Background: Post-translational SUMO modification of TDG weakens its DNA binding and was proposed to regulate dissociation of a tight enzyme-product complex.

Results: In vitro sumoylation of TDG by SUMO-1 and SUMO-2 is efficient for free and DNA-bound TDG.

Conclusion: E2-mediated sumoylation is not selective for product-bound TDG but could potentially stimulate product release.

Significance: Our findings inform the mechanism and role of TDG sumoylation.

Keywords: Base Excision Repair (BER), DNA Methylation, DNA Repair, Enzyme Turnover, Post-translational Modification (PTM), Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO), Sumoylation, Ubiquitin-conjugating Enzyme (E2 Enzyme)

Abstract

Thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) initiates the repair of G·T mismatches that arise by deamination of 5-methylcytosine (mC), and it excises 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine, oxidized forms of mC. TDG functions in active DNA demethylation and is essential for embryonic development. TDG forms a tight enzyme-product complex with abasic DNA, which severely impedes enzymatic turnover. Modification of TDG by small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) proteins weakens its binding to abasic DNA. It was proposed that sumoylation of product-bound TDG regulates product release, with SUMO conjugation and deconjugation needed for each catalytic cycle, but this model remains unsubstantiated. We examined the efficiency and specificity of TDG sumoylation using in vitro assays with purified E1 and E2 enzymes, finding that TDG is modified efficiently by SUMO-1 and SUMO-2. Remarkably, we observed similar modification rates for free TDG and TDG bound to abasic or undamaged DNA. To examine the conjugation step directly, we determined modification rates (kobs) using preformed E2∼SUMO-1 thioester. The hyperbolic dependence of kobs on TDG concentration gives kmax = 1.6 min−1 and K1/2 = 0.55 μm, suggesting that E2∼SUMO-1 has higher affinity for TDG than for the SUMO targets RanGAP1 and p53 (peptide). Whereas sumoylation substantially weakens TDG binding to DNA, TDG∼SUMO-1 still binds relatively tightly to AP-DNA (Kd ∼50 nm). Although E2∼SUMO-1 exhibits no specificity for product-bound TDG, the relatively high conjugation efficiency raises the possibility that E2-mediated sumoylation could stimulate product release in vivo. This and other implications for the biological role and mechanism of TDG sumoylation are discussed.

Introduction

DNA glycosylases liberate modified or mismatched bases from DNA by cleaving the N-glycosidic bond, producing an apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP)2 site, and DNA integrity is restored by follow-on base excision repair (BER). Many DNA glycosylases form a tight enzyme-product complex with AP-DNA, which can prevent the processing of additional substrates (i.e. enzymatic turnover). A prominent example is thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG), which removes derivatives of 5-methylcytosine (mC) arising from deamination or oxidation. TDG excises thymine from G·T mispairs (1, 2) as needed to protect against C→T mutations caused by mC deamination. It also participates in active DNA demethylation, which likely accounts for findings that depletion of TDG causes embryonic lethality in mice (3, 4). One established pathway for active DNA demethylation involves TDG excision of 5-formylcytosine or 5-carboxylcytosine (5, 6), oxidation derivatives of mC generated by TET (ten-eleven translocation) enzymes (6–10).

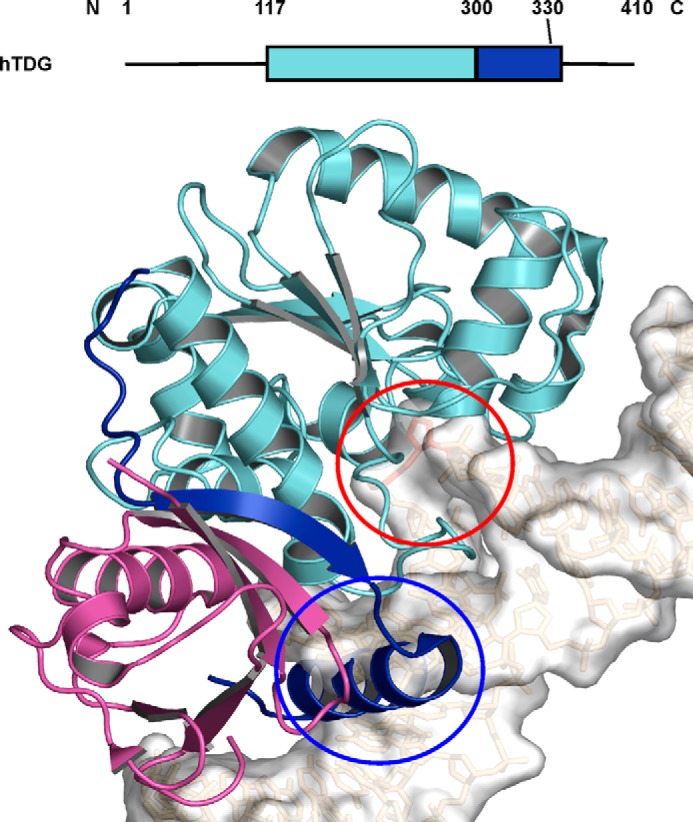

The in vitro activity of TDG is severely hampered by tight binding to its AP-DNA product (under limiting enzyme conditions) (11–15), and it was proposed that this problem is circumvented in vivo by post-translational modification. TDG is modified by small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) proteins at a single lysine residue (Lys-330, human) (16). Sumoylation of TDG weakens its binding to DNA substrates and abasic product (16–18). As shown in Fig. 1, crystal structures of sumoylated TDG (catalytic domain) indicate that SUMO stabilizes an otherwise transient α-helix that suppresses DNA binding via steric effects (17, 18).

FIGURE 1.

Putative mechanism by which sumoylation of TDG suppresses binding to DNA. Because a crystal structure has not been solved for sumoylated TDG bound to DNA, we show a model of this complex to illustrate how sumoylation likely suppresses DNA binding. The model was generated by aligning the structure of sumoylated TDG (PDB ID code 1WYW) with the structure of TDG bound to abasic DNA (PDB ID code 2RBA); only sumoylated TDG is shown. The graphic depiction of full-length TDG shows structured regions as rectangles (colored to correspond with the model below), whereas unstructured regions are depicted as lines. The catalytic core (117–300) and C-terminal region (301–332) of human TDG are colored cyan and blue, respectively, and SUMO-1 is colored magenta. The β-strand and α-helix in the unstructured C-terminal region of TDG (blue) are thought to be stabilized by SUMO-1, and the helix would likely form a steric clash with DNA (circled in blue). The abasic site is flipped into the active site of the catalytic domain (circled in red).

Remarkably, sumoylation of TDG was found to modestly enhance its G·U glycosylase activity under limiting enzyme (steady-state) conditions (16). This seemingly contradictory finding can likely be explained by the high affinity of TDG for G·U mispairs (19, 20). Sumoylation weakens but does not preclude binding to G·U mispairs, and its enhancing effect on product release leads to more efficient steady-state turnover. However, unmodified TDG has much weaker affinity for G·T relative to G·U mispairs (20, 21), and sumoylation of TDG completely diminishes its G·T glycosylase activity (16).

As such, a model was needed to explain how sumoylation might enhance G·T glycosylase activity. It was proposed that sumoylation occurs selectively for TDG in the enzyme-product complex, i.e. after base excision and before release of AP-DNA and that SUMO is enzymatically removed from TDG after product release to allow processing of additional substrates (16). Thus, glycosylase activity for G·T and other substrates was proposed to involve sumoylation and subsequent desumoylation of TDG for each catalytic cycle of the enzyme.

This model has gained much attention (22–24), given that TDG is the only enzyme for which catalytic turnover is thought to be regulated by sumoylation, and one of only two enzymes (25) for which enzymatic activity is altered by interactions with SUMO isoforms. In most cases, sumoylation serves other functions, including effects on subcellular localization and protein interactions (26, 27), with roles in processes such as chromatin remodeling, DNA repair (28, 29), apoptotic signaling (30), and localization to promyelocytic leukemia protein bodies (31, 32).

Although the proposal that sumoylation of product-bound TDG followed by desumoylation is required for each enzymatic cycle seems to be generally accepted, it remains to be substantiated, for G·T mispairs or any other TDG substrate. To begin the process of testing this model, we employed standard in vitro sumoylation assays using purified SUMO-activating and -conjugating enzymes (E1 and E2). We examined the efficiency of modification by SUMO-1 versus SUMO-2 and tested the prediction that sumoylation is specific for TDG when it is bound to AP-DNA. We also monitored the rate of TDG sumoylation by the preformed E2∼SUMO thioester, as a function of TDG concentration, and in the presence and absence of DNA. Our results provide new insight into the mechanism and role of TDG sumoylation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Procedures for bacterial expression and purification of the numerous proteins used in this work have been described previously, including human E1-activating enzyme (SAE1/UBA2) (33), human E2-conjugating enzyme (Ubc9) (34), mature forms of human SUMO-1 (34) and SUMO-2 (35), human TDG (36), and a construct of mouse Ran GTPase-activating protein (RanGAP1) containing residues 420–589 (RanGAP1-NΔ419) (33). TDG modified with SUMO-1 (TDG∼SUMO-1) was produced in Escherichia coli by co-transforming cells with a plasmid for human TDG (36) and a plasmid for expressing human SUMO-1 (mature), E1, and E2 (37), and purifying TDG∼SUMO-1 as described for unmodified TDG (36). The proteins were purified to homogeneity as judged by SDS-PAGE, flash frozen, and stored at −80 °C. Protein concentration was determined by UV absorbance (20) for E1, E2, SUMO-1, TDG, and TDG∼SUMO-1, a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) for RanGAP1-NΔ419, or by SDS-PAGE (Coomassie staining) versus a BSA standard for SUMO-2.

Duplex DNA containing a 5-fluorouracil-guanine (5FU·G) mispair and nonspecific DNA (no mismatch) was prepared from purified synthetic 28-mer (Keck Biotechnology Resource Laboratory, Yale University) and 60-mer oligodeoxynucleotides (Integrated DNA Technologies), as described previously (16, 38).

In Vitro Sumoylation Assays

The assays were carried out in sumoylation assay buffer A (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.3, 110 mm potassium acetate, 2 mm magnesium acetate, 1 mm EGTA) with 0.1 μm E1, 1 μm E2, 10 μm SUMO-1 or SUMO-2, and 2 μm target protein (TDG or RanGAP1-NΔ419). The reactions were performed at room temperature (22 °C) or 37 °C and were initiated by the addition of ATP (final concentration of 2.5 mm). To monitor reaction progress, 8-μl samples were removed at selected time points, mixed with 2 μl of 5× SDS-PAGE sample buffer and incubated at 90 °C for 3 min (34), and analyzed by SDS-PAGE using precast Novex 10% Tris-glycine gels (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 100 V. Gels were stained with GelCode Blue Safe Protein Stain (Thermo Scientific) for 1 h, destained, and imaged using a Kodak EDAS 290 (Kodak Scientific Imaging Systems). The images shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Assays using HeLa nuclear extract contained 5 μl of 4× buffer A, 15 μg (7.5 μl) of HeLa nuclear extract (Millipore) or 7.5 μl of H2O (for reactions without extract), 0.1 μm E1, 0.5 μm E2, 0.8 μm TDG, and 5 μm SUMO-1 in a 20-μl reaction volume. Where indicated, reactions contained 5 μm SUMO-2 aldehyde (S2A) as a protease inhibitor. Reactions were performed at 30 °C and were initiated with addition of ATP (final concentration of 10 mm). Samples were removed at selected time points, diluted 10-fold into 1× buffer A, mixed with 5× SDS-PAGE sample buffer, and incubated at 90 °C for 3 min. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 10% Tris-glycine gels as described above. Immunoblotting was performed after transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes containing modified and unmodified TDG were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with anti-His6 mouse monoclonal antibody (Clontech). Membranes were then washed and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with Cy3-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (GE Healthcare). After drying, membranes were scanned at 532 nm using a Typhoon FLA 9500 scanner, and images were processed and analyzed using ImageQuant TL (GE Healthcare). The enzyme-product complex was prepared by incubating TDG (11.8 μm) with a 1.25 molar excess of 28-mer or 60-mer DNA containing a 5FU·G mispair (14.8 μm) for 2 h at room temperature. This yielded TDG that was fully saturated with AP-DNA product, given the rapid excision of 5FU by TDG (kmax = 6 s−1) (39) and very high affinity of TDG for AP-DNA (Kd <1 nm) (15, 20). A complex of TDG and nonspecific DNA (NS-DNA) was prepared by incubating TDG (11.2 μm) with a 2-fold molar excess of NS-DNA 28-mer or 60-mer (22.8 μm). This yielded TDG saturated with NS-DNA, given the binding affinity of Kd = ∼0.2 μm (20).

In Vitro Sumoylation Using Preformed E2-SUMO Thioesters

To monitor the E2-mediated conjugation step directly, sumoylation reactions were initiated with a preformed E2∼SUMO thioester. The E2∼SUMO thioesters were generated by adding ATP (10 μm final concentration) to buffer B (see below) containing 0.1 μm E1, 1.0 μm E2, and 1.0 μm SUMO-1, and incubating for 15 min at 37 °C. Then, a sample (3 μl) from this reaction was diluted 10-fold into buffer C containing TDG (varying concentrations). Reactions were run for up to 15 min at room temperature. To monitor reaction progress, 4-μl samples were removed at selected time points, mixed with 2× sample buffer containing 4 m urea, incubated 10 min at 37 °C (40), and analyzed by SDS-PAGE using precast 10% Tris-glycine gels (Novex) run for 1 h at 100 V. Buffer B contained 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.1% Tween 20. Buffer C is identical to buffer B except that MgCl2 is replaced with 5 mm EDTA. The complexes of TDG with AP-DNA and NS-DNA were prepared as described above.

Immunoblotting was performed after transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes containing SUMO-1 conjugates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with anti-SUMO-1 mouse monoclonal antibody 21C7 (Invitrogen). Membranes were then washed and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with Cy3-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (GE Healthcare). After drying, membranes were scanned and analyzed as described above.

The data were analyzed by measuring fluorescence intensity of TDG∼SUMO formation and disappearance of E2∼SUMO thioester. Time points of a given experiment where TDG∼SUMO intensity appeared to reach a maximum but E2∼SUMO was no longer measurable were treated as complete, and TDG∼SUMO fluorescence intensity was averaged for those time points to obtain a 100% complete value. Fluorescence intensities of all earlier times points were then divided by the averaged intensity of the completed time points to obtain a percentage of completed TDG∼SUMO formation. Only data points that fell along a linear range of TDG∼SUMO formation were used to determine the kobs values. The images and data are representative of at least three independent experiments. Kinetic parameters were derived using GraFit 5 (Erithacus Software).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays

Creation of AP-DNA using human uracil DNA glycosylase was performed as described (20) using the 28-bp DNA described above with a 3′ 6-FAM tag on the uracil-containing strand. Modification reactions were carried out overnight at room temperature as above, with 0.5 μm E2. AP-DNA was diluted (20 nm) in binding buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 5% glycerol, 1 mm DTT). TDG or TDG∼SUMO-1 was mixed with AP-DNA in binding buffer to give a final DNA concentration of 10 nm and protein concentrations of 5–500 nm. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min, loaded onto a 6% native polyacrylamide gel, and run for 60 min, 100 V at 4 °C. Gels were imaged using a Typhoon FLA 9500 (GE Healthcare) as described previously (41).

RESULTS

In Vitro Sumoylation of TDG and RanGAP1

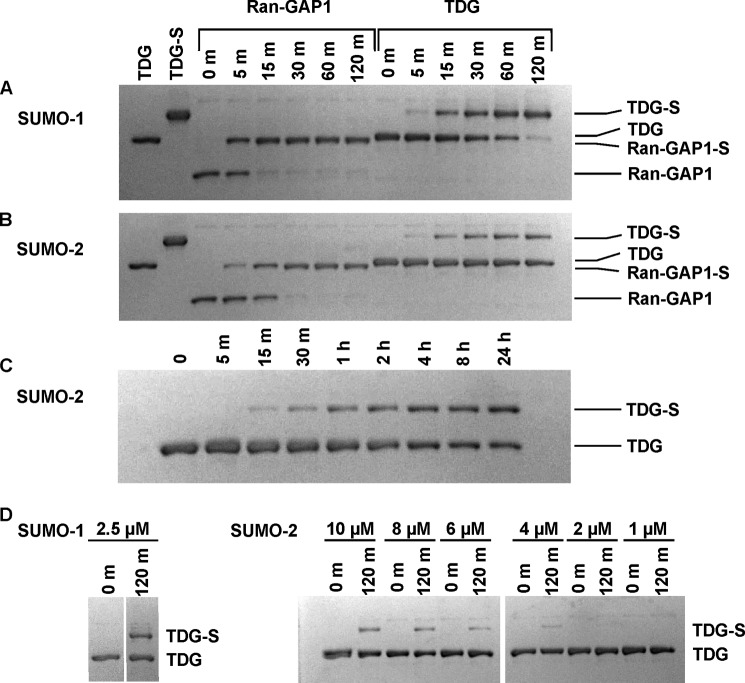

Although previous studies show that TDG can be sumoylated in vitro using purified proteins (E1, E2, SUMO-1) (13, 42), the kinetics of sumoylation, the relative efficiency of SUMO-1 versus SUMO-2/3 modification, and the specificity for free versus product-bound TDG were not addressed. Fig. 2A shows the results for SUMO-1 modification of TDG, and for comparison, RanGAP1, an established SUMO target for which in vitro modification has been well characterized (26, 27, 43). Both targets were efficiently modified by SUMO-1 at room temperature (22 °C); RanGAP1 was almost fully modified in 15 min, whereas complete modification of TDG took approximately 120 min. Both targets were modified more slowly by SUMO-2 relative to SUMO-1, and modification by SUMO-2 was slower for TDG versus RanGAP1 (Fig. 2B). Whereas RanGAP1 was fully modified by SUMO-2 in 30 min, TDG was only partially modified (∼30%) in 120 min. Moreover, TDG was only approximately 50% modified by SUMO-2 after a 24-h incubation period at room temperature (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Sumoylation of RanGAP1 and TDG at 22 °C. A and B, in vitro sumoylation experiments performed for modification of RanGAP1-NΔ419 and TDG by SUMO-1 (A) or SUMO-2 (B) and monitored by electrophoresis. The first lane of each gel contains pure TDG, and the second lane contains pure SUMO-1-modified TDG (TDG∼SUMO-1 or TDG-S). Reactions were initiated by adding ATP (2.5 mm) to buffer containing E1 (0.1 μm), E2 (1 μm), SUMO-1 or SUMO-2 (10 μm), and either RanGAP1-NΔ419 or TDG (2 μm). C, in vitro sumoylation of TDG with SUMO-2 over a 24-h time course. Samples were extracted at the time points given. D, in vitro sumoylation of TDG with SUMO-1 and SUMO-2 using SUMO concentrations of <10 μm. SUMO concentrations for a given assay are listed above each set of time points. Samples were extracted from the reaction and quenched at the indicated times (given in minutes), and the reaction progress was analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions.

We also examined the effect of varying the concentration of reaction components. We found that doubling the concentration of E1 or E2 (to 0.2 and 2 μm, respectively) does not increase the rate of TDG sumoylation by SUMO-1 (data not shown). TDG was modified more slowly when the concentration of SUMO-1 or SUMO-2 was decreased, and the effect was far more pronounced for SUMO-2. The amount of TDG modified in 120 min was reduced from ∼100% to ∼30% as the SUMO-1 concentration decreased from 10 to 2.5 μm. However, no modification was detected in the same time frame for reactions using SUMO-2 concentrations of 2 μm or less (Fig. 2D).

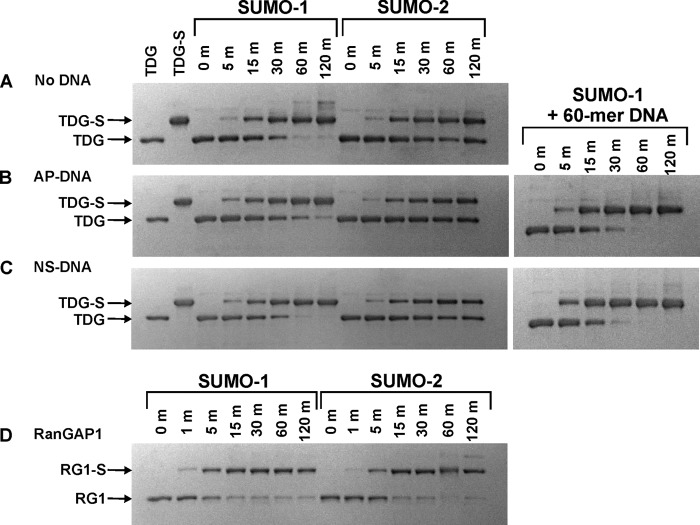

Sumoylation of TDG (and RanGAP1) by either SUMO-1 or SUMO-2 was substantially faster at 37 °C compared with 22 °C. This result is in part due to E2-mediated effects observed in previous studies (44). The time required for complete TDG modification by SUMO-1 was 60 min at 37 °C (Fig. 3A) compared with 120 min at 22 °C (Fig. 2A). In contrast to findings at 22 °C, the fraction of TDG modified in 15 min was similar for SUMO-1 and SUMO-2 (Fig. 3A). However, as seen at room temperature, TDG was not fully modified by SUMO-2 at 37 °C. Indeed, after 60 min, the reaction with SUMO-2 was ∼50% complete compared with 100% complete for SUMO-1 (Fig. 3A). Thus, modification of TDG by SUMO-2 was efficient to a point, but full modification was suppressed by a mechanism that is presently unclear. By comparison, we found that sumoylation of RanGAP1 was complete in <15 min with either SUMO-1 or SUMO-2 at 37 °C (Fig. 3D), consistent with previous studies (34, 35, 45). Modification by SUMO-1 was approximately 6-fold faster for RanGAP1 relative to TDG (compare Fig. 3, A and D).

FIGURE 3.

Sumoylation of TDG at 37 °C in the presence and absence of DNA. A–C, in vitro sumoylation reactions for modification of TDG by SUMO-1 or SUMO-2 performed at 37 °C in the absence of DNA (A) or in the presence of abasic DNA (B) or nonspecific (undamaged) DNA (C), and monitored by electrophoresis. The first lane of each gel contains pure TDG, and the second lane contains pure SUMO-1-modified TDG (TDG∼SUMO-1 or TDG-S). The sumoylation reactions were initiated by adding ATP (2.5 mm) to buffer containing E1 (0.1 μm), E2 (1 μm), SUMO-1 or SUMO-2 (10 μm), TDG (2 μm), with no DNA or with abasic DNA (2.5 μm) or nonspecific DNA (4.1 μm). D, in vitro sumoylation of RanGAP1-NΔ419 at 37 °C. Samples were extracted from the reaction and quenched at the indicated times (given in minutes), and the reaction progress was analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions.

In Vitro Sumoylation of TDG Bound to Abasic or Undamaged DNA

We sought to test the proposal that TDG is selectively sumoylated when it is bound to abasic DNA, i.e. in an enzyme-product complex. This model would predict faster sumoylation of TDG when it is bound to AP-DNA. In contrast, we found that modification by SUMO-1 or SUMO-2 was no faster for TDG in the enzyme-product complex (Fig. 3B) than free TDG (Fig. 3A). We also asked whether sumoylation rates are impacted by the binding of TDG to undamaged or nonspecific DNA (NS-DNA), given that TDG binds relatively tightly to NS-DNA (Kd = ∼0.2 μm) (20, 21) and could potentially reside largely on undamaged DNA in vivo. As shown in Fig. 3C, modification of TDG by SUMO-1 or SUMO-2 was not altered by the presence of a saturating concentration of NS-DNA. TDG sumoylation was slightly faster in the presence of 60 bp relative to 28 bp DNA, be it abasic or undamaged DNA (Fig. 3, B and C, right panels) and in the presence of plasmid relative to 28 bp DNA (not shown). Similar findings were reported for PARP-1, another DNA repair enzyme (46).

Notably, control reactions showed that sumoylation of RanGAP1 is not affected by the presence of AP-DNA or NS-DNA at the same concentrations used for TDG modification (data not shown), indicating that the DNA does not impact any step of the in vitro sumoylation reactions leading to formation of the E2∼SUMO thioester. Thus, our findings indicate that the E2∼SUMO thioesters are not specific for modifying TDG in an enzyme-product complex (16).

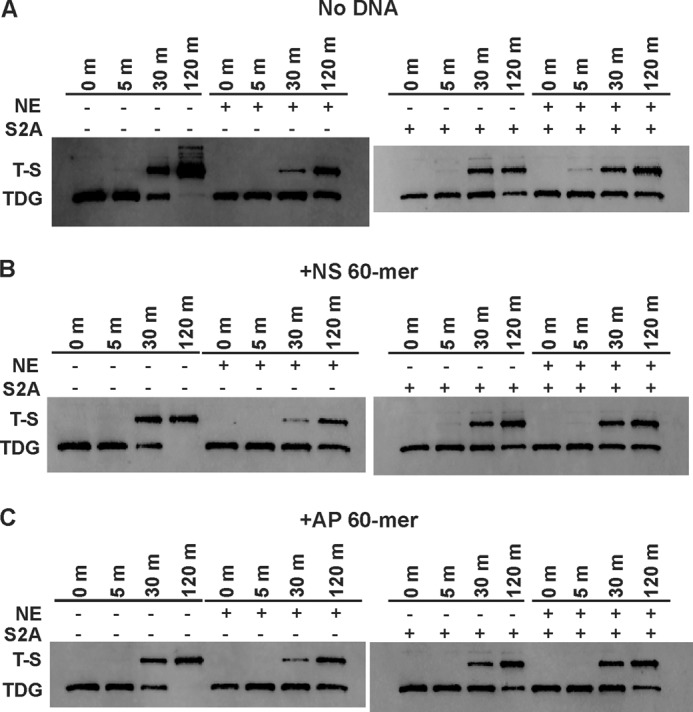

Given the previous report that AP-DNA stimulates the modification of recombinant TDG by HeLa nuclear extracts (NE) (16), we sought to examine the effect of HeLa NE using our in vitro assay. We found that the addition of HeLa NE slowed sumoylation of DNA-free TDG (Fig. 4, left), as well as TDG bound to nonspecific DNA (Fig. 4B, left) or abasic DNA (Fig. 4C, left), due potentially to sumoylation of other proteins in the NE or desumoylation of TDG by a SUMO-specific protease (SENP) in the NE. Consistent with the latter possibility, TDG modification in the presence of NE was modestly enhanced by the addition of S2A, a specific inhibitor of SENPs (Fig. 4, A–C, right panels) (47). S2A modestly slowed the reactions collected without NE, presumably by inhibiting E1 activity given that S2A is nearly identical to SUMO-2 and was used at the same concentration as SUMO for these reactions. Although additional studies are warranted, we found no evidence that a component of HeLa NE enhanced TDG modification or conferred specificity for modifying TDG when it is bound to AP-DNA.

FIGURE 4.

Sumoylation of free and DNA-bound TDG in the presence and absence of HeLa nuclear extract. A–C, immunoblot analysis of TDG modification in the presence and absence of nuclear extract for free TDG (A), TDG bound to nonspecific DNA (B), and TDG bound to AP-DNA (C). Reactions were performed in sumoylation buffer A with 0.1 μm E1, 0.5 μm E2, 0.8 μm TDG, and 5 μm SUMO-1 and were initiated by the addition of 10 mm ATP. As indicated, some reactions contained 15 μg of HeLa NE and/or 5 μm S2A (a SENP inhibitor). Samples were extracted from the reaction at the indicated time points, diluted 10-fold into buffer A, and quenched with 5×sample buffer before separation via SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. TDG was detected via immunoblotting with anti-His antibody and a fluorescent secondary antibody.

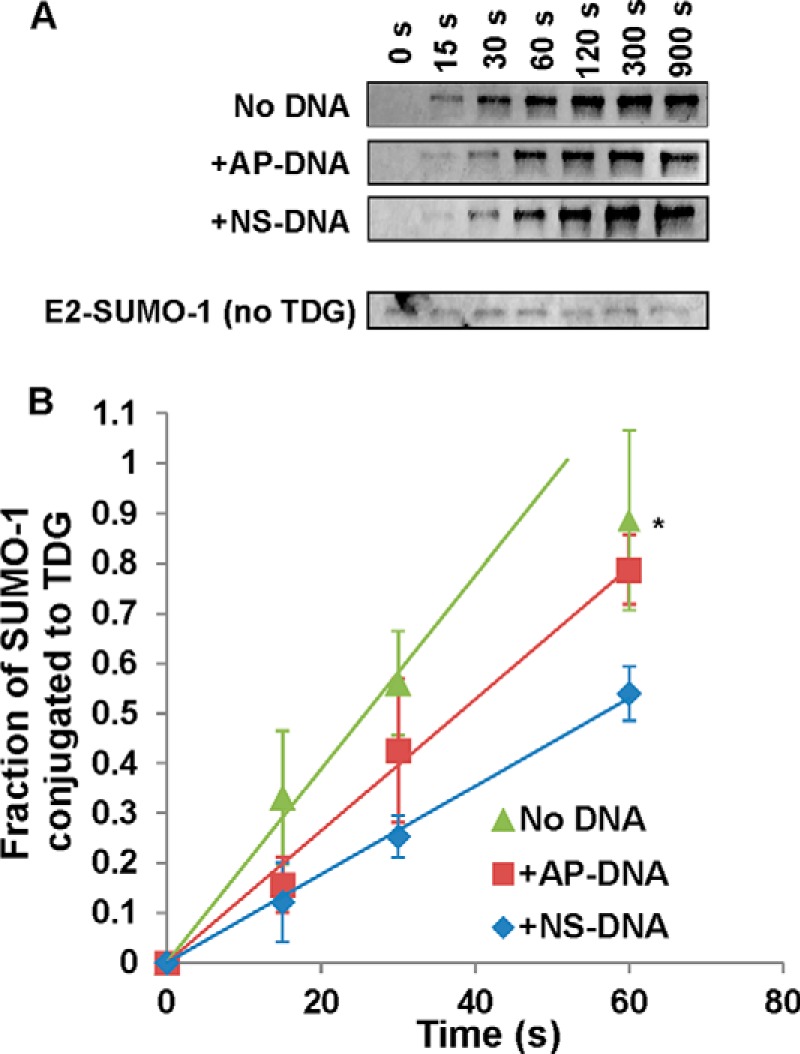

Sumoylation of Free and DNA-bound TDG by E2∼SUMO

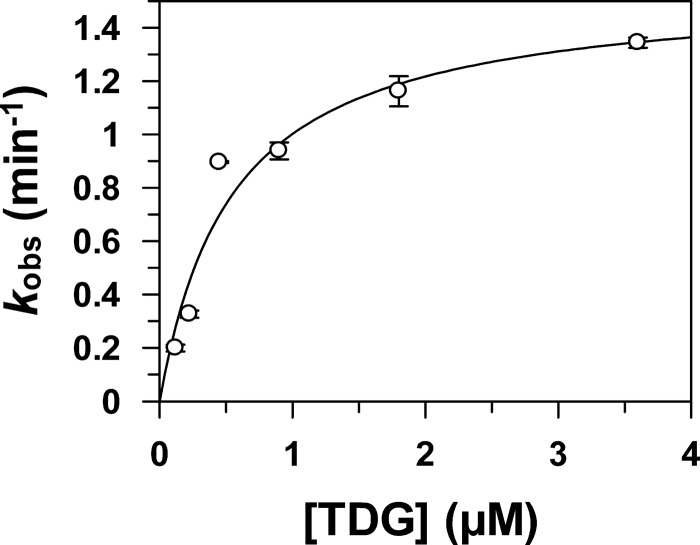

Given that the rates of the multiple-turnover reactions above could be influenced by multiple steps of two enzymatic reactions or the concentration of free SUMO, we sought to monitor the conjugation step directly, i.e. modification of TDG by the E2∼SUMO thioester. We followed a previously reported protocol to generate the E2∼SUMO thioester (45, 48), using a 2-fold longer incubation time to maximize the yield of E2∼SUMO and minimize the amount of free SUMO. A sample from this reaction was then diluted 10-fold into reaction buffer containing TDG (2 μm), giving a maximum initial E2∼SUMO-1 concentration of ∼0.1 μm and 1.8 μm unmodified TDG. As shown in Fig. 5A, modification of TDG by the E2∼SUMO-1 was quite rapid, with the reaction reaching completion in about 60 s at 22 °C. Modification by E2∼SUMO-1 was somewhat slower when TDG was bound to AP-DNA or NS-DNA (Fig. 5A). This finding is more clearly illustrated by fitting the data by linear regression (Fig. 5B), which gives rate constants of kobs = 1.1 ± 0.01 min−1 for free TDG, kobs = 0.78 ± 0.03 min−1 for TDG bound to AP-DNA, and kobs = 0.53 ± 0.06 min−1 for TDG bound to NS-DNA.

FIGURE 5.

Single-turnover assays of TDG modification by preloaded E2∼SUMO-1. A, immunoblot analysis of TDG modification by preformed E2∼SUMO-1 in the presence or absence of DNA. Preformed E2∼SUMO-1 conjugate was generated by adding ATP (10 μm) to buffer containing E1 (0.1 μm), E2 (1 μm), and SUMO-1 (1 μm). Reactions were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. Then, TDG modification reactions were initiated by adding 3 μl of the E2∼SUMO-1 reaction to 27 μl of buffer containing TDG (2 μm) and EDTA (5 mm). Samples were extracted from the reaction and quenched at the indicated times (given in seconds), and the formation of TDG∼SUMO-1 was analyzed by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions. Detection of SUMO-1 conjugates was performed via immunoblotting with anti-SUMO-1 primary antibody, followed by blotting with a fluorescent secondary antibody. B, kinetics for modification of TDG by preformed E2∼SUMO-1 in the presence or absence of DNA. Linear regression analysis provides initial rate constants of kobs = 1.1 min−1 (no DNA), 0.78 min−1 (AP-DNA), and 0.53 min−1 (NS-DNA). Error bars represent 1 S.D. The asterisk indicates the 60-s time point for free TDG, which was not used in data fitting.

As expected, the formation of TDG∼SUMO-1 was accompanied by the concomitant disappearance of E2∼SUMO-1 (data not shown). In addition, control reactions performed by diluting E2∼SUMO-1 into buffer lacking TDG showed that the thioester persisted for 15 min (Fig. 5A), indicating that its disappearance in the reactions with TDG is due to modification of TDG rather than spontaneous decay of the thioester, consistent with previous studies (49).

Dependence of Sumoylation Rate on TDG Concentration

To better understand the efficiency of TDG modification by E2∼SUMO thioesters, we examined the effect of varying the TDG concentration on the rate of sumoylation (kobs). As shown in Fig. 6, fitting the dependence of kobs on TDG concentration to a hyperbolic equation gives a maximal rate constant of kmax = 1.55 ± 0.16 min−1 and K1/2 = 0.55 ± 0.17 μm, indicating that E2∼SUMO-1 has substantial affinity for TDG. By comparison, other SUMO targets are modified faster but have lower affinity for E2∼SUMO-1, including RanGAP1 (kmax = 40 ± 9 min−1 and K1/2 = 2.9 ± 1.0 μm), a p53 peptide containing its sumoylation motif (kmax = 1.3 ± 0.1 min−1 and K1/2 = 40 ± 6 μm) (45), and phosphorylated myocyte-enhancement factor 2 (pMEF2) (kmax = 3.2 ± 0.1 min−1 and K1/2 = 240 ± 30 μm) (50).

FIGURE 6.

Dependence of modification rate on TDG concentration. Immunoblot analysis of TDG modification by preformed E2∼SUMO-1 was performed in the absence of DNA at TDG concentrations of 0.12 μm, 0.23 μm, 0.45 μm, 0.90 μm, 1.8 μm, and 3.6 μm. The kobs values were obtained by linear regression analysis of at least three time points per experiment. Error bars represent 1 S.D. Where error bars are not visible, they are smaller than the symbols. Data were fitted to a hyperbolic equation, kobs = kmax[TDG]/(K1/2 + [TDG]). The fitting yields kmax = 1.55 ± 0.16 min−1 and K1/2 = 0.55 ± 0.17 μm.

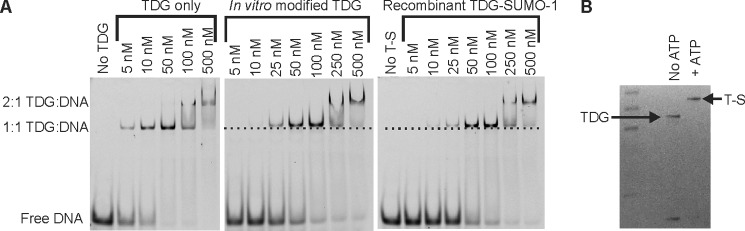

Effect of Sumoylation on DNA Binding by TDG

We examined the effect of SUMO-1 modification on the binding of TDG to abasic DNA, using TDG∼SUMO-1 produced with the in vitro reactions described above and recombinant TDG∼SUMO-1 produced using an in vivo sumoylation system in E. coli. Unmodified TDG (Fig. 7A, left) possesses high affinity for AP-DNA as reported previously (20). As expected, TDG that is fully modified by SUMO-1 using the in vitro reaction (Fig. 7B) exhibited much weaker affinity for AP-DNA (Fig. 7A, center), as did recombinant TDG∼SUMO-1 (Fig. 7A, right). However, TDG∼SUMO-1 still bound fairly tightly to AP-DNA, with a Kd of ∼50 nm, in contrast to previous reports that SUMO-modified TDG has little or no detectable affinity for AP-DNA (16, 17).

FIGURE 7.

EMSA analysis of AP-DNA binding by unmodified TDG and TDG∼SUMO-1. A, electrophoretic mobility assays (EMSAs) performed with 10 nm AP-DNA and varying concentrations (5–500 nm) of unmodified TDG (left panel), in vitro modified TDG (center panel), and recombinant TDG∼SUMO-1 (right panel). The dotted line below the TDG∼SUMO-1 lanes aligns with the midpoint of TDG-bound DNA in a 1:1 complex, indicating a slight, but clear, reduction in mobility for DNA bound to TDG∼SUMO-1 compared with unmodified TDG. B, SDS-PAGE analysis of an overnight in vitro sumoylation reaction performed to obtain the 100% modified TDG∼SUMO-1 used in the EMSA shown in A, center panel.

DISCUSSION

TDG Modification by SUMO-1 and SUMO-2

Given that mammalian cells have been shown to contain TDG modified by SUMO-1 and by SUMO-2/3 (16), we investigated the efficiency and specificity of sumoylation by the two SUMO paralogs using multiple turnover assays with purified E1 and E2 enzymes. Whereas modification of TDG was faster for SUMO-1 versus SUMO-2 at 22 °C (Fig. 2), initial modification rates were the same at 37 °C (Fig. 3A, up to 15 min). Likewise, RanGAP1 was modified faster by SUMO-1 versus SUMO-2 at 22 °C, but modification at 37 °C proceeded at about the same rate for either paralog. Perhaps the most remarkable finding regarding paralog specificity was that TDG was modified to a maximum level of ∼50% by SUMO-2, regardless of temperature or reaction time, whereas it was fully (100%) modified by SUMO-1. Notably, under our reaction conditions, RanGAP1 was completely modified by either SUMO paralog, at rates that were comparable with one another and agreed with previous findings (34, 35, 45). Additional studies are warranted to explore the mechanism and potential biological relevance of our findings regarding SUMO-2 modification of TDG.

SUMO Modification of DNA-bound TDG

To examine the proposal that sumoylation was specific for product-bound TDG, we compared the modification rates for free TDG and TDG bound to a saturating concentration of undamaged DNA or AP-DNA. Using a multiple turnover assay with E1 and E2 enzymes, the sumoylation rates were the same for free and DNA-bound TDG (Fig. 3). Sumoylation of TDG by preformed E2∼SUMO-1 thioester was slower when TDG was bound to AP-DNA or NS-DNA (Fig. 5). Thus, we found no evidence that the E2-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 has inherent specificity for sumoylating DNA-bound TDG. Notably, recent studies find that, although Ubc9 does not bind DNA, Ubc9-mediated sumoylation of PARP-1 is enhanced when PARP-1 binds undamaged but not damaged DNA, due presumably to a conformational change in PARP-1 that is unique to undamaged DNA and recognized by Ubc9 (46). However, our results indicated that if specificity for product-bound TDG occurs in vivo, as has been proposed (16), it likely requires additional factors, which may include an E3 ligase. Notably, the SUMO ligase Siz2 is required for DNA damage-induced sumoylation of homologous recombination proteins, as needed for repair of double strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (51). This requires localization of Siz2 on DNA via a stress-activated protein domain. Additional studies are needed to determine whether an E3 ligase could provide specificity for sumoylating product-bound TDG.

Together, the results here and previous findings suggest that the SUMO modification site is not blocked when TDG binds to DNA. Previous studies show that SUMO motifs typically reside in a disordered region of the target protein, consistent with findings that they adopt an extended conformation when bound to Ubc9 (43). The sumoylation motif of TDG (329VKEE332; human) is located in its C-terminal region, which lies outside the catalytic domain (Fig. 1) and is disordered (52).3 This could account for findings here that modification is not substantially hindered when TDG is bound in a tight and slow dissociating product complex with abasic DNA (11–15).

Efficient Sumoylation of TDG by Ubc9

Whereas ubiquitin E2-conjugating enzymes typically require an E3 ligase for specificity, the SUMO E2 can conjugate some targets in the absence of an E3 ligase (43). Our results provide the first evidence that TDG can be modified efficiently by Ubc9 in vitro without an E3 ligase. We show that sumoylation by E2∼SUMO-1 is efficient for TDG relative to other SUMO targets; kmax/K1/2 is 3 μm−1·min−1 for TDG (Fig. 6), 14 μm−1·min−1 for RanGAP1, 0.033 μm−1·min−1 for p53 (peptide) (45), and 0.013 μm−1·min−1 for pMEF2 (50). Given that Ubc9 contacts regions of RanGAP1 in addition to the four-residue sumoylation motif (53), our observation that Ubc9∼SUMO-1 has relatively high affinity for TDG suggests that Ubc9 (or Ubc9∼SUMO-1) could make additional contact with TDG in a similar manner. Although our results indicate that E2∼SUMO modifies TDG efficiently relative to other SUMO targets in vitro, they do not exclude the possibility that sumoylation of TDG in vivo involves an E3 ligase, which could potentially facilitate association of E2∼SUMO and TDG, among other potential functions.

TDG∼SUMO-1 Displays Weakened yet Significant Affinity for AP-DNA

Contrary to previous reports (16, 17), we showed that TDG∼SUMO-1 binds relatively tightly to AP-DNA (Kd = ∼50 nm, Fig. 7). Nevertheless, sumoylation weakens the binding affinity of TDG for AP-DNA such that dissociation (koff) of the enzyme-product complex is likely faster for TDG∼SUMO relative to unmodified TDG, in keeping with the idea that sumoylation of product-bound TDG could potentially enhance enzymatic turnover. Our finding that TDG∼SUMO-1 retains substantial affinity for AP-DNA highlights the need for additional studies to determine the impact of sumoylation, by SUMO-1 and SUMO-2/3, on substrate binding and catalysis by TDG for its various DNA substrates.

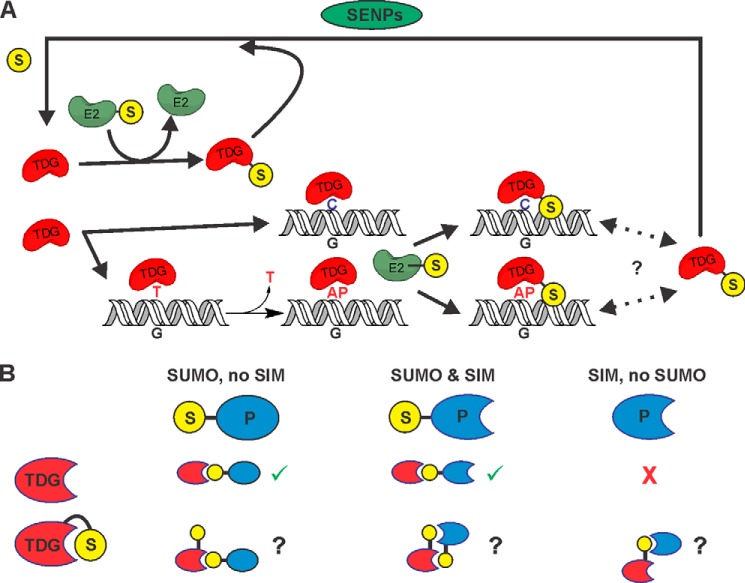

Biological Role(s) of TDG Sumoylation

Fig. 8 summarizes our results and previous findings regarding sumoylation of TDG. We found that E2∼SUMO can rapidly sumoylate free TDG and TDG bound to either abasic or undamaged DNA, showing that SUMO-charged E2 has no inherent specificity for product-bound TDG (Fig. 8A). Thus, selective modification of product-bound TDG, as proposed in a previous model (16), would require an E3 ligase or another specificity factor. However, our findings raise the possibility that specificity for sumoylating only product-bound TDG might not be required to stimulate product release. The E2-mediated modification of product-bound TDG (kobs = 0.8 min−1, Fig. 5B) is orders of magnitude faster than the product dissociation rate (koff) suggested by the very slow steady-state enzymatic turnover of TDG (kcat = 0.00034 min−1; G·T substrates) (12, 14), and sumoylation would likely trigger rapid product release (16, 17). Although product release (koff) is probably faster than enzymatic turnover (kcat) and may be enhanced by the follow-on base excision repair enzyme APE1 (AP endonuclease 1) (12, 14), koff for unmodified TDG could still be far slower than E2-mediated sumoylation. Thus, sumoylation of product-bound TDG, even in the absence of an E3 ligase, could potentially enhance enzymatic turnover, particularly for G·T substrates.

FIGURE 8.

Summary of findings from these and previous studies regarding TDG sumoylation. A, our results showed that E2∼SUMO efficiently modifies free and DNA-bound TDG, exhibiting no substantial specificity for product-bound TDG. Thus, the previous proposal that TDG is selectively sumoylated when it is bound to AP-DNA (just after base excision) would require an unidentified E3 or other selectivity factor (16). Nevertheless, modification of product-bound TDG by E2∼SUMO is relatively efficient and could potentially stimulate dissociation of the product complex (in the absence of an E3), thereby enhancing enzymatic turnover. Given our finding that TDG∼SUMO-1 still binds AP-DNA with high affinity, it is possible that TDG∼SUMO-1 shuttles on and off of AP-DNA (or undamaged DNA), rather than dissociating completely (as indicated by dotted lines and question mark). However, because TDG∼SUMO lacks G·T activity and E2 modifies free and DNA-bound TDG, efficient desumoylation (by SENPs) is needed to maintain a pool of catalytically active TDG. B, sumoylation of free TDG can modulate its interactions with other proteins (P), which can depend on whether they contain a SIM or are themselves sumoylated. Crystallographic studies (17, 18) indicate that for sumoylated TDG, the covalently tethered SUMO domain occupies its own SIM, which could potentially suppress interactions with a sumoylated partner protein, unless it also contains a SIM. Potential SUMO-mediated interactions of free and modified TDG with sumoylated and/or SIM-containing partners are shown. Checkmarks (in green) indicate allowed SUMO/SIM interactions, question marks indicate interactions that would require a change in SUMO conformation to occur, and crosses (in red) indicate SUMO/SIM-mediated interactions that should not occur.

Findings that sumoylated TDG has no activity for G·T mispairs (16) and greatly reduced activity for some other substrates4 indicate that efficient SENP-mediated removal of SUMO is needed to maintain a sufficient pool of unmodified TDG. Observations that TDG is largely unmodified in human cells (16), even as E2-mediated sumoylation is relatively efficient for free and DNA-bound TDG, indicate that SENPs can quickly desumoylate TDG, although this could also reflect unidentified factors that regulate sumoylation of TDG.

Of course, it is plausible that sumoylation of TDG serves purposes other than (or in addition to) regulating product release. Many proteins that interact with TDG are also SUMO targets and/or contain a SUMO-interacting motif (SIM), including p53 and p300, to name well studied examples (Fig. 8B) (42, 54–56). Sumoylation of TDG could potentially modulate interactions with other proteins in at least two ways. It could stabilize binding to targets that contain a SIM, a common function of protein sumoylation. For example, sumoylation of TDG enhances its affinity for promyelocytic leukemia protein (32). However, sumoylation of TDG could potentially hinder its interaction with other sumoylated proteins. Because the single SUMO modification site of TDG (Lys-330) flanks its canonical SIM (Val-308–Val-311), the covalently tethered SUMO domain can occupy the SIM of TDG (Fig. 8B), as indicated by crystal structures (Fig. 1) (17, 18). This could explain findings that sumoylation of TDG suppresses its binding to free SUMO (32) and hinders its association with (and acetylation by) p300 (42). TDG interacts with many additional proteins that function in transcriptional regulation, including the retinoic acid receptor, retinoid X receptor (57), estrogen receptor α (58), SRC1 (59), c-Jun (60), and TCF4 in the Wnt pathway (61). Notably, retinoid X receptor α, estrogen receptor α, and c-Jun are all targets for sumoylation (62–65). It is presently unclear whether these interactions might be enhanced by, perturbed by, or independent of TDG sumoylation. Further studies are needed to understand the potential role of sumoylation in regulating these protein interactions and the catalytic activity of TDG.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. F. Melchior (University of Heidelberg) for expression plasmids for Ubc9 and SUMO-1 (mature form), Prof. M. Shirakawa (Kyoto University) for a plasmid for the co-expression of human SUMO-1 and the E1 and E2 enzymes, and Dr. Bor-Jang Hwang and Dr. Aparna Kishor for assistance with immunoblotting. Support for procuring the imaging system (GE Typhoon FLA 9500) used in these studies was provided by the National Institutes of Health Grant S10-OD011969 (to A. L. Lu).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-GM72711 (to A. C. D.) and R01-GM060980 (to M. J. M.).

A. Maiti and A. C. Drohat, unpublished observations by NMR.

M. E. Fitzgerald and A. C. Drohat, unpublished observations.

- AP

- apurinic/apyrimidinic

- E1

- human SAE1/UBA2

- E2

- human UBC9

- 5FU

- 5-fluorouracil

- mC

- 5-methylcytosine

- NE

- nuclear extracts

- NS

- nonspecific

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- RanGAP1

- Ran GTPase-activating protein

- S2A

- SUMO-2 aldehyde

- SENP

- SUMO-specific protease

- SIM

- SUMO interacting motif

- SUMO

- small ubiquitin-like modifiers

- TDG

- thymine DNA glycosylase

- TET

- ten-eleven translocation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Neddermann P., Jiricny J. (1993) The purification of a mismatch-specific thymine-DNA glycosylase from HeLa cells. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 21218–21224 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neddermann P., Gallinari P., Lettieri T., Schmid D., Truong O., Hsuan J. J., Wiebauer K., Jiricny J. (1996) Cloning and expression of human G/T mismatch-specific thymine-DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 12767–12774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cortellino S., Xu J., Sannai M., Moore R., Caretti E., Cigliano A., Le Coz M., Devarajan K., Wessels A., Soprano D., Abramowitz L. K., Bartolomei M. S., Rambow F., Bassi M. R., Bruno T., Fanciulli M., Renner C., Klein-Szanto A. J., Matsumoto Y., Kobi D., Davidson I., Alberti C., Larue L., Bellacosa A. (2011) Thymine DNA glycosylase is essential for active DNA demethylation by linked deamination-base excision repair. Cell 146, 67–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cortázar D., Kunz C., Selfridge J., Lettieri T., Saito Y., MacDougall E., Wirz A., Schuermann D., Jacobs A. L., Siegrist F., Steinacher R., Jiricny J., Bird A., Schär P. (2011) Embryonic lethal phenotype reveals a function of TDG in maintaining epigenetic stability. Nature 470, 419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Maiti A., Drohat A. C. (2011) Thymine DNA glycosylase can rapidly excise 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine: potential implications for active demethylation of CpG sites. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 35334–35338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. He Y. F., Li B. Z., Li Z., Liu P., Wang Y., Tang Q., Ding J., Jia Y., Chen Z., Li L., Sun Y., Li X., Dai Q., Song C. X., Zhang K., He C., Xu G. L. (2011) Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science 333, 1303–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ito S., Shen L., Dai Q., Wu S. C., Collins L. B., Swenberg J. A., He C., Zhang Y. (2011) Tet proteins can convert 5-methylcytosine to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine. Science 333, 1300–1303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pfaffeneder T., Hackner B., Truss M., Münzel M., Müller M., Deiml C. A., Hagemeier C., Carell T. (2011) The discovery of 5-formylcytosine in embryonic stem cell DNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50, 7008–7012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Song C. X., Szulwach K. E., Dai Q., Fu Y., Mao S. Q., Lin L., Street C., Li Y., Poidevin M., Wu H., Gao J., Liu P., Li L., Xu G. L., Jin P., He C. (2013) Genome-wide profiling of 5-formylcytosine reveals its roles in epigenetic priming. Cell 153, 678–691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shen L., Wu H., Diep D., Yamaguchi S., D'Alessio A. C., Fung H. L., Zhang K., Zhang Y. (2013) Genome-wide analysis reveals TET- and TDG-dependent 5-methylcytosine oxidation dynamics. Cell 153, 692–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Waters T. R., Swann P. F. (1998) Kinetics of the action of thymine DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 20007–20014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Waters T. R., Gallinari P., Jiricny J., Swann P. F. (1999) Human thymine DNA glycosylase binds to apurinic sites in DNA but is displaced by human apurinic endonuclease 1. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Steinacher R., Schär P. (2005) Functionality of human thymine DNA glycosylase requires SUMO-regulated changes in protein conformation. Curr. Biol. 15, 616–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fitzgerald M. E., Drohat A. C. (2008) Coordinating the initial steps of base excision repair: apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 actively stimulates thymine DNA glycosylase by disrupting the product complex. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32680–32690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schärer O. D., Nash H. M., Jiricny J., Laval J., Verdine G. L. (1998) Specific binding of a designed pyrrolidine abasic site analog to multiple DNA glycosylases. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 8592–8597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hardeland U., Steinacher R., Jiricny J., Schär P. (2002) Modification of the human thymine-DNA glycosylase by ubiquitin-like proteins facilitates enzymatic turnover. EMBO J. 21, 1456–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baba D., Maita N., Jee J. G., Uchimura Y., Saitoh H., Sugasawa K., Hanaoka F., Tochio H., Hiroaki H., Shirakawa M. (2005) Crystal structure of thymine DNA glycosylase conjugated to SUMO-1. Nature 435, 979–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baba D., Maita N., Jee J. G., Uchimura Y., Saitoh H., Sugasawa K., Hanaoka F., Tochio H., Hiroaki H., Shirakawa M. (2006) Crystal structure of SUMO-3-modified thymine-DNA glycosylase. J. Mol. Biol. 359, 137–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schärer O. D., Kawate T., Gallinari P., Jiricny J., Verdine G. L. (1997) Investigation of the mechanisms of DNA binding of the human G/T glycosylase using designed inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 4878–4883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Morgan M. T., Maiti A., Fitzgerald M. E., Drohat A. C. (2011) Stoichiometry and affinity for thymine DNA glycosylase binding to specific and nonspecific DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 2319–2329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maiti A., Noon M. S., MacKerell A. D., Jr., Pozharski E., Drohat A. C. (2012) Lesion processing by a repair enzyme is severely curtailed by residues needed to prevent aberrant activity on undamaged DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 8091–8096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Johnson E. S. (2004) Protein modification by SUMO. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 355–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Geiss-Friedlander R., Melchior F. (2007) Concepts in sumoylation: a decade on. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 947–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sjolund A. B., Senejani A. G., Sweasy J. B. (2013) MBD4 and TDG: multifaceted DNA glycosylases with ever expanding biological roles. Mutat. Res. 743, 12–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pilla E., Möller U., Sauer G., Mattiroli F., Melchior F., Geiss-Friedlander R. (2012) A novel SUMO1-specific interacting motif in dipeptidyl peptidase 9 (DPP9) that is important for enzymatic regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 44320–44329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matunis M. J., Coutavas E., Blobel G. (1996) A novel ubiquitin-like modification modulates the partitioning of the Ran-GTPase-activating protein RanGAP1 between the cytosol and the nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 135, 1457–1470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mahajan R., Delphin C., Guan T., Gerace L., Melchior F. (1997) A small ubiquitin-related polypeptide involved in targeting RanGAP1 to nuclear pore complex protein RanBP2. Cell 88, 97–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bergink S., Jentsch S. (2009) Principles of ubiquitin and SUMO modifications in DNA repair. Nature 458, 461–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Flotho A., Melchior F. (2013) Sumoylation: a regulatory protein modification in health and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 82, 357–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu X. M., Yang F. F., Yuan Y. F., Zhai R., Huo L. J. (2013) SUMOylation of mouse p53b by SUMO-1 promotes its pro-apoptotic function in ovarian granulosa cells. PLoS One 8, e63680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31. Müller S., Matunis M. J., Dejean A. (1998) Conjugation with the ubiquitin-related modifier SUMO-1 regulates the partitioning of PML within the nucleus. EMBO J. 17, 61–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Takahashi H., Hatakeyama S., Saitoh H., Nakayama K. I. (2005) Noncovalent SUMO-1 binding activity of thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) is required for its SUMO-1 modification and colocalization with the promyelocytic leukemia protein. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 5611–5621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang H., Saitoh H., Matunis M. J. (2002) Enzymes of the SUMO modification pathway localize to filaments of the nuclear pore complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 6498–6508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Werner A., Moutty M. C., Möller U., Melchior F. (2009) Performing in vitro sumoylation reactions using recombinant enzymes. Methods Mol. Biol. 497, 187–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhu J., Zhu S., Guzzo C. M., Ellis N. A., Sung K. S., Choi C. Y., Matunis M. J. (2008) Small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) binding determines substrate recognition and paralog-selective SUMO modification. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29405–29415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morgan M. T., Bennett M. T., Drohat A. C. (2007) Excision of 5-halogenated uracils by human thymine DNA glycosylase: robust activity for DNA contexts other than CpG. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 27578–27586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Uchimura Y., Nakamura M., Sugasawa K., Nakao M., Saitoh H. (2004) Overproduction of eukaryotic SUMO-1- and SUMO-2-conjugated proteins in Escherichia coli. Anal. Biochem. 331, 204–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maiti A., Drohat A. C. (2011) Dependence of substrate binding and catalysis on pH, ionic strength, and temperature for thymine DNA glycosylase: insights into recognition and processing of G·T mispairs. DNA Repair 10, 545–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maiti A., Morgan M. T., Drohat A. C. (2009) Role of two strictly conserved residues in nucleotide flipping and N-glycosylic bond cleavage by human thymine DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 36680–36688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scheffner M., Huibregtse J. M., Howley P. M. (1994) Identification of a human ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme that mediates the E6-AP-dependent ubiquitination of p53. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 8797–8801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maiti A., Michelson A. Z., Armwood C. J., Lee J. K., Drohat A. C. (2013) Divergent mechanisms for enzymatic excision of 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine from DNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 15813–15822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mohan R. D., Rao A., Gagliardi J., Tini M. (2007) SUMO-1-dependent allosteric regulation of thymine DNA glycosylase alters subnuclear localization and CBP/p300 recruitment. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 229–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gareau J. R., Lima C. D. (2010) The SUMO pathway: emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation, and recognition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 861–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tatham M. H., Kim S., Yu B., Jaffray E., Song J., Zheng J., Rodriguez M. S., Hay R. T., Chen Y. (2003) Role of an N-terminal site of Ubc9 in SUMO-1, -2, and -3 binding and conjugation. Biochemistry 42, 9959–9969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yunus A. A., Lima C. D. (2006) Lysine activation and functional analysis of E2-mediated conjugation in the SUMO pathway. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 491–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zilio N., Williamson C. T., Eustermann S., Shah R., West S. C., Neuhaus D., Ulrich H. D. (2013) DNA-dependent SUMO modification of PARP-1. DNA Repair 12, 761–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hickey C. M., Wilson N. R., Hochstrasser M. (2012) Function and regulation of SUMO proteases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 755–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yunus A. A., Lima C. D. (2009) Purification of SUMO-conjugating enzymes and kinetic analysis of substrate conjugation. Methods Mol. Biol. 497, 167–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yunus A. A., Lima C. D. (2005) Purification and activity assays for Ubc9, the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme for the small ubiquitin-like modifier SUMO. Methods Enzymol. 398, 74–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mohideen F., Capili A. D., Bilimoria P. M., Yamada T., Bonni A., Lima C. D. (2009) A molecular basis for phosphorylation-dependent SUMO conjugation by the E2 UBC9. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 945–952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Psakhye I., Jentsch S. (2012) Protein group modification and synergy in the SUMO pathway as exemplified in DNA repair. Cell 151, 807–820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Smet-Nocca C., Wieruszeski J. M., Léger H., Eilebrecht S., Benecke A. (2011) SUMO-1 regulates the conformational dynamics of thymine-DNA glycosylase regulatory domain and competes with its DNA binding activity. BMC Biochem. 12, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bernier-Villamor V., Sampson D. A., Matunis M. J., Lima C. D. (2002) Structural basis for E2-mediated SUMO conjugation revealed by a complex between ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc9 and RanGAP1. Cell 108, 345–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim E. J., Um S. J. (2008) Thymine-DNA glycosylase interacts with and functions as a coactivator of p53 family proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 377, 838–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hock A., Vousden K. H. (2010) Regulation of the p53 pathway by ubiquitin and related proteins. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 42, 1618–1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Stindt M. H., Carter S., Vigneron A. M., Ryan K. M., Vousden K. H. (2011) MDM2 promotes SUMO-2/3 modification of p53 to modulate transcriptional activity. Cell Cycle 10, 3176–3188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Um S., Harbers M., Benecke A., Pierrat B., Losson R., Chambon P. (1998) Retinoic acid receptors interact physically and functionally with the T:G mismatch-specific thymine-DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 20728–20736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chen D., Lucey M. J., Phoenix F., Lopez-Garcia J., Hart S. M., Losson R., Buluwela L., Coombes R. C., Chambon P., Schär P., Ali S. (2003) T:G mismatch-specific thymine-DNA glycosylase potentiates transcription of estrogen-regulated genes through direct interaction with estrogen receptor α. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 38586–38592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lucey M. J., Chen D., Lopez-Garcia J., Hart S. M., Phoenix F., Al-Jehani R., Alao J. P., White R., Kindle K. B., Losson R., Chambon P., Parker M. G., Schär P., Heery D. M., Buluwela L., Ali S. (2005) T:G mismatch-specific thymine-DNA glycosylase (TDG) as a coregulator of transcription interacts with SRC1 family members through a novel tyrosine repeat motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 6393–6404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chevray P. M., Nathans D. (1992) Protein interaction cloning in yeast: identification of mammalian proteins that react with the leucine zipper of Jun. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 5789–5793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Xu X., Yu T., Shi J., Chen X., Zhang W., Lin T., Liu Z., Wang Y., Zeng Z., Wang C., Li M., Liu C. (2014) Thymine DNA glycosylase is a positive regulator of Wnt signaling in colorectal cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 13, 8881–8890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Choi S. J., Chung S. S., Rho E. J., Lee H. W., Lee M. H., Choi H. S., Seol J. H., Baek S. H., Bang O. S., Chung C. H. (2006) Negative modulation of RXRα transcriptional activity by small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) modification and its reversal by SUMO-specific protease SUSP1. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30669–30677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Muller S., Berger M., Lehembre F., Seeler J. S., Haupt Y., Dejean A. (2000) c-Jun and p53 activity is modulated by SUMO-1 modification. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 13321–13329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bossis G., Malnou C. E., Farras R., Andermarcher E., Hipskind R., Rodriguez M., Schmidt D., Muller S., Jariel-Encontre I., Piechaczyk M. (2005) Down-regulation of c-Fos/c-Jun AP-1 dimer activity by sumoylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 6964–6979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sentis S., Le Romancer M., Bianchin C., Rostan M. C., Corbo L. (2005) Sumoylation of the estrogen receptor α hinge region regulates its transcriptional activity. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 2671–2684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]