Abstract

Drugs with narrow therapeutic index (NTI-drugs) are drugs with small differences between therapeutic and toxic doses. The pattern of drug-related problems (DRPs) associated with these drugs has not been explored.

Objective

To investigate how, and to what extent drugs, with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI-drugs), as compared with other drugs, relate to different types of drug-related problems (DRPs) in hospitalised patients.

Methods

Patients from internal medicine and rheumatology departments in five Norwegian hospitals were prospectively included in 2002. Clinical pharmacists recorded demographic data, drugs used, medical history and laboratory data. Patients who used NTI-drugs (aminoglycosides, ciclosporin, carbamazepine, digoxin, digitoxin, flecainide, lithium, phenytoin, phenobarbital, rifampicin, theophylline, warfarin) were compared with patients not using NTI-drugs. Occurrences of eight different types of DRPs were registered after reviews of medical records and assessment by multidisciplinary hospital teams. The drug risk ratio, defined as number of DRPs divided by number of times the drug was used, was calculated for the various drugs.

Results

Of the 827 patients included, 292 patients (35%) used NTI-drugs. The NTI-drugs were significantly more often associated with DRPs than the non-NTI-drugs, 40% versus 19% of the times they were used. The drug risk ratio was 0.50 for NTI-drugs and 0.20 for non-NTI-drugs. Three categories of DRPs were significantly more frequently found for NTI-drugs: non-optimal dose, drug interaction, and need for monitoring.

Conclusion

DRPs were more frequently associated with NTI-drugs than with non-NTI-drugs, but the excess occurrence was solely related to three of the eight DRP categories recorded. The drug risk ratio is a well-suited tool for characterising the risk attributed to various drugs.

Keywords: Clinical Pharmacy Information Systems, Drug Toxicity, Inpatients, Norway

INTRODUCTION

Drug-related problems (DRPs) have been found to be associated with increased morbidity, mortality and health costs.1-3 Therefore, preventing DRPs would benefit both patients and society. Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI-drugs) are drugs with small differences between their therapeutic and toxic doses, implying that small changes in dosage or interactions with other drugs could cause adverse effects. Although an universally accepted definition of NTI-drugs has not been agreed upon, the definitions used in the literature do not vary much.4 Moreover, despite the lack of definite lists of NTI-drugs, the understanding of which drugs should belong to the NTI group are by and large similar among drug experts.

NTI-drugs have been shown to be a major cause of emergency department visits.5 Many patients admitted to hospitals are severely ill and have conditions that may influence the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs administered to them. Accordingly, hospitalisation might increase the risk of DRPs, and patients using NTI-drugs are probably at particular risk. However, the relationship between use of NTI-drugs and occurrence of different DRPs in hospitalised patients is not known. The study aimed to investigate how and to what extent NTI-drugs, as compared with other drugs, are associated with DRPs in hospitalised patients and, furthermore, to develop a tool for the calculation of risk for DRPs.

METHODS

Patients and design

A prospective multicentre design was applied. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics. From May to December 2002, clinical pharmacists enrolled patients admitted to eight departments in five general hospitals in Norway. The departments involved were six departments of internal medicine (cardiology, lung diseases and geriatric wards) and two departments of rheumatology. The clinical pharmacists usually visited the departments 3-5 days per week (one department 2 days per week), weekends not included. All patients who were in the departments on the days the clinical pharmacists attended the multidisciplinary health care team were eligible and were included consecutively. As patients admitted during the weekend were generally hospitalised for longer than the weekend, nearly all hospitalised patients (estimated to at least 95%) were captured and recruited to the study. In this way, selection bias should have been avoided. Emergency departments were not included. Readmitted patients were excluded.

The patients were followed prospectively during their hospital stay. Clinical pharmacists collected the data in a uniform way using a standard data recording form that had been designed, tested, and found applicable for the participating departments. Data were collected from medical charts, medical records, multidisciplinary team meetings with physicians and nurses, and also during contact with patients. The information collected was entered into a database constructed for the study.

The following data were recorded for each patient: age, gender, presenting complaints, all drugs used at admittance and during hospital stay, medical history, and results of laboratory tests. Further, specific factors that are assumed to increase the risk for DRPs were recorded. These were: the use of 5 or more drugs at admission), severely reduced renal function (glomerular filtration rate below 30 ml/min as calculated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) formula),6 reduced liver function (aspartate amino transferase or alanine aminotransferase three times above normal values), confirmed diabetes mellitus, cardiac failure.

The drugs were classified according to the ATC-classification system, which classify drugs according to their anatomical, therapeutic and chemical properties and is used among others by the WHO Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring (the Uppsala Centre).7

Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index

The therapeutic window of a certain drug reflects the concentration range that provides efficacy without unacceptable toxicity.4 Narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs have a narrow therapeutic window, hence doses must be titrated carefully and tight monitoring is usually required. Generally approved lists of NTI-drugs are not available in the literature, but in general, drugs having a small difference between plasma concentration range resulting in efficacy and toxicity are named NTI-drugs.4 We defined the following drugs to be NTI-drugs: aminoglycosides, ciclosporin, carbamazepine, digoxin, digitoxin, flecainide, lithium, phenytoin, phenobarbital, rifampicin, theophylline and warfarin. The drugs were divided into NTI-drugs and non-NTI-drugs (these being all other drugs than those mentioned above). Patients using one or more NTI-drugs were named NTI-users and patients not using NTI-drugs non-NTIusers.

Drug-related problems

The pharmacist identified DRPs among the patients and thereafter discussed the findings with the multidisciplinary teams lead by physicians. DRPs were defined in accordance with the definition of Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe: “a drug-related problem is an event or circumstance involving drug therapy that actually or potentially interferes with desired health outcomes”.8,9 In this study eight categories were used for classification of DRPs: need for an additional drug, unnecessary drug, non-optimal drug, non-optimal dose, no further need of drug, drug interaction, need for monitoring and adverse drug reaction (ADR). We have previously reported further details concerning the classification, occurrence and management of DRPs. 10,11

Drug risk ratio

To identify “drugs at risk”, we introduced a drug risk ratio for the different drugs, which is the number of DRPs for a given drug divided by the number of times the drug was used.

A drug might cause one or more DRPs. Most often only one DRP was identified for each prescribed drug. Sometimes more than one DRP was found to be linked to the drug and often these DRPs were interdependent. For example, when an aminoglycoside is given in too high dose, there is a need for monitoring, that is to say two DRPs exist: non-optimal dose and need for monitoring. In these cases, where more than one DRP was associated with a drug, all counted DRPs were used as the basis for the drug risk ratio calculation.

Another way of calculating a drug risk ratio could be to register the mere occurrence of DRPs linked to a certain drug in a given patient and count this as one DRP, even when more than one DRP could be identified. This approach is not as logical and straightforward as our chosen method. Nevertheless, calculations were also done this way and, essentially, the results remained the same (data not shown).

Statistical analysis

A database was established and analysed using SPSS 14.0 for Windows. Descriptive statistics are shown as means and frequencies with standard deviations. P values less than 0.05 (p<0.05) were accepted as statistically significant. To test for differences between groups, Mann-Whitney tests were used for continuous variables, while chi-squared tests were used for categorical variables. In addition, we performed a log-linear regression with number of DRPs per patient as the dependent variable, and being a NTI-user and other risk factors presented below as independent variables. This was done to study whether NTI-users have an increased risk of DRPs after also adjusting for the other risk factors. The log-transformation was applied to ensure that the residuals were approximately normally distributed.

RESULTS

The study included 827 patients, 58.6% female and 41.4% male, with a mean age of 70.8 (SD=17.2, range 15-98). 292 (35%) patients used at least one NTI-drug, while 535 (65%) did not use NTI-drugs (Table 1). A total of 217 patients (74% of the NTI-users) had one NTI-drug, whereas 69 (24%) used two and 6 (2%) used three NTI-drugs. More NTI-users than non-NTI-users had at least one DRP, 235 of the 292 NTI-users (80%) versus 356 of the 535 non-NTI-users (67%).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, number of drugs, number of clinical/pharmacological risk factors and number of drug-related problems in hospitalised patients. NTI-users: patients using drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI), Non-NTI-users: patients not using drugs with a narrow therapeutic index

| NTI-users N = 292 | Non-NTI-users N = 535 | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) [range] | Mean (SD) [range] | ||

| Age | 75.2 (12.7) | 68.4 (18.7) | p<0.01 |

| No. drugs on admission | 5.6 (3.2) [0-15] | 4.0 (3.0) [0-16] | p<0.01 |

| No. drugs started in hospital | 5.1 (3.3) [0-16] | 3.4 (2.6) [0-13] | p<0.01 |

| Total no. of drugs | 10.7 (4.3) [0-16] | 7.3 (3.9) [0-16] | p<0.01 |

| No. DRPsa per patient | 2.7 (2.5) [0-16] | 1.5 (1.7) [0-11] | p<0.01 |

| No. selectedb DRPs per patient | 1.6 (1.8) [0-10] | 0.6 (1.0) [0-7] | p<0.01 |

| % (No.) | % (No.) | ||

| Gender females | 53 % (156) | 61 % (329) | p=0.02 |

| Clinical risk factors | |||

| Diabetes | 14 % (41) | 10 % (52) | p=0.06 |

| Heart failure | 32 % (92) | 11 % (57) | p<0.01 |

| Renal impairment, GFR<30 ml/min | 7 % (19) | 4 % (22) | p=0.13 |

DRP categories: need for additional drug, unnecessary drug, non-optimal drug, non-optimal dose, drug interaction, need for monitoring, no further need for drug, adverse drug reaction

Selected DRPs: not optimal dose, drug interaction, need for monitoring

Risk factors for occurrence of DRPs are outlined in Table 2. Use of NTI-drugs, number of drugs at admission, number of drugs introduced in hospital and presence of renal failure were independent risk factors.

Table 2.

Risk of DRPs in 827 hospitalised patients in relation to different risk factors. Analyses done by log-linear regression with DRPs as a dependent variable and the following as independent variables: gender, age, number of drugs on admission, number of drugs introduced in hospital, use of NTI-drugs, occurrence of renal impairment, diabetes and heart failure.

| Independent variable | Univariate RR (p value) | Multivariate RR (p value) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (female = 1) | 1.04 (=0.44) | - |

| Age | 1.01 (<0.01) | - |

| No. of drugs used on admission | 1.07 (<0.01) | 1.06 (<0.01) |

| No. of drugs introduced at hospital | 1.08 (<0.01) | 1.07 (<0.01) |

| Using NTI-drug(s) | 1.35 (<0.01) | 1.11 (=0.02) |

| Renal impairment, GFR < 30 ml/min | 1.46 (<0.01) | 1.22 (=0.02) |

| Diabetes | 1.20 (<0.01) | - |

| Heart failure | 1.31 (<0.01) | - |

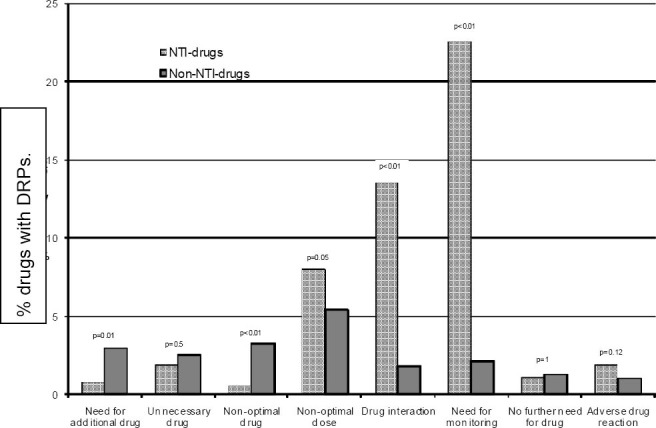

The 292 NTI-users used 376 NTI-drugs, which represented 12% of their drugs and 5% of the total number of drugs used by all patients. DRPs were significantly more often connected to NTI-drugs than to non-NTI-drugs, with a drug risk ratio of 0.50, compared to 0.20 (p < 0.01), (Table 3). Three categories of DRPs were more frequently found for NTI-drugs; these were non-optimal dose, drug interaction, and need for monitoring (Figure 1). The most frequent DRP associated with NTI-drugs, need for monitoring, was observed in 23% of the instances the NTI-drugs were used, whereas the corresponding figure was 2% for non-NTI-drugs. NTI-drugs were connected to drug interactions and non-optimal dose in 14% and 8% of the times they were used, while the figures for non-NTI-drugs were 2% and 5%.

Table 3.

Number of times the drugs were used, number of drugs with drug-related problems (DRPs), and drug risk ratio for drugs with and without a narrow therapeutic index (NTI)

| N times used | Number of drugs with DRPsa (% of drugs) | Total Number of DRPsa | Drug risk ratiob | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-NTI-drugs | 6778 | 1258 (19 %) | 1386 | 0.20 |

| NTI-drugs | 376 | 149 (40 %) | 189 | 0.50 |

| Total | 7154 | 1407 (20 %) | 1676 |

DRP categories: need for additional drug, unnecessary drug, non-optimal drug, non-optimal dose, drug interaction, need for monitoring, no further need for drug, adverse drug reaction

Number of DRPs/number of times the drug is used

Figure 1.

Frequencies of various types of drug-related problems (DRPs) related to drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI-drugs, N = 376) and to other drugs (non-NTI-drugs, N = 6778) among 827 hospitalised patients. Differences between NTI-drugs and non-NTI-drugs are shown by p values

The drug risk ratios for different NTI-drugs were high and markedly higher than the ratios for the most frequently used drugs (Figure 2). Some non-NTI-drugs, most of them with relatively low use, also had high drug risk ratios, as a result of relatively high frequencies of a wide range of DRPs. They did not exhibit a specific DRP pattern corresponding to that found for NTI-drugs.

Figure 2.

Times used and drug risk ratio for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI-drugs)a and other drugs (non-NTIdrugs) among 827 hospitalised patients

a Drugs used less than 5 times are not included in the figure. In the following, number of times used and number of DRPs are shown in brackets: ciclosporin (2/4), digoxin (1/0), flecainide (1/1), gentamicin (3/4), lithium (3/7), phenobarbital (3/3), phenytoin (1/0), rifampicin (3/1). In total, those drugs were used 17 times and were associated with 20 DRPs, which equals a drug risk ratio of 1.2.

DISCUSSION

Our study showed that a high proportion of hospitalised patients (35%) used NTI-drugs, a proportion that is markedly higher than that reported in ambulatory care in Norway, where a figure of 3% was found.12 Also, DRPs were significantly more often linked to the use of NTI-drugs than to the use of non-NTI-drugs. These findings demonstrate a particular need for drug surveillance in hospitals to avoid serious consequences of DRPs.5,13

Furthermore, our study, which is the first to delineate the DRP pattern of NTI-drugs, showed that the DRPs non-optimal dose, drug interaction, and need for monitoring should receive particular attention. Among the eight DRP categories monitored, these three are of such a nature that they could be expected to be connected to NTI-drugs. Indeed, when the NTI-drugs were used, the three mentioned DRPs showed very high frequencies, and markedly higher than those found for the other DRPs. The other DRPs exhibited rather similar patterns with regard to the extent to which they were associated with the NTI-drugs and the non-NTI-drugs. Thus, it is the narrow therapeutic window that emerges as a problem when NTI-drugs are administered in hospitalised patients.

The NTI-users were different from the non-NTIusers with regard to age, comorbidity, and use of drugs. Therefore we investigated the possibility that the difference in occurrence of DRPs, and consequently in drug risk ratios, might be accounted for by such differences. It was confirmed by applying multivariate analysis that use of NTI-drugs independently predicted occurrence of DRPs. We have earlier elaborated on the risks of DRPs in general and in relation to polypharmacy and renal impairment.14,15

With regard to definitions of DRPs it should be noted that these have varied over the years. The PCNE definition of DRPs,9 which we also used, includes both potential and actual problems. The general definition has not been changed since 2002 the year we collected the DRP data. When it comes to the categorisation into specific DRPs, a variety of classification systems for DRPs are available, and discussions on which to prefer are still ongoing.8,16 The PCNE classification consists of six main problem domains and 21 problem categories. Because our study was performed bedside in clinical practice we found it necessary to simplify and we decided to use eight DRP categories. After testing in a pilot study this approach was judged to be practical and convenient for clinical use.

Recently we introduced the drug risk ratio as a novel way of assessing a drug’s risk for occurrence of DRPs.17 When applying this calculation tool we found that the NTI-drugs largely showed high ratios and also that comparisons with other drugs could easily be undertaken. The most frequently used non-NTI-drugs exhibited low ratios but some non-NTI-drugs, which were less used, had relatively high ratios due to a wide variety of causes. Although the non-NTI-drugs with high ratios did not show a specific DRP pattern they should achieve special attention along with the NTI-drugs.

How could the information obtained in the present study be used in clinical practice? One possibility is to make lists of alert medicines and include them in electronic prescribing support systems. NTI-drugs would constitute an essential part of such a list and it might be supplemented with other drugs that for various reasons have high drug risk ratios. Electronic prescribing has been shown to improve the prescription quality by reducing both prescribing errors and the need for pharmacists’ clinical interventions.18 Introduction of drug alerts into the prescribing systems may further simplify the identification of patients with potential drug problems and offer an additional improvement.

A limitation of our study is the fact that it was undertaken in hospitalised patients, most of whom were acutely ill. Thus the results are relevant for this patient population and cannot be extrapolated to outpatients who are in a more stable phase. More clinical practice research is needed to test whether focus on the NTI-drugs would be helpful in the risk assessment for other types of patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the clinical pharmacists Elspeth Walseth, Bodil Jahren Hjemaas, Tine Flindt Vraalsen, Piia Pretsch, and Frank Jørgensen, and our colleagues in the multidisciplinary teams of the participating departments.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None to declare.

The study was carried out at the University of Oslo and partly funded by The Norwegian Community Pharmacy Foundation and The Norwegian Pharmacy Associations’ Foundation. Both are nonprofit organisations.

Contributor Information

Hege S. Blix, Lovisenberg Diakonale Hospital Pharmacy, Oslo / Department of Pharmacotherapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo / Department of Pharmacoepidemiology, Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Oslo (Norway)

Kirsten K. Viktil, Diakonhjemmet Hospital Pharmacy / Department of Pharmacotherapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo. Oslo (Norway)

Tron A. Moger, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Department of Biostatistics, University of Oslo. Oslo (Norway)

Aasmund Reikvam, Department of Pharmacotherapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo. Oslo (Norway).

References

- 1.Ernst FR, Grizzle AJ. Drug-related morbidity and mortality: updating the cost-of-illness model. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2001;41:192–199. doi: 10.1016/s1086-5802(16)31229-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winterstein AG, Sauer BC, Hepler CD, Poole C. Preventable drug-related hospital admissions. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1238–1248. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel P, Zed PJ. Drug-related visits to the emergency department: how big is the problem? Pharmacotherapy. 2002;22:915–923. doi: 10.1592/phco.22.11.915.33630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman, Gilman's . Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics. 11. Ed. Chapter 1. The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2005. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. ISBN:0-07-142280-3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Budnitz DS, Shehab N, Kegler SR, Richards CL. Medication use leading to emergency department visits for adverse drug events in older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:755–765. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MDRD calculator. National Kidney Foundation. [last accessed 2009 May 22];2006 http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/gfr_calculator.cfm .

- 7.Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre; 2005. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. ATC Index with DDDs 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Mil JW, Westerlund LO, Hersberger KE, Schaefer MA. Drug-related problem classification systems. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:859–867. doi: 10.1345/aph.1D182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE) [last accessed 2009 Dec.8]; http//www.pcne.org/)

- 10.Blix HS, Viktil KK, Reikvam A, Moger TA, Hjemaas BJ, Pretsch P, Vraalsen TF, Walseth EK. The majority of hospitalized patients have drug-related problems: results from a prospective study in general hospitals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60:651–658. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blix HS, Viktil KK, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Characteristics of drug-related problems discussed by hospital pharmacists in multidisciplinary teams. Pharm World Sci. 2006;28:152–158. doi: 10.1007/s11096-006-9020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norwegian prescription database, NorPD. [last accessed 2009 May 22]; http://www.norpd.no/

- 13.George J, Munro K, McCaig D, Stewart D. Risk factors for medication misadventure among residents in sheltered housing complexes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:171–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02799.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viktil KK, Blix HS, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Polypharmacy as commonly defined is an indicator of limited value in the assessment of drug-related problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02744.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blix HS, Viktil KK, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Use of renal risk drugs in hospitalized patients with impaired renal function--an underestimated problem? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3164–3171. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Björkman IK, Sanner MA, Bernsten CB. Comparing 4 classification systems for drug-related problems: processes and functions. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2008;4:320–331. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blix HS, Viktil KK, Moger TA, Reikvam A. Risk of drug-related problems for various antibiotics in hospital: assessment by use of a novel method. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;8:834–841. doi: 10.1002/pds.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donyai P, O’Grady K, Jacklin A, Barber N, Franklin BD. The effects of electronic prescribing on the quality of prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:230–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]