Abstract

The need to ensure the future pharmacy workforce demonstrates professionalism has become important to both pharmacy educators and professional bodies.

Objective

To determine the extent to which Schools of Pharmacy have taught or measured student professionalism.

Methods

Review of the healthcare literature on teaching of professionalism at an undergraduate level

Results

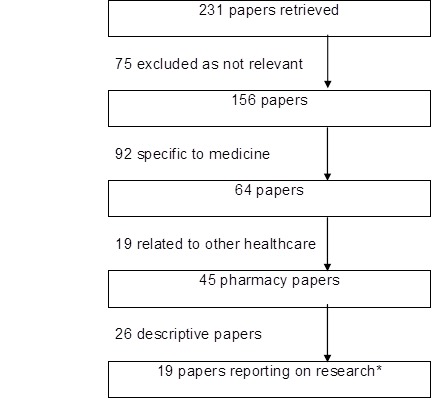

Two-hundred and thirty one papers were retrieved but only 45 papers related specifically to pharmacy. Of these a further 25 were narrative in nature and did not report any findings. Nineteen papers were reviewed (one was excluded as it reported the same data). Papers could be broadly categorised in to those that have tried to create a tool to measure professionalism, those that are in effect pedagogical evaluations of new initiatives or longitudinal studies on student perceptions toward aspects of professionalism.

Conclusion

A growing body of literature exists on pharmacy and professionalism. However, to date, very few Schools of Pharmacy appear to formally teach it let alone assess students’ acquisition of professionalism.

Keywords: Education, Professional, Students, Pharmacy

INTRODUCTION

The occupations of law, theology and medicine have been traditionally recognised as being ‘true’ professions.1 However, over time many more occupations have aspired to professional status, including pharmacy. Much debate has taken place over what constitutes a profession, a professional and the concept of professionalism.2-9 Attacks by sociological theorists in the 1960s and 1970s challenged occupations with professional status and the monopoly they hold over society.10-11 Pharmacy was not immune to this, with the profession being labeled a quasi profession, in as much it had some but not all characteristics of a profession.4

Subsequently, the pharmacy literature saw many commentators discussing the profession in terms of becoming ‘deprofessionalised’ or the need for it to ‘reprofessionalise’ to maintain its professional status.12-13 At this time the first research in pharmacy was being conducted to determine the concept of professional socialisation at an undergraduate level.14-18 Pharmacy though was not alone in the process of navel gazing; medicine had been particularly targeted by sociologists and they too were grappling with how best to ensure that doctors of the future possessed the necessary attributes required to continue to be held in esteem by society. This culminated in medical organizations in the US and Europe collaborating on the medical professionalism project, which sought to establish a set of principles that included 6 tenets of professionalism.19 This was followed in 1998 with recommendations for professionalism to be included in core curriculum and then in 2002 instruction on how this could be assessed.20-21 Pharmacy organizations in the US also considered this approach and in 2000 a joint APhA-ASP/AACP-COD white paper on pharmacy student professionalism was published22; further publications followed, including a pharmacy professionalsim toolkit for students and faculty.23-24 These publications gave US schools of pharmacy a ‘blueprint’ in which to tackle the teaching and assessment of professional traits at an undergraduate level. This paper examines what progress has been made in relation to the teaching and assessment of professionalism within undergraduate curricula.

METHODS

Papers were initially identified via searches on electronic databases that included EMBASE, MEDLINE, CINAL, PsycINFO, Australian Education Index, British Education Index and International Pharmaceutical Abstracts. No limits were set on when the papers were published. A range of search terms were used that combined various derivations of the word profession, medicine and pharmacy and limited to the fields of title or abstract. In addition, reference lists from those articles identified as relevant were searched and any papers deemed appropriate were also reviewed.

Only papers that involved some element of teaching or assessment in an undergraduate context were included. Papers excluded were those of non-English language; papers that were predominantly descriptive in nature and did not report on any research findings; and, personal or professional body opinion. Papers were reviewed and data extracted independently by the first author and two research assistants before being data entered in to Excel.

RESULTS

A total of 231 papers were retrieved. However, not all met the defined inclusion criteria as depicted in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Selection of Papers for Review.

* Two papers reporting the same study, thus only 1 included for analysis

The eighteen papers identified were reviewed by the authors, and details of each paper are shown in Annex 1.

Annex 1.

Details of Reviewed Papers

| Reference | Aim/objective | Methodology | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berger BA, Butler SL, Duncan-Hewitt W, Felkey BG, Taylor C, et al. Changing the culture: An institution-wide approach to instilling professional values. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1):22 | To introduce organizational change based on the recommendations from the White Paper Student Professionalism | Outlined the key steps introduced to their School of Pharmacy (SoP):1. Appointment of recruiter to actively promote SoP to pre-university students; 2. Revised recruitment process that centered on interview placing greater emphasis on items such as caring and citizenship and additionally given a test on ‘cognitive moral development’; 3. Orientation process introduced for students (and new staff). Students given 5 day program culminating in ‘white coat ceremony’ - some sessions involved students parents and specific sessions on professional socialization process; 4. Introduction of a practice experience program where students assigned patients where they spend time each week with the patient and report back to staff about their experiences; 5. ‘Early concern notes’ being considered for introduction to program that flag up deficiencies in professional behavior and could stop progression regardless of academic performance. | Applications increased post appointment of ‘recruiter’ from 225 in 2002 to 425 in 2003. Students academic scores also increased rising from a grade point average of 3.30 to 3.41 and degree entrants rose from 19 to 45% of the cohort. A number of students (not specified) were rejected on interview alone despite high grade point average. Staff feed back on orientation process was positive (used 5 point Likert scales, strongly agree to strongly disagree). Student feedback very positive toward the practice experience program (5 point Likert scales as above) and 79% stated that career aspirations had changed as a result of the orientation program but only 27% said they had learnt what it is to be a professional. |

| Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Morgan JA, de Bittner MR. Professionalism: A determining factor in experiential learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2):31 | Subsequent to the White Paper on Student Professionalism this School of Pharmacy (SoP) had introduced some organizational changes and paper reports on how they have attempted to measure professionalism competency whilst student on experiential placements | Experiential program consisted of 16 rotations over 4 years ranging from 1 day visits to 12 week placements. Students previously assessed on professional behavior (pre 2001) based on 5 point Likert scales for punctuality, active participation, appropriate interaction and attire. Deemed unreliable and low ratings did not stop progression. Faculty developed new criteria of three professional behaviors; patient and provider communications, appearance and attire and timeliness and commitment. Students had to be rated in all 3 areas as outstanding or competent to pass the rotation | From the 167 students attending ‘intermediate’ rotations only 1 student failed on these behavioral elements - the student subsequently repeated the course and passed. Those attending ‘advanced’ rotations (n=371) again only 1 student failed resulting in academic suspension. The criteria were refined in 2004 and rating scales changed to acceptable/unacceptable. Since its inception in 2001 just 9 students have failed. Preceptor opinion was sought and a consistent message was that preceptors were reluctant to fail students based on one instance of poor behavior but were they to see repeated poor behavior then they would have submitted an ‘unacceptable’ rating. |

| Brehm B, Breen P, Brown B, Long L, Smith R, Wall A, et al. An interdisciplinary approach to introducing professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4):81. | To use an inter disciplinary approach to introduce students to the concept of professionalism using structured activities in an academic and clinical setting | Approach involved the faculty of nursing, pharmacy and allied health sciences (involving 8 health care disciplines). Students given a half day orientation session on the importance of professionalism in clinical sites prior to the start of the academic year. Consisted of lectures, role play and case studies. In addition, student groups were mixed and asked to discuss what constitutes professionalism and listing the 5 most important characteristics. The 10 commonest characteristics from all groups were subsequently used during evaluation (incorporated in to a survey consisting of 5 point Likert scale statements using strongly agree to strongly disagree). Subsequent to orientation students (in their interdisciplinary groups) visited a clinical site to observe practice and the roles of different health professionals. | Students were asked to complete a survey on the orientation program and their experience at the clinical sites. For the orientation program 284/342 (88%) of students completed the survey. Almost all (95%) agreed professionalism was an important discussion topic prior to attending placements and the majority of students felt that orientation increased their awareness of professionalism and agreed the orientation process would enhance their future interactions with other health disciplines. 123/163 (75%) responded to the survey regarding the site visit. This too used Likert scales (4 point, where 1 represented not at all and 4 a great deal). Student views showed that they felt they benefited from the visit, the experience made them more aware of the potential opportunities available and the presence of their profession would improve patient care. |

| Bumgarner GW, Spies AR, Asbill CS, Prince VT. Using the humanities to strengthen the concept of professionalism among first-professional year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2):28. | To make students early in their course more aware of professionalism and to stregthen the ‘calling to serve’. | A booklet was devised that contained 4 short stories. This was mailed to students entering their first professional year of their PharmD program as ‘summer reading’. This was then to be discussed with students during orientation. Stories were selected as they applied to pharmacy and encompassed elements of professionalism. Students were divided in to groups of 8 to 10 and met for 90 minutes with a faulty facilitator to discuss the stories. Initiative evaluated by survey using 5 point Likert scale (strongly agree to disagree) but administered to all students | Findings reported on the first 2 cohorts to experience the initiative. 111/123 (90%) and 107/122 (87%) completed the survey. Students mean scores for both cohorts were high and suggested they were engaged in the discussion on professionalism. When the survey was administered to those students who had not participated scores were similar (significance not reported), although authors state there was an upward trend in items that reflected sense of personal mission and calling to serve. |

| Chisholm MA, Cobb H, Duke L, McDuffie C, Kennedy WK. Development of an instrument to measure professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4):85. | To both develop and validate a survey to measure professionalism on undergraduate and recent pharmacy graduates | Focus group used to develop survey items but based around the American Board of Internal Medicines 6 tenets of professionalism (excellence, respect for others, altruism, duty, accountability, honor/integrity) to provide developmental direction. 51 items produced which was then reduced to 32 after pre-testing. Survey items utilized a 5 point Likert scale of strongly agree to strongly disagree. | 130/133 (98%) of year 1 pharmacy students and 101/124 (81%) recent graduates completed the survey. Post descriptive analysis 8 items were removed due to lack of discrimination and a further 4 omitted due to lack of understanding indicated by participants, and finally a further 2 were deleted by the authors. This left 18 items that could be used for factor analysis. Paper went on to report more on the development and validity of the survey rather than the results obtained form participants. However, it did report no difference in opinion between first year and new graduate pharmacy students. |

| Duke LJ, Kennedy K, McDuffie CH, Miller MS, Chisholm MA, et al. Student attitudes, values, and beliefs regarding professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69(5):104 | To determine if students shared SoP objectives on competency on professionalism | Survey sent via intranet to 240 (60 from each year) randomly selected students. Students rated 2 series of statements (both 5 point Likert scales, using strongly agree to strongly disagree). Series I incorporated 34 items and series 2 had 8 items. Series 1 were aligned to the SoP objectives on professionalism competency and series 2 asked students to assess the level of professionalism exhibited within the faculty. | 177/240 (74%) returned the survey after 1 reminder. Agreement levels toward curricular professionalism objectives were high (range 79 - 100%) and were similar across cohorts with only 4 statements showing statistically differences across cohorts. With respect to professionalism within the SoP some differences between cohorts were seen and in general agreement to statements declined in the first three years only to rebound in the fourth year (although not significant) |

| Fung SM, Norton LL, Ferrill MJ, Supernaw RB. Promoting professionalism through mentoring via the internet. Am J Pharm Educ. 1997;61:166-9. | Introduction of a mentoring program to first year pharmacy students to encourage early professionalism | Year 1 pharmacy students (approx. 200) assigned a pharmacist mentor. Mentor could be from a wide geographic area so communication route via email. Surveys sent to students, mentors and staff of SoP to evaluate the initiative. | 99 students and 89 mentors replied to the survey. Mentors (97%) and students (71%) found the interactions enjoyable and rewarding. All mentors recommended continuation of the program in contrast to 57% of students. Almost all mentors (96%) were prepared to participate in future years. 40% of students felt it was too time consuming compared to just 5% of mentors. Students did though (65%) feel the mentor provided a better picture of the profession and 61% stated it added value to their education. It is unknown from the results whether the objective of encouraging professionalism was achieved. |

| Hammer DP, Mason HL, Chalmers RK, Popovich NG, Rupp MT. Development and Testing of an Instrument to Assess Behavioral Professionalism of Pharmacy Students. Am J Pharm Educ 2000;64:141-51. | As title of paper | Literature review identified various student evaluation forms from both pharmacy and medicine. 38 professional behavior items identified representing seven dimensions; standards, responsibility, competence, maturity, initiative, appearance and interpersonal relations/communication skills. Peer review by 90 experiential program co-ordinators and preceptors resulted in 37 reworded items. 5 point Likert scale was (1 = unsatisfactory and 5 = excellent). | Piloted on 312 students and preceptors. 121 student and 132 preceptor responses. Paper then goes on to report principally on exploratory factor analysis prior to large scale administration. Resulting analysis reduced items from 37 to 25 representing four dimensions; responsibility; interpersonal/social skills; communication skills and appearance. When survey repeated on 994 students, factor analysis confirmed original findings. |

| Hatoum HT, Smith MC. Identifying patterns of professional socialisation for pharmacists during pharmacy schooling and after one year in practice. Am J Pharm Educ 1987;51: 7-17. | Attempt to see what effect the professional socialization process has on students over time | A survey was developed utlizing previous scales and adapted for this study. The scale sought to evaluate some components of the professional role and were categorized into a) people, b) status, and c) science. The authors attempted to validate these revised scales. The survey was given to all students at the beginning of the academic year between 1978 and 1980 and to all new practitioners that graduated in 1979. No data is reported on response rates. | A mixed picture between years and the different scales was observed. Broadly speaking students showed orientation to the ‘people’ and ‘’science’ components. However, if the subscale of professionalism was included in the analysis then orientation toward these components decreased. The results of the professionalism subscale showed low scores for new students and qualified practitioners. |

| Knapp DE, Knapp DA. Disillusionment in pharmacy students. Soc Sci Med. 1968;1:445-47. | to describe the nature of any disillusionment pharmacy students experience | Students from sophomore, junior and senior classes were asked to complete a series of 19 variables using a 7 point scale regarding their opinion on 4 occupations (pharmacist, technician, ‘professional’ and physician | Findings showed that seniors had more negative perceptions than junior and sophomore students both toward pharmacists and the other three groups listed. |

| Lerkiatbundit S. Professionalism in Thai pharmacy students. Journal of Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2000;17(1):51-8. | describe and explain professionalism in pharmacy students | Survey developed (see Lerkiabundit 2005) and given twice to all students on the course. Firstly within 2 weeks of the academic year and then in the last 2 weeks of the academic year. Only those surveys completed on both occasions were included for analysis. | Results showed an increasing trend of the beliefs in professional organization and public services for all years except freshmen. In addition freshman were found to have a decrease in professional commitment but an increase in autonomy and self-regulation compared to upperclassmen |

| Lerkiatbundit S. Factor structure and cross-validation of a professionalism scale in pharmacy students. Journal of Pharmacy Teaching. 2005;12(2):25-49. | To investigate factor structures of an attitudinal professionalism scale | Scale revised from scale developed by Schack-Hepler scale which covered 6 dimensions of professionalism; professional organization; continuing education; autonomy; public service; self-regulation and professional commitment. Survey distributed to all students in classes from 1999-2003 and follow up surveys conducted at different time periods of students’ studies. | Results concentrate totally on the factorial validity of the survey. Reported that six subscales of the survey were reliable (Cronbach alpha > 0.7). A six factor correlated model was better than other models, e.g. as opposed to uncorrelated and one factor models. |

| Paik C, Broedel-Zaugg K. Pharmacy students’ opinions on civility and preferences regarding professors. Am J Pharm Educ 2006;70(4):88 | To determine undergraduate opinion on classroom behavior and preference toward academic staff | SoP working on the premise that students expected to present a professional demeanor in the classroom setting as a first step in becoming a pharmacy professional and that civility must be present to have professionalism. Therefore a survey designed to determine what pharmacy students perceive as uncivil behavior. Survey split in to 3 sections. Section 1 to determine their opinion (30 items using 5 point Likert scale of strongly agree to strongly disagree); section 2 preference for contacting staff (18 items, scale as previous) and section 3 to gain demographic data. Survey sent to first year of profession of pharmacy course (freshman year) and repeated 2 and 3 years later to same cohort | First survey (254/277, 92%); second survey (174/190, 92%); third survey (160/180, 89%). However, those used in analysis were 136, 129 and 130 respectively from each cohort. Making offensive remarks, prolonged chatting, cheating and use of mobile phones/bleeps were seen as most uncivil in each of the surveys (score of >4.0, where a score of 1 = low incivility and 5 = high incivility)> Of greatest importance to students regarding staff was that lecturers care about their learning experience. |

| Schwirian PM. Professional Socialization and Disillusionment: The Case of Pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 1974:18-23. | To determine changes in student attitude toward the profession as progress through the undergraduate course and compare to staff opinion | 3 surveys given students and staff over a 3 year period from 24 SoPs. Survey 1 (1970/71) to students; survey 2 (1971/72) to staff and survey 3 (1972/73) follow up survey to students. Eleven statements on attitudes toward pharmacy the same for student and staff. | Only matched surveys analyzed for students (n=653) and 317 staff replies. Students revealed more negative attitudes toward pharmacy after 2 years of study. Values were higher (i.e. less negative) than staff attitudes but had moved in the direction of staff scores. No evidence to substantiate that staff caused this shift in opinion. |

| Shuval JT. Attempts at Professionalization of Pharmacy: An Israel Case Study. Soc Sci Med. 1978;12:19-25. | Discusses attempts made by pharmacy students to develop coping mechanisms during professional socialization. | Data collected from students over 4 time points: before entry; end of year 2; end of year 4; and, receipt of degree. Students asked opinion on 8 statements (Likert scales) relating to potential rewards ranging from income to job satisfaction. | As students progress through the course a drop in expectation was observed for the rewards that future practice holds. |

| Smith M, Messer S, Fincham JE. A Longitudinal Study of Attitude Change in Pharmacy Students During School and Post Graduation. Am J Pharm Educ. 1991;55:30-5. | To investigate changes that occur on selected attitudes of pharmacy students during undergraduate education and post qualification | Reports on data from 1981 to 1985. Survey (Likert-type questions) issued at 4 time points; start of year 1;start of year 2; mid-way through final year; and, one year after graduation. Survey consisted of demographic data and three validated scales developed by other authors. | Results suggested significant decreases in professional identity over time and an increase in community health orientation during undergraduate study but following graduation fell. |

| Sylvia LM. Enhancing professionalism of pharmacy students: Results of a national survey. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(4):104. | To identify how far SoPs have implemented the White Paper on Student Professionalism | 83 SoPs surveyed using a 62 item survey that covered the 4 phases of a SoPs professionalism development plan: recruitment; admission; education program; and, practice | 52/83 (63%) response rate. Over 90% of SoPs used the white coat ceremony, oath of the pharmacist and student involvement in professional organizations. However, less than 50% used formal mentoring, maintenance of a portfolio, offered a sole course on professional development or provide scholarships in recognition of professionalism. |

| Yang TS, Fjortoft N. Developing into a professional: Students’ perspectives. Am J Pharm Educ. 1997;61:83S. | To determine from the student perspective how they learnt to be a professional | 20 students approached for interview (9 accepted); all transcribed and analyzed for themes | ethical development influenced by family (n=7); professional commitment related to rotations (n=6) as did professional identity and autonomy; |

Authorship

Fifteen of the eighteen papers originated from the US. The remaining three papers were from Israel15 and Thailand (same author).25-26 Seven papers were published prior to the APhA-ASP/AACP-COD paper on student professionalism.14-18,27,28 The remaining eleven papers were published post the white paper,25-26,29-37 with most seemingly using this, and subsequent position papers, as a catalyst for their work. 29-30,32-37

Student Perceptions

Seven papers focused on varying aspects of student opinion.14-18,28,36 All but the study by Paik et al36 were conducted prior to the 2000 white paper on student professionalism22, with five of these papers looking at student opinion as they progressed through the course.14-18 General findings from these papers show more negative attitudes; Schwirian et al15 and Smith16 both found students had a decrease in professional identity, and Shuval14 saw students’ expectations become lower as they progressed through the course. Knapp et al17 also found that students in the latter part of the course held more negative views toward their chosen occupation than those at the start of the course. Only the study by Hatoum et al18 described any positive findings portrayed by students as they progressed through the couse, however, these findings were not consistent between years or across the different variables measures and indeed scores from one particular subscale on professionalism saw students from all years attain low scores.

PaIk et al also conducted a longitudinal study, but unlike the previous studies that looked at general attitudes of students toward pharmacy, this study concentrated on just one behavioral trait of professionalism, civility.36 Student opinion remained relatively unchanged through the course with offensive remarks, prolonged chatting, cheating and use of mobile phones/bleeps being classed as the most uncivil behaviors. The final study by Yang was retrospective in nature and asked about how professional values were attained28; faculty faired poorly compared to clinical experience and influence of the family, and called in to question the undergraduate faculty experience.

Promotion of Professionalism

Various attempts have been made to introduce the concept of professionalism to undergraduate students. Berger et al29 report on re-engineering their program to not only recruit more able and committed students, but to instil a greater sense of what it is to be a pharmacist from the very beginning. Feedback from students was positive, although only just over a quarter stated that they had learnt about what it meant to be a professional. This theme of imprinting professional identity from the outset of study was also explored by Fung et al who provided students with a practitioner mentor.27 Findings however appear to show that students were less receptive to the mentorship scheme than the mentors themselves. Bumgarner et al32 took a different approach using literature to highlight professionalism. This study had a comparator group and the authors suggest that those enrolled in book reading did show greater tendency to a sense of personal mission and calling to serve. The study by Brehm et al31 allowed students from different health backgrounds to explore and define professionalism in the classroom before attending experiential placements. Students felt the orientation program had increased their awareness of professionalism with almost all believing it to be important.

Measuring Professionalism

No study before 2000 had attempted to measure professionalism, and of the papers subsequently written many reported on evaluation of their initiative and did not assess professionalism.29,31,32,34,36 Three authors have however constructed a survey tool to measure professionalism.25,26,33,35 All authors made attempts to create a reliable and valid survey tool. Lerkiabundit26 revised a previous scale, whereas Hammer et al developed their tool from an amalgamation of student evaluation forms.35 Chisholm et al took a different approach conducting focus groups to define survey items but using the American Board of Internal Medicines’ six tenets of professionalism as a reference point.33 All three papers report extensively on refining the survey tool to improve reliability and validity. Both Lerkiabundit and Chisholm et al also report on the findings observed within the student population as regard to measuring professionalism.25,33 Both studies looked at if student perception toward professionalism changed over time; Chisholm et al found no differences between new and graduated students and Lerkiabundit noticed differences between year groups, especially those in the freshman year.

In addition to survey tools that assess professionalism globally, Boyle et al introduced a measure of professionalism whilst students were on experiential placements.30 The study reports on a process of refining professional rating scales that can be used to independently pass or fail a student irrespective of academic performance. The system has shown that a small minority of students does fail solely on their professionalism ratings but the authors acknowledge that preceptors are inclined to give the student the benefit of the doubt.

Benchmarking

Two studies have looked at faculty progress in relation to student agreement with faculty competency statements34 and implementation of student professionalism white paper recommendations.37 The study by Duke et al found that students were in agreement with the competency statements devised by faculty and Sylvia found that nearly all responding faculties had implemented some (eg white coat ceremonies) but not all (e.g. mentoring schemes) recommendations.

DISCUSSION

During the literature review it quickly became evident that the topic of professionalism was widely discussed and debated both in medical and pharmacy circles. It appears that interest in the subject was triggered by the erosion (actual or perceived) of medicine’s professional status within the US, which made other professions re-examine their status. This is reflected in the body of literature that has been written on the subject. Most medical papers from the nineties and early part of the next decade emanate from the US, although over the last ten years a growing number of professional reports and research papers have been of UK origin.38-40 This in contrast to pharmacy where papers, including commentary-type papers, (only 1 of the 25 descriptive papers listed was from the UK) are almost exclusively from the US. The lack of peer-reviewed papers from outside the US is intriguing given that other Western countries such as the UK, Australia and New Zealand have similar undergraduate programs and broadly similar practising roles. Differences in legal frameworks, healthcare systems and structures and social identity may partially explain the lack of research in this area outside the US. Perception of pharmacists and their roles by the wider community in different settings may be a driver for such discourse, based on a perceived need. In the UK and Australia where there is little of this discourse, polls are conducted regularly by media and other agencies to evaluate public trust in a wide range of professionals. Pharmacy constantly ranks in first or second place in both countries as the professional in the community that people trust most.41,42 The result of this may be a perceived acceptable level of professionalism implying that educational and other processes are adequate for student preparation for professional life. One concern is that this allows for educators and regulators to “rest on their laurels” in these settings risking complacency and confusing public perceptions of a profession as a whole with attitudes and behaviors of individual members. It may be this lack of measured perception of the profession in the USA that has led to wider discussion and more structured recommendations there. A second concern about such “de facto” measures of professionalism is that the outcomes reflect on the profession as a whole and provide no indication of student capacity to “be professional” at the point of registration. Inevitably some newly qualified pharmacists will provide the basis of pharmacy professional experience for some survey respondents and their attitudes and behaviors will inform perceptions but it is not possible to determine if this trust is a reflection on undergraduate learning or observation and behavior modelling once in a professional practice setting.

However, traits associated with professionalism, such as student conduct and fitness to practice, are now being incorporated in to pharmacy schools in the UK at the behest of the UK professional body.43 In addition, in various jurisdictions of Australia, pharmacy students are required to register with the regulatory authority as early as their second year of undergraduate study.44,45 The reasons for this increase in regulator intervention is not clear but does point to growing acceptance, on the regulators behalf, that aspects of professionalism in the UK and Australia is not all it could be.

The majority of pharmacy literature centers on talking about professionalism rather than measuring students attainment of professionalism. This is understandable given that there has still yet to be a definitive definition of professionalism as it relates to the pharmacy profession which has been universally endorsed. Many commentators have put definitions forward and attempted to unpack the differing elements of what constitutes professionalism7, yet this lack of consensus is exemplified by the most recent American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) white paper on again defining what student professionalism constitutes.46 Even in those papers that have reported findings (Annex 1), all shy away from truly trying to determine whether attempts by faculty to teach and/or measure professionalism have succeeded. Boyle et al is the only paper which uses certain traits of professionalism (e.g. appearance, commitment, attire) as a means to stop academic progression.30 However, the traits singled out are a best a proxy measure in determining if someone is acting professionally. Survey tools have been developed to try and measure some if not all dimensions of professionalism but they do not appear to have been widely adopted and tested on student populations other than those in which the tools were developed.25,26,33,35 Therefore, for these tools to have credibility they need to be more widely used. A further development in determining professionalism has recently been put forward by Brown et al.47 The authors propose a taxonomic model involving three domains of professionalism where the emphasis is on performance and not learning. This, as of yet, untested model may provide faculties with a way forward for future measurement and assessment of professionalism.

Work has been conducted on gauging student opinion over time. Unfortunately, the majority of these are old and lack currency. It may be worth repeating these longitudinal studies again especially as most US faculties have now incorporated many of the 2000 white paper recommendations. Perhaps the negative attitudes of pharmacy students would be different given changes to the pharmacists’ role since those early studies and the greater emphasis placed on professionalism. However, there is a danger that qualifying students may become disillusioned in the legitimacy of their own profession when the “ivory tower” representation of what they will doing as pharmacists does not match with the reality of technical responsibilities of many pharmacists in practice. Hence, one of the challenges of professionalizing pharmacy students is to make them aware of this possible disparity as their education is equipping them for present and future roles, the latter which may not yet be widely practised.

It is certainly evident from these studies and other commentators that professional socialisation was, and continues to be, important in imparting the attributes of a practising pharmacist.2,28,48,49

CONCLUSIONS

Professionalism is a complex composite of structural, attitudinal and behavioural attributes and is therefore clearly difficult to measure, and is reflected in the lack of studies that have attempted to do so. However, if educators are to progress beyond reliance on role models or inculcation then a universally agreed definition of professionalism would be beneficial. From which teaching and learning strategies can be devised that incorporate appropriate assessment tools. The experiences from the US literature serve as a useful platform from which to move forward in a co-ordinated way.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with the submitted manuscript.

The work received no financial support from any granting body or outside organization.

Contributor Information

Paul M. Rutter, Department of Pharmacy, School of Applied Sciences. University of Wolverhampton. Wolverhampton (United Kingdom)

Gregory Duncan, Senior Health Services Research Fellow. Eastern Clinical School, Faculty of Medcine, Nursing and Health Sciences. Monash University. Melbourne (Australia).

References

- 1.Phillips A. Are the liberal professional dead, and if so, does it matter? Clim Med. 2004;4:7–9. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.4-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hammer P. Professional attitudes and behaviors: the “A's and B's” of professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64(4):455–464. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joyce MC. What Does Professionalism Really Mean. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2002;42(5):677–678. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montague JB. Pharmacy and the concept of professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1968;NS8(5):228–230. doi: 10.1016/s0003-0465(16)30606-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierpaoili MS. What is a professional? Hospital Pharmacy Times. 1992 May;:9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Toole PT, Kathuria N, Mishra M, Schukart D. Teaching professionalism within a community context: perspectives from a national demonstration project. Academic medicine. J Assoc Am Med Colleges. 2005;80(4):339–343. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200504000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tordoff A, Wilson S, Becket G. Definitions of professionalism in pharmacy practice: a systematic review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2009;17:S1A35–36. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hilton S. Medical professionalism: how can we encourage it in our students? The Clinical Teacher. 2004;1(2):69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner P, Hendrich J, Moseley G, Hudson V. Defining medical professionalism: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2007;41(3):288–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denzin NK, Metlin CJ. Incomplete professionalization: The case of pharmacy. Soc Forces. 1966;46:375–381. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freidson E. New York: Dodd, Mead; 1975. Profession of medicine: A study of the sociology of applied knowledge. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson RD. The peril of deprofessionalization. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2004;61(22):2373–2379. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birenbaum A. Reprofessionalization in pharmacy. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16:871–878. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90203-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shuval JT. Attempts at Professionalization of Pharmacy: An Israel Case Study. Soc Sci Med. 1978;12:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwirian PM. Professional Socialization and Disillusionment: The Case of Pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 1974:18–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith M, Messer S, Fincham JE. A Longitudinal Study of Attitude Change in Pharmacy Students During School and Post Graduation. Am J Pharm Educ. 1991;55:30–35. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knapp DE, Knapp DA. Disillusionment in pharmacy students. Soc Sci Med. 1968;1:445–447. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatoum HT, Smith MC. Identifying patterns of professional socialisation for pharmacists during pharmacy schooling and after one year in practice. Am J Pharm Educ. 1987;51:7–17. [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Board of Internal Medicine. [Accessed July 20 2009];Project Professionalism. 1995 Available at: http://www.abim.org/pdf/publications/professionalism.pdf .

- 20.Swick HM, Szenas P, Danoff D, Whitcomb ME. Teaching professionalism in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 1999;282(9):830–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.9.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Embedding Professionalism in Medical Education: Assessment as a Tool for Implementation. Report from an Invitational Conference cosponsored by the AAMC and NBME. 2002 May; [Google Scholar]

- 22.APhA-ASP/AACP-COD Task force on professionalism. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000;40:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammer DP, Berger BA, Beardsley RS, Easton MR. Student professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2003;67(1/4):544–573. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pharmacy Professionalism Toolkit for Students and Faculty Provided by the APhA-ASP/AACP Committee on Student Professionalism. [Accessed July 20, 2009]; Available at: http://www.pharmacist.com/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Professionalism_Toolkit_for_Students_and_Faculty .

- 25.Lerkiatbundit S. Professionalism in Thai pharmacy students. J Soc Admin Pharm. 2000;17(1):51. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lerkiatbundit S. Factor structure and cross-validation of a professionalism scale in pharmacy students. Journal of Pharmacy Teaching. 2005;12(2):25–49. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fung SM, Norton LL, Ferrill MJ, Supemaw RB. Promoting professionalism through mentoring via the internet. Am J Pharm Educ. 1997;61:166–169. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang TS, Fjortoft NF. Developing into a professional: Students’ perspectives. Am J Pharm Educ. 1997;61:83S. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berger BA, Butler SL, Duncan-Hewitt W, Felkey BG, Taylor C, et al. Changing the culture: An institution-wide approach to instilling professional values. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68(1):22. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boyle CJ, Beardsley RS, Morgan JA, de Bittner MR. Professionalism: A determining factor in experiential learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(2):31. doi: 10.5688/aj710231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brehm B, Breen P, Brown B, Long L, Smith R, Wall A, et al. An interdisciplinary approach to introducing professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(4):81. doi: 10.5688/aj700481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bumgarner GW, Spies AR, Asbill CS, Prince VT. Using the humanities to strengthen the concept of professionalism among first-professional year pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71:28. doi: 10.5688/aj710228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chisholm MA, Cobb H, Duke L, McDuffie C, Kennedy WK. Development of an instrument to measure professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70:85. doi: 10.5688/aj700485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duke LJ, Kennedy K, McDuffie CH, Miller MS, Chisholm MA, et al. Student attitudes, values, and beliefs regarding professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2005;69:73. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammer DP. Development and Testing of an Instrument to Assess Behavioural Professionalism of Pharmacy Students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2000;64:141–151. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paik C, Broedel-Zaugg K. Pharmacy students’ opinions on civility and preferences regarding professors. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70:93. doi: 10.5688/aj700488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sylvia LM. Enhancing professionalism of pharmacy students: Results of a national survey. Am J Pharm Educ. 2004;68:71. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldie J, Dowie A, Cotton P, Morrison J. Teaching professionalism in the early years of a medical curriculum: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2007;41:610–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hilton S. Medical professionalism: how can we encourage it in our students? The Clinical Teacher. 2004;1:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Irvine D. The performance of doctors: the new professionalism. Lancet. 1999;353:1174–1177. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)91160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anon Pharmacists near top of ‘most trusted profession’ poll. Pharm J. 2009;282:472. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pharmacy enews. [Accessed 20 August, 2009]; Available at: http://static.rbi.com.au/common/contentmanagement/pharmacy/pdf/backissues/15_06_2009.pdf .

- 43.RPSGB Undergraduate education. [Accessed 20 August, 2009]; Available at: http://www.rpsgb.org.uk/acareerinpharmacy/undergraduateeducation/index.html .

- 44.Pharmacy Board of South Australia. Registration of Pharmacy Students. [Accessed August 20 2009];2009 Available at: http://www.pharmacyboard.sa.gov.au/registrations.htm#studentreg .

- 45.Pharmacy Board of Victoria. Student registration. [Accessed August 20 2009];2009 Available at: http://www.pharmacybd.vic.gov.au/pharmacists_prereg_student.php .

- 46.Roth MT, Zlatic TD. Development of student professionalism. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(6):749–56. doi: 10.1592/phco.29.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown D, Ferrill MJ. The Taxonomy of Professionalism: Reframing the Academic Pursuit of Professional Development. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(4):68. doi: 10.5688/aj730468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill WT. White paper on pharmacy student professionalism. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2000;40:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manasse HR, Stewart JE, Hall RH. Inconsistent socialization in pharmacy — a pattern in need of change. J Am Pharm Assoc. 1975;NS15:616–621. doi: 10.1016/s0003-0465(16)34130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]