Abstract

N-terminal acetylation is among the most ubiquitous of protein modifications in eukaryotes. While loss of N-terminal acetylation is associated with many abnormalities, the molecular basis of these effects is known for only a few cases, where acetylation of single factors has been linked to binding avidity or metabolic stability. In contrast, the impact of N-terminal acetylation for the majority of the proteome, and its combinatorial contributions to phenotypes, are unknown. Here, by studying the yeast prion [PSI+], an amyloid of the Sup35 protein, we show that loss of N-terminal acetylation promotes general protein misfolding, a redeployment of chaperones to these substrates, and a corresponding stress response. These proteostasis changes, combined with the decreased stability of unacetylated Sup35 amyloid, reduce the size of prion aggregates and reverse their phenotypic consequences. Thus, loss of N-terminal acetylation, and its previously unanticipated role in protein biogenesis, globally resculpts the proteome to create a unique phenotype.

Introduction

First identified as a covalent mark on tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) proteins and histones more than 50 years ago, the acetylation of proteins on their N-termini has emerged as one of the most widespread modifications in eukaryotic proteomes, impacting ~85% of proteins in humans and ~50% of proteins in yeast.1 This modification is placed on the α-amino group of a protein during its synthesis by a conserved family of ribosome-bound N-terminal acetyltransferases (types A through F), whose specificity is determined primarily by the amino acid at the mature N-terminus of the substrate.2,3 Thus, N-terminal acetylation, like initiator methionine removal, is a component of the basal maturation pathway for nascent polypeptides.3

Despite this widespread, constitutive and seemingly irreversible transfer pathway, loss of N-terminal acetylation induces an array of distinct phenotypes. In yeast, mating, transcriptional silencing, proteasome activity, mitochondrial and vacuolar inheritance, viral capsid assembly, heat sensitivity, sporulation, propagation of the [PSI+] prion, and entry into G0 are all modulated by N-terminal acetylation.4–8 In humans, mutations in N-terminal acetyltransferases have been linked to the developmental disorder Ogden syndrome9,10 and to an increasing number of cancers.11 Notably, these phenotypic changes are specific to the loss of distinct N-terminal acetyltransferases, implicating the modification of unique protein substrates in these varied biological outcomes.

While these observations underscore the significant contributions of N-terminal acetylation to cellular homeostasis, the target of the crucial acetylation and the precise mechanism by which this modification alters protein activity have only been elucidated for a limited number of phenotypes in relation to the number of N-terminally acetylated proteins present in a eukaryotic cell.2 Based on these studies, the N-terminal acetyl group has been shown to mediate specific protein interactions or to alter the metabolic stability of proteins.2,12,13 However in the few cases in which the N-terminal acetylation has been linked to a phenotypic change, the latter event can be explained by the loss of an acetyl group from a single substrate, which impacts a single in vivo characteristic of that protein. Thus, the combinatorial effects of N-terminal acetylation and the possibility of a global function for this ubiquitous modification remain significant unanswered questions.2

Intriguingly, early studies demonstrated a role for N-terminal acetylation in the stabilization of α-helices in peptides,14–16 and this effect extends to proteins to varying degrees in vitro.17–19 N-terminal acetylation occurs on polypeptides after the synthesis of ~50 amino acids.20 Given the fact that the vast majority of eukaryotic proteins are thought to fold co-translationally,21 the timing and constitutive nature of N-terminal acetylation ideally positions it for a previously unexplored role in protein folding.22

To address this possibility, we studied the interaction between N-terminal acetylation and a protein conformation-based (prion) trait in S. cerevisiae. The [PSI+] prion confers a heritable translation termination defect through the assembly of Sup35, the eukaryotic release factor 3, into ordered, self-templating amyloid aggregates.23 However, the resulting stop codon read through can be genetically separated from the presence of Sup35 aggregates by disruption of the N-terminal acetyltransferase NatA (a heterodimer of the Nat1 and Ard1 proteins), which restores accurate termination to a [PSI+] strain.3,7 Our studies on this system have uncovered a role for N-terminal acetylation in global protein folding. In the absence of this modification, misfolded proteins accumulate in cells and induce a stress response. The resulting elevation of chaperone proteins, their titration by the accumulating misfolded substrates, and their increased efficiency in processing aggregates of unacetylated Sup35 alters the steady-state size of these complexes and their ability to disrupt translation termination.

Results

Sup35 N-terminal acetylation stabilizes prion aggregates

Our previous qualitative analysis of the Sup35 N-terminus by mass spectrometry suggested that this protein was not a NatA target,7 but a subsequent quantitative analysis, following the specific isolation of N-terminally acetylated proteins, conclusively identified Sup35 as a NatA substrate.1 This observation, along with the known effects of N-terminal acetylation on protein interactions,22 raised the possibility that loss of Sup35 N-terminal acetylation could impact the prion-associated phenotype because Sup35 aggregation is mediated through its N-terminal prion-determining domain.24

According to the (X)PX rule, the presence of a proline at the second position in an open reading frame blocks N-terminal acetylation.25 To determine the contribution of Sup35 N-terminal acetylation to prion propagation, we created a [PSI+] strain expressing a Sup35 mutant with a Ser-to-Pro substitution at the second position (Sup35S2P) as the sole copy of the protein. Because disruption of NatA reduces the thermodynamic stability and therefore the size of Sup35 aggregates,7 we first assessed the sensitivity of Sup35S2P aggregates to disruption in SDS at various temperatures.26 Sup35S2P aggregates isolated from an otherwise isogenic WT strain also exhibited reduced stability in comparison with WT Sup35 aggregates. However, when compared with the Sup35 aggregates isolated from a ΔNatA strain, the Sup35S2P aggregates were disrupted at a higher temperature (70–75°C vs. 65–70°C), indicating a slightly increased stability (Fig. 1a). Consistent with this intermediate stability, Sup35 aggregates were composed of smaller core polymers in the SUP35(S2P) strain in comparison with the WT strain, as assessed by semi-denaturing detergent agarose gel electrophoresis (SDD-AGE),27 but not to the same degree as observed in a ΔNatA strain (Fig. 1b).7

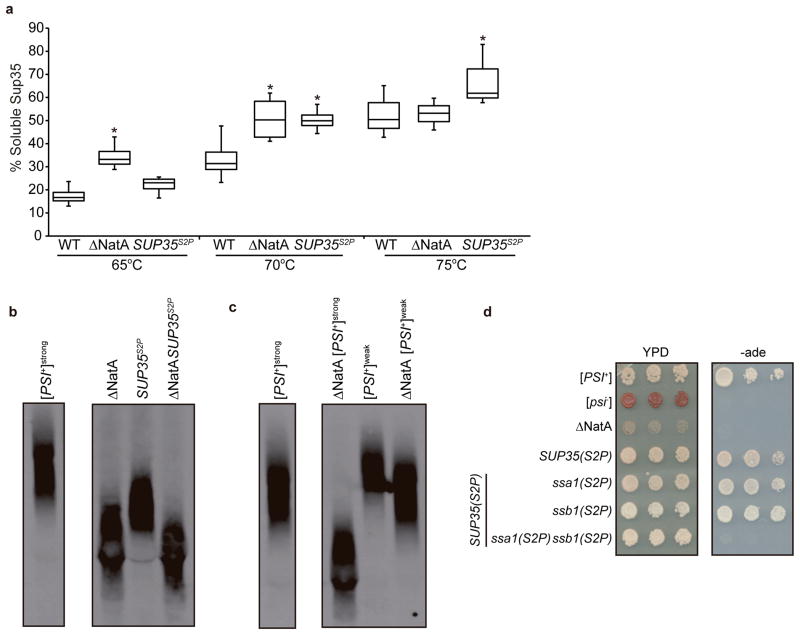

Fig. 1. N-terminal acetylation of specific factors impacts Sup35 prion aggregate stability, size and associated phenotype.

a. Lysates from WT (SLL2606), ΔNatA (SY319), and SUP35(S2P) (SY1209) [PSI+] strains were incubated in SDS at the indicated temperatures before separation by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for Sup35 The percentage of Sup35 detected at the indicated temperatures relative to 100°C is plotted. Horizontal lines on boxes indicate 25th, 50th, and 75th percentiles; error bars indicate 10th and 90th percentiles (n=6; *p≤ 0.001 by unpaired Student’s t-test in comparison with WT [PSI+] at the same temperature). b. Lysates isolated from WT and ΔNatA [PSI+] strains expressing Sup35 (SLL2606, SY319, respectively) or Sup35S2P (SY1209, SY2154, respectively) were analyzed by semidenaturing detergent agarose gel electrophoresis (SDD-AGE) followed by immunoblotting for Sup35 (samples shown were run in non-contiguous lanes on the same gel). c. Lysates isolated from [PSI+] WT and ΔNatA strains propagating the [PSI+]strong (SLL2606 and SY319, respectively) or [PSI+]weak (SLL2600 and SY1132, respectively) conformation were analyzed by SDD-AGE followed by immunoblotting for Sup35 (samples shown were run in non-contiguous lanes on the same gel). d. 10-fold serial dilutions of cultures of WT ([PSI+] and [psi−]) (SLL2606 and SLL2119), [PSI+] ΔNatA (SY319), [PSI+] SUP35(S2P) (SY1209), [PSI+] SUP35(S2P) ssa1(S2P) (SY1339), [PSI+] SUP35(S2P) ssb1(S2P) (SY1965), [PSI+] SUP35(S2P) ssa1(S2P) ssb1(S2P) (SY2182) expressing strains were grown on rich medium (YPD) and medium lacking adenine (−ade) at 30°C.

While Sup35S2P aggregates had reduced thermodynamic stability, the amino acid substitution itself could mediate its effect independent of changes in Sup35 N-terminal acetylation. However, combining the Sup35S2P mutation with a disruption of NatA did not lead to the accumulation of even smaller Sup35 aggregates in comparison with those isolated from the ΔNatA strain alone (Fig. 1b), suggesting that these two changes act through the same pathway. If disruption of NatA is indeed altering prion propagation by lowering Sup35 aggregate thermodynamic stability, yeast strains propagating a more thermodynamically stable variant of [PSI+], such as [PSI+]weak,28 should be less sensitive to this effect. Consistent with this prediction, disruption of NatA led to the accumulation of smaller Sup35 aggregates in a [PSI+]weak strain, but the size of the core polymers was larger than those isolated from the ΔNatA [PSI+]strong strain, which propagates the less thermodynamically stable variant that was used throughout the rest of these studies (Fig. 1c). Thus, the reduced thermodynamic stability of aggregates of non-acetylated Sup35 is the first molecular event in the modulation of [PSI+] propagation in a ΔNatA strain.

To explore the cellular consequences of this reduced thermodynamic stability, we next assessed the prion-associated phenotype. While disruption of NatA reversed the adenine prototrophy associated with the [PSI+]-dependent read through of the premature stop codon in the ade1-14 allele in our strain background,29 the SUP35(S2P) and WT strains were phenotypically indistinguishable (Fig. 1d). Thus, loss of Sup35 N-terminal acetylation alone is not sufficient to restore accurate termination to a [PSI+] strain, suggesting that additional factors contribute to the ΔNatA [PSI+] phenotype.

Loss of N-terminal acetylation induces a stress response

Given the protein-conformation basis of the prion-associated phenotype, we next considered the possibility that global loss of N-terminal acetylation in a ΔNatA strain could also reverse the [PSI+] phenotype through a general perturbation of protein folding. To test this idea, we assessed activation of the two major cellular stress responses that sense protein homeostasis (proteostasis) in the cytoplasm: the environmental stress response (ESR),30,31 which is regulated by the Msn2/4 transcription factors,32 and the heat shock response (HSR),33,34 which is regulated by the Hsf1 transcription factor.35 Disruption of NatA in a [PSI+] strain had only a modest effect on Msn2/4-mediated reporter gene expression (Fig. 2a) but induced a five-fold increase in Hsf1-mediated reporter gene expression (Fig. 2b). Intriguingly, this Hsf1-mediated response corresponded to only a slight elevation in the protein levels of the heat-inducible Hsp70 family members (Ssa3/4), suggesting a mild stress (Supplementary Fig. 1a).36 Nonetheless, the protein levels of constitutively expressed, but also Hsf1-inducible, molecular chaperones that have been previously implicated in [PSI+] propagation, including Hsp104, Hsp70 (Ssa1/2, Ssb1/2), and Hsp40 (Sis1), were all elevated (Fig. 2c).23 Notably, disruption of either NatB (a heterodimer of the Nat3 and Mdm20 proteins) or NatC (a heterotrimer of the Mak3, Mak10, and Mak31 proteins), the other major N-terminal acetyltransferases in S. cerevisiae,3 failed to elevate chaperone protein levels, although disruption of NatB did induce both Hsf1 and Msn2/4-mediated reporter gene expression (Supplementary Fig. 1a–d).

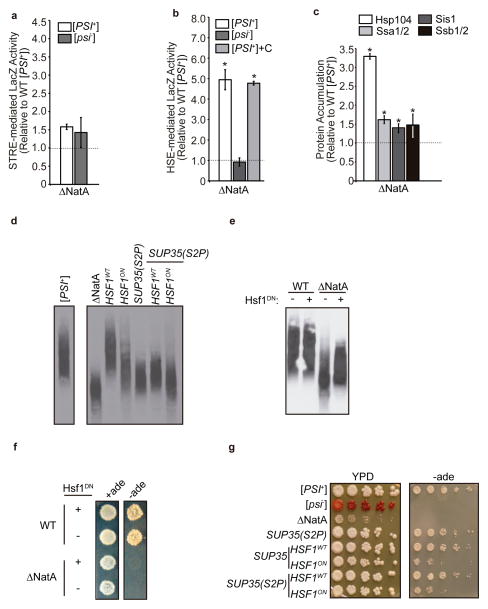

Fig. 2. Loss of N-terminal acetylation induces an Hsf-1 mediated stress response, which impacts prion propagation.

a. Stress response element (pSTRE) activity was analyzed using a β-galactosidase reporter (SB757) expressed in ΔNatA [PSI+] (SY319) or [psi−] (SY978) strains relative to a WT [PSI+] strain (SLL2606). (n=6, error bars represent standard deviation). b. Heat shock element (pHSE) activity was analyzed using a β-galactosidase reporter (SB753) expressed in ΔNatA [psi−] (SY978) and [PSI+] (SY319) strain and in a ΔNatA [PSI+] (SY319) strain also expressing the C-terminal domain of Sup35 (+C; SLL6676) relative to a WT [PSI+] strain (SLL2606). (n=6, *p<0.00001 by unpaired Student’s t-test compared to WT [PSI+], error bars represent standard deviation) c. Expression of Hsp104, Ssa1/2, Sis1, and Ssb1/2 was determined by analyzing lysates of a [PSI+] ΔNatA strain (SY319) by SDS-PAGE followed by quantitative Western blot using specific antisera relative to WT [PSI+] (SLL2606) lysates. (n=6, p<0.005 by unpaired Student’s t-test compared to WT [PSI+], error bars represent standard deviation). d. Lysates from WT (SLL2606), ΔNatA (SY319), SUP35(S2P) (SY1209), HSF1ON (SY2130), and SUP35(S2P) HSF1ON (SY2124) [PSI+] strains were analyzed by SDD-AGE followed by immunoblotting for Sup35. e. Lysates from [PSI+] WT (SLL2606) and ΔNatA strains (SY319) expressing a dominant-negative Hsf1 mutant (Hsf1DN; SB778) or an empty vector (−) were analyzed by SDD-AGE -followed by immunoblotting for Sup35. f. Cultures of WT (SLL2606) and ΔNatA [PSI+] (SY319) strains expressing Hsf1DN (+) or an empty vector (−) were spotted on complete medium (+ade) and medium lacking adenine (−ade) before incubation at 30°C. g. 10-fold serial dilutions of WT [PSI+] (SLL2606) and [psi−] (SLL2119), [PSI+] ΔNatA (SY319), [PSI+] SUP35(S2P) (SY1209), [PSI+] HSF1ON (SY2130), and [PSI+] SUP35(S2P) HSF1ON (SY2129) strains were grown on rich medium (YPD) and medium lacking adenine (−ade) at 30°C.

As disruption of NatB or NatC has no effect on the [PSI+] phenotype,7 we considered the possibility that the elevation of chaperones in a ΔNatA strain could perturb Sup35 aggregate dynamics and thereby provide an explanation for the reversal of the prion-associated phenotype. To test this idea, we expressed an Hsf1 mutant (Hsf1ON), which constitutively binds to its response elements and activates the HSR in the absence of an inducing signal,37 as the sole copy of the transcription factor in an otherwise WT [PSI+] strain. Hsf1ON expression induced a dose-dependent elevation of Hsf1 activity (Supplementary Fig. 1e) and Hsp104, Hsp70 and Sis1 chaperone levels (Fig. S1f) and led to the accumulation of smaller Sup35 aggregates (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 2a). Thus, the elevation of Hsf1 activity mimics the effects of NatA disruption on Sup35 aggregate size. To determine if Hsf1-mediated gene expression directly contributed to the effects of NatA disruption on the [PSI+] phenotype, we down-regulated the HSR in a ΔNatA [PSI+] strain by expressing a dominant-negative mutant of Hsf1 (Hsf1DN), which decreases its affinity for its response elements.38 Upon Hsf1DN expression in a ΔNatA [PSI+] strain, Hsf1-mediated activity (Supplementary Fig. 1g) and Hsp104 and Hsp70 (Ssa1/2) levels were greatly reduced (Supplementary Fig. 1h), but Sis1 levels compensatorily increased (Supplementary Fig. 1h). Corresponding to these changes, the smallest Sup35 core polymers were lost in a ΔNatA but not a WT strain (Fig. 2e, Supplementary Fig. 2b). Thus, the Hsf1-mediated elevation of molecular chaperones is a second molecular event in the modulation of [PSI+] propagation in a ΔNatA strain.

We noted, however, that manipulation of Hsf1 activity in ΔNatA or WT strains did not completely suppress or recapitulate, respectively, the effects of NatA disruption on Sup35 aggregate size (Fig. 2d, e). To determine the effect of these manipulations on the [PSI+] phenotype, we monitored growth of these strains on medium lacking adenine, which requires the read through of the premature stop codon in the ade1-14 allele. Consistent with the partial effects on Sup35 aggregate size (Fig. 2d, e), expression of Hsf1DN failed to restore the [PSI+] phenotype in a ΔNatA strain (Fig. 2f), but expression of Hsf1ON did partially reverse the [PSI+] phenotype in a WT strain (Fig. 2g).

ΔNatA defects synergistically modulate prion propagation

The two molecular defects that we have uncovered in a ΔNatA strain (i.e. the decreased stability of unacetylated Sup35 core polymers and chaperone elevation) contributed only partial effects on Sup35 aggregate size and the prion-associated phenotype. Although these defects are distinct, we predicted that they would act synergistically on prion propoagation because both of these factors are predicted to impact Sup35 core particle size.39 To determine if chaperone elevation and reduced aggregate thermodynamic stability were sufficient in combination to phenocopy the ΔNatA effect on [PSI+] propagation, we constructed a [PSI+] strain that expresses both Hsf1ON and Sup35S2P as the sole copy of each factor in an otherwise WT background. Consistent with our prediction, smaller Sup35 aggregates accumulated in the double-mutant strain in comparison with the single-mutant strains (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Fig. 2a), indicating that the two effects were synergistic. However, the substitution of Sup35S2P for WT Sup35 did not further reverse the [PSI+] phenotype beyond the level observed in the Hsf1ON strain (Fig. 2g). Taken together, these observations suggest that, while both loss of Sup35 N-terminal acetylation and increased chaperones combinatorily contribute to the effect of NatA disruption on prion propagation, other factor(s) must also contribute to this outcome.

Misfolded proteins alter the processing of Sup35 aggregates

One factor that we had yet to consider in the modulation of prion propagation by loss of NatA is the presence of other (non-prion) misfolded proteins, which provide a signal to activate the HSR.33 Because NatA predominantly modifies its targets co-translationally,22 we considered the possibility that co-translational protein folding would be perturbed upon disruption of NatA. Disruption of other factors that promote co-translational protein maturation, such as chaperones, confers sensitivity to translational inhibitors, presumably due to the combined effects of these conditions on co-translational folding capacity.40 While disruption of the post-translationally acting chaperone Sti1 had no effect on the growth of a [PSI+] strain in the presence of translational inhibitors, disruption of NatA, NatB, or NatC conferred sensitivity to translational inhibitors. The severity of this sensitivity mirrored the induction of an Hsf1-mediated response in these strains (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1b, 3a), suggesting a role for N-terminal acetylation in co-translational protein biogenesis. Consistent with this interpretation, expression of the NatA, NatB and NatC N-terminal acetyltransferases cluster with components of the translation machinery and the chaperones linked to protein synthesis (CLIPs) rather than with post-translationally acting, stress-responsive chaperones (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

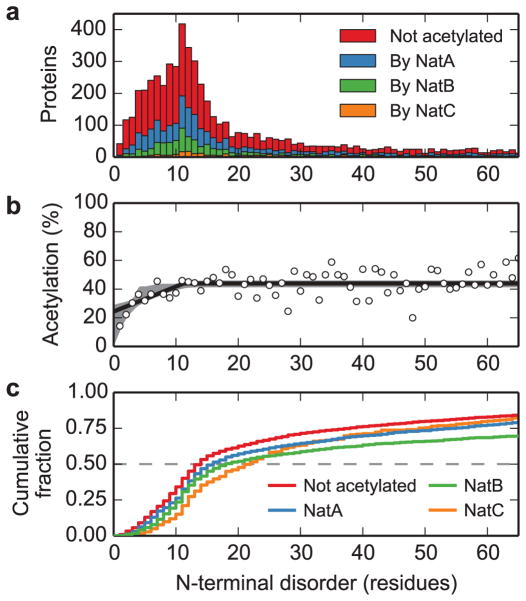

Given this link between co-translational folding and N-terminal acetylation, we reasoned that this modification would most likely exert its effects locally. To explore this possibility, we analyzed the relationship between N-terminal acetylation propensity and N-terminal structural flexibility in the yeast proteome using bioinformatics. Most yeast proteins (~80%) are predicted to have a continuous disordered region that is less than 65 residues beginning at the N terminus (Fig. 3a). Strikingly, the overall probability of a protein being N-terminally acetylated depends strongly on the length of the N-terminal disordered region (Fig. 3b), rising from a probability of 24% (95% confidence interval: 0–29%) for proteins with no N-terminal disorder to a stable probability of 44% (95% confidence interval: 41–46%) when the length of the N-terminal disordered region exceeds 11.3 residues (95% confidence interval: 4.0–15.8 residues). Moreover, proteins that are predicted to lack an N-terminal acetyl group have shorter N-terminal disordered regions (median length 14 residues) than proteins that are predicted to be N-terminally acetylated by NatA (median length 16 residues), NatB (median length 18 residues), and Nat C (median length 22 residues; Fig. 3c). This relationship correlates with the sensitivity of NatA and NatB strains to translational inhibitors (Supplementary Fig. 3a), and while NatC falls outside of this correlation, we note that this enzyme targets fewer substrates with very long N-terminal disordered regions than NatA or NatB (Fig. 3a). Thus, N-terminal acetylation may play a role in the structural stabilization of N-terminally flexible proteins.

Fig. 3. N-terminal acetylation correlates with structural flexibility at the N terminus.

a. The distributions of the lengths of N-terminal disordered regions for the yeast proteome are shown as a function of acetylation status: non-acetylated (red) and acetylated by NatA (blue), NatB (green) and NatC (orange). b. The fraction of proteins predicted to be acetylated is shown as a function of the length of predicted disordered region (points), including the maximum-likelihood threshold model (solid line) and 95% confidence interval from modeling (grey shaded region). This model fits the data significantly better than a model with constant probability of acetylation (likelihood ratio test: difference in log-likelihood = 25.9, 2 degrees of freedom, p < 10−11). c. The cumulative fraction of proteins with length of N-terminal disorder less than or equal to the given values, by acetylation status (color as described in panel a). These distributions are all significantly different from each other (pairwise two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests, all p < 2×10−3, see Supplementary Table 4 for details).

As predicted by these analyses, disruption of NatA in a [PSI+] strain led to the accumulation of protein aggregates, as assessed by a centrifugation assay, but this effect was greatly reduced in a [psi−] strain (Fig. 4a). Because this difference cannot be directly attributed to the pelleting of Sup35 aggregates themselves (Supplementary Fig. 4), [PSI+] must place an additional load on proteostasis in a ΔNatA strain. This increased load was also reflected in the sensitivity of ΔNatA strains to translational inhibitors (Supplementary Fig. 3a), their level of Hsf1-mediated gene expression (Fig. 2b), and their doubling times (Table 1), which were all reduced by prion loss (i.e. conversion to [psi−]).

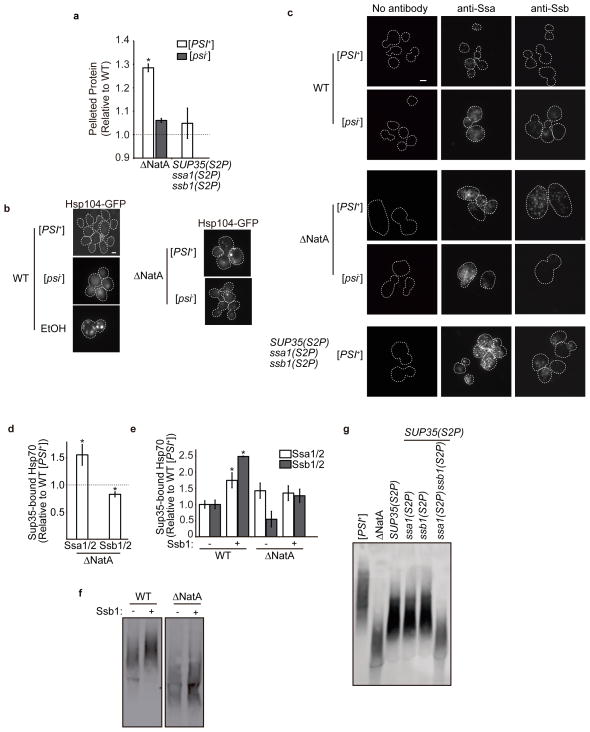

Fig. 4. Loss of N-terminal acetylation induces general protein misfolding, which alters prion propagation through chaperone titration.

a. Lysates from ΔNatA ([PSI+] and [psi−], SY319 and SY978, respectively) and [PSI+] SUP35(S2P) ssa1(S2P) ssb1(S2P) (SY2182) strains were centrifuged at 15,000 × g, and the amount of pelleted protein was quantified and compared to that isolated from a WT [PSI+] (SLL2606) strain. (n=6, *p<0.005 by unpaired Student’s t-test compared to WT [PSI+], error bars represent standard deviation). b. Hsp104-GFP localization was assessed in WT [PSI+] (SY1906) and [psi−] (SY2125) strains, in the WT [PSI+] strain treated with 7.5% ethanol, and in ΔNatA [PSI+] (SY2152) and [psi−] (SY2183) strains by microscopy. Scale bars represent 10μm. c. Cells from WT [PSI+] (SLL2606) and [psi−] (SY2119), ΔNatA [PSI+] (SY319) and [psi−] (SY978) and [PSI+] SUP35(S2P) ssa1(S2P) ssb1(S2P) (SY2182) strains were fixed, and Ssa1/2 and Ssb1/2 proteins were visualized by immunofluorescence using specific antisera. Scale bars represent 10μm. d. Sup35 was immunocaptured from [PSI+] WT (SLL2606) and ΔNatA [PSI+] strains, and co-captured Ssa1/2 and Ssb1/2 was assessed following SDS-PAGE and quantitative immunoblotting using specific antisera. The levels of bound Hsp70s were normalized to the precipitated Sup35 and compared to the levels isolated from the WT [PSI+] (SY1500) strain. (n=4, *p<0.05 by unpaired Student’s t-test, error bars represent standard error) e. The relative amount of Hsp70s bound to Sup35 aggregates in [PSI+] WT (SY1500) and ΔNatA (SY1502) strains containing either empty vector (white) or an Ssb1-expressing plasmid (SB806) plasmids (gray) were determined as in (d). (n=4, *p<0.04 by unpaired Student’s t-test, error bars represent standard error) f. Lysates isolated from [PSI+] WT (SLL2606) and ΔNatA (SY319) strains containing either empty vector (−) or an Ssb1-expressing plasmid (+) (SB806) were analyzed by SDD-AGE followed by immunoblotting for Sup35. g. Lysates from [PSI+] WT (SLL2606), ΔNatA (SY319), SUP35S2P (SY1209), SUP35(S2P) ssa1(S2P) (SY2123), SUP35(S2P) ssb1(S2P) (SY2195), and SUP35(S2P) ssa1(S2P) ssb1(S2P) (SY2182) strains were analyzed by SDD-AGE followed by immunoblotting for Sup35.

Table 1.

Strain Doubling Times

| Strain | [PSI] | YPD | Vector | Sup35C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | + | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| − | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 | |

| ΔNatA | + | 2.6 | 3.2 | 3.3 |

| − | 2 | 2.4 | 2.5 | |

| Δssb1/2 | + | 4 | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| − | 3 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

Doubling time (h) in YPD medium for [PSI+] (+) and [psi−] (−) WT (SLL2606 and SLL2119, respectively), ΔNatA (SY319 and SY978, respectively), and Δssb1/2 (SY394 and SY441, respectively) strains. Strains were also transformed with either an empty vector or a plasmid expressing the C-terminal domain of Sup35 (Sup35C, SLL6676), and doubling times were determined in SD–Ura medium.

The presence of [PSI+] could exacerbate the effects of NatA disruption either through Sup35 aggregates themselves or alternatively through the translation termination defect associated with them. However, neither Hsf1-mediated gene expression (Fig. 2b) nor the extended doubling-time (Table 1) observed in a ΔNatA [PSI+] strain were reversed by expression of an N-terminally truncated mutant of Sup35 (Sup35C), which restores translation termination fidelity without perturbing Sup35 aggregates.24 These observations indicate that Sup35 aggregates, rather than their phenotypic effects, synergize with disruption of NatA to perturb proteostasis.

One mechanism to explain the interaction of misfolded protein and Sup35 aggregates is a competition between these species for molecular chaperones.41 To monitor chaperone engagement, we first assessed their localization in cells. A functional Hsp104-GFP fusion protein, which retains the ability to support [PSI+] propagation (data not shown), localized to cytoplasmic foci (Fig. 4b), which presumably represent misfolded protein aggregates, in both [PSI+] and [psi−] ΔNatA strains more frequently than in their WT counterparts, although the magnitude of this effect was much reduced in comparison with a severe stress (7.5% ethanol; Fig. 4b, S5a). By immunofluorescence, both Ssa1/2 and Ssb1/2 had a similarly enhanced localization to cytoplasmic foci in a [PSI+] ΔNatA strain relative to its WT counterpart, and this localization pattern was also evident for Ssa1/2 in a [psi−] ΔNatA strain (Fig. 4c, S5b). Thus, while loss of N-terminal acetylation increased the abundance of Ssa1/2 substrates, the presence of [PSI+] did not further effect the localization of this chaperone. In contrast, Ssb1/2 localization was greatly reduced in the [psi−] ΔNatA strain in comparison with its [PSI+] counterpart (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 5b). Consistent with this observation, the doubling time of an Δssb1/2 strain was extended in the presence of [PSI+], and this extension was not reversed by expression of Sup35C (Table 1). These observations suggest that the presence of prion aggregates specifically promoted the appearance of Ssb1/2 substrates in the absence of NatA.

To explore the possibility of substrate competition for chaperones, we immunoprecipitated Sup35 from ΔNatA and WT strains and compared the levels of bound Hsp70 chaperones. Consistent with the competition hypothesis, the level of Ssb1/2 bound to Sup35 was reduced by ~30% in the ΔNatA strain (Fig. 4d), and this change corresponded to an increase in Sup35-bound Ssa1/2 by ~50% in the ΔNatA strain (Fig. 4d). Because genetic experiments have linked Ssa1/2 to promotion of the prion state but Ssb1/2 to its destabilization,42,43 we reasoned that these changes in the Hsp70 family member bound could alter the size of Sup35 aggregates and their phenotypic consequences in a ΔNatA strain. To test this idea, we attempted to restore WT Hsp70:Sup35 bound ratios by overexpressing Ssb1 in a ΔNatA strain (Supplementary Fig. 6). While this treatment did not reduce the level of bound Ssa1/2, presumably due to its own elevated expression (Fig. 2c), it did restore Ssb1/2 binding to Sup35 to the WT level (Fig. 4e), suggesting that Ssb1/2 availability was limiting in the [PSI+] ΔNatA strain. Surprisingly, Ssb1 overexpression in a [PSI+] ΔNatA strain did not deplete the small Sup35 core polymers (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 2c), but overexpression of Ssb1 in a WT strain increased its binding to Sup35 (Fig. 4e) and depleted the smallest Sup35 core polymers (Fig. 4f, Supplementary Fig. 2c). This observation indicates that changes in Hsp70 binding can impact prion aggregate dynamics, implicating a third molecular event in the modulation of [PSI+] propagation in a ΔNatA strain.

Hsp70 N-terminal acetylation is required for activity

The failure of Ssb1/2 overexpression to increase the size of Sup35 core polymers in the ΔNatA strain could arise from their reduced thermodynamic stability (Fig. 1a), but we also considered the possibility that loss of N-terminal acetylation of Ssa1/2 and/or Ssb1/2, which are known NatA targets,1 could negatively impact their activities. To test this possibility, we first monitored chaperone expression as a readout for Ssa1/2 and Ssb1/2 activity in a [PSI+] strain expressing the Ssa1S2P, Ssb1S2P, and Sup35S2P mutants as the sole copy of each factor. These mutations were integrated into the genome of a strain that was also disrupted for the corresponding Hsp70 paralogs (i.e. ssa1(S2P)Δssa2 or ssb1(S2P)Δssb2, hereafter referred to as ssa1(S2P) or ssb1(S2P), respectively). In this triple-mutant strain, Sis1 expression was elevated to a level similar to that observed in a ΔNatA [PSI+] strain (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 7). Ssa1/2 levels, however, were reduced 50% relative to those observed in the ΔNatA [PSI+] strain (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 7), an effect that can be explained by the disruption of SSA2 in the ssa1(S2P) background (Supplementary Fig. 7). Hsp104 levels were also elevated by ~50% relative to WT (Supplementary Fig. 7), but this elevation was significantly reduced relative to the ΔNatA strain, which accumulated over 300% more Hsp104 than a WT strain (Fig. 2c). Consistent with this dampened induction of Hsp104, the triple-mutant [PSI+] strain did not significantly accumulate protein aggregates in comparison with the ΔNatA [PSI+] strain (Fig. 4a), although both Ssa1S2P and Ssb1S2P localized to cytoplasmic foci in the former (Fig. 4c, Supplementary Fig. 5B), indicating the presence of some misfolded proteins in both the presence and absence of [PSI+]. Together, these observations suggest that, while N-terminal acetylation of Ssa1 and Ssb1 is likely important for their chaperone activities, the accumulation of misfolded protein aggregates and the corresponding cellular response to this change in proteostasis cannot be explained solely by Hsp70 impairment.

We next assessed [PSI+] propagation in the presence of these non-acetylatable mutants. Introduction of either the ssa1(S2P) or ssb1(S2P) alleles alone into the SUP35(S2P) strain did not reduce the size of Sup35 aggregates (Fig. 4g) or revert the [PSI+] phenotype (Fig. 1d) beyond the effects of Sup35S2P expression alone. However, when all three alleles are combined into a single strain, the size of Sup35 core polymers approaches that observed in a ΔNatA strain (Fig. 4g), and accurate termination is restored to a [PSI+] strain (Fig. 1d). These observations cannot be linked to the ssa1(S2P) or ssb1(S2P) changes individually (Fig. S8) and contrasted with the partial effects observed in a strain with constitutive Hsf1 activity (Hsf1ON) and reduced core polymer thermodynamic stability (Sup35S2P) in the absence of misfolded proteins (Fig. 2d, g, S2a). Thus, the accumulation of misfolded protein aggregates, the elevation of chaperone expression and the destabilization of Sup35 aggregates are sufficient, when combined, to recapitulate the effects of NatA disruption on prion propagation.

Discussion

Our studies have revealed novel insights into the contribution of N-terminal acetylation to cellular phenotypes. First, the effect of NatA on the [PSI+] phenotype is the first example, to our knowledge, of a trait that is dependent upon the N-terminal acetylation of multiple targets. Second, N-terminal acetylation contributes an unanticipated influence on protein biogenesis, both through and independent of Hsp70 activity (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 7). Together, these events converge on Sup35 aggregate dynamics to promote the accumulation of smaller complexes, which our parallel studies have demonstrated to be functionally engaged and therefore capable of reversing the [PSI+] phenotype.44 Thus, loss of N-terminal acetylation can resculpt the proteome to create complex cellular phenotypes.

While post-translational modifications have not previously been implicated in protein folding outside of the secretory pathway, a role for N-terminal acetylation in the stabilization of N-terminal alpha helices had been previously recognized in vitro,14–19 and ΔNatA strains have increased sensitivity to thermal stress, consistent with our observation of elevated protein aggregation and the corresponding titration of molecular chaperones to these complexes (Fig. 4b,c). More recently, this modification has been implicated in the quality control of stoichiometry for multiprotein complexes, where uncomplexed subunits are targeted for degradation based on the acetylation state of their exposed N-termini.13 An example of the potential effects of N-terminal acetylation on protein structure that has been demonstrated at atomic resolution is the silent information regulator Sir3, which requires N-terminal acetylation for its transcriptional silencing activities at a mating-type locus and telomeres in yeast. Sir3 crystal structures indicate that N-terminal acetylation of this protein mediates the formation of a fine structural element that are required for function.45,46 Notably, the mating defect associated with loss of Sir3 N-terminal acetylation can be partially suppressed by overexpression of the Hsp70 chaperone Ssb1.20 Moreover, mutations in Sir3 that synergize with disruption of NatA to promote a more severe mating defect (E131K, T135I, L208S, S813R)47 are predicted to alter aggregation potential and/or disorder in Sir3 (Supplementary Fig. 9), and several of these mutations occur in secondary structural elements (T135I, L208S, S813R).47 In contrast, mutations which do not enhance the ΔNatA mating defect (A2T, R30K, R92K, L95F, E140K)47 do not alter disorder or aggregation potential and are located in unstructured regions of the protein, with the exception of E140K (Supplementary Fig. 10). Together, these observations are consistent with the introduction a folding defect in Sir3 upon loss of N-terminal acetylation that can be exacerbated by other covalent changes to the protein. In theory, the contribution of N-terminal acetylation to protein folding that we have uncovered could extend to other post-translational modifications, providing an alternative explanation for the abundant “non-functional” protein modifications identified by comparative proteomics.48

Beyond the system-wide changes in proteostasis that we have identified, our studies also uncover a direct role for N-terminal acetylation of Sup35 in the processing of its aggregated form in vivo. In the absence of this modification, the thermodynamic stability of these complexes is reduced (Fig. 1a) even though the extreme N-terminus of the protein lies outside of the amyloid core,49 suggesting that the effect cannot be explained by direct interactions between monomers. Some insight, however, may be gleaned from recent studies on the Parkinson’s Disease associated protein α-synuclein, which is also N-terminally acetylated in vivo.50–53 In this case, N-terminal acetylation, again occurring outside of the amyloid core, has been shown to stabilize a transient N-terminal helix, which may partially impede amyloid formation.54–56 Together, these examples highlight the emerging, and currently underexplored, contributions of post-translational modifications to amyloidogenesis and its biological consequences.

N-terminal acetylation was previously thought to be a basal and unregulated modification. However, recent studies have uncovered variation in the extent of acetylation of individual factors and fluctuations in the ratio of acetylated: unacetylated protein, suggesting a window for regulating protein stability and activity.2 Indeed, the sensitivity of tissue culture cells to apoptotic signals,57 cell and population sizes in growing yeast cultures,58 and photosynthesis59 are all likely regulated by a shift in the acetylation state of distinct proteins in response to changing environmental and metabolic conditions. These variations and the links to protein biogenesis reported here provide a new framework for identifying the molecular basis of changes in physiology associated with N-terminal acetylation, such as cancer,11,22 and perhaps with other seemingly “non-functional” protein modifications.

Methods

Plasmids

All primers and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Plasmids for expression of the HSF1 dominant-negative allele (EXA3-1; SB778 in our collection) and wildtype HSF1 (SB779 in our collection) were provided by E. Craig (University of Madison – Wisconsin).38 To create the constitutively active HSF1ON allele (SB788), a R206S mutation was installed in SB779 by site-directed mutagenesis using Quick Change (Stratagene) with primers 5′ Hsf1 R206S and 3′ Hsf1 R206S according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To create high copy (2μ) constructs, the promoter and ORF were excised from SB779 and SB788 as an EcoRI-XhoI restriction fragment and ligated into pRS426 or pRS42460 to yield SB812 and SB806, respectively. pHSE-LacZ (SB753 in our collection) and pSTRE-LacZ (SB757 in our collection) were provided by K. Morano (University of Texas Medical School at Houston). The SSB1 over expression plasmid (SB806) was created by cloning the Ssb1 ORF as a BamHI-XhoI fragment by PCR, using primers 5′Ssb1 WT and 3′ Ssb1 and ligating this fragment into pRS424-pGPD.60 The ssb1(S2P) plasmid (SB732) was created by amplifying the SSB1 promoter region as a SacI-BamHI fragment by PCR using primers 5′ pSsb1 and 3′ pSsb1 and ligating this fragment into pRS306.60 The SSB1 ORF was then inserted following amplification by PCR using primers 5′Ssb1 WT or 5′ Ssb1 S2P and 3′ Ssb1 primers. All clones were verified by sequencing.

Yeast Strains

All strains of S. cerevisiae used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 3. All yeast strains are derivatives of 74-D69429. The HSF1 ORF was disrupted by transformation of an hphMX4 cassette61, amplified by PCR using primers 5′ Hsf1 KO and 3′ Hsf1, into diploid cells. Disruptions were confirmed by resistance to hygromycin B and by PCR using the primer pairs 5′ Hsf1 Seq/pTEF CHK and 3′Hsf1 Seq/pFA6a. The heterozygous disruption strain was transformed with plasmids expressing either WT (SB779) or an HSF1 mutant (SB778, SB806) and sporulated. Haploids were isolated by micromanipulation and screened for hygromycin B resistance and retention of the Hsf1 plasmid. SUP35(S2P) strains were created by substituting SUP35(S2P) for WT SUP35 at its endogenous locus by two-step replacement using BsrGI-digested SB548. The replacement was confirmed by PCR, as previously described 61. The SSB1 and SSB2 ORFs were disrupted by transformation of kanMX4 or HIS3MX6 cassettes amplified by PCR using primers 5′ Ssb1KO/3′ Ssb1 KO or 5′ Ssb2 KO/3′ Ssb2 KO, respectively. ssb1(S2P) strains were created by digesting SB732 with NcoI to target the integration to the URA3 locus. Insertions were confirmed by uracil prototrophy and western blotting. Combinations of SUP35(S2P), ssa1(S2P), and ssb1(S2P) within the same haploid strain were created by mating the single-mutant strains, sporulating the resulting diploids, and isolating the meiotic progeny by micromanipulation. The STI1 ORF was disrupted by transformation of the kanMX6 cassette, amplified by PCR using primers 5Sti1pFA6a and 3Sti1pFA6a. Genotypes were confirmed by PCR analysis of the meiotic progeny. Sup35-HA expressing strains (SY1500 and SY1502) were created by integrating AflII-digested SB629 into WT or NatA strains. The [psi−] version of these strains were made by curing the prion by growth on 3mM guanidine HCl plates.

β-Galactosidase Activity Assay

β-Galactosidase activity was assayed in duplicate and experiments repeated using three independent transformations using the protocol described previously 62. Briefly, cells were grown in liquid selective medium, harvested, washed, and lysed in Z buffer (10mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.0, 10mM KCl, 1mM MgSO, and 50mM β-mercaptoethanol) with 0.01% SDS and 10% chloroform with vortexing. Activity was assayed using the substrate ONPG(2-Nitrophenyl β-D-galactopyranoside) by absorbance at 420nm following quenching of the reaction with sodium bicarbonate. To calculate the specific β-galactosidase activity: ((1000*A420)/(OD600*mL of culture harvested))*(time of ONPG incubation in minutes).

Protein Analysis

Semi-denaturing detergent agarose gel electrophoresis (SDD-AGE), SDS-PAGE, quantitative immunoblot, and thermal melt were performed as previously described7. SDD-AGE assesses the size of SDS-resistant core polymers of prion proteins, which assemble into larger SDS-sensitive complexes in vivo.27 For this technique, cells were grown in liquid YPAD, harvested, washed, and mechanically disrupted in buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1mM DTT, 2mM PMSF, and 5 μg/ml Pepstatin) with glass beads. Lysates were cleared at 500×g for 1 minute at 4°C, and normalized lysates were separated on a 1.5% Tris-glycine agarose gel containing 0.1%SDS, transferred to PVDF membrane, and analyzed by immunoblotting using Sup35-specific antiserum (1:2000 dilution). For thermal melt analysis, cells were grown in liquid YPAD, harvested, washed, and mechanically disrupted in buffer (10mM sodium phosphate pH7.5, 0.2% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 400mM NaCl, 2mM PMSF, 5μg/ml pepstatin) with glass beads. Lysates were collected and incubated in 2% SDS at the indicated temperatures for 5 minutes prior to separation by SDS-PAGE and quantitative analysis by immunoblotting using Sup35-specific antiserum (1:2000 dilution), goat anti-rabbit 488 DyLight secondary (Thermo), a Typhoon Imager (GE Life Sciences), and ImageQuant software.

Quantification of Non-prion Protein Aggregates

50 OD600 equivalents of cells were grown to mid-log phase and then collected and washed at 4°C. Cells were disrupted by glass bead lysis in 500μl of lysis buffer (50mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 1mM DTT, 2mM PMSF, and 5 μg/ml Pepstatin) using a FastPrep-24 (MP Bio). Lysates were centrifuged at 500×g for 5 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. The protein concentration of the supernatant was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad), and normalized lysates were centrifuged at 15000×g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and pelleted proteins were washed in buffer (50mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.5, 25mM NaCl) and collect by a second centrifugation at 15000×g at 4°C for 15 min. The supernatant was removed, and the protein pellet was resuspended in 50μl of wash buffer, and the protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-rad). Samples were analyzed in duplicate, and experiments were repeated at least three times.

Immunocapture of Protein Complexes

Immunocapture of protein complexes was performed as previously described 63. Briefly, yeast strains were grown in liquid YPD, harvested, washed, and mechanically lysed in PEB lysis buffer (40mM TrisHCl pH 7.6, 150mM KCl, 5mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 2mM PMSF (fresh) 5μg/ml pepstatin, protease inhibitor tablet (Roche), protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma)) with glass beads. Lysates were then cleared by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 10 minutes at 4°C, and the final concentration of Triton X-100 was adjusted to 1% and of KCl to 350mM. Immunoprecipitation was performed with an anti-HA rat monoclonal antibody (Clone 3F10, Roche Applied Sciences) and Protein G Magnetic Beads (NEB). Beads were captured in a magnetic field, and washed 1x in wash buffer A (40mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 300mM KCl, 5mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100), 2 × in wash buffer B (40mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 150mM KCl, 5mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100), and 1 × in wash buffer C (40mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 150mM KCl, 5mM MgCl2, 500mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100). Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF. Membranes were immunoblotted using serum specific for Sup35 (polyclonal rabbit, 1:2000 dilution), Ssa1/2 (polyclonal rabbit, 1:20,000 dilution, gift of E. Craig), and Ssb1/2 (polyclonal rabbit, 1:5,000 dilution, gift of J. Frydman). Bands were quantified using goat anti-rabbit DyLight secondary (Thermo) using a Typhoon Imager (GE Life Sciences) and ImageQuant software.

Cluster analysis

Clustering was performed by the Stanford Microarray Database 64 using a previously published dataset 65. Standard statistical thresholds were used. Genes clustered were selected according to GO terms for translational components and molecular chaperones.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence was performed as previously described 66. Spheroplasts were incubated with no primary antibody, 1:5,000 dilution of anti-Ssa1/2, or 1:1,000 dilution of anti-Ssb1/2. Cells were washed in TBS + 0.01% TWEEN20. A goat anti-rabbit qDot 655 (Invitrogen) was used as secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:500, and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Spheroplasts were washed 2X in TBS + 0.03% TWEEN20 and 2X in TBS + 0.01% TWEEN20. Cells were observed using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 equipped with a ×100 αPlan-FLUAR objective and a Hamamatsu-ORCA ER camera (Hamamatsu Photonics). Images were collected with Openlabs software (Improvision) at 516-nm excitation and 575–615 emission, and pseudocolored using Openlabs software. Scale bars were applied using ImageJ software. Samples were repeated at least 3 times.

Bioinformatics

Sequences for 6696 Saccharomyces cerevisiae known or novel proteins were obtained from Ensembl release 60. Cleavage of the N-terminal methionine and N-terminal acetylation were predicted as described previously.67 As previously described,68 we scored MN as acetylated, although it is predicted to lead to acetylation in only 55% of cases. Incorporating this incomplete acetylation does not change our qualitative results, although it does preclude us from fitting models by maximum-likelihood. The acetyltransferase responsible for acetylating each protein was identified based on the target protein sequence.22 To predict intrinsic disorder, the protein sequences (with the N-terminal methionine cleaved or not as appropriate) were analyzed using SPINE-D,69 which uses a neural network algorithm to predict regions of intrinsic disorder. Two proteins failed to run, because their sequences included stop codons, leaving 6694 proteins in our final analysis. Models for the probability of acetylation versus length of N-terminal disordered region were fit by maximum likelihood, using SciPy.70 To focus our modeling, only proteins with N-terminal disorder regions of length 65 or smaller were fit in the model. Confidence intervals on model parameters were inferred by bootstrapping over the entire set of proteins 1,000 times.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Laney and members of the Serio and Laney labs for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript and J. Frydman (Stanford University), E. Craig (University of Wisconsin – Madison), and K. Morano (University of Texas Medical School at Houston) for reagents. We also thank Siddharth Pandya (University of Arizona) for assistance running SPINE-D. This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM069802) to TRS, and an Achievement Rewards for College Scientists scholarship to BKM.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The studies described here were designed by WMH, BKM, RNG, and TRS, performed by WMH and BKM, and analyzed by WMH, BKM, RNG, and TRS. The manuscript was written by WMH, BKM, RNG, and TRS.

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Arnesen T, et al. Proteomics analyses reveal the evolutionary conservation and divergence of N-terminal acetyltransferases from yeast and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8157–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901931106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnesen T. Towards a functional understanding of protein N-terminal acetylation. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001074. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polevoda B, Sherman F. N-terminal Acetyltransferases and Sequence Requirements for N-terminal Acetylation of Eukaryotic Proteins. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:595–622. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01269-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whiteway M, Szostak JW. The ARD1 gene of yeast functions in the switch between the mitotic cell cycle and alternative developmental pathways. Cell. 1985;43:483–92. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aparicio OM, Billington BL, Gottschling DE. Modifiers of position effect are shared between telomeric and silent mating-type loci in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1991;66:1279–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90049-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polevoda B, Cardillo TS, Doyle TC, Bedi GS, Sherman F. Nat3p and Mdm20p are required for function of yeast NatB Nalpha-terminal acetyltransferase and of actin and tropomyosin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:30686–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304690200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pezza JA, et al. The NatA acetyltransferase couples Sup35 prion complexes to the [PSI+] phenotype. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1068–80. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-04-0436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiza V, Molina-Serrano D, Kyriakou D, Hadjiantoniou A, Kirmizis A. N-alpha-terminal acetylation of histone H4 regulates arginine methylation and ribosomal DNA silencing. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003805. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rope AF, et al. Using VAAST to identify an X-linked disorder resulting in lethality in male infants due to N-terminal acetyltransferase deficiency. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:28–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Damme P, Støve SI, Glomnes N, Gevaert K, Arnesen TA. Saccharomyces cerevisiae model reveals in vivo functional impairment of the Ogden syndrome N-terminal acetyltransferase Naa10S37P mutant. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.035402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kalvik TV, Arnesen T. Protein N-terminal acetyltransferases in cancer. Oncogene. 2013;32:269–76. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim HK, et al. The N-Terminal Methionine of Cellular Proteins as a Degradation Signal. Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shemorry A, Hwang CS, Varshavsky A. Control of protein quality and stoichiometries by N-terminal acetylation and the N-end rule pathway. Mol Cell. 2013;50:540–51. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fairman R, Shoemaker KR, York EJ, Stewart JM, Baldwin RL. Further studies of the helix dipole model: effects of a free alpha-NH3+ or alpha-COO-group on helix stability. Proteins. 1989;5:1–7. doi: 10.1002/prot.340050102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doig AJ, Chakrabartty A, Klingler TM, Baldwin RL. Determination of free energies of N-capping in alpha-helices by modification of the Lifson-Roig helix-coil therapy to include N- and C-capping. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3396–403. doi: 10.1021/bi00177a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shoemaker KR, Kim PS, York EJ, Stewart JM, Baldwin RL. Tests of the helix dipole model for stabilization of alpha-helices. Nature. 1987;326:563–7. doi: 10.1038/326563a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarvis JA, Ryan MT, Hoogenraad NJ, Craik DJ, Hoj PB. Solution structure of the acetylated and noncleavable mitochondrial targeting signal of rat chaperonin 10. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1323–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chakrabartty A, Doig AJ, Baldwin RL. Helix capping propensities in peptides parallel those in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:11332–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenfield NJ, Stafford WF, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. The effect of N-terminal acetylation on the structure of an N-terminal tropomyosin peptide and alpha alpha-tropomyosin. Protein Sci. 1994;3:402–10. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gautschi M, et al. The yeast N(alpha)-acetyltransferase NatA is quantitatively anchored to the ribosome and interacts with nascent polypeptides. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:7403–14. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7403-7414.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Netzer WJ, Hartl FU. Recombination of protein domains facilitated by co-translational folding in eukaryotes. Nature. 1997;388:343–9. doi: 10.1038/41024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Starheim KK, Gevaert K, Arnesen T. Protein N-terminal acetyltransferases: when the start matters. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37:152–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuite MF, Serio TR. The prion hypothesis: from biological anomaly to basic regulatory mechanism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:823–833. doi: 10.1038/nrm3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ter-Avanesyan MD, Dagkesamanskaya AR, Kushnirov VV, Smirnov VN. The SUP35 omnipotent suppressor gene is involved in the maintenance of the non-Mendelian determinant [PSI+] in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1994;137:671–6. doi: 10.1093/genetics/137.3.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goetze S, et al. Identification and functional characterization of N-terminally acetylated proteins in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e1000236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Satpute-Krishnan P, Serio TR. Prion protein remodelling confers an immediate phenotypic switch. Nature. 2005;437:262–5. doi: 10.1038/nature03981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kryndushkin DS, Alexandrov IM, Ter-Avanesyan MD, Kushnirov VV. Yeast [PSI+] prion aggregates are formed by small Sup35 polymers fragmented by Hsp104. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:49636–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307996200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka M, Collins SR, Toyama BH, Weissman JS. The physical basis of how prion conformations determine strain phenotypes. Nature. 2006;442:585–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chernoff YO, Lindquist SL, Ono B, Inge-Vechtomov SG, Liebman SW. Role of the chaperone protein Hsp104 in propagation of the yeast prion-like factor [PSI+] Science. 1995;268:880–4. doi: 10.1126/science.7754373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gasch AP, et al. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:4241–57. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Causton HC, et al. Remodeling of yeast genome expression in response to environmental changes. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:323–37. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.2.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Treger JM, Schmitt AP, Simon JR, McEntee K. Transcriptional factor mutations reveal regulatory complexities of heat shock and newly identified stress genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26875–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trotter EW, et al. Misfolded proteins are competent to mediate a subset of the responses to heat shock in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44817–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204686200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akerfelt M, Morimoto RI, Sistonen L. Heat shock factors: integrators of cell stress, development and lifespan. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:545–55. doi: 10.1038/nrm2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sorger PK, Pelham HR. Purification and characterization of a heat-shock element binding protein from yeast. EMBO J. 1987;6:3035–41. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Werner-Washburne M, Craig EA. Expression of members of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp70 multigene family. Genome. 1989;31:684–9. doi: 10.1139/g89-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sewell AK, et al. Mutated yeast heat shock transcription factor exhibits elevated basal transcriptional activation and confers metal resistance. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25079–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.25079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Halladay JT, Craig EA. A heat shock transcription factor with reduced activity suppresses a yeast HSP70 mutant. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4890–7. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.9.4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Derdowski A, Sindi SS, Klaips CL, DiSalvo S, Serio TR. A size threshold limits prion transmission and establishes phenotypic diversity. Science. 2010;330:680–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1197785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albanese V, Yam AY, Baughman J, Parnot C, Frydman J. Systems analyses reveal two chaperone networks with distinct functions in eukaryotic cells. Cell. 2006;124:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirstein-Miles J, Scior A, Deuerling E, Morimoto RI. The nascent polypeptide-associated complex is a key regulator of proteostasis. EMBO J. 2013;32:1451–68. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chernoff YO, Newnam GP, Kumar J, Allen K, Zink AD. Evidence for a Protein Mutator in Yeast: Role of the Hsp70-Related Chaperone Ssb in Formation, Stability, and Toxicity of the [PSI] Prion. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8103–8112. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Newman GP, Wegrzyn RD, Lindquist SL, Chernoff YO. Antagonistic Interactions between Yeast Chaperones Hsp104 and Hsp70 in Prion Curing. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1325–33. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pezza JA, Villali J, Sindi S, Serio TR. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang D, et al. Nalpha-acetylated Sir3 stabilizes the conformation of a nucleosome-binding loop in the BAH domain. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1116–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arnaudo N, et al. The N-terminal acetylation of Sir3 stabilizes its binding to the nucleosome core particle. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1119–21. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stone EM, Reifsnyder C, McVey M, Gazo B, Pillus L. Two classes of sir3 mutants enhance the sir1 mutant mating defect and abolish telomeric silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2000;155:509–22. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lienhard GE. Non-functional phosphorylations? Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:351–2. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toyama BH, Kelly MJ, Gross JD, Weissman JS. The structural basis of yeast prion strain variants. Nature. 2007;449:233–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bartels T, Choi JG, Selkoe DJ. alpha-Synuclein occurs physiologically as a helically folded tetramer that resists aggregation. Nature. 2011;477:107–10. doi: 10.1038/nature10324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohrfelt A, et al. Identification of novel alpha-synuclein isoforms in human brain tissue by using an online nanoLC-ESI-FTICR-MS method. Neurochem Res. 2011;36:2029–42. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0527-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sarafian TA, et al. Impairment of mitochondria in adult mouse brain overexpressing predominantly full-length, N-terminally acetylated human alpha-synuclein. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e63557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson JP, et al. Phosphorylation of Ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of alpha-synuclein in familial and sporadic Lewy body disease. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29739–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kang L, Janowska MK, Moriarty GM, Baum J. Mechanistic insight into the relationship between N-terminal acetylation of alpha-synuclein and fibril formation rates by NMR and fluorescence. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e75018. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kang L, et al. N-terminal acetylation of alpha-synuclein induces increased transient helical propensity and decreased aggregation rates in the intrinsically disordered monomer. Protein Sci. 2012;21:911–7. doi: 10.1002/pro.2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fauvet B, et al. Characterization of semisynthetic and naturally Nalpha-acetylated alpha-synuclein in vitro and in intact cells: implications for aggregation and cellular properties of alpha-synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28243–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.383711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yi CH, et al. Metabolic regulation of protein N-alpha-acetylation by Bcl-xL promotes cell survival. Cell. 2011;146:607–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Albertin W, et al. Linking post-translational modifications and variation of phenotypic traits. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:720–35. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.024349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoshiyasu S, et al. Potential involvement of N-terminal acetylation in the quantitative regulation of the epsilon subunit of chloroplast ATP synthase under drought stress. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77:998–1007. doi: 10.1271/bbb.120945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sikorski RS, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wach A, Brachat A, Pohlmann R, Philippsen P. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1793–808. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rupp S. LacZ assays in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2002;350:112–31. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)50959-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.DiSalvo S, Derdowski A, Pezza JA, Serio TR. Dominant prion mutants induce curing through pathways that promote chaperone-mediated disaggregation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:486–92. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hubble J, et al. Implementation of GenePattern within the Stanford Microarray Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D898–901. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gasch AP, et al. Genomic expression responses to DNA-damaging agents and the regulatory role of the yeast ATR homolog Mec1p. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2987–3003. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adams AE, Pringle JR. Relationship of actin and tubulin distribution to bud growth in wild-type and morphogenetic-mutant Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:934–45. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.3.934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Martinez A, et al. Extent of N-terminal modifications in cytosolic proteins from eukaryotes. Proteomics. 2008;8:2809–31. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Forte GM, Pool MR, Stirling CJ. N-terminal acetylation inhibits protein targeting to the endoplasmic reticulum. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang T, et al. SPINE-D: accurate prediction of short and long disordered regions by a single neural-network based method. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2012;29:799–813. doi: 10.1080/073911012010525022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oliphant TE. Python for scientific computing. Computing in Science and Engineering. 2007;9 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.