focus is largely on curative services and quick-fixes, rather than the long-term investment on provision of preventive services, building healthy behavior or quality medical infrastructure. The very essential components of primary health care — promotion of food supply, proper nutrition, safe water and basic sanitation and provision for quality health information concerning the prevailing health problems — is largely ignored. Access to healthcare services, provision of essential medicines and scarcity of doctors are other bottlenecks in the primary health care scenario. Complete absence of evidence-based guidelines on clinical scenarios and treatment plans in the primary health care sector, together with overburdening of the secondary and tertiary care sectors has substantially lowered the quality of care in the nation. A few statistics on these aspects will make the picture clearer:

Healthcare expenditure in India is mainly on curative services, and this is increasing at an alarming rate of 12% per year. Of this, the primary health care segment accounts for more than 60% of the health care delivery market.[4] More than 70% of the health expenditure in India is “out-of-pocket,” meaning that these are unplanned distress expenditures that contribute significantly to the poverty levels.[4] The Indian government plans to roll out universal health coverage across the nation. In spite of all this, the total expenditure on healthcare in the budget, even in the financial years 2013-2014, is less than 2% of the GDP.[5]

Even the Prime Minister of the nation rues the fact that “Against a desirable rate of 1 doctor per 1000 population, we have 1 doctor per 2000 people. Against a norm of 3 nurses per doctor, we have 3 nurses for every 2 doctors.”[6] ; the situation is worse in rural India.

Indians, particularly rural Indians, have to travel hundreds of kilometers to access basic healthcare.[4]

Primary healthcare is a default/"out of compulsion" career choice as more than 95% of young doctors want to pursue speciality training.[5]

Three out of four doctors responsible for care of children in hospitals in seven less-developed countries reported inadequate knowledge in managing common childhood illnesses such as childhood pneumonia, severe malnutrition and sepsis.[7]

Technology

Primary healthcare is largely seen by policy makers, and even by most doctors, as a cheap, low-technology, nonprofessional care for the rural poor and dealing with only few common diseases. Hence, adequate resources are not assigned and investment is minimal. Some of the major lacking aspects in the primary health care set up as discussed earlier can be sorted out if India concentrates and merges its healthcare industry to the sector for which India is renowned worldwide — information and technology. “Naysayers might argue about the high costs involved with initially setting up the telemedicine network but they overlook the fact that in the long run it actually does bring down the health overheads. (cost of travel, number of workdays lost, the costs and harassment associated, special incentives to be given to specialist doctors for serving in the rural area etc.).”[8]

With increasing access to online information and services, it is only normal for even rural citizens to expect that the health sector will provide them with similar access, efficiencies and ease of information and connection as in other sectors and in urban areas. Citizens not satisfied with the quality of care at the first level of contact bypass one or two levels in the health system and seek care only in higher systems, leading to overcrowding there and hampering quality of care in higher centers too.

The pressures from the burgeoning but educated middle class in semi-urban and ruralarears on the primary health care set up might be eased by making self-care technologies available. Affordable technology-based diagnostics is another area where efforts must be specifically directed.[9] The Indian pharmaceutical industry, which is one of the prime movers in the generic medicine market, should heavily focus on even more safer, effective and cheaper drugs and vaccines.[9]

With limited health personnel and their unwillingness to move to rural areas, the only viable option seems to be adopting telemedicine where the scarce resource of physician specialists are made more accessible by use of affordable technologies. Electronic information exchange, vide individual electronic health records (IEHRs) (best if linked with the Aadhar Card numbers that give unique IDs to every Indian citizen), will enable a strong support for multi-disciplinary primary health care collaboration and enable efficient exchange of information between the primary health care, community and specialist settings.

“The co-emergence of information technologies accessible to the mass population and user-driven health care provide a potential catalyst or innovation”[10] for transition to a better primary healthcare delivery system. Health care providers vide such technology-enabled primary health care networks will thus be able to set up a virtual, integrated health care team. Supported by on-ground staff, the virtual team will be able to give accurate and timely information to provide evidence-based treatment that can be individualized per the needs of the patient by the ground staff.

Digital patient information will also immensely help by allowing access of primary health care data by researchers and epidemiologists located in world class facilities. They can analyze it and suggest suitable “fixes,” monitor them and even generate guidelines for treatment in a primary healthcare set up, all with the click of a mouse.

Abundant use of appropriate technology can help improve the quality of care too. Technology use will also allow development of the much-required “primary care teams to deliver effective evidence based preventive and chronic care outside hospital.”[10] Telemedicine has already been used in providing home-based dialysis care in (end-stage renal disease [ESRD]) patients of Hyderabad. It has brought down the costs of care to more than 90%.[11] “For a global IT giant like India, which has already made wonders by making the worlds cheapest tablet, Aakash, setting up a cheap yet robust Telemedicine network should not be that difficult.”[8] Such a telemedicine network integrated into the primary healthcare set up will be a major game changer in the health system scenario in India.

Accountability

It is essential to provide and integrate public health services into the primary healthcare set up model. The widely appreciated “Family Health Programme in Brazil” can be adopted easily in India with minor modifications to improve on it. Coupled with appropriate use of technology, it will radically reform the currently rusted primary health care system.

The first point of care should have a primary physician to improve quality of care and patient satisfaction. In order to achieve that, the primary health center is merged together with the community healthcare staff. Here, a multidisciplinary team is made consisting of all staff as entailed in the IPHS together with the addition of the following members in the team — five preventive health workers, one health educator, five health educators, one public health specialist, one manager and one additional doctor per 1000 population (primary care physicians).

Thus, curative, preventive, promotive and public health in the well-defined geographic area is the responsibility of one team. The Multidisciplinary Health Team as mentioned above will man the particular primary healthcare set up for a well-defined geographic area and be accountable and answerable for the “Health for All” in that particular well-defined geographical area. The manager (preferably an MBA) will be responsible for all administrative and liasoning work, together with smoothening the workflow and removing bottlenecks in the system. All logistics should be exclusively his domain. This would leave the doctor and the public health specialist free to work on the skills they are trained for and not be bogged down by administrative work. Additional health educators will free all the other categories of workers from the job of providing health education and information. These health educators together with the preventive health workers will work under the direct supervision of the public health specialist. Additionally, specialists might be inculcated to the team as per the requirement of the particular community. For example, an infectious disease specialist might join the team in a community suffering from spurts of dengue cases every year. Special Sub Health Teams might also be created as per requirements. For example, a community with a high number of cancer patients might have its Palliative Care team that would provide home-based palliative facilities.

Monitoring will be performed regularly by the team itself and periodically by external nongovernmental evaluators. Monitoring will be carried out regularly by the team itself and periodically by external nongovernmental evaluators. Performance-based incentives to the entire health team on an individual as well as a collective basis based on verifiable results and predetermined performance benchmarks should be the norm. These health teams must enjoy “substantial organisational and professional freedom as long as the health outcomes meet national standards” should be granted[12] as the “one size fits all” model currently in vogue in India is besotted with problems. The public satisfaction to the services provided should also be monitored on a regular basis so that the provision of services and quality of care are driven by demand[12] and not on the whims and fancies of policy makers and perceived requirements. Thus, a culture of better services would be created where the health team would be continually called upon to improve and performance-based pay provided to the team for all improvements they make. Virtual health teams consisting of specialists would support the health team 24*7 together with facilities of transport. This is expected to prevent the “refer more, resolve less” approach currently in vogue in primary health centers for fear of litigation and violence. Once unnecessary referrals from health systems are prevented, the quality of care in the entire health system will improve.

Ink-Blot Strategy

The ink-blot strategy is a military maneuver whereby counter-insurgency and reconstruction efforts spread outwards from secured key areas — as an ink spot expands on paper.[13] The strategy is particularly useful where only a small military force is available and the force gradually pushes out expanding its zone of control, eventually joining together with other similar ink spots. The strategy has been used in the Vietnam War and, more recently, in Iraq by the Americans and in Afghanistan by the NATO.

This ink-blot strategy can be used to implement the model proposed above and any variations in the above model. First, one has to identify a place where ideal conditions of adopting such a model exist or where the existing infrastructure of good practice can be easily modified to implement the concept plan. Various variants of the model might be tested vide different ink blots with similar epidemiological characteristics (for better comparison). Once it is known that the desired changes have taken place and the desirable results have been achieved, each multidisciplinary team is given greater resources at its disposal and the ink-blot area is increased thus establishing a larger area of good practice and better primary health services. Over the course of time, all these places would be converted into a suitable ink color, i.e. better teams with good work practices will be established uniformly in the system eliminating the ink-blots of inferior quality.

Discussion

The plan for including “Technology, Accountability, and an Ink Blot Strategy” as outlined in the paper. The three-pronged strategy for primary healthcare would need a revamp of the entire healthcare system together with broad changes in the medical education sector — such that skill- and experience-oriented academic and career progression is assured. Also, the huge initial investment and the reliance on technology will need a massive commitment on the part of the government. However, the suggested triad will help in solving various issues plaguing the current health system. Technology will enable better outreach as well as increased patient satisfaction and drive up compliance too. It will also prevent the need to travel extensively on health grounds and will thus save expenses on account of travelling as well as loss of “workdays.” In the long run, use of self-diagnostics as well as getting treated in the community under care of a primary care physician, but at the same time enabling access to specialist care, will lead to less burdening of secondary and tertiary care units, thereby improving the quality of care there as well. Infusing accountability will also infuse the sense of work culture and provide better services. The ink-blot strategy, wherein a better team gets a larger area (and hence more funds), will provide an incentive for innovation as well as ensure career progression of all team members. This concept paper however only takes a broad view of the state of primary health care in India, together with problems in its health system and the perceived emerging need of quality medical care. The concept paper recognizes and solves the very complex issue of primary healthcare system reforms in India. This is a preliminary document on a suggested model that needs to be worked out on a broader basis across all stakeholders. Operational definitions, standards of procedure and protocols need to be developed and integrated into the system.

The paper has been presented at the “Youth Leadership Summit for Primary Health Care (YLS — PHC)” first National Conference on Family Medicine and Primary Care (FMPC 2013) on 20th and 21st April 2013 at the India International Center, New Delhi, India.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Declaration of Alma Ata, International Conference on Primary Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6-12. 1978. [Last cited on 2013 Jan 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/hpr/NPH/docs/declaration_almaata.pdf .

- 2.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, India. Rural Health Care System in India. NRHM Health Management Information's Systems Portal. [Last accessed on 2013 Jan 21]. Available from: http://www.nrhm-mis.nic.in/UI/RHS/RHS%202010/RHS%202010/Rural%20Health%20Care%20System%20in%20India.pdf .

- 3.Pardeshi GS. Primary Healthcare in India, Asian Hospital and Healthcare management. [Last accessed on 2013 Nov 30]. Available from: http://www.asianhhm.com/healthcare_management/primaryhealthcare-india.htm .

- 4.Kumar R. Academic Institutionalization of Community Services: Way Ahead in Medical Education. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2012;1:10–9. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.94442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhaumik S. Increase to India's health budget is not enough, say doctors. BMJ. 2013;346:f1428. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhaumik S, Biswas T. India's “rural doctor” proposal stirs criticism. CMAJ. 2012;184:E637–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee P, Biswas T, Datta A, Sriganesh V. Healthcare information and the rural primary care doctor. S Afr Med J. 2012 Feb 23;102:138–9. doi: 10.7196/samj.5672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhaumik S. Information technology in healthcare: Telemedicine. Your Health. 2012;61:16–8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao M, Mant D. Strengthening primary healthcare in India: White paper on opportunities for partnership. BMJ. 2012;344:e3151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biswas R, Joshi A, Joshi R, Kaufman T, Peterson C, Sturmberg JP, et al. Revitalizing primary health care and family medicine/primary care in India--disruptive innovation? J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15:873–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Govindarajan V. Telemedicine Can Cut Health Care Costs by 90%. HBR Blog Network. [Last accessed on 2012 Apr 23]. Available from: http://www.blogs.hbr.org/cs/2012/04/how_telemedicine_saves_lives_a.html .

- 12.Depar tment of Heal th and Ageing, Australian government. Building a 21st Century Primary Health Care System: A Draft of Australia's First National Primary Health Care Strategy. Australian Government. 2009. [Last accessed on 2013 Nov 30]. Available from: http://www.yourhealth.gov.au/internet/yourhealth/publishing.nsf/Content/nphc-draft-reporttoc/SFILE/NPHC-Draft.pdf .

- 13.Ink Spot Strategy. Schott's Vocan. [Last accessed on 2012 Nov 16]. Available from: http://www.schott.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/11/16/ink-spotstrategy/