Abstract

Aims

Detrusor underactivity, resulting in either prolonged or inefficient voiding, is a common clinical problem for which treatment options are currently limited. The aim of this report is to summarize current understanding of the clinical observation and its underlying pathophysiological entities.

Methods

This report results from presentations and subsequent discussion at the International Consultation on Incontinence Research Society (ICI-RS) in Bristol, 2013.

Results and Conclusions

The recommendations made by the ICI-RS panel include: Development of study tools based on a system’s pathophysiological approach, correlation of in vitro and in vivo data in experimental animals and humans, and development of more comprehensive translational animal models. In addition, there is a need for longitudinal patient data to define risk groups and for the development of screening tools. In the near-future these recommendations should lead to a better understanding of detrusor underactivity and its pathophysiological background.

Keywords: ageing, detrusor underactivity, experimental animal models, lower urinary tract symptoms, underactive bladder, urinary tract physiology, voiding dysfunction

INTRODUCTION

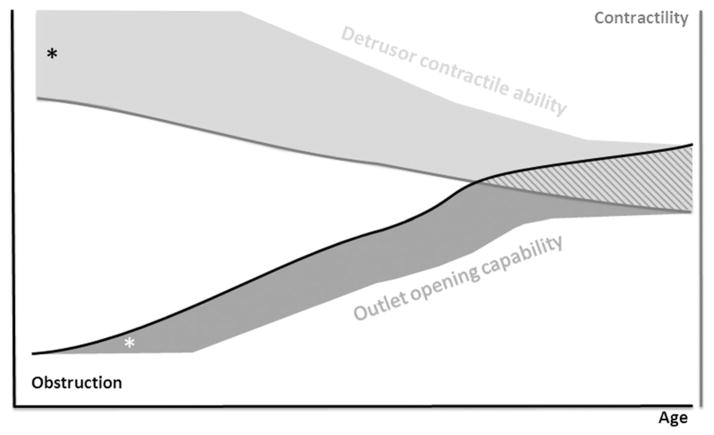

Detrusor underactivity has been defined by the International Continence Society as as a contraction of reduced strength and/or duration, resulting in prolonged bladder emptying and/or a failure to achieve complete bladder emptying within a normal time span.1 Successful and complete emptying is necessarily determined by the interplay of several factors including the ability of the bladder to empty, and the resistance offered by the outflow tract (i.e., the capacity of outlet opening). Diminished bladder emptying may occur because of reduced detrusor contractile ability (not equivalent to contractility), an impairment of the outflow tract or a combination of these factors. To a certain extent, both factors may be able to compensate for each other but this compensatory capacity may change in association with disease and ageing.

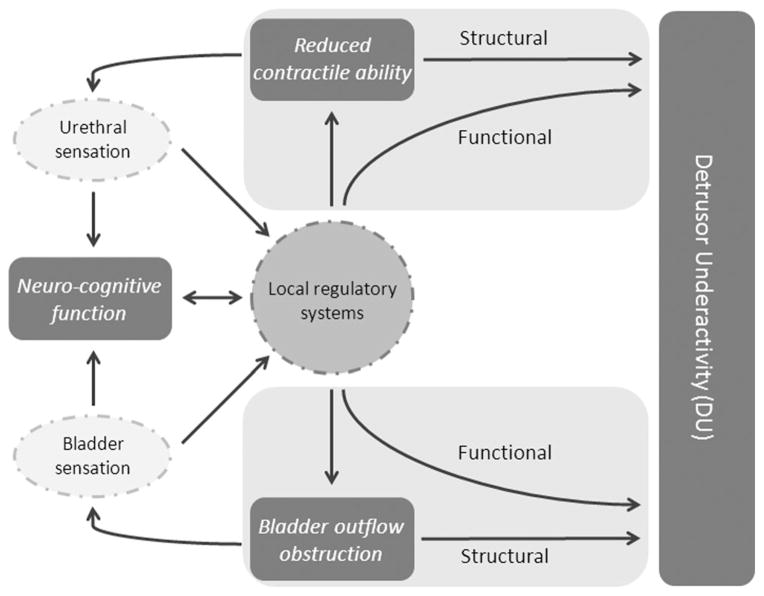

Anatomical (structural) or physiological (functional) changes may impair either detrusor contractile ability or urethral opening capacity. Efferent nerves may be damaged; the amount of muscle in the bladder wall reduced or replaced by connective tissue, or there may be a reduction in true contractility. In addition, structural bladder outlet obstruction can reduce effective voiding. When both bladder contractile function and the bladder outlet are adequate, an impairment of sensory nerves may also lead to inefficient voiding.

To void efficiently, a feed-forward mechanism by which urinary flow in the urethra helps to enhance and maintain adequate contractile function of the bladder, until the bladder is empty is required. Sensory information is fed back to the motor system at several levels of control between the end organ and brain cortex. These sensors themselves can be damaged, for example through an effect of ageing or ischaemia. In addition, impairment of innervation can lead to decreased information transfer via either the sensory or motor nerves. A functional disruption of higher central nervous regulatory systems can lead to functional abnormal voiding. This can occur as a result of disease induced deregulation (e.g., Parkinson’s or Alzheimer’s disease), ageing induced defects and psychological or psychiatric pathology.

Whether ageing related defects in these systems lead to inefficient emptying depends on the compensatory ability of mechanisms involved in voiding. To manage a dysfunction, the defect itself may be treated, but the compensatory capacity of another mechanism can also be improved. The choice of treatment may depend on the therapeutic effect required and the potential side-effects of the proposed treatment.

The most comprehensive approach to diagnose and treat voiding inefficiency in humans is first to study the pathophysiological alterations leading to impaired bladder emptying in humans. Animal models that mimic elements of derangements, as discussed above may be helpful to identify options that ameliorate these defects, or stimulate compensatory mechanisms and so define potentially treatable options in humans.

Since publication of the ICI-RS article in 2011 the topic of detrusor underactivity (DU) has received increasing research interest,2 with 54 articles retrievable by PubMed using DU/underactive bladder as search terms. However, few of these publications lead to better understanding of the complex pathophysiology underlying this urological entity.3–7 There are still many uncertainties with regard to the underactive bladder, particularly the role of ageing, altered sensory function, and the translational value of existing animal models.

AGEING: THE PRIMARY CAUSE OR A CONDITION NECESSARY FOR DEVELOPMENT OF DETRUSOR UNDERACTIVITY?

The prevalence of impaired bladder emptying is associated with increasing age and occurs in both men and women.8–10 This is manifest in the frequent finding of a raised post-void residual urinary volume in an otherwise asymptomatic older person11 and in association with other lower urinary tract diagnoses upon presentation to a clinician.12 Impaired bladder emptying has most often been described in association with detrusor overactivity, regardless of the presence of bladder outlet obstruction.13 Urodynamic data revealing impaired emptying function in the elderly are conflicting,14 and also are limited to those with symptoms, perhaps limiting the interpretation of age-associated pathophysiology. Histologically, older bladders differ from those in younger people, in that there is an age-associated accumulation of connective tissue and collagen, resulting in a reduction of the smooth muscle: collagen ratio,15 which may lead to a reduction of transmitted contractile force. At the level of the muscle cell, detrusor contractility is not reduced with ageing in those without detrusor overactivity or obstruction, unlike the diminution reported in older people with these conditions.16 The reduction of bladder sensory function reported in association with increasing age17 may also contribute to DU. Functional magnetic resonance imaging in asymptomatic older people found diminished response to bladder filling in the insula, an area of the brain responsible for mapping visceral sensations.18 The current state of the limited evidence suggests that a number of factors associated with ageing may, per se, predispose to impaired emptying and that it is likely that, for those unaffected older people, their compensatory capacity outweighs the drivers of impaired emptying.

THE ROLE OF ALTERED SENSORY FUNCTION IN DETRUSOR UNDERACTIVITY

Impaired bladder contractile ability has been traditionally regarded as a major aetiological factor of DU. However, in the elderly, decreased bladder sensations are associated with DU and suggest a more complex pathology. Because detrusor contraction force and duration are a result of efferent nerve activity in combination with an adequate contractile ability, which in turn is dependent on sensory input, there is the potential for impaired afferent function to cause DU.19 Structural and functional tissue changes accompanying ageing and particular diseases may result in altered bladder afferent function, with subsequent reflex impairment of voiding function.

The urothelium, detrusor muscle, interposed interstitial cells, and ganglia collectively form a mechano-sensitive sensor-transducer system which activates afferent nerve fibres.19 Abnormalities in each of these components could have an impact on LUT function by altering release of neurotransmitters, as well as the excitability of sensory fibres and the contractility of detrusor muscle in the urinary bladder. Furthermore, because many urothelial functions may be altered with age, defects in urothelial cells may contribute to age-related changes. Moreover, positive sensory feedback from urethral afferents, in response to flow, has been shown to augment detrusor pressure amplitude and duration, and is necessary for efficient voiding,20 thus urethral sensory disturbance could also lead to DU in specific patient categories.

In addition to the positive feedback mechanism described above, a defect in sensory function of the bladder itself may lead to delayed voiding and overdistention, again leading to damage of the sensors, denervation, or impaired muscle function.

WHAT IS THE VALUE OF CURRENT ANIMAL MODELS OF CONCOMITANT DISEASE?

The reason for developing animal models is usually to mimic part of a human pathology or a functional problem. Since the clinical problems in DU are in the voiding phase and involve “prolonged duration” and/or “reduced contractile strength,” it is worthwhile to concentrate on creating one or both in an animal. The value of such models is dependent on the question to be addressed: for example, to study the consequence of a lesion or artificial pathology on the voiding phase; or to test a drug intended to reverse a voiding problem. For the latter it is important that the functional parameters in the animal model may be reversed to warrant testing of a drug. Various models have been constructed and these are discussed with respect to the addition of information to our current knowledge on DU below. Particular attention is given to ageing, age-related comorbidity, obstruction models, and specific neurogenic models for DU.

Ageing Models

To study “healthy ageing,” animal models use the concept of a “healthspan” as an age range when an animal is generally healthy.21 Human lower urinary tract dysfunction, prevalent at an age >65 years should be reflected in laboratory animals. Biomarkers associated with an ageing phenotype appear in mice and rats >18–24 months and guinea-pigs when >30 months.22–24 In vivo, bladder contractile function may not diminish with age25 but compliance and/or micturition frequency increase or decrease.25–27 In vitro, contractility is either diminished or increased with age in both rats and mice.26,28–30 Muscle loss may,28 but not always increase with age: for example intravesical pressure at micturition actually increased with age in rats.30 Moreover, motor nerve density is preserved in rabbits.31 Afferent nerve density declines in ageing animals32; however, the age-related increase of urothelial transmitter release in the human bladder33 has not been reproduced in animal preparations.

Overall, there are conflicting data on bladder function and morphology in ageing animals. It is crucial to characterize individual ageing animal models, using comparable criteria, to determine if their phenotype mirrors that of the ageing human and there is clearly still work to be done in seeking the ideal model which stands up as an adequate specific model for this purpose.

Diabetic Bladder Dysfunction (DBD) Models

Recognition of high rates of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in both type 1 and type 2 diabetic patients led to development of the term diabetic bladder dysfunction (DBD) as an umbrella description for a group of clinical symptoms.34 DBD includes storage and voiding problems, as well as other less well-defined clinical phenotypes, such as decreased sensation and increased capacity. Portions of this spectrum of changes have been reported in other pathologies that result in LUTS such as bladder outlet obstruction, neurogenic bladder, and geriatric voiding dysfunction.35,36 Although no single study has yet reported the cumulative effects on patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, it has been estimated from multiple studies that DBD is among the most common and costly complications of diabetes mellitus, affecting 87% of patients.34

In type 1 diabetes models, DBD seems to follow a characteristic progression, resulting in different phenotypes of lower urinary tract dysfunction in early and late phases. Early stage diabetes (<9 weeks in rodents) causes detrusor overactivity in both in vivo (cystometry) and in vitro (organ-bath) studies. In the later stage (>12 weeks in rodents), the detrusor loses its ability to expel urine or respond to in vitro stimuli such as electrical field stimulations. Therefore, it has been hypothesized that the result of end-stage DBD is an atonic or underactive detrusor37 that is the result of long-term hyperglycaemia-related oxidative stress and polyuria.38,39 There is a growing body of evidence to indicate that oxidative stress and inflammation are independently associated with obesity and diabetes. Furthermore, oxidative stress appears to contribute to complications of these disorders that include detrusor overactivity and geriatric bladder dysfunction,40–42 it is plausible that the natural history of DBD could be replicated in other chronic conditions affecting the bladder such as obesity and ageing.

Obstruction and Bladder Overdistension Models

Bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) is a common precursor of LUTS in the ageing male population, leading to filling and/or voiding phase complaints.43 However, whether a patient develops a higher post-void residual or eventual urinary retention is not only dependent on the grade of BOO. Numerous in vitro and in vivo animal studies have reported the bladder’s response to acute or chronic BOO 44–48. Several in vitro studies have shown a consistent relationship between increased bladder mass and altered contractile responses in muscle strips in prolonged BOO in rat, rabbit and cat preparations.49–52 Some studies have even compared findings in animals to the human situation, mainly focusing on structural rather than functional changes.53,54

Current models mostly induce mechanical obstruction by placing a clip, ring, or suture around the urethra to induce partial BOO. While acute effects are seen in these models, the functional effects in partial BOO (pBOO) for longer times (>6 weeks in rat and rabbit, and >3 months in cats) seem to mimic the effects in human BOO relatively well. In these experimental conditions the bladder mass increases in proportion to the increase of bladder volume and the inability to empty completely. With experimentally-induced BOO in cats, deterioration of bladder function proceeded more slowly than in rats and rabbits and the functional and morphological state of a compensated bladder remain relatively stable52; this is also often seen in humans with BOO but occurs at a much slower rate. Thus pBOO models in rodents, rabbits, and cats can mimic some of the aspects of loss of contraction seen in DU. In these models reversibility of function after removal of the obstruction is often not seen. This is not a problem if one is interested in the developmental pathology of DU, but is if the model is to be used for drug-effect studies that might reverse obstruction.

Ischaemia/Oxidative Stress Models

The two main animal models to investigate in vitro oxidative damage are: direct bladder damage by hydrogen peroxide; or indirect induction via ischaemia followed by reperfusion.55 Atherosclerosis-induced chronic bladder ischaemia significantly reduces detrusor contractility of rabbit56 and rat bladders.57 A general problem in these models is that the severity of effects is difficult to titrate and establish, leading to large variability of results. In vitro induction of oxidative stress, whether or not caused by artificial obstruction, led to a significant decrease in contractility.55,58 Overall, in vitro as well as in vivo animal studies clearly show a correlation between oxidative stress and impaired contractility. One of the important remaining questions is to what extent reduction of oxidative stress can be utilized as a potential therapeutic target in humans.59,60

Neurogenic Animal Models

Besides age-related comorbidities, incomplete emptying is also common in patients with bladder dysfunction caused by specific neurological disease, including multiple sclerosis (0–40%),61 Parkinson’s disease (53%),62 and multiple system atrophy (52–67%).63 Several animal models have been designed to mimic specific neurogenic situations and relate these to altered contractility.3 DU can span a spectrum from slightly decreased ability to generate intravesical pressure (that may in turn be compensated for by increasing outlet-opening capability) to a bladder that cannot generate any pressure for emptying upon neural activation. A canine model of lower motor neuron injury has been developed, resulting in an atonic bladder.64 This spinal root transection model showed activation of different nerve tracts to the bladder after its reinnervation by transfer of the genitofemoral nerve,65 indicating that there is plasticity in the end organ following bladder reinnervation.

Although the neurogenic models mimic specific situations, experimental results may not be applied to a wider group of DU patients, however, some reinnervation paradigms have already been tested in experimental human studies,66 thus accentuating their importance and high translational value.

WHAT DATA DO WE NEED AND WHAT RESEARCH QUESTIONS SHOULD BE ADDRESSED IN THE FUTURE?

-

Development of study tools based on a system’s pathophysiological approach

Given that effective voiding is maintained via a complex balance between the compensatory capacity (or contractile reserve) of the bladder and the outlet opening capability of the bladder neck and urethra (Fig. 1), improvement of one or both compensatory and correctable mechanisms could potentially be used as a therapeutic target. More insight into the interplay of different mechanisms (Fig. 2) such as bladder and urethral sensation, urethral/bladder neck relaxation and detrusor contraction, all under neuro-cognitive control might give additional clues to explain ineffective bladder emptying.

Which clinical observations determine best detrusor compensatory capacity or infravesical relaxation capacity and might define patients at risk for DU?

How might the contributions of each factor be isolated and measured?

What is the role of bladder/urethral sensation and of neurocognitive regulation in DU?

-

Characterization of morphological and functional properties of isolated bladder wall samples

Research to evaluate structural bladder and urethral changes in humans with DU should lead to better understanding of its aetiology.

In vitro data from isolated human detrusor material should yield invaluable information about cell and tissue pathways that regulate detrusor contractility and urethral relaxation allowing exploration of the relationship between contractility and the clinical observation of impaired contractile function This may be related to confounding factors in in vitro preparations that influence contractile output, but unrelated to muscle contractility per se, including: altered connective tissue content; detrusor denervation and enhanced neurotransmitter secretions from other tissues, such as the mucosa.3,16,67 Moreover, factors other than changes to bladder wall tension (in principle true detrusor contractility) affect the ability of the bladder to raise intravesical pressure, including: outflow tract resistance; initial bladder volume; and bladder geometry.68

What structural bladder and urethral changes in humans are associated with the development of DU?

What is the relationship between morphological and functional properties of isolated bladder wall samples and resultant LUT function from bladders yielding those biopsy samples?

-

Correlation of in vitro and in vivo data

Likewise, such exploration of in vitro and in vivo human material should allow additional insight into the translational nature of existing animal models.

What is the relationship between in vitro data and in vivo function in animal models of DU?

-

Development of more comprehensive models

Currently, most animal models represent a specific disease state to explain DU, for example diabetes or BOO, therefore for every model a translational step to a comparable human conditions should be made.

Which comprehensive animal models can we develop based on clinical observations and pathophysiological considerations.

-

Longitudinal data; needed for defining risk groups and development of screening tools

In human DU multiple factors are most likely simultaneously involved. This multifactorial nature makes it challenging to define whether a drug, tested in experimental animals, will have a substantial effect in clinical urological practice. Therefore, determination of urodynamic or history-based indicators for DU is necessary for detection, diagnosis and follow-up after therapy. In addition, there is a need for longitudinal studies in LUTS patients to define the factors, which place patients at risk for developing DU.

What are the urodynamic or history-based indicators, associated with DU, which are required for detection, diagnosis and follow-up after therapy?

Are there specific pathological markers, which could allow definition of at risk groups?

Is there potential for a non-invasive screening tool to predict at risk patients?

Focus of future DU research Animal studies Human studies 1 Development of study tools based on a system’s pathophysiological approach ✓ ✓ 2 Characterization of morphological and functional properties of isolated bladder wall samples ✓ ✓ 3 Correlation of in vitro and in vivo data ✓ 4 Development of more comprehensive models ✓ 5 Longitudinal data; needed for defining risk groups and development of screening tools ✓

Fig. 1.

Schematic hypothetical relationship between obstruction and detrusor contractility as a function of age. The diagram shows an increase of obstruction and subsequent decrease of detrusor contractility. Whether or not a patient develops detrusor underactivity over time is dependent on the capacity to compensate by increasing detrusor contractility (detrusor contractile ability or “contractile reserve”) or alter bladder outflow relaxation (outlet opening capability). *Represents the rest compensatory capacity.

Fig. 2.

Complexity of the interplay between factors involved in bladder emptying and detrusor underactivity. Structural and/or functional changes may result from reduced ability of the bladder to contract or bladder outflow obstruction (BOO). Changes to sensory pathways and to neuro-cognitive function could affect either of these two major causative pathways.

Acknowledgments

Portions of the results on “neurogenic animal models” were supported by Award Number Portions R01NS070267 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none.

References

- 1.Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: Report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–78. doi: 10.1002/nau.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Koeveringe GA, Vahabi B, Andersson KE, et al. Detrusor underactivity: A plea for new approaches to a common bladder dysfunction. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:723–8. doi: 10.1002/nau.21097. Epub 2011/06/11. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young JS, Johnston L, Soubrane C, et al. The passive and active contractile properties of the neurogenic, underactive bladder. BJU Int. 2013;111:355–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sekido N, Jyoraku A, Okada H, et al. A novel animal model of underactive bladder: Analysis of lower urinary tract function in a rat lumbar canal stenosis model. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:1190–6. doi: 10.1002/nau.21255. Epub 2012/04/05. Eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Everaerts W, De Ridder D. Unravelling the underactive bladder: A role for TRPV4? BJU Int. 2013;111:353–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2012.11793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang HH, Kokiko-Cochran ON, Li K, et al. Bladder dysfunction changes from underactive to overactive after experimental traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 2013;240:57–63. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osman NI, Chapple CR, Abrams P, et al. Detrusor underactivity and the underactive bladder: A new clinical entity? A review of current terminology, definitions, epidemiology, aetiology, and diagnosis. Eur Urol. 2014;65:389–98. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cucchi A, Quaglini S, Rovereto B. Development of idiopathic detrusor underactivity in women: From isolated decrease in contraction velocity to obvious impairment of voiding function. Urology. 2008;71:844–8. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.11.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madersbacher S, Pycha A, Schatzl G, et al. The aging lower urinary tract: A comparative urodynamic study of men and women. Urology. 1998;51:206–12. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00616-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malone-Lee J, Wahedna I. Characterisation of detrusor contractile function in relation to old age. Br J Urol. 1993;72:873–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb16289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonde HV, Sejr T, Erdmann L, et al. Residual urine in 75-year-old men and women. A normative population study Scand. J Urol Nephrol. 1996;30:89–91. doi: 10.3109/00365599609180895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeong SJ, Kim HJ, Lee YJ, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of detrusor underactivity among elderly with lower urinary tract symptoms: A comparison between men and women. Korean J Urol. 2012;53:342–8. doi: 10.4111/kju.2012.53.5.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Resnick NM, Elbadawi AE, Yalla SV. Age and the lower urinary tract: What is normal? Neurourol Urodyn. 1995;14:577–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ameda K, Sullivan MP, Bae RJ, et al. Urodynamic characterization of nonobstructive voiding dysfunction in symptomatic elderly men. J Urol. 1999;162:142–6. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199907000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Susset JG, Servot-Viguier D, Lamy F, et al. Collagen in 155 human bladders. Invest Urol. 1978;16:204–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fry CH, Bayliss M, Young JS, et al. Influence of age and bladder dysfunction on the contractile properties of isolated human detrusor smooth muscle. BJU Int. 2011;108:E91–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collas DM, Malone-Lee JG. Age-associated changes in detrusor sensory function in women with lower urinary tract symptoms. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor dysfunct. 1996;7:24–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01895101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffiths D, Tadic SD, Schaefer W, et al. Cerebral control of the bladder in normal and urge-incontinent women. NeuroImage. 2007;37:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith PP. Aging and the underactive detrusor: A failure of activity or activation? Neurourol Urodyn. 2010;29:408–12. doi: 10.1002/nau.20765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shafik A, Shafik AA, El-Sibai O, et al. Role of positive urethrovesical feedback in vesical evacuation. The concept of a second micturition reflex: The urethrovesical reflex. World J Urol. 2003;21:167–70. doi: 10.1007/s00345-003-0340-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sprott RL. Introduction: Animal models of aging: Something old, something new. ILAR J. 2011;52:1–3. doi: 10.1093/ilar.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes BG, Hekimi S. A mild impairment of mitochondrial electron transport has sex-specific effects on lifespan and aging in mice. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26116. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haynes V, Traaseth NJ, Elfering S, et al. Nitration of specific tyrosines in FoF1 ATP synthase and activity loss in aging. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;298:E978–87. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00739.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xi M, Chase MH. The impact of age on the hypnotic effects of eszopiclone and zolpidem in the guinea pig. Psychopharmacology. 2009;205:107–17. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1520-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith PP, DeAngelis A, Kuchel GA. Detrusor expulsive strength is preserved, but responsiveness to bladder filling and urinary sensitivity is diminished in the aging mouse. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R577–86. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00508.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao W, Aboushwareb T, Turner C, et al. Impaired bladder function in aging male rats. J Urol. 2010;184:378–85. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lluel P, Palea S, Barras M, et al. Functional and morphological modifications of the urinary bladder in aging female rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2000;278:R964–72. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.4.R964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai HH, Boone TB, Thompson TC, et al. Using caveolin-1 knockout mouse to study impaired detrusor contractility and disrupted muscarinic activity in the aging bladder. Urology. 2007;69:407–11. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yono M, Latifpour J, Yoshida M, et al. Age-related alterations in the biochemical and functional properties of the bladder in type 2 diabetic GK rats. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2005;25:147–57. doi: 10.1080/10799890500210461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shenfeld OZ, Meir KS, Yutkin V, et al. Do atherosclerosis and chronic bladder ischemia really play a role in detrusor dysfunction of old age? Urology. 2005;65:181–4. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guven A, Mannikarottu A, Whitbeck C, et al. Effect of age on the response to short-term partial bladder outlet obstruction in the rabbit. BJU Int. 2007;100:930–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohammed HA, Santer RM. Distribution and changes with age of calcitonin gene-related peptide- and substance P-immunoreactive nerves of the rat urinary bladder and lumbosacral sensory neurons. Eur J Morphol. 2002;40:293–301. doi: 10.1076/ejom.40.5.293.28900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshida M, Inadome A, Maeda Y, et al. Non-neuronal cholinergic system in human bladder urothelium. Urology. 2006;67:425–30. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomez CS, Kanagarajah P, Gousse AE. Bladder dysfunction in patients with diabetes. Curr Urol Rep. 2011;12:419–26. doi: 10.1007/s11934-011-0214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gormley EA. Urologic complications of the neurogenic bladder. Urol Clin North Am. 2010;37:601–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gammack JK. Lower urinary tract symptoms. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26:249–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Daneshgari F, Liu G, Birder L, et al. Diabetic bladder dysfunction: Current translational knowledge. J Urol. 2009;182:S18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.08.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiao N, Wang Z, Huang Y, et al. Roles of polyuria and hyperglycemia in bladder dysfunction in diabetes. J Urol. 2013;189:1130–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Christ GJ, Hsieh Y, Zhao W, et al. Effects of streptozotocin-induced diabetes on bladder and erectile (dys)function in the same rat in vivo. BJU Int. 2006;97:1076–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calabrese V, Cornelius C, Leso V, et al. Oxidative stress, glutathione status, sirtuin and cellular stress response in type 2 diabetes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:729–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang YC, Chuang LM. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes: From molecular mechanism to clinical implication. Am J Transl Res. 2010;2:316–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Higdon JV, Frei B. Obesity and oxidative stress: A direct link to CVD? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:365–7. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000063608.43095.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soler R, Andersson KE, Chancellor MB, et al. Future direction in pharmacotherapy for non-neurogenic male lower urinary tract symptoms. Eur Urol. 2013;64:610–21. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buttyan R, Chen MW, Levin RM. Animal models of bladder outlet obstruction and molecular insights into the basis for the development of bladder dysfunction. Eur Urol. 1997;32:32–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nigro DA, Haugaard N, Wein AJ, et al. Metabolic basis for contractile dysfunction following chronic partial bladder outlet obstruction in rabbits. Mol cell Biochem. 1999;200:1–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1006973412237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rohrmann D, Levin RM, Duckett JW, et al. The decompensated detrusor I: The effects of bladder outlet obstruction on the use of intracellular calcium stores. J Urol. 1996;156:578–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zderic SA, Rohrmann D, Gong C, et al. The decompensated detrusor II: Evidence for loss of sarcoplasmic reticulum function after bladder outlet obstruction in the rabbit. J Urol. 1996;156:587–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tong-Long Lin A, Chen KK, Yang CH, et al. Recovery of microvascular blood perfusion and energy metabolism of the obstructed rabbit urinary bladder after relieving outlet obstruction. Eur Urol. 1998;34:448–53. doi: 10.1159/000019780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schroder A, Chichester P, Kogan BA, et al. Effect of chronic bladder outlet obstruction on blood flow of the rabbit bladder. J Urol. 2001;165:640–6. doi: 10.1097/00005392-200102000-00087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu Y, Shi B, Xu Z, et al. Are TGF-beta1 and bFGF correlated with bladder underactivity induced by bladder outlet obstruction? Urol Int. 2008;81:222–7. doi: 10.1159/000144066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levin RM, Schuler C, Leggett RE, et al. Partial outlet obstruction in rabbits: Duration versus severity. Int J Urol. 2013;20:107–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2012.03184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levin RM, Longhurst PA, Barasha B, et al. Studies on experimental bladder outlet obstruction in the cat: Long-term functional effects. J Urol. 1992;148:939–43. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36782-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Levin RM, Haugaard N, O’Connor L, et al. Obstructive response of human bladder to BPH vs. rabbit bladder response to partial outlet obstruction: A direct comparison. Neurourol Urodyn. 2000;19:609–29. doi: 10.1002/1520-6777(2000)19:5<609::aid-nau7>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elbadawi A, Yalla SV, Resnick NM. Structural basis of geriatric voiding dysfunction. IV. Bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 1993;150:1681–95. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35869-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malone L, Schuler C, Leggett RE, et al. The effect of in vitro oxidative stress on the female rabbit bladder contractile response and antioxidant levels. ISRN Urol. 2013;2013:639685. doi: 10.1155/2013/639685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azadzoi KM, Tarcan T, Siroky MB, et al. Atherosclerosis-induced chronic ischemia causes bladder fibrosis and non-compliance in the rabbit. J Urol. 1999;161:1626–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nomiya M, Yamaguchi O, Andersson KE, et al. The effect of atherosclerosis-induced chronic bladder ischemia on bladder function in the rat. Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:195–200. doi: 10.1002/nau.21073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nomiya M, Yamaguchi O, Akaihata H, et al. Progressive vascular damage may lead to bladder underactivity in rats. J Urol. 2014;191:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.10.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oka M, Fukui T, Ueda M, et al. Suppression of bladder oxidative stress and inflammation by a phytotherapeutic agent in a rat model of partial bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2009;182:382–90. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Toklu H, Alican I, Ercan F, et al. The beneficial effect of resveratrol on rat bladder contractility and oxidant damage following ischemia/reperfusion. Pharmacology. 2006;78:44–50. doi: 10.1159/000095176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Seze M, Ruffion A, Denys P, et al. The neurogenic bladder in multiple sclerosis: Review of the literature and proposal of management guidelines. Mult Scler. 2007;13:915–28. doi: 10.1177/1352458506075651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sakakibara R, Uchiyama T, Yamanishi T, et al. Bladder and bowel dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2008;115:443–60. doi: 10.1007/s00702-007-0855-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bloch F, Pichon B, Bonnet AM, et al. Urodynamic analysis in multiple system atrophy: Characterisation of detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia. J Neurol. 2010;257:1986–91. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5645-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ruggieri MR, Braverman AS, D’Andrea L, et al. Functional reinnervation of the canine bladder after spinal root transection and immediate end-on-end repair. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23:1125–36. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.23.1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ruggieri MR, Braverman AS, D’Andrea L, et al. Functional reinnervation of the canine bladder after spinal root transection and immediate somatic nerve transfer. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25:214–24. doi: 10.1089/neu.2007.0328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xiao CG. Reinnervation for neurogenic bladder: Historic review and introduction of a somatic-autonomic reflex pathway procedure for patients with spinal cord injury or spina bifida. Eur Urol. 2006;49:22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.10.004. discussion 8–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumar V, Chapple CR, Rosario D, et al. In vitro release of adenosine triphosphate from the urothelium of human bladders with detrusor overactivity, both neurogenic and idiopathic. Eur Urol. 2010;57:1087–92. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bross S, Braun PM, Michel MS, et al. Bladder wall tension during physiological voiding and in patients with an unstable detrusor or bladder outlet obstruction. BJU Int. 2003;92:584–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]