Abstract

Purpose

Estrogens play important roles in the pathogenesis and progression of breast cancer as well as estrogen-related diseases. Aromatase is a key enzyme in the rate-limiting step of estrogen production, in which its inhibition is one strategy for controlling estrogen levels to improve prognosis of estrogen-related cancers and diseases. Herein, a series of metal (Mn, Cu, and Ni) complexes of 8-hydroxyquinoline (8HQ) and uracil derivatives (4–9) were investigated for their aromatase inhibitory and cytotoxic activities.

Methods

The aromatase inhibition assay was performed according to a Gentest™ kit using CYP19 enzyme, wherein ketoconazole and letrozole were used as reference drugs. The cytotoxicity was tested on normal embryonic lung cells (MRC-5) using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay.

Results

Only Cu complexes (6 and 9) exhibited aromatase inhibitory effect with IC50 0.30 and 1.7 μM, respectively. Cytotoxicity test against MRC-5 cells showed that Mn and Cu complexes (5 and 6), as well as free ligand 8HQ, exhibited activity with IC50 range 0.74–6.27 μM.

Conclusion

Cu complexes (6 and 9) were found to act as a novel class of aromatase inhibitor. Our findings suggest that these 8HQ–Cu–uracil complexes are promising agents that could be potentially developed as a selective anticancer agent for breast cancer and other estrogen-related diseases.

Keywords: aromatase inhibitor, anticancer, metal-based compound

Introduction

Estrogens are well known as steroidal sex hormones. They not only play roles in the development and maintenance of the female reproductive system,1 but also take part in the regulation of many physiological processes.2–7

Estrogens are synthesized from cholesterol precursors8 in a multistep process facilitated by different enzymes.8 The last conversion process of C19 steroid (ie, androstenedione or testosterone) into the C18 steroid (ie, estrone or estradiol) by aromatization is considered to be the rate-limiting step of estrogen production.8 This key step is facilitated by the cytochrome P450 complex.9–13 Abnormal estrogen productions have been found to give rise to diseases and complications. Decreased level of estrogens was found to be involved with age-related conditions.2,14 Moreover, estrogens facilitate the growth of certain estrogen-dependent cancers such as breast15,16 and endometrial cancer.17–19

The treatment of breast cancer is multimodal,20 in which endocrine therapy is one of the possible approaches.9 Aromatase inhibition is considered a promising approach to decreasing the amount of estrogen production.1 Recently, aromatase inhibitors have been developed and used as anti-breast cancer agents with preferable treatment outcomes in postmenopausal women.21

Aromatase inhibitors can be classified into two classes based on their chemical structures and mechanism of action.9 Steroidal aromatase inhibitors competitively and covalently bind to aromatase enzyme in an irreversible fashion.22 Non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors contain azoles as the privileged structure1 for coordinating with heme iron (Fe) atom of aromatase enzyme leading to reversible enzyme inhibition.23 Moreover, antifungal agents containing the aza-heterocycle have been shown to afford aromatase inhibitory activity.24–27 Such a finding indicates the significance of a heterocyclic compound bearing the N-atom as a potential aromatase inhibitor.9

On the basis of existing literature, other classes of N-heterocyclic compounds, such as quinoline and pyrimidine, have drawn considerable interest. For example, 8-hydroxyquinoline (8HQ) is a quinoline derivative with potent molecular recognition and coordinating properties to metals.28 It is widely used as a metal chelator as well as for analytical and separation purposes.28 Recently, the anticancer activity of 8HQ-based compounds has been reported.29–33 Moreover, 8HQ and its derivatives exhibit a diverse range of biological activities, such as anti-neurodegenerative,34,35 antimicrobial,36–39 antimalarial,40–42 antioxidant,30,34 anti-inflammatory,43 and anticancer activities.44

Uracil derivatives are widely known for their anticancer properties. For example, 5-fluorouracil is a fluorinated uracil analog with anticancer activity against a wide range of cancers,45,46 such as head and neck,47,48 gastrointestinal,49,50 and breast cancer.51–53 Recently, 5-fluorouracil has been reported to be one of the most prescribed anticancer drugs.54

Transition metal ions play vital roles in many biological processes. They exist in multiple valence and oxidation states,55 which allows them to readily participate in electron transfer reactions and interact with negatively charged molecules.55 Transition metal complexes have been reported and used as anticancer agents.56,57 In this regard, many beneficial effects of metal complexation have been achieved. For example, metal ions can act as chaperones in order to deliver active ligands to target sites in a selective manner. Metal complexation has been shown to improve pharmacokinetic properties such as size, charge, and lipophilicity as well as minimize toxicity.58 It has also been reported that metal complexes can mimic the activity of enzymes such as superoxide dismutase.58–61

In efforts to increase the cancer survival rate, attention has been focused in recent years on multitasking drugs.62 Such multitasking drugs are developed by combining drugs in order to improve their efficiency and minimize toxicity. This strategy aims to achieve synergistic effects exerted by each drug as well as to improve drug delivery properties by controlling the lipophilicity and size of the drug.62

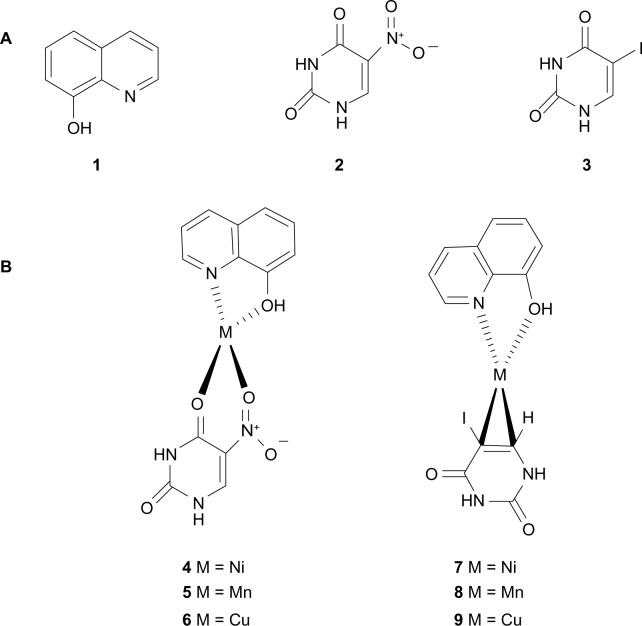

According to these principles of searching for novel aromatase inhibitors, this study employed 8HQ (1) and uracil derivatives including 5-nitrouracil (5Nu [2]) and 5-iodouracil (5Iu [3]) as ligands for the synthesis of mixed-ligand metal complexes 4–9 (Figure 1) that were subsequently tested for their aromatase inhibitory activity and cytotoxicity.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of ligands (1–3) (A) and metal complexes (4–9) (B).

Material and methods

Reagents for cell culture and assay were the following: Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum from JR Scientific Inc., Woodland, CA, USA; penicillin–streptomycin and 3(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) from Sigma-Aldrich Co (St Louis, MO, USA); and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) from EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA. CYP19 (a recombinant human aromatase) and O-benzyl fluorescein benzyl ester (DBF) were supplied with the BD Gentest™ kit from BD Biosciences-Discovery Labware, Woburn, MA, USA.

Tested compounds

Mixed-ligand metal complexes (4–9) were synthesized according to a previously described method30 using 1:1:1 molar ratio of 8HQ:M:5Nu (or 5Iu), where M = Ni, Mn, and Cu. The reaction was carried out in boiling methanol. Products were collected by filtration and washed four to five times with cold methanol. The compounds were confirmed by their infrared spectra, magnetic moment, and melting points.

Infrared spectra were obtained on a Perkin Elmer Spectrum System 2000 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Perkin Elmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Magnetic moment was obtained with an MK 1 Magnetic Susceptibility Balance (serial 15257; Sherwood Scientific, Cambridge, UK). Melting points were determined on a Griffin melting point apparatus, UK and were uncorrected.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity was tested using normal embryonic lung cells (MRC-5). The cells were grown in DMEM medium supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin–streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum. Briefly, cell lines suspended in the culture medium were seeded in a 96-well microtiter plate (3599; Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) at a density of 5×103 to 2×104 cells/well, and incubated at 37°C under a humidified atmosphere (95% air, 5% CO2) for 24 hours. An equal volume of additional medium containing either the serial dilutions of the tested compounds, positive control (doxorubicin), or negative control (DMSO) was added to the desired final concentrations. The plates were further incubated for an additional 48 hours. Cell viability was determined by staining with MTT assay.63–65 The MTT solution (10 μL/100 μL medium) was added to all wells of an assay and plates were incubated as described above for 2–4 hours. Subsequently, DMSO was added to dissolve the resulting formazan by sonication. The plates were read on a microplate reader (Molecular Devices LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) using a test wavelength of 550 nm and a reference wavelength of 650 nm. IC50 value is defined as the drug or the compound concentration that inhibits cell growth by 50% (relative to negative control).

Aromatase inhibition assay

Aromatase inhibitory effect of metal complexes (4–9) and free ligands (1–3) was performed using the method reported by Stresser et al,66 with minor modifications. This method was carried out according to the Gentest kit using CYP19 enzyme and DBF as a fluorometric substrate. DBF was dealkylated by aromatase and then hydrolyzed, providing the fluorescein product.

For the aromatase inhibition assay, 100 μL of cofactor, containing 78.4 μL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4); 20 μL of 20× nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-generating system (26 mM NADP+, 66 mM glucose-6-phosphate, and 66 mM MgCl2); and 1.6 μL of 100 U/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, were pipetted into a 96-well black plate and preincubated in a water bath (37°C) for 10 minutes. The reaction was initiated by addition of 100 μL of enzyme/substrate (E/S) mixture containing 77.3 μL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4); 12.5 μL of 16 pmol/mL CYP19; 0.2 μL of 0.2 mM DBF; and 10 μL of 0.25 mM diluted tested sample (or 10% DMSO as a negative control or ketoconazole 52 μM or letrozole 6.6 nM as a positive control). To exclude background fluorescence of the sample, E/S was added after the reaction was terminated. After incubation at 37°C for 30 minutes, the reaction was stopped by addition of 50 μL of 2.2 N NaOH. To develop adequate signal-to-background ratio, the plate (with lid) was then incubated for 2 hours at 37°C in an air incubator. Fluorescence signal was measured using an excitation wavelength of 490 nm and emission wavelength of 530 nm with cutoff 515 nm. Percentage of inhibition (% inhibition) was calculated by Equation 1. Samples with % inhibition greater than 50 were further diluted and assayed in triplicate. Finally, IC50 values were determined by the plot of concentrations versus % inhibitions.

| (1) |

Results

Metal complexes of 8HQ–uracils (4–9) and free ligands (1–3) were investigated for their aromatase inhibitory activity and cytotoxicity toward normal embryonic lung (MRC-5) cells.

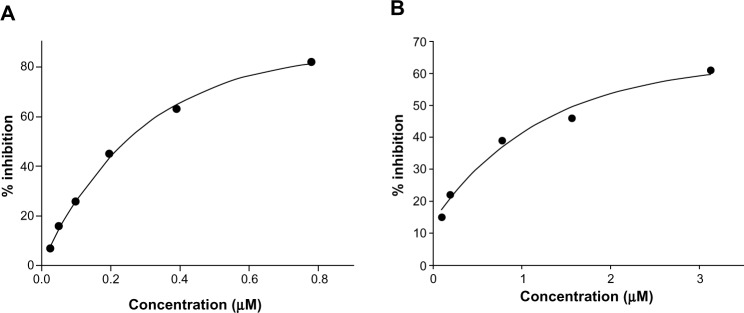

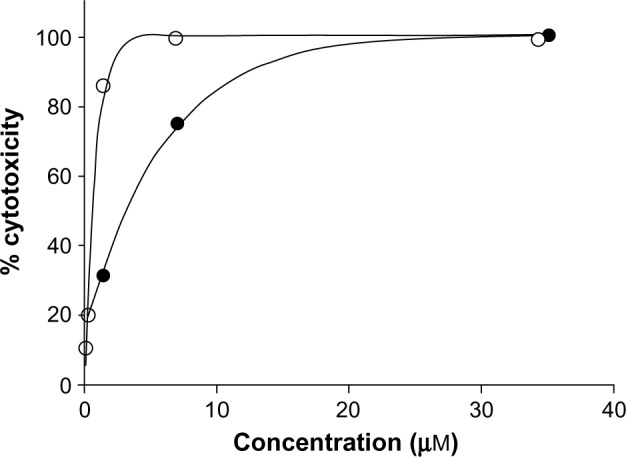

The results (Table 1) revealed that only Cu complexes (6 and 9) exhibited aromatase inhibitory effect in a dose-dependent manner, with IC50 0.30 and 1.70 μM, respectively. Mn complexes (5 and 8), Ni complexes (4 and 7), and all free ligands (1–3) were shown to be inactive. The plots of concentration versus % inhibition of active complexes (6 and 9) are shown in Figure 2. Cytotoxicity test of compounds 1–9 (Table 2) against MRC-5 cells showed that metal complexes (5 and 6) and 8HQ exhibited the activity, with IC50 range 0.74–6.27 μM. The dose–response curves of complexes (5 and 6) are shown in Figure 3.

Table 1.

Aromatase inhibitory (IC50) activity of metal complexes

| Compound | IC50 (μM)a |

|---|---|

| 8HQ (1) | Inactiveb |

| 5Nu (2) | Inactiveb |

| 5Iu (3) | Inactiveb |

| 8HQ–Ni–5Nu (4) | Inactiveb |

| 8HQ–Mn–5Nu (5) | Inactiveb |

| 8HQ–Cu–5Nu (6) | 0.30±0.04 |

| 8HQ–Ni–5Iu (7) | Inactiveb |

| 8HQ–Mn–5Iu (8) | Inactiveb |

| 8HQ–Cu–5Iu (9) | 1.70±0.50 |

| Letrozolec | 0.33±0.40d |

| Ketoconazolec | 2.60±0.70 |

Notes:

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, n=3

inactive denotes compound with inhibition ≤50% at 12.5 μM

letrozole and ketoconazole were used as reference drugs.

IC50 is shown as nM.

Abbreviations: 5Iu, 5-iodouracil; 5Nu, 5-nitrouracil; 8HQ, 8-hydroxyquinoline.

Figure 2.

Aromatase inhibitory activity of metal complexes 6 (A) and 9 (B).

Table 2.

Cytotoxicity (IC50) of metal complexes against MRC-5 cell line

| Compound | IC50 (μM)a |

|---|---|

| 8HQ (1) | 6.27±0.58 |

| 5Nu (2) | Noncytotoxicb |

| 5Iu (3) | Noncytotoxicb |

| 8HQ–Ni–5Nu (4) | NTc |

| 8HQ–Mn–5Nu (5) | 5.19±1.26 |

| 8HQ–Cu–5Nu (6) | 0.74±0.04 |

| 8HQ–Ni–5Iu (7) | NTc |

| 8HQ–Mn–5Iu (8) | NTc |

| 8HQ–Cu–5Iu (9) | NTc |

| Doxorubicin | Noncytotoxicb |

Notes:

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, n=3

noncytotoxic denotes compounds with IC50 >50 μg/mL

insoluble in testing medium.

Abbreviations: 5Iu, 5-iodouracil; 5Nu, 5-nitrouracil; 8HQ, 8-hydroxyquinoline; NT, not tested.

Figure 3.

Cytotoxicity of metal complexes (5 and 6) against MRC-5 cell line.

Note: Solid circles represent 5 and empty circles represent 6.

Discussion

One of the most commonly occurring types of cancer in women is breast cancer, which is also one of the leading causes of death in women worldwide.67 Estrogens have been found to be one of the leading factors associated with the pathogenesis and progression of estrogen-dependent diseases such as breast cancer1 and endometriosis.8,68 Aromatase is the key enzyme in the rate-limiting step of estrogen production,8 and its inhibition by aromatase inhibitors is one of the approaches to treating and improving prognosis of breast cancer69–71 and estrogen-related diseases.72–74 Recently, aromatase inhibitors have become the drug of choice for estrogen-dependent cancers70,71 and estrogen-related diseases.8,72,73

In this study, a series of 8HQ–uracils metal (Ni, Mn, and Cu) complexes (4–9) were synthesized and investigated for their aromatase inhibitory activity. The results showed that, among all of the tested metal complexes and free ligands, only Cu complexes (6 and 9) were found to be active. Particularly, both Cu complexes were shown to afford more potent aromatase inhibitory activity compared to the positive control, ketoconazole. This can be deduced from the IC50 values of 8HQ–Cu–5Nu (6) and 8HQ–Cu–5Iu (9), which were 8.67- and 1.5-fold less than the ketoconazole, respectively. However, such Cu complexes (6 and 9) displayed weaker aromatase inhibitory activity than letrozole, which is the inhibitor currently used against breast cancer in postmenopausal women. This suggests that Cu ion plays crucial roles in aromatase inhibition. At this point in time, the aromatase inhibition by 8HQ–Cu–uracil (5Nu and 5Iu) complexes has not been previously reported.

It is well recognized that Cu ions are considered one of the risk factors predisposing to the development of cancers facilitated by tumor angiogenesis, growth, and metastasis.75–77 Elevated levels of Cu ions are found in tissues and serum of patients with cancers such as breast, prostate, colon, brain, and lung cancer.78–81 These observations suggest that Cu could serve as one of the selective targets for the treatment of cancers.82

The mechanism of action of non-steroidal aromatase inhibitors can be attributed to their lone-pair electrons as carried by heteroatoms of azole rings that interact with the Fe atom of the porphyrin ring inside the binding site of aromatase, thereby leading to the inactivation of the enzyme.23 Complexation or coordination of metal ions and ligands occurs in a dynamic fashion, as the complexation or coordination of metal ions and ligands can bind in a reversible manner. The dynamic and reversible fashion of binding between metal ions and ligands can be used to explain the experimental results of metal complexes. In this study, metal complexes (4–9) were formed by metal center atoms binding with two different ligands. The possible release mechanism of metal complexes is dependent on electronegativity and metal binding affinity of ligands, as well as pKa at the site of action. Owing to the inherent nature of positively charged metal ions, they mostly occur in the bound state with negatively charged or electron donor molecules.83 Thus, the metal complex may possibly dissociate into one free ligand and one positively charged metal-bound ligand.39,84 Moreover, different sites of metal complex dissociation give rise to different products. The site of metal complex breakage is dependent on the binding affinity between metal ions and each ligand as well as the electronegativity of the ligands.

8HQ is the investigated ligand with a potent metal chelating ability.33,85–87 It contains lone-pair electron donors as carried by the ring’s nitrogen (N) as well as oxygen (O) atom of the OH group, which can be donated upon metal complexation. Therefore, the metal ion may possibly retain its binding with 8HQ. On the other hand, the high electronegativity property of uracil ligands (5Iu or 5Nu) can result in the release of 8HQ–metal charged complex and free uracil ligand.39,61 Our results suggest that Cu is required for aromatase inhibition. A plausible explanation may be attributed to the redox-reactive nature of Cu ion that gives rise to its high affinity to bind electrons and organic molecules.83 Therefore, Cu ions in the released complexes (possibly 8HQ–Cu) could bind to organic compartments of aromatase enzyme, which may consequently cause conformational change of the enzyme leading to perturbation of the catalytic activity. Alternatively, the released 8HQ–Cu charged complex could interact with the target site and subsequently release 8HQ free ligand, which is a potent Fe chelator.84,88 Consequently, 8HQ could possibly chelate Fe contained within the aromatase enzyme, thereby leading to the inactivation of the aromatase enzyme. However, our results indicate that the free ligand 8HQ was an inactive aromatase inhibitor with 18% inhibitory effect at 12.5 μM. It is therefore reasonable to consider that the inhibitory activity requires the compound to have high absorption to the target site of action. This is clearly observed for highly lipophilic 8HQ–Cu–5Nu (5Iu) complexes (6 and 9) as compared to the free ligand 8HQ. A closer look at the structure of 8HQ–metal–uracil complexes revealed that the electronegativity of coordinating atoms of uracil ligands influenced the dissociation of the complexes. Particularly, two O atoms were used in 5Nu complexation, while two carbon (C) atoms with double bond were used in the case of 5Iu. The electronegativity of the O atom is much higher than that of the C atom. Therefore, the electron withdrawing effect of 5Nu is much stronger than that of 5Iu, leading to a higher ability of 5Nu to dissociate from the molecule of metal complex. This phenomenon could be used in explaining why the 8HQ–Cu–5Nu complex (6) exhibited more potent aromatase inhibitory effect than that of the 8HQ–Cu–5Iu complex (9). The Cu complex 6 displayed a higher IC50 value (0.74 μM) in cytotoxicity, compared to its aromatase inhibition with IC50 of 0.30 μM. Other metal (Ni and Mn) complexes (4, 5, 7 and 8), as inactive aromatase inhibitors, exerted their weak inhibitory effects at 12.5 μM in the percentage of 8%, 33%, 13%, and 27%, respectively. This may be due to the property of metal-centered atoms affecting the compounds’ interactions with the target site of action.

Selectivity is another important issue to consider in the development of anticancer drugs.54 It was found that drugs with poor selectivity can cause undesirable toxicities.89 Since, cancers require Cu ions for their growth and metastasis.75–77 For medicinal use, Cu ion could be a selective target in cancer therapy.82 In addition, 8HQ90 and uracil derivatives45 are anticancer agents.88,91 Particularly, 8HQ has been shown to provide substantial cytotoxic activity against the human breast cancer MCF-7 cell line.35

Conclusion

Aromatase inhibitors represent one of the most promising types of agent for the treatment of estrogen-dependent cancers and diseases. A series of mixed-ligand 8HQ–uracil derivative metal complexes were synthesized and investigated for their aromatase inhibitory and cytotoxic activities. Notably, among all of the tested metal complexes, Cu complexes (6 and 9) were found to act as a novel class of aromatase inhibitor, with higher activity than the reference drug (ketoconazole) but less than the letrozole. Our findings suggest that these 8HQ–Cu–uracil complexes are promising agents that could be potentially developed as a selective anticancer agent for breast cancer and other estrogen-related diseases.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the research grant of Srinakharinwirot University (BE 2555) and by the Office of the Higher Education Commission, Mahidol University under the National Research Universities Initiative. We gratefully acknowledge the Chulabhorn Research Institute for performing aromatase inhibition and cytotoxic assays.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Brueggemeier RW, Hackett JC, Diaz-Cruz ES. Aromatase inhibitors in the treatment of breast cancer. Endocr Rev. 2005;26(3):331–345. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martín-Millán M, Castañeda S. Estrogens, osteoarthritis and inflammation. Joint Bone Spine. 2013;80(4):368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Straub RH. The complex role of estrogens in inflammation. Endocr Rev. 2007;28(5):521–574. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutolo M, Wilder RL. Different roles for androgens and estrogens in the susceptibility to autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2000;26(4):825–839. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pettersson K, Gustafsson JA. Role of estrogen receptor beta in estrogen action. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63(1):165–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Michet CJ, Jr, McKenna CH, Elveback LR, Kaslow RA, Kurland LT. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus and other connective tissue diseases in Rochester, Minnesota, 1950 through 1979. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60(2):105–113. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60294-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Couse JF, Korach KS. Estrogen receptor null mice: what have we learned and where will they lead us? Endocr Rev. 1999;20(3):358–417. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attar E, Bulun SE. Aromatase and other steroidogenic genes in endometriosis: translational aspects. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12(1):49–56. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmi034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Recanatini M, Cavalli A, Valenti P. Nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitors: recent advances. Med Res Rev. 2002;22(3):282–304. doi: 10.1002/med.10010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simpson ER, Mahendroo MS, Means GD, et al. Aromatase cytochrome P450, the enzyme responsible for estrogen biosynthesis. Endocr Rev. 1994;15(3):342–355. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-3-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schweikert HU, Milewich L, Wilson JD. Aromatization of androstenedione by cultured human fibroblasts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1976;43(4):785–795. doi: 10.1210/jcem-43-4-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perel E, Wilkins D, Killinger DW. The conversion of androstenedione to estrone, estradiol, and testosterone in breast tissue. J Steroid Biochem. 1980;13(1):89–94. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(80)90117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller WR, Hawkins RA, Forrest AP. Significance of aromatase activity in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1982;42(Suppl 8):3365s–3368s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richelson LS, Wahner HW, Melton LJ, Riggs BL. Relative contributions of aging and estrogen deficiency to postmenopausal bone loss. N Engl J Med. 1984;311(20):1273–1275. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198411153112002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osborne CK. Steroid hormone receptors in breast cancer management. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;51(3):227–238. doi: 10.1023/a:1006132427948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson E, Rubin G, Clyne C, et al. The role of local estrogen biosynthesis in males and females. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11(5):184–188. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang S, Fang Z, Suzuki T, et al. Regulation of aromatase P450 expression in endometriotic and endometrial stromal cells by CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins (C/EBPs): decreased C/EBPbeta in endometriosis is associated with overexpression of aromatase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(5):2336–2345. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.5.8486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaki J, Yamamoto T, Okada H. Aromatization of androstenedione by normal and neoplastic endometrium of the uterus. J Steroid Biochem. 1985;22(1):63–66. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(85)90142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe K, Sasano H, Harada N, et al. Aromatase in human endometrial carcinoma and hyperplasia. Immunohistochemical, in situ hybridization, and biochemical studies. Am J Pathol. 1995;146(2):491–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Löfgren L, Wallberg B, Wilking N, et al. Tamoxifen and megestrol acetate for postmenopausal breast cancer: diverging effects on liver proteins, androgens, and glucocorticoids. Med Oncol. 2004;21(4):309–318. doi: 10.1385/MO:21:4:309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sainsbury R. The development of endocrine therapy for women with breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2013;39(5):507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brueggemeier RW, Li PK, Chen HH, Moh PP, Katlic NE. Biochemical and pharmacological development of steroidal inhibitors of aromatase. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;37(3):379–385. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(90)90488-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graves PE, Salhanick HA. Stereoselective inhibition of aromatase by enantiomers of aminoglutethimide. Endocrinology. 1979;105(1):52–57. doi: 10.1210/endo-105-1-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanden Bossche H, Willemsens G, Roels I, et al. R 76713 and enantiomers: selective, nonsteroidal inhibitors of the cytochrome P450-dependent oestrogen synthesis. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;40(8):1707–1718. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90346-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mason JI, Murry BA, Olcott M, Sheets JJ. Imidazole antimycotics: inhibitors of steroid aromatase. Biochem Pharmacol. 1985;34(7):1087–1092. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(85)90613-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steele RE, Mellor LB, Sawyer WK, Wasvary JM, Browne LJ. In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrating potent and selective estrogen inhibition with the nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor CGS 16949A. Steroids. 1987;50(1–3):147–161. doi: 10.1016/0039-128x(83)90068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhatnagar AS, Häusler A, Schieweck K, Lang M, Bowman R. Highly selective inhibition of estrogen biosynthesis by CGS 20267, a new non-steroidal aromatase inhibitor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1990;37(6):1021–1027. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(90)90460-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Albrecht M, Fiege M, Osetska O. 8-Hydroxyquinolines in metallosupramolecular chemistry. Coord Chem Rev. 2008;252(8–9):812–824. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lescoat G, Léonce S, Pierré A, Gouffier L, Gaboriau F. Antiproliferative and iron chelating efficiency of the new bis-8-hydroxyquinoline benzylamine chelator S1 in hepatocyte cultures. Chem Biol Interact. 2012;195(2):165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prachayasittikul S, Worachartcheewan A, Pingaew R, et al. Metal complexes of uracil derivatives with cytotoxicity and superoxide scavenging activity. Lett Drug Des Discov. 2012;9(3):282–287. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding WQ, Lind SE. Metal ionophores – an emerging class of anticancer drugs. IUBMB Life. 2009;61(11):1013–1018. doi: 10.1002/iub.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daniel KG, Chen D, Orlu S, Cui QC, Miller FR, Dou QP. Clioquinol and pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate complex with copper to form proteasome inhibitors and apoptosis inducers in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(6):R897–R908. doi: 10.1186/bcr1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prachayasittikul V, Prachayasittikul S, Ruchirawat S, Prachayasittikul V. 8-Hydroxyquinolines: a review of their metal chelating properties and medicinal applications. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7:1157–1178. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S49763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zheng H, Gal S, Weiner LM, et al. Novel multifunctional neuroprotective iron chelator-monoamine oxidase inhibitor drugs for neurodegenerative diseases: in vitro studies on antioxidant activity, prevention of lipid peroxide formation and monoamine oxidase inhibition. J Neurochem. 2005;95(1):68–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng H, Weiner LM, Bar-Am O, et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of novel bifunctional iron-chelators as potential agents for neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and other neurodegenerative diseases. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13(3):773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pavlov A, Takuchev N, Georgieva N. Drug design by regression analyses of newly synthesized derivatives of 8-quinolinol. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment. 2012;26(1):164–169. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeon JH, Lee CH, Lee HS. Antimicrobial activities of 2-methyl-8-hydroxyquinoline and its derivatives against human intestinal bacteria. Journal of the Korean Society for Applied Biological Chemistry. 2009;52(2):202–205. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmed SM, Ismail DA. Synthesis and biological activity of 8-hydroxyquinoline and 2-hydroxypyridine quaternary ammonium salts. J Surfactants Deterg. 2008;11(3):231–235. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srisung S, Suksrichavalit T, Prachayasittikul S, Ruchirawat S, Prachayasittikul V. Antimicrobial activity of 8-hydroxyquinoline and transition metal complexes. International Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;9(2):170–175. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strobl JS, Seibert CW, Li Y, et al. Inhibition of Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium falciparum infections in vitro by NSC3852, a redox active antiproliferative and tumor cell differentiation agent. J Parasitol. 2009;95(1):215–223. doi: 10.1645/GE-1608.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scheibel LW, Adler A. Antimalarial activity of selected aromatic chelators. III. 8-Hydroxyquinolines (oxines) substituted in positions 5 and 7, and oxines annelated in position 5,6 by an aromatic ring. Mol Pharmacol. 1982;22(1):140–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madrid PB, Sherrill J, Liou AP, Weisman JL, Derisi JL, Guy RK. Synthesis of ring-substituted 4-aminoquinolines and evaluation of their antimalarial activities. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15(4):1015–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim YH, Woo KJ, Lim JH, et al. 8-Hydroxyquinoline inhibits iNOS expression and nitric oxide production by down-regulating LPS-induced activity of NF-kappaB and C/EBPbeta in Raw 264.7 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;329(2):591–597. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.01.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamato M, Hashigaki K, Yasumoto Y, et al. Synthesis and antitumor activity of tropolone derivatives. 6. Structure-activity relationships of antitumor-active tropolone and 8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives. J Med Chem. 1987;30(10):1897–1900. doi: 10.1021/jm00393a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Álvarez P, Marchal JA, Boulaiz H, et al. 5-Fluorouracil derivatives: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2012;22(2):107–123. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2012.661413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marchal JA, Boulaiz H, Rodríguez-Serrano F, et al. 5-fluorouracil derivatives induce differentiation mediated by tubulin and HLA class I modulation. Med Chem. 2007;3(3):233–239. doi: 10.2174/157340607780620671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adelstein DJ, Li Y, Adams GL, et al. An intergroup phase III comparison of standard radiation therapy and two schedules of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with unresectable squamous cell head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(1):92–98. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adelstein DJ, Saxton JP, Lavertu P, et al. Maximizing local control and organ preservation in stage IV squamous cell head and neck cancer with hyperfractionated radiation and concurrent chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(5):1405–1410. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moertel CG, Childs DS, Jr, Reitemeier RJ, Colby MY, Jr, Holbrook MA. Combined 5-fluorouracil and supervoltage radiation therapy of locally unresectable gastrointestinal cancer. Lancet. 1969;294(7626):865–867. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(69)92326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seitz JF, Milan C, Giovannini M, et al. Fondation Française de Cancérologie Digestive. Groupe Digestif de la Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer Concurrent concentrated radio-chemotherapy of epidermoid cancer of the esophagus. Long-term results of a phase II national multicenter trial in 122 non-operable patients (FFCD 8803) Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2000;24(2):201–210. French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saniger E, Campos JM, Entrena A, et al. Medium benzene-fused oxacycles with the 5-fluorouracil moiety: synthesis, antiproliferative activities and apoptosis induction in breast cancer cells. Tetrahedron. 2003;59(29):5457–5467. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Espinosa A, Marchal JA, Aránega A, Gallo MA, Aiello S, Campos J. Antitumoural properties of benzannelated seven-membered 5-fluorouracil derivatives and related open analogues. Molecular markers for apoptosis and cell cycle dysregulation. Farmaco. 2005;60(2):91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.farmac.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saniger E, Campos JM, Entrena A, et al. Neighbouring-group participation as the key step in the reactivity of acyclic and cyclic salicyl-derived O,O-acetals with 5-fluorouracil. Antiproliferative activity, cell cycle dysregulation and apoptotic induction of new O,N-acetals against breast cancer cells. Tetrahedron. 2003;59(40):8017–8026. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mazzaferro S, Bouchemal K, Ponchel G. Oral delivery of anticancer drugs II: the prodrug strategy. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18(1–2):93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rafique S, Idrees M, Nasim A, Akbar H, Athar A. Transition metal complexes as potential therapeutic agents. Biotechnology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2010;5(2):38–45. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jackson A, Davis J, Pither RJ, Rodger A, Hannon MJ. Estrogen-derived steroidal metal complexes: agents for cellular delivery of metal centers to estrogen receptor-positive cells. Inorg Chem. 2001;40(16):3964–3973. doi: 10.1021/ic010152a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brow JM, Pleatman CR, Bierbach U. Cytotoxic acridinylthiourea and its platinum conjugate produce enzyme-mediated DNA strand breaks. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12(20):2953–2955. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hambley TW. Developing new metal-based therapeutics: challenges and opportunities. Dalton Trans. 2007;(43):4929–4937. doi: 10.1039/b706075k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suksrichavalit T, Prachayasittikul S, Nantasenamat C, Isarankura-Na-Ayudhya C, Prachayasittikul V. Copper complexes of pyridine derivatives with superoxide scavenging and antimicrobial activities. Eur J Med Chem. 2009;44(8):3259–3265. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suksrichavalit T, Prachayasittikul S, Piacham T, Isarankura-Na-Ayudhya C, Nantasenamat C, Prachayasittikul V. Copper complexes of nicotinic-aromatic carboxylic acids as superoxide dismutase mimetics. Molecules. 2008;13(12):3040–3056. doi: 10.3390/molecules13123040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pingaew R, Worachartcheewan A, Prachayasittikul V, Prachayasittikul S, Ruchirawat S, Prachayasittikul V. Transition metal complexes of 8 aminoquinoline-5-substituted uracils with antioxidative and cytotoxic a ctivities. Lett Drug Des Discov. 2013;10(9):859–864. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Castonguay A, Doucet C, Juhas M, Maysinger D. New ruthenium(II)-letrozole complexes as anticancer therapeutics. J Med Chem. 2012;55(20):8799–8806. doi: 10.1021/jm301103y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1–2):55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carmichael J, DeGraff WG, Gazdar AF, Minna JD, Mitchell JB. Evaluation of a tetrazolium-based semiautomated colorimetric assay: assessment of chemosensitivity testing. Cancer Res. 1987;47(4):936–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tominaga H, Ishiyama M, Ohseto F, et al. A water-soluble tetrazolium salt useful for colorimetric cell viability assay. Analytical Communications. 1999;36(2):47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stresser DM, Turner SD, McNamara J, et al. A High-throughput screen to identify inhibitors of aromatase (CYP19) Anal Biochem. 2000;284(2):427–430. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(2):71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bulun SE, Noble LS, Takayama K, et al. Endocrine disorders associated with inappropriately high aromatase expression. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;61(3–6):133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dowsett M, Cuzick J, Ingle J, et al. Meta-analysis of breast cancer outcomes in adjuvant trials of aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):509–518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mouridsen H, Gershanovich M, Sun Y, et al. Superior efficacy of letrozole versus tamoxifen as first-line therapy for postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer: results of a phase III study of the international letrozole breast cancer group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(10):2596–2606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.10.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Paridaens RJ, Dirix LY, Beex LV, et al. Phase III study comparing exemestane with tamoxifen as first-line hormonal treatment of metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women: the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Breast Cancer Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(30):4883–4890. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shippen ER, West WJ., Jr Successful treatment of severe endometriosis in two premenopausal women with an aromatase inhibitor. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(5):1395–1398. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Takayama K, Zeitoun K, Gunby RT, Sasano H, Carr BR, Bulun SE. Treatment of severe postmenopausal endometriosis with an aromatase inhibitor. Fertil Steril. 1998;69(4):709–713. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(98)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amsterdam LL, Gentry W, Jobanputra S, Wolf M, Rubin SD, Bulun SE. Anastrazole and oral contraceptives: a novel treatment for endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(2):300–304. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brewer GJ. Copper control as an antiangiogenic anticancer therapy: lessons from treating Wilson’s disease. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2001;226(7):665–673. doi: 10.1177/153537020222600712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Theophanides T, Anastassopoulou J. Copper and carcinogenesis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;42(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(02)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Daniel KG, Harbach RH, Guida WC, Dou QP. Copper storage diseases: Menkes, Wilsons, and cancer. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2652–2662. doi: 10.2741/1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nayak SB, Bhat VR, Upadhyay D, Udupa SL. Copper and ceruloplasmin status in serum of prostate and colon cancer patients. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;47(1):108–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang YL, Sheu JY, Lin TH. Association between oxidative stress and changes of trace elements in patients with breast cancer. Clin Biochem. 1999;32(2):131–136. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9120(98)00096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rizk SL, Sky-Peck HH. Comparison between concentrations of trace elements in normal and neoplastic human breast tissue. Cancer Res. 1984;44(11):5390–5394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Turecký L, Kalina P, Uhlíková E, Námerová S, Križko J. Serum ceruloplasmin and copper levels in patients with primary brain tumors. Klin Wochenschr. 1984;62(4):187–189. doi: 10.1007/BF01731643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chen D, Cui QC, Yang H, et al. Clioquinol, a therapeutic agent for Alzheimer’s disease, has proteasome-inhibitory, androgen receptor-suppressing, apoptosis-inducing, and antitumor activities in human prostate cancer cells and xenografts. Cancer Res. 2007;67(4):1636–1644. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bleackley MR, Macgillivray RTA. Transition metal homeostasis: from yeast to human disease. Biometals. 2011;24(5):785–809. doi: 10.1007/s10534-011-9451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Anjaneyulu Y, Rao RP, Swamy RY, Eknath A, Rao KN. In vitro antimicrobial-activity studies on the mixed ligand complexes of Hg(II) with 8-hydroxyquinoline and salicylic acids. Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences – Chemical Sciences. 1982;91(2):157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pollak Y, Mechlovich D, Amit T, et al. Effects of novel neuroprotective and neurorestorative multifunctional drugs on iron chelation and glucose metabolism. J Neural Transm. 2013;120(1):37–48. doi: 10.1007/s00702-012-0795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Crouch PJ, Barnham KJ. Therapeutic redistribution of metal ions to treat Alzheimer’s disease. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45(9):1604–1611. doi: 10.1021/ar300074t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cherny RA, Atwood CS, Xilinas ME, et al. Treatment with a copper-zinc chelator markedly and rapidly inhibits beta-amyloid accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. Neuron. 2001;30(3):665–676. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00317-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bush AI, Tanzi RE. Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease based on the metal hypothesis. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5(3):421–432. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Malet-Martino M, Martino R. Clinical studies of three oral prodrugs of 5-fluorouracil (Capecitabine, UFT, S-1): a review. Oncologist. 2002;7(4):288–323. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-4-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ding WQ, Liu B, Vaught JL, Yamauchi H, Lind SE. Anticancer activity of the antibiotic clioquinol. Cancer Res. 2005;65(8):3389–3395. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shaw AY, Chang CY, Hsu MY, et al. Synthesis and structure-activity relationship study of 8-hydroxyquinoline-derived Mannich bases as anticancer agents. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45(7):2860–2867. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]