Abstract

Antibody levels to Clostridium difficile toxin A (TcdA), but not toxin B (TcdB), have been found to determine risk of C. difficile infection (CDI). Historically, TcdA was thought to be the key virulence factor; however the importance of TcdB in disease is now established. We re-evaluated the role of antibodies to TcdA and TcdB in determining patient susceptibility to CDI in two separate patient cohorts. In contrast to earlier studies, we find that CDI patients have lower pre-existing IgA titres to TcdB, but not TcdA, when compared to control patients. Our findings suggest that mucosal immunity to TcdB may be important in the early stages of infection and identifies a possible target for preventing CDI progression.

Keywords: Clostridium difficile, toxin B (TcdB), toxin A (TcdA), Humoral immune response, case-control study

1. Introduction

Clostridium difficile is a common cause of nosocomial diarrhea (1). In epidemic settings around 5% of older hospitalized patients develop symptomatic C. difficile infection (CDI); however, this represents only a minority of patients who are infected (2). The severity of symptomatic CDI ranges from a self-limited diarrheal illness to fulminant colitis and death (3). Following successful treatment, around one quarter of patients suffer recurrence of symptoms, either caused by relapse of the original infection or reinfection with a new strain (4)(5). At each stage in the disease process humoral immune responses, in particular to C. difficile toxins, may contribute to disease susceptibility. Landmark studies performed in the 1990s indicated antibody responses directed against toxin A (TcdA), but not toxin B (TcdB), were associated with protection from disease and from recurrence (6)(7). Since these studies were performed the nature of CDI has changed markedly with the advent of ‘hypervirulent’ ribotype 027 (North American Pulse Type 1) strains which are associated with greater mortality and a higher rate of disease recurrence (1). Furthermore, the importance of TcdA in disease pathogenesis has been called into question by the demonstration that TcdB but not TcdA is necessary for full virulence of C. difficile in experimental models of infection (8), although this was not confirmed by other groups (9). In the context of these developments we reassessed the relationship between antibody responses to C. difficile toxins in the early stages of infection in determining susceptibility to CDI among hospitalized patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting and patients

The Royal Sussex County Hospital, Brighton, UK is an 800-bed acute general hospital on the south coast of England. Case patients were recruited within 72 hours of testing positive for TcdA or TcdB (using Premier TcdA and TcdB ELISA [Meridian Bioscience, USA]) and had passed >2 liquid stools in the 24 hour period before assessment. Control patients were diarrhea-free inpatients in receipt of antibiotics. All controls were confirmed C. difficile spore negative by culture using an alcohol shock method. Faecal samples were diluted 1:10 in a cryopreservative broth (Brain heart infusion broth [Oxoid, UK]) and an aliquot of the 1:10 dilution of faeces was mixed with an equal volume of alcohol and left for 30 minutes before being sub-cultured on to reinforced clostridia medium (E&O, UK) and incubated for 48 hours anaerobically at 37°C (10). Written consent was required for participation in the study. Ethics approval was provided by the South East Ethics Committee (reference 09/H1102/63).

The University of Michigan Hospital is a 930-bed, tertiary care hospital in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Cases and controls were identified from hospitalized adults who were tested for CDI at the discretion of their treating physician. Cases that tested positive for C. difficile toxins (C. DIFF QUIK CHEK COMPLETE® test, Techlab, Inc., USA) were confirmed by culture (by alcohol shock and anaerobic culture on taurocholate-cycloserine-cefoxitin-fructose agar at 37°C) and PCR, with no previous history of CDI recurrence. An equal number of age and gender matched controls with C. difficile toxin negative diarrhea were selected and confirmed as C. difficile negative by culture. Controls had no previous history of CDI. All serum samples were sent to Brighton and processed under the same laboratory conditions as the Brighton samples. This work was carried out as part of the Enteric Research Integrative Network (ERIN) project, University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approval number HUM00033286.

2.2. C. difficile toxin antibody ELISA

Recombinant C. difficile TcdA and TcdB (strain VIP10463) were expressed in Bacillus megaterium as C-terminally 6xHis-tagged proteins and purified by nickel affinity chromatography as published previously (11)(12). High absorbance ELISA plates were coated with 50μL of toxin (1μg/mL), incubated at 4°C overnight, washed and blocked with bovine serum albumin in PBS and 0.05% Tween 20 (200μl) prior to use. Serial dilutions of serum (1:25 to 1:1600) in blocking buffer were plated in duplicate, incubated and probed with goat-antihuman immunoglobulin horse radish peroxidase conjugate (Serotec, UK). Antibody binding was detected using O-phenylenediaminedihydro-chloride in citrate buffer, stopped with 10% hydrochloric acid and colour change read at 490 nm using mQuant Plate Reader (BioTek Instruments, USA). The background signal for uncoated plates was subtracted for each sample. Serial dilutions of pooled intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG, Viagam Liquid®, Bioproducts Laboratory, UK) were used to construct a standard curve for each plate. The cut-off level selected for defining a positive test sample was a signal greater than 1:1600 IVIG for TcdB and 1:3200 IVIG for TcdA. Pentaglobin (Biotest, UK) at a dilution of 1:800 was used to standardise the IgM ELISA, colostrum (Bioscience, UK) at a dilution of 1:1600 for the IgA ELISA and IVIG at a dilution of 1:1600 for the IgG ELISA. For all analyses, samples negative at the detection limit of the assay (1:25) were assigned an arbitrary value of 1:12.5.

To test the specificity of differences in antibody responses to C. difficile toxins between cases and controls we also assessed antibody responses to tetanus toxin (Sigma, UK) by ELISA performed in an identical manner.

2.3. Neutralisation Assay

A commercial assay kit (Diagnostics Hybrid, USA) was used to confirm the specificity and functionality of antibodies in serum. Human Foreskin Fibroblast (HFF) cells in shell-vials were thawed from −80°C using a heat block at 37°C for 4 minutes. The HFF cells were incubated with TcdB (10pg/mL) alone and in combination with serum at a dilution of 1:20 at 37°C overnight. An inverted light microscope (Axiovert 25 fluorescent microscope, Zeiss, UK) was used to look for evidence of cell rounding or neutralisation at 16 hours.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All data was analysed using GraphPad Prism™ (Graphpad Software, USA) and SPSS version 20 (IBM®, UK). Continuous variables were compared by t-test and categorical variables using Fisher’s exact test with p<0.05 used as a cut-off for statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Patient demographics

Serum samples were available for 20 newly diagnosed cases of CDI and 18 control patients recruited in Brighton and 20 newly diagnosed cases of CDI and 20 control patients recruited in Michigan (Table 1). Within both cohorts, case and control patients were of similar age and gender mix. Patients with CDI recruited to the study in Brighton were significantly older (median age 85.0 years, interquartile range [IQR] 65.0–88.0) than CDI patients from Michigan (median age 58.5 years IQR 49.0–66.5, p=0.002). Laboratory markers of inflammation and renal function were similar for cases and controls recruited in both Brighton and Michigan although serum albumin was lower in cases than controls recruited in Brighton (33 g/dL IQR 28–37 vs. 39 g/dL IQR 37–41, p=0.004). Two cases recruited in Brighton died (224 days and 21 days after CDI diagnosis respectively and neither as a result of their CDI) and five cases recruited in Michigan were admitted to the intensive care unit. One of the Michigan cases subsequently required a colectomy to treat CDI and one died (unrelated to CDI).

Table 1. Demographic and laboratory data for CDI case and control patients recruited to the study in Brighton and Michigan.

Median values and inter-quartile ranges (IQR) are given for laboratory parmeters. For the purpose of analysis all blood results were converted into units used in Brighton which are shown in the table. Normal ranges in Brighton laboratory: white cell count (4–11 109/L), C-reactive protein (<5 mg/L), urea (1.7–8.3 mmol/L), creatinine (62–106 μmol/L) and albumin (35–52 g/L). Complications were defined as colectomy, admission to Intensive care and death.

| Brighton | Michigan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | p | Cases | Controls | p | |

| n | 20 | 18 | - | 20 | 20 | - |

| Age (years) | 85.0 (65–88) | 77.5 (65.8–81.8) | p=0.39 | 58.5 (50–66) | 61.0 (51.5–66) | p=0.84 |

| Male gender (%) | 11 (55) | 12 (67) | p=0.39 | 12 (60) | 12 (60) | - |

| White cell count 109/L (IQR) | 11 (7–12) | 13 (9–15.5) | p=0.25 | 5 (4–11) | 5 (2.5–11.5) | p=0.78 |

| C-reactive protein mg/L (IQR) | 48 (15.6–91.6) | 72.5 (23.3–144.3) | p=0.31 | 60 (50–100) | n/a | - |

| Urea mmol/L (IQR) | 6 (4–8) | 7 (6–8) | p=0.43 | 6.2 (2.9–12) | 8 (4.5–10.4) | p=0.27 |

| Creatinine μmol/L (IQR) | 78 (64–127) | 80 (70.5–104.5) | p=0.92 | 88.4 (61.9–154.7) | 66.3 (57.5–88.4) | p=0.08 |

| Albumin g/L (IQR) | 33 (28–37) | 39 (37–41) | p=0.004* | 29.5 (27–34.5) | 34 (30–36) | p=0.19 |

| Complications | 2 | 0 | p=0.17 | 5 | 3 | p=0.43 |

3.2. Total antibody responses to TcdA and TcdB

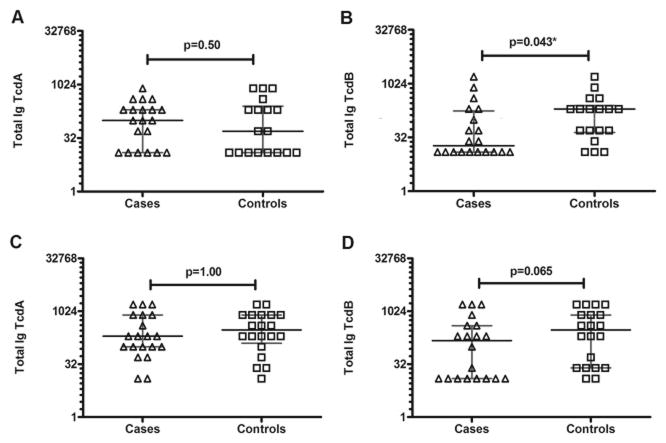

Comparing antibody responses among patients recruited in Brighton (Figure 1A and B), median total antibody titre against TcdA was similar among case and control patients (1:100 95% confidence interval [CI] 1:12.5–1:200 vs. control 1:50 95% CI 1:12.5–1:200). In contrast, median antibody titres against TcdB were three-fold lower in cases than controls (1:18.75 95% CI 1:12.5–1:100 vs. 1:200 95% CI 1:50–1:200). Fewer case than control patients had an antibody titre above the detection limit of the assay (10/20 cases [50%] vs. 15/18 controls [83%], p=0.043).

Figure 1. Total antibody titres to C. difficile TcdA and TcdB.

Antibody titres to TcdA and TcdB were measured by ELISA. For patients recruited in both Brighton and Michigan, case patients are represented as triangles and control patients as squares. Titres are expressed as dilutions using a logarithmic 2 scale along the y axis. All p-values were obtained using Fisher’s exact test. Median titres are shown as black horizontal lines and error bars are shown in grey. A and B. Total antibody titres (IgG, IgA and IgM) for patients recruited in Brighton. A significant difference was noted between cases and controls for TcdB (p=0.043) that was not observed for TcdA (p=0.50). C and D. Total antibody titres (IgG, IgA and IgM) for patients recruited in Michigan. A similar trend was observed in this cohort, with no significant difference in TcdA (p=1.00) and a difference in TcdB although this did not reach significance (p=0.065)

Among patients recruited in Michigan (Figure 1C and D) the same trend occurred with only 12/20 cases (60%) vs. 18/20 (90%) controls having antibody titres against TcdB above the detection limit of the assay, although this did not reach statistical significance (p=0.065). Antibody levels to TcdB were lower in cases than controls (1:150 95% CI 1:12.5–1:400 vs. 1:200 95% CI 1:25–1:800) whereas, antibodies to TcdA were again similar between cases and controls (1:200 95% CI 1:100–1:800 vs. 1:300 95% CI 1:00–1:800). This difference was less marked than in the Brighton samples and in fact the Brighton cases had a two-fold lower titre of antibodies to TcdB than the Michigan cases (1:18.75 95% CI 1:12.5–1:100 vs. 1:150 95% CI 1:12.5–1:400).

Antibody titres to tetanus toxin were also similar when comparing case and control patients from both Brighton and Michigan (data not shown).

3.3. Antibody class specific response

Samples from patients recruited in Brighton were tested for antibody-class specific responses to TcdB (Figure 2). While no differences could be detected in the IgG or IgM antibody titre with only a minority of cases and controls having levels above the detection limit of the assay, detectable IgA responses to TcdB were only present in 7/20 cases (35%) compared with 13/18 controls (72%) (p=0.028).

Figure 2. Antibody class specific responses to C. difficile TcdB.

Serum samples from 20 newly diagnosed CDI cases and 18 age-matched control patients recruited in Brighton were tested to establish if a class-specific antibody response to TcdB was present. Titres are expressed as dilutions using a logarithmic 2 scale along the y axis. All p values were obtained using Fisher’s exact test. Median titres are shown as black horizontal lines and error bars are shown in grey. Case patients are represented as triangles and control patients as squares. A. IgM response B. IgA response C. IgG response. Pentaglobin (1:800) was used to standardise the IgM assay, colostrum (1:1,600) the IgA assay and IVIG (1:1,600) the IgG assay.

3.4. Neutralisation

The ability of case and control patient serum to neutralise TcdB cytotoxicity was assessed for patients recruited in Brighton. Only two cases demonstrated neutralisation of TcdB at a dilution of 1:20 (data not shown).

4. Discussion

The majority of healthy adults have detectable antibodies to C. difficile TcdA and TcdB in their serum that are thought to arise from colonisation in infancy (13)(14). Research addressing the role of humoral immune responses in susceptibility to C. difficile has focused on responses to TcdA since in animal models of infection TcdA alone can evoke the symptoms of disease (15). Most notably, Kyne et al. reported in 2000 that a low IgG titre to TcdA, but not TcdB, at the time of infection is associated with development of symptomatic disease (6). More recently, the same group demonstrated an association between median IgG titres to TcdA and 30 day all-cause mortality (16) Several studies have also looked at antibody responses following infection and demonstrated protection against recurrence associated with antibody responses to TcdA, TcdB and several non-toxin antigens (Cwp66, Cwp84, FliC, FliD and the surface layer proteins) (7)(17)(18).

However, while virulent strains of C. difficile that lack the tcdA gene are now well described, the tcdB gene appears to be present in all reported virulent strains and studies using isogenic C. difficile mutants have demonstrated that TcdB is required for full virulence (8)(19).

The aim of the present work was to reassess the role of serum antibody titres against TcdA and TcdB, in the early stages of infection, in determining patient susceptibility to CDI.

All patients were sampled within 72 hours of CDI diagnosis. Given that the incubation period of C. difficile is also around 72 hours, the antibody titres we have measured represent pre-existing immunity rather than the antibody response to the current infection (20). In contrast to previous studies, our data demonstrate a difference between CDI cases and controls in total antibody titre to TcdB but not to TcdA. Crucially, this same effect is apparent in two sets of cases and controls recruited at different centres in different countries and using differently defined control patients. In Brighton, control patients were diarrhea-free elderly hospitalized patients and in Michigan, the control patients had C. difficile negative diarrhea. Asymptomatic carriage has been associated with protection from disease progression and therefore all controls were confirmed C. difficile negative by culture.

Although lower titres of antibody to TcdB were found in cases at both locations this difference was less marked in patients recruited in Michigan. This may be explained by the fact that these patients were on average 20 years younger than those recruited in Brighton, which in turn is consistent with the fact that patients with C. difficile in the USA are generally younger than in the UK reflecting differences in the average age of hospitalized patients (21)(22). This may be explained due to immunosenescence, which is the process by which the immune system undergoes age-related change. Although early observations suggested that a decline in immunity affected all components of the immune system in an indiscriminate way, it is now thought a remodelling affect occurs and the greatest changes take place in the adaptive immune response (23). As these differences preclude combined analysis of the patient groups but our repetition of the fundemental observation in both comparisons is compelling.

In cases with lower antibody responses to TcdB, serum IgA levels were significantly lower than controls, which might reflect the importance of mucosal immunity in the early stages of CDI. Correlation between serum IgA and secretory IgA (sIgA) at the gastrointestinal mucosa has been shown in animal models, although the strength of antibody response may vary dependent on the antigen (24). In the clinical setting, intestinal secretions obtained by colonic lavage were measured for TcdA-specific sIgA and found to display a similar pattern of antibody response to serum antitoxin responses (25). Therefore, lower levels of serum IgA in the current study may reflect a failed local mucosal immune response to TcdB-mediated intestinal inflammation or represent particularly high levels of TcdB locally that could neutralise IgA in the colon.

It is notable that C. difficile cases recruited to the study had mild disease as evidenced by the fact that their average C-reactive protein levels, white cell counts and renal function test results were no different from control cases. This is explained by the fact that written consent was required for participation in the study and thus severely ill patients could not be recruited.

Our study has several notable limitations. First, ribotyping data for isolates was generally not available. We are unable to assess how the role of immune responses varies with infecting ribotype. However, ribotype 027 strains were prevalent at both sites during the time patients were recruited to the study (26)(27). Second, it is possible that antibody levels measured in our ELISA using recombinant TcdB from strain VPI10463 do not reflect antibody levels against the infecting strain TcdB. Marked strain differences are now known to exist in TcdB sequence and function (28). Recent work by Lanis et al. showed the historic VPI10463 strain and the epidemic 027 strain to differ by 11 epitopes within the TcdB binding region known as the carboxy terminal domain binding (29). Such antigenic variation in TcdB may contribute to the increased virulence of certain strains and is in keeping with our data suggesting that acquired immunity may not provide cross-protection between different strains.

We performed a neutralisation cytotoxicity assay to establish the functionality of antibodies detected by ELISA and it was surprising that only two cases demonstrated neutralisation of TcdB. The disparity between antibody titre and functionality might be explained by the high sensitivity of the assay to cytotoxicity and the sensitivity of the ELISA to detect polyclonal antibody responses which may not necessarily be functional. Previous studies have also demonstrated neutralisation of toxicity by sera in a minority of patients. For example, Johnson et al. found only 1/18 sera tested in the early stage of CDI was able to neutralise antibodies to TcdA compared to 5/14 convalescent sera, suggesting pre-existing antibodies may not be capable of neutralisation. In addition, the presence of neutralising antibodies were found to be independent of the clinical course of disease (25).

5. Conclusion

Early in the course of C. difficile infection (<72 hours) low IgA titres to C. difficile TcdB, but not TcdA are associated with susceptibility to disease. Our findings suggest that mucosal immunity to TcdB may be important in the early stages of infection and identifies a possible target for preventing CDI progression. However, given the antigenic variation of TcdB between different strains, the importance of measured antibody responses should be expected to change as different strain types circulate.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Freeman J, Bauer MP, Baines SD, Corver J, Fawley WN, Goorhuis B, et al. The Changing Epidemiology of Clostridium difficile Infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010 Jul 1;23(3):529–49. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00082-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riggs MM, Sethi AK, Zabarsky TF, Eckstein EC, Jump RL, Donskey CJ. Asymptomatic carriers are a potential source for transmission of epidemic and nonepidemic Clostridium difficile strains among long-term care facility residents. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(8):992–8. doi: 10.1086/521854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett JG. Clinical practice. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(5):334–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp011603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eyre DW, Walker AS, Griffiths D, Wilcox MH, Wyllie DH, Dingle KE, et al. Clostridium difficile Mixed Infection and Reinfection. J Clin Microbiol. 2012 Jan;50(1):142–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05177-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eyre DW, Walker AS, Wyllie D, Dingle KE, Griffiths D, Finney J, et al. Predictors of first recurrence of Clostridium difficile infection: implications for initial management. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2012 Aug;55( Suppl 2):S77–87. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyne L, Warny M, Qamar A, Kelly CP. Asymptomatic carriage of Clostridium difficile and serum levels of IgG antibody against toxin A. N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 10;342(6):390–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kyne L, Warny M, Qamar A, Kelly CP. Association between antibody response to toxin A and protection against recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Lancet. 2001 Jan 20;357(9251):189–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03592-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyras D, O’Connor JR, Howarth PM, Sambol SP, Carter GP, Phumoonna T, et al. Toxin B is essential for virulence of Clostridium difficile. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature07822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuehne SA, Cartman ST, Heap JT, Kelly ML, Cockayne A, Minton NP. The role of toxin A and toxin B in Clostridium difficile infection. Nature. 2010 Oct 7;467(7316):711–3. doi: 10.1038/nature09397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Health Protection Agency B 10 - Processing of Faeces for Clostridium difficile. http://www.hpa.org.uk/ProductsServices/MicrobiologyPathology/UKStandardsForMicrobiologyInvestigations.

- 11.Yang G, Zhou B, Wang J, He X, Sun X, Nie W, et al. Expression of recombinant Clostridium difficile toxin A and B in Bacillus megaterium. BMC Microbiol. 2008 Nov 6;8:192. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guttenberg G, Papatheodorou P, Genisyuerek S, Lü W, Jank T, Einsle O, et al. Inositol hexakisphosphate-dependent processing of Clostridium sordellii lethal toxin and Clostridium novyi alpha-toxin. J Biol Chem. 2011 Apr 29;286(17):14779–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.200691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bacon AE, III, Fekety R. Immunoglobulin G directed against toxins A and B of Clostridium difficile in the general population and patients with antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1994 Apr;18(4):205–9. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viscidi R, Laughon BE, Yolken R, Bo-Linn P, Moench T, Ryder RW, et al. Serum Antibody Response to Toxins A and B of Clostridium difficile. J Infect Dis. 1983 Jul;148(1):93–100. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyerly DM, Saum KE, MacDonald DK, Wilkins TD. Effects of Clostridium difficile toxins given intragastrically to animals. Infect Immun. 1985 Feb;47(2):349–52. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.2.349-352.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solomon K, Martin AJ, O’Donoghue C, Chen X, Fenelon L, Fanning S, et al. Mortality in patients with Clostridium difficile infection correlates with host pro-inflammatory and humoral immune responses. J Med Microbiol. 2013 Sep;62(Pt 9):1453–60. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.058479-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leav BA, Blair B, Leney M, Knauber M, Reilly C, Lowy I, et al. Serum anti-toxin B antibody correlates with protection from recurrent Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) Vaccine. 2010 Jan 22;28(4):965–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Drudy D, Calabi E, Kyne L, Sougioultzis S, Kelly E, Fairweather N, et al. Human antibody response to surface layer proteins in Clostridium difficile infection. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004 Jul 1;41(3):237–42. doi: 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drudy D, Fanning S, Kyne L. Toxin A-negative, toxin B-positive Clostridium difficile. Int J Infect Dis IJID Off Publ Int Soc Infect Dis. 2007 Jan;11(1):5–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFarland LV, Mulligan ME, Kwok RY, Stamm WE. Nosocomial acquisition of Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(4):204–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901263200402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elixhauser ALJ. Clostridium difficile infections(CDI) in Hospital Stays 2009. 2012 Jan; [Internet] Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb124.pdf. [PubMed]

- 22.Health protection agency & Department of Health. Clostridium difficile infection: how to deal with the problem. 2009 http://www.dh.gov.uk/en.

- 23.Franceschi C, Bonafè M, Valensin S. Human immunosenescence: the prevailing of innate immunity, the failing of clonotypic immunity, and the filling of immunological space. Vaccine. 2000 Feb 25;18(16):1717–20. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00513-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Externest D, Meckelein B, Schmidt MA, Frey A. Correlations between Antibody Immune Responses at Different Mucosal Effector Sites Are Controlled by Antigen Type and Dosage. Infect Immun. 2000 Jul;68(7):3830–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.3830-3839.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson S, Gerding DN, Janoff EN. Systemic and mucosal antibody responses to toxin A in patients infected with Clostridium difficile. J Infect Dis. 1992 Dec;166(6):1287–94. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.6.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson V, Cheek L, Satta G, Walker-Bone K, Cubbon M, Citron D, et al. Predictors of death after Clostridium difficile infection: a report on 128 strain-typed cases from a teaching hospital in the United Kingdom. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2010 Jun 15;50(12):e77–81. doi: 10.1086/653012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walk ST, Micic D, Jain R, Lo ES, Trivedi I, Liu EW, et al. Clostridium difficile Ribotype Does Not Predict Severe Infection. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2012 Dec;55(12):1661–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lanis JM, Barua S, Ballard JD. Variations in TcdB Activity and the Hypervirulence of Emerging Strains of Clostridium difficile. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(8):e1001061. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lanis JM, Heinlen LD, James JA, Ballard JD. Clostridium difficile 027/BI/NAP1 Encodes a Hypertoxic and Antigenically Variable Form of TcdB. PLoS Pathog. 2013 Aug 1;9(8):e1003523. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]