Background: The mechanism and players involved in centriole duplication process are not fully understood.

Results: Centrobin and centrosomal protein 4.1-associated-protein (CPAP) interact. Depletion of centrobin results in the disappearance of CPAP from centrioles and inhibition of centriole elongation.

Conclusion: Centrobin-CPAP interaction promotes centriolar CPAP localization for centriole duplication.

Significance: Identifying the key molecular events is crucial for understanding the centriole duplication process.

Keywords: Centriole, Centrosome, Cloning, Confocal Microscopy, Gene Expression, CEP152, CPAP, Centrobin

Abstract

Centriole duplication is the process by which two new daughter centrioles are generated from the proximal end of preexisting mother centrioles. Accurate centriole duplication is important for many cellular and physiological events, including cell division and ciliogenesis. Centrosomal protein 4.1-associated protein (CPAP), centrosomal protein of 152 kDa (CEP152), and centrobin are known to be essential for centriole duplication. However, the precise mechanism by which they contribute to centriole duplication is not known. In this study, we show that centrobin interacts with CEP152 and CPAP, and the centrobin-CPAP interaction is critical for centriole duplication. Although depletion of centrobin from cells did not have an effect on the centriolar levels of CEP152, it caused the disappearance of CPAP from both the preexisting and newly formed centrioles. Moreover, exogenous expression of the CPAP-binding fragment of centrobin also caused the disappearance of CPAP from both the preexisting and newly synthesized centrioles, possibly in a dominant negative manner, thereby inhibiting centriole duplication and the PLK4 overexpression-mediated centrosome amplification. Interestingly, exogenous overexpression of CPAP in the centrobin-depleted cells did not restore CPAP localization to the centrioles. However, restoration of centrobin expression in the centrobin-depleted cells led to the reappearance of centriolar CPAP. Hence, we conclude that centrobin-CPAP interaction is critical for the recruitment of CPAP to procentrioles to promote the elongation of daughter centrioles and for the persistence of CPAP on preexisting mother centrioles. Our study indicates that regulation of CPAP levels on the centrioles by centrobin is critical for preserving the normal size, shape, and number of centrioles in the cell.

Introduction

Centrosomes are microtubule-organizing centers of the animal cell that are important for normal cell division (1–3). Centrosomes have an essential role during ciliogenesis as well as spindle positioning at mitosis (4, 5). Centriole duplication is tightly coordinated with the DNA duplication process, and both events initiate when the cell transitions to S phase (6–9). Abnormalities in centriolar duplication have been linked to tumorigenesis, genetic instability, and ciliopathies. In particular, brain development disorders, such as microcephaly and Seckel syndrome, have been linked to mutations in genes encoding centriole proteins and uncontrolled centriole duplication. Centrosome amplification and accumulation of aneuploid cells in these disorders results in depletion of neural stem cells and affects brain development (4, 10–13).

The centrosome consists of two orthogonally arranged, barrel-shaped centrioles (14–16). The two centrioles of each centrosome are morphologically different and are designated as the mother and daughter centrioles, based on the presence of distal and subdistal appendages that are found only on the mother centriole (15, 17). In mammalian cells, the centrioles are ∼500 μm in length and ∼200 μm in diameter and have nine sets of microtubule triplets that are composed of αβ-tubulin heterodimers (18–21). During centriole biogenesis, new daughter centrioles are assembled from the proximal end of preexisting centrioles (22, 23). Regulation of the number, size, shape, and position of centrioles in the cell depends on optimum expression levels as well as the order in which individual centriolar proteins get positioned on the mother centrioles during the duplication process.

More than 200 centriolar proteins have been identified (24), and some of the critical duplication-associated proteins in humans are centrobin, CEP192, CEP152, PLK4, hSAS-6, CPAP,2 STIL, CP110, CEP135, and α-tubulin (25–32). Based on electron microscopy studies, the centriole duplication process can be broadly divided into initiation, elongation, and maturation stages. Whereas overexpression of PLK4 and CEP152 de novo initiated centriole biogenesis and amplified the centrioles (25, 27, 30), depletion of CPAP in this model inhibited the amplification of centrioles (30). CPAP overexpression, on the other hand, resulted in de novo elongation of centrioles beyond their predetermined length of 0.5 μm (29, 33, 34). Previously, mutations in CPAP as well as the CEP152 gene have been linked to microcephaly and Seckel syndrome (13, 35, 36). Interestingly, abrogation of the CPAP gene in a mouse model also resulted in abnormal centriole numbers as well as microcephaly (37). Hence, CPAP has a crucial role in regulating centriole biogenesis, and understanding the associated molecular mechanism would unravel the role of centriole duplication in a number of important physiological processes. Recently, it was demonstrated that interaction of CEP152 with PLK4 and CPAP facilitates the centriolar recruitment of latter proteins (25, 38, 39). These studies indicated that both CEP152 and CPAP are essential centriole duplication proteins that are recruited to the biogenesis site at a very early stage (40, 41), and attempts to identify their interacting partners will reveal the key events of the centriole biogenesis process.

We and others have shown that centrobin is essential for centriole duplication (41–43). Sequential phosphorylation of centrobin by the kinases NEK2 and PLK1 stabilizes the microtubules (44). Centrobin also has an essential role in the formation of functional mitotic spindles (45). In Drosophila, centrobin was reported to be crucial for defining asymmetry during neuroblast division (46). These reports show that centrobin has a critical role in centriole duplication and other cellular events leading to cell division.

Here, we show that the human centrobin interacts with both CEP152 and CPAP. In centrobin-depleted cells, CEP152 localization to the centrioles was not affected; however, in CEP152-depleted cells, the centriolar localization of centrobin and CPAP was inhibited. Intriguingly, exogenous expression of the CEP152-binding fragment of centrobin, which lacks the necessary centriole translocation sequences, did not affect the recruitment of CEP152 to the centrioles and instead caused disappearance of CPAP from both the newly formed daughter and preexisting mother centrioles. Further studies have revealed a direct interaction between centrobin and CPAP, and this interaction is critical for centriole biogenesis. These studies indicate that CPAP functions downstream of centrobin in the centriole biogenesis pathway. The interaction between centrobin and CPAP is therefore crucial not only for the centriolar localization of CPAP but also for the persistence of CPAP on them for normal centriole biogenesis and integrity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines and Media

293T, HeLa, and U2OS cells were grown in DMEM (Cellgro, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, sodium pyruvate, minimum essential amino acids, and antibiotic-antimycotic solutions. Plasmid transfections were done using the calcium phosphate method, and siRNAs were transfected using Oligofectamine reagent (Invitrogen). U2OS cells with inducible expression of GFP CPAP have been described before (29, 41).

Antibodies and Reagents

Anti-centrobin monoclonal antibody has been described previously (41). The polyclonal anti-GFP antibody, used for immunoblotting (IB), was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., and the monoclonal anti-GFP antibody, used for immunoprecipitation (IP), was purchased from Invitrogen. The polyclonal antibodies for CPAP were kindly provided by Dr. Gonczy (Swiss Institute, Lausanne, Switzerland) and Dr. Tang (Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Taipei, Taiwan) or purchased from Proteintech, Inc. The CEP152 polyclonal antibody was purchased from Bethyl Labs. RNAi-mediated depletion of proteins was performed using siRNA duplexes purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The sequences for the siRNA against CEP152 and centrobin have been reported before (39, 42). The Alexa Fluor 488/568/647-linked secondary antibodies as well as the α tubulin-Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate were purchased from Invitrogen. Hydroxyurea was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The nickel and glutathione beads were procured from GE Healthcare.

Plasmid Constructs

The cloning of centrobin(1–903) into EGFP-N1 and pET28a vectors has been described previously (42). Briefly, the Myc-centrobin vector was constructed by replacing the CMV promoter of EGFP vector with the endogenous centrobin promoter to overcome the high level expression-mediated aggregation of centrobin protein as reported earlier (41, 42, 47). To enhance detectability, 16 Myc tags were added to the C terminus of the protein using XhoI and SalI restriction enzymes. EGFPN1(1–364), -(1–182), and -(183–364) fragments of centrobin were generated by cloning PCR products under the XhoI and SacII restriction enzymes. The GST-CPAP constructs spanning residues 1–996 and 970–1338 were kindly provided by Dr. Kunsoo Rhee (Seoul National University). The EGFP-C1-CPAP and mCherry-PLK4 constructs were kindly provided by Dr. Tang. The EGFP-C1-CEP152 construct was kindly provided by Dr. Ingrid Hoffman (German Cancer Research Center). The GFP-Daam1-expressing construct was a kind gift from Dr. Puligilla (Medical University of South Carolina), whereas the Myc-GRP78-expressing construct was obtained from Addgene, Inc.

Mass Spectrometry Protocol

The GST-tagged fragment of centrobin spanning aa 1–364 was expressed in bacteria, purified using glutathione beads, and incubated with rat testes lysate, and the bound proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, followed by Coomassie Blue staining. Unique bands, as compared with the control glutathione beads, were washed and in-gel digested overnight with trypsin. The peptides were extracted, desalted, concentrated, and analyzed by reverse phase nano-LC-MS/MS on a Finnigan LTQ mass spectrometer using a 1-h gradient and data-dependent MS/MS collection. These raw data were then searched against the Swiss-Prot database with assumptions for trypsin using the ThermoFinnigan TurboSequest software. Services for mass spectrometry were provided by CTL Bio (Rockville, MD).

Immunofluorescence

For visualization of centrioles, cells grown on coverslips were left on ice for 0.5 h, followed by treatment with an extraction buffer (20 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 50 mm NaCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 300 mm sucrose, and 0.5% Triton X-100) and fixed with ice-cold methanol at −20 °C. The cells were then incubated with appropriate primary antibodies diluted in PBS containing 0.02% Tween 20 and then incubated with Alexa Fluor 488/568/647-linked secondary antibodies, followed by DAPI staining for 10 min. Coverslips were placed on slides in mounting medium containing antifade (Invitrogen), and imaging was conducted at room temperature. Images were acquired using either the Olympus FV10i, which has an automated scanning confocal system and is equipped with a ×60 water immersion objective 1.345 numerical aperture or the Zeiss 510 Meta confocal microscope with a ×60 oil immersion objective having a 1.4 numerical aperture.

Immunoprecipitation

For binding assays, cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. The cells were washed in ice-cold PBS 48 h after transfection and then lysed using IP lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, and 100 mm PMSF) for 40 min on ice. The DNA was sheared using a 21-gauge needle, after which lysates were spun at 14,000 rpm for 20 min. Lysates were precleared with a 50% slurry of protein A/G beads (Pierce), followed by incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and then with protein A/G beads for 1 h at 4 °C to precipitate the immune complexes. After washing six times using lysis buffer, the bound proteins were fractionated on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and Western blotting was performed to detect the bound proteins. For IP, 5 μg of anti-GFP antibody was used per ml of lysate.

In Vitro Binding

Purified proteins were prepared by standard protocol using the BL21 strain of Escherichia coli and IPTG (Sigma-Aldrich) as the inducing agent. For the purification of His-centrobin(1–903), His-GAD65, and GST-CPAP fragments, 2 m urea was added to the lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 1% Nonidet P-40, and 100 mm PMSF). After induction, bacteria were pelleted and frozen overnight at −80 °C, after which they were sonicated in the lysis buffer. Glutathione or nickel beads (GE Healthcare) were added to lysates to concentrate the proteins. Protein purity and content were tested by SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining of the gel, after which equal amounts were used for in vitro binding. Binding was performed for 2 h at 4 °C. Protein-bound nickel or glutathione beads were washed six times, after which they were treated with SDS sample buffer for further analysis.

Centriole Duplication Assay

U2OS cells were pretreated with 16 mm hydroxyurea (HU) for 8 h, after which they were transfected with the indicated plasmids for a total of 96 h. The transfected cells were then immunostained with the indicated antibodies.

Centriole Initiation Assay

U2OS cells were transfected with control or centrobin mutants, followed by high speed flow sorting of the GFP-positive cells after 2 days of transfection. To study initiation, cells were then retransfected with the mCherry-PLK4 construct for another 2 days. Cells were treated with HU to arrest cells in S phase. Rosette-like structures formed upon PLK4 overexpression were identified by staining with anti-centrin and -centrobin antibodies and Alexa-488- or Alexa-647-linked secondary antibodies.

Centriole Elongation Assay

U2OS cells inducibly expressing GFP-tagged CPAP were used for the elongation assay and have been described before (41).

RNAi

To assess the effect of depletion of centrobin and CEP152 on their centriolar recruitment, HeLa cells were grown on coverslips and transfected with control or centrobin/CEP152 RNAi for 48 h, followed by treatment with HU for another 16 h.

Flow Sorting

Small molecular weight proteins, such as GFP centrobin-CBD and control GFP, get extracted upon fixation with methanol, making it impossible to identify the transfected cells. Hence, GFP-positive cells were subjected to high speed cell sorting using the MoFlo AstriosTM cell sorter prior to fixation for immunofluorescence analysis as specified.

Statistics

At least 100 cells were counted for every sample in each experiment. Data presented are an average of three experiments, and S.D. was plotted. The p values were calculated employing Student's t test.

RESULTS

Centrobin Interacts with CEP152

To identify the proteins that interact with centrobin, a GST-tagged fragment of centrobin spanning aa 1–364 was expressed in bacteria, purified using glutathione beads, and incubated with rat testes lysate, and the bound proteins were subjected to mass spectrometric analysis. This experiment identified CEP152 as a centrobin-interacting protein (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Identification of CEP152 peptides in centrobin-protein complex by mass spectrometry

| Spectrum number assigned by the mass spectrometer | Peptide sequence of CEP152 (protein accession no. O94986) | MH+a | zb | XCc score | ΔCnd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1731 | NLDATVTALK | 1045.590 | 2 | 2.45 | 0.42 |

| 3666 | QMVQDFDHDKQEAVDR | 1960.880 | 2 | 3.79 | 0.19 |

a Deprotonated molecular ions.

b Charge state observed for each peptide.

c Cross-correlation values.

d Fractional difference between the XC value and the next highest possible hit XC value.

CEP152 is one of the earliest proteins in centriole biogenesis and is essential for centriole duplication (40). Therefore, centrobin-CEP152 interaction was examined using lysates of Myc-centrobin and GFP-CEP152-cotransfected 293T cells. Plasmids expressing non-centriolar proteins, GFP-Daam1 and Myc-GRP78, were co-transfected with Myc-centrobin and GFP-CEP152, respectively, as controls to determine the specificity of centrobin-CEP152 interaction. Anti-GFP antibody co-precipitated Myc-centrobin, but not Myc-GRP78, along with GFP-CEP152 from the 293T cell lysates (Fig. 1A). In addition, anti-GFP antibody did not co-precipitate centrobin with Daam1 from cells that express GFP-Daam1 and Myc-centrobin, suggesting that the centrobin-CEP152 interaction is specific.

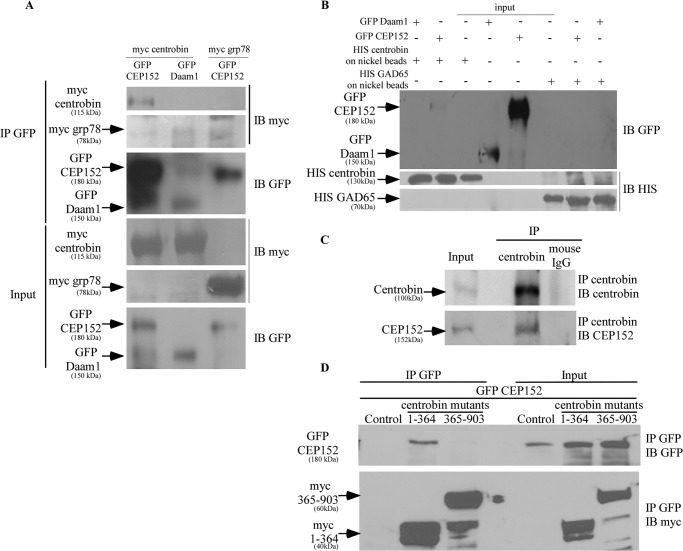

FIGURE 1.

Centrobin binds to CEP152 in vivo and in vitro via its C-terminal 364 aa. A, lysates of 293T cells transfected with Myc-centrobin or Myc-GRP78 and GFP-CEP152 or GFP-Daam1 expression vectors were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-GFP antibody. Immunoblotting was done with anti-Myc and -GFP antibodies. B, His-centrobin and His-GAD65 was purified from IPTG-induced E. coli BL21 bacteria using nickel beads. These nickel beads were then incubated with lysates of 293T cells expressing GFP-CEP152 or GFP-Daam1. Immunoblotting was performed using anti-GFP and anti-His antibodies. C, endogenous centrobin was immunoprecipitated from lysates of 293T cells using the anti-centrobin monoclonal antibody, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. D, 293T cells were co-transfected with control or GFP-CEP152 and Myc-centrobin fragment 1–364 or 365–903 expression vectors. Immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-GFP antibody, and immunoblotting was done using anti-GFP and anti-Myc antibodies.

To further assess the interaction between centrobin and CEP152, His-centrobin and a control protein (His-GAD65) were expressed in bacteria, purified, and used in binding experiments along with lysates from GFP-CEP152- or GFP-Daam-expressing cells. His-centrobin, but not His-GAD65, formed a complex with GFP-CEP152 from 293T cell lysates (Fig. 1B). Further, His-centrobin did not form a complex with the non-centriolar control protein GFP-Daam1, showing the specificity of centrobin-CEP152 interaction. Importantly, IP studies using anti-centrobin antibody demonstrated that the lysates of 293T cells contain endogenous complexes of centrobin and CEP152 (Fig. 1C), confirming the centrobin-CEP152 interaction. To corroborate the mass spectrometric finding of centrobin(1–364) fragment and CEP152 interaction, 293T cells were cotransfected with GFP-CEP152 and Myc-centrobin fragments spanning residues 1–364 or 365–903. IP with the anti-GFP antibody confirmed that the centrobin fragment 1–364, but not 365–903, possesses the CEP152-binding ability (Fig. 1D). These observations confirm the interaction of the N-terminal region of centrobin with CEP152 and suggest a key role for centrobin at the early stages of the centriole duplication process.

Procentriole Localization of Centrobin Is Dependent on CEP152

Because we observed centrobin and CEP152 interaction, the interdependence of centrobin and CEP152 for their recruitment to the procentrioles was examined. HeLa cells were transfected with control, CEP152, or centrobin siRNAs and treated with HU to arrest the cell division at S phase. The depletion efficacy of the transfected siRNAs and the expression levels of relevant proteins were assessed by Western blot (Fig. 2A, left). Cells stained using anti-CEP152, anti-centrobin, and anti-α-tubulin antibodies revealed that whereas centrobin depletion did not affect the centriolar recruitment of CEP152 as compared with control siRNA-transfected cells, centrobin was not localized to the procentrioles in CEP152-depleted cells (Fig. 2A, right). These observations suggest that centrobin functions downstream of CEP152 during centriole biogenesis. In our earlier study, we observed that recruitment of centrobin to the procentrioles was unaltered in CPAP RNAi cells (41). On the other hand, it has been reported that CEP152 depletion blocks CPAP localization to the procentrioles (25, 39). Hence, we assessed the effect of CEP152 depletion on centriolar localization of centrobin and CPAP. HeLa cells that were transfected with control or CEP152 siRNAs were examined for the cellular and centriolar localization of centrobin and CPAP. In agreement with the previous report (25, 39) and our current finding (Fig. 2A), recruitment of CPAP and centrobin to the procentrioles was inhibited upon CEP152 depletion (Fig. 2B, right). The cellular levels of these proteins, however, remained unaffected (Fig. 2B, left). These results suggest that both centrobin and CPAP are recruited to the procentrioles after CEP152.

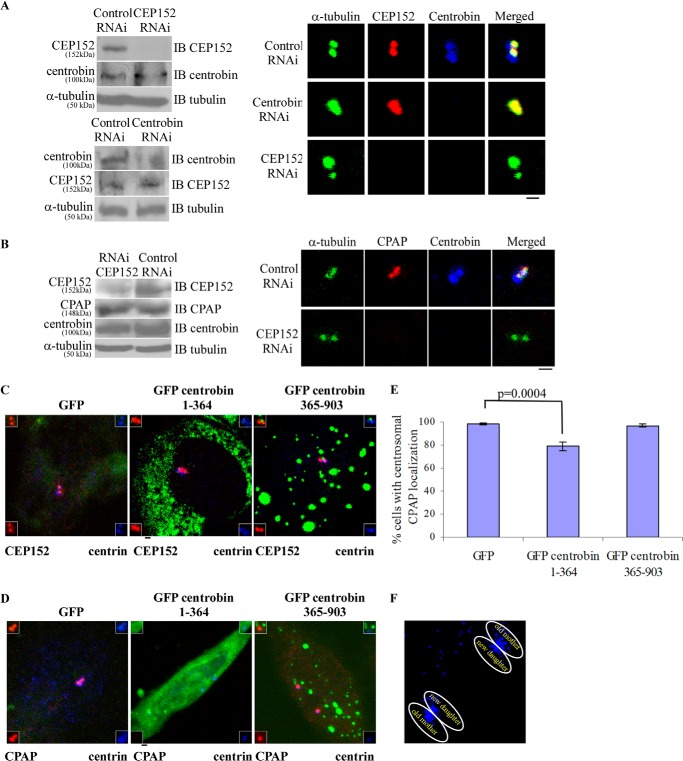

FIGURE 2.

Overexpression of the N-terminal centrobin fragment (aa 1–364) results in loss of CPAP, but not CEP152, from the centrioles. A, HeLa cells transfected with control, centrobin, or CEP152-siRNAs were treated with HU and stained with the anti-centrobin (blue), anti-CEP152 (red), and anti-α-tubulin (green) antibodies. Left, cellular lysate levels of centrobin or CEP152. B, HeLa cells were transfected with control or CEP152 siRNA, treated with HU, and stained with anti-centrobin (blue), anti-CPAP (red), and anti-α-tubulin (green) antibodies. Left, lysates of HeLa cells expressing control or CEP152 siRNA or centrobin siRNA that were tested for cellular levels of centrobin, CEP152, and CPAP. C and D, HeLa cells, pretreated with HU for 8 h, were transfected with GFP or GFP centrobin fragment 1–364 or 365–903. After 4 days, cells were stained with anti-CEP152 (C) or anti-CPAP (D) and anti-centrin antibodies to mark the centrioles. Insets, marked by white boxes, show enlarged centrosomes. Insets at the top left show enlarged centrioles with merged red and green channels, whereas insets at the top right show merged far red and green channels. E, the frequency of cells with CPAP in the centriole in GFP, GFP-centrobin(1–364), and GFP-centrobin(365–903) fragment-expressing cells was examined. 100 cells were counted per group. Each bar represents mean ± S.D. (error bars) of values obtained from three independent experiments, and statistical significance was calculated by Student's t test. Images are maximum intensity projections of Z stacks obtained using an Olympus FV10i confocal microscope. Scale bar, 2 μm. F, enlarged centrioles from the middle image of C are shown to pinpoint different centrioles.

Exogenous Expression of CEP152-binding Fragment of Centrobin Results in the Disappearance of CPAP, but Not CEP152, from the Centrioles

Next, we examined the physiological relevance of the centrobin-CEP152 interaction. HeLa cells were treated with HU, transfected with GFP or GFP-centrobin(1–364) fragment, and immunostained with anti-CEP152 and anti-centrin 3 (to mark the centrioles) antibodies. In addition to GFP-expressing vector, GFP-centrobin(365–903) fragment that possesses the centriolar translocation sequence of centrobin, but does not bind to CEP152, was also included as a control. Centriolar CEP152 levels did not appear to be different between GFP-, centrobin(1–364)-, and centrobin(365–903)-expressing cells (Fig. 2C). However, CPAP, a protein that is known to interact with CEP152 (25, 39), was not detectable on the centrioles in a significant number of centrobin(1–364) fragment-expressing cells (Fig. 2, D and E). Co-staining for the centriolar marker, centrin, suggested that the centrioles in these cells are intact (Fig. 2, D and F). It has been shown that centrin is located at the distal end of centrioles, and the mother (preexisting) centrioles have higher levels of this protein as compared with the newly forming daughter centrioles (procentrioles) (48). In fact, cells expressing centrobin 1–364 fragment clearly show that CPAP is not present on either the procentrioles or preexisting centrioles (Fig. 2, D and F). These data imply that exogenous expression of the N-terminal centrobin(1–364) fragment possibly affects the centriolar CPAP levels in a dominant negative manner and suggest that centrobin interacts with CPAP through this domain.

Centrobin Interacts with CPAP Directly

Next, we examined whether centrobin and CPAP interact in vivo using 293T cells that were cotransfected with GFP-centrobin- and Myc-CPAP-expressing plasmids. IP of lysate from these cells with the anti-GFP antibody revealed that Myc-CPAP co-precipitates with GFP-centrobin (Fig. 3A), suggesting that centrobin interacts with CPAP. As observed with CEP152 in Fig. 1A, GFP-Daam1 and Myc-GRP78 that were used as controls did not co-precipitate with Myc-centrobin and GFP-CPAP, respectively, indicating that the observed binding between centrobin and CPAP is indeed specific. To confirm centrobin-CPAP binding, His-centrobin and His-GAD65 were expressed in bacteria, purified using nickel beads, and incubated with GFP-CPAP-expressing 293T cell lysates. GFP-Daam1-expressing cell lysate and His-GAD65 on nickel beads were also used as controls in this experiment. As shown in Fig. 3B, in vitro complex formation was observed only between centrobin and CPAP and not between GAD65 and CPAP or centrobin and Daam1, confirming that the centrobin-CPAP interaction is specific. Importantly, immunoprecipitates of 293T cell lysate prepared using the anti-centrobin antibody showed the presence of CPAP in them, suggesting that endogenous complexes of centrobin and CPAP exist (Fig. 3C).

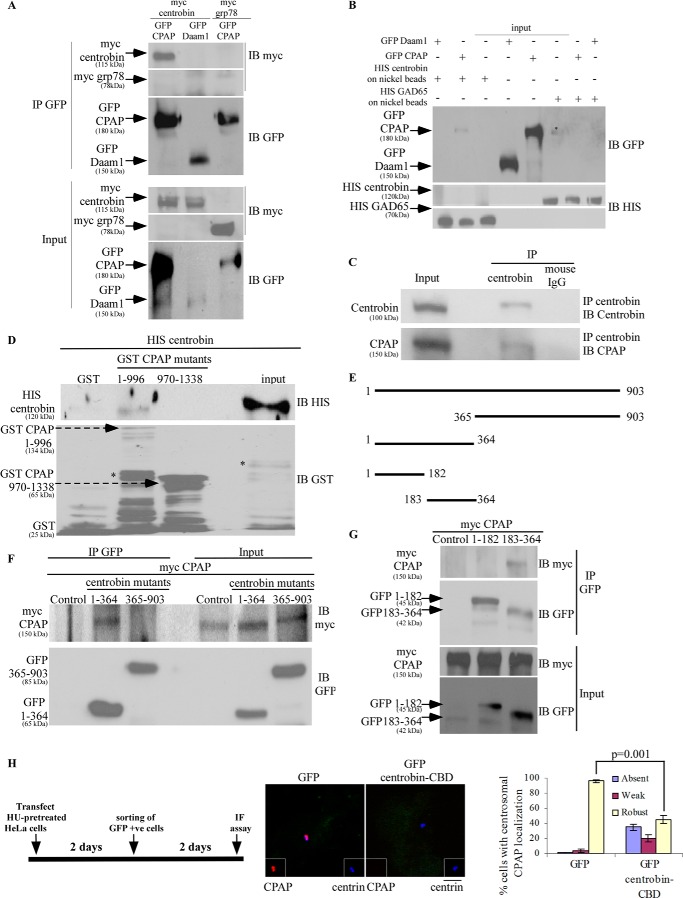

FIGURE 3.

Centrobin interacts with CPAP, and centrobin-CBD expression results in disappearance of CPAP from the centrioles. A, lysates of 293T cells expressing Myc-centrobin or Myc-GRP78 and GFP-CPAP or GFP-Daam1 were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP antibody, and immunoblotting was performed using anti-Myc and anti-GFP antibodies. B, His-centrobin and His-GAD65 were purified from IPTG-induced E. coli BL21 bacteria using nickel beads. These nickel beads were incubated with lysates of 293T cells expressing GFP-CPAP or GFP-Daam1. IB was performed using anti-GFP and anti-His antibodies. C, endogenous centrobin was immunoprecipitated from lysates of 293T cells using the anti-centrobin monoclonal antibody, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. D, His-centrobin, GST, and GST-CPAP fragments spanning residues 1–996 and 970–1338 were purified from IPTG-induced E. coli BL21 bacteria. His-centrobin that was imidazole-eluted off of the beads was incubated with GST or GST-CPAP fragments on the glutathione beads at 4 °C. GST beads were washed and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot. IB was performed with anti-GST and anti-His antibodies. input, 5% imidazole eluted His-centrobin that was used in the binding experiment. E, schematic representation of centrobin fragments generated by deletion mutagenesis to decipher the CPAP binding region. F and G, CPAP binding fragment was identified by cotransfection of 293T cells with Myc-CPAP and control or GFP-centrobin fragment-expressing vectors followed by IP using anti-GFP antibody and IB using anti-GFP and anti-Myc antibodies. H, HU-pretreated HeLa cells were transfected with GFP or GFP(183–364) (centrobin-CBD) vectors as depicted in the left panel, stained with anti-CPAP (red) and anti-centrin (green) antibodies to visualize the centrioles. DAPI (blue) shows nucleus (middle). The bar diagram shows the percentage of cells with detectable levels of CPAP in centrioles (right). Error bars, S.D. Asterisks (B and D), nonspecific bands. IF, immunofluorescence.

We then examined if centrobin and CPAP interact directly. His-centrobin and GST-CPAP fragments, spanning aa residues 1–996 and 970–1338, were expressed in bacteria and purified using nickel and glutathione beads, respectively. Beads carrying GST alone or GST-CPAP fragments were incubated with purified His-centrobin and subjected to IB using anti-His antibody. Fig. 3D shows that the GST-CPAP(1–996) fragment, but not GST or GST-CPAP(970–1338) fragment, binds to His-centrobin. This result obtained using proteins expressed in bacteria shows that centrobin and CPAP bind directly, in the absence of any post-translational modifications and other mammalian proteins (Fig. 3D).

CPAP-binding Domain of Centrobin Is Located within Its N-terminal Residues 183–364

To identify the CPAP binding region in centrobin, we generated plasmids with additional centrobin fragments that are shown in the schematic in Fig. 3E. These GFP-centrobin fragments were coexpressed with Myc-CPAP in 293T. IP using the anti-GFP antibody revealed that the CPAP-binding domain of centrobin, similar to CEP152, is located within the N-terminal aa 1–364 region (Fig. 3F) and restricted to residues 183–364 (Fig. 3G). This fragment, hereafter referred to as centrobin-CBD (CPAP-binding domain of centrobin), was used to understand the functional significance of the centrobin-CPAP interaction.

Exogenous Expression of Centrobin-CBD Results in the Loss of CPAP from the Preexisting Centrioles and Procentrioles

Further, we tested the effect of expression of centrobin-CBD on the centriolar CPAP levels in HeLa cells as depicted in the experimental scheme in Fig. 3H (left). HU-treated HeLa cells expressing GFP or GFP-centrobin-CBD were sorted using a high speed cell sorter, followed by staining with anti-CPAP and -centrin antibodies. Whereas 99% of control cells had a robust centriolar CPAP signal, only 55% of centrobin-CBD cells had detectable levels of CPAP on the centrioles (Fig. 3H, middle and right). This finding confirms the effect observed upon expression of centrobin fragment 1–364, indicating that exogenous expression of centrobin-CBD displaced CPAP from both the procentrioles and preexisting centrioles. Our results suggest that centrobin-CBD interferes with the interaction between endogenous centrobin and CPAP in a dominant negative manner and prevents CPAP from localizing to the centrioles. The loss of centriolar CPAP, from both the mother and procentrioles, in centrobin-CBD-expressing cells suggests that the centrobin-CPAP interaction is responsible for maintenance of CPAP levels on the centrioles.

Centrobin-CBD Inhibits Centriole Duplication

Because both centrobin and CPAP are considered essential for centriole duplication (29, 42), we anticipated that depletion of centriolar CPAP by centrobin-CBD, due to dominant negative interference with endogenous centrobin, would cause inhibition of centriole duplication. This notion was tested in U2OS cells that are known to undergo centrosome amplification upon HU treatment (49). HU-treated U2OS cells were transfected with control or GFP-centrobin-CBD vectors and sorted for GFP-positive cells as depicted in the experimental scheme in Fig. 4A. Whereas 70% of control cells had >4 centrioles/cell, indicating centriole amplification, 45% of GFP-centrobin-CBD-expressing cells failed to show >4 centrioles (Fig. 4, B and C). This result shows that the centrobin-CBD fragment expression indeed inhibits centriole duplication, suggesting a critical role for the endogenous centrobin-CPAP interaction in centriole biogenesis.

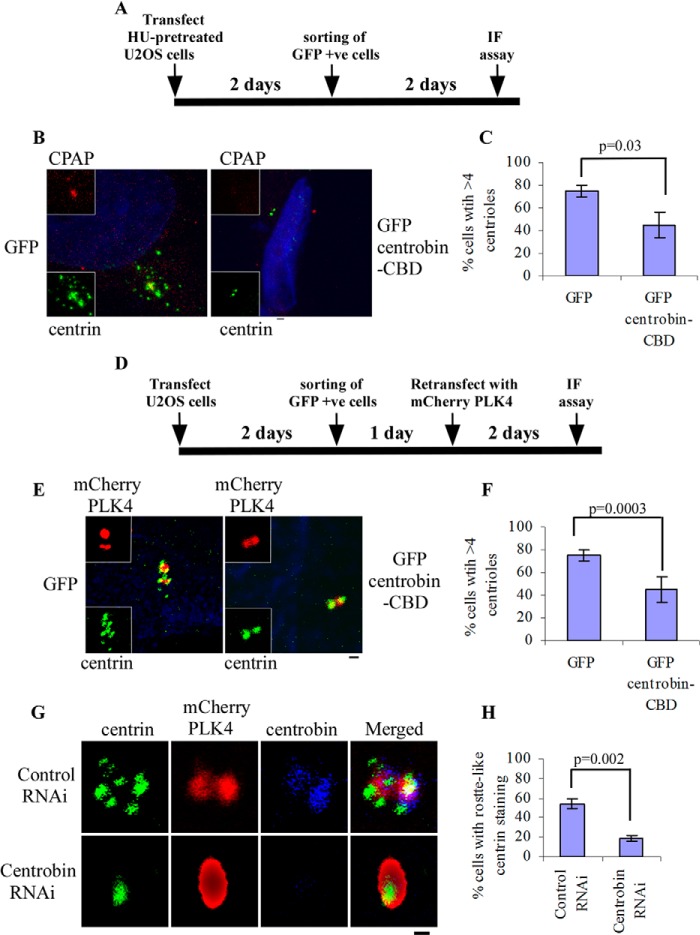

FIGURE 4.

Centrobin-CBD inhibits centriole duplication and PLK4 overexpression-associated centrosome amplification. A, experimental scheme depicting the time line and details for B and C. B, U2OS cells, pretreated with HU for 8 h, were transfected with GFP or GFP centrobin-CBD expression vectors. 96 h after transfection, cells were stained with anti-centrin (green) and anti-CPAP (red) antibodies and DAPI (blue). C, bar diagram shows the percentage of cells with amplified centrioles from B. D, experimental scheme depicting the time line and details for E and F. E, U2OS cells were transfected with GFP or GFP centrobin-CBD expression vectors, followed by retransfection with mCherry PLK4 (red) after 2 days. Cells were stained with anti-centrin (green) antibody and DAPI (blue). F, bar diagram shows the percentage of cells with amplified centrioles from E. G, U2OS cells transfected with control or centrobin siRNA were retransfected with mCherry PLK4 (red) expression vector and stained with anti-centrin (green) and anti-centrobin (blue) antibodies. H, the bar diagram shows the percentage of cells with amplified centrioles from G. Scale bar of the microscopy images, 2 μm. Insets marked by white boxes show enlarged centrosomes. Images in B and C are maximum intensity projections of Z stacks obtained using the Olympus FV10i microscope, whereas E–G show images acquired using the Zeiss 510 Meta microscope. Images were deconvoluted using the Metamorph software. For B, F, and H, 100 cells were counted per group; each bar represents the mean ± S.D. (error bars) of values obtained from three independent experiments; and statistical significance was calculated by Student's t test or two-way analysis of variance.

Centrobin-CBD Inhibits PLK4 Overexpression-associated Centriole Amplification

Overexpression of PLK4 results in de novo amplification of centrioles in U2OS cells. Because this kinase is one of the earliest members of the centriolar protein family to be recruited to the procentrioles, the PLK4-mediated centriole amplification also represents a model for initiation of centriole biogenesis. It has been shown that depletion of CPAP using siRNA inhibits normal centriole biogenesis (29) as well as the PLK4 overexpression-facilitated de novo amplification of centrioles (30). Because centrobin-CBD expression resulted in the disappearance of CPAP from the centrioles, we assessed the effect of this fragment on PLK4 overexpression-associated centriole amplification in U2OS cells. U2OS cells transfected with GFP or GFP-centrobin-CBD were sorted and retransfected with mCherry-PLK4, followed by staining with the anti-centrin antibody to visualize PLK4-mediated rosette-like structure formation (centriole amplification), as depicted in Fig. 4D. Upon quantification, 76% of control cells had the rosette-like centrin distribution as compared with 25% of centrobin-CBD-expressing cells (Fig. 4, E and F). This indicates that centrobin-CBD expression blocks centriole duplication at the initiation stages by interfering with the endogenous centrobin-CPAP interaction.

Depletion of Centrobin Inhibits PLK4 Overexpression-mediated Centriole Amplification

The binding of centrobin with both CEP152 and CPAP as well as the inhibition of PLK4-mediated centriole amplification by centrobin-CBD implies that the recruitment of centrobin to the procentrioles occurs very early in the biogenesis process and may be essential to initiate the duplication process. Therefore, the effect of depletion of endogenous centrobin in this model was tested. U2OS cells were transfected with control or centrobin siRNA and then transfected with mCherry-PLK4, treated with HU, and stained with anti-centrin and anti-centrobin antibodies. Similar to the centrobin-CBD-expressing cells, only 18% of the centrobin RNAi-transfected cells had mCherry-PLK4 overexpression-associated centriole rosette formation as compared with 54% of the control RNAi cells (Fig. 4, G and H). This indicates that in the absence of centrobin, PLK4-mediated de novo initiation of centriole duplication is inhibited.

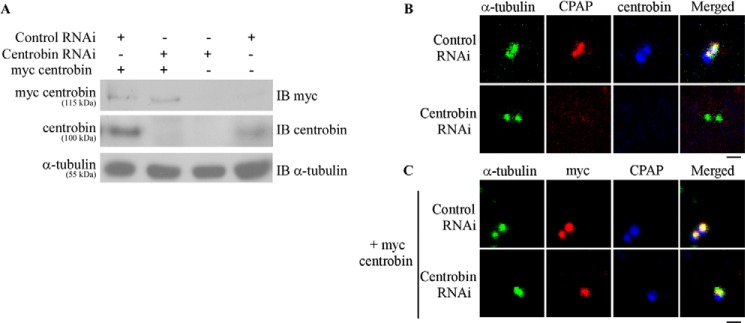

Localization of CPAP on the Centrioles Requires Centrobin

Because exogenous expression of centrobin-CBD resulted in the disappearance of CPAP from the centrioles, we examined whether centrobin depletion also affects the centriolar levels of CPAP. HeLa cells were transfected with control or centrobin siRNA that targets a 3′-untranslated region to deplete the endogenous centrobin (Fig. 5A), treated with HU, and stained with anti-α-tubulin, anti-CPAP, and anti-centrobin antibodies. Although CPAP signals were detected on the centrioles of control siRNA-transfected cells, this protein was not detectable on the centrioles of centrobin-depleted cells. Although the centrioles appear to be normal in these cells, as demonstrated by α-tubulin staining that reveals either two centrioles or very short procentrioles (41, 42), CPAP was not detectable on centrioles in the centrobin knockdown cells (Fig. 5B). Importantly, reconstitution of centrobin expression in these knockdown cells by exogenous expression of Myc-tagged full-length centrobin (which is resistant to the centrobin siRNA-mediated depletion; Fig. 5A) resulted in restoration of CPAP levels on the centrioles (Fig. 5C). This finding, while reiterating that centrobin is essential for centriole duplication, proves the specificity of the centrobin depletion-dependent effect on centriolar localization of CPAP. These results also show that the centriolar recruitment of CPAP is a downstream event that happens only after centrobin is localized to the procentrioles.

FIGURE 5.

Centrobin depletion results in loss of CPAP from the centrosomes. A, HeLa cells were transfected with control or centrobin siRNAs for 48 h, followed by retransfection with control or Myc-centrobin-expressing vectors. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with anti-Myc, anti-centrobin, and anti-tubulin antibodies to demonstrate the knockdown of centrobin and expression of Myc centrobin. B, HeLa cells were transfected with control or centrobin siRNA for 72 h and stained with anti-centrobin (blue), anti-CPAP (red), and anti-α-tubulin (green) antibodies. C, HeLa cells were treated as described in A, followed by retransfection with Myc-centrobin vector and staining with anti-CPAP (blue), anti-Myc (red), and α-tubulin (green) antibodies. Scale bar for microscopy images, 2 μm. Images in A and B were acquired using the Olympus FV10i microscope and are maximum intensity projections of Z stacks.

Centriolar Levels and Function of CPAP Are Restored upon Reintroduction of Centrobin in Centrobin-depleted Cells

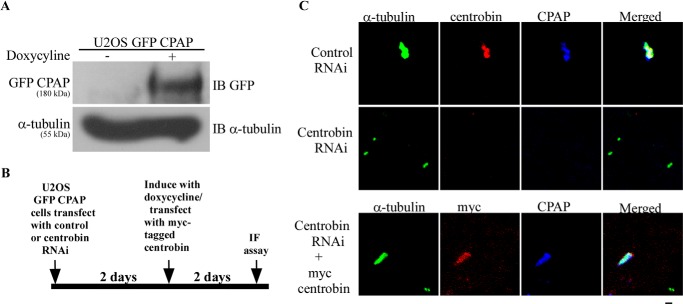

Earlier, we have shown that although the recruitment of centrobin to the centrioles is unaffected in CPAP-depleted cells, centriole elongation is blocked in centrobin-depleted CPAP-overexpressing cells (41). However, whether the centriolar level of CPAP was affected in the centrobin-depleted CPAP-overexpressing cells was not studied. Fig. 5 shows that endogenous CPAP on the centrioles was inhibited upon depletion of centrobin. Therefore, to address whether CPAP can localize to the centriole in the absence of centrobin, CPAP was overexpressed in centrobin-depleted cells, and the effect on centriole elongation was studied. U2OS cells that were inducible for exogenous GFP-CPAP expression were transfected with control or centrobin siRNA and treated with doxycycline to induce GFP-CPAP expression, as depicted in Fig. 6B. Cells were stained with anti-tubulin, anti-centrobin, and anti-CPAP antibodies and examined for centriolar CPAP levels as well as elongated centrioles. Interestingly, despite the high cellular levels of GFP-CPAP upon doxycycline treatment (Fig. 6A), centriolar localization of CPAP and centriole elongation were not detected in the centrobin-depleted CPAP-overexpressing cells (Fig. 6C, top and middle). This indicates that the presence of centrobin on the centrioles is essential for the persistence of CPAP on them as well as for the subsequent centriole elongation.

FIGURE 6.

Centrobin-depleted cells do not show CPAP recruitment to the centrioles and centriole elongation. A, U2OS cells expressing inducible GFP-CPAP were transfected with control or centrobin siRNA for 2 days and treated with doxycycline for another 2 days. Cells were then subjected to immunoblotting with anti-GFP and anti-tubulin antibodies. B, experimental scheme of C. C, cells described in A were stained with anti-α-tubulin (green), anti-centrobin (red), and anti-CPAP (blue) antibodies to mark the centrioles (top and middle rows). Cells described in A were retransfected with Myc-tagged centrobin after 2 days of RNAi treatment and treated with doxycycline, followed by staining with anti-α-tubulin (green), anti-Myc (red), and anti-CPAP (blue) antibodies (bottom row). Scale bar, 2 μm. Images were acquired using the Olympus FV10i microscope and are maximum intensity projections of Z stacks. IF, immunofluorescence.

The observation that overexpression of CPAP in centrobin-depleted cells did not restore CPAP levels on the centrioles suggests that the requirement of centrobin localization on the centrioles is critical and cannot be bypassed. To realize whether centriolar localization of CPAP is dependent specifically on centrobin levels, centrobin was reintroduced into centrobin-depleted U2OS cells, CPAP levels were induced by treatment with doxycycline, and centriolar elongation was determined. Reintroduction of centrobin using the Myc-centrobin-expressing vector in the centrobin-depleted cells resulted in the reappearance of CPAP on the centrioles as well as restoration of centriole elongation function (Fig. 6C, bottom). This observation suggests that the persistence of CPAP levels on the centrioles and its function require the continuous presence of centrobin. These observations prove that CPAP functions downstream of centrobin in the centriole biogenesis pathway.

In summary, our study reveals that centrobin mediates centriole duplication primarily by stabilizing CPAP levels on the centrioles. Considering the ability of the N-terminal region of centrobin to interact with CPAP and the previous studies demonstrating that centrobin has a C-terminal centriole targeting motif (41, 47), our observations suggest that centrobin is instrumental in the recruitment and maintenance of CPAP on the centrioles, which in turn is critical for the elongation of new centrioles.

DISCUSSION

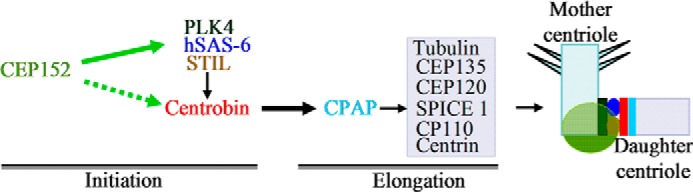

Previously, we reported that centrobin is required for the centrioles to elongate during duplication by binding to tubulin (41). In this study, using the mass spectrometry approach, we identified CEP152 as a binding partner of centrobin (Table 1). CEP152 initiates centriole biogenesis by recruiting PLK4 and CPAP to the procentrioles (25, 39). Therefore, our new observation that centrobin and CEP152 interact indicates an early role for centrobin, in addition to its involvement during the elongation stage, in the initiation of centriole duplication. CEP152 depletion prevents centrobin localization to the centrioles, whereas CEP152 is localized to the centrioles in the absence of centrobin. Potential reasons could be 1) direct or indirect interaction between CEP152 and centrobin facilitates localization/recruitment of centrobin to the centriole, or 2) the presence of CEP152 or its interacting partners on the procentriole is required for the recruitment of centrobin (Fig. 7). Our observation that exogenous expression of the CEP152-interacting fragment of centrobin failed to alter the centriolar levels of CEP152 indicates that centrobin is recruited to the centriole biogenesis site after CEP152. The same region in centrobin has CPAP-binding properties, and overexpression of this fragment results in disappearance of CPAP from the centrioles in a dominant negative manner, suggesting that centrobin-CPAP interaction is essential for the recruitment of CPAP to centrioles. Therefore, we believe that CEP152-mediated CPAP recruitment to the centrioles that was reported previously (25, 39), is centrobin-dependent.

FIGURE 7.

Model depicting the order in which proteins are recruited to the procentriole. Centriole duplication is initiated by CEP152-mediated localization of PLK4 to the proximal end of the mother centriole. CEP152 binds to centrobin directly (dotted green arrow) or indirectly through other interacting partners (solid green arrow), which facilitates recruitment of centrobin to the procentrioles. Direct interaction between centrobin and CPAP mediates elongation of the daughter centriole.

While this manuscript was in preparation, it was reported that ectopically expressed Drosophila centrobin is in a complex with several centriolar proteins, including asterless and SAS-4, the respective homologs of human CEP152 and CPAP (6). However, how these interactions facilitate centriole biogenesis has not been studied. Interestingly, centrobin was not found to be essential for centriole duplication in Drosophila (6) as opposed to humans. This suggests that the pathway for centriole biogenesis in humans is significantly different, highlighting the importance of identifying and mapping the interactions between centriolar proteins in humans. Our results demonstrate that the human orthologs of centrobin, asterless, and SAS-4 interact, and their interactions are critical for centriole biogenesis.

CPAP plays an important role at both the initiation and elongation stages of centriole duplication (29, 30, 33, 34). Depletion of CPAP results in inhibition of PLK4-mediated initiation of centriole biogenesis (30), whereas its overexpression leads to de novo centriole elongation (29, 33, 34). Centrobin also has a critical role in centriole elongation through its interaction with tubulin (41). Both centrobin and CPAP have the ability to bind to the αβ-dimer of tubulin directly (41). The CPAP(1–996) fragment that interacts with centrobin also possesses the tubulin binding property (50, 51). The observations that centrobin-tubulin interaction is required for CPAP-mediated centriole elongation (41) and that CPAP fails to localize to and causes elongation of the centrioles upon centrobin depletion further validate the notion that centrobin-CPAP interaction facilitates the recruitment of CPAP to the centrioles.

In addition, it appears that the centrobin-CPAP interaction is critical for maintaining stable levels of CPAP on the centrioles. This has been supported by our observation that cells expressing the CPAP-binding fragments of centrobin lack CPAP signal on centrioles at S phase. Our results suggest that the CPAP-binding N-terminal fragment of centrobin causes loss of CPAP from both the daughter and mother centrioles, possibly by blocking the interaction between endogenous centrobin and CPAP. It is likely that centrobin-mediated maintenance of CPAP levels on the centrioles and the ability of these two proteins to form a complex with tubulin, as shown in our previous report (41), orchestrate microtubule triplet formation during centriole elongation by forming a scaffold.

As reported earlier, centrobin was recruited to the procentrioles in CPAP-depleted cells (41). However, our current study shows that CPAP levels on the centrioles are blocked upon centrobin depletion or dominant negatively when the centrobin-CBD fragment is expressed. This fragment, however, lacks the centriole localization motif. CPAP disappears from the centrioles in centrobin-depleted cells, and its levels are restored only upon reintroduction of centrobin in these cells. Intriguingly, exogenously expressed CPAP could not localize to the centrioles in the absence of centrobin, indicating that localization and persistence of CPAP levels on the centrioles require centrobin. Overall, these observations prove that the precise function of centrobin is to orchestrate the centriolar localization of CPAP and stabilize its levels on the centrioles for centriole elongation during duplication.

Our current study establishes that centriolar localization of CPAP does not occur in the absence of centrobin. However, it is not clear how centrobin regulates the CPAP levels on centrioles. Importantly, the centriole localization domain of centrobin is situated in its C terminus (47); therefore, the centrobin(1–364) and the centrobin-CBD fragments do not localize to the centrosome but act dominant negatively by blocking the interactions between endogenous centrobin and CPAP. However, how centrobin-CBD causes disappearance of CPAP from the centrioles, especially from preexisting mothers, is not known. It has been reported that a constant dynamic exchange occurs between the centrosomal and cytoplasmic pools of CPAP (5). It is possible that centrobin-CBD, which is mostly cytoplasmic (Fig. 2D, middle) exerts a dominant negative (blocking) effect on the cytoplasmic pool of endogenous centrobin and CPAP that ultimately affects the exchange, resulting in the loss of CPAP, even from the preexisting centrioles.

Because centrobin is thought to be a daughter centriolar protein (42), it is not clear how the full-length endogenous centrobin regulates CPAP levels on the mother centrioles. We envisage three scenarios. First, centrobin is not daughter centriole-restricted. Under hydroxyurea and nocodazole treatment conditions, centrobin was detected on the new mother centriole (41), indicating that it can be present on the mother centrioles, at least in lower amounts. Second, under hydroxyurea and nocodazole treatment conditions, a phosphorylated form of centrobin was detected at the cellular level (44); however, the centriolar localization of the phosphorylated centrobin has never been addressed. Third, CPAP is known to undergo proteasomal degradation (33). It is possible that centrobin-CPAP interaction stabilizes CPAP on the centrioles and that, in the absence of centrobin, CPAP is targeted for proteasomal degradation. These scenarios require further investigation.

In summary, we report that centrobin plays a critical role during duplication, at both the initiation and elongation stages of centriole biogenesis. Interaction of centrobin and CPAP facilitates localization of CPAP to the newly forming centrioles and stabilizes its levels on the centrioles for duplication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kunsoo Rhee, Dr. Ingrid Hoffmann, Dr. Tang, Dr. Pierre Gonczy, and Dr. Puligilla for invaluable help in providing reagents. We also thank the Cell and Molecular Imaging Facility and the Regenerative Medicine/Cell Biology and Hollings Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Facility at the Medical University of South Carolina for support and cooperation.

This work was supported by internal funds from the Department of Surgery and the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Medical University of South Carolina.

- CPAP

- centrosomal protein 4.1-associated protein

- IB

- immunoblot

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- IPTG

- isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside

- aa

- amino acids

- CBD

- CPAP-binding domain

- HU

- hydroxyurea.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lüders J., Stearns T. (2007) Microtubule-organizing centres: a re-evaluation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 161–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bornens M. (2002) Centrosome composition and microtubule anchoring mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Job D., Valiron O., Oakley B. (2003) Microtubule nucleation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 111–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nigg E. A., Raff J. W. (2009) Centrioles, centrosomes, and cilia in health and disease. Cell 139, 663–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kitagawa D., Kohlmaier G., Keller D., Strnad P., Balestra F. R., Flückiger I., Gönczy P. (2011) Spindle positioning in human cells relies on proper centriole formation and on the microcephaly proteins CPAP and STIL. J. Cell Sci. 124, 3884–3893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hinchcliffe E. H., Sluder G. (2001) Centrosome duplication: three kinases come up a winner! Curr. Biol. 11, R698–R701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hinchcliffe E. H., Li C., Thompson E. A., Maller J. L., Sluder G. (1999) Requirement of Cdk2-cyclin E activity for repeated centrosome reproduction in Xenopus egg extracts. Science 283, 851–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Meraldi P., Lukas J., Fry A. M., Bartek J., Nigg E. A. (1999) Centrosome duplication in mammalian somatic cells requires E2F and Cdk2-cyclin A. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 88–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lacey K. R., Jackson P. K., Stearns T. (1999) Cyclin-dependent kinase control of centrosome duplication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 2817–2822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pihan G. A., Purohit A., Wallace J., Knecht H., Woda B., Quesenberry P., Doxsey S. J. (1998) Centrosome defects and genetic instability in malignant tumors. Cancer Res. 58, 3974–3985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pihan G. A., Purohit A., Wallace J., Malhotra R., Liotta L., Doxsey S. J. (2001) Centrosome defects can account for cellular and genetic changes that characterize prostate cancer progression. Cancer Res. 61, 2212–2219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thornton G. K., Woods C. G. (2009) Primary microcephaly: do all roads lead to Rome? Trends Genet. 25, 501–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guernsey D. L., Jiang H., Hussin J., Arnold M., Bouyakdan K., Perry S., Babineau-Sturk T., Beis J., Dumas N., Evans S. C., Ferguson M., Matsuoka M., Macgillivray C., Nightingale M., Patry L., Rideout A. L., Thomas A., Orr A., Hoffmann I., Michaud J. L., Awadalla P., Meek D. C., Ludman M., Samuels M. E. (2010) Mutations in centrosomal protein CEP152 in primary microcephaly families linked to MCPH4. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87, 40–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nigg E. A. (2007) Centrosome duplication: of rules and licenses. Trends Cell Biol. 17, 215–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lange B. M., Gull K. (1995) A molecular marker for centriole maturation in the mammalian cell cycle. J. Cell Biol. 130, 919–927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vorobjev I. A., Chentsov Y. S. (1980) The ultrastructure of centriole in mammalian tissue culture cells. Cell Biol. Int. Rep. 4, 1037–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Robbins E., Gonatas N. K. (1964) The ultrastructure of a mammalian cell during the mitotic cycle. J. Cell Biol. 21, 429–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Azimzadeh J., Bornens M. (2007) Structure and duplication of the centrosome. J. Cell Sci. 120, 2139–2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Doxsey S. (2001) Re-evaluating centrosome function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 688–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Doxsey S., McCollum D., Theurkauf W. (2005) Centrosomes in cellular regulation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 411–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Delattre M., Gönczy P. (2004) The arithmetic of centrosome biogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 117, 1619–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Loncarek J., Khodjakov A. (2009) Ab ovo or de novo? Mechanisms of centriole duplication. Mol. Cells 27, 135–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Strnad P., Gönczy P. (2008) Mechanisms of procentriole formation. Trends Cell Biol. 18, 389–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Andersen J. S., Wilkinson C. J., Mayor T., Mortensen P., Nigg E. A., Mann M. (2003) Proteomic characterization of the human centrosome by protein correlation profiling. Nature 426, 570–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dzhindzhev N. S., Yu Q. D., Weiskopf K., Tzolovsky G., Cunha-Ferreira I., Riparbelli M., Rodrigues-Martins A., Bettencourt-Dias M., Callaini G., Glover D. M. (2010) Asterless is a scaffold for the onset of centriole assembly. Nature 467, 714–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bettencourt-Dias M., Rodrigues-Martins A., Carpenter L., Riparbelli M., Lehmann L., Gatt M. K., Carmo N., Balloux F., Callaini G., Glover D. M. (2005) SAK/PLK4 is required for centriole duplication and flagella development. Curr. Biol. 15, 2199–2207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Habedanck R., Stierhof Y. D., Wilkinson C. J., Nigg E. A. (2005) The Polo kinase Plk4 functions in centriole duplication. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 1140–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leidel S., Delattre M., Cerutti L., Baumer K., Gönczy P. (2005) SAS-6 defines a protein family required for centrosome duplication in C. elegans and in human cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kohlmaier G., Loncarek J., Meng X., McEwen B. F., Mogensen M. M., Spektor A., Dynlacht B. D., Khodjakov A., Gönczy P. (2009) Overly long centrioles and defective cell division upon excess of the SAS-4-related protein CPAP. Curr. Biol. 19, 1012–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kleylein-Sohn J., Westendorf J., Le Clech M., Habedanck R., Stierhof Y. D., Nigg E. A. (2007) Plk4-induced centriole biogenesis in human cells. Dev. Cell 13, 190–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chen Z., Indjeian V. B., McManus M., Wang L., Dynlacht B. D. (2002) CP110, a cell cycle-dependent CDK substrate, regulates centrosome duplication in human cells. Dev. Cell 3, 339–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gönczy P. (2012) Towards a molecular architecture of centriole assembly. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 425–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tang C. J., Fu R. H., Wu K. S., Hsu W. B., Tang T. K. (2009) CPAP is a cell-cycle regulated protein that controls centriole length. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 825–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmidt T. I., Kleylein-Sohn J., Westendorf J., Le Clech M., Lavoie S. B., Stierhof Y. D., Nigg E. A. (2009) Control of centriole length by CPAP and CP110. Curr. Biol. 19, 1005–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kalay E., Yigit G., Aslan Y., Brown K. E., Pohl E., Bicknell L. S., Kayserili H., Li Y., Tüysüz B., Nürnberg G., Kiess W., Koegl M., Baessmann I., Buruk K., Toraman B., Kayipmaz S., Kul S., Ikbal M., Turner D. J., Taylor M. S., Aerts J., Scott C., Milstein K., Dollfus H., Wieczorek D., Brunner H. G., Hurles M., Jackson A. P., Rauch A., Nürnberg P., Karagüzel A., Wollnik B. (2011) CEP152 is a genome maintenance protein disrupted in Seckel syndrome. Nat. Genet. 43, 23–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gul A., Hassan M. J., Hussain S., Raza S. I., Chishti M. S., Ahmad W. (2006) A novel deletion mutation in CENPJ gene in a Pakistani family with autosomal recessive primary microcephaly. J. Hum. Genet. 51, 760–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McIntyre R. E., Lakshminarasimhan Chavali P., Ismail O., Carragher D. M., Sanchez-Andrade G., Forment J. V., Fu B., Del Castillo Velasco-Herrera M., Edwards A., van der Weyden L., Yang F., Sanger Mouse Genetics Project, Ramirez-Solis R., Estabel J., Gallagher F. A., Logan D. W., Arends M. J., Tsang S. H., Mahajan V. B., Scudamore C. L., White J. K., Jackson S. P., Gergely F., Adams D. J. (2012) Disruption of mouse cenpj, a regulator of centriole biogenesis, phenocopies seckel syndrome. PLoS Genet. 8, e1003022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hatch E. M., Kulukian A., Holland A. J., Cleveland D. W., Stearns T. (2010) Cep152 interacts with Plk4 and is required for centriole duplication. J. Cell Biol. 191, 721–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cizmecioglu O., Arnold M., Bahtz R., Settele F., Ehret L., Haselmann-Weiss U., Antony C., Hoffmann I. (2010) Cep152 acts as a scaffold for recruitment of Plk4 and CPAP to the centrosome. J. Cell Biol. 191, 731–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blachon S., Gopalakrishnan J., Omori Y., Polyanovsky A., Church A., Nicastro D., Malicki J., Avidor-Reiss T. (2008) Drosophila asterless and vertebrate Cep152 are orthologs essential for centriole duplication. Genetics 180, 2081–2094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gudi R., Zou C., Li J., Gao Q. (2011) Centrobin-tubulin interaction is required for centriole elongation and stability. J. Cell Biol. 193, 711–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zou C., Li J., Bai Y., Gunning W. T., Wazer D. E., Band V., Gao Q. (2005) Centrobin: a novel daughter centriole-associated protein that is required for centriole duplication. J. Cell Biol. 171, 437–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Balestra F. R., Strnad P., Flückiger I., Gönczy P. (2013) Discovering regulators of centriole biogenesis through siRNA-based functional genomics in human cells. Dev. Cell 25, 555–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee J., Jeong Y., Jeong S., Rhee K. (2010) Centrobin/NIP2 is a microtubule stabilizer whose activity is enhanced by PLK1 phosphorylation during mitosis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25476–25484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jeffery J. M., Urquhart A. J., Subramaniam V. N., Parton R. G., Khanna K. K. (2010) Centrobin regulates the assembly of functional mitotic spindles. Oncogene 29, 2649–2658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Issa L., Mueller K., Seufert K., Kraemer N., Rosenkotter H., Ninnemann O., Buob M., Kaindl A. M., Morris-Rosendahl D. J. (2013) Clinical and cellular features in patients with primary autosomal recessive microcephaly and a novel CDK5RAP2 mutation. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 8, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jeong Y., Lee J., Kim K., Yoo J. C., Rhee K. (2007) Characterization of NIP2/centrobin, a novel substrate of Nek2, and its potential role in microtubule stabilization. J. Cell Sci. 120, 2106–2116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Paoletti A., Moudjou M., Paintrand M., Salisbury J. L., Bornens M. (1996) Most of centrin in animal cells is not centrosome-associated and centrosomal centrin is confined to the distal lumen of centrioles. J. Cell Sci. 109, 3089–3102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stucke V. M., Silljé H. H., Arnaud L., Nigg E. A. (2002) Human Mps1 kinase is required for the spindle assembly checkpoint but not for centrosome duplication. EMBO J. 21, 1723–1732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hsu W. B., Hung L. Y., Tang C. J., Su C. L., Chang Y., Tang T. K. (2008) Functional characterization of the microtubule-binding and -destabilizing domains of CPAP and d-SAS-4. Exp. Cell Res. 314, 2591–2602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hung L. Y., Chen H. L., Chang C. W., Li B. R., Tang T. K. (2004) Identification of a novel microtubule-destabilizing motif in CPAP that binds to tubulin heterodimers and inhibits microtubule assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 2697–2706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]