Abstract

Background

It is considered standard practice to use disposable or patient-dedicated stethoscopes to prevent cross-contamination between patients in contact precautions and others in their vicinity. The literature offers very little information regarding the quality of currently used stethoscopes. This study assessed the fidelity with which acoustics were perceived by a broad range of health care professionals using three brands of stethoscopes.

Methods

This prospective study used a simulation center and volunteer health care professionals to test the sound quality offered by three brands of commonly used stethoscopes. The volunteer’s proficiency in identifying five basic ausculatory sounds (wheezing, stridor, crackles, holosystolic murmur, and hyperdynamic bowel sounds) was tested, as well.

Results

A total of 84 health care professionals (ten attending physicians, 35 resident physicians, and 39 intensive care unit [ICU] nurses) participated in the study. The higher-end stethoscope was more reliable than lower-end stethoscopes in facilitating the diagnosis of the auscultatory sounds, especially stridor and crackles. Our volunteers detected all tested sounds correctly in about 69% of cases. As expected, attending physicians performed the best, followed by resident physicians and subsequently ICU nurses. Neither years of experience nor background noise seemed to affect performance. Postgraduate training continues to offer very little to improve our trainees’ auscultation skills.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that using low-end stethoscopes to care for patients in contact precautions could compromise identifying important auscultatory findings. Furthermore, there continues to be an opportunity to improve our physicians and ICU nurses’ auscultation skills.

Keywords: auscultation skills, acoustics, training programs

Introduction

Contact precautions are commonly implemented in hospitals to prevent the spread of multidrug resistant (MDR) bacteria from infected or colonized patients to other individuals in their vicinity.1–3 Those precautions include the use of dedicated and sometimes disposable medical equipment while caring for those patients. Examples of disposable medical equipment being used in those circumstances include blood pressure cuffs, pulse oximetry probes, and stethoscopes.

Multiple brands of stethoscopes are commercially available; prices, and potentially quality, vary. Multiple health care professionals in our medical center have raised concerns over the quality of some of the brands of stethoscopes used to care for patients in contact precautions. In addition, the literature offers very little information about the fidelity with which acoustics are conducted to the examiners’ ears using the available stethoscopes.4

The aim of this prospective study was to report how well three different brands of stethoscopes perform in the hands of a diverse group of health care professionals in a controlled setting. Furthermore, the accuracy of health care professionals at different levels of expertise was tested in identifying common auscultatory sounds.

Methods

This study had two parts; the first was carried out at SimCentral, the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center (TTUHSC) simulation center in Amarillo, TX, USA, and the second was performed at the Northwest Texas Hospital (NWTH) medical intensive care unit (MICU) in Amarillo. The investigational review boards at TTUHSC and NWTH approved the study’s protocol.

Health care professionals from the following groups were invited via email to participate in the study:

Attending physicians of the Internal Medicine department at TTUHSC.

Resident physicians of the Internal Medicine department at TTUHSC.

NWTH adult intensive care unit (ICU) nurses.

In the first part of the study, interested volunteers from the above groups contacted one of the study investigators via email or phone to set an appointment at the simulation center for conducting the study. In the second part of the study, NWTH adult ICU nurses who did not participate in the first part were invited again to volunteer after the study simulator was moved from the simulation center to an empty MICU room. The second part of the study was conducted 2 weeks after the first part and intended to test the effect of MICU background noise on ICU nurses’ auscultation proficiency using the same three brands of stethoscopes.

The study protocol used the following equipment:

Laerdal SimMan 3G model (Laerdal Medical, Stavanger, Norway)

Proscope 665 (stethoscope, brand 1), a disposable stethoscope by American Diagnostic Corporation (Hauppauge, NY, USA)

Lightweight dual-head stethoscope (brand 2) by Owens and Minor (Mechanicsville, VA, USA)

Littmann Cardiology III stethoscope (brand 3) by 3M (St Paul, MN, USA)

Three pairs of Prestige earpieces (Prestige Medical, Northridge, CA, USA) to replace regular earpieces on all of the above stethoscopes

Regular sleeping masks.

The volunteers were asked to wear a regular sleeping mask so they would not be able to see the stethoscopes being tested. The investigator placed the stethoscopes in the volunteers’ ears and placed the diaphragm piece of the stethoscope on the simulator model’s chest or abdomen. The volunteers were asked five questions per brand of stethoscopes; three related to pulmonary sounds, one related to heart sounds, and the last related to bowel sounds. Multiple potential answers were given to the volunteer to choose from based on what they heard. For lung sounds, the potential answers given were stridor, wheezing, crackles, and normal breath sounds. For heart sounds, potential answers given were holosystolic murmur, diastolic murmur, gallop, and normal heart sounds. For abdominal sounds, potential answers given were hyperdynamic bowel sounds, normal bowel sounds, hypoactive bowel sounds, and no bowel sounds. Stethoscope brand 1 was tested first, followed by brands 2 and 3.

The following auscultatory findings were the correct answers and were tested in the same order for all volunteers:

Stridor

Wheezing

Coarse crackles (crackles)

Holosystolic murmur (systolic murmur)

Hyperdynamic bowel sounds.

The simulator model was set to make the above sounds at volume level 3. The model volume scale runs between 0 and 9. If the volunteer was unable to hear the sound being tested, then the volume level was increased in increments of two till he/she was able to give an answer. The volunteer group; whether the volunteer was an attending physician, ICU nurse, or resident physician (postgraduate trainee) and his/her level of training; postgraduate year (PG-1, PG-2, or PG-3), and the volunteer’s answers were recorded in a data collection sheet.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were expressed as a mean with its associated standard deviation. Categorical data were expressed as a proportion with its corresponding percentage. Comparison of proportion of correct detection of the sounds across subgroups was carried out using chi-square test (with continuity correction wherever necessary). Assessment of linear trend in proportion across subgroups that was in natural order was carried out using trend chi-square test. Fisher’s exact test was also resorted to for comparison of proportions when the validity of chi-square test was not met. Unpaired t-test was used to compare the means of two groups. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 84 health care professionals (ten attending physicians, 35 resident physicians, and 39 ICU nurses) participated in the study. Among the attending physicians, there were two intensivists and eight general internists. There were 13 PG-1, six PG-2, and 16 PG-3 resident physicians. Twenty-two ICU nurses with 6.6±5.1 years of experience volunteered at the simulation center and 17 ICU nurses with 3.9±3.4 years of experience volunteered at the MICU. The difference in years of experience was not quite statistically significant (P=0.06). Each of the participants used the three different brands of stethoscope sequentially. The participants were not given any feedback regarding their answers.

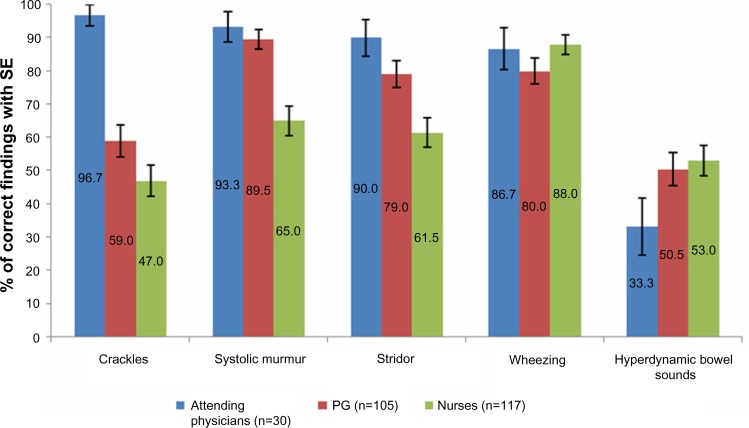

The correct detection rates of the five auscultation sounds are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. The most correctly detected auscultation problem was wheezing followed by systolic murmur, stridor, crackles, and hyperdynamic bowel sounds. The overall correct identification of all the sounds put together was 68.6%.

Table 1.

Overall identification rate of the five auscultatory sounds

| Condition | Identification, n (%)

|

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrong | Correct | ||

| Crackles | 106 (42.1) | 146 (57.9) | 252 (100.0) |

| Wheezing | 39 (15.5) | 213 (84.5) | 252 (100.0) |

| Stridor | 70 (27.8) | 182 (72.2) | 252 (100.0) |

| Systolic murmur | 54 (21.4) | 198 (78.6) | 252 (100.0) |

| Hyperdynamic bowel sounds | 127 (50.4) | 125 (49.6) | 252 (100.0) |

| Total | 396 (31.4) | 864 (68.6) | 1,260 (100.0) |

Figure 1.

Correct detection rates of the five ausculation sounds.

Abbreviation: SE, stethoscopes.

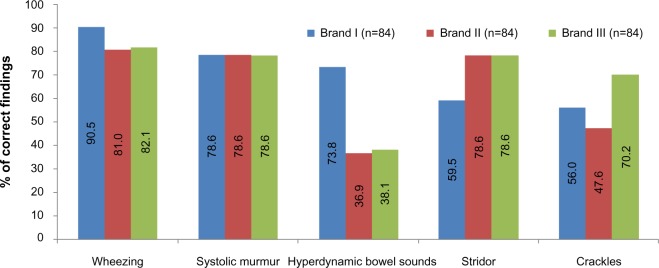

The accuracy of detecting five auscultatory sounds with three stethoscope brands is shown in Table 2 and Figure 2. Stethoscope brand 3 was more consistent in identifying the correct auscultatory sound.

Table 2.

Accuracy of detection of five auscultatory sounds by stethoscope brands I, II, and III

| Condition | Brand of stethoscope

|

χ2 | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (n=84), # correct (%) |

II (n=84), # correct (%) |

III (n=84), # correct (%) |

|||

| Crackles | 47 (56.0) | 40 (47.6) | 59 (70.2) | 9.02 | 0.011 |

| Wheezing | 76 (90.5) | 68 (81.0) | 69 (82.1) | 3.46 | 0.177 |

| Stridor | 50 (59.5) | 66 (78.6) | 66 (78.6) | 10.13 | 0.006 |

| Systolic murmur | 66 (78.6) | 66 (78.6) | 66 (78.6) | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Hyperdynamic bowel sounds | 62 (73.8) | 31 (36.9) | 32 (38.1) | 29.56 | <0.001 |

Figure 2.

Correct detection rates of the five auscultation sounds by using stethoscope brand I, II, and III.

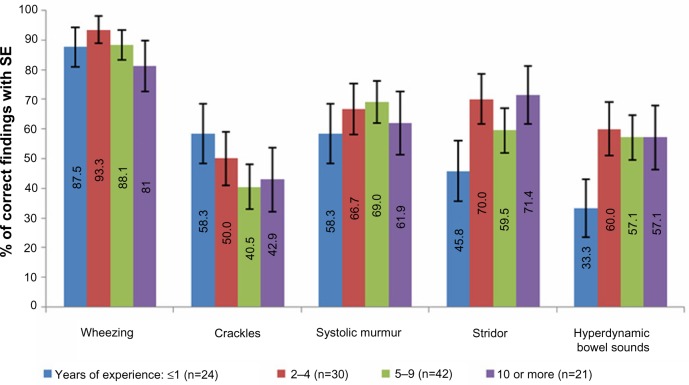

The correct detection rates of the five auscultatory sounds among attending physicians, resident physicians, and ICU nurses are depicted in Table 3 and Figure 3. Attending physicians were most accurate, followed by resident physicians and then by ICU nurses.

Table 3.

Accuracy of detection of five auscultatory sounds by three groups of health care personnel

| Condition | Group

|

χ2 (P-value) |

Trend χ2 (P-value) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attending physicians (n=30) # correct (%) |

PG Trainees (n=105) # correct (%) |

Nurses (n=117) # correct (%) |

|||

| Crackles | 29 (96.7) | 62 (59.0) | 55 (47.0) | 24.3 (<0.001) | 20.8 (<0.001) |

| Wheezing | 26 (86.7) | 84 (80.0) | 103 (88.0) | 2.85 (0.240) | 0.8 (0.377) |

| Stridor | 27 (90.0) | 83 (79.0) | 72 (61.5) | 13.8 (<0.001) | 13.5 (<0.001) |

| Systolic murmur | 28 (93.3) | 94 (89.5) | 76 (65.0) | 24.2 (<0.001) | 21.0 (<0.001) |

| Hyperdynamic bowel sounds | 10 (33.3) | 53 (50.5) | 62 (53.0) | 3.75 (0.154) | 2.67 (0.103) |

Abbreviation: PG, postgraduate.

Figure 3.

Correct detection rates of the five auscultation sounds by attending physicians, resident physicians, and ICU nurses.

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; SE, stethoscopes; PG, postgraduate trainees.

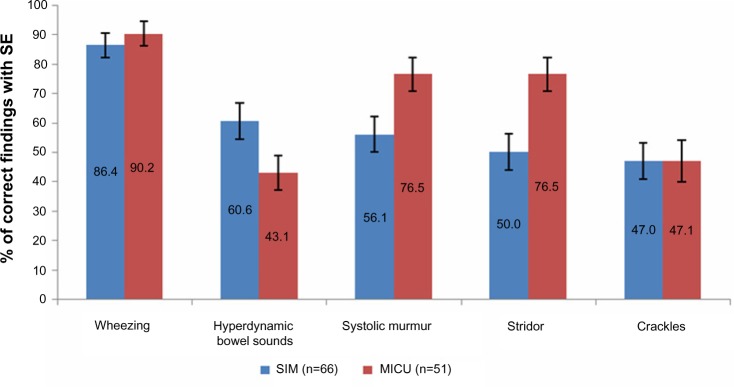

The accurate detection rates of the five sounds by ICU nurses in the simulation center compared to the MICU are presented in Table 4 and Figure 4. The results showed improvement in their performance, especially in detecting systolic murmurs and stridor.

Table 4.

Accuracy of detection of five auscultation sounds by ICU nurses at the simulation center and the MICU

| Condition | Nurses’ location

|

χ2 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SimCentral (n=66) # correct (%) |

MICU (n=51) # correct (%) |

|||

| Crackles | 31 (47.0) | 24 (47.1) | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Wheezing | 57 (86.4) | 46 (90.2) | 0.12 | 0.729 |

| Stridor | 33 (50.0) | 40 (76.5) | 7.44 | 0.004 |

| Systolic murmur | 37 (56.1) | 40 (76.5) | 4.41 | 0.036 |

| Hyperdynamic bowel sounds | 40 (60.6) | 40 (43.1) | 2.86 | 0.091 |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; MICU, medical intensive care unit.

Figure 4.

Correct detection rates of the five auscultation sounds by ICU nurses in the simulation center and MICU.

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; MICU, medical intensive care unit; SE, stethoscopes; SIM, simulation center.

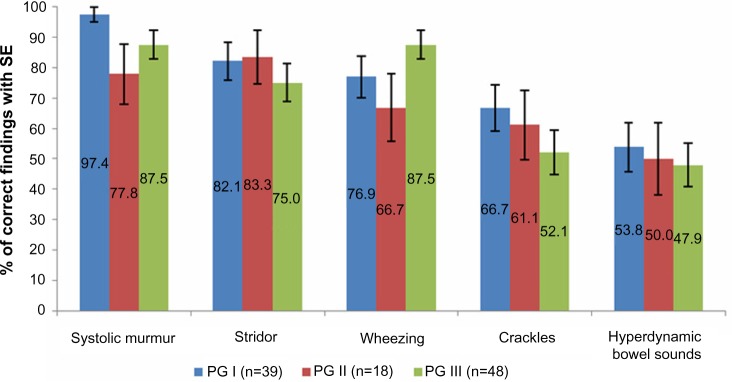

The correct detection rates of the five sounds by resident physicians at PG-1, PG-2, and PG-3 levels of training is depicted in Table 5 and Figure 5. As can be seen from the table, the level of training does not seem to have any effect on the accuracy of detection of any of the five sounds.

Table 5.

Accuracy of detection of five auscultation sounds by the resident physicians’ level of training

| Condition | Level of training PG trainees

|

χ2 (P-value) |

Trend χ2 (P-value) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I (n=39) # correct (%) |

II (n=18) # correct (%) |

III (n=48) # correct (%) |

|||

| Crackles | 26 (66.7) | 11 (61.1) | 25 (52.1) | 1.93 (0.381) | 1.89 (0.169) |

| Wheezing | 30 (76.9) | 12 (66.7) | 42 (87.5) | 3.92 (0.141) | 1.65 (0.198) |

| Stridor | 32 (82.1) | 15 (83.3) | 36 (75.0) | 0.89 (0.642) | 0.67 (0.412) |

| Systolic murmur | 38 (97.4) | 14 (77.8) | 42 (87.5) | 5.46 (0.065) | 2.02 (0.156) |

| Hyperdynamic bowel sounds | 21 (53.8) | 9 (50.0) | 23 (47.9) | 0.31 (0.859) | 0.30 (0.586) |

Notes: I, II and III are post graduate trainees in their first, second and third years of training.

Abbreviation: PG, postgraduate.

Figure 5.

Correct detection rates of the five auscultation sounds by the resident physicians’ level of training.

Notes: I, II and III are post graduate trainees in their first, second and third years of training.

Abbreviations: PG, postgraduate; SE, stethoscopes.

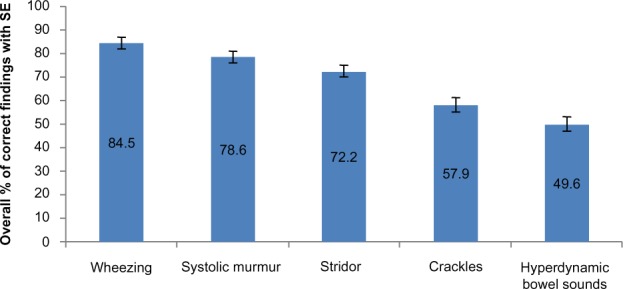

The accurate detection rates of the five sounds by ICU nurses with different years of experience are depicted in Table 6 and Figure 6. As can be seen from the table, years of experience do not seem to have any effect on the accuracy of detecting any of the five sounds.

Table 6.

Accuracy of detection of five auscultation sounds by ICU nurses’ level of experience

| Condition | Years’ experience

|

χ2 (P-value) |

Trend χ2 (P-value) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1 (n=24) # correct (%) |

2–4 (n=30) # correct (%) |

5–9 (n=42) # correct (%) |

≥10 (n=21) # correct (%) |

|||

| Crackles | 14 (58.3) | 15 (50.0) | 17 (40.5) | 9 (42.9) | 2.21 (0.530) | 1.73 (0.188) |

| Wheezing | 21 (87.5) | 28 (93.3) | 37 (88.1) | 17 (81.0) | 1.81 (0.614) | 0.63 (0.428) |

| Stridor | 11 (45.8) | 21 (70.0) | 25 (59.5) | 15 (71.4) | 4.35 (0.226) | 1.76 (0.185) |

| Systolic murmur | 14 (58.3) | 20 (66.7) | 29 (69) | 13 (61.9) | 0.90 (0.826) | 0.15 (0.699) |

| Hyperdynamic bowel sounds | 8 (33.3) | 18 (60.0) | 24 (57.1) | 12 (57.1) | 4.75 (0.191) | 2.25 (0.134) |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

Figure 6.

Correct detection rates of the five auscultation sounds by ICU nurses’ level of experience.

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; SE, stethoscopes.

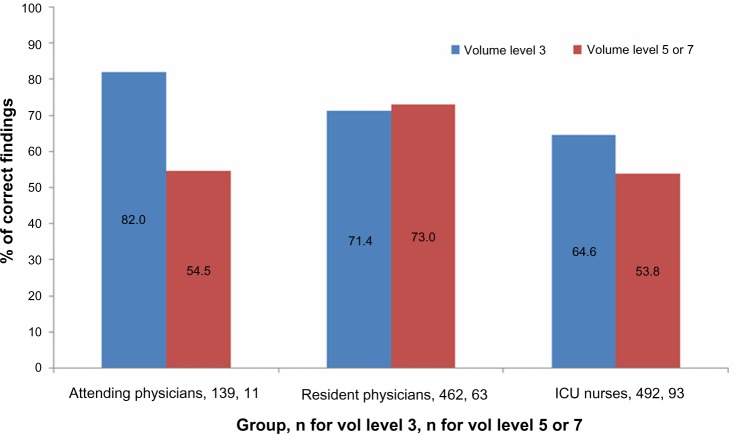

The accuracy of detecting the five sounds and volume level are shown in Table 7 and Figure 7. The majority of the personnel used volume level 3 (1,093 out of 1,260 occasions, 86.7%). Volume level 5 was used on 11.6% of the occasions, and volume level 7 on 1.7% of the occasions. Hence, volume levels 5 and 7 were pooled together for analysis. The overall correct detection rate with volume level 3 was 69.7% and 61.1% with volume level 5 or more; it appears the detection rate was slightly higher with volume level 3, P=0.032.

Table 7.

Accuracy of detection of five auscultation sounds by volume levels

| Group | Volume level

|

χ2 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 # correct (%) |

5 or 7 # correct (%) |

|||

| Attending physicians | 114/139 (82.0) | 6/11 (54.5) | 3.2 | 0.072 (Fisher’s exact, 0.044) |

| Resident physicians | 330/462 (71.4) | 46/63 (73.0) | 0.013 | 0.910 |

| ICU Nurses | 318/492 (64.6) | 50/93 (53.8) | 3.51 | 0.061 |

| Overall | 762/1,093 (69.7) | 102/167 (61.1) | 4.62 | 0.032 |

Figure 7.

Correct detection rates of five auscultation sounds by volume levels.

Abbreviations: vol, volume; PG, postgraduate.

Discussion

In this study, we used a Laerdal SimMan 3G manikin to assess the sound quality offered by three brands of commonly used stethoscopes and to test physicians’ and nurses’ proficiency in identifying common ausculatory sounds. Our cohort volunteers detected all tested sounds correctly in about 69% of cases. As expected, attending physicians did best, followed by resident physicians and subsequently by ICU nurses. Wheezing was picked up correctly in almost 90% of occasions, while systolic murmur, stridor, and crackles were diagnosed in 79%, 72%, and 58% of cases, respectively. In terms of stethoscope fidelity, the high-end stethoscope (brand 3) was more consistent across the board, while stethoscope brands 1 and 2 were less reliable in facilitating the identification of crackles. Neither years of experience nor background noise seem to have affected performance. Postgraduate training continues to offer very little to improve trainees’ auscultation skills. There is a clear opportunity to advance our trainees and ICU nurses’ auscultation skills. Moreover, using low-end stethoscopes could compromise identifying important auscultatory findings.

Stethoscopes are used to assess the subtleties of cardiac and pulmonary sounds and to determine the presence of bowel sounds.4 Stethoscope price is based on the quality of the design, materials used, comfort of fitting, and brand name.5,6 Thus, price alone might not be reflective of superior sound quality. Several previous attempts have been made to test the audio performance of a broad range of stethoscopes.4–7 These laboratory studies have indicated that the stethoscope tube length and diameter do not make a difference that is detectable by the human ear. They also showed that chest piece shape, angularity of conducting channels, and earpiece fitting have greater bearing on the sound transmission differences among stethoscopes. In an acoustic lab, Callahan et al tested 39 brands of stethoscopes’ audio loss while transmitting an audio signal from one end of the stethoscope to the earpiece.4 Neither price nor brand predicted superior performance; some low-end stethoscopes performed better than the higher-end ones. Furthermore, new computerized procedures like phonocardiography signal analysis are being developed to objectively assess auscultatory findings.8,9 Those procedures, once standardized, might help in testing different stethoscopes’ quality.

None of the above efforts gave our clinicians clear guidance on which stethoscope is better; stethoscope selection continues to rely on price and popularity. This and the concerns raised by our staff regarding some of the stethoscope brands used in our hospitals motivated the investigators to use our local resources and test the stethoscopes in question. The data at hand shows that higher-end stethoscopes offered superior sound quality and enabled accurate diagnoses more often. Detecting hyperdynamic bowel sounds stood out as an exception. All volunteers but five using brand 1, four using brand 2, and six using brand 3 (about 6% of volunteers) acknowledged the presence of hyperdynamic bowel sounds; however, physicians, as opposed to ICU nurses, did not auscultate long enough to quantify the bowel sounds they picked. We speculate that this is reflective of their daily practice, especially given that the frequency of bowel sounds in adults has little clinical significance.10 The above results were shared with our hospitals’ infection control personnel and administration with the advice to stop using brand 1 as a part of our contact precaution measures.

Multiple previous studies have demonstrated the poor cardiac auscultatory skills among physicians and the inadequate role training programs play in improving these skills.9–14 In our cohort, we tested the most basic auscultatory sounds, namely wheezing, stridor, crackles, systolic murmur, and the presence of bowel sounds. Correct detection rates in our volunteers were modest, with a big room for improvement.

Studies offered the following explanations for this poor performance: easy access to new and more accurate technologies, less focus on physical exam and auscultation skills in medical schools and training programs, and stringent time restraints that shorten the interaction time between physicians and patients.10,12 We wholeheartedly agree with the above rationale, but continue to believe that mastering a set of basic physical exam and auscultation skills is mandatory in making rational and cost-effective decisions regarding further testing.15–17 This set of skills will come in handy in emergent situations and ICU settings in which delays in advanced testing are to be expected. We further believe that this basic set of skills might need to change as new technologies (for example, pocket ultrasound machines) become more available.

To the credit of our resident physicians, their systolic murmur detection rate was about 90%. This detection rate is much higher than previously reported.11–13 Some authors have suggested that changes in prevalence of valvular heart diseases in Western countries made physicians less skillful in identifying them.14 Thirty-three out of our volunteer resident physicians (85%) were international medical graduates from developing countries. Although some literature suggests otherwise, we speculate that examination skills are stressed more commonly in developing counties given the limited resources and the higher prevalence of certain pathologies.18 Despite that, our resident physicians, as those in previous reports, did not demonstrate improvement in their auscultation skills as they progressed through their training.12,13,17

This study has several limitations. First, our data were derived from observations made on a small group of subjects at a single training program, which could limit the generalizability of the results. Second, the study included volunteers only; volunteers are more likely to be interested and motivated individuals. These factors may have contributed to an overestimation of the skills of our health care professionals. Furthermore, using a multiple-choice format might have biased performance positively. Likewise, the improvement in nurses’ performance in identifying the systolic murmur and stridor when tested in the MICU probably resulted from talking to their colleagues who volunteered for the study in the simulation center. Lastly, blinding was not perfect. Despite using sleeping masks and similar earpieces on all three stethoscopes, many volunteers adjusted the stethoscopes in their ears for a better fit. This and the weight of the stethoscope might have given them an idea about the stethoscope being tested. To overcome this, we tested the lowest-end stethoscope first.

In conclusion, the role of stethoscopes as a vector facilitating the spread of MDR bacteria has been well established.18–21 It has become a standard practice to use disposable or patient-dedicated stethoscopes to prevent cross-contamination when caring for patients in contact precautions. Data describing the limitations of these disposable stethoscopes are still scarce.4 In the current study, the accuracy of disposable stethoscopes in the hands of a wide range of health care professionals was compared with other commonly used brands of stethoscopes. Low-end stethoscopes performed poorly, especially in facilitating the diagnosis of stridor and crackles. Furthermore, a clear opportunity for improving basic auscultation skills in our health care professionals continues to exist.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the SimCentral (Amarillo, TX, USA) director and staff for their help.

Author contributions

All authors had access to the data and a role in writing the manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Yokoe DS, Mermel LA, Anderson DJ, et al. A compendium of strategies to prevent health care-associated infections in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(Suppl 1):S12–S21. doi: 10.1086/591060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubberke ER, Gerding DN, Classen D, et al. Strategies to prevent clostridium difficile infections in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(Suppl 1):S81–S92. doi: 10.1086/591065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calfee DP, Salgado CD, Classen D, et al. Strategies to prevent transmission of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(Suppl 1):S62–S80. doi: 10.1086/591061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callahan D, Waugh J, Mathew GA, Granger WM. Stethoscopes: what are we hearing? Biomed Instrum Technol. 2007;41(4):318–323. doi: 10.2345/0899-8205(2007)41[318:SWAWH]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ertel PY, Lawrence M, Song W. How to test stethoscopes. Medical Research Engineering. 1969;8(1):7–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavish B, Heller O. A practical method for evaluating stethoscopes. Biomed Instrum Technol. 1992;26(2):97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abella M, Formolo J, Penney DG. Comparison of the acoustic properties of six popular stethoscopes. J Acoust Soc Am. 1992;91(4 Pt 1):2224–2228. doi: 10.1121/1.403655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durup-Dickenson M, Christensen MK, Gade J. Abdominal auscultation does not provide clear clinical diagnoses. Dan Med J. 2013;60(5):A4620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weitz HH, Mangione S. In defense of the stethoscope and the bedside. Am J Med. 2000;108(8):669–671. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00385-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oddone EZ, Waugh RA, Samsa G, Corey R, Feussner JR. Teaching cardiovascular examination skills: results from a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 1993;95(4):389–396. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90308-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.St Clair EW, Oddone EZ, Waugh RA, Corey GR, Feussner JR. Assessing housestaff diagnostic skills using a cardiology patient simulator. Ann Intern Med. 1992;117(9):751–756. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-117-9-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mangione S. Cardiac auscultatory skills of physicians-in-training: a comparison of three English-speaking countries. Am J Med. 2001;110(3):210–216. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00673-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones JS, Hunt SJ, Carlson SA, Seamon JP. Assessing bedside cardiologic examination skills using “Harvey,” a cardiology patient simulator. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4(10):980–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta S, Michaels AD. Relationship between accurate auscultation of the fourth heart sound and the level of physician experience. Clin Cardiol. 2009;32(2):69–75. doi: 10.1002/clc.20431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneiderman H. Cardiac auscultation and teaching rounds: how can cardiac auscultation be resuscitated? Am J Med. 2001;110(3):233–235. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00736-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lam MZ, Lee TJ, Boey PY, et al. Factors influencing cardiac auscultation proficiency in physician trainees. Singapore Med J. 2005;46(1):11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mangione S, Nieman LZ, Gracely E, Kaye D. The teaching and practice of cardiac auscultation during internal medicine and cardiology training. A nationwide survey. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(1):47–54. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-1-199307010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen HA, Amir J, Matalon A, Mayan R, Beni S, Barzilai A. Stethoscopes and otoscopes – a potential vector of infection? Fam Pract. 1997;14(6):446–449. doi: 10.1093/fampra/14.6.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whittington AM, Whitlow G, Hewson D, Thomas C, Brett SJ. Bacterial contamination of stethoscopes on the intensive care unit. Anaesthesia. 2009;64(6):620–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.05892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merlin MA, Wong ML, Pryor PW, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus on the stethoscopes of emergency medical services providers. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2009;13(1):71–74. doi: 10.1080/10903120802471972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones JS, Hoerle D, Riekse R. Stethoscopes: a potential vector of infection? Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26(3):296–299. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]