Abstract

Purpose

Medical professionals’ practices and knowledge regarding cancer pain management have often been cited as inadequate. This study aimed to evaluate knowledge, practices and perceived barriers regarding cancer pain management among physicians and nurses in Korea.

Methods

A nationwide questionnaire survey was administered to physicians and nurses involved in the care of cancer patients. Questionnaire items covered pain assessment and documentation practices, knowledge regarding cancer pain management, the perceived barriers to cancer pain control, and processes perceived as the major causes of delay in opioid administration.

Results

A total of 333 questionnaires (149 physicians and 284 nurses) were analyzed. Nurses performed pain assessment and documentation more regularly than physicians did. Although physicians had better knowledge of pain management than did nurses, both groups lacked knowledge regarding the side effects and pharmacology of opioids. Physicians working in the palliative care ward and nurses who had received pain management education obtained higher scores on knowledge. Physicians perceived patients’ reluctance to take opioids as a barrier to pain control, more so than did nurses, while nurses perceived patients’ tendency to under-report of pain as a barrier, more so than did physicians. Physicians and nurses held different perceptions regarding major cause of delay during opioid administration.

Conclusions

There were differences between physicians and nurses in knowledge and practices for cancer pain management. An effective educational strategy for cancer pain management is needed in order to improve medical professionals’ knowledge and clinical practices.

Introduction

Pain management is an important aspect in the care of cancer patients. Although cancer pain can be controlled up to 90% of the cases through the use of appropriate methods [1],[2], its prevalence has been reported to be as high as 64% among patients with advanced cancer [3] and pain control was found to be inadequate for more than 40% of patients [4]. Factors relating to the medical professional, patient, and the healthcare system have been identified as causes of this apparent under-treatment of cancer pain among patients [4]. Specifically, medical professionals’ inadequacy in pain assessment and management has been pointed out as an important barrier to cancer pain control [5]–[9].

Studies have noted knowledge deficits in cancer pain management among medical professionals [10],[11]. For example, physicians, especially oncologists, generally have general knowledge of cancer pain management, while seemingly lacking knowledge regarding opioid administration or alternate therapies for pain control [8]. This knowledge deficit typically emerged when physicians calculated opioid dosages for the management of breakthrough pain [12] and when attempting to select the correct response to challenging clinical vignettes [5]. Nurses’ knowledge of opioids as a pain control measure was found to be as inadequate as that of the physicians referred to above [8], demonstrated by their exaggerated fear of the addictive nature of opioids or their potential to culminate in respiratory suppression [6]. In Korea, studies also have reported inadequate knowledge and incorrect attitudes among doctors and nurses [13]–[16]. Kim et al. surveyed 1,204 young doctors from all specialties and determined that the majority of doctors were not knowledgeable about equianalgesic opioid dosages, adjuvant analgesics, the numeric rating scale, and the fact that opioids have no ceiling effect [13].

In Korea, approximately 200,000 people are diagnosed with cancer annually, while more than 70,000 die from the condition [17]. According to another Korean study, 70% of patients with advanced cancer experienced pain, and pain management was inadequate in half of the patients [18].

Cancer pain control forms part of Korea’s national healthcare policy. In order to improve knowledge and practices regarding cancer pain management among medical professionals, Korea’s Ministry of Health and Welfare and the National Cancer Center have been publishing and distributing a national guideline known as the “Cancer Pain Management Guideline” across Korea since 2004. In the current study, we investigated and compared knowledge, practices and perceived barriers regarding cancer pain management among physicians and nurses to identify the need for improvement in clinical practice, education and policy.

Method

Study Design, Participants, And Procedures

This survey took place from September 2010 until June 2011 at 11 hospitals (6 public and 5 private hospitals) across Korea. Doctors and nurses involved in the care of cancer patients were eligible for participation. The research coordinator contacted eligible participants at participating hospitals and subsequently delivered the questionnaires. All participants provided written consent to participate in the study. Upon completion of the questionnaire, participants received a voucher worth 10,000 KRW (approximately US $10) as a reward for their participation. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at 11 participating hospitals (National Cancer Center, Chonbuk National University Hospital, Chonnam National University Hospital, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Chungnam National University Hospital, Pusan National University Hospital, Good Samaritan Hospital, Korea Cancer Center Hospital, Korea University Kuro hospital, KyungHee University Medical Center, The Catholic University of Korea Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital).

Questionnaire Development

The questionnaire was developed by the researchers for the purposes of the current study and pilot-tested and revised by a panel of experts consist of 7 physicians (from specialty of pain, medical oncology, family medicine and preventive medicine) and 8 nurses working in oncology ward or palliative care unit. Questionnaire items relating to knowledge and practices regarding cancer pain management were generated on the basis of the contents of the Cancer Pain Management Guideline published by the Ministry of Health and Welfare and the National Cancer Center. The Guideline encompasses pain assessment, pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic pain management, radiation therapy for pain control, interventional pain management such as nerve block, and approaches towards refractory cancer pain.

Items relating to practices assessed the frequency of pain assessment for admitted patients, specific details of pain assessment, and documentation following assessment. Knowledge of cancer pain management was evaluated through 14 items (11 “true” or “false” questions and 3 multiple choice questions), tapping into the principles of cancer pain management, specific properties of analgesics, interventional pain management, opioid dose calculation, and the duration of re-assessment after opioid administration.

Questions on perceived barriers were extracted from the literature [19]–[23], and comprised 3 categories related to patients, medical staff, and the health care system. The following is an example of an item relating to perceived barriers: “how often does a particular barrier interfere with pain control?” Responses were organized on a 4-point scale, where a scale of 1 indicated “never,” 2 = “sometimes,” 3 = “often,” and 4 = “always.” For each item, frequency of scale 1 and 2 was combined as negative response, and frequency of scale 3 and 4 was combined as positive response for a statistical analysis.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was used to summarize the characteristics of participants and responses to items relating practice, knowledge, and perceived barriers. A chi-squared test was carried out to compare differences between physicians and nurses in terms of practices, knowledge, and perceived barriers to cancer pain control. We used multiple linear regression analysis to determine the relationship between participants’ characteristics and the number of correct responses for knowledge of cancer pain management. β value is a regression coefficient which is interpreted as the difference in the number of correct answers according to the differences in age, sex, whether the participant is working in palliative care unit, and whether the participant had attended any type of cancer pain education. The statistical significance level was set at p<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using the STATA SE version 12.0 software package (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Sample Characteristics

A summary of the study participants’ characteristics is presented in Table 1. A total of 335 questionnaires were collected from 11 hospitals. After excluding 2 incomplete questionnaires, 333 (149 physicians and 284 nurses) questionnaires were included in the final analysis. The participants’ mean age was 33.2 and 29.0 (in years) for physicians and nurses, respectively. 70.8% of participating physicians specialized in internal medicine. 13.3% of physicians and 19.0% of nurses were working in the palliative care ward. More than 70% of physicians and nurses had received cancer pain education.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants.

| Physician, N = 149 | Nurse, N = 284 | |

| Characteristics | n (%) | n (%) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 91 (61.5) | 0 (0) |

| Female | 57 (38.5) | 283 (100) |

| Age (years) Mean (SD) | 33.2 (6.9) | 29.0 (5.8) |

| <40 | 119 (85.6) | 251 (92.9) |

| ≥40 | 20 (14.4) | 19 (7.0) |

| Working experiencein years, Mean (SD) | 7.3 (6.5) | 6.6 (5.8) |

| <10 | 111 (75.5) | 207 (76.7) |

| ≥10 | 36 (24.5) | 63 (23.3) |

| Clinical specialty | ||

| Internal medicine | 104 (70.8) | |

| Surgery | 24 (16.3) | |

| Family medicine | 9 (6.1) | |

| Other* | 10 (6.8) | |

| Working in palliative care unit | 20 (13.3) | 54 (19.0) |

| Having attended any type ofcancer pain education | 106 (72.1) | 232 (78.8) |

*Other includes gynecology, radiation oncology, and odontology.

Pain Assessment Practices And Documentation

Table 2 presents practices relating to pain assessment and documentation among physicians and nurses. Results showed that about three times more nurses indicated that they assessed patients’ pain levels on every round than physicians did (p<0.001). In addition, nurses checked all items relating to pain assessment more frequently than physicians did. Further, a higher proportion of nurses, in comparison to physicians, reported that they documented pain assessment (p<0.001). In additional analysis, there was no significant difference in general characteristics among nurses according to the pain assessment and documentation practices. For physicians, having received cancer pain education and working in the palliative ward were positively associated with doing pain documentation (p = 0.001).

Table 2.

Pain assessment and documentation practices.

| Physician | Nurse | P value | |

| % | % | ||

| Occasion of painassessment | |||

| Every round* | 24.8 | 75.2 | <0.001 |

| On selected occasions* † | 67.1 | 23.2 | <0.001 |

| Seldom* | 4.0 | 0.4 | 0.015 |

| Items checked duringpain assessment | |||

| Location* | 83.8 | 95.8 | <0.001 |

| Quality* | 66.9 | 89.8 | <0.001 |

| Related factor* | 55.4 | 68.8 | 0.006 |

| Severity* | 84.4 | 97.2 | <0.001 |

| Timing* | 69.4 | 78.8 | 0.031 |

| Documentation ofpain assessment* | 60.8 | 98.9 | <0.001 |

*P<0.05.

New admission, when patient complains of pain, or when patient seems to be in pain.

Knowledge Of Cancer Pain Management

The rate of correct responses to each of the questions on knowledge for cancer pain management is shown in Table 3. The mean number of correct responses provided by physicians was higher than that of nurses, at 10.8 and 9.0, respectively. For both physicians and nurses, knowledge deficit was prominent in questions on tolerance for opioid-induced sedation (Question 8: the rate of correct responses was 48.0% and 35.0% for physicians and nurses, respectively) and the duration of re-assessment after intravenous morphine administration (Question 13: 51.0% and 48.4% for physicians and nurses, respectively). The rate of correct responses was higher among physicians for questions on NSAIDs (Question 3), specific properties of opioids and opioid dose calculation (Questions 7, 10, and 12), as well as the utilization of radiotherapy or interventional pain management as measures of pain control (Questions 9 and 11).

Table 3.

Rate of correct responses regarding knowledge of cancer pain management.

| Physician | Nurse | P value | |

| Question | % | % | |

| 1. You should not trust patient’ssubjective reports of pain (F) | 86.5 | 91.3 | 0.118 |

| 2. You should differentiable certain causeof pain which needs specific treatment(i.e. cord compression) (T) | 96.6 | 96.7 | 0.943 |

| 3. Prescribing a few differenttypes of NSAIDs will increasethe analgesic efficacyand decreased adverse effect* (F) | 77.7 | 52.7 | <0.001 |

| 4. Pethidine can be prescribedfor chronic cancer pain safely. (F) | 81.8 | 81.2 | 0.880 |

| 5. Opioid analgesics have ahigh risk of addiction. (F) | 91.9 | 86.3 | 0.087 |

| 6. The effect of immediate releaseoral opioid can be assessed at1 hour after administration (T) | 77.0 | 76.8 | 0.960 |

| 7. Opioid analgesics do not have aceiling effect (T)* | 78.4 | 55.2 | <0.001 |

| 8. Tolerance for opioid-induced sedationdevelops within a few days* (T) | 48.0 | 35.0 | 0.008 |

| 9. For painful bone metastasis,radiotherapy can alleviate the pain or helpto reduce the amount of analgesics* (T) | 82.3 | 53.1 | <0.001 |

| 10. Opioid-induced respiratorysuppression is common* (F) | 82.4 | 54.9 | <0.001 |

| 11. Celiac plexus block is effective fortreating cancer pain at upper abdomen.* (T) | 68.5 | 45.3 | <0.001 |

| 12. Calculation of opioid rescue dose* | 73.1 | 52.4 | <0.001 |

| 13. Duration of evaluation followingintravenous morphine administration | 51.0 | 48.4 | 0.607 |

| 14. Knowledge regardingrefractory cancer pain | 96.0 | 93.6 | 0.314 |

| Mean number of correctresponses*, Mean (SD) | 10.8 (2.4) | 9.0 (2.5) | <0.001 |

*P<0.05.

A relationship between the number of correct responses given on knowledge of cancer pain management and the sample characteristics is shown in Table 4. Working in palliative care unit was associated with a higher number of correct responses for physicians. For nurses, being older and having received cancer pain education were related to a higher rate of correct responses.

Table 4.

Relationship between knowledge and characteristics of participants.

| Physician | Nurse | |

| β (95% CI) | β (95% CI) | |

| Age | NS | 0.07 (0.02, 0.12) |

| Sex* | NS | - |

| Working in palliative care unit† | 1.25 (0.05, 2.44) | NS |

| Having attended any type of cancer pain education‡ | NS | 1.75 (0.95, 2.56) |

Multiple linear regression analysis for the number of correct answers for knowledge with general characteristics of participants as independent variables.

β regression coefficient; NS not significant.

Reference values: *Male; †Not working in the palliative care ward; ‡Not having attended any type of cancer pain education.

Perceived Barriers For Cancer Pain Management

Perceived barriers for cancer pain control were compared; results are described in Table 5. Time constraints and insufficient knowledge of pain control were cited by both nurses and physicians as barriers to cancer pain management that were experienced more frequently than other barriers. Physicians perceived barriers such as the “patient’s reluctance to take opioids” (p = 0.011) and “not prioritizing pain control” (p = 0.003) to a higher extent than nurses. In contrast, nurses perceived “insufficient communication with patients” (p = 0.001) and “patients’ reluctance to report pain” (p = 0.030) as barriers to a higher extent than physicians.

Table 5.

Perceived barriers to cancer pain control.

| Physician | Nurse | P value | |

| % | % | ||

| Related to medical staff | |||

| Inadequate pain assessment | 37.6 | 36.8 | 0.864 |

| Inadequate experienceon pain control | 42.3 | 35.7 | 0.180 |

| Insufficient knowledgeof pain control | 45.0 | 40.8 | 0.403 |

| Time constraints* | 75.8 | 66.1 | 0.036 |

| Reluctance to prescribeopioid | 23.5 | 25.8 | 0.599 |

| Insufficient communicationwith patient* | 30.2 | 47.0 | 0.001 |

| Patient-related | |||

| Reluctance to report pain* | 36.1 | 47.0 | 0.030 |

| Reluctance to take opioid* | 54.1 | 41.1 | 0.011 |

| Insufficient communicationwith medical staff | 44.6 | 49.1 | 0.373 |

| Financial constraints | 12.8 | 13.3 | 0.891 |

| Insufficient knowledge ofpain control | 60.5 | 57.7 | 0.572 |

| Related to the health care system | |||

| Strict regulation of opioids | 29.1 | 36.5 | 0.120 |

| Inadequate staffing | 41.9 | 39.7 | 0.662 |

| Limited stock of differenttypes of opioids | 29.1 | 27.1 | 0.675 |

| Cancer pain management is notconsidered as important* | 43.5 | 29.3 | 0.003 |

| Medication and intervention costs* | 32.7 | 23.6 | 0.044 |

*P<0.05.

Perceptions Regarding Processes Delaying Opioid Administration

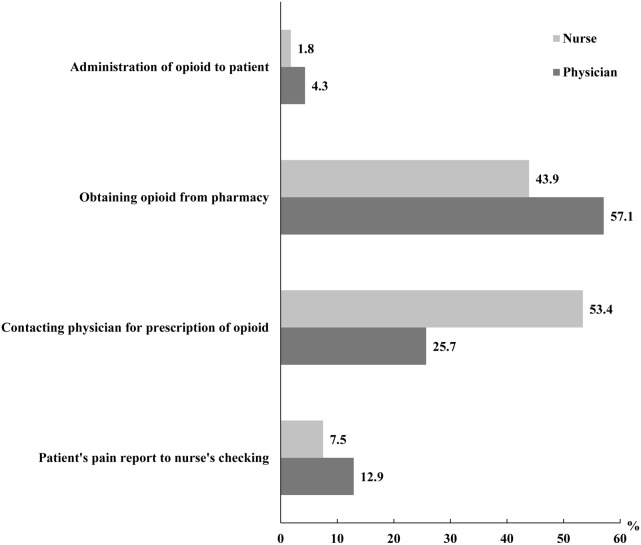

Figure 1 depicts differences in perceptions regarding processes considered to be major sources of delay in the administration of opioids between physicians and nurses. In this regard, “obtaining opioids from pharmacy” was cited by 57.1% of physicians, while 53.4% of nurses cited “contacting physician for prescription of opioid” (p<0.001).

Figure 1. The most delayed process during opioid administration perceived by physicians and nurses.

Discussion

This is the first nationwide study to evaluate knowledge and practices relating to cancer pain management among doctors and nurses in Korea, on the basis of the national Cancer Pain Management Guideline. Overall, results showed that doctors have better knowledge of cancer pain management than nurses, while the latter tended to conduct regular pain assessment and documentation practice more frequently. In addition, doctors and nurses held different perceptions regarding barriers to cancer pain management and the opioid administration process.

The differences found between nurses and doctors in knowledge and practices reflect areas requiring improvement in cancer pain management within these professions. Similarly to results from previous studies [10],[24],[25], our findings showed that doctors scored higher on knowledge than nurses. In our study, both doctors and nurses displayed substantial knowledge deficits regarding tolerance for opioid-induced sedation, the duration of evaluation after opioid administration, calculation of rescue opioid dosages, and utilization of other modalities, such as celiac plexus block. This result is also consistent with findings from previous studies [5],[8],[12]. The low rate of correct responses obtained for knowledge regarding celiac plexus block indicates limited understanding of specialist areas within the medical field, which could lead to less referrals to other specialists. It was reported in a previous study that less than 20% of oncologists referred their patients to palliative or pain specialists [5]. Moreover, medical staff with insufficient knowledge of pain control may delay the administration of opioids to patients [15].

It is generally agreed that the education of medical professionals is necessary to improve cancer pain management. Findings from our study showed that having received cancer pain education was significantly associated with better knowledge among nurses, which was compatible with findings from other study [26]. However, this benefit of education is unclear among physicians. In our finding, knowledge regarding cancer pain management was not significantly different between physicians who received cancer pain education and who didn’t. This echoes with previous study [5] which showed increased continued medical education for pain management could not satisfy the clinical need in pain management. In comparison, projects based approaches which utilized developing action plan [27] or continued quality improvement [28] for pain management reported improved practice and knowledge among medical professionals. This suggests that delivering knowledge alone is not enough to promote cancer pain management, and additional educational strategy such as combining different education methods is needed [29]. For example, the didactic lecture is used for delivering general principles, while small group discussions are more suitable for discussions of clinical cases [29]. This issue relating to educational methods seems to be applicable to the Korean context, where didactic lectures are most widely used for medical education.

In the current study, nurses practiced pain assessment and documentation more regularly than physicians. This is compatible with findings from a previous study which reported that nurses were more skilled at pain assessment, as compared to doctors or pharmacists [8]. This difference could be explained by the roll allocation between nurses and physicians, since nurses are usually required to monitor and report patient’s symptom to physicians. Another consideration which could have influenced nurses’ pain assessment and documentation practice in our survey is the institutional accreditation standard. In this regard, all but one participating hospitals in the current study were accredited by Korea Institute for Healthcare Accreditation (KOIHA), which recommends to assess pain using assessment tool for inpatients.

Time constraints and insufficient knowledge regarding pain management of medical professional were the most commonly encountered barriers to effective pain management for both physicians and nurses. Interestingly, physicians and nurses held different perceptions regarding patient-related barriers. Physicians perceived the “patient’s reluctance to take opioid” as a barrier more often, while nurses perceived the “patient underreporting pain” more often. This is comparable to findings from a previous study, wherein doctors tended to believe that patients over-reported their pain, more so than nurses [8].

There were differences between the nurses and the physicians in perceptions regarding factors that contributed the most towards the delay in the opioid administration process. This discordance of perception between physicians and nurses seems to reflect insufficient coordination of the opioid administration process. For example, in many hospital wards in Korea, nurses are often required to confirm the administration of opioids with physicians, even when there is an “as needed” opioid prescription for breakthrough pain. Moreover, opioids are usually kept in hospital pharmacies, rather than wards, due to the strict regulation policy. In such instances, traveling between the pharmacy and the ward to obtain opioids is time-consuming. In order to reduce the duration of this process, there is a need for institutional policy change, which could advocate the storage of opioids in hospital wards as well as clear team communication about executing standing order for breakthrough pain.

This study has a few limitations. First, although we performed a multicenter study, the results may not represent practices and knowledge of all medical professionals in Korea. Second, in order to accurately measure actual pain assessment and documentation practices, additional monitoring, such as auditing charts, is needed. Third, in this study, we simply asked whether participants had attended pain education before, so as to determine exposure to the educational experience, without considering the level of such exposure. However, the content and methods used in cancer pain management education could be diverse; this, however, was not considered in the current study. Finally, the actual duration of the each process for the administration of opioid was not measured. Therefore we couldn’t verify the medical professional’s perception for the delayed process.

In conclusion, physicians showed better knowledge of cancer pain management, while nurses performed better in pain assessment and documentation practices. Although time constraints were perceived more frequently as a barrier to cancer pain management, physicians perceived patients’ reluctance to take opioids as a barrier, more so than nurses, while nurses deemed patients’ underreporting of pain as a barrier to pain control, more so than physicians. The findings in this study indicate that changes in the educational strategy are required to enhance clinical practice among healthcare professionals in relation to cancer pain management.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the participation of the 11 institutions below.

National Cancer Center, Chonbuk National University Hospital, Chonnam National University Hospital, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Chungnam National University Hospital, Pusan National University Hospital, Good Samaritan Hospital, Korea Cancer Center Hospital, Korea University Kuro hospital, KyungHee University Medical Center, The Catholic University of Korea Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that, for approved reasons, some access restrictions apply to the data underlying the findings. Our data are available upon request because this study was funded by National Cancer Center grant. Thus, the result data from the study belongs to National Cancer Center and the access to data is not permitted without authorization. We will provide the data when there is a request. The contact point is Yeol Kim, the corresponding author.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by National Cancer Center grant number 1032040-1. URL of funder http://ncc.re.kr/english/index.jsp. YK received the funding. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cancer pain relief: with a guide to opioid availability - second edition. (1996) World Health Organization.

- 2. Meuser T, Pietruck C, Radbruch L, Stute P, Lehmann KA, et al. (2001) Symptoms during cancer pain treatment following WHO-guidelines: a longitudinal follow-up study of symptom prevalence, severity and etiology. Pain 93: 247–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Van den Beuken-van Everdingen M, De Rijke J, Kessels A, Schouten H, Van Kleef M, et al. (2007) Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Annals of oncology 18: 1437–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Deandrea S, Montanari M, Moja L, Apolone G (2008) Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Annals of oncology 19: 1985–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Breuer B, Fleishman SB, Cruciani RA, Portenoy RK (2011) Medical oncologists’ attitudes and practice in cancer pain management: A national survey. Journal of Clinical Oncology 29: 4769–4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bernardi M, Catania G, Lambert A, Tridello G, Luzzani M (2007) Knowledge and attitudes about cancer pain management: a national survey of Italian oncology nurses. Eur J Oncol Nurs 11: 272–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sapir R, Catane R, Strauss-Liviatan N, Cherny NI (1999) Cancer pain: knowledge and attitudes of physicians in Israel. Journal of pain and symptom management 17: 266–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xue Y, Schulman-Green D, Czaplinski C, Harris D, McCorkle R (2007) Pain attitudes and knowledge among RNs, pharmacists, and physicians on an inpatient oncology service. Clinical journal of oncology nursing 11: 687–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pargeon KL, Hailey BJ (1999) Barriers to effective cancer pain management: a review of the literature. Journal of pain and symptom management 18: 358–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lebovits AH, Florence I, Bathina R, Hunko V, Fox MT, et al. (1997) Pain knowledge and attitudes of healthcare providers: practice characteristic differences. The Clinical journal of pain 13: 237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yanjun S, Changli W, Ling W, Woo JC, Ai L, et al. (2010) A survey on physician knowledge and attitudes towards clinical use of morphine for cancer pain treatment in China. Supportive Care in Cancer 18: 1455–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gallagher R, Hawley P, Yeomans W (2004) A survey of cancer pain management knowledge and attitudes of British Columbian physicians. Pain research & management: the journal of the Canadian Pain Society = journal de la societe canadienne pour le traitement de la douleur 9: 188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim M-H, Park H, Park EC, Park K (2011) Attitude and knowledge of physicians about cancer pain management: young doctors of South Korea in their early career. Japanese journal of clinical oncology 41: 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim HJ, Park IS, Kang KJ (2012) Knowledge and Awareness of Nurses and Doctors Regarding Cancer Pain Management in a Tertiary Hospital. Asian Oncol Nurs 12: 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jun M-H, Park K-S, Gong S-H, Lee S-H, Kim Y-H, et al. (2006) Knowledge and Attitude toward Cancer Pain Management: Clinical Nurses Versus Doctors. Korean Acad Soc Nurs Edu 12: 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park H, Koh MJ, Lee HS, Kim YM, Kim MS (2003) Nurses’ knowledge about and attitude toward cancer pain management: a survey from korean cancer pain management project. Journal of Korean Academy of Adult Nursing 15: 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jung K-W, Won Y-J, Kong H-J, Oh C-M, Seo HG, et al. (2013) Cancer Statistics in Korea: Incidence, Mortality, Survival and Prevalence in 2010. Cancer Res Treat 45: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yun YH, Heo DS, Lee IG, Jeong HS, Kim HJ, et al. (2003) Multicenter Study of Pain and Its Management in Patients with Advanced Cancer in Korea. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 25: 430–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gunnarsdottir S, Donovan HS, Serlin RC, Voge C, Ward S (2002) Patient-related barriers to pain management: the Barriers Questionnaire II (BQ-II). Pain 99: 385–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jeon YS, Kim HK, Cleeland CS, Wang XS (2007) Clinicians’ practice and attitudes toward cancer pain management in Korea. Support Care Cancer 15: 463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ger L-P, Ho S-T, Wang J-J (2000) Physicians’ knowledge and attitudes toward the use of analgesics for cancer pain management: a survey of two medical centers in Taiwan. Journal of Pain and Symptom management 20: 335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun VC, Borneman T, Ferrell B, Piper B, Koczywas M, et al. (2007) Overcoming barriers to cancer pain management: an institutional change model. J Pain Symptom Manage 34: 359–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.International Associations for the Study of Pain. (2008) Barriers to Cancer Pain Treatment; Cancer Pain Fact Sheet.

- 24. Furstenberg CT, Ahles TA, Whedon MB, Pierce KL, Dolan M, et al. (1998) Knowledge and attitudes of health-care providers toward cancer pain management: a comparison of physicians, nurses, and pharmacists in the state of New Hampshire. Journal of pain and symptom management 15: 335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Visentin M, Trentin L, de Marco R, Zanolin E (2001) Knowledge and attitudes of Italian medical staff towards the approach and treatment of patients in pain. Journal of pain and symptom management 22: 925–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lui LYY, So WKW, Fong DYT (2008) Knowledge and attitudes regarding pain management among nurses in Hong Kong medical units. Journal of Clinical Nursing 17: 2014–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Weissman DE, Dahl JL (1995) Update on the cancer pain role model education program. Journal of pain and symptom management 10: 292–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bookbinder M, Covle N, Kiss M, Goldstein ML, Holritz K, et al. (1996) Implementing national standards for cancer pain management: program model and evaluation. Journal of pain and symptom management 12: 334–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weissman DE (1996) Cancer pain education for physicians in practice: Establishing a new paradigm. Journal of pain and symptom management 12: 364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that, for approved reasons, some access restrictions apply to the data underlying the findings. Our data are available upon request because this study was funded by National Cancer Center grant. Thus, the result data from the study belongs to National Cancer Center and the access to data is not permitted without authorization. We will provide the data when there is a request. The contact point is Yeol Kim, the corresponding author.