Abstract

Coating surfaces with thin or thick films of zwitterionic material is an effective way to reduce or eliminate nonspecific adsorption to the solid/liquid interface. This review tracks the various approaches to zwitteration, such as monolayer assemblies and polymeric brush coatings, on micro- to macroscopic surfaces. A critical summary of the mechanisms responsible for antifouling shows how zwitterions are ideally suited to this task.

Introduction

Reducing the adhesion of environmental molecules and systems to surfaces has long been a goal of applied surface science. The most active areas of current research are at the biological interface: preventing the in vivo and in vitro adhesion of biomolecules, cells, and bacteria to objects and the fouling of surfaces by marine organisms.1,2 Materials for nonfouling coatings have many properties in common. They are usually neutral or weakly negative and well hydrated. Numerous hydrophilic, net-neutral monomers and polymers have been pressed into service,3 including acrylamides, polysaccharides (e.g., mannitol4), and, most commonly, polymers or oligomers based on the ethylene glycol, EG, (−CH2–CH2–O−) repeat unit, termed PEGs. PEGylation refers, in addition to general nonfouling applications, to the modification of a molecule or surface with EG repeat units to decrease interactions in a biological environment5 and therefore enhance the circulation (of molecules and nanoparticles) or residence time (of implants).

The use of zwitterions against fouling was inspired by the external surface of the mammalian cell membrane, rich in phospholipids bearing zwitterion headgroups, notably phosphatidylcholine.6 The balance of this surface is made up with neutral or anionic phospholipids. These zwitterions are presented mainly at the extracellular side of the lipid double layer, the cytoplasmic side of the cell membrane having far fewer zwitterions.6 The antifouling properties of a single monolayer of a lipid zwitterion are all the more remarkable considering it rests on an extremely hydrophobic blanket of hydrocarbon chains.

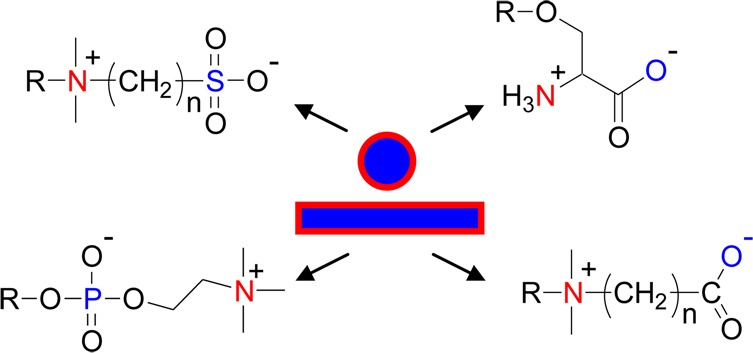

Some of the more common zwitterion functional groups are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Zwitterionic functional groups and one zwitterated siloxane.

Around 1980, after the PC headgroup was shown to be nonthromobogenic,7 several groups polymerized zwitterionic phosphatidylcholine analogues to create stabilized membranes.8−13 Diacetylenes in lipid tails were used in these early works to photopolymerize vesicles or membranes. Synthetic polymer zwitterions were introduced by Ladenheim and Morawetz14 and Hart and Timmerman.15

As summarized later, some of the high-performance materials that have met the nonfouling challenge exceptionally well rely on a synergistic combination of surface and polymer science.

Historically (dating back to the late 1970s), research into zwitterion coatings has followed two trajectories: one focused on biocompatible materials and the other on more general nonfouling at interfaces.

While the concept of biocompatibility is often linked to nonbiofouling, the two are not synonymous, even though there is strong overlap in the technology used to implement them.16 Biocompatibility, implying in vivo applications, has more stringent requirements than simple nonadhesion.17 Ideally, platelets must not be activated.18 In vivo surfaces must not initiate the foreign body recognition system, for example, the tagging of particles by opsonins to be cleared by phagocytes.19 Of course, a completely nonfouling surface might achieve this, but the point is that proving biocompatibility requires more than proving nonfouling properties.

Conversely, biocompatibility does not necessarily mean or require nonfouling. Many materials, such as polyurethane, polyethylene, siloxane polymers, and titanium, to which proteins rapidly adsorb are classified as biocompatible. In reality, these “medical-grade” materials tolerate fouling for the location and time period for which they are used.

This review begins with a survey of how zwitteration has been implemented at macroscopic or planar surfaces and at the surfaces of nanoparticles. A further breakdown is provided on how zwitterion functional groups have been deployed in two dimensions (monolayers) and three dimensions. After this attempt to link historical threads, a discussion on the poorly appreciated topic of zwitterion interactions is followed by a critical analysis of the mechanisms for nonfouling, with comparison to PEG where appropriate.

Planar Surfaces

Bulk Zwitterion Polymers

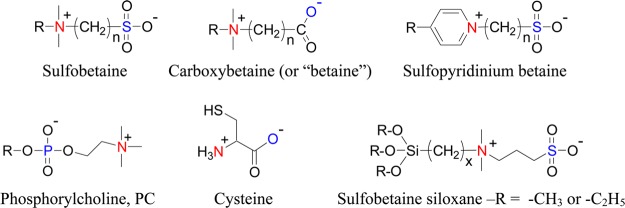

The zwitteration of bulk polymeric materials to render them biocompatible started with the PC functionality. MPC itself (Figure 2) was invented by Nakabayashi’s group in 1977.20 PC polymers have poor structural integrity and so are combined with tougher materials such as segmented polyurethanes.21 Copolymers with PC units were reviewed extensively at the turn of the millenium by Nakaya and Li21 and by Lewis.22 Copolymers of hydroxyethyl methacrylate, HEMA, a common contact lens material, and MPC have been in commercial use for nonfouling extended-wear lenses for some time (as omafilcon A).23

Figure 2.

Three examples of zwitterionic polymers: poly(methacryloyloxylethyl phosphorylcholine), polyMPC; poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate), polySBMA; and poly(sulfobetaineacrylamide), polySBAAm.

For these bulk materials, rather than relying on a multistep process of making the polymer article and then coating it with an adhering layer of MPC, the zwitterion is incorporated as a comonomer. The zwitterionic functionality presumably orients to the surface on contact with water24 in a kind of amorphous self-assembly. Zwitterion comonomers enhance the surface hydrophilicity of dimethylsiloxane polymers,25 as illustrated by a reduced water contact angle.24

Despite the manufacturing convenience of adding a zwitterion comonomer, depositing a nonfouling coating is a more versatile strategy, as this approach preserves the optimized bulk property of the coated material, whether it is a polymer, metal, or ceramic, while rendering it biocompatible.

Monolayer

The properties of liposomes prepared from zwitterion phospholipids, including those made stealthy by PEGylation,26,27 have been reviewed28 and are not discussed here. Surfaces modified with zwitterion surfactants29 are somewhat unstable, requiring a reservoir of dissolved surfactant to keep them in place (dynamic coating30). The early photopolymerized membrane mimics8−13 were more stable but were not employed for practical materials, requiring, for example, assembly and compression at the air/water interface using a Langmuir trough.

Adsorption driven by strong interactions of sulfur with gold was introduced as a new method to organize monolayers at surfaces.31 The Regen group extended their earlier work on photopolymerized PC lipids10 by preparing self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) of a zwitterionic phosphorylcholine thiol on gold.32,33 These studies included dithiols, which should yield more stable monolayers,34 and lipoic acid (disulfide) functionalities, similar to those used recently to make zwitterionic monolayers on gold35 and semiconductor36 nanoparticles. The efficiency of zwitterionic SAMs in preventing protein adsorption was later demonstrated by Tegoulia et al.37 and the groups of Whitesides38 and Jiang.39

Films

Lowe et al. described a statistical copolymer of butyl acrylate (anchoring groups) with sulfobetaines which, when adsorbed to plastic discs, reduced the adhesion of bacteria and fibroblasts.40 Another way of depositing a polymeric film of zwitterions is to incorporate them into a polyelectrolyte multilayer. We layered SBAAm-co-acrylic acid copolymers with polycations to protect surfaces from cell41 and protein adsorption.42 Interestingly, multilayers presenting both oligoethylene glycol and PC in a pendant group were not quite as efficiently nonfouling as the EG oligomer by itself.43

Zwitterionic polymers brushes may be grafted to44 or grafted from45−50 surfaces. Though not designed for antifouling, zwitterion polymers, prepared as monoliths or attached to chromatographic support media, were used by the Irgum group to separate ions and proteins.51−54 In 2002, Jiang and Irgum reported SBMA polymer brushes (which they called tentacles) grafted from silica particles using surface-bound radical initiators.53 Xu et al.55 produced phospholipid analogue brushes at a polypropylene surface by photoinduced graft polymerization of a dimethylamino vinyl monomer followed by the conversion of the grafted polymer to polyzwitterions with oxo-dioxaphospholanes. With sufficient grafting density, these coatings could reduce the adsorption of serum albumin substantially. Exceptionally low friction in solution was observed between surfaces grafted with zwitterionic brushes.56

Because of the increasing number of ATRP (atom-transfer radical polymerization) and other living polymerization tools, grafting—from, which generally yields denser, more volume-excluding brushes, has become popular. Feng et al. grew MPC brushes from silicon wafers using ATRP,57 which was shown to decrease protein and cell adhesion significantly.58,59 Zwitterion brushes grown from surfaces have been extensively reported by Jiang’s group.60−62 These coatings demonstrated particularly effective fouling resistance, even from pure serum.63 Bacterial adhesion was also inhibited.64 Since about 2009 the number of works employing graft polymerization of polyzwitterions from/to surfaces has increased dramatically, as witnessed by grafting from silicon nitride,49,65 polypropylene membranes,66 various surfaces using a bioinspired peptide initiator,67 indium tin oxide conducting glass,48 gold,68 hydrogels,69 filtration membranes,70 conducting polymers,71 cellulose membranes,72 and polysulfone membranes.73

Nanoparticles (NPs)

Nonfouling coatings confer both nonadhesive properties and colloidal stability to nanoparticles. Both are essential to the use of NPs in nanomedicine for diagnostics and/or therapy.74 Coatings which prevent aggregation, precipitation, or clearance of NPs allow them to circulate in vivo and accumulate at a specific site via passive (such as a leaky vasculature) or active (e.g., using antibodies or aptamers) targeting.75

Monolayers

Cysteine, a zwitterionic amino acid, has been used to decorate nanoparticles such as those made from semiconductors76−78 and gold79 using the chemisorbing properties of the thiol group. Cysteine is not effective at preventing the salt-induced aggregation of Au NPs79 or Ag NPs80 whereas semiconductor nanoparticles81 are stabilized and passivated by a cysteine coating. The difference may be due to a greater stability of the S–semiconductor over the S–Au bond.

The use of synthetic molecules for zwitterionic monolayers on metal NPs followed some time later. Gittins and Caruso82 effected the complete transfer of Au NPs prepared in toluene into an aqueous phase using 4-dimethylaminopyridine as a phase-transfer agent, which has partial zwitterionic character when adsorbed to Au. These NPs, produced at high concentrations, were described as indefinitely stable. Tatumi and Fujihara used an imidazoliumsulfonate-terminated thiol as a capping agent,83 leading to Au nanoparticles that were not soluble in pure water but were soluble and stable in aqueous solutions at high salt concentrations.

We introduced the sulfobetaine motif for stabilizing Au NPs using a disulfide zwitterion.84 The NPs were prepared by simple place exchange of weakly adsorbing citrate ligands with a strongly adsorbing disulfide zwitterion. These zwitterated nanoparticles were very stable, even in aqueous 3 M NaCl. We subsequently extended the sulfobetaine functionality to stabilize silica85,86 and (superparamagnetic) iron oxide nanoparticles,87 employing siloxane condensation chemistry to bind the ligand to the surface.

Thin Films

In some of the earliest work on zwitterated polymer nanoparticles, Yamaguchi et al.88 and Sugiyama and Aoki89 reported the emulsion copolymerization of narrow-size-distribution MPC-containing nanoparticles. The MPC was shown to be localized at the surface, and the nanoparticles decreased, modestly, the amount of serum albumin adsorbed to the surface relative to nonzwitterated NPs. However, aggregation was observed.89 Emulsion-polymerized methacryloyl-l-serine was also observed to reduce protein adsorption on methyl methacrylate nanoparticles.90

Konno et al.91 prepared poly(l-lactic acid) nanoparticles stabilized by a shell of MPC/butyl methacrylate copolymer which yielded low surface zeta potentials and resistance to serum albumin absorption. Uchida et al.92 described the synthesis of styrene nanoparticles with grafted MPC units of about 6000 Da Mn starting with an MPC macromonomer.

In 2003, Chen and Armes reported a versatile method of adsorbing a copolymer with positively charged groups to attach to the surface and R-Br groups from which ATRP could be conducted.45 The resulting polyzwitterion brush on silica nanoparticles is one of the few coatings to demonstrate zeta potentials approaching zero mV over a wide pH range, indicating the efficient masking of all of the charged groups on the silica surface and negligible hydrolysis of the ester functionality. (A monolayer of sulfobetaine siloxane on silica also provides a zero zeta potential.85) The grafting-from methodology is now widely used to produce highly stable zwitterion brushes on silica93 or iron oxide46 NPs.

Interactions

It is sometimes assumed that because zwitterions prevent fouling they do not interact with other species. This is not the case. There is much evidence for interactions with and between zwitterions on surfaces and in solution. In the former case, as with any weak interaction, multiple (polyvalent) associations between macromolecules amplify the effect. The challenge is to engineer zwitterions to minimize interactions with solution species. In the following treatment, it will be assumed that zwitterion functional groups are in their fully ionized state, which for carboxybetaines means that they are above their pKa. Protonated carboxybetaines are not zwitterions. Sulfonate and phosphate groups have sufficiently low pKa to remain fully charged over most working ranges of pH.

Interzwitterion associations depend strongly on the solvent. For example, significant interactions are observed in organic solvents94 and calculated for solvent-free systems.95 Zwitterionic end groups have been used to attach polymer brushes to surfaces in organic solvents.96 Because the nonfouling behavior of zwitterions depends critically on hydration mechanisms, only aqueous solutions will be considered here.

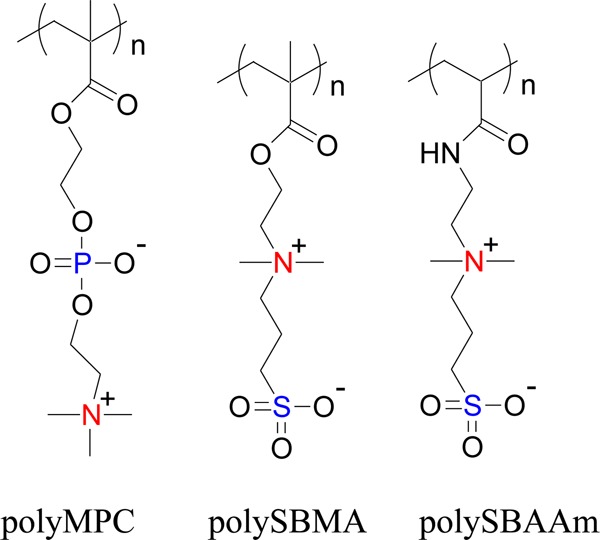

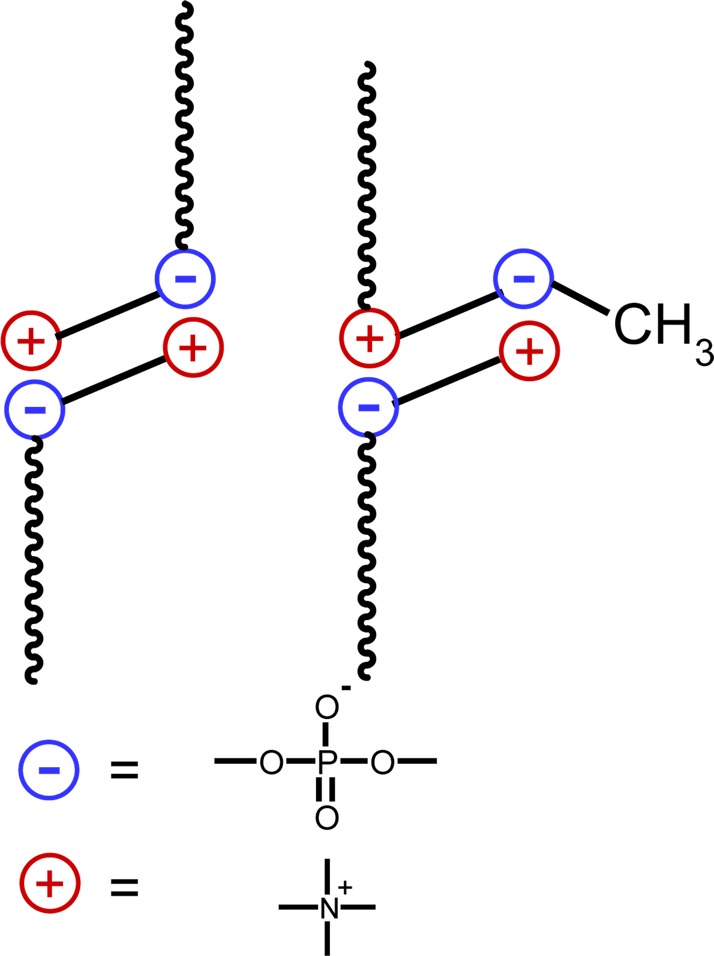

Various inter- and intramolecular ion-pairing scenarios can be proposed (Figure 3) for zwitterions.97,98 For example, interzwitterion pairing requires relatively minor contortions and has been suggested to occur among the dense phospholipid headgroups making up the exterior leaflet of the bilayer cell membrane.99 This type of pairing is supported by neutron diffraction studies100 which show the P–N vector close to parallel to the plane of the bilayer. On the other hand, intramolecular pairing requires the bending around of the headgroup to meet the inner charge or neutralization of the charges through space (i.e., without distortion). Molecular mechanics models show zwitterions to be extended101 with “no evidence of intramolecular ion pairing” (i.e., ring formation) for monomeric zwitterionic surfactants below the critical micelle concentration (CMC).101

Figure 3.

Interaction modes between monomeric and polymeric zwitterions. Added salt breaks interactions.

For carboxybetaines, the strength of ion pairing of zwitterion charges can be probed by titrating the carboxylate group: a decrease in pKa indicates stronger associative interactions (ion pairing) between ammonium and carboxylate (i.e., −COO– becomes harder to protonate). For monomeric carboxybetaines, pKa changes with the distance between zwitterion groups,101,102 which was suggested to be a field effect. In contrast, carboxybetaine repeat units on a polyzwitterion exhibit a constant lowered pKa as a function of intercharge spacing,103 causing the authors to invoke a ring-type interaction.

The contradiction between monomeric and polymeric carboxybetaine pKa behavior may be reconciled by the behavior of zwitterion surfactants such as docosyldimethylammonium hexanoate.102 Below its CMC, the titration curve of this surfactant is described accurately with a single pKa, whereas above the CMC the apparent pKa decreases as the carboxylate is protonated. One interpretation of this phenomenon is that as the ratio of ammonium to carboxylate increases, the carboxylates are more strongly paired with positive charges, making the −COOH a stronger acid (more difficult to protonate). This supports the idea that condensed or neighboring zwitterions interact.

For the purpose of preventing fouling, surface interzwitterion pairing should not be viewed as a problem and may actually enhance antifouling performance; as long as zwitterions are paired with each other they are not interacting with external species.

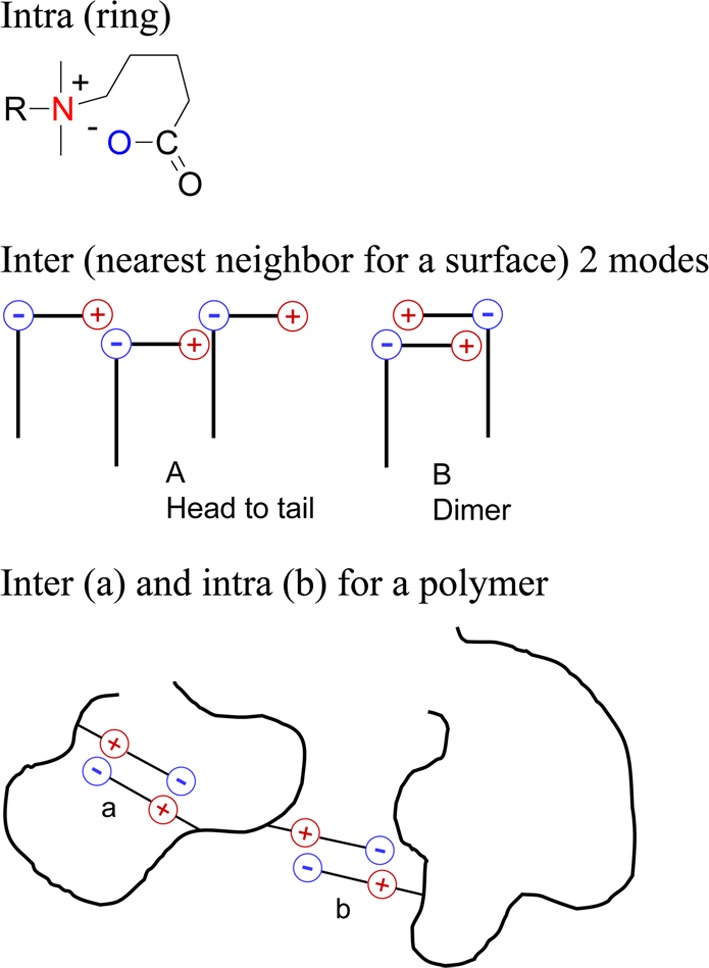

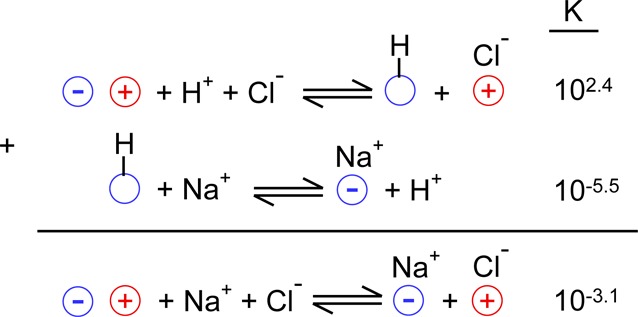

A rough estimate of the strength of ion pairing in zwitterions may be made using the titration data for polycarboxybetaines. According to Izumrudov et al.,103 the pKa for polycarboxybetaines is about 2.4 compared to that of free poly(acrylic acid), which is about 5.5. Scheme 1 uses these two results to estimate the equilibrium constant, 1/K1, for inter/intrazwitterion pairing of carboxylate and pyridinium. Pairing between zwitterions is suggested in a fascinating new class of bioadhesive polymers made with zwitterion pendant groups that have the positions of choline and phosphate (CP) reversed compared to those in PC.104 Adhesion between red blood cells is promoted without rupturing the membranes.105 If intermolecular zwitterion dimerization plays a role, as the authors postulate, then the open question is why is CP/PC binding stronger than PC/PC binding when both zwitterions headgroups are so similar in geometry? The comparison is illustrated in Figure 4.

Scheme 1. Estimate of the Ion Pairing Strength of a Zwitterion.

Ka for polycarboxybetaines is combined with that of the polycarboxylate to arrive at an estimate of the ion pairing strength of a zwitterion, 1/K1 = 103.1, where the zwitterion carboxylate is represented by ⊖ and pyridinium by ⊕.

Figure 4.

Comparison of PC/PC and CP/PC interactions.

It is possible that the one additional methyl group in the CP is enough to induce stronger binding.

Interactions of solution species with zwitterions have been exploited in so-called hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC).54 Chromatographic methods are able to employ weak adsorption because even slight retention leads to resolved separations. Even so, when zwitterated stationary phases106 are used they exhibit such weak interactions with solutes that the mobile phase often requires an organic modifier.54 Zwitterated stationary phases also interact with proteins.52

Ion chromatography reveals the clear retention of both anions and cations on bonded zwitterionic stationary phases in 100% water but only for anions at the less-solvated (chaotropic) end of the Hofmeister series (e.g., perchlorate and thiocyanate salts).51 NaCl showed no retention, indicating minimal interaction,51 a sign of strong intra(inter)zwitterion pairing. Anions and cations work cooperatively; for example, a strongly adsorbed anion, such as perchlorate, enhances the adsorption of a cation. On the other hand, monovalent cations in Cl– are not separated, and only multiply charged cations, such as Zn2+, Ca2+, Ba2+, and Ce3+, are actually retained.51

Solution properties, such as solubility, depend on what groups make up the zwitterions. Polyvinylimidazolium sulfobetaine requires added salt to dissolve,107 as do gold nanoparticles decorated with a thiolated vinylimidazole sulfobetaine.83 PolyMPC dissolves in pure water.108

Interactions between zwitterionic macromolecules are reflected in chain conformations and associations. The “antipolyelectrolyte” effect, expansion of the polymer coil in solution with added salt, is often cited as a property of synthetic polyzwitterions.109 This effect is not consistently observed, with slight expansion seen for some polymer,110,111 or absolutely no change in dimension with added salt.112 PolySBMA expands with added salt only in quite dilute solutions (10–4 to 10–2 M NaCl), perhaps indicating the breaking of intermolecular pairing, but the size remains roughly constant from 10–2 to 1 M.113 In fact, around the conditions relevant for nonfouling applications (0.15 to around 1 M NaCl) little change in size is observed.109

The fact that the antipolyelectrolyte effect in polyzwitterions is mild, if observed at all, is evidence that inter- and intrachain zwitterion pairings are weak. Even 1% intrachain ion pairing should lead to network formation for a polymer of molecular weight >105. For example, Matsuda et al.,112 using static and dynamic light scattering on polyMPC prepared by ATRP, reported no change in the coil hydrodynamic radius, Rh, of 10.5 nm from 0 to 1 M NaCl and no evidence of aggregation for a polymer with Mw = 2 × 105 and Mw/Mn = 1.50.112 PolyMPC with such a molecular weight has a weight-average degree of polymerization, DP, of about 660 repeat units, so the fraction of intermolecular dimers must be less than about 10–3. The polyzwitterion had a much larger coil size (Rg ≈ 16 nm if Rg = 1.5Rh) than the negative polyelectrolyte poly(styrenesulfonate), PSS with a DP of 660 in a θ solvent (4.17 M NaCl at 16.4 °C, Rg = 6.4 nm114) or in 0.5 M NaCl (Rg = 12.2 nm115), or polystyrene, PS, in a θ solvent (Rg = 7.6 nm116), or even a good solvent (Rg ≈ 12 nm117) which does not suggest intersegment attractive forces. The polyMPC Rg is similar to a rather expanded PSS in 0.05 M (16.8 nm).115 These comparisons support the known property that MPC is well hydrated. They are not consistent with intra- or intermolecular interactions. Even nearest-neighbor interactions as in Figure 3 should lead to changes in coil dimension when broken.

Our group found that the interactions between zwitterionic polyelectrolytes and either polyanions or polycations were insufficient for multilayering,41,118 as did Kharlampieva et al.119 It was necessary to copolymerize a charged group, such as acrylate, along with the zwitterion repeat unit41 to provide ion-pairing interactions with a polycation, such as PAH. In contrast, Mary and Bendejacq120 reported the multilayering of a polyzwitterion with a polycation, perhaps because their polyzwitterion was partially hydrolyzed to an acrylate121

Mechanism

To a first approximation, the antifouling mechanism of zwitterion coatings is intuitively straightforward: they are well hydrated with no net charge. On the other hand, if the extensive and conflicting discussion of the nonfouling properties of PEGylated surfaces is extended to zwitterions, then the mechanism becomes less clear. I will attempt to take the path of least contradiction, starting with the relevant mechanisms, followed by their contributions, ending with whether they are important in monolayer (2-D) versus film (3-D) zwitterion coatings. Both dimensionalities rely on minimal interaction with solution species, but the film coating has the added benefit of an excluded volume effect (entropy penalty), which prevents large molecules from approaching the surface

Surface Energy Mechanisms–The Watery Surface

All nonfouling surfaces contain a good deal of water. If the surface contains extensive water in a similar state to bulk water, then no free energy can be gained in replacing a protein/water interface with a protein/surface interface by adsorption.16 In other words, a surface with low interfacial energy with water should discourage adsorption driven by interfacial energy change. Ikada analyzed blood-compatible polymers using this rationale.122 Recent measurements by Kobayashi et al. on surfaces coated with MPC and SBMA brushes showed low water-in-air contact angles and high oil-in-water contact angles, indicating such a low surface free energy.123 PolyMPC performed somewhat better than polySBMA in this respect, where the former showed no dependence on salt concentration, in contrast to the latter.108 Wahlgren and Arnebrant warned against using simple surface free energy arguments, as the components of many surfaces are mobile enough to respond to the liquid in which they are immersed.124 For example, if a surface is transferred from water to an organic solvent then the hydrophobic parts of a molecule or chain may flip out to maximize exposure to the solvent. Polyzwitterions show little surfactant activity113 (i.e., they do not perturb the surface free energy of water), which suggests that this type of molecular rearrangement may not occur for zwitterion-modified surfaces or polymers. The hydrophobic parts of the polymer chain are probably too small to be able to segregate with themselves (hydrophobic association) at the entropy cost (reduced chain conformations and translational entropy) that this association would entail.

Water Structure Argument

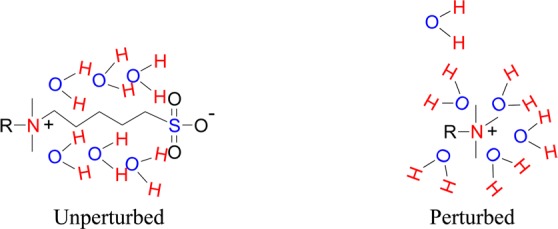

Molecular-level analyses of the nonfouling effectiveness of zwitterions frequently invoke special properties of water, specifically, structural effects on its hydrogen-bonding network.16 Disrupting the hydrogen-bonding network of water comes with a high energy cost as reflected in a large water cohesive energy density.125 At the same time, optimizing the number of hydrogen bonds by the ordering of water leads to a loss of entropy.

Here, the environment for water falls under two broad categories. Associated water hydrates the zwitterion charges directly and is also termed nonfreezing. Unassociated, or bulk, water would be outside the first hydration shell, maintained within the zwitterion layer (whether 2-D or 3-D) by osmotic pressure. Wu et al. estimated that 7 ± 1 water molecules associate specifically with one sulfobetaine zwitterion,126 which is lower than 85% water found by Murphy et al. for an MPC copolymer at the interface127 but about the same as the intrinsic water content in a polyelectrolyte multilayer with quaternary ammonium and sulfonate polyelectrolytes in roughly stoichiometric proportion and with charged groups in similar proximity to each other.128

Molecular dynamics simulations129 show about 7 H2O around a sulfonate group and 19 H2O around the quaternary ammonium in a −N+(CH2)2SO3– sulfobetaine, slightly more than for a similar carboxybetaine. In comparison, thermal analysis of the MPC polymer130 revealed about 58% nonfreezable water, corresponding to about 23 H2O per PC repeat unit.

Is water exceptionally structured by the strong fields around the zwitterion? Zwitterionic stationary phases are ion exchangers only in the presence of hydrophobic (chaotropic or structure-breaking) ions such as perchlorate or thiocyanate.52 Yet the evidence shows that zwitterions do not disrupt the H-bonding structure of water at all. In a highly informative set of experiments using Raman131,132 and FTIR133 spectroscopy, Kitano et al. measured no disruption of the H bonding of water, including associated water, by zwitterionic polyelectrolytes. In contrast, regular polyelectrolytes induced a net loss of hydrogen bonds. Thus, water is not highly structured around zwitterions. More precisely, water appears to be no more or less structured around a zwitterion than in bulk water. The desirability of this property of zwitterions in promoting nonfouling behavior was noted earlier by Laughlin: “The geometry of hydrogen bonding....must resemble that of water molecules within liquid water.”102

Other pieces of evidence point to minimal disruption of the water structure by zwitterions. PolySMBA shows negligible surface activity, indicating that it is perfectly at home in water.113 (There are no sufficiently nonpolar parts that migrate to the surface, and there is no need to banish the molecule to the water/air interface to preserve the H-bonding network.)

That a material can contain about 50 vol % water and still maintain the hydrogen-bonding network of bulk water is remarkable. How might a zwitterion help maintain such a robust network? Figure 5 compares, in cartoon form, water molecules around a zwitterion and a single charge. It is intended to show that the fixed polarity, or proximity, of opposite charges supports the polarity of the water molecules, at least over a correlation length of a few angstroms.

Figure 5.

Representation of differences in water molecule ordering around a zwitterion and a single positive charge. The zwitterion allows the H-bonding structure to remain unperturbed (with reference to bulk water), while the single charge reorients the waters to a more disordered and less H-bonded state.

It should be noted that there is no special reason to have a chemical bond between the zwitterion charges in order to observe the effect in Figure 5. Maintaining one tetraalkylammonium and one sulfonate at a fixed distance should set up the same stabilizing field as in Figure 5. Referring again to our work on polyelectrolyte complexes in the form of multilayered films,128 which contain almost stoichiometric amounts of paired tetraalkylammonium and sulfonate, we could find no difference in the O–H stretching region of water within a polyelectrolyte complex compared to bulk water.128 This nonperturbing charge proximity model would also contribute to the fouling resistance of mixed-charge SAMs38 and amphoteric polymers (which have mixed positive and negative repeat units).

Excluded Volume (Steric) Effects

A neutral, hydrated layer with some thickness, what Ikada122 called a “superhydrophilic diffuse surface”, can be extremely effective at preventing adsorption. Polymer brushes may be well defined, with known height, grafting density, and hydration level. Steric repulsive forces on compressing a brush such as PEG grafted to a surface134,135 contribute to the resistance of a brush or dense surface layer to invasion by particles (colloid stabilization) or macromolecules.

Entropy changes on the brush during protein sorption include the following: (1) osmotic pressure entropic penalties from displaced water; (2) compression or crowding of the polymer chain, reducing its configurational entropy (steric interactions). Enthalpic considerations originate from (1) the dehydration of hydrophilic repeat units and (2) the contact free energy of the polymer with protein. These entropic and some of the enthalpic components work against sorption to hydrophilic net neutral polymer layers from aqueous solution. From the adsorbing protein’s perspective, it loses translational entropy when it adsorbs, experiences a change in contact free energy on going from solvent to the surface, and possibly gains conformational entropy if it denatures136 (but denaturing is not a condition for adsorption). Reducing the mobility of a liquid or mobile surface also carries an entropic cost.

A barrier of water (sometime further described as structured) is often invoked to explain the nonfouling attributes of zwitterions. As mentioned above, there is no unusual structuring of water and water itself does not form a physical barrier. There is an energy barrier, to be sure. Water associated with surface polymers becomes part of the excluded volume portion of the steric mechanism. Water that is not attached is part of the osmotic pressure component of this same mechanism.

Ion-Coupled Driving Forces

Antifouling arguments based only on surface hydrophilicity are quickly derailed. For example, silica is a strongly hydrophilic surface (water contact angle in air of ∼0°), yet silica is a universal adsorber for proteins.137 Thermochemical measurements of serum albumin adsorption to silica reveal an endothermic signature.138 The electrostatic attraction of a positive patch on the protein to the negative surface should be exothermic. Because adsorption is spontaneous, the driving force must include an entropic component that outweighs the positive enthalpic one.

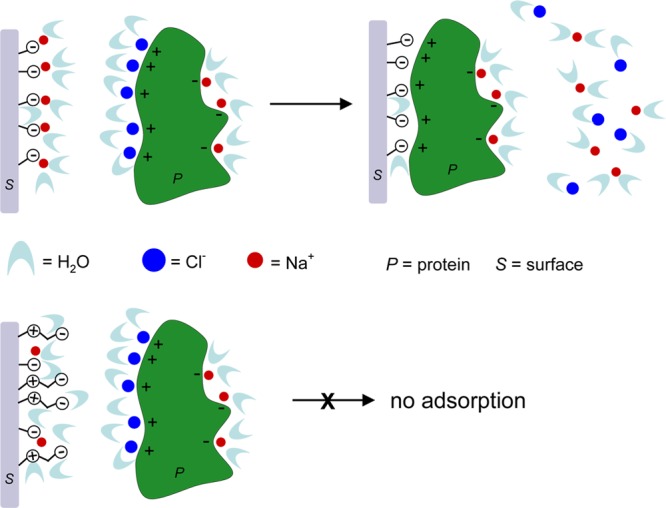

We recently highlighted an ion-exchange mechanism shown in Figure 6 to account for the entropic net driving force for adsorption.86 The adsorption of a positive protein, or positive patch of a net negative protein, results in the formation of ion pairs and the release of counterions. Each ion pair formed releases two counterions.

Figure 6.

Cartoon for the ion-coupled adsorption mechanism of a protein with a positive charge onto a negatively charged hydrophilic substrate, such as a silicon wafer (where the charge comes from ionized silanols). Upper: The adsorption of protein is facilitated by the release of counterions and the formation of ion pairs between the sorbent and the adsorbate. Lower: A neutral surface (zwitterion or PEG) has no surface ions associated with it. The binding of protein to the surface will not result in a net increase in entropy due to counterion release, and thus adsorption is not preferred. Note that some net charge is still associated with the original surface but is inaccessible due to a steric barrier.

The term counterion evaporation, used to describe ion release from surfaces, unfortunately emphasizes enthalpic contributions.139 As we described recently,128 ion pair formation as the driving force for athermal or net endothermic complexation also involves the release of water molecules hydrating the counterions. Roughly speaking, the net entropy gain would be kT for each ion or water molecule released. For a neutral surface, such as a zwitterion or PEG moiety, the surface charge is internally balanced (zwitterion) or neutral (PEG), and the formation of an ion pair with the adsorbate is unlikely, as no ions are available for release from the surface. Using this rationalization for protein resistance, adsorption can be divided into ion-coupled and ion-decoupled mechanisms. The small value (4 kJ) for the enthalpy of dilution of NaCl allows entropic contributions to dominate when Na+ and Cl– are counterions (i.e., in vivo).

Although adsorption is prevented by a single zwitterion layer, a steric component of this ion-coupled mechanism is also possible. Also shown in Figure 6 are a few isolated negative surface charges with their counterions. Access to these residual charges is blocked by neighboring surface ligands, preventing the release of counterions. One can envisage the same mechanism with oligo or polymeric brushes of neutral polymer. These bulky coatings are probably more effective at blocking access to surface ions.

This ion-exchange mechanism is accessible through quantitative ion equilibria. The adsorption of a charged species at a charged site may be represented as an ion exchange, for example, a negative polymer or protein charge P– adsorbing to a positive site −R+:

| 1 |

The species are depicted with their counterions condensed on (associated with) the charges. The corresponding equilibrium, using concentrations in lieu of activities, would be given by

| 2 |

where RP is the fraction of occupied (by protein) sites and R is the fraction of vacant sites. Or since RP + R = 1, at constant [NaCl], in a Langmuir isotherm format

| 3 |

If the adsorption site on the polymer/protein consists of n charges which adsorb simultaneously

| 4 |

| 5 |

In this case, the isotherm rises more steeply in a so-called high-affinity mode, which is typical for polymers. For simplicity, further analysis is limited to single-charge adsorption (eq 1).

In the absence of specific attractive interactions between −R+ and P–, which should be manifest as negative ΔH, the adsorption is driven by the release of counterions. From eq 2, the adsorbed fraction RP should decrease with increasing salt concentration, which is universally observed in experiments.

In comparison, a zwitterionic site, Z⊕–, has no counterions with which to exchange upon protein adsorption

| 6 |

With no counterions to release, there is no corresponding entropic driving force. In addition, the protein charge is competing with an internal zwitterionic charge at a much higher effective concentration.

| 7 |

K3 is expected to be small, which means that protein adsorption is minimal. In sufficiently concentrated salt, the zwitterion will be forced to take up salt. The internally ion-paired, or intrinsic, form of the zwitterion, Z⊕–, opens up into the extrinsic form, Cl–|⊕Z–|Na+, when it pairs with counterions,

| 8 |

The solution species, P– is now able to exchange with counterions doping the zwitterion and release them

| 9 |

If Z⊕–, ZP, and ⊕Z– are defined, respectively, as the fraction of the zwitterions in intrinsic, protein-paired, and counterion-paired forms and Z⊕– + ZP + ⊕Z– = 1, then

| 10 |

| 11 |

wherein K3 = K1K2. The more resistant to ion pairing, the more effective the zwitterion will be at defeating adsorption. The zwitterion efficiency, defined as K1–1, should be as large as possible (i.e., K1 ≪ 1). The zwitterion efficiency should be a function of various parameters such as the solvent, the salt ions (with those ions on the chaotropic side of the Hofmeister series, such as SCN, I–, and ClO4– showing lower efficiency, i.e. better doping), the zwitterion functional groups, and the distance between them (as n in Figure 1 increases, K1–1 decreases).

An interesting consequence of eq 7, which rearranges to ZP = K3Z⊕–⌊P–Naaq+⌋, is that if the zwitterion efficiency is high and Z⊕– stays close to 1 then ZP is essentially independent of salt concentration, in contrast to a fixed-charge site (eq 2).

Guidelines for Effective Zwitteration

For fouling resistance, polyzwitterions have a lot in common with PEG or, for that matter, any neutral hydrophilic polymer. However, for 2-D coverage a monomeric layer of EG or EG-like units, such as methoxy or OH, is not as effective as a layer of monomeric zwitterion,38 probably due to non-ion-coupled interactions such as hydrogen bonding or hydrophobic interactions in the former.

Three-dimensional or film coverage is expected to be more rugged than for a monolayer: if an area of monolayer is compromised, then fouling resistance fails, whereas a brush or film is able to fill in exposed or damaged areas to some extent. Balanced against ruggedness is an increased size (for nanoparticles), more possibility of contamination if the brush detaches, and slower integration into surroundings (e.g., by endothelialization or coating with a noninflammatory extracellular matrix).

At high NaCl concentration EG units collapse, whereas zwitterion units are well hydrated.86 In fact, it is one of the properties of monomeric or polymeric zwitterions that they become more hydrated as the NaCl concentration increases, a consequence of the equilibrium in eq 8.

It is difficult to quantify the contribution of each mechanism because of entangled enthalpic and entropic components. However, it is possible to summarize qualitatively, as in Table 1, whether each mechanism operates favorably for a 2-D or 3-D coating.

Table 1. Contributions of Various Nonfouling Mechanisms in 2- and 3-D Zwitterionic, ZW, and EG Coatingsa.

| monolayer ZWb | brush polyZW | monolayer EG | brush polyEGc | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| excluded volume | x | √ | x | √ |

| surface energy | √ | √ | x | √ |

| ion coupled adsorption | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| water structuring | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| steric ion coupled effects | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| surface mobility | x | √ | x | √ |

| salt resistance | √ | √ | x | x |

x = little or no contribution, √ = favorable contribution.

ZW = zwitterion.

Includes oligo EG.

Whether perfect nonfouling is needed depends on what type of surface response is sought. In some cases, high-performance nonadsorption at all costs may not really be desirable. Imagine an area of an implant coated with a zwitterion brush which has perhaps been partially hydrolyzed to reveal carboxylic acid groups which in turn activate platelets. The implant remains nonfouled but is now less biocompatible. It may be preferred, in many cases, to integrate without inflammation.

Table 1 shows zwitterion polymers to be the highest performer, with all boxes checked. Zwitterion brushes are bioinspired but not biomimetic (like zwitterion monolayers). If zwitterion brushes are so good at preventing fouling, then why has nature not endowed the cell membrane with them? A cell is not a fortress. A multitude of extracellular macromolecules need to interact in a controlled, specific manner with the cell via its membrane. Nonspecific interactions are discouraged by the zwitterion monolayer. There is a brush component to the cell membrane: the glycocalyx. These are mainly polysaccharides (not zwitterions, their ether linkages place them closer to PEG in structure), and they presumably provide a fine balance between assisting the zwitterion monolayer in repelling nonspecific adsorbers while allowing some access to the membrane and providing specific modes of interaction with themselves via programmed molecular recognition.

Conclusions: Outlook for Zwitteration

The use of zwitterions to protect surfaces is expected to grow, at both sophisticated biological interfaces and at less-well-defined environmental ones. An example of the latter category would be protecting membranes from fouling by particles and organics. Because zwitterion interactions are reduced with exposure to aqueous NaCl, they are ideally suited for physiological or marine conditions and applications. Zwitterionic behavior may be hiding in plain sight. As mentioned earlier, stoichiometric polyelectrolyte complexes, such as those often found in polyelectrolyte multilayers,128 have the requisite functional groups in the right spatial proximity. Such systems may be considered to be bulk zwitterions or zwittersolids.

In nanomedicine, conditions and times used to demonstrate the nonaggregating properties of nanoparticles vary widely. A period of about a day is enough to cover most imaging and therapeutic requirements for targeted and/or diagnostic nanoparticles. Thus, the 24 h time point for stability tests in media approaching serum as closely as possible should be used in screening the effectiveness of coatings designed to promote circulation. The use of a rugged nonaggregating coating should make it easier to discern whether possible nanoparticle toxicity is a result of the NP itself or their aggregates.

In planar systems, short-term use for zwitterated surfaces has significant potential. MPC itself is already approved for in vivo applications.140 Coatings on guidewires and catheters to prevent fouling and bacterial biofilms should be effective for the short term (up to a few weeks). The prospect for long-term in vivo applications of any nonfouling coating is more uncertain. Even biocompatible MPC coatings on coronary stents did not prevent endothelialization in pig models.141 Paradoxically, the same coating that initially reduced biofouling now weakens the interface between the stent and the new tissue, making it prone to mechanical failure. In vivo testing of zwitterated particles and surfaces is urgently needed as is more modeling (simulations, molecular mechanics), which must include water molecules explicitly.

Acknowledgments

The author’s work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

Biography

Joseph B. Schlenoff is Mandelkern Professor of Polymer Science and Distinguished Research Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry at Florida State University. After a brief stint at Polaroid Corporation (Cambridge, MA), he completed a Ph.D. in chemistry at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, in 1987. Following a postdoc in polymer science at UMass, he joined the faculty of FSU in 1988. He has worked on polyelectrolytes at surfaces, in thin films, and in bulk complexes. Other surface science interests include self-assembled monolayers and modifying interactions at the biointerface.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

References

- Callow J. A.; Callow M. E. Trends in the Development of Environmentally Friendly Fouling-resistant Marine Coatings. Nature Commun. 2011, 22441–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobretsov S.; Abed R. M. M.; Teplitski M. Mini-review: Inhibition of Biofouling by Marine Microorganisms. Biofouling 2013, 294423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. F.; Li L. Y.; Zhao C.; Zheng J. Surface Hydration: Principles and Applications Toward Low-fouling/nonfouling Biomaterials. Polymer 2010, 51235283–5293. [Google Scholar]

- Luk Y. Y.; Kato M.; Mrksich M. Self-assembled Monolayers of Alkanethiolates Presenting Mannitol Groups are Inert to Protein Adsorption and Cell Attachment. Langmuir 2000, 16249604–9608. [Google Scholar]

- Howard M. D.; Jay M.; Dziublal T. D.; Lu X. L. PEGylation of Nanocarrier Drug Delivery Systems: State of the Art. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2008, 42133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher M. S.; Raff M. C. Mammalian Plasma-Membranes. Nature 1975, 258553043–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaal R. F. A.; Comfurius P.; Vandeenen L. L. M. Membrane Asymmetry and Blood-Coagulation. Nature 1977, 2685618358–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hub H. H.; Hupfer B.; Koch H.; Ringsdorf H. Polymerizable Phospholipid Analogs - New Stable Biomembrane and Cell Models. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1980, 1911938–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akimoto A.; Dorn K.; Gros L.; Ringsdorf H.; Schupp H. Polyreactions in Oriented Systems 0.23. Polymer Model Membranes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Eng. 1981, 20190–91. [Google Scholar]

- Regen S. L.; Singh A.; Oehme G.; Singh M. Polymerized Phosphatidylcholine Vesicles - Synthesis and Characterization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 1043791–795. [Google Scholar]

- Regen S. L.; Singh A.; Oehme G.; Singh M. Polymerized Phosphatidyl Choline Vesicles - Stabilized and Controllable Time-Release Carriers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1981, 1011131–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umeda T.; Nakaya T.; Imoto M. Polymeric Phospholipid Analogs. The Convenient Preparation of a Vinyl Monomer Containing a Phospholipid Analog. Makromol. Chem. Rapid Commun. 1982, 37457–459. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht O.; Johnston D. S.; Villaverde C.; Chapman D. Stable Biomembrane Surfaces Formed by Phospholipid Polymers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1982, 6872165–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladenheim H.; Morawetz H. A New Type of Polyampholyte - Poly(4-Vinyl Pyridine Betaine). J. Polym. Sci. 1957, 26113251–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hart R.; Timmerman D. New Polyampholytes - the Polysulfobetaines. J. Polym. Sci. 1958, 28118638–640. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade J. D.; Hlady V. Protein Adsorption and Materials Biocompatibility - a Tutorial Review and Suggested Hypotheses. Adv. Polym. Sci. 1986, 79, 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward J. A.; Chapman D. Biomembrane Surfaces as Models for Polymer Design - the Potential for Hemocompatibility. Biomaterials 1984, 53135–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikada Y.; Iwata H.; Horii F.; Matsunaga T.; Taniguchi M.; Suzuki M.; Taki W.; Yamagata S.; Yonekawa Y.; Handa H. Blood Compatibility of Hydrophilic Polymers. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1981, 155697–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal P.; Hall J. B.; McLeland C. B.; Dobrovolskaia M. A.; McNeil S. E. Nanoparticle Interaction with Plasma Proteins as it Relates to Particle Biodistribution, Biocompatibility and Therapeutic Efficacy. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2009, 616428–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi K.; Masuhara E.; Kadoma Y.; Nakabayashi N. 2-Methacryloxyethylphosphorylcholine. Japanese Patent JP 54063025, 1977.

- Nakaya T.; Li Y. J. Phospholipid Polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1999, 241143–181. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A. L. Phosphorylcholine-based Polymers and their Use in the Prevention of Biofouling. Colloids Surf., B 2000, 183–4261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young G.; Bowers R.; Hall B.; Port M. Clinical Comparison of Omafilcon A with Four Control Materials. CLAO J. 1997, 234249–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis S. L.; Court J. L.; Redman R. P.; Wang J. H.; Leppard S. W.; O’Byrne V. J.; Small S. A.; Lewis A. L.; Jones S. A.; Stratford P. W.; Novel Phosphorylcholine-coated A. Contact Lens for Extended Wear Use. Biomaterials 2001, 22243261–3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama K.; Shiraishi K.; Okada K.; Matsuo O. Biocompatible Block Copolymers Composed of Polydimethylsiloxane and Poly[(2-methacryloyloxy)ethyl phosphorylcholine] Segments. Polym. J. 1999, 3110883–886. [Google Scholar]

- Čeh B.; Winterhalter M.; Frederik P. M.; Vallner J. J.; Lasic D. D. Stealth liposomes: from theory to product. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 1997, 242–3165–177. [Google Scholar]

- Immordino M. L.; Dosio F.; Cattel L. Stealth liposomes: review of the basic science, rationale, and clinical applications, existing and potential. Int. J. Nanomed. 2006, 13297–315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senior J. H. Fate and Behavior of Liposomes Invivo - a Review of Controlling Factors. CRC Crit. Rev. Therap. Drug Carrier Syst. 1987, 32123–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox J. H.; Jurand J. Zwitterion-Pair Chromatography of Nucleotides and Related Species. J. Chromatogr. 1981, 203, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hu W. Z.; Haddad P. R. Electrostatic Ion Chromatography. TrAC, Trends Anal. Chem. 1998, 17273–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzo R. G.; Allara D. L. Adsorption of Bifunctional Organic Disulfides on Gold Surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983, 105134481–4483. [Google Scholar]

- Diem T.; Czajka B.; Weber B.; Regen S. L. Spontaneous Assembly of Phospholipid Monolayers Via Adsorption onto Gold. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108196094–6095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabianowski W.; Coyle L. C.; Weber B. A.; Granata R. D.; Castner D. G.; Sadownik A.; Regen S. L. Spontaneous Assembly of Phosphatidylcholine Monolayers Via Chemisorption onto Gold. Langmuir 1989, 5135–41. [Google Scholar]

- Schlenoff J. B.; Li M.; Ly H. Stability and Self-Exchange in Alkanethiol Monolayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 1175012528–12536. [Google Scholar]

- Aldeek F.; Muhammed M. A. H.; Palui G.; Zhan N.; Mattoussi H. Growth of Highly Fluorescent Polyethylene Glycol- and Zwitterion-Functionalized Gold Nanoclusters. ACS Nano 2013, 732509–2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muro E.; Pons T.; Lequeux N.; Fragola A.; Sanson N.; Lenkei Z.; Dubertret B. Small and Stable Sulfobetaine Zwitterionic Quantum Dots for Functional Live-Cell Imaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132134556–4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegoulia V. A.; Rao W. S.; Kalambur A. T.; Rabolt J. R.; Cooper S. L. Surface Properties, Fibrinogen Adsorption, and Cellular Interactions of a Novel Phosphorylcholine-containing Self-assembled Monolayer on Gold. Langmuir 2001, 17144396–4404. [Google Scholar]

- Holmlin R. E.; Chen X. X.; Chapman R. G.; Takayama S.; Whitesides G. M. Zwitterionic SAMs that Resist Nonspecific Adsorption of Protein from Aqueous Buffer. Langmuir 2001, 1792841–2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. F.; Zheng J.; Li L. Y.; Jiang S. Y. Strong Resistance of Phosphorylcholine Self-assembled Monolayers to Protein Adsorption: Insights into Nonfouling Properties of Zwitterionic Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 1274114473–14478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe A. B.; Vamvakaki M.; Wassall M. A.; Wong L.; Billingham N. C.; Armes S. P.; Lloyd A. W. Well-defined Sulfobetaine-based Statistical Copolymers as Potential Antibioadherent Coatings. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2000, 52188–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum D. S.; Olenych S. G.; Keller T. C. S.; Schlenoff J. B. Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells on Polyelectrolyte Multilayers: Hydrophobicity-directed Adhesion and Growth. Biomacromolecules 2005, 61161–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olenych S. G.; Moussallem M. D.; Salloum D. S.; Schlenoff J. B.; Keller T. C. S. Fibronectin and Cell Attachment to Cell and Protein Resistant Polyelectrolyte Surfaces. Biomacromolecules 2005, 663252–3258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisch A.; Voegel J.-C.; Gonthier E.; Decher G.; Senger B.; Schaaf P.; Mésini P. J. Polyelectrolyte Multilayers Capped with Polyelectrolytes Bearing Phosphorylcholine and Triethylene Glycol Groups: Parameters Influencing Antifouling Properties. Langmuir 2009, 2563610–3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou P.; Hartleb W.; Lienkamp K. It Takes Walls and Knights to Defend a Castle - Synthesis of Surface Coatings from Antimicrobial and Antibiofouling Polymers. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 223719579–19589. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. Y.; Armes S. P. Surface Polymerization of Hydrophilic Methacrylates from Ultrafine Silica Sols in Protic Media at Ambient Temperature: A Novel Approach to Surface Functionalization using a Polyelectrolytic Macroinitiator. Adv. Mater. 2003, 15181558–1562. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. A.; Lin W. F.; Chen S. F.; Xu H.; Gu H. C. Development of a Stable Dual Functional Coating with Low Non-specific Protein Adsorption and High Sensitivity for New Superparamagnetic Nanospheres. Langmuir 2011, 272213669–13674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda Y.; Kobayashi M.; Annaka M.; Ishihara K.; Takahara A. Dimensions of a Free Linear Polymer and Polymer Immobilized on Silica Nanoparticles of a Zwitterionic Polymer in Aqueous Solutions with Various Ionic Strengths. Langmuir 2008, 24168772–8778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Giesbers M.; Gerth M.; Zuilhof H. Generic Top-Functionalization of Patterned Antifouling Zwitterionic Polymers on Indium Tin Oxide. Langmuir 2012, 283412509–12517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A. T.; Baggerman J.; Paulusse J. M. J.; van Rijn C. J. M.; Zuilhof H. Stable Protein-Repellent Zwitterionic Polymer Brushes Grafted from Silicon Nitride. Langmuir 2011, 2762587–2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terayama Y.; Kikuchi M.; Kobayashi M.; Takahara A. Well-Defined Poly(sulfobetaine) Brushes Prepared by Surface-Initiated ATRP Using a Fluoroalcohol and Ionic Liquids as the Solvents. Macromolecules 2011, 441104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W.; Irgum K. Covalently Bonded Polymeric Zwitterionic Stationary Phase for Simultaneous Separation of Inorganic Cations and Anions. Anal. Chem. 1999, 712333–344. [Google Scholar]

- Viklund C.; Sjogren A.; Irgum K.; Nes I. Chromatographic Interactions between Proteins and Sulfoalkylbetaine-based Zwitterionic Copolymers in Fully Aqueous Low-salt Buffers. Anal. Chem. 2001, 733444–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W.; Irgum K. Tentacle-type Zwitterionic Stationary Phase, Prepared by Surface-initiated Graft Polymerization of 3-[N,N-dimethyl-N-(methacryloyloxyethyl)-ammonium] Propanesulfonate Through Peroxide Groups Tethered on Porous Silica. Anal. Chem. 2002, 74184682–4687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W.; Fischer G.; Girmay Y.; Irgum K. Zwitterionic Stationary Phase with Covalently Bonded Phosphorylcholine Type Polymer Grafts and its Applicability to Separation of Peptides in the Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography Mode. J. Chromatog., A 2006, 11271–282–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z.-K.; Dai Q.-W.; Wu J.; Huang X.-J.; Yang Q. Covalent Attachment of Phospholipid Analogous Polymers To Modify a Polymeric Membrane Surface: A Novel Approach. Langmuir 2004, 2041481–1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.; Briscoe W. H.; Armes S. P.; Klein J. Lubrication at Physiological Pressures by Polyzwitterionic Brushes. Science 2009, 32359221698–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng W.; Brash J.; Zhu S. P. Atom-transfer Radical Grafting Polymerization of 2-Methacryloyloxyethyl Phosphorylcholine from Silicon Wafer Surfaces. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2004, 42122931–2942. [Google Scholar]

- Feng W.; Zhu S. P.; Ishihara K.; Brash J. L. Adsorption of Fibrinogen and Lysozyme on Silicon Grafted with Poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) via Surface-initiated Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Langmuir 2005, 21135980–5987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata R.; Suk-In P.; Hoven V. P.; Takahara A.; Akiyoshi K.; Iwasaki Y. Control of Nanobiointerfaces Generated from Well-defined Biomimetic Polymer Brushes for Protein and Cell Manipulations. Biomacromolecules 2004, 562308–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Chen S.; Chang Y.; Jiang S. Surface Grafted Sulfobetaine Polymers via Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization as Superlow Fouling Coatings. J. Phys. Chem. B 2006, 1102210799–10804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Finlay J. A.; Wang L. F.; Gao Y.; Callow J. A.; Callow M. E.; Jiang S. Y. Polysulfobetaine-Grafted Surfaces as Environmentally Benign Ultralow Fouling Marine Coatings. Langmuir 2009, 252313516–13521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S.; Cao Z. Ultralow-Fouling, Functionalizable, and Hydrolyzable Zwitterionic Materials and Their Derivatives for Biological Applications. Adv. Mater. 2010, 229920–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd J.; Zhang Z.; Chen S.; Hower J. C.; Jiang S. Zwitterionic Polymers Exhibiting High Resistance to Nonspecific Protein Adsorption from Human Serum and Plasma. Biomacromolecules 2008, 951357–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G.; Zhang Z.; Chen S. F.; Bryers J. D.; Jiang S. Y. Inhibition of Bacterial Adhesion and Biofilm Formation on Zwitterionic Surfaces. Biomaterials 2007, 28294192–4199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso M.; Nguyen A. T.; de Jong E.; Baggerman J.; Paulusse J. M. J.; Giesbers M.; Fokkink R. G.; Norde W.; Schroen K.; van Rijn C. J. M.; Zuilhof H. Protein-Repellent Silicon Nitride Surfaces: UV-Induced Formation of Oligoethylene Oxide Mono layers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 33697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. H.; Chang Y.; Lee K. R.; Wei T. C.; Higuchi A.; Ho F. M.; Tsou C. C.; Ho H. T.; Lai J. Y. Hemocompatible Control of Sulfobetaine-Grafted Polypropylene Fibrous Membranes in Human Whole Blood via Plasma-Induced Surface Zwitterionization. Langmuir 2012, 285117733–17742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang J. H.; Messersmith P. B. Universal Surface-Initiated Polymerization of Antifouling Zwitterionic Brushes Using a Mussel-Mimetic Peptide Initiator. Langmuir 2012, 28187258–7266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q.; Singh A.; Liu L. Amino Acid-Based Zwitterionic Poly(serine methacrylate) as an Antifouling Material. Biomacromolecules 2012, 141226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostina N. Y.; Rodriguez-Emmenegger C.; Houska M.; Brynda E.; Michálek J. Non-fouling Hydrogels of 2-Hydroxyethyl Methacrylate and Zwitterionic Carboxybetaine (Meth)acrylamides. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13124164–4170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q.; Ulbricht M. Novel Membrane Adsorbers with Grafted Zwitterionic Polymers Synthesized by Surface-Initiated ATRP and Their Salt-Modulated Permeability and Protein Binding Properties. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24152943–2951. [Google Scholar]

- Pei Y.; Travas-Sejdic J.; Williams D. E. Reversible Electrochemical Switching of Polymer Brushes Grafted onto Conducting Polymer Films. Langmuir 2012, 28218072–8083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.-S.; Chen Q.; Liu X.; Yuan B.; Wu S.-S.; Shen J.; Lin S.-C. Grafting of Zwitterion from Cellulose Membranes via ATRP for Improving Blood Compatibility. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10102809–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M.; Liu H.; Kilduff J. E.; Langer R.; Anderson D. G.; Belfort G. High-Throughput Membrane Surface Modification to Control NOM Fouling. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43103865–3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doane T. L.; Burda C. The Unique Role of Nanoparticles in Nanomedicine: Imaging, Drug Delivery and Therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 4172885–2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain R. K.; Stylianopoulos T. Delivering Nanomedicine to Solid Tumors. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 711653–664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosaka Y.; Ohta N.; Fukuyama T.; Fujii N. Size Control of Ultrasmall Cds Particles in Aqueous-Solution by Using Various Thiols. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1993, 155123–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bae W.; Mehra R. K. Cysteine-capped ZnS Nanocrystallites: Preparation and Characterization. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1998, 702125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Rogach A. L.; Katsikas L.; Kornowski A.; Su D.; Eychmüller A.; Weller H. Synthesis and characterization of thiol-stabilized CdTe nanocrystals. Ber.-Bunsen. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100111772–1778. [Google Scholar]

- Aryal S.; Bahadur K. C. R.; Bhattarai N.; Kim C. K.; Kim H. Y. Study of Electrolyte Induced Aggregation of Gold Nanoparticles Capped by Amino Acids. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 2991191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal S.; Gole A.; Lala N.; Gonnade R.; Ganvir V.; Sastry M. Studies on the Reversible Aggregation of Cysteine-capped Colloidal Silver Particles Interconnected via Hydrogen Bonds. Langmuir 2001, 17206262–6268. [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. H.; Choi H. S.; Zimmer J. P.; Tanaka E.; Frangioni J. V.; Bawendi M. Compact Cysteine-coated CdSe(ZnCdS) Quantum Dots for In Vivo Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 1294714530–14531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittins D. I.; Caruso F. Spontaneous Phase Transfer of Nanoparticulate Metals from Organic to Aqueous Media. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001, 40163001–3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatumi R.; Fujihara H. Remarkably Stable Gold Nanoparticles Functionalized with a Zwitterionic Liquid Based on Imidazolium Sulfonate in a High Concentration of Aqueous Electrolyte and Ionic Liquid. Chem. Commun. 2005, 1, 83–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouhana L. L.; Jaber J. A.; Schlenoff J. B. Aggregation-resistant Water-soluble Gold Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2007, 232612799–12801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estephan Z. G.; Jaber J. A.; Schlenoff J. B. Zwitterion-Stabilized Silica Nanoparticles: Toward Nonstick Nano. Langmuir 2010, 262216884–16889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estephan Z. G.; Schlenoff P. S.; Schlenoff J. B. Zwitteration As an Alternative to PEGylation. Langmuir 2011, 27116794–6800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouhana L. L.; Schlenoff J. B. Aggregation Resistant Zwitterated Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles. J. Nanopart. Res. 2012, 14, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K.; Watanabe S.; Nakahama S. Emulsion Polymerization of Styrene Using Phospholipid as Emulsifier - Immobilization of Phospholipids on the Latex Surface. Makromol. Chem. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 1989, 19051195–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama K.; Aoki H. Surface-Modified Polymer Microspheres Obtained by the Emulsion Copolymerization of 2-Methacryloyloxyethyl Phosphorylcholine with Various Vinyl Monomers. Polym. J. 1994, 265561–569. [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi K.; Ohnishi T.; Sugiyama K.; Okada K.; Matsuo O. Surface Modified Poly(methyl methacrylate) Microspheres with the O-Methacryloyl-L-serine Moiety. Chem. Lett. 1997, 9, 863–864. [Google Scholar]

- Konno T.; Kurita K.; Iwasaki Y.; Nakabayashi N.; Ishihara K. Preparation of Nanoparticles Composed with Bioinspired 2-methacryloyloxyethyl Phosphorylcholine Polymer. Biomaterials 2001, 22131883–1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida T.; Furuzono T.; Ishihara K.; Nakabayashi N.; Akashi M. Craft Copolymers Having Hydrophobic Backbone and Hydrophilic Branches. XXX. Preparation of Polystyrene-core Nanospheres Having a Poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) Corona. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2000, 38173052–3058. [Google Scholar]

- Jia G. W.; Cao Z. Q.; Xue H.; Xu Y. S.; Jiang S. Y. Novel Zwitterionic-Polymer-Coated Silica Nanoparticles. Langmuir 2009, 2553196–3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson N. S.; Fetters L. J.; Funk W. G.; Graessley W. W.; Hadjichristidis N. Association Behavior in End-functionalized Polymers. 1. Dilute Solution Properties of Polyisoprenes with Amine and Zwitterion End Groups. Macromolecules 1988, 211112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bredas J. L.; Chance R. R.; Silbey R. Head-head Interactions in Zwitterionic Associating Polymers. Macromolecules 1988, 2161633–1639. [Google Scholar]

- Kumacheva E.; Klein J.; Pincus P.; Fetters L. J. Brush Formation from Mixtures of Short and Long End-Functionalized Chains in a Good Solvent. Macromolecules 1993, 26246477–6482. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw D. J.; Huang C. C. Dilute Solution Properties of Poly(3-dimethyl acryloyloxyethyl ammonium propiolactone). Polymer 1997, 38266355–6362. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev G. S.; Karnenska E. B.; Vassileva E. D.; Kamenova I. P.; Georgieva V. T.; Iliev S. B.; Ivanov I. A. Self-assembly, Anti Polyelectrolyte Effect, and Nonbiofouling Properties of Polyzwitterions. Biomacromolecules 2006, 741329–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser H.; Pascher I.; Pearson R. H.; Sundell S. Preferred Conformation and Molecular Packing of Phosphatidylethanolamine and Phosphatidylcholine. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1981, 650121–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buldt G.; Gally H. U.; Seelig J.; Zaccai G. Neutron-Diffraction Studies on Phosphatidylcholine Model Membranes 0.1. Head Group Conformation. J. Mol. Biol. 1979, 1344673–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weers J. G.; Rathman J. F.; Axe F. U.; Crichlow C. A.; Foland L. D.; Scheuing D. R.; Wiersema R. J.; Zielske A. G. Effect of the Intramolecular Charge Separation Distance on the Solution Properties of Betaines and Sulfobetaines. Langmuir 1991, 75854–867. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin R. G. Fundamentals of the Zwitterionic Hydrophilic Group. Langmuir 1991, 75842–847. [Google Scholar]

- Izumrudov V. A.; Domashenko N. I.; Zhiryakova M. V.; Davydova O. V. Interpolyelectrolyte Reactions in Solutions of Polycarboxybetaines, 2: Influence of Alkyl Spacer in the Betaine Moieties on Complexing with Polyanions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 1093717391–17399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.; Liu Z.; Janzen J.; Chafeeva I.; Horte S.; Chen W.; Kainthan R. K.; Kizhakkedathu J. N.; Brooks D. E. Polyvalent Choline Phosphate as a Universal Biomembrane Adhesive. Nat. Mater. 2012, 115468–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.; Yang X.; Horte S.; Kizhakkedathu J. N.; Brooks D. E. ATRP Synthesis of Poly(2-(methacryloyloxy)ethyl choline phosphate): a Multivalent Universal Biomembrane Adhesive. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49616831–6833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L. W.; Hartwick R. A. Zwitterionic Stationary Phases in HPLC. J. Chrom. Sci. 1989, 274176–185. [Google Scholar]

- Salamone J. C.; Volksen W.; Olson A. P.; Israel S. C. Aqueous Solution Properties of a Poly(vinyl imidazolium sulphobetaine). Polymer 1978, 19101157–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M.; Terayama Y.; Kikuchi M.; Takahara A. Chain Dimensions and Surface Characterization of Superhydrophilic Polymer Brushes with Zwitterion Side Groups. Soft Mater. 2013, 9215138–5148. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe A. B.; McCormick C. L. Synthesis and Solution Properties of Zwitterionic Polymers. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102114177–4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu A. Z.; Liaw D. J.; Sang H. C.; Wu C. Light-scattering Study of a Zwitterionic Polycarboxybetaine in Aqueous Solution. Macromolecules 2000, 3393492–3494. [Google Scholar]

- Mahon J.; Zhu S. Interactions of Poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) with Various Salts Studied by Size Exclusion Chromatography. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2008, 286121443–1454. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda Y.; Kobayashi M.; Annaka M.; Ishihara K.; Takahara A. Dimension of Poly(2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine) in Aqueous Solutions with Various Ionic Strength. Chem. Lett. 2006, 35111310–1311. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe A. B.; Billingham N. C.; Armes S. P. Synthesis and Properties of Low-Polydispersity Poly(sulfopropylbetaine)s and Their Block Copolymers. Macromolecules 1999, 3272141–2148. [Google Scholar]

- Hirose E.; Iwamoto Y.; Norisuye T. Chain Stiffness and Excluded-Volume Effects in Sodium Poly(styrenesulfonate) Solutions at High Ionic Strength. Macromolecules 1999, 32258629–8634. [Google Scholar]

- Yashiro J.; Norisuye T. Excluded-volume Effects on the Chain Dimensions and Transport Coefficients of Sodium Poly(styrene sulfonate) in Aqueous Sodium Chloride. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 2002, 40232728–2735. [Google Scholar]

- Miyaki Y.; Einaga Y.; Fujita H. Excluded-Volume Effects in Dilute Polymer Solutions. 7. Very High Molecular Weight Polystyrene in Benzene and Cyclohexane. Macromolecules 1978, 1161180–1186. [Google Scholar]

- Venkataswamy K.; Jamieson A. M.; Petschek R. G. Static and Dynamic Properties of Polystyrene in Good solvents: Ethylbenzene and Tetrahydrofuran. Macromolecules 1986, 191124–133. [Google Scholar]

- Rmaile H. H.; Bucur C. B.; Schlenoff J. B. Polyzwitterions in Polyelectrolyte Multilayers: Formation and Applications. Abstr. Pap. ACS 2003, 225, U621–U621. [Google Scholar]

- Kharlampieva E.; Izumrudov V. A.; Sukhishvili S. A. Electrostatic Layer-by-layer Self-assembly of Poly(carboxybetaine)s: Role of Zwitterions in Film Growth. Macromolecules 2007, 40103663–3668. [Google Scholar]

- Mary P.; Bendejacq D. D. Interactions Between Sulfobetaine-based Polyzwitterions and Polyelectrolytes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 11282299–2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mary P.; Bendejacq D. D.; Labeau M. P.; Dupuis P. Reconciling Low- and High-salt Solution Behavior of Sulfobetaine Polyzwitterions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2007, 111277767–7777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikada Y. Blood-Compatible Polymers. Adv. Polym. Sci. 1984, 57, 103–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi M.; Terayama Y.; Yamaguchi H.; Terada M.; Murakami D.; Ishihara K.; Takahara A. Wettability and Antifouling Behavior on the Surfaces of Superhydrophilic Polymer Brushes. Langmuir 2012, 28187212–7222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlgren M.; Arnebrant T. Protein Adsorption to Solid-Surfaces. Trends Biotechnol. 1991, 96201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southall N. T.; Dill K. A.; Haymet A. D. J. A View of the Hydrophobic Effect. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 1063521–533. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Lin W. F.; Wang Z.; Chen S. F.; Chang Y. Investigation of the Hydration of Nonfouling Material Poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) by Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Langmuir 2012, 28197436–7441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E. F.; Lu J. R.; Brewer J.; Russell J.; Penfold J. The Reduced Adsorption of Proteins at the Phosphoryl Choline Incorporated Polymer-water Interface. Langmuir 1999, 1541313–1322. [Google Scholar]

- Schlenoff J. B.; Rmaile A. H.; Bucur C. B. Hydration Contributions to Association in Polyelectrolyte Multilayers and Complexes: Visualizing Hydrophobicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 1304113589–13597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Q.; He Y.; White A. D.; Jiang S. Difference in Hydration between Carboxybetaine and Sulfobetaine. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 1144916625–16631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisaku T.; Watanabe J.; Konno T.; Takai M.; Ishihara K. Hydration of Phosphorylcholine Groups Attached to Highly Swollen Polymer Hydrogels Studied by Thermal Analysis. Polymer 2008, 49214652–4657. [Google Scholar]

- Kitano H.; Sudo K.; Ichikawa K.; Ide M.; Ishihara K. Raman Spectroscopic Study on the Structure of Water in Aqueous Polyelectrolyte Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 1044711425–11429. [Google Scholar]

- Kitano H.; Imai M.; Sudo K.; Ide M. Hydrogen-Bonded Network Structure of Water in Aqueous Solution of Sulfobetaine Polymers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 1064311391–11396. [Google Scholar]

- Kitano H.; Mori T.; Takeuchi Y.; Tada S.; Gemmei-Ide M.; Yokoyama Y.; Tanaka M. Structure of Water Incorporated in Sulfobetaine Polymer Films as Studied by ATR-FTIR. Macromol. Biosci. 2005, 54314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon S. I.; Lee J. H.; Andrade J. D.; Degennes P. G. Protein Surface Interactions in the Presence of Polyethylene Oxide 0.1. Simplified Theory. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1991, 1421149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Currie E. P. K.; Norde W.; Cohen Stuart M. A. Tethered Polymer Chains: Surface Chemistry and their Impact on Colloidal and Surface Properties. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 100–1020205–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norde W.; MacRitchie F.; Nowicka G.; Lyklema J. Protein Adsorption at Solid-liquid Interfaces: Reversibility and Conformation Aspects. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1986, 1122447–456. [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi K.; Sakiyama T.; Imamura K. On the Adsorption of Proteins on Solid Surfaces, a Common but Very Complicated Phenomenon. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2001, 913233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulikova G. A.; Ryabinina I. V.; Guseynov S. S.; Parfenyuk E. V. Calorimetric Study of Adsorption of Human Serum Albumin onto Silica Powders. Thermochim. Acta 2010, 503–504, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck C.; von Grünberg H. H. Counterion Evaporation. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 636061804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro T.; Takatori Y.; Ishihara K.; Konno T.; Takigawa Y.; Matsushita T.; Chung U. I.; Nakamura K.; Kawaguchi H. Surface Grafting of Artificial Joints with a Biocompatible Polymer for Preventing Periprosthetic Osteolysis. Nat. Mater. 2004, 311829–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A. L.; Tolhurst L. A.; Stratford P. W. Analysis of a Phosphorylcholine-based Polymer Coating on a Coronary Stent Pre- and Post-implantation. Biomaterials 2002, 2371697–1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]