Abstract

Purpose

Insulinomas are rare pediatric tumors for which optimal localization studies and management remain undetermined. We present our experience with surgical management of insulinomas during childhood.

Methods

A retrospective review was performed of patients who underwent surgical management for an insulinoma from 1999 to 2012.

Results

The study included eight patients. Preoperative localization was successful with abdominal ultrasound, abdominal CT, endoscopic ultrasound, or MRI in only 20%, 28.6%, 40%, and 50% of patients, respectively. Octreotide scan was non-diagnostic in 4 patients. For diagnostic failure, selective utilization of 18-Fluoro-DOPA PET/CT scanning, arterial stimulation/venous sampling, or transhepatic portal venous sampling were successful in insulinoma localization. Intraoperatively, all lesions were identified by palpation or with the assistance of intraoperative ultrasound. Surgical resection using pancreas sparing techniques (enucleation or distal pancreatectomy) resulted ina cure inall patients. Postoperative complications included a pancreatic fistula in two patients and an additional missed insulinoma in a patient with MEN-1 requiring successful reoperation.

Conclusions

Preoperative tumor localization may require many imaging modalities to avoid unsuccessful blind pancreatectomy. Intraoperative palpation with the assistance of ultrasound offers a reliable method to precisely locate the insulinoma. Complete surgical resection results in a cure. Recurrent symptoms warrant evaluation for additional lesions.

Keywords: Insulinoma, Intraoperative ultrasound, Localization, Pancreatic tumor, Pancreatectomy children

Insulinomas are insulin-secreting neoplasms that arise from pancreatic beta cells. They are the most common functioning neoplasm of the pancreas with an estimated incidence of 4 per million people [1–3]. Although most insulinomas are solitary and sporadic, 10% occur in the setting of multiple endocrine neoplasia-type 1 (MEN-1) in which multiple tumors may be present [1–4]. Patients with insulinomas often have delayed diagnosis after months of nonspecific episodic symptoms related to underlying hypoglycemia [1]. These symptoms are often grouped into two categories: neurologic or neuroglycopenic symptoms and neurogenic or autonomic nervous system related symptoms. Neurologic symptoms include diplopia, behavioral changes, confusion, fatigue, amnesia, seizures and even death if hypoglycemia persists for a long time. The increased release of catecholamines related to the hypoglycemic stimulation of the autonomic nervous system results in hunger, sweating, anxiety, paresthesias, palpitations and other cholinergic and adrenergic symptoms [2,4]. Diagnosis of an insulinoma is confirmed by a 72-hour fast study during which the patient is symptomatic and has inappropriately elevated insulin levels despite hypoglycemia with no evidence of exogenous insulin administration [4].

Once diagnosed, insulinomas are poorly managed medically, and surgical resection provides the only possibility for cure [1,3–5]. The majority of insulinomas are benign with only a 6% incidence of malignancy, and long term survival for nonmalignant disease following surgical resection is 88% in adults [3]. Instrumental to the successful management of a patient with an insulinoma is accurate preoperative and intraoperative localization of the tumor. Multiple studies have been performed in adults evaluating the sensitivity of both invasive and noninvasive preoperative localization techniques [4,6–10]. Additional studies have assessed the role of intraoperative ultrasound and palpation in tumor localization [4–6]. These studies highlight the numerous options available as well as the difficulty in localizing insulinomas.

The median age of presentation of patients with an insulinoma is the late fifth to early sixth decade of life and thus virtually all studies focus on the diagnosis and management of insulinomas in adults [1,3]. The incidence of insulinoma in children is low with only a few case reports in the literature [11–16]. As such, little information exists regarding the surgical management of children diagnosed with an insulinoma as well as the usefulness of various tumor localization techniques during childhood. We reviewed the management of eight children diagnosed with an insulinoma over the past thirteen years at our institution with a focus on the preoperative localization studies, the surgical management including intraoperative tumor localization and resection, and the postoperative course.

1. Materials and methods

This retrospective review of all cases involving the surgical management of an insulinoma in the Congenital Hyperinsulinism Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) from 1999 to 2012 was approved by the CHOP Institutional Review Board, Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (IRB 12–009293). The initial patient population reviewed included children referred to the Congenital Hyperinsulinism Center at CHOP for evaluation of hypoglycemia. Inclusion criteria for this study included 1) the presence of fasting (up to 72 hours) or post-prandial hypoglycemia (defined as a blood glucose less than 50 mg/ dL) in the setting of a detectable insulin level with suppressed beta-hydroxybutyrate and a glycemic response to glucagon, and 2) the histologic confirmation of the diagnosis of an insulinoma following surgical resection. The preoperative evaluation including radiographic imaging and invasive testing as well as surgical management and postoperative course until the time of discharge was reviewed for all patients. Patients received one or some of the following preoperative imaging studies: abdominal CT, arterial stimulation with venous sampling (ASVS), octreotide scan, endoscopic U/S, abdominal MRI, abdominal U/S, transhepatic portal venous sampling (THPVS), or 18 Fluoro-DOPA PET/CT scan. Evaluation by 18 Fluoro-DOPA PET/CT scan was available for patients presenting after 2004 (all patients except patient 1, Table 1). Invasive imaging techniques were employed to clarify findings on noninvasive studies or if noninvasive studies failed to demonstrate a lesion. All patients had a complete intraoperative exploration of the pancreas via a transverse supraumbilical laparotomy. Cure following surgical resection was defined as normal glucose levels in the setting of fasting without either pharmacologic assistance or the need for supplemental glucose at the time of discharge from the hospital. Those patients considered cured and without the concern for MEN-1 did not require specific Endocrine follow-up.

Table 1.

Patient demographics.

| Patient | Sex | Age at diagnosis (years) | Duration between symptom presentation and surgery (months) | Attempted medical management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 4 | 3 | Diazoxide |

| 2 | Male | 8 | 5 | Diazoxide/octreotide |

| 3 | Male | 9 | 84 | Diazoxide |

| 4 | Male | 11 | 4 | None |

| 5 | Female | 5 | 6 | Diazoxide |

| 6 | Male | 14 | 1 | None |

| 7 | Male | 11 | 1.5 | Diazoxide/octreotide |

| 8 | Male | 26 | 2.5 | Diazoxide |

2. Results

2.1. Patients

Eight patients were identified who presented with hypoglycemia in the setting of elevated insulin levels. There were six males and two females in the age range of 4–26 years of age (mean: 11 years; median: 10 years). All patients underwent an extensive preoperative evaluation with subsequent surgical resection and pathological confirmation of the diagnosis of an insulinoma, thus meeting inclusion criteria for the study. The time from initial presentation of symptoms consistent with hypoglycemia to diagnosis and surgical management varied from 1 month to 84 months (mean: 13.4 months; median: 3.5 months) (Table 1). During the time between symptomatic presentation and surgical management, medical management with diazoxide and/or octreotide was attempted in 6 of 8 patients without consistent improvement in blood glucose levels in any patient.

2.2. Preoperative evaluation

After presentation with hypoglycemia in the setting of elevated insulin levels, all patients underwent an extensive preoperative work-up in an attempt to locate a suspected insulinoma. Multiple radiographic imaging techniques, both noninvasive and invasive, were performed (Table 2). The usefulness of different tests varied between patients as exemplified by the ability of some imaging modalities to identify an insulinoma in some patients but not in others (Table 3). Abdominal ultrasound, abdominal CT, endoscopic ultrasound (U/S), or MRI successfully localized an insulinoma in 20%, 28.6%, 40% and 50% of the cases respectively in which they were utilized. For patients with diagnostic failure, 18-Fluoro-DOPA PET/CT scanning, arterial stimulation with venous sampling (ASVS), or transhepatic portal venous sampling (THPVS) were uniformly successful in insulinoma localization. A preoperative octreotide scan was unable to locate an insulinoma in any of the 4 cases in which this modality was attempted. Of note, an insulinoma was not identified by abdominal or endoscopic U/S, abdominal CT, or octreotide scan in patient 7 who has MEN-1 including a history of multiple insulinoma resections 2 years previously at another institution, a known pituitary microadenoma, a family history of parathyroidectomy in his father, and heterozygosity for the W126X mutation in the MEN-1 gene. As such, this patient underwent exploratory laparotomy despite negative preoperative imaging as detailed below.

Table 2.

Preoperative localization studies.

| Patient | Modalities applied | Modalities with successful localization |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CT, Octreotide Scan, ASVS | ASVS |

| 2 | Octreotide Scan, Endoscopic U/S, MRI, Abdominal U/S, 18 F-DOPA PET/CT scan, CT |

Endoscopic U/S, MRI, Abdominal U/S, CT, 18 F-DOPA PET/CT scan |

| 3 | Octreotide Scan, MRI, CT, Endoscopic U/S | Endoscopic U/S |

| 4 | Abdominal U/S, CT | CT |

| 5 | MRI, 18 F-DOPA PET/CT scan |

18 F-DOPA PET/CT scan |

| 6 | MRI, Abdominal U/S, Endoscopic U/S, CT, 18 F-DOPA PET/CT scan | 18 F-DOPA PET/CT scan |

| 7a | Abdominal U/S, Endoscopic U/S, CT, Octreotide Scan | none |

| 7b | MRI, THPVS | MRI, THPVS |

| 8 | Abdominal U/S, CT, Endoscopic U/S, MRI | MRI |

U/S, ultrasound; CT, abdominal CT; ASVS, arterial stimulation with venous sampling; THPVS, transhepatic portal venous sampling.

7a refers imaging studies patient 7 had prior to the initial operation and 7b refers to imaging studies performed prior to the reoperation.

Table 3.

The success of preoperative imaging studies.

| Imaging study | # Successful cases of localization/ total # of times study performed |

|---|---|

| CT | 2/7 (28.6%) |

| ASVS | 1/1 (100%) |

| Octreotide scan | 0/4 (0%) |

| Endoscopic U/S | 2/5 (40%) |

| MRI | 3/6 (50%) |

| 18 F-DOPA PET/CT scan | 3/3 (100%) |

| Abdominal U/S | 1/5 (20%) |

| THPVS | 1/1 (100%) |

CT, abdominal CT; ASVS, arterial stimulation with venous sampling; THPVS, transhepatic portal venous sampling.

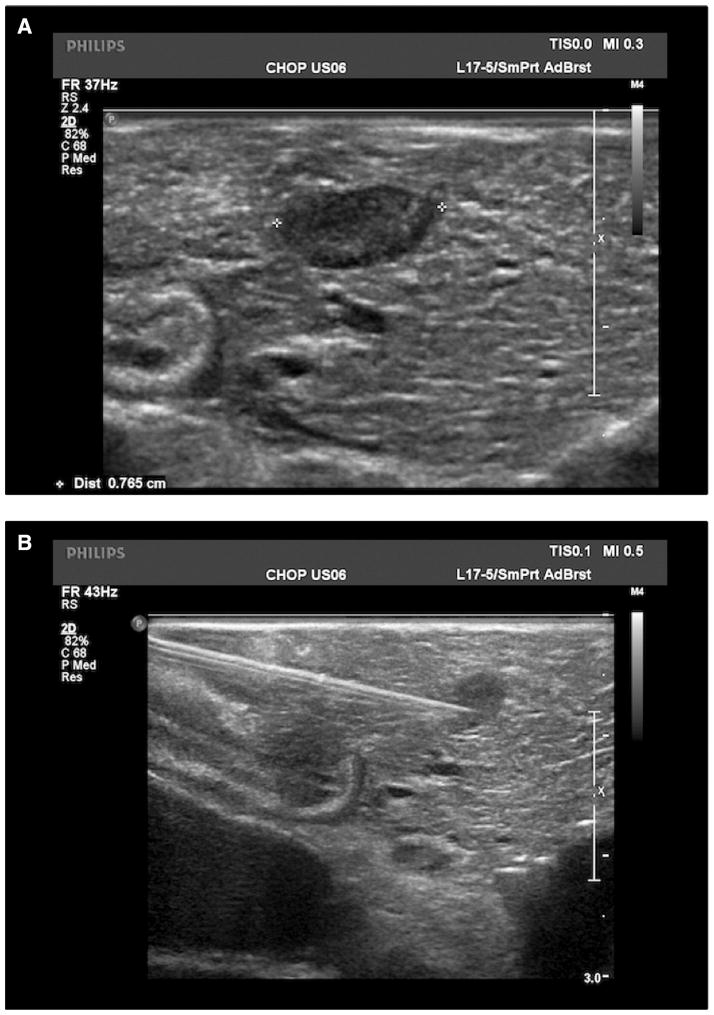

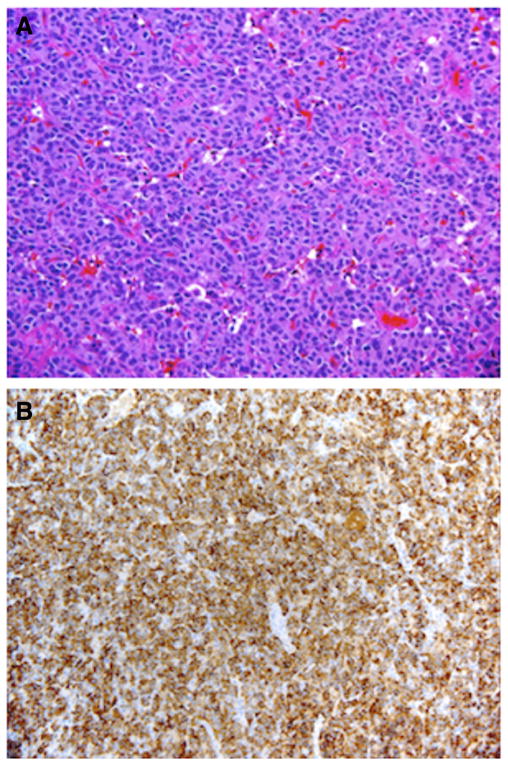

2.3. Surgical management and postoperative course

After an extensive preoperative evaluation including MEN-1 genetic screening (Table 2), all patients underwent exploratory laparotomy and evaluation of the pancreas for the presence of an insulinoma (Table 4). Patients 2 and 7 had previous pancreatic resections for suspected insulinomas at other institutions prior to presenting to CHOP. Patient 2 had a previous pancreaticoduodenectomy in which pathology demonstrated normal pancreas without evidence of an insulinoma. Patient 7 had a previous distal pancreatectomy to remove three insulinomas. Intraoperative palpation identified the lesion in all cases with the exception of our first operation in patient 7. In cases in which palpation of the lesion was difficult (patient 6) or not possible (patient 7), the insulinoma was found by intraoperative U/S and needle localization (Fig. 1). In all patients in which a lesion was identified on preoperative imaging, the intraoperative location of the insulinoma corresponded with the preoperative imaging. Lesions were found in the head (N = 3), neck (N = 1), body (N = 1), and tail (N = 5) of the pancreas and one lesion was partially embedded in the spleen. We used a pancreas sparing approach. All lesions were excised in their entirety either by enucleation or distal pancreatectomy. Efforts were made to minimize the occurrence of post-operative pancreatic leaks by the application of a fibrin sealant (Tisseel; Baxter Healthcare Corporation; Deerfield, IL) (patients 1–3) or placement of a mattress stitch (patients 7 and 8) at the site of enucleation. Pancreatic transection for distal pancreatectomies were performed with an endoscopic GIA stapler (Ethicon Endo-Surgery; Blue Ash, OH). Resected specimens measured from 0.3 cm to 1.8 cm in maximum diameter, and histologic sections demonstrated features typical of well-differentiated pancreatic endocrine neoplasms (insulinomas) including diffuse, lobular to trabecular proliferation of neuroendocrine cells with round to oval nuclei and granular chromatin. Immunostains for synaptophysin and/or chromogranin and insulin were diffusely positive within neoplastic cells in all patients (Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Surgical management and postoperative course.

| Patient | Successful intraop palpation | Successful intraop ultrasound | Tumor location | Surgery | Lesion size | MEN-1 | LOS (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | N/A | Head | Enucleation | 0.7 cm | Negative | 13 |

| 2 | Yes | N/A | Tail | Enucleation | 1.5 cm | Negative | 10 |

| 3 | Yes | N/A | Head | Enucleation | 1.5 cm | Negative | 52 |

| 4 | Yes | N/A | Tail | Distal pancreatectomy | 1.5 cm | Negative | 11 |

| 5 | Yes | N/A | Tail | Distal pancreatectomy | 1.2 cm | Negative | 11 |

| 6 | Yes | Yes | Neck | Enucleation | 0.7 cm | Negative | 17 |

| 7a | No | Yes | 3 microadenomas in head, body & tail | Distal pancreatectomy & enucleation | 0.3 cm | Positive | 67 |

| 7b | Yes | N/a | Splenic hilum | Enucleation | 1.1 cm | 10 from second surgery | |

| 8 | Yes | N/A | Tail | Enucleation | 1.8 cm | Negative | 69 |

N/A indicates in intraoperative U/S was not attempted.

7a and 7b indicate the initial and repeat operations respectively required for a missed lesion after the initial operation on patient 7 at our institution. lesion size refers to the maximal dimension of the insulinoma measured in pathology following resection.

LOS refers to the length of hospital stay postoperatively measured in days. LOS for patient 7a refers to the number of days between the initial surgery and re-exploration. LOS for patient 7b refers to the length of hospital stay following the second surgery resulting in complete surgical excision of the insulinoma in patient 7.

Fig. 1.

Intraoperative ultrasound of the pancreas is used to identify a well circumscribed, hypoechoic lesion measuring 0.77 cm (A). Needle localization under intraoperative ultrasound guidance allows for the excision of a lesion that was not easily palpable (B).

Fig. 2.

Well-differentiated pancreatic endocrine neoplasm (insulinoma) showing solid proliferation of neuroendocrine cells, H&E ×200 original magnification (A); diffuse immunoreactivity for insulin, insulin IHC ×200 original magnification (B).

Postoperative complications included two pancreatic fistulas (patients 3 and 8) and reexploration for a missed lesion and subsequent splenic infarct (patient 7). The fistula from the pancreatic head lesion enucleation for patient 3 was successfully managed with percutaneous drainage of the peripancreatic fluid collection and 14 days of octreotide treatment followed by an ERCP sphincterotomy and pancreatic stent placement. The fistula from the pancreatic tail lesion enucleation for patient 8 was unsuccessfully managed by ERCP with stent placement and percutaneous drainage of the peripancreatic fluid collection, so a distal pancreatectomy with oversewing of the pancreatic resection site was required. At initial exploration at CHOP after a previous distal pancreatectomy at another hospital, patient 7, who has MEN-1, had two glucagonomas and an insulinoma excised by a combination of enucleation of lesions and a spleen-sparing distal pancreatic resection. Postoperatively, he had persistent hypoglycemia, and an MRI showed a suspicious lesion buried in the splenic hilum. An insulinoma was confirmed by elevated insulin levels from this area on transhepatic portal venous sampling. Surgical reexploration demonstrated a palpable lesion measuring 1.1 cm which was partially embedded in the spleen and adherent to the splenic vein and artery. This insulinoma was enucleated, a partial splenic infarction occurred, and postoperatively the patient’s sugars normalized. Hematologic testing demonstrated functional asplenia, so he has been maintained on penicillin prophylaxis.

The mean and median lengths of stay after surgery were 31 and 15 days respectively. Taking into consideration that patient 7 required a second operation for a missed lesion, the mean and median length of stay following complete surgical resection of the insulinoma(s) were 24 and 12 days respectively. All patients underwent a fasting glucose study postoperatively. Following complete excision of the insulinomas, all patients demonstrated appropriate glucose and beta-hydroxybutyrate levels while fasting and were discharged from the hospital without the need for supplemental glucose or pharmacologic management for hypoglycemia.

3. Discussion

Although insulinomas are the most common functioning neoplasms of the pancreas, they predominantly present in adulthood and are rare in children. Our report is the most extensive in the literature focusing on the presentation and surgical management of childhood insulinomas. The study highlights that there is often a delay between the onset of symptoms and subsequent diagnosis and treatment. This is similar to the adult literature in which the mean and median times between presentation and management are 19–50 months and 18 months respectively [1,2,6]. Case series in adults cite a cure rate of 75–98% following surgical excision, and we found complete surgical excision was associated with normoglycemia without the need for supplemental glucose or pharmacologic management in all patients [1,4,17]. The failure of diazoxide or octreotide treatment to provide adequate relief of hypoglycemia in our patients corroborates other studies which have shown that medical management of insulinoma patients has very limited success but may allow for symptomatic control during preoperative evaluation to localize the tumor [2,18].

All patients in our study underwent an extensive preoperative work-up to localize the tumor. The insulinoma was successfully located in 89% (8/9) of cases after multiple modes of imaging techniques were applied. However, an abdominal U/S, abdominal CT scan, MRI, or endoscopic U/S successfully located the lesion in 50% or fewer of patients. Of note, gastroenterologists at The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania who have significant experience with endoscopic ultrasounds performed this study. Thus, we believe that the decreased efficiency of this technique in the pediatric population compared to adult studies in which endoscopic U/S can localize the lesion in greater than 90% of cases may reflect a difference in the usefulness of an endoscopic U/S in the two different patient populations and is not related to the lack of expertise of those performing the study [9,19]. When these diagnostic studies failed to definitively locate the insulinoma, we found that 18 F-DOPA PET/CT scan, THPVS, and ASVS successfully localized the insulinoma in all five patients in which these studies were used. However, the limited number of patients who underwent these studies makes the usefulness of the universal application of these localizing modalities questionable particularly given the specific resource requirements needed to perform these studies as well as the invasive nature and associated complications of a THPVS or ASVS study [2,7,8,20]. We have had significant success with the ability of 18 F-DOPA PET/CT scan to diagnose and localize focal lesions causing congenital hyperinsulinism, and thus, if there is diagnostic uncertainty regarding an insulinoma, we currently use this modality under an Investigational New Drug (IND) protocol reviewed by the Institutional Review Board, Radiation Safety committee and Food and Drug administration [21,22]. We no longer use ASVS avoiding its associated angiographic complications and only rarely use THPVS. In contrast to these studies, an octreotide scan failed to locate an insulinoma in any patient. The low level or lack of expression of the somatostatin receptor on insulinomas supports the limited utility of octreotide scans in the preoperative workup of patients with a suspected insulinoma [23]. Studies performed in adults also suggest that no specific preoperative localization study is uniformly successful. Recent advances in endoscopic U/S and noninvasive imaging suggest that an insulinoma can be identified preoperatively using a combination of these techniques in 90% or more of adult cases [1,9,19]. This compares favorably to older reports supporting the ability to detect an insulinoma using THPVS or ASVS in greater than 90% of patients and argues for the use of these invasive techniques only after noninvasive techniques have failed [7,8].

We believe that all attempts should be made to detect the location of the insulinoma preoperatively, but if preoperative localization is not definitive or not fruitful, intraoperative palpation and ultrasound are useful means of tumor detection. In the adult literature, these modalities have detected 65%–90% and 93%–100% of tumors respectively [2,4–6,10]. We found that the lesion could be palpated in eight of the nine surgeries. Intraoperative U/S was performed in 2 cases, one in which no lesion was palpable but a total of 3 lesions were identified by U/S (1 insulinoma and 2 glucagonomas), and one case in which the lesion was small (7 mm) and intraoperative palpation was difficult. Intraoperative U/S can provide the additional potential benefits of needle localization of the lesion, determination of the course of the main pancreatic duct in relation to the insulinoma, confirmation that the lesion has been completely excised, and examination of the remainder of the pancreas for potential other insulinomas.

The importance of accurate identification of the tumor, either preoperatively or with intraoperative techniques, has been underscored in the adult literature which suggests that blind pancreatic resection for insulinomas is ill advised [1,24]. These studies suggest that the majority of tumors unable to be identified likely originate in the pancreatic head. Thus, a blind distal pancreatectomy, which has been previously suggested, results in inadequate tumor removal. Similarly, a pancreaticoduodenectomy had been performed at another institution in patient 2 but pathology was normal, and the insulinoma proved to be in the pancreatic tail.

Consistent with the adult literature, we found insulinomas in children distributed throughout the pancreas without a predilection for a specific anatomic site [1]. We employed a pancreas sparing approach in the management of our patients and thus attempted enucleation in all cases in which injury to the main pancreatic duct did not seem likely. Following enucleation inspection of the resection site under 3.5× loupe magnification for evidence of a pancreatic duct leak was performed. If a concern existed for a pancreatic leak or pancreatic duct injury, a pancreatectomy would then be considered. Enucleation was accomplished in 5 of 8 cases, a distal pancreatectomy was performed in 2 of 8 cases, and one case required a combination of a distal pancreatectomy and enucleation of lesions in the head and body. This is consistent with the literature in which enucleation was performed in 34–54% of cases and was the procedure of choice in the absence of possible injury to the main pancreatic duct or when malignancy was not suspected [1,4,25]. None of the patients in the current series had a malignant insulinoma which is rare (<10% of insulinomas) but may require a more extensive resection and even liver transplantation secondary to lymph node involvement, invasion into adjacent structures or liver involvement [26]. The spleen can be preserved in patients undergoing a distal pancreatectomy as advised by reports suggesting patients undergoing spleen-preserving procedures have less postoperative complications including infection [4,27]. Although no patients required a pancreaticoduodenectomy in our series, it has been required in 5.5% to 16% of cases involving pancreatic head tumors in which main pancreatic duct injury is a concern [1,25]. All pancreatic head lesions (N = 3) in our study were removed via enucleation. An alternative technique to pancreaticoduodenectomy is pancreatic head resection with Roux-en-Y pancreaticojejunostomy to spare the duodenum and the normal pancreatic body and tail as we have demonstrated in more than 25 neonatal cases of the focal form of congenital hyperinsulinism with extensive pancreatic head involvement [28].

All procedures in the current study were performed via a laparotomy. Advances in laparoscopic techniques have resulted in recent studies proposing the use of laparoscopic enucleation or pancreatectomy with or without intraoperative ultrasound for the management of insulinomas in adults [29–32]. Although these studies are encouraging, we prefer laparotomy for the management of insulinomas in children for a number of reasons. The limited evidence supporting the accuracy of preoperative localization studies in children as well as the critical role of intraoperative palpation and intraoperative ultrasound in identifying the lesions in 89% of cases in the current study highlight the importance of pancreatic exploration via a laparotomy. Additionally, multiple insulinomas are more frequently found in patients with MEN-1 and patients with MEN-1 and insulinomas present at a younger age [4,25]. We believe it is important to explore and palpate the entire pancreas and use intraoperative ultrasound to avoid missing lesions.

In our case series, there was no mortality and some morbidity. Two patients (25%) developed a pancreatic fistula postoperatively. Both patients had undergone an enucleation of the insulinoma, one in the pancreatic head and one in the pancreatic tail. One was managed with percutaneous drainage and pancreatic stent placement whereas that approach failed in the second patient so a distal pancreatectomy was needed to treat the fistula. Our current protocol to minimize the risk of a postoperative pancreatic fistula following enucleation is the application of a fibrin sealant and/or a mattress stitch to the site of resection. Similarly, adult series have shown a 23.7% incidence of a clinically significant postoperative pancreatic leak following surgery for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors with no significant difference between lesions managed via enucleation or pancreatic resection [33]. Another complication was a missed lesion in the splenic hilum requiring reoperation for persistent hypoglycemia in a patient with MEN-1. The presence of MEN-1 is associated with a higher incidence of multiple lesions. 80% of patients with MEN-1 and hyper-insulinemia are noted to have multiple pancreatic tumors [4,25]. In addition, patients with MEN-1 and insulinomas are noted to have a higher rate of malignancy, larger tumor size, and a higher rate of lymphovascular invasion [25]. Although recurrence is possible in the absence of MEN-1, the risk of recurrence is greater in adult patients with MEN-1 than in those without it (21% vs. 5% at 10 years respectively) [3]. The single patient in the current study with MEN-1 did have multiple lesions and his referral to our institution was for management of a recurrence after having had a previous surgical resection 2 years earlier. His pathology, however, was consistent with a benign insulinoma.

We demonstrate that there is frequently a delay between patient symptoms, and diagnosis and surgical management. Surgical excision can provide a cure with minimal morbidity. Crucial to efficient management of a child with an insulinoma is the preoperative and intraoperative localization of the tumors. We now prefer that radiologic evaluation begin with MRI and endoscopic ultrasound, and we reserve 18 F-DOPA PET/CT scan for cases in which those studies are negative. These preoperative techniques used in conjunction with a thorough intraoperative exploration including palpation of the entire pancreas and the availability of intraoperative U/S provide the ability to locate 100% of the lesions. If hypoglycemia persists despite surgical management, one must be cognizant of the possibility a missed or recurrent lesion requiring repeat surgical exploration.

References

- 1.Nikfarjam M, Warshaw AL, Axelrod L, et al. Improved contemporary surgical management of insulinomas. A 25-year experience at the Massachusetts General Hospital. Ann Surg. 2008;247:165–72. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31815792ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant CS. Insulinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:783–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Service FJ, McMahon MM, O’Brien PC, et al. Functioning insulinoma-incidence, recurrence, and long-term survival of patients: a 60 year study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:711–9. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tucker ON, Crotty PL, Conlon KC. The management of insulinoma. Br J Surg. 2006;93:264–75. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiramoto JS, Feldstein VA, LaBerge JM, et al. Intraoperative ultrasound and preoperative localization detects all occult insulinomas. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1020–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.9.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravi K, Britton BJ. Surgical approach to insulinomas: are pre-operative localization tests necessary? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:212–7. doi: 10.1308/003588407X179008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinik AI, Delbridge L, Moattari R, et al. Transhepatic portal vein catheterization for localization of insulinomas: a ten-year experience. Surgery. 1991;109:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiesli P, Brandle M, Schmid C, et al. Selective arterial calcium stimulation and hepatic venous sampling in the evaluation of hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia: potential and limitations. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:1251–6. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000140638.55375.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson MA, Carpenter S, Thompson NW, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound is highly accurate and directs management in patients with neuro-endocrine tumors of the pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2271–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung JC, Choi SH, Jo SH, et al. Localization and surgical treatment of the pancreatic insulinomas. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:1051–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jaksic T, Thorner YP, Wesson DK, et al. A 20 year review of pediatric pancreatic tumors. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:1315–7. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(92)90284-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfsdorf JI, Senior B. The diagnosis of insulinoma in a child in the absence of fasting hyperinsulinemia. Pediatrics. 1979;64:496–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strong VE, Shifrin A, Inabnet WB. Rapid intraoperative insulin assay: a novel method to differentiate insulinoma from nesidioblastosis in the pediatric patient. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2007;24:1–6. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ide S, Uchida K, Inoue M, et al. Tumor enucleation with preoperative endoscopic transpapillary stenting for pediatric insulinoma. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012;28:707–9. doi: 10.1007/s00383-012-3104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonfig W, Kann P, Rothmund M, et al. Recurrent hypoglycemic seizures and obesity: delayed diagnosis of an insulinoma in a 15 year-old boy-final diagnostic localization with endosonography. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2007;20:1035–8. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2007.20.9.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grosfeld JL, Vane DW, Rescorla FJ, et al. Pancreatic tumors in childhood: analysis of 13 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:1057–62. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(90)90218-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doherty GM, Doppman JL, Shawker TH, et al. Results of a prospective strategy to diagnose, localize, and resect insulinomas. Surgery. 1991;110:989–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goode PN, Farndon JR, Anderson J, et al. Diazoxide in the management of patients with insulinoma. World J Surg. 1986;10:586–92. doi: 10.1007/BF01655532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLean AM, Fairclough PD. Endoscopic ultrasound in the localization of pancreatic islet cell tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;19:177–93. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson JE. Angiography and arterial stimulation venous sampling in the localization of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;19:229–39. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laje P, States LJ, Zhuang H, et al. Accuracy of PET/CT scan in the diagnosis of the focal form of congenital hyperinsulinism. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:388–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardy OT, Hernandez-Pampaloni M, Saffer JR, et al. Accuracy of [18 F]flurorodopa positron emission tomography for diagnosing and localizing focal congenital hyperinsulinism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4706–11. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Virgolini I. Nuclear medicine in the detection and management of pancreatic islet-cell tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;19:213–27. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirshberg B, Libutti SK, Alexander HR, et al. Blind distal pancreatectomy for occult insulinoma, an inadvisable procedure. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:761–4. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crippa S, Zerbi A, Boninsegna L, et al. Surgical management of insulinomas-short term and long term outcomes after enucleations and pancreatic resections. Arch Surg. 2012;147:261–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Janem W, Sultan I, Ajlouni F, et al. Malignant insulinoma in a child. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55:1423–6. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shoup M, Brennan MF, McWhite K, et al. The value of splenic preservation with distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 2002;137:164–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laje P, Stanley CA, Palladino AA, et al. Pancreatic head resection and roux-en-Y pancreaticojejunostomy for the treatment of the focal form of congenital hyperinsulinism. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:130–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mabrut JY, Fernandez-Cruz L, Azagra JS, et al. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: results of a multicenter European study of 127 patients. Surgery. 2005;137:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goletti O, Celona G, Monzani F, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of pancreatic insulinoma. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1499. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-4273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaroszewski DE, Schlinkert RT, Thompson GB, et al. Laparoscopic localization and resection of insulinomas. Arch Surg. 2004;139:270–4. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roland CL, Lo CY, Miller BS, et al. Surgical approach and perioperative complications determine short term outcomes in patients with insulinoma: results of a biinstitutional study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3532–7. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0157-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inchauste SM, Lanier BJ, Libutti SK, et al. Rate of clinically significant postoperative pancreatic fistula in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. World J Surg. 2012;36:1517–26. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1598-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]