Abstract

Purpose

To present our experience in the care of infants with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome (BWS) who required pancreatectomy for the management of severe Congenital Hyperinsulinism (HI).

Methods

We did a retrospective chart review of patients with BWS who underwent pancreatectomy between 2009 and 2012.

Results

Four patients with BWS and severe HI underwent pancreatectomy, 3 females and one male. Eight other BWS patients with HI could be managed medically. The diagnosis of BWS was established by the presence of mosaic 11p15 loss of heterozygosity and uniparental disomy in peripheral blood and/or pancreatic tissue. All patients had hypoglycemia since birth that did not respond to medical management with diazoxide or octreotide, and required glucose infusion rates of up to 30 mg/kg/min. Preoperative 18-F-DOPA PET/CT scans showed diffuse uptake of the radiotracer throughout an enlarged pancreas in three patients and a normal sized pancreas with a large area of focal uptake in the pancreatic body in one patient. None of the patients had mutations in the ABCC8 or KCNJ1 genes that are typically associated with diazoxide-resistant HI. Age at surgery was 1, 2, 4, and 12 months and the procedures were 85%, 95%, 90%, and 75% pancreatectomy, respectively, with the pancreatectomy extent tailored to HI severity. Pathologic analysis revealed marked diffuse endocrine proliferation throughout the pancreas that occupied up to 80% of the parenchyma with scattered islet cell nucleomegaly. One patient had a small pancreatoblastoma in the pancreatectomy specimen. The HI improved in all cases after the pancreatectomy, with patients being able to fast safely for more than 8 h. All patients are under close surveillance for embryonal tumors. One patient developed a hepatoblastoma at age 2.

Conclusion

The pathophysiology of HI in BWS patients is likely multifactorial and is associated with a dramatic increase in pancreatic endocrine tissue. Severe cases of HI that do not respond to medical therapy improve when the mass of endocrine tissue is reduced by subtotal or near-total pancreatectomy.

Keywords: Congenital Hyperinsulinism, Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome, Pancreatectomy

Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome is a genetic disorder with a complex molecular basis characterized by an abnormal overgrowth of organs and tissues [1,2]. The hallmark clinical features of the syndrome are macroglossia, omphalocele and gigantism, but the presentation is highly variable and may not include all of those three components. BWS was described for the first time in 1963 by Beckwith, and in 1964 Wiedemann reported the second series of patients with similar features [3,4]. Beckwith’s original report included 3 patients, all of whom had pancreatic enlargement with histological evidence of endocrine hyperplasia. He suggested that the pancreatic endocrine hyperplasia might have caused hypoglycemia (glucose levels had not been obtained). His endocrinology colleagues were coincidentally following two patients with overgrowth, macroglossia, umbilical abnormalities, and a history of severe neonatal hypoglycemia which Beckwith included in a subsequent report [5].

Approximately 50% of patients with BWS develop hypoglycemia at birth [6,7]. The pathophysiologic mechanisms behind this phenomenon are not well understood, but hyperinsulinism (HI) is frequently observed in these patients. In the majority of cases the hypoglycemia is mild, medically manageable, and resolves spontaneously within the first week of life. However, about 4% of BWS patients have hypoglycemia that extends beyond one month of age and requires intensive medical management and even surgery [7]. We present our experience with BWS patients who required pancreatectomy for the management of severe HI.

1. Materials and methods

After obtaining Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, we did a retrospective chart review of patients with BWS who underwent pancreatectomy at our institution between 2009 and 2012.

The medical management of patients with hyperinsulinism consists of a combination of hyperglycemic medications (diazoxide, octreotide and glucagon), and enteral and intravenous administration of glucose, according to the particular needs of each patient.

All patients underwent an 18fluoro-L-3-4 dihydroxyphenylalanine positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18-F-DOPA-PET/CT) using a low dose protocol for the CT. Scans were performed at our institution under an Investigational New Drug (IND) protocol reviewed by the Institutional Review Board, Radiation Safety Committee and the Food and Drug Administration. After injection of 18-F-DOPA, patients underwent a non-contrast CT followed by PET acquisition of 5 consecutive 10 min scans.

All surgeries were done through a transverse supraumbilical laparotomy. The pancreas was completely exposed by an extended Kocher maneuver, entry into the lesser sac, and mobilization of the inferior border of the pancreas. Biopsies were taken from the pancreatic head, body, and tail for intraoperative frozen section analysis. When a near-total pancreatectomy was performed, only a small residual piece of pancreatic tissue was left in place between the common bile duct and the duodenal wall. When a subtotal pancreatectomy was performed, the pancreas was resected from the tail to the neck (75% resection) or from the tail to the middle of the head (85% resection).

Genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array was used to search for uniparental disomy and loss of heterozygosity.

2. Results

Four patients with BWS and severe HI underwent pancreatectomy, 3 females and 1 male (Table 1). The age at the time of pancreatectomy was 1, 2, 4 and 12 months respectively. The median operative time for pancreatectomy with multiple frozen section biopsies was 189 min (range: 173–224). The diagnosis of BWS was established by the clinical features and/or by the presence of mosaic 11p15 loss of heterozygosity and uniparental paternal disomy (UPD) in peripheral blood and/or pancreatic tissue.

Table 1.

Patient summary.

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | M | F | F | F |

| Age at Surgery | 12 months | 4 months | 2 months | 1 month |

| Preoperative GIR | 3.5 mg/kg/min | 30 mg/kg/min | 25 mg/kg/min | 19 mg/kg/min |

| Preoperative PET/CT | Diffuse tracer uptake | Diffuse tracer uptake | Diffuse tracer uptake | Large area of increased uptake in the pancreatic body |

| Procedure | 75% Pancreatectomy | 90% Pancreatectomy | 95% Pancreatectomy | 85% Pancreatectomy |

| Genetics in pancreatic tissue | 11p15 paternal UPD in 85% of the pancreatic cells. | Whole chromosome 11 paternal UPD in 99% of pancreatic cells | Whole-genome paternal UPD in 90% of pancreatic cells | Whole chromosome 11 paternal UPD in 50% of pancreatic cells |

| Outcome | Fasted safely 5 days after surgery | Fasted safely 1 month after surgery | Fasted safely 1 year after surgery | Fasted safely 12 days after surgery |

| Other findings | – | Focus of pancreatoblastoma. Hepatoblastoma at age 2 | Multiple hepatic hemangiomas. | – |

GIR: glucose infusion rate; UPD: uniparental disomy.

All patients had profound hypoglycemia since birth. Medical management with diazoxide and octreotide did not provide improvement in any case. The patient operated at 1 month of age required an intravenous glucose infusion rate (GIR) of 19 mg/kg/min prior to the surgery to remain euglycemic. The patient operated on at 2 months of age required an intravenous GIR of 25 mg/kg/min prior to the surgery to maintain euglycemia. The patient operated on at 4 months of age had been on a combination of continuous enteral glucose infusion (D20) via gastrostomy at a rate of 12 mg/kg/min, and just prior to the operation required an intravenous GIR of 30 mg/kg/min to remain euglycemic. The patient operated on at 12 months of age had a milder clinical course but despite a strict regimen of frequent feedings, blood glucose levels dropped below 50 on a daily basis. Prior to the surgery he required a continuous intravenous GIR of 3.5 mg/kg/min.

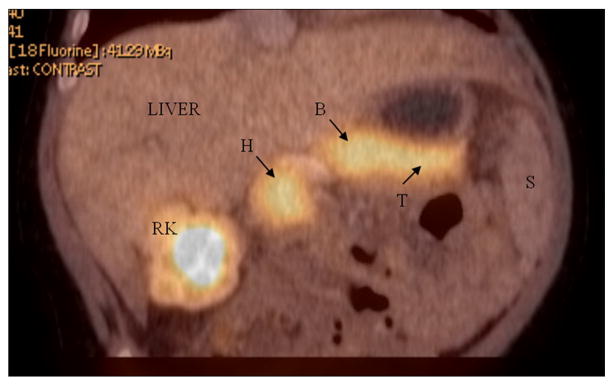

All patients underwent a preoperative 18-F-DOPA PET/CT to rule out the focal form of HI. The studies showed diffuse uptake of the radiotracer throughout an enlarged pancreas in three patients (Fig. 1) and a normal sized pancreas with a large area of focal uptake in the pancreatic body in one patient.

Fig. 1.

18-F-DOPA PET/CT scan showing diffuse homogeneous tracer uptake at the head (H), body (B) and tail (T) of the pancreas. S = spleen. RK = right kidney.

Genetic testing showed no mutations in the ABCC8 or KCNJ1 genes (which are typically associated with diazoxide-resistant congenital HI) in any of the patients. The patient operated on at 1 month of age had a non disease-causing intronic variant on the maternal copy of the ABCC8 gene, no loss of heterozygosity in peripheral blood white cells (PBWC), and mosaic whole chromosome 11 paternal UPD in 50% of pancreatic cells (both endocrine and exocrine). The patient operated on at 2 months of age had mosaic whole-genome paternal UPD in 85%–95% of PBWC and whole-genome paternal UPD in 90% of pancreatic cells. The patient operated on at 4 months of age had paternal UPD of the whole chromosome 11 in 80% of PBWC and in 99% of pancreatic cells. The patient operated on at 12 months of age had no detectable abnormalities in PBWC, but had 11p15 UPD in 85% of the pancreatic cells.

We tailored the extent of the pancreatectomy according to HI severity. The two patients that required the highest GIR (25 and 30 mg/kg/min) underwent a 95% and 90% pancreatectomy, respectively. The patient that required a somewhat lower GIR (19 mg/kg/min) underwent an 85% pancreatectomy. These patients had a markedly enlarged pancreas on imaging and diffuse 18-F-DOPA uptake. The patient with the milder clinical course (GIR 3.5 mg/kg/min) underwent a 75% pancreatectomy at 1 month of age and had normal histology of the pancreatic tail and marked endocrine hyperplasia in the head, neck and body. In this case the 18-F-DOPA revealed a large area of focal uptake in the pancreatic body.

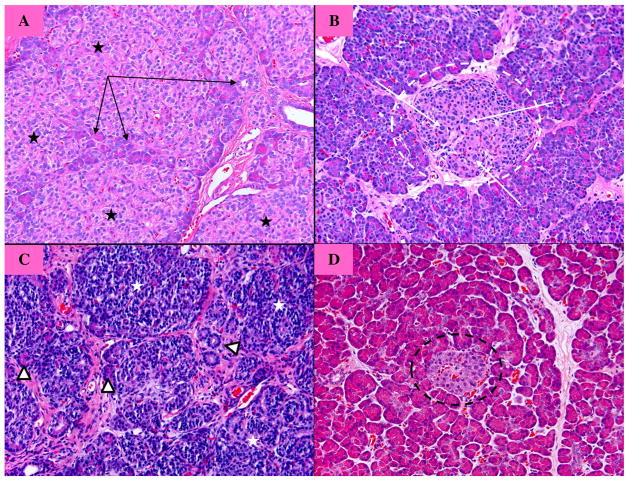

On histology, pathologic changes were variable among affected patients but in all cases were characterized by a remarkable increase in endocrine tissue relative to the amount of exocrine tissue, with variable degrees of loss of the normal lobular architecture of the pancreatic parenchyma (Fig. 2). The endocrine tissue occupied up to 80% of the parenchyma. In many cases, islets demonstrated a prominent trabecular arrangement of endocrine cells, with or without scattered individual islet cell nucleomegaly. The findings are in contrast to those seen in patients with congenital hyperinsulinism due to focal or diffuse lesions where the increase in endocrine tissue is localized to an affected portion of pancreas or is associated with isolated nucleomegaly in otherwise normal islets, respectively. In one patient the increased and architecturally complex endocrine tissue was concentrated within the head and body with tapering to near-normal morphology in the tail (this was consistent with the lower signal at the pancreatic tail on her PET scan).

Fig. 2.

Histology of the pancreas (hematoxylin and eosin). (A) Focal lesion of congenital hyperinsulinism (HI). There is hyperplasia of the endocrine cells (black stars), with a few acinar and ductal cells embedded within the lesion (black arrows). These features are exclusively confined to the focal lesion. (B) Diffuse form of congenital HI showing endocrine cells with nucleomegaly (white arrows), the most characteristic histological feature, within an otherwise normal islet of Langerhans (dotted white circle). (C) Beckwith–Wiedemann. There is a remarkable proliferation of endocrine cells (white stars) that occupy more than 80%–90% of the parenchyma. There are scattered cells of acinar and ductal origin (white triangles). The endocrine cells have very little cytoplasm and form rudimentary lobules. (D) Normal pancreatic histology: there is no islet cell nucleomegaly and the endocrine component (black dotted circle) represents a small portion of the parenchyma.

The HI improved in all cases after the pancreatectomy. The patient who underwent an 85% pancreatectomy was weaned off intravenous glucose infusion within 10 days, and fasted safely for 18 h at 12 days after the operation. The patient who underwent a 95% pancreatectomy was able to wean the rate of glucose intake over the course of several months and fasted safely for 10 h at 1 year of age. She is now 2 years old, takes oral feedings during the day, and receives a low enteral glucose infusion overnight via gastrostomy. The patient who underwent a 90% pancreatectomy weaned his glucose intake quickly and fasted safely for 9 h one month after the operation. At 3 1/2 years of age, he is exclusively on oral feedings. The patient who underwent a 75% pancreatectomy was able to fast safely for 18 h immediately after the operation and was discharged home exclusively on oral feedings. To date, no patient is diabetic or has evidence of pancreatic exocrine insufficiency.

One patient had a small focus of pancreatoblastoma in the pancreatectomy specimen. The same patient developed a hepatoblastoma at age 2. All patients are under surveillance for embryonal tumors according to the guidelines described by Teplick et al. [8].

During the analyzed period we cared for eight other BWS patients with HI which could be managed medically.

3. Discussion

The genetic basis of BWS is remarkably complex. Several genetic derangements can lead to the disease, but all of them have in common the abnormal expression of imprinted genes located in the p15.5 region of chromosome 11 that regulate cell proliferation. The majority of patients with BWS (≈ 55%) have a sporadic abnormal methylation of the centers that control the expression of those imprinted genes, leading to an imbalance towards cell proliferation. Twenty percent of patient with BWS have a sporadic somatic mosaic paternal uniparental disomy (UPD) involving at least the 11p15.5 region. The p15.5 region of the maternal chromosome is lost and replaced by a duplicate of the paternal region, which also results in an imbalance of gene expression towards cell proliferation. Two patients in our series had mosaic 11p15.5 UPD in peripheral blood and pancreatic tissue, and exhibited other clinical features of BWS. The other two patients had UPD in pancreatic tissue but not in peripheral blood (no other tissues were examined) and they did not have other somatic features of BWS. These patients may be at the mildest end of the clinical spectrum of BWS or may represent a forme fruste of the syndrome, where there is only one isolated clinical feature, and UPD is exclusively present in the affected tissue [2,9–11]. Fifteen percent of patients with BWS have an inherited genetic defect involving one or more imprinted genes of the 11p15.5 region. And finally, in approximately 10% of patients with BWS the genetic derangement is unknown. The genetic alterations that lead to BWS occur and manifest early in development, when the genes involved in tissue growth are expressed at their highest rate. When any of the genetic events described above occurs in a pancreatic progenitor islet cell, the result is an abnormal proliferation of endocrine cells, as seen in cases of focal congenital HI and some patients with BWS.

The etiology of the hypoglycemia observed in BWS patients is unknown. There is no known correlation between any particular genetic variant and the risk of hypoglycemia. Patients with BWS hypoglycemia have hyperinsulinism (as observed in our four patients) as defined by three criteria: serum concentration of insulin inappropriately high for the glucose level, inappropriate inhibition of lipolysis (low ketones in plasma and urine), and positive response to glucagon (which proves that the hypoglycemia is not due to exhausted hepatic glycogen deposits). The vast majority of patients respond to diazoxide (an inhibitor of insulin secretion), which also supports that BWS hypoglycemia is secondary to hyperinsulinism. Several mechanisms have been proposed for the hyperinsulinism in BWS. IGF2 is a weak agonist of the B isoform of the insulin receptor and is overexpressed in a variety of neoplasms causing severe hypoglycemia [12,13]. IGF2 is over-expressed in about 30% of patients with BWS, which could explain at least in part their hypoglycemia. For patients unresponsive to diazoxide it has been speculated that the hypoglycemia could be related to mutations in the genes associated with diazoxide-resistant congenital HI, namely ABCC8 and KCNJ11, which encode the K-ATP channel of the beta cells and are also located in the 11p15 region. None of our patients had disease-causing mutations in either gene, and to date there has been no such case reported in the literature. There has been a single case report of a patient with UPD-BWS and hypoglycemia who had a defect in the function of the K-ATP channel of the beta cells, but with no mutations in either gene [14].

Despite the unclear pathophysiology of BWS hyperinsulinism, patients with severe hypoglycemia unresponsive to medical treatment should be considered for a partial or near-total pancreatectomy. No guidelines exist regarding the percentage of the pancreas that needs to be removed in order to control the hypoglycemia. Very few cases have been reported in the literature (Table 2). Little can be extrapolated from the surgical management of patients with congenital HI because BWS-related hypoglycemia is clinically heterogeneous and histologically different than all the variants of congenital HI (diffuse, focal and atypical). Our surgical approach has been to do a near-total pancreatectomy in patients with severe disease, and a partial pancreatectomy if the clinical course was milder. The hyperinsulinism in BWS tends to improve with time, with and without surgery, even in those cases that are severe and prolonged. This is an argument against performing a near-total pancreatectomy in BWS patients with severe hypoglycemia. In our opinion, the risk of profound brain damage that can occur as a result of recurrent severe hypoglycemia demands a pancreatic resection, even in light of the potential risk of pancreatic endocrine and exocrine insufficiency. Similar to what occurs in patients with diffuse congenital HI, the near-total pancreatectomy in patients with severe hyperinsulinism and extremely high GIR requirements is not a cure but a palliative treatment that makes the disease more easily manageable, as seen in our 2 patients who underwent 95% and 90% pancreatectomy. In patients with a milder clinical course, a partial pancreatectomy seems to be a reasonable approach because it hastens the progression of the disease towards a remission (as seen in our patients who underwent 85% and 75% pancreatectomy, virtually cured a few days after the operation), without the potential risk of pancreatic insufficiency. We have no data to support that the resection of a smaller portion of the pancreas would not have resulted in the same outcome. During the analyzed period we treated another patient with mild diazoxide-resistant BWS hyperinsulinism. The parents did not agree to a pancreatectomy; biopsies were done for diagnostic purposes at the age of 10 months. The patient had paternal 11p15.5 UPD in 85% of pancreatic cells. He required the same continuous GIR after the biopsies, as expected, but over the course of the following 2 years his hyperinsulinism improved spontaneously and he is currently on a regimen of overnight continuous feeds and bolus feeds during the day. This case illustrates that in patients with a mild clinical course the indication for a pancreatectomy is not as strong as in patients with severe disease, and continuing supportive therapy as a bridge towards spontaneous remission should be considered a feasible option. In addition, BWS patients with hyperinsulinism that responds appropriately to diazoxide should not undergo pancreatectomy. The utility of 18-F-DOPA PET/CT is unclear in cases requiring surgery, but it may be a helpful additional tool to decrease the amount of pancreas resected if a focal area of increased radiotracer activity is detected.

Table 2.

Previously reported cases of pancreatectomy in patients with Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome.

| Author | Roe [15] | Meissner [16] | Hussain [14] | Flanagan [10] a | Our study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1973 | 2001 | 2005 | 2011 | 2013 |

| # of patients | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Age at surgery | 24 days | N/A | N/A | 9 weeks/7 weeks | 1 m/2 m/4 m/12 m |

| Procedure | 80% pancreatectomy | 87.5% pancreatectomy | Near-total pancreatectomy | Near-total pancreatectomy | 95%/90%/85%/75% pancreatectomy |

| Genetics | N/A | 11.15.5 pUPD | 11.15.5 pUPD | 11.15.5 pUPD | See results section |

| Outcome | Relatively fast improvement. Euglycemia with frequent feeds only at 2 months of age | Improvement. No detailed data available | Slow improvement. Euglycemia with feeds only at 14 months of age. | Fast improvement in case 1. Slow improvement in case 2 (on Diazoxide at 6 years of age). | See results section. |

| Histology | Marked endocrine hyperplasia. | N/A | Marked endocrine hyperplasia. | Marked endocrine hyperplasia. | Marked endocrine hyperplasia. |

| Postoperative pancreatic insufficiency | N/A | N/A | N/A | Exocrine insufficiency in 1 patient | No |

N/A = No data available. pUPD = paternal uniparental disomy.

= These two patients had pUPD in the pancreas, no abnormality of the ABCC8 or KCNJ11 genes, and no other clinical features of BWS.

In summary, the pathophysiology of BWS hyperinsulinism is not yet well understood, but it is likely that multiple factors are involved. The pancreases of patients with BWS hyperinsulinism exhibit a remarkable hyperplasia of endocrine cells. Reducing the mass of endocrine tissue by means of a pancreatectomy is a therapeutic option for patients with medically unresponsive severe hypoglycemia.

References

- 1.Weksberg R, Shuman C, Beckwith JB. Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:8–14. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choufani S, Shuman C, Weksberg R. Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2010;154C(3):343–54. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beckwith JB. Extreme cytomegaly of the adrenal fetal cortex, omphalocele, hyperplasia of kidneys and pancreas, and Leydig-cell hyperplasia: another syndrome?. Presented at the 11th annual meeting of the Western Society for Pediatric Research; Los Angeles, CA. November 11; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiedemann HR. Complexe malformatif familial avec hernie ombilicale et macroglossie, un syndrome nouveau. J Genet Hum. 1964;13:223–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckwith JB. Vignettes from the history of overgrowth and related syndromes. Am J Med Genet. 1998;79:238–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott M, Bayly R, Cole T, et al. Clinical features and natural history of Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome: presentation of 74 new cases. Clin Genet. 1994;46:168–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1994.tb04219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeBaun MR, King AA, White N. Hypoglycemia in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Semin Perinatol. 2000;24:164–71. doi: 10.1053/sp.2000.6366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teplick A, Kowalski M, Biegel JA, et al. Educational paper: screening in cancer predisposition syndromes: guidelines for the general pediatrician. Eur J Pediatr. 2011;170:285–94. doi: 10.1007/s00431-010-1377-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weksberg R, Shuman C, Smith AC. Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2005;137C(1):12–23. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flanagan SE, Kapoor RR, Smith VV, et al. Paternal uniparental isodisomy of chromosome 11p15. 5 within the pancreas causes isolated hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2011;2:66. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2011.00066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanley CA, De Leon DD. Monogenic hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia disorders; frontiers in diabetes. Vol. 21. Basel Switzerland: Karger AG; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korevaar TI, Ragazzoni F, Weaver A, et al. IGF2-induced hypoglycemia unresponsive to everolimus. QJM. 2011:104. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr249. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan G, Horton PJ, Thyssen S, et al. Malignant transformation of a solitary fibrous tumor of the liver and intractable hypoglycemia. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:595–9. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussain K, Cosgrove KE, Shepherd RM, et al. Hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia in Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome due to defects in the function of pancreatic beta-cell adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:4376–82. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roe TF, Kershnar AK, Weitzman JJ, et al. Beckwith’s syndrome with extreme organ hyperplasia. Pediatrics. 1973;52:372–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meissner T, Rabl W, Mohnike K, et al. Hyperinsulinism in syndromal disorders. Acta Paediatr. 2001;90:856–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]