Background: The contribution of TERT to cellular reprogramming is unclear.

Results: KO of TERT reduces the reprogramming efficiency of somatic cells, and continuous growth induces chromosome abnormalities; enzymatically inactive TERT rescues the efficiency.

Conclusion: TERT has a telomerase-independent role in somatic cell reprogramming.

Significance: Understanding the cellular reprogramming process is crucial for the clinical applications of induced pluripotent stem cells.

Keywords: Bioinformatics, Induced Pluripotent Stem (iPS) Cell, Microarray, Reprogramming, Telomeres

Abstract

Reactivation of the endogenous telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) catalytic subunit and telomere elongation occur during the reprogramming of somatic cells to induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells. However, the role of TERT in the reprogramming process is unclear. To clarify its function, the reprogramming process was examined in TERT-KO somatic cells. To exclude the effect of telomere elongation, tail-tip fibroblasts (TTFs) from first generation TERT-KO mice were used. Although iPS cells were successfully generated from TERT-KO TTFs, the efficiency of reprogramming these cells was markedly lower than that of WT TTFs. The gene expression profiles of iPS cells induced from TERT-KO TTFs were similar to those of WT iPS cells and ES cells, and TERT-KO iPS cells formed teratomas that differentiated into all three germ layers. These data indicate that TERT plays an extratelomeric role in the reprogramming process, but its function is dispensable. However, TERT-KO iPS cells showed transient defects in growth and teratoma formation during continuous growth. In addition, TERT-KO iPS cells developed chromosome fusions that accumulated with increasing passage numbers, consistent with the fact that TERT is essential for the maintenance of genome structure and stability in iPS cells. In a rescue experiment, an enzymatically inactive mutant of TERT (D702A) had a positive effect on somatic cell reprogramming of TERT-KO TTFs, which confirmed the extratelomeric role of TERT in this process.

Introduction

The potential roles of induced pluripotent stem (iPS)4 cells in clinical regenerative medicine and the mechanisms involved in their induction by the reprogramming of somatic cells have been studied previously (1). However, despite a wealth of research, the precise mechanisms underlying the reprogramming process are not fully understood (2). Overexpression of the four reprogramming factors, Klf4, Sox2, Oct3/4, and c-Myc, which are also known as the Yamanaka factors, can induce pluripotency in somatic cells (1, 3); however, only a minority of somatic cells can be reprogrammed (4). Recent reports suggest that these four transcription factors can induce other cell types in addition to pluripotent cells (5, 6). Moreover, stochastic mechanisms are also thought to be involved in the generation of iPS cells (7, 8). Therefore, somatic cell reprogramming appears to be the result of multiple processes.

Telomeres are repetitive TTAGGG sequences located at the end of chromosomes that protect against abnormal fusions, recombination, and degradation (9). Telomere shortening occurs with each round of cell division (10), and this process may cause genomic instability. Telomeres can be elongated by the addition of TTAGGG repeat sequences, a process that is mediated by telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), the catalytic subunit of the enzyme telomerase. Reprogramming of somatic cells requires multiple cell divisions; therefore, iPS cells must be able to sustain telomerase activity and maintain elongated telomeres (11). Although TERT is inactivated in most mature somatic cells, its constitutive activation in stem cells and germ cells allows life-long cellular proliferation (12, 13). Telomeres play a role in the proliferation and differentiation of cells (14), and endogenous TERT expression is induced during somatic cell reprogramming (15). During this process, somatic cells acquire indefinite proliferative capacity, as well as the ability to differentiate into the three germ layers as follows: ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm. Some reports suggest that TERT increases the efficiency of somatic cell reprogramming; for example, the induction of TERT enhances the generation of human iPS cells from fetal, neonatal, and adult primary cells, as well as those from dyskeratosis congenita patients (16, 17). By contrast, another study using telomerase RNA component (TERC)-KO somatic cells showed that elongation of the telomere does not affect the reprogramming efficiency of somatic cells when the telomere length is not already shortened at the beginning of the reprogramming process (11).

It is possible that TERT plays a role in the reprogramming of somatic cells that is independent of telomere elongation. To examine this hypothesis, reprogramming experiments were performed using somatic cells from first generation (F1) TERT-KO mice, which have long telomeres. TERT-KO somatic cells could be reprogrammed to iPS cells by introducing the four reprogramming factors; however, the efficiency of reprogramming was lower than that of WT somatic cells. In rescue experiments, an enzymatically inactive mutant of TERT (D702A) improved the reprogramming efficiency of TERT-KO somatic cells. These data suggest that TERT has extratelomeric activity during the reprogramming of somatic cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Induction of iPS Cells from Adult Tail-tip Fibroblasts (TTFs)

The induction of iPS cells from adult mouse TTFs was performed as described previously (18). To estimate the status of cellular reprogramming, a retroviral DsRed vector and a lentiviral early transposon Oct4 and Sox2 enhancer (EOS) vector were introduced into the cells to monitor the silencing activity of the retrovirus vector and the promoter activity of Oct3/4 and Sox2, respectively. Four days after induction, cells were reseeded on STO feeder layers, and the numbers of colonies were counted from day 11 of the culture. For the TERT-KO TTF rescue experiment, WT TERT or enzymatically inactive TERT (D702A mutant) was introduced into TERT-KO TTFs 1 day prior to induction by the four reprogramming factors. The TERT-WT and TERT D702A lentiviruses were generated using HEK 293T cells, as described previously (18).

Cell Culture

STO feeder cells were treated with 40 μg/ml mitomycin C for 2 h and plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells per 55 cm2. The iPS cells were cultured on mitomycin C-treated STO cells in knockout DMEM (Invitrogen) containing 15% FBS, ESGRO (Millipore), l-glutamine, nonessential amino acids, β-mercaptoethanol, 50 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin, and 20 μg/ml ascorbic acid (19). For RNA extraction, feeder cells were depleted by two rounds of incubation on a 0.2% gelatin-coated dish.

EdU Assay

Cell cycle entry was analyzed using Click-iT EdU flow cytometry assay kits (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, WT and TERT-KO iPS cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well. The following day, the cells were treated with 10 μm EdU for 1.5 h and then washed with 1% BSA in PBS. The cells were fixed with Click-iT fixative at room temperature for 15 min. After a further wash, the cells were permeabilized by incubation with Click-iT saponin-based permeabilization and wash reagent for 15 min. Click-iT reaction mixture was then added to the permeabilized cells. Finally, the cells were washed with 1× Click-iT saponin-based permeabilization and wash reagent, and then analyzed using the FACSCalibur platform (BD Biosciences).

Embryoid Body (EB) Formation

For the formation of EBs, iPS cells were dissociated to form a single cell suspension and reseeded into Petri dishes at a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml.

Plasmids

The retroviral plasmids for iPS cell induction and the DsRed, EOS, and PGK lentiviral plasmids have been described previously (18). The CSII-EF-mTERT-IRES2-Venus plasmid was a gift from Dr. Hiroyuki Miyoshi (RIKEN Bioresource Center, Tsukuba, Japan). This plasmid carries a point mutation in TERT and was created using the following primers designed using the QuikChange Primer Design Program (Agilent Technologies): forward, 5′-gtactttgttaaggcagctgtgaccggggcctatg-3′; reverse, 5′-cataggccccggtcacagctgccttaacaaagtac-3′. PCR was performed using KOD-Plus polymerase (Toyobo) and the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 18 cycles of 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C for 1 min, and 68 °C for 15 min. The PCR product was digested with DpnI and then transformed into Escherichia coli. The mutation was confirmed by sequencing with the following primer, 5′-gctacgggagctgtcacaag-3′.

Gene Expression Analysis

Primers and probes specific for the four endogenous and retroviral reprogramming factors and the pluripotent cell markers (Nanog, ECAT1, and ERas) were designed as described previously (18). Transcript levels were determined using the 7500 Fast Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems).

Teratoma Formation

To produce teratomas, 1 × 106 cells were suspended in Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and injected into nude mice. After 3–4 weeks, tumors were fixed with PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with H&E.

Telomere Length Assay

Telomere lengths were analyzed using the Telo TAGGG telomere length assay kit (Roche Applied Science), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 1.5 μg of genomic DNA was digested with HinfI and RsaI. The digested DNA was hybridized to a digoxigenin-labeled telomere probe and detected using an anti-digoxigenin antibody.

Karyotype Analysis

Cell karyotypes were generated and analyzed at the Central Institute for Experimental Animals in Japan. Chromosomes from 50 metaphases were counted for each genotype and at each passage. Representative characteristics for each chromosome were aligned to identify fusion events.

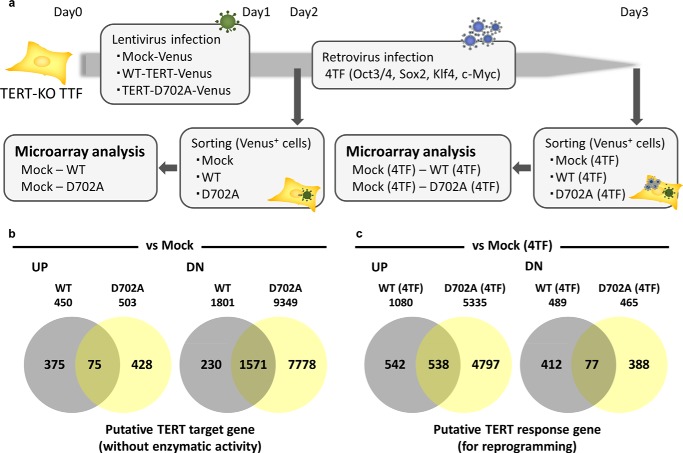

Microarray Analysis

TERT-KO TTFs were infected with lentivirus containing mock-Venus, TERT-WT-Venus, or TERT-D702A-Venus. Two days later, infected cells were identified by the level of Venus fluorescence. One day after infection of cells with the retroviral reprogramming factors, cells were collected by Venus fluorescence. The experimental design is summarized in Fig. 6a. Expression profiles were analyzed using a whole mouse genome 44K3D-Gene Mouse Oligo chip 24K (Agilent Technologies). Fluorescence intensities were detected using a Scan-Array Life Scanner (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), and photomultiplier tube levels were adjusted to achieve 0.1–0.5% pixel saturation. Each TIFF image was analyzed with GenePix Pro software version 6.0 (Molecular Devices). The data were filtered to remove low confidence measurements and normalized globally per array such that the median signal intensity was set at 50. The signatures were calculated using genes that were at least 2-fold up- or down-regulated. To determine the gene expression signature of TERT-KO iPS cells at passage 43, genes that were up- and down-regulated genes compared with the other iPSCs we examined were determined. To characterize the molecular backgrounds of the signature genes, an enrichment analysis of canonical pathways and gene ontology biological processes (c2-cp and c5-bp gene sets in MsigDB version 3.0 (16) was performed using the gene ontology term finder (17). p < 5% was used as a threshold.

FIGURE 6.

Microarray analysis of the TERT target and TERT-response genes. a, experimental design of the microarray analyses. TERT-KO TTFs were mock (vector only)-infected or infected with WT or enzymatically inactive TERT (D702A). Samples were collected before and after the induction of reprogramming by infection of the cells with the Klf4, Sox2, Oct3/4, and c-Myc retroviruses. The gene expression profiles in TERT-transfected cells were compared with those in mock (vector only)-infected cells both before and after induction. b, numbers of genes that were up- or down-regulated in noninduced TERT-WT-infected and TERT D702A-infected TTFs. c, number of genes that were up- or down-regulated in induced TERT-WT-infected and TERT D702A-infected TTFs. The names of the genes are listed in supplemental Tables S2 and S4 for noninduced cells and induced cells, respectively.

RESULTS

Preparation and Characterization of TTFs from TERT-KO Mice

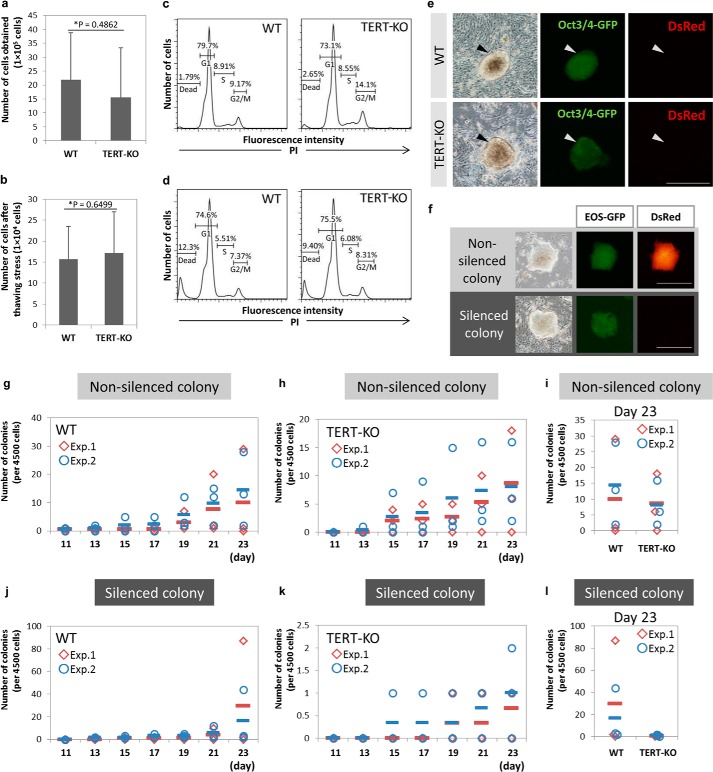

To analyze the function of TERT in somatic cell reprogramming, adult TTFs were prepared from TERT-KO mice. To exclude the effects of shortened telomeres, TTFs from F1 mice were used, as described in a previous study that analyzed the telomere RNA component (TERC) mutant (11). The efficiency of reprogramming is related to proliferative capacity; therefore, the viability and growth properties of the TERT-KO TTFs were examined (4). The numbers of viable TTFs obtained from single TERT-KO and WT mouse tails were comparable (Fig. 1a), and there was no significant difference after thawing stress (Fig. 1b). To clarify the role of TERT in the reprogramming of somatic cells, the four reprogramming factors, Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc, were introduced into WT and TERT-KO TTFs as retroviruses. The two types of cells showed similar cell cycle patterns both before (Fig. 1c) and after (Fig. 1d) the introduction of the reprogramming factors. These data indicate that there were no significant differences between the viabilities and growth properties of the TERT-KO and WT TTFs.

FIGURE 1.

Characterization and reprogramming of TTFs from WT and TERT-KO mice. a and b, numbers of cells obtained from single tails of WT and TERT-KO mice before (a) and after (b) freeze-thawing. Data are represented as the mean ± S.D. of n = 8 (a) or n = 6 (b) mice per genotype. p values were performed by Student's t tests. c and d, cell cycle analysis performed by propidium iodide staining of TTFs from WT and TERT-KO mice before (c) and 4 days after (d) the induction of reprogramming. The percentages of cells in each stage of the cell cycle are indicated. e and f, representative images of nonsilenced EOS-GFP-positive and DsRed-positive and silenced EOS-GFP-positive and DsRed-negative colonies. Scale bar, 500 μm. g–i, efficiencies of nonsilenced colony formation of WT (g) and TERT-KO (h) TTFs in two separate experiments. Four days after induction, cells were reseeded on STO feeder layers, and the numbers of colonies were counted across days 11–23 of the culture. A comparison of the nonsilenced colony forming efficiencies of WT and TERT-KO TTFs on day 23 is show in i. j–l, efficiencies of silenced colony formation of WT (j) and TERT-KO (k) TTFs in two separate experiments. A comparison of the silenced colony forming efficiencies of WT and TERT-KO TTFs on day 23 is shown in l. g–l, each symbol indicates an independent well, and the horizontal bars indicate the mean value for each experiment.

KO of TERT Decreases the Efficiency of Somatic Cell Reprogramming of TTFs

To estimate the status of cellular reprogramming after the introduction of the four reprogramming factors, the endogenous activities of Oct3/4 and Sox2 were monitored using a lentiviral EOS vector, and the silencing of retroviral genes was monitored using a retroviral DsRed vector. Reprogrammed cells were identified as those that were EOS-positive and DsRed-negative (Fig. 1e) (18, 20). The colonies began to merge ∼2 weeks after induction, and the numbers of colonies were counted at days 11–23 (Fig. 1, f–l). 23 days after transfection, the number of silenced colonies of WT TTFs was ∼10-fold higher than the number of silenced colonies of TERT-KO TTFs (Fig. 1l), indicating that TERT contributes to somatic cell reprogramming.

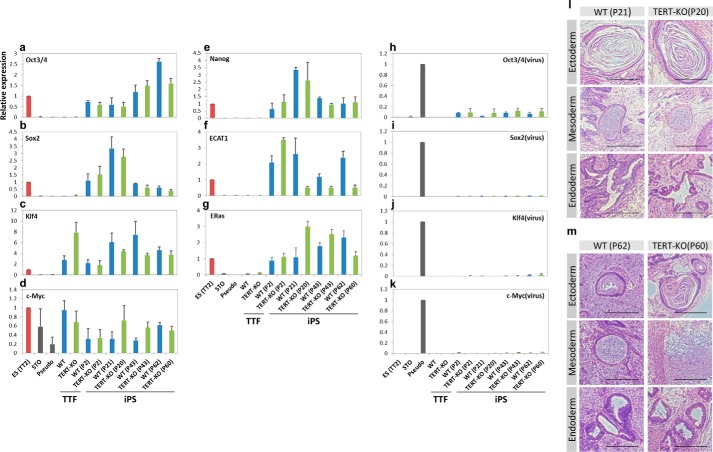

Although the efficiency of induction was low, candidate colonies from EOS-positive/DsRed-negative reprogrammed cells were successfully obtained from TERT-KO TTFs. These colonies were maintained and expanded, and their gene expression profiles and differentiation capacities were determined. Real time PCR analyses revealed that the endogenous mRNA levels of the two of the reprogramming factors, Oct3/4 and Sox2, were up-regulated in both WT and TERT-KO reprogrammed cells compared with parental TTFs (Fig. 2, a–d). In addition, compared with WT TTFs, pseudo colony cells (cells that were infected with the four Yamanaka reprogramming factors but were not morphologically ES cell-like), and STO cells, the mRNA levels of three other pluripotent cell markers, namely Nanog, ECAT1, and ERas, were also up-regulated in TERT-KO reprogrammed cells, and their expression levels were comparable with those in ES cells (Fig. 2, e–g). Because silencing of retroviral genes is an important requirement for iPS cells, the expression levels of the retroviral reprogramming factors were also analyzed. Both WT and TERT-KO reprogrammed cells had very low expression levels of all four viral genes (Fig. 2, h–k). These data indicate that TERT-KO-reprogrammed cells have comparable gene expression profiles to WT iPS cells.

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of reprogrammed cells from WT and TERT-KO TTFs. a–g, real time PCR analyses of the endogenous gene expression profiles of the four Yamanaka iPS cell-inducible factors (a–d) and ES cell-specific markers (e–g) in reprogrammed cells from WT and TERT-KO TTFs, as well as ES cells, mouse adult TTFs, STO cells, and pseudo colony cells. Pseudo colony cells were generated by infection with the four Yamanaka reprogramming factors, but the cells were not morphologically ES cell-like and were negative for Nanog-GFP expression. h–k, real time PCR analyses of the silencing of retroviral genes in each cell type. a–k, passage numbers (P) of the cells are indicated. Expression levels were normalized to those of the ES cells (for endogenous genes) or the pseudo colony cells (for retroviral genes). Data are represented as the mean ± S.D. of n = 3 replicates. l and m, differentiation capacity of reprogrammed WT and TERT-KO cells at passages around 20 (l) and around 60 (m) injected into nude mice. Sections of the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm layers from WT and TERT-KO reprogrammed cell teratomas were stained with H&E. Scale bar, 200 μm.

Next, the differentiation capacity of TERT-KO reprogrammed cells was examined by injecting the cells into nude mice. After 3–4 weeks, teratomas containing tissues from all three germ layers were formed (Fig. 2l). These results demonstrate that TERT-KO reprogrammed cells are capable of forming all three germ layers, and taken together, these data indicate that TERT-KO TTFs are able to generate iPS cells.

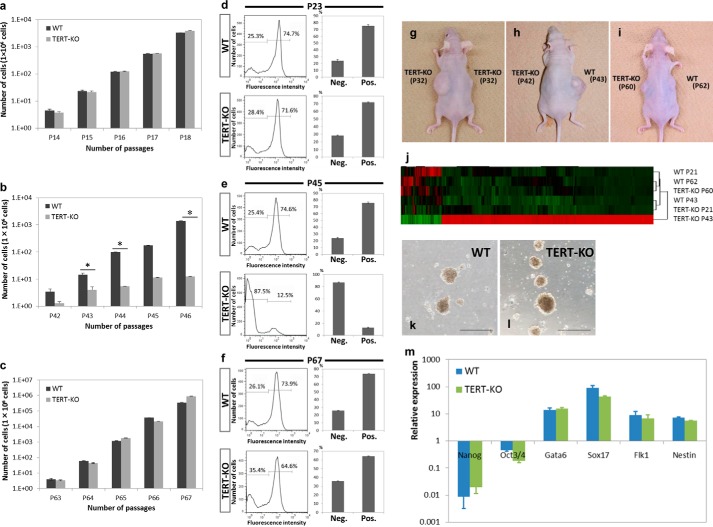

Continuous Passaging Causes a Transient Growth Defect but Has No Effect on the Gene Expression Patterns or Differentiation Capacity of TERT-KO iPS Cells

To evaluate the effect of TERT deficiency on the maintenance of pluripotency, WT and TERT-KO iPS cells were cultured continuously, and the numbers of cells and their cell cycle stages were compared at several time points. At passages 14–18, the proliferation of TERT-KO iPS cells was comparable with that of WT iPS cells (Fig. 3, a and d). The proliferative capacity of TERT-KO iPS cells was lower than that of WT iPS cells after 40 passages (Fig. 3, b and e); however, the numbers of each cell type were comparable after 60 passages (Fig. 3, c and f). At each passage, the gene expression profiles of the endogenous pluripotency genes and the silencing status of the four retroviral reprogramming factors were maintained (Fig. 2, a–k). The differentiation capacities of the WT and TERT-KO iPS cells were also analyzed by injecting iPS cells at various passages into nude mice (Fig. 3, g–i). At passage 43, WT iPS cells formed teratomas, but TERT-KO iPS cells did not (Fig. 3h and Table 1). Surprisingly, TERT-KO iPS cells at passage 60 did produce teratomas, which might be due to escape from the proliferative crisis (Figs. 3i and 2m) (21).

FIGURE 3.

Characterization of TERT-KO iPS cells during continuous passaging. a–c, numbers of WT and TERT-KO iPS cells at the indicated passage numbers. The numbers represent the total number of cells in all colonies. Data are represented as the mean ± S.D. of n = 3 replicates per genotype. *, p < 0.01 by Student's t tests. d–f, percentages of S-phase WT and TERT-KO iPS cells at passages 20 (d), 40 (e), and 60 (f) identified by EdU uptake. Data are represented as the mean ± S.D. of n = 3 replicates per genotype. g–i, teratoma formation by WT and TERT-KO iPS cells at the indicated passages. The numbers of cells injected into the left and right sides were 2.0 × 106 and 1.0 × 106 cells, respectively (g). j, an array heat map of genes from the indicated passages of iPS cells derived from WT and TERT-KO TTFs. The names of the genes included in the heat map are listed in supplemental Table S1. k and l, morphologies of EBs derived from WT (k) and TERT-KO (l) iPS cells at passages 43 and 41, respectively. m, gene expression analysis of pluripotent cell markers (Nanog and Oct3/4), endoderm markers (GATA6 and Sox17), a mesoderm marker (Flk1), and an ectoderm marker (Nestin) in EBs derived from the WT and TERT-KO iPS cells. Expression levels were normalized to those of undifferentiated iPS cells. Data are represented as the mean ± S.D. of n = 3 replicates.

TABLE 1.

Teratoma formation of WT and TERT-KO iPS cells at passages higher than 40

| Genotype | Passage | No. of injected cells | Days | Teratoma formation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 43 | 1.0 x 106 | 37 | o |

| WT | 45 | 1.0 x 106 | 42 | o |

| WT | 45 | 6.0 x 106 | 42 | o |

| WT | 44 | 1.0 x 106 | 29 | o |

| TERT-KO | 42 | 1.0 x 106 | 37 | × |

| TERT-KO | 42 | 1.0 x 106 | 42 | × |

| TERT-KO | 42 | 6.0 x 106 | 42 | × |

| TERT-KO | 44 | 1.5 x 106 | 27 | × |

To investigate the transient defects in growth and teratoma formation further, and to identify changes at the molecular level, microarray analyses of reprogrammed WT and TERT-KO iPS cells at various passages were performed. A cluster analysis identified 792 and 157 genes that were up-regulated and down-regulated in TERT-KO iPS cells at passage 43, respectively (Fig. 3j and supplemental Table S1). A gene ontology analysis also revealed that the terms “cell adhesion” and “morphogenesis” were down-regulated in TERT-KO iPS cells at passage 43 (Table 2). The array data were then compared with the results of a recently published analysis of Mbd3-deficient cells (22), which reported close to 100% efficient iPS cell reprogramming upon Mbd3 depletion and identified deterministic gene expression patterns for this reprogramming. Genes that were commonly down-regulated in TERT-KO iPS cells at passage 43 (compared with WT cells at the same passage) and up-regulated in Mbd3-KO cells at day 8 (compared with WT cells at day 11) were identified (supplemental Table S1). These inversely correlated genes may be responsible for the deficiencies in the proliferation and differentiation potential of TERT-KO iPS cells at passage 43. To determine whether the failure of these cells to form teratomas was caused by a loss of differentiation capacity, iPS cells at passages higher than 40 were analyzed using an in vitro EB differentiation assay. TERT-KO iPS cells at passage 41 formed EBs and had high expression levels of genes that represent the differentiation of the three germ layers (Fig. 3, k–m). These data indicate that, around passage 40, TERT-KO iPS cells display defective teratoma formation due to a decrease in proliferative capacity rather than a loss of differentiation capacity.

TABLE 2.

Gene ontology terms that were up- or down-regulated in TERT-KO iPS cells at passage 43

| Up-regulated gene ontology terms |

| ORGAN_DEVELOPMENT |

| TISSUE_DEVELOPMENT |

| RESPONSE_TO_WOUNDING |

| BONE_REMODELING |

| SYSTEM_DEVELOPMENT |

| TISSUE_REMODELING |

| XENOBIOTIC_METABOLIC_PROCESS |

| REGULATION_OF_BLOOD_PRESSURE |

| ECTODERM_DEVELOPMENT |

| RESPONSE_TO_XENOBIOTIC_STIMULUS |

| RESPONSE_TO_EXTERNAL_STIMULUS |

| SYSTEM_PROCESS |

| SENSORY_ORGAN_DEVELOPMENT |

| WOUND_HEALING |

| EPIDERMIS_DEVELOPMENT |

| MULTICELLULAR_ORGANISMAL_DEVELOPMENT |

| LOCOMOTORY_BEHAVIOR |

| MUSCLE_DEVELOPMENT |

| ANATOMICAL_STRUCTURE_DEVELOPMENT |

| MYOBLAST_DIFFERENTIATION |

| DEVELOPMENTAL_MATURATION |

| PROTEIN_SECRETION |

| HEMOSTASIS |

| SKELETAL_DEVELOPMENT |

| EPITHELIAL_TO_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION |

| REGULATION_OF_BIOLOGICAL_QUALITY |

| EXCRETION |

| MUSCLE_CELL_DIFFERENTIATION |

| REGULATION_OF_AXONOGENESIS |

| RESPONSE_TO_TOXIN |

| Down-regulated gene ontology terms |

| CALCIUM_INDEPENDENT_CELL_CELL_ADHESION |

| ANATOMICAL_STRUCTURE_MORPHOGENESIS |

| HUMORAL_IMMUNE_RESPONSE |

| ORGAN_MORPHOGENESIS |

| CELL_CELL_ADHESION |

| REGULATION_OF_CELL_ADHESION |

| REGULATION_OF_TRANSFERASE_ACTIVITY |

| CARBOXYLIC_ACID_TRANSPORT |

| ORGANIC_ACID_TRANSPORT |

| REGULATION_OF_CYCLIN_DEPENDENT_PROTEIN_KINASE_ACTIVITY |

Chromosomal Instability in TERT-KO iPS Cells

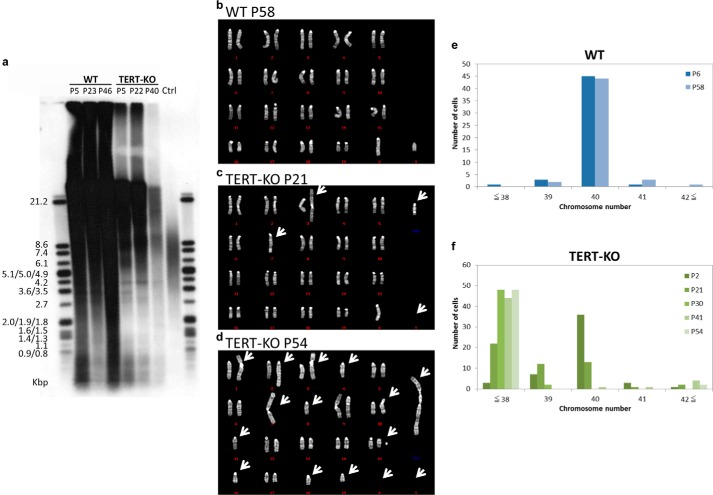

A passage-dependent decrease in growth rate and recapture of proliferative capacity have previously been reported for TERC-KO ES cells (21); therefore, the telomere length and chromosome stability of TERT-KO iPS cells were examined. Compared with WT iPS cells, TERT-KO iPS cells displayed a passage-dependent reduction in telomere length and relative signal intensity (Fig. 4a). In addition, a karyotype analysis identified a passage-dependent accumulation of chromosome fusions and the appearance of characteristically long chromosomes formed as a result of chromosomal fusions in TERT-KO iPS cells (Fig. 4, b–f). At passages 6 and 58, most WT iPS cells had a normal complement of chromosomes (n = 40) (Fig. 4e); however, after 30 passages, it was difficult to find TERT-KO cells with a normal complement of chromosomes, and most cells had 38 chromosomes or less (Fig. 4f). This accumulation of chromosome fusions increased as the cells were grown continuously up to around passage 60.

FIGURE 4.

Chromosome instability of TERT-KO iPS cells. a, telomere lengths in WT and TERT-KO iPS cells at the indicated passage numbers (P) identified by Southern blotting. The telomere lengths (kbp) are shown on the left. Ctrl indicates the loading control included in the assay kit. b–d, karyotype analyses of WT iPS cells at passage 58 (b) and TERT-KO iPS cells at passages 21 (c) and 54 (d). The arrows indicate mutated regions in TERT-KO cells. e and f, numbers of chromosomes in WT iPS cells at passages 6 and 58 (e) and in TERT-KO iPS cells at passages 2, 21, 30, 41, and 54 (f).

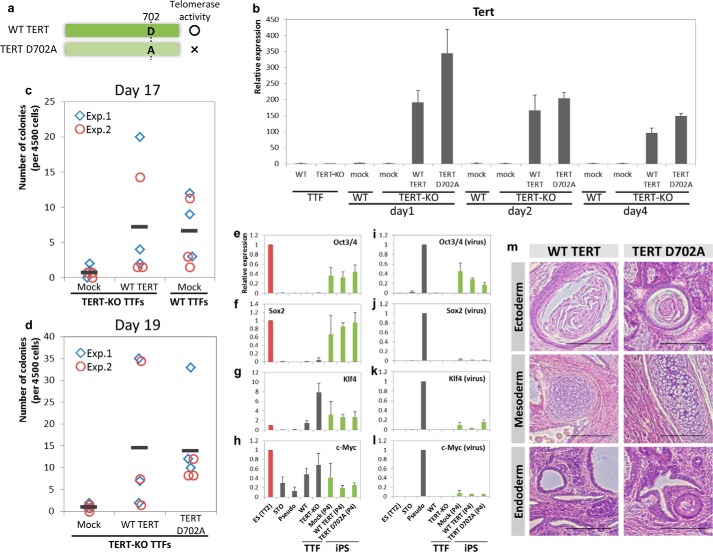

TERT Has an Extratelomeric Function in Somatic Cell Reprogramming

A deficiency in TERC, the RNA gene that serves as a template for the telomere repeat sequence (TTAGGG) elongated by TERT, is another cause of defects in telomere elongation; however, the reprogramming of somatic cells from the F1 generation of TERC-KO mice is reportedly not affected by the deficiency (11). Because the TERT-KO TTFs used in this study were generated from F1 mice, the telomere length was long enough to exclude an effect on reprogramming efficiency. Despite this fact, the reprogramming efficiency of TERT-KO TTFs was markedly lower than that of WT TTFs, which suggests an extratelomeric function of TERT in somatic cell reprogramming. To investigate this possibility, a rescue experiment was performed by introducing WT TERT or the TERT D702A mutant (23) into TERT-KO TTFs. The D702A mutant is rendered enzymatically inactive by a point mutation of aspartic acid 702 to alanine (Fig. 5a). Prior to transfection of the TERT-KO TTFs with the four reprogramming factors, the cells were pre-infected with lentiviral vectors carrying WT or mutant TERT. The expression of both WT and mutant TERT was detected 1 day after infection (Fig. 5b), and colony numbers were counted 17 days after the induction of reprogramming. As expected, the colony formation efficiency of TERT-KO TTFs was rescued by the introduction of WT TERT (Fig. 5c). Interestingly, the TERT D702A mutant also improved the colony formation efficiency 19 days after induction (Fig. 5d). Moreover, the colonies generated from the rescue of TERT-KO TTFs with WT TERT or TERT D702A showed similar expression patterns of endogenous pluripotency genes, silencing of the introduced reprogramming factors, and differentiation capacities for all three germ layers through teratoma formation (Fig. 5, e–m). Taken together, these results indicate that the colonies generated after rescue were iPS cells and that TERT plays an extratelomeric role in somatic cell reprogramming.

FIGURE 5.

Enzymatically inactive TERT rescues the reduced reprogramming efficiency of TERT-KO TTFs. a, D702A point mutation in TERT that renders it enzymatically inactive. b, expression levels of lentivirus-infected WT TERT and TERT D702A in noninfected WT and TERT-KO TTFs, mock (vector only)-infected WT TTFs, and TERT-KO TTFs infected with WT or TERT D702A. Gene expression levels were normalized to those in ES cells. Data are represented as the mean ± S.D. of n = 3 replicates. c, efficiencies of colony formation of mock (vector only)-infected WT TTFs, mock (vector only)-infected TERT-KO TTFs, and TERT-KO TTFs infected with WT TERT. Colonies were counted 17 days after the induction of reprogramming. d, efficiencies of colony formation of mock (vector only)-infected TERT-KO TTFs and TERT-KO TTFs infected with WT or mutated TERT. Colonies were counted 19 days after the induction of reprogramming. c and d, each symbol indicates an independent well, and the horizontal line indicates the mean value. e–h, real time PCR analyses of the endogenous gene expression profiles of the four Yamanaka iPS cell-inducible factors in iPS cells from TERT-KO TTFs rescued with WT TERT or TERT D702A, as well as ES cells, mouse adult TTFs, STOs, and pseudo colony cells. Pseudo colony cells were generated by infection with the four Yamanaka reprogramming factors, but the cells were not morphologically ES cell-like and were negative for Nanog-GFP expression. i–l, real time PCR analyses of the silencing of retroviral genes in the same cell types. e–l, passage numbers (P) of the cells are indicated. Expression levels were normalized to those of ES cells (for endogenous genes) or pseudo colony cells (for retroviral genes). Data are represented as the mean ± S.D. of n = 3 replicates. m, differentiation capacity of iPS cells infected WT TERT and TERT D702A vectors. Sections of the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm layers from WT and TERT-KO iPS cell teratomas were stained with H&E. Scale bar, 200 μm.

Identification of Putative TERT Target and Response Genes

To elucidate the molecular mechanism by which TERT improves the efficiency of somatic cell reprogramming, a mouse whole genome microarray analysis was performed. The gene expression profiles in mock (vector only)-infected TERT-KO TTFs were compared with those in TERT-KO TTFs infected with WT or D702A mutant TERT. The expression profiles were examined both before and after the induction of reprogramming by infection of the cells with the Klf4, Sox2, Oct3/4, and c-Myc retroviruses. An overview of the experimental design is shown in Fig. 6a. The numbers of genes that were up- or down-regulated in noninduced and reprogrammed cells compared with mock-infected TERT-KO cells are shown in Fig. 6, b and c, respectively. Prior to induction, 75 and 1571 genes were commonly up- and down-regulated, respectively, in both WT TERT- and TERT D702A-infected cells (Fig. 6b and supplemental Table S2); these genes are putative targets of enzymatically inactive TERT. When we focused specifically on transcription factors and epigenetic modifiers, histone modifiers involved in the maintenance of heterochromatin were identified as down-regulated genes, including Ezh2, Suv39h2, and HDAC9 (Table 3). TERT might relax the chromatin structure to facilitate its access by reprogramming factors. Furthermore, when compared with the array data of Mbd3-KO cells at day 4 (22), a number of positively correlated genes were identified (supplemental Table S3), including two members of the Prdm family (Prdm6 and Prdm1). Prdm6 is a known transcriptional repressor that associates with EHMT2/G9a (24), whereas Prdm1 is a known transcriptional repressor (25). In a recent study, overexpression of Prdm1 impaired embryonic stem cell maintenance (26). After induction by the four reprogramming factors, 538 and 77 genes were commonly up- or down-regulated, respectively, in both WT TERT and TERT D702A-infected TERT-KO cells compared with mock-infected TERT-KO cells (Fig. 6c and supplemental Table S4); these genes are putative TERT-response genes for reprogramming and included a number of transcription factors associated with somatic cell reprogramming, such as Esrrb and Klf17 (Table 4). Esrrb and Klf17 were enriched upon comparison with the Mbd3-KO data (supplemental Table S5) (22). Esrrb is a key regulatory factor for reprogramming, and Klf17 is reported to suppress epithelial mesenchymal transition in breast cancer (27, 28). Because mesenchymal epithelial transition is a major event during the early phase of reprogramming, suppression of the process would be expected to inhibit its progression (29, 30). Overall, the microarray data suggest that, upon induction, TERT up-regulates key genes involved in cellular reprogramming.

TABLE 3.

List of putative TERT target genes encoding transcription factors and epigenetic modifiers that were up- or down-regulated in non-induced TERT-KO TTFs infected with WT or D702A mutant TERT, compared with mock (vector only)-infected cells

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Up-regulated genes | |

| Transcription factors | |

| Hoxd11 | Homeobox D11 |

| Olig2 | Oligodendrocyte transcription factor 2 |

| Hoxd4 | Homeobox D4 |

| Klf1 | Kruppel-like factor 1 (erythroid) |

| Epigenetic modifiers | |

| No gene | |

| Down-regulated genes | |

| Transcription factors | |

| Chd7 | Chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 7 |

| Mesp1 | Mesoderm posterior 1 |

| Hhex | Hematopoietically expressed homeobox |

| Ferd3l | Fer3-like (Drosophila) |

| Sp110 | Sp110 nuclear body protein |

| Arntl2 | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like 2 |

| Zscan4c | Zinc finger and SCAN domain containing 4C |

| Tle4 | Transducin-like enhancer of split 4, homolog of Drosophila E(spl) |

| Hes7 | Hairy and enhancer of split 7 (Drosophila) |

| Zfp710 | Zinc finger protein 710 |

| Foxm1 | Forkhead box M1 |

| E2f7 | E2F transcription factor 7 |

| Etv1 | ets variant gene 1 |

| Bnc1 | Basonuclin 1 |

| Fli1 | Friend leukemia integration 1 |

| Rhox9 | Reproductive homeobox 9 |

| Npas2 | Neuronal PAS domain protein 2 |

| Uhrf1 | Ubiquitin-like, containing PHD and RING finger domains, 1 |

| Irf5 | Interferon regulatory factor 5 |

| Lmo2 | LIM domain only 2 |

| Mef2a | Myocyte enhancer factor 2A |

| Tcfec | Transcription factor EC |

| Gli1 | GLI-Kruppel family member GLI1 |

| Ets2 | E26 avian leukemia oncogene 2,3′ domain |

| Six2 | Sine oculis-related homeobox 2 homolog (Drosophila) |

| E2f2 | E2F transcription factor 2 |

| Nanog | Nanog homeobox |

| Tcfcp2l1 | Transcription factor CP2-like 1 |

| Foxa2 | Forkhead box A2 |

| Id2 | Inhibitor of DNA binding 2 |

| Hoxa13 | Homeobox A13 |

| Mafb | v-maf musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene family, protein B (avian) |

| Runx3 | Runt-related transcription factor 3 |

| Tal2 | T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia 2 |

| Mxd3 | Max dimerization protein 3 |

| Vav1 | vav1 oncogene |

| Myf5 | Myogenic factor 5 |

| Ikzf1 | IKAROS family zinc finger 1 |

| Pou2f2 | POU domain, class 2, transcription factor 2 |

| Irf8 | Interferon regulatory factor 8 |

| Dmrta2 | Doublesex and mAb-3 related transcription factor like family A2 |

| Ovol1 | OVO homolog-like 1 (Drosophila) |

| Tal1 | T-cell acute lymphocytic leukemia 1 |

| Stat4 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 4 |

| Sfpi1 | SFFV proviral integration 1 |

| Etv2 | ets variant gene 2 |

| Gbx2 | Gastrulation brain homeobox 2 |

| Mybl2 | Myeloblastosis oncogene-like 2 |

| Dmrt1 | Doublesex and mAb-3 related transcription factor 1 |

| Rbl1 | Retinoblastoma-like 1 (p107) |

| Pou3f1 | POU domain, class 3, transcription factor 1 |

| Epas1 | Endothelial PAS domain protein 1 |

| Lyl1 | Lymphoblastomic leukemia 1 |

| Atf3 | Activating transcription factor 3 |

| Mycl1 | v-myc myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog 1, lung carcinoma derived (avian) |

| Otx1 | Orthodenticle homolog 1 (Drosophila) |

| Grhl1 | Grainyhead-like 1 (Drosophila) |

| Batf | Basic leucine zipper transcription factor, ATF-like |

| Myf6 | Myogenic factor 6 |

| Dlx3 | Distal-less homeobox 3 |

| Hif3a | Hypoxia-inducible factor 3, α subunit |

| Epigenetic modifiers | |

| Ezh2 | Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (Drosophila) |

| Hdac9 | Histone deacetylase 9 |

| Prdm6 | PR domain containing 6 |

| Prdm1 | PR domain containing 1, with ZNF domain |

| Padi4 | Peptidyl arginine deiminase, type IV |

| Suv39h2 | Suppressor of variegation 3–9 homolog 2 (Drosophila) |

TABLE 4.

List of putative TERT-response genes encoding transcription factors and epigenetic modifiers that were up- or down-regulated in induced TERT-KO TTFs infected with WT or D702A mutant TERT, compared with mock (vector only)-infected cells

| Description | |

|---|---|

| Up-regulated genes | |

| Transcription factors | |

| Fev | FEV (ETS oncogene family) |

| Myod1 | Myogenic differentiation 1 |

| Ascl3 | Achaete-scute complex homolog 3 (Drosophila) |

| Rax | Retina and anterior neural fold homeobox |

| Esrrb | Estrogen-related receptor, β |

| Ovol2 | Ovo-like 2 (Drosophila) |

| Zfp354c | Zinc finger protein 354C |

| Irx3 | Iroquois-related homeobox 3 (Drosophila) |

| Sim1 | Single-minded homolog 1 (Drosophila) |

| Zfp618 | Zinc finger protein 618 |

| Vsx1 | Visual system homeobox 1 homolog (zebrafish) |

| Zfhx4 | Zinc finger homeodomain 4 |

| Onecut3 | One cut domain, family member 3 |

| Nkx2-3 | NK2 transcription factor related, locus 3 (Drosophila) |

| Sox10 | SRY-box containing gene 10 |

| Hoxb8 | Homeobox B8 |

| Hmx1 | H6 homeobox 1 |

| Rfx2 | Regulatory factor X, 2 (influences HLA class II expression) |

| Sp6 | Trans-acting transcription factor 6 |

| Tead1 | TEA domain family member 1 |

| Foxl1 | Forkhead box L1 |

| Rfx5 | Regulatory factor X, 5 (influences HLA class II expression) |

| Zfp641 | Zinc finger protein 641 |

| Klf17 | Kruppel-like factor 17 |

| Hes5 | Hairy and enhancer of split 5 (Drosophila) |

| Foxo4 | Forkhead box O4 |

| Epigenetic modifiers | |

| No gene | |

| Down-regulated genes | |

| Transcription factors | |

| Dlx5 | Distal-less homeobox 5 |

| Tbx10 | T-box 10 |

| Adipoq | Adiponectin, C1Q, and collagen domain containing |

| Myf6 | Myogenic factor 6 |

| Zfp57 | Zinc finger protein 57 |

| Tlx1 | T-cell leukemia, homeobox 1 |

| Eomes | Eomesodermin homolog (Xenopus laevis) |

| Smad9 | MAD homolog 9 (Drosophila) |

| Hoxa2 | Homeobox A2 |

| Esx1 | Extraembryonic, spermatogenesis, homeobox 1 |

| Klf1 | Kruppel-like factor 1 (erythroid) |

| Epigenetic modifiers | |

| No gene | |

DISCUSSION

The reprogramming of somatic cells allows unipotent differentiated cells to become pluripotent. TERT, the enzyme involved in telomere synthesis, is expressed at low levels in somatic cells; however, during the reprogramming process, TERT is reactivated and telomeres are re-elongated (11). In addition to telomere elongation, TERT has other functions, including RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity and modulation of β-catenin signaling (31, 32). This study demonstrates that TERT also plays a role in somatic cell reprogramming that is independent of telomere elongation.

Reprogramming and Enzymatic TERT Activity

The reprogramming efficiency of TERT-KO TTFs was approximately one-tenth that of WT TTFs; however, despite this reduction in efficiency, the reprogrammed cells from TERT-KO TTFs showed characteristics typical of iPS cells, including similar gene expression profiles, silencing of retroviral genes, and the ability to differentiate into the three germ layers. These data indicate that TERT plays an important but nonessential role in somatic cell reprogramming. A previous study demonstrated that TERC-KO mice begin to show stem cell defects related to telomeric shortening from the fifth generation onward (33). Because the TERT-KO TTFs used in this study were generated from F1 KO mice, the telomeres were not shortened, and defects were not observed (Fig. 4) (23). Shortened telomeres are related to a significant decrease in the reprogramming efficiency of TERC-KO somatic cells; however, if telomeres are sufficiently long at the beginning of reprogramming, telomere shortening may not affect the efficiency of reprogramming (11). Taken together, the current evidence suggests that the low reprogramming efficiency of TERT-KO TTFs is not caused by shortened telomeres. Because another study reported that TERT functions as an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (31), it would be interesting to elucidate the role played by RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in somatic cell reprogramming.

Interestingly, the reprogramming efficiency of TERT-KO TTFs was improved by infection of the cells with the TERT D702A mutant, indicating that enzymatically inactive TERT also has reprogramming activity. Enzymatically inactive TERT D702A induces epithelial cell proliferation through the β-catenin pathway (34), and the inhibition of GSK-3β, which leads to β-catenin activation, is one of the major signals involved in maintaining pluripotency (35). It is possible that the TERT D702A mutant activates β-catenin to rescue the reprogramming efficiency. Recent reports suggest that Esrrb is a downstream effector of GSK-3β inhibition that is required to maintain pluripotency (36, 37). Intriguingly, the microarray analysis described here indicated that Esrrb is a putative TERT target gene involved in reprogramming. A recent study demonstrated that TERT binds several proteins (31), and these TERT-binding proteins are candidate effectors for potentiating the efficiency of reprogramming. Because some of these candidate proteins are reported to have functions related to pluripotency (38), it would be interesting to investigate their potential roles in somatic cell reprogramming. Furthermore, Esrrb plays an important role at the late phase of reprogramming (39), and retrovirus silencing also occurs as a late event during this process (40, 41). Here, TERT-KO TTFs produced more nonsilenced colonies than silenced colonies (Fig. 1, h and k). Therefore, it will be important to analyze the relationship between TERT, Esrrb, and silencing.

Continuous Passaging of Pluripotent TERT-KO iPS Cells Leads to Abnormal Chromosomes

The number of abnormal chromosomes in TERT-KO iPS cells increased in proportion to the passage number. After 30 passages, no cells with a normal complement of chromosomes were observed (Fig. 4f). As predicted from the function of telomeres in protecting chromosomal ends, the majority of abnormalities in TERT-KO iPS cells were caused by chromosomal end fusions (Fig. 4d). However, the expression profiles of pluripotency-associated genes were maintained regardless of the passage number. In addition, TERT-KO iPS cells retained the capacity to differentiate into all three germ layers, even at passage numbers greater than 60. However, at around passage 40, TERT-KO iPS cells showed a transient decrease in the proliferation rate and a failure to form teratomas, even though the cells were able to differentiate into the three germ layers through EB formation in vitro (Fig. 3, k–m). Although the mechanism underlying the transient defect is unknown, this interesting phenomenon was also previously reported in TERC-KO ES cells and TERT-knockdown ES cells (21, 42).

In pluripotent cells such as ES cells and iPS cells, the cell cycle checkpoint mediated by p53 is nonfunctional (43). Therefore, pluripotent cells are exposed to continuous genomic mutations, which leads to a potential risk of tumorigenicity. If these cells are to be used for clinical applications, it is important that such a risk is avoided. However, in this study, the presence of abnormal chromosomes did not affect the gene expression pattern in the undifferentiated state nor the differentiation capacity of iPS cells. Furthermore, in addition to chromosomal fusions, amplifications were also detected, as observed previously in ATM-KO iPS cells (18). Therefore, analysis of chromosomal abnormalities is essential for the future clinical applications of iPS cells, and it will also be important to establish a culture method capable of maintaining the genomic stability of these cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. H. Miyoshi (RIKEN Bioresource Center) for the TERT lentiviral vector. We also thank Dr. J. Ellis (University of Toronto) and Dr. A. Hotta (Kyoto University) for the EOS selection system. Support for the core institutes for iPS cell research was provided by Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, a Grant-in-Aid for the Global Century COE program from Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology to Keio University, and the Keio University Medical Science Fund.

This work was supported by PRESTO of the Japan Science and Technology Agency, funds for the Development of Human Resources in Science and Technology of the Program to Disseminate Tenure Tracking System for Tenure Track Program at the Sakaguchi Laboratory and Scientific Research (C), Grant-in-aid 247121 for JSPS Fellows from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and in part by a grant from the Project for the Realization of Regenerative Medicine.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S5.

- iPS

- induced pluripotent stem cell

- EB

- embryoid bodies

- EOS

- early transposon Oct4 and Sox2 enhancer

- F1

- first generation

- TERC

- telomerase RNA component

- TERT

- telomerase reverse transcriptase

- TTF

- tail-tip fibroblast

- TERC

- telomere RNA component

- EdU

- 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine.

REFERENCES

- 1. Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. (2006) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mikkelsen T. S., Hanna J., Zhang X., Ku M., Wernig M., Schorderet P., Bernstein B. E., Jaenisch R., Lander E. S., Meissner A. (2008) Dissecting direct reprogramming through integrative genomic analysis. Nature 454, 49–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takahashi K., Tanabe K., Ohnuki M., Narita M., Ichisaka T., Tomoda K., Yamanaka S. (2007) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131, 861–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hanna J., Saha K., Pando B., van Zon J., Lengner C. J., Creyghton M. P., van Oudenaarden A., Jaenisch R. (2009) Direct cell reprogramming is a stochastic process amenable to acceleration. Nature 462, 595–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Han D. W., Greber B., Wu G., Tapia N., Araúzo-Bravo M. J., Ko K., Bernemann C., Stehling M., Schöler H. R. (2011) Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into epiblast stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 66–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Efe J. A., Hilcove S., Kim J., Zhou H., Ouyang K., Wang G., Chen J., Ding S. (2011) Conversion of mouse fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes using a direct reprogramming strategy. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 215–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yamanaka S. (2009) Elite and stochastic models for induced pluripotent stem cell generation. Nature 460, 49–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nagamatsu G., Saito S., Kosaka T., Takubo K., Kinoshita T., Oya M., Horimoto K., Suda T. (2012) Optimal ratio of transcription factors for somatic cell reprogramming. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 36273–36282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blackburn E. H. (2001) Switching and signaling at the telomere. Cell 106, 661–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harley C. B., Futcher A. B., Greider C. W. (1990) Telomeres shorten during ageing of human fibroblasts. Nature 345, 458–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marion R. M., Strati K., Li H., Tejera A., Schoeftner S., Ortega S., Serrano M., Blasco M. A. (2009) Telomeres acquire embryonic stem cell characteristics in induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 4, 141–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Flores I., Benetti R., Blasco M. (2006) Telomerase regulation and stem cell behaviour. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 254–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu L., Bailey S. M., Okuka M., Muñoz P., Li C., Zhou L., Wu C., Czerwiec E., Sandler L., Seyfang A., Blasco M. A., Keefe D. L. (2007) Telomere lengthening early in development. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1436–1441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jiang H., Ju Z., Rudolph K. L. (2007) Telomere shortening and ageing. Z. Gerontol. Geriatr. 40, 314–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stadtfeld M., Nagaya M., Utikal J., Weir G., Hochedlinger K. (2008) Induced pluripotent stem cells generated without viral integration. Science 322, 945–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park I.-H., Zhao R., West J. A., Yabuuchi A., Huo H., Ince T. A., Lerou P. H., Lensch M. W., Daley G. Q. (2008) Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors. Nature 451, 141–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Agarwal S., Loh Y.-H., McLoughlin E. M., Huang J., Park I.-H., Miller J. D., Huo H., Okuka M., Dos Reis R. M., Loewer S., Ng H.-H., Keefe D. L., Goldman F. D., Klingelhutz A. J., Liu L., Daley G. Q. (2010) Telomere elongation in induced pluripotent stem cells from dyskeratosis congenita patients. Nature 464, 292–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kinoshita T., Nagamatsu G., Kosaka T., Takubo K., Hotta A., Ellis J., Suda T. (2011) Ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) deficiency decreases reprogramming efficiency and leads to genomic instability in iPS cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 407, 321–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Esteban M. A., Wang T., Qin B., Yang J., Qin D., Cai J., Li W., Weng Z., Chen J., Ni S. (2010) Vitamin C enhances the generation of mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 6, 71–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hotta A., Cheung A. Y., Farra N., Vijayaragavan K., Séguin C. A., Draper J. S., Pasceri P., Maksakova I. A., Mager D. L., Rossant J., Bhatia M., Ellis J. (2009) Isolation of human iPS cells using EOS lentiviral vectors to select for pluripotency. Nat. Methods 6, 370–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Niida H., Shinkai Y., Hande M. P., Matsumoto T., Takehara S., Tachibana M., Oshimura M., Lansdorp P. M., Furuichi Y. (2000) Telomere maintenance in telomerase-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells: characterization of an amplified telomeric DNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 4115–4127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rais Y., Zviran A., Geula S., Gafni O., Chomsky E., Viukov S., Mansour A. A., Caspi I., Krupalnik V., Zerbib M., Maza I., Mor N., Baran D., Weinberger L., Jaitin D. A., Lara-Astiaso D., Blecher-Gonen R., Shipony Z., Mukamel Z., Hagai T., Gilad S., Amann-Zalcenstein D., Tanay A., Amit I., Novershtern N., Hanna J. H. (2013) Deterministic direct reprogramming of somatic cells to pluripotency. Nature 502, 65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yuan X., Ishibashi S., Hatakeyama S., Saito M., Nakayama J., Nikaido R., Haruyama T., Watanabe Y., Iwata H., Iida M., Sugimura H., Yamada N., Ishikawa F. (1999) Presence of telomeric G-strand tails in the telomerase catalytic subunit TERT knockout mice. Genes Cells 4, 563–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Davis C. A., Haberland M., Arnold M. A., Sutherland L. B., McDonald O. G., Richardson J. A., Childs G., Harris S., Owens G. K., Olson E. N. (2006) PRISM/PRDM6, a transcriptional repressor that promotes the proliferative gene program in smooth muscle cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 2626–2636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vincent S. D., Dunn N. R., Sciammas R., Shapiro-Shalef M., Davis M. M., Calame K., Bikoff E. K., Robertson E. J. (2005) The zinc finger transcriptional repressor Blimp1/Prdm1 is dispensable for early axis formation but is required for specification of primordial germ cells in the mouse. Development 132, 1315–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nagamatsu G., Kosaka T., Kawasumi M., Kinoshita T., Takubo K., Akiyama H., Sudo T., Kobayashi T., Oya M., Suda T. (2011) A germ cell-specific gene, Prmt5, works in somatic cell reprogramming. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 10641–10648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Feng B., Jiang J., Kraus P., Ng J. H., Heng J. C., Chan Y. S., Yaw L. P., Zhang W., Loh Y. H., Han J., Vega V. B., Cacheux-Rataboul V., Lim B., Lufkin T., Ng H. H. (2009) Reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells with orphan nuclear receptor Esrrb. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 197–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gumireddy K., Li A., Gimotty P. A., Klein-Szanto A. J., Showe L. C., Katsaros D., Coukos G., Zhang L., Huang Q. (2009) KLF17 is a negative regulator of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis in breast cancer. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1297–1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Samavarchi-Tehrani P., Golipour A., David L., Sung H. K., Beyer T. A., Datti A., Woltjen K., Nagy A., Wrana J. L. (2010) Functional genomics reveals a BMP-driven mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in the initiation of somatic cell reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell 7, 64–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li R., Liang J., Ni S., Zhou T., Qing X., Li H., He W., Chen J., Li F., Zhuang Q., Qin B., Xu J., Li W., Yang J., Gan Y., Qin D., Feng S., Song H., Yang D., Zhang B., Zeng L., Lai L., Esteban M. A., Pei D. (2010) A mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition initiates and is required for the nuclear reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell 7, 51–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maida Y., Yasukawa M., Furuuchi M., Lassmann T., Possemato R., Okamoto N., Kasim V., Hayashizaki Y., Hahn W. C., Masutomi K. (2009) An RNA-dependent RNA polymerase formed by TERT and the RMRP RNA. Nature 461, 230–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Park J.-I., Venteicher A. S., Hong J. Y., Choi J., Jun S., Shkreli M., Chang W., Meng Z., Cheung P., Ji H., McLaughlin M., Veenstra T. D., Nusse R., McCrea P. D., Artandi S. E. (2009) Telomerase modulates Wnt signalling by association with target gene chromatin. Nature 460, 66–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Blasco M. A., Lee H. W., Hande M. P., Samper E., Lansdorp P. M., DePinho R. A., Greider C. W. (1997) Telomere shortening and tumor formation by mouse cells lacking telomerase RNA. Cell 91, 25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Choi J., Southworth L. K., Sarin K. Y., Venteicher A. S., Ma W., Chang W., Cheung P., Jun S., Artandi M. K., Shah N., Kim S. K., Artandi S. E. (2008) TERT promotes epithelial proliferation through transcriptional control of a Myc- and Wnt-related developmental program. PLoS Genet. 4, e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Silva J., Barrandon O., Nichols J., Kawaguchi J., Theunissen T. W., Smith A. (2008) Promotion of reprogramming to ground state pluripotency by signal inhibition. PLoS Biol. 6, e253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Martello G., Sugimoto T., Diamanti E., Joshi A., Hannah R., Ohtsuka S., Göttgens B., Niwa H., Smith A. (2012) Esrrb is a pivotal target of the gsk3/tcf3 axis regulating embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell 11, 491–504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Festuccia N., Osorno R., Halbritter F., Karwacki-Neisius V., Navarro P., Colby D., Wong F., Yates A., Tomlinson S. R., Chambers I. (2012) Esrrb is a direct nanog target gene that can substitute for nanog function in pluripotent cells. Cell Stem Cell 11, 477–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhu Q., Meng L., Hsu J. K., Lin T., Teishima J., Tsai R. Y. (2009) GNL3L stabilizes the TRF1 complex and promotes mitotic transition. J. Cell Biol. 185, 827–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Buganim Y., Faddah D. A., Cheng A. W., Itskovich E., Markoulaki S., Ganz K., Klemm S. L., van Oudenaarden A., Jaenisch R. (2012) Single-cell expression analyses during cellular reprogramming reveal an early stochastic and a late hierarchic phase. Cell 150, 1209–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Brambrink T., Foreman R., Welstead G. G., Lengner C. J., Wernig M., Suh H., Jaenisch R. (2008) Sequential expression of pluripotency markers during direct reprogramming of mouse somatic cells. Cell Stem Cell 2, 151–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Stadtfeld M., Maherali N., Breault D. T., Hochedlinger K. (2008) Defining molecular cornerstones during fibroblast to iPS cell reprogramming in mouse. Cell Stem Cell 2, 230–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yang C., Przyborski S., Cooke M. J., Zhang X., Stewart R., Anyfantis G., Atkinson S. P., Saretzki G., Armstrong L., Lako M. (2008) A key role for telomerase reverse transcriptase unit in modulating human embryonic stem cell proliferation, cell cycle dynamics, and in vitro differentiation. Stem Cells 26, 850–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ungewitter E., Scrable H. (2010) Δ40p53 controls the switch from pluripotency to differentiation by regulating IGF signaling in ESCs. Genes Dev. 24, 2408–2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.