Abstract

Background:

Acne is the most common disorder treated by dermatologists. As many as 80-90% of all adolescents have some type of acne and 30% of them require medical treatment. It is an inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit characterized by the formation of open and closed comedones, papules, pustules, nodules, and cysts.

Aims:

The present study was conducted to investigate the in vitro anti-acne activity of two Unani single drugs Darchini (Cinnamomum zeylanicum Bl.) and Tukhm Khashkhash (Papaver somniferum L. seeds).

Materials and Methods:

The antibacterial activity of aqueous, ethanolic and hydroalcoholic extracts of both drugs were investigated against two acne causing bacteria, i.e., Propionibacterium acne and Staphylococcus epidermidis using well diffusion method.

Results:

The result showed that both drugs were active against the two bacteria. Against P. acne aqueous and ethanolic extract of Darchini and Tukhm Khashkhash showed the zone of inhibition of 18 ± 1.02 mm and 18 ± 1.6 mm and 13 ± 1.04 mm and 14 ± 1.8 mm, respectively. Against S. epidermidis aqueous, hydroalcoholic and ethanolic extracts of Darchini showed 22 ± 1.7 mm, 22 ± 1.2 mm and 15 ± 1.8 mm zone of inhibition respectively. Hydroalcoholic and ethanolic extracts of Tukhm Khashkhash showed 15 ± 1.09 mm and 13 ± 1.6 mm zone of inhibition respectively.

Conclusion:

This suggests that C. zeylanicum and P. somniferum have potential against acne causing bacteria and hence they can be used in topical anti-acne preparations and may address the antibiotic resistance of the bacteria.

KEY WORDS: Acne, Propionibacterium acnes, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Unani

INTRODUCTION

Acne is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous units. It is characterized by seborrhea, the formation of open and closed comedones, erythematous papules, pustules and in more severe cases nodules, deep pustules, and pseudocysts. In many cases, a degree of scarring will ensue.[1] It is the most common disorder treated by dermatologists. There is a wide range of individual clinical expression with males tending to have more severe forms, the incidence is similar in males and females until mid-20s; thereafter acne is more prevalent in females, but the severity and frequency are markedly decreased.[2] Four major factors are involved in the pathogenesis: (i) Increased sebum production, (ii) hypercornification of the pilosebaceous duct, (iii) abnormality of the microbial flora, especially colonization of the duct with Propionibacterium acnes and (iv) inflammation.[1]

The sebum produced by acne patients has been shown to be deficient in linoleic acid, an essential fatty acid. This deficiency is associated with retention hyperkeratosis of the pilosebaceous follicle. Once the follicles have been occluded, bacteria, especially the Gram-positive anaerobic diphtheroids P. acnes, which inhabit the follicles at puberty but do not invade living tissue, produce lipases, which hydrolyze sebaceous gland triglycerides into free fatty acids. These acids, in combination with bacterial proteins and bits of keratin are then extruded through the dilated follicular wall into the dermis, producing a neutrophilic inflammatory response.[2] The process is mediated by production of interleukin-1α and tumor necrosis factor alpha by keratinocytes and T-lymphocytes with resultant increased proliferation of keratinocytes, diminished apoptosis and consequent hypergranulosis. Circulating androgens are also of importance in acne vulgaris, the development of the disease at puberty coinciding with arise in the levels of circulating androgens. Androgens directly stimulate sebum secretion and also hair growth.[3]

P. acnes are anaerobic obligate diphtheroids that reside beneath the surface of human skin and populate the androgen stimulated sebaceous follicles. The oxidative stress within the pilosebaceous unit changes the environment from aerobic to anaerobic which is the best suited for this Gram-positive bacterium. It causes inflammatory acne. Staphylococcus epidermidis is also the resident of human skin flora and is the aerobic organism associated with superficial infections within the sebaceous units.

Topical antimicrobial agents are the first line of treatment in mild to moderate acne vulgaris. The primary pathogenic agent implicated in the development of inflammatory acne is P. acnes. Over the past 20 years, concern has grown about the gradual worldwide increase in the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant P. acnes strains.[4] Topical antibiotics like erythromycin, the tetracyclines, and clindamycin have been used. There is the risk of producing colonies of resistant organisms.[5] Medicines other than the antibiotics like retinoids, isotretinoin cause erythema, burning, scaling, pruritus, and dryness.[6] Isotretinoin can cause serious birth defects in the developing fetus of a pregnant woman and can cause liver changes with raised serum lipid values.[7]

Currently used antibiotic agents are failing to bring an end to many bacterial infections due to super resistant strains. There are many approaches to search for new biologically active principles, which fight acne in plants. Systematic screening of Unani drugs may result in the discovery of novel effective compounds.[8]

Darchini consists of the dried inner bark of the coppiced shoots of the stem of Cinnamomum zeylanicum Blume.[9,10] It has been mentioned in Unani classical texts as a potent drug in the treatment of acne,[11,12] melasma,[12,13,14] abdominal pain, hiccups,[12,15] headache,[13,15] jaundice, vomiting, and diarrhea.[13] Modern scientific researches proved its antifungal,[16] antibacterial,[17] antiulcer,[18] and immunomodulatory[19] activities.

Tukhm Khashkhash (Papaver somniferum L. seeds) are the small white seeds obtained from the capsule of white poppy plant. It is used as an anti-inflammatory,[20] antispasmodic,[21] cardiotonic,[20] mild astringent,[22] emollient,[21] antitussive,[23] nutritive,[21,22] antidiarrheal,[23] and analgesic.[20,23]

These two drugs are used in the treatment of acne individually as well as in combination. Therefore, in the present study, an attempt has been made to investigate the in vitro anti-acne activity of the two Unani drugs Darchini and Tukhm Khashkhash.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

Bark of Darchini (C. zeylanicum) and seeds of Khashkhash (P. somniferum seeds) were purchased from K.R. Market Bangalore, Karnataka, India. The drugs were authenticated and identified by a botanist from Foundation for Revitalization of Local Health Traditions, Bangalore with Account number 2739 and 2740, respectively.

Preparation of the crude drugs

Aqueous, hydroalcoholic and alcoholic extract of both drugs were obtained using soxhlet apparatus.

For aqueous extract, both drugs (200 g each) were coarsely powdered and extracted with double distilled water with the help of soxhlet apparatus separately. The resulting extract was evaporated and dried over a water bath.

For hydroalcoholic extract, both drugs (200 g each) were coarsely powdered and extracted with double distilled water: ethanol (50:50) with the help of soxhlet apparatus separately. The resulting extract was evaporated and dried on water bath.

For alcoholic extract, both drugs (200 g each) were coarsely powdered and extracted with ethanol with the help of soxhlet apparatus separately. The resulting extract was evaporated and dried on water bath.

Microorganisms

Two acne causing test organisms, P. acnes (MTCC code - 1951) and S. epidermidis (MTCC code-435) were procured from Microbial Type Culture Collection, Institute of Microbial Technology, Chandigarh, India.

Determination of antibacterial activity

Determination of antibacterial activity was carried out at Microbiology lab of Azyme Biosciences, Jaya Nagar, Bangalore.

The antibacterial activity was determined by well diffusion method. S. epidermidis was cultured in nutrient broth at 37°C for 24 h under aerobic conditions and adjusted to yield approximately 1 × 108 CFU/mL. The agar plates were swabbed evenly with 100 μL of bacterial inoculum. A sterile 8 mm borer was used to cut wells of equidistance in each plate. The solutions of the extracts were prepared by dissolving 10 mg of each extract in 1 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide. Wells were filled with 50 μL, 100 μL of extract solution. Test repeat for Darchini extract by increasing the volume up to 500 μl. The plates were left at ambient temperature for 30 min to allow exceed prediffusion prior to incubation at 37°C for 24 h under aerobic conditions in an incubator.

P. acnes was incubated in brain heart infusion medium for 48 h under anaerobic conditions and adjusted to yield approximately 1 × 108 CFU/ml. The agar plates were swabbed evenly with 100 μL of bacterial inoculum. A sterile 8 mm borer was used to cut wells of equidistance in each plate. Wells were filled with 250 μL of extract solutions. The plates were left at ambient temperature for 30 min to allow exceed prediffusion prior to incubation at 37°C for 72 h under anaerobic conditions in a anaerobic bag with gas pack and indicator tablets and the bag was kept in an incubator for 72 h at 37°C. Gas packs containing citric acid, sodium carbonate and sodium borohydride were used to maintain and check the anaerobiosis. The indicator tablet of methylene blue changed from dark pink-blue-light pink finally, which indicated the achievement of anaerobic condition. All tests were performed in triplicates. The antibacterial activity was evaluated by measuring the diameter of zone of inhibition (in mm).[24,25,26]

RESULTS

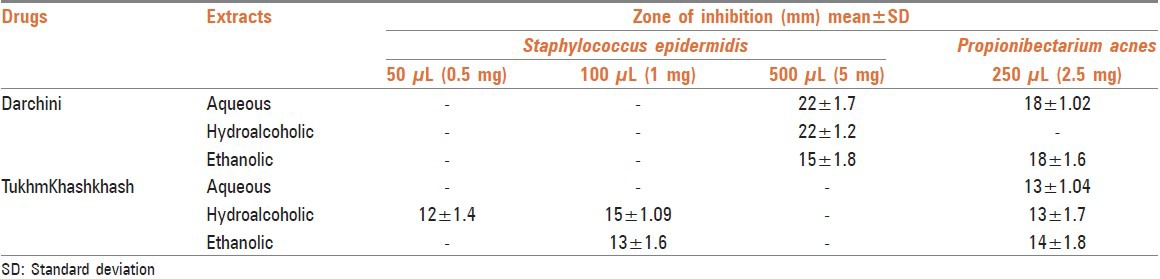

The zone of inhibition for aqueous and ethanolic extracts of Darchini against P. acnes was 18 ± 1.02 mm and 18 ± 1.6 mm respectively. Similarly, the zone of inhibition for aqueous and ethanolic extracts of Tukhm Khashkhash was 13 ± 1.04 mm and 14 ± 1.8 mm respectively. The zone of inhibition for aqueous, hydroalcoholic and ethanolic extracts of Darchini measured 22 ± 1.7 mm, 22 ± 1.2 mm and 15 ± 1.8 mm respectively against S. epidermidis. The inhibition zone measured 15 ± 1.09 mm and 13 ± 1.6 mm for hydroalcoholic and ethanolic extracts of Tukhm Khashkhash respectively [Table 1]. Hydroalcoholic extract of Darchini did not exhibit any activity against P. acnes at 2.5 mg concentration. Ethanolic extract of Tukhm Khashkhash also fail to exhibit any activity against S. epidermidis at 0.5 mg concentration.

Table 1.

Antibacterial activity of Darchini and Tukhme khashkhash

DISCUSSION

In bio-medicine topical antimicrobial agents such as erythromycin, tetracycline and clindamycin are the first line of treatment in mild to moderate acne vulgaris. However, gradual worldwide increase in the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant P. acnes strains has drawn the attention towards the alternative system of medicines. Among them, drugs used in Unani system of medicine are time-tested, centuries old, safe for use and cost effective. It is also proved that many Unani drugs have antibacterial activity. Some in vitro studies revealed that coriander leaves and Terminalia arjuna bark were found to be active against P. acne and S. epidermidis.[24,27] Britto et al.[28] evaluated aqueous and methanolic extracts of poppy seeds for antibacterial activity against the antibiotic resistant phytopathogenic strain Xanthomonas campestris. Their results showed zone of inhibition of 11.35 ± 0.52 mm and 10.15 ± 0.65 mm for aqueous and methanolic extracts respectively at a concentration of 100 mg/ml. Likewise, Rahman et al.[29] also found antibacterial activity of poppy seeds against Micrococcus luteusa food spoilage bacterium. Antibacterial activity of Cinnamon against many bacteria is also proved. Rahman et al.[29] found Cinnamon to have an inhibitory effect against seven food spoilage pathogens among them Staphylococcus aureus and C. albicans were found to be the most susceptible. Essential oil of C. zeylanicum was found to check the growth of Vibrio cholera and Salmonella paratyphi.[30] But until date, no study have been reported the antibacterial activity of Darchini and Tukhm Khaskhash against P. acne and S. epidermidis. In the present study, Darchini do not show any activity against S. epidermidis at the concentration of 50 μL and 100 μL. However, when the concentration is increased to 500 μL a good zone of inhibition was noted. This activity may be due to the presence of phenolic compounds in Darchini such as cinnamaldehyde, acetic acid 1 - octyl acetate, eugenol, etc. In case of Tukhm Khaskhash aqueous extract has no zone of inhibition but hydroalcoholic extract shows zone of inhibition at 50 μL and 100 μL concentrations. Against P. acnes all the extracts of both drugs at a concentration of 250 μL shows zone of inhibition, except hydroalcoholic extract of Darchini.

In classical Unani literature, Darchini is mentioned in the treatment of acne,[11] this activity may be due to its action of mufatteh (deobstruent), muhallil (anti-inflammatory) and jazib (absorbefacient) and is also claimed that it corrects all types of ufoonat (infection) of akhlat (humor).[11,12] As the mizaj (temperament) of Tukhm Khashkhash is barid (cold), it soothes the inflammatory condition of skin diseases.[12]

This study shows that P. acnes is more sensitive to ethanolic extracts of Darchini and Tukhm Khashkhash than other extracts, whereas hydroalcoholic extracts of both the drugs have good activity against S. epidermidis than other extracts. Therefore, Darchini (C. zeylanicum Bl) and Tukhm Khashkhash (P. somniferum L. seeds) are active against the two acne causing bacteria, i.e., P. acneand S. epidermidis.

CONCLUSION

The aqueous, hydroalcoholic and ethanolic extracts of Darchini and Tukhm Khashkhash were found to have potency against acne inducing bacteria. Activity of these drugs can be further evaluated in animal and clinical trials so that they can be developed into formulations and used commercially for treatment of acne.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. 8th ed. Vol. 1. UK: Wiley-Blackwell Ltd; 2010. Rook's Text book of Dermatology; p. 42.17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sams WM, Lynch PJ. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996. Principle and Practice of Dermatology; pp. 801–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mckee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. USA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005. Pathology of the Skin with Clinical Correlations; pp. 1116–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leyden JJ. Antibiotic resistance in the topical treatment of acne vulgaris. Cutis. 2004;73:6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buxton PK. 4th ed. London: BMJ Publishing Group Ltd; 2003. ABC of Dermatology PDF eBook; pp. 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Draelos ZD, Thaman LA. New York: Taylor and Francis; 2006. Cosmetic Formulation of Skin Care Products; pp. 251–2. [Google Scholar]

- 7. [Last accessed on 2013 Mar 10]. p. 2. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm197220.pdf .

- 8.Grover A, Bhandari BS, Rai N. Antimicrobial activity of medicinal plants-Azadirachta indica A. Juss, Allium cepa L. and Aloe vera L. Int J PharmTech Res. 2011;3:1059–65. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Part-I. Vol. 1. New Delhi: CCRUM, Ministry of H and F.W. Govt. of India; 2007. The Unani Pharmacopoeia of India; pp. 26–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Part-I. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Ministry of H and F.W. Govt. of India; 2001. The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India; pp. 113–4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baghdadi IH. 2nd ed. New Delhi: CCRUM; 2005. Kitab Almukhtarat Fil Tibb. Part; p. 100. Urdu Translation. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baitar I. 3rd ed. Vol. New Delhi: Dept. of AYUSH, Ministry of H and FW. Govt. of India; 1999. Aljame al Mufradat al Advia wa al Aghzia. Urdu translation by CCRUM; pp. 170–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghani N. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Idara Kitabus Shifa; 1971. Khazainul Advia; pp. 682–4. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibrahim AS. 1st ed. New Delhi: Faculty of Unani Medicine, Jamia Hamdard; 2007. Kitab al-Fath fi al-Tadawi (Urdu Translation) pp. 90–1. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hakeem MA. New Delhi: Idara Kitabus Shifa; 2002. Bustanul Mufradat; pp. 266–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray AB, Sarma BK, Singh UP. 1st ed. Lucknow: International Book Distributing Co; 2004. Medicinal Properties of Plants: Antifungal, Antibacterial and Antiviral Activities; p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nasir M. Addis Ababa University; Thesis. The antimicrobial effect of essential oils on dermatophytes. Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, School of Graduate Studies. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alqasoumi S. Anti-secretagogue and antiulcer effects of ‘Cinnamon’ Cinnamomum zeylanicum in rats. J Pharmacognosy Phytother. 2012;4:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flores RG, Martinez HH, Guerra PT, Guerra RT, Licea RQ, Cuevas EM, et al. Antitumor and immunomodulating potential of Coriandrum sativum, Piper nigrum and Cinnamomum zeylanicum. J Nat Prod. 2010;3:54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kulkarni PH, Ansari S. 1st ed. Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications; 2004. The Ayurvedic Plants; p. 98. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khare CP. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2007. Indian Medicinal Plant: An Illustrated Dictionary; pp. 150–1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nadkarni KM. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan Private Limited; 2009. Indian Materia Medica; pp. 328–30. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prajapati ND, Kumar U. Jodhpur: Agrobios Publication India; 2003. Agro's Dictionary of Medicinal Plants; p. 80. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vats A, Sharma P. Formulation and evaluation of topical anti acne formulation of coriander extract. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2012;16:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kokare C. 8th ed. Pune: Nirali Prakashan; 2011. Pharmaceutical Microbiology-Principles and Applications; pp. 19.1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhatt DC, Ali A. 4th ed. Delhi: Birla Publications; 2008-9. Pharmaceutical Microbiology-Concepts and Techniques; pp. 119–24. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vijayalakshmi A, Tripura A, Ravichandiran V. Development and evaluation of anti-acne product from Terminalia arjuna bark. Int J ChemTech Res. 2011;3:320–7. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Britto AJ, Gracelin DH, Benjamin P, Kumar JR. Antibacterial potency and synergistic effects of a few South Indian spices against antibiotic resistant bacteria. Indian J Nat Prod Resour. 2012;3:557–62. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahman SA, Thangaraj S, Salique SM, Khan KF. Natheer SE Antimicrobial and biochemical analysis of some spices extract against food spoilage pathogens. Int J Food Saf. 2010;12:71–5. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Usha M, Ragini S, Naqvi SM. Antibacterial activity of acetone and ethanol extracts of cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum) and Ajowan (Trachyspermum ammi) on four food spoilage bacteria. Int Res J Biol Sci. 2012;1:7–11. [Google Scholar]