INTRODUCTION

In 2011, Morehouse School of Medicine convened a summit in San Juan, Puerto Rico, titled Triangulating on Health Equity: Best Practices in Integrating Health Promotion, Primary Care, and Social Determinants to Improve Community Health Outcomes. The primary goals of the summit were to (a) discuss health status and the underlying social determinants influencing health outcomes in the Caribbean; (b) produce recommendations that could effectively tackle complex interacting factors that hinder the improvement of health in the region; and (c) develop and cultivate formal networks of collaboration among regional minority institutions, investigators, and caregivers in the Caribbean, the United States, and Latin America.

This article summarizes the recommendations put forth at the summit. To that end, the article highlights the challenges and opportunities in the region as it moves to improve health outcomes with an integrative approach. To set the context of the summit, we begin with a brief background on the state of health in the Caribbean, highlighting health trends and the sociocultural factors, as related to, and having influence on, the region’s health outcomes.

HEALTH IN THE CARIBBEAN

Chronic and communicable diseases are devastating to individuals and community, threatening quality of life and becoming an increasingly consequential factor in the Caribbean’s development. Vulnerable populations such as the poor and underserved are more likely to develop chronic illness and be at risk for communicable diseases than any other group (1,2).

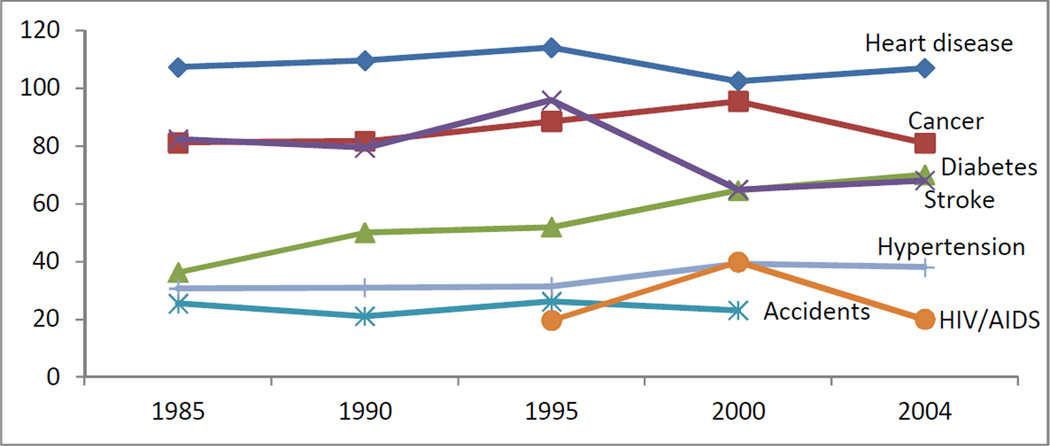

In the Western hemisphere, the epidemic of chronic disease has most affected the Caribbean region (3). The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) noted that “the Caribbean has the highest death rates from heart disease and the top five countries for diabetes in the Americas” (1, p14). Among the countries in the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), heart disease ranks as the leading cause of death (4,5). Other conditions such as cancer, stroke, diabetes, and HIV are among the leading causes of death. In 1995, AIDS related death was added as one of the leading causes of death in the region (5) and in 2005, it became the leading cause of death among adults ages 15–44 (6).

The unchanging trends in the leading causes of death overtime highlight the region’s health crisis (Figure 1). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 80% of heart disease and diabetes and 40% of cancers are preventable; another 30% of cancers are treatable (7). Chronic diseases were determined to be the primary causes of potential years of life lost (PYLL) before age 65 among CARICOM countries (1). The same report noted a 25% decline in PYLL due to AIDS-related illnesses resulting from the expansion of antiretroviral treatment beginning in 2004 (1). Unlike other regions, Caribbean nations experience a significant number of deaths resulting from accidents and homicides (Table 1). Between 2000 and 2004, PYLL in the Caribbean increased by 27% as a result of the rise in violence and accidents (1).

Figure 1. Crude mortality rate (per 100,000 population) by year: CAREC member states (5).

Table 1.

| Caribbean | World | High income countries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cause of death | % | Cause of death | % | Cause of death | % | |

| 1. | Heart disease | 15.7 | Heart disease | 12.8 | Heart disease | 15.6 |

| 2. | Cancer | 14.6 | Stroke | 10.8 | Stroke | 8.7 |

| 3. | Stroke | 10 | Respiratory infections | 6.1 | Trachea, bronchus, lung cancer | 5.9 |

| 4. | Diabetes | 10 | Pulmonary disease | 5.8 | Alzheimer’s disease | 4.1 |

| 5. | HIV/AIDS | 6 | Diarrheal diseases | 4.3 | Respiratory infections | 3.8 |

| 6. | Hypertensive diseases | 6 | HIV/AIDS | 3.1 | Pulmonary disease | 3.5 |

| 7. | Accidents | 4 | Trachea, bronchus, lung cancer | 2.4 | Colon and rectum cancer | 3.3 |

| 8. | Homicide | 3 | Tuberculosis | 2.4 | Diabetes | 2.6 |

| 9. | Respiratory infections | 2 | Diabetes | 2.2 | Hypertensive diseases | 2.3 |

| 10. | Respiratory diseases | 2 | Traffic accidents | 2.1 | Breast cancer | 1.9 |

The reported statistics “help dispel the myth that chronic diseases are mainly a problem of the elderly” (1, p15). The data challenges the perception that non-communicable diseases (NCD) are more concentrated in high-income countries; trends in the Caribbean point to an increase of NCD in low and middle income countries. Without effective comprehensive approaches, the associated health related cost of addressing these conditions may drive individuals and governments further into poverty (8).

Caribbean nations have launched responses to unfavorable health trends. Across the region, there have been successful initiatives to improve the quality of life and to facilitate the adoption of integrative approaches to improve health outcomes. A recent report identified the impact of government policies aimed at emphasizing sanitation, nutrition, and primary health care to improve the health status of people in the Caribbean (9). The report credited the implementation of public health interventions and practices for the dramatic reduction in infant mortality rates (9). There have also been initiatives targeting health risk behaviors and social determinants of health in the region. In 2007, Heads of State of Caribbean nations convened the Summit on Non-Communicable Diseases to address, for the first time, the combined epidemics (i.e. Cardiovascular illness, Diabetes, Cancer) in the region (1).

Country-specific achievements underscore the important strides made toward improving health outcomes. In 2010, Barbados joined the ranks of “developed” nations according to the United Nations Human Development Index. This distinction showcases Barbados’ high quality of life indices, a privilege-status correlated to “outspending all of its Caribbean neighbours when it comes to providing health care for each resident and it has one of the lowest murder rates in the Caribbean and Latin America” (10, p1).

Despite these achievements, profound gaps in access to care remain, affecting the wellbeing of the Caribbean people (11,12). Certainly, the efforts and remarkable successes documented in the region are tempered by the immensity of the task at hand. As it is often the case, region-specific sociocultural and economic factors contribute to health outcomes and present significant challenges to addressing the region’s health status, alongside opportunities to meet these challenges.

Sociocultural determinants of health

The impact of the Caribbean’s history and diversity cannot be minimized in this discussion. The Caribbean is very unique, differing considerably from other regions in the Western hemisphere (13). The region is composed of approximately 42 million people living in nation-islands that extend across an area of 235 thousand square kilometers (14). Caribbean societies share a common history of colonialism, slavery, and plantation industry which has given shape to a strong Caribbean identity (15). The same historical and social context has influenced the diversity of sociocultural and political landscapes of the region. Caribbean societies have a rich mixture of cultural influences, including that of Indigenous Amerindians along with European, African, Asian (East Indian and Chinese), and Middle Eastern influences. This diversity is visible in the racial and ethnic makeup of the Caribbean people as well as in the vast array of political systems, languages, religions, music styles, and rituals and traditions (16,17). Along with the uniqueness of the Caribbean, other social cultural factors influence health outcomes.

Impoverished socioeconomic conditions contribute to poor health outcomes and increase the risk for deepening inequalities (18). In particular, poverty and lack of formal education, as well as population and household patterns, augment the inequalities associated to poor health outcomes (18–20). With some variation, the Caribbean experiences elevated levels of poverty and economic hardship. A comparison of the Gross National Income (GNI) of Caribbean countries based on purchasing power parity (PPP) per capita reveals that the region is among the lowest in the world, second only to Sub-Saharan Africa (21). In 2008, Caribbean people had an estimated $9,916 PPP per capita (21) roughly $2,000 below the PPP per capita in Central America, a comparable region with emergent economies, and roughly $200 below the world’s average PPP per capita. The United Sates’ PPP per capita was almost five times higher than that of the Caribbean ($45,890) (21).

Reports reveal high illiteracy rates in some parts of the Caribbean and increasing school drop-out rates, mainly among boys in secondary education (22). According to regional data, 67% percent of the head of households in CARICOM countries have an education level equal-to-or-below elementary school (23) while roughly 23% of them have a secondary level education, and just 10% have a post-secondary level education (23). Additionally, a significant emigration of highly skilled people from the region (“brain drain”) heightens the problem, aggravating education and poverty levels (23–25). Poor level of education can have serious social effects, including crime, youth unemployment, and teenage pregnancy, further contributing to the unfavorable socioeconomic conditions in the region (22).

Public health indicators reflect the impoverished socioeconomic condition of the region. Undernourishment remains a region-wide problem. Nearly 18% of the people in the Caribbean are undernourished (26), the highest rate in the Western hemisphere and second only to Sub-Saharan Africa (27%) (26). Other health indicators are just as striking, specifically among children and women. Eleven percent of children under the age of five are classified as underweight, a rate higher than that found in North (1%), South (4%), and Central America (6%) (27). Research has also found increasing numbers of female-headed households in the Caribbean. Forty-one percent of households are headed by women in the Caribbean (23), a high percentage in comparison to the US, for example, where 19% of households are headed by women (28). Although research has found disputing evidence, female-headed households are widely perceived to be more economically and socially vulnerable (29).

Population trends are suggestive of the inadequate social environment affecting health outcomes in the region (30,31,23). Despite the low numbers in total population, most Caribbean islands have large populations living in urban areas; two thirds of the people live in cities (14). For example, in Latin Caribbean (Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Puerto Rico), 75% of the population is concentrated in urban areas, a trend that is paralleled in the US (79%) and other developed nations (14). Given the urbanized population trend, combined with small territories, many of the Caribbean island nations experience high levels of population density. On average, the Caribbean has a population density of 179 people per square kilometer (the world’s population density is estimated at 51 people per sq. km) (14). Bermuda (UK) has the highest population density in the region, 1,249/sq. km. (14). Along with Saint Maarten (Netherlands and France), these islands rank among the nations with the highest population density in the world (32). The Bahamas has the lowest population density in the Caribbean (28/sq. km) (32). Overcrowded urban cities exacerbate public health problems because of poor living conditions, inadequate sanitation infrastructure, and higher probability of exposure to communicable diseases (2,33).

METHODS

Community leaders, academics, public health professionals, medical personnel, and government officials attended the two-day summit. Leading health disparity researchers, along with health and government representatives from eight Caribbean nations, six US states, and Washington D.C., participated in the two-day meeting. The agenda included (a) plenary sessions covering the summit’s primary topics: Barriers/challenges to Best Practices and Best Practice Models, (b) keynote speeches by renowned public health professionals, researchers, and government officials, and (c) two workgroup sessions to generate recommendations and follow-up actions.

The workgroup sessions aimed to: (a) identify barriers and challenges to integrating health promotion, primary care, and effective interventions based on the social determinants of health and (b) make recommendations on how to improve health outcomes with proven successful practices. The recommendations were transcribed and analyzed; the most salient and recurrent themes from each session are reported in the Results Section.

RESULTS

This section summarizes recommendations from the two workgroups at the summit. The discussions ranged widely, reflecting the diverse background, expertise, experience, and creativity of the attending stakeholders. While the participants found consensus in terms of primary barriers and challenges, the recommendations to improve health practices and interventions to impact health outcomes varied.

Barriers and challenges to best practices in the Caribbean

Successful implementation of best practices to improve health outcomes in the Caribbean requires a multifaceted approach. Barriers and challenges to successful practices are related to (a) limited research resources, (b) policy and governance, (c) communication and community engagement, and (d) lack of skilled health care personnel.

1. Limited research resources

Research is a tool used to explore areas of concern for both communicable and chronic disease within a population. Research findings allow for the proper appropriation of funds and development of relevant public health policy. Compared to regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia, health indicators for the Caribbean may suggest less need for aid. For example, the classification of developed nation may preclude Barbados from potential funding with regard to health research and initiatives. Within the region, limited resources are typically prioritized to address acute care over preventive medicine. Due to a fragmented individualized approach by multiple Caribbean nations in applying for a small pool of funding opportunities, the chances of securing money to implement research efforts are decreased.

Limited epidemiological surveillance and data prevent accurate assessment of health issues as well as the development of appropriate and effective interventions. The Caribbean Epidemiology Center (CAREC) and PAHO, along with other agencies are regional organizations that conduct epidemiological and health research (34). However, because of a range of issues, such as lack of infrastructure for surveillance, accurate data collection has not been actualized. Epidemiology is the cornerstone for research as it allows for primary data collection and direct observation of health trends in a population, and for secondary data analysis to study a broad range of multi-tiered health issues, which ultimately guide policy development.

2. Policy and governance

In terms of a unified approach, several Caribbean organizations (i.e. CARICOM, ACS) promote regional economic integration and development (35). However, not all Caribbean nations are equal members in these organizations or participate in the programs available to members. In terms of health, regional organizations, including PAHO, have limited power and jurisdiction as every nation has ultimate authority over its own health policy and governance.

Governments are limited in their capacity and scope of work due to finite resources and therefore rely on partnerships with private and non-governmental bodies to execute health and research initiatives. At a local level, low levels of funding prevent new health initiatives, even when policymakers are in agreement, thus requiring external assistance. However, governments, local health practitioners, and researchers remain wary of foreign researchers and practitioners entering countries under the auspices of other governments. Furthermore, although the motives of foreign health professionals and researchers may have a potentially favorable outcome for Caribbean societies, there are ethical and legal considerations. For example, foreign practitioners, such as volunteer medical teams, may not abide by local regulations. These policies, intended to protect the safety of citizens, can prevent foreign practitioners from providing care until they meet the established standards of care.

3. Communication and community engagement

There is a general perception among community members that government representatives, health workers, and researchers have an apathetic approach toward the community’s health needs. Summit attendees suggested that in order to ameliorate this situation, and improve the working relationships between government and private sectors (domestic and international), several factors need to be considered. For example, there is a need for more transparency between the parties. Agencies, especially government institutions and research entities, need to foster trust and facilitate an environment of collaboration conducive to establishing goals and agendas to improve the health of the community and population at large.

4. Lack of skilled health personnel

There is a shortage of health professionals as the region suffers from a substantial brain drain, with skilled laborers migrating to regions/countries with better economic opportunities, mainly North America and Europe (25,36,37). One consequence of the region’s brain drain is a shortage of qualified health personnel not only for research and preventive medicine, but also for acute and hospital care. Complicating matters, personnel who remain in the region or have been repatriated have a low level of volunteerism in public health initiatives; strenuous work schedules are not uncommon for Caribbean health personnel (38). These factors negatively impact the quality of health care for those in the lower socio-economic levels of society. Compounding the problem, local health professionals are not always receptive to foreign health professionals migrating to the region. Although these professionals help alleviate the shortage of medical professionals, they are also perceived as professional and economic competition.

Best practices for integrating health promotion, primary care, and sociocultural determinants of health in the Caribbean

Important recommendations were put forth at the Best Practices workgroup session. The recommendations for improving health outcomes, grouped into five major themes, highlight the need and importance of involving the community as an equitable partner to improve the region’s health.

1. Examining community-specific needs taking culture into consideration

First, because areas of the Caribbean have limited access to health care, health care delivery must be evaluated and expanded. Practitioners need to service patients at community-level sites, as people may not have the means or transportation to travel. As a successful model to follow already in place in the Caribbean, community health centers have established satellite clinics and home-based programs, in some cases as a result of partnerships with foreign organizations (39). Second, culturally relevant interventions are critical to the success of health initiatives. Therefore, community motivations, values and beliefs, social norms, and political views need to be considered and made a priority in the development of health strategies and interventions. Considering the cultural values of the community in the delivery of health care is a crucial step in enhancing the community’s level of trust in practitioners and providers. Third, the success of best practice interventions hinges on building a trusting environment with the community. To build trust, practitioners and researchers must consider and propose deliverables that are feasible and obtainable. Failure to deliver promised outcomes could potentially characterize practitioners as unreliable and self-serving, continuing the negative perception of providers and eroding key relationships needed to improve health delivery.

2. Recognizing the self-reliance and autonomy of community

Participants at the summit were passionate about the need to recognize the difference between strengthening and empowering community. This point was well articulated by a community leader from Florida who indicated that “no one can empower us (the community), we empower ourselves.” Acknowledging the inherent skills of a community and its members and relying on their assets will assist in strengthening the community’s empowerment. In fact, participants recounted that the most successful programs focus and build on existing community resources and assets, and include community stakeholders as key collaborators. Along these lines, participants also called for opportunities where community members can participate equally in the processes of developing, implementing, leading, and monitoring health programs.

3. Engaging the political environment

A deep understanding of the political environment is a critical factor in the process of creating best practice interventions. Summit attendees noted the importance of acknowledging the influence of elected officials on health policies. Community members have a responsibility to evaluate political candidates’ positions on health issues and learn how community health can be affected by electing certain candidates into office. Self-reliance involves the awareness that political decisions play an important role in determining health policies and the allocation of funds. Similarly, public health and community leaders are responsible for informing politicians about pressing health problems and the consequences of neglecting these issues, thus the importance of involving the community in setting health policy agendas. Finally, practitioners need to manage and learn where the community’s apathy is generated and respond by bringing awareness and encouraging mobilization.

4. Having a comprehensive approach to health care

According to participants, community intervention in the Caribbean must involve a holistic approach that includes different aspects of social life, such as: early intervention school programs, law enforcement, and faith-based organizations. The approach requires being active in identifying and engaging gatekeepers to learn about needs and interests, and acknowledging their role in the success of the interventions or as non-traditional providers. Best practices in the Caribbean will challenge researchers and practitioners to change the paradigm of who needs to deliver health information and, perhaps, how the information is delivered to adopt appropriate and specific models for the region. For example, successful interventions in the past have engaged community members, including hair stylists, barbers, store owners, and natural healers, to become health educators (40).

5. Long-term sustainability

Lastly, the participants at the summit expressed the necessity to plan creatively for sustainability. In view of limited resources, sustainability is integral to public health in the Caribbean. Sustainable approaches require thinking in alternative ways to solve or alleviate problems. Some successful interventions have provided training opportunities for community members, such as initially becoming a health promoter and then continuing their training to become a licensed or registered practitioner. Practitioners and researchers can collaborate to develop systems that provide opportunities for basic training, skill-building, and professional careers. Lastly, effective sustainability also includes mentoring systems for community members to seek funding, conduct research, and assess the impact of the interventions.

CONCLUSION

The Caribbean is the region most impacted by chronic non-communicable disease epidemics in the Americas (3). Additionally, HIV/AIDS continue to devastate the region (41). Furthermore, as leading causes of death in the region, these epidemics explain much of the premature loss of life and increased burden of disease in the Caribbean. As expected, sociocultural determinants are major factors driving these epidemics, affecting health outcomes among Caribbean people. The Triangulating on Health Equity Summit aimed to build on previous efforts to reaffirm the urgency of addressing health problems in the Caribbean with concrete recommendations. The conference’s theme, improving the region’s health outcomes by adopting effective practices that link health promotion and primary care within the context of social and cultural determinants, called for considering comprehensive models that recognize the role of sociocultural determinants as a driving force behind the health outcomes in the region.

Improving health in the Caribbean is a daunting and complex task given its diversity and the range of factors involved. The recommendations put forth by the participants of this summit reflect not only the urgency to address epidemics that continue to negatively impact the region’s health, but also the reality that these conditions are preventable. As noted in the recommendations, efforts to improve health outcomes in the Caribbean will require active participation from the scientific community, specifically in regard to adopting better systems of data collection, analysis, and dissemination. Well-informed decisions can set health priorities and specific agendas in a focused, objective matter. Thus, addressing the health needs of the people in the region will involve developing strategies targeting the root causes of negative health trends with policies and practices that promote and support access to care as well as healthy diets, physical activity, prevention of harmful alcohol use, and reduction of sexual risk behaviors, along with other issues. In essence, the recommendations seek to develop effective mechanisms that emphasize translating research into practice to improve health outcomes.

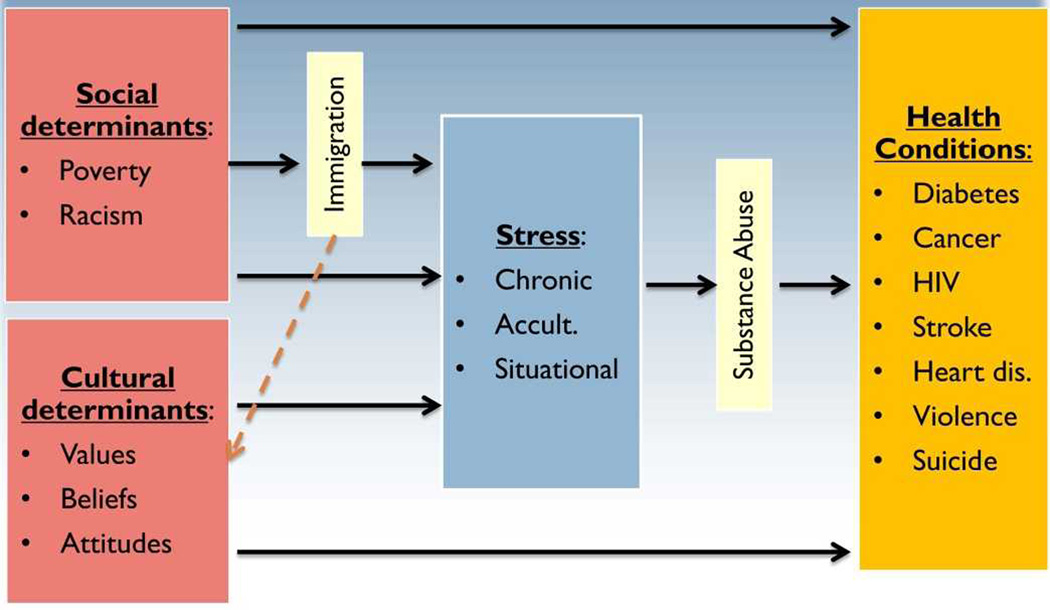

Recommendations from the summit support findings reported by the Caribbean Commission on Health Development in that these complex health issues need to be addressed in a collaborative and holistic manner (42). It is important that this process include the development of conceptual models that recognize the multiplicity of sociocultural factors, reflect their interaction and relationship to health outcomes, and identify specific conditions impacting the quality of life and health of the population. During the summit, Dr. Mario De La Rosa, a leading health disparity researcher, presented a conceptual working model that identifies interrelated factors influencing health conditions (Figure 2). In an effort to go beyond establishing a relationship between sociocultural determinants and health conditions, Dr. De La Rosa challenged the attendees to examine additional factors specific to the Caribbean (e.g. immigration, stress, substance abuse) as key determinants influencing the region’s health. With that in mind, efforts can benefit from considering: (a) research into the causes of poor health outcomes; (b) environments to translate research into practice efficiently; (c) partnership and collaborations that extend beyond national and regional boundaries; and (d) policies reflecting health priorities. In sum, the objective moving forward is to build on these recommendations to develop action-oriented agendas that integrate research, practice, and policy with the goal of improving the health of the Caribbean people.

Figure 2. Caribbean comprehensive health status conceptual model (44).

The recommendations and suggestions presented in this article represent the thoughtful assessments of scientists, health practitioners, government officials, and community members that have dedicated years to the health care field in the Caribbean. This article synthesizes and reflects the wealth of information discussed at this forward-looking summit. It is the desire of the authors that this article encourages further discussion and contributes to the conversation that will improve practices and interventions to advance health in the Caribbean and beyond.

Contributor Information

Francisco Sastre, Email: Francisco.Sastre@fiu.edu, Center for Substance Use and HIV/AIDS Research on Latinos in the United States (C-SALUD), Florida International University, 11200 SW 8th Street, PCA 355A, Miami, Florida 33199, USA.

Patria Rojas, Email: proja003@fiu.edu, Center for Substance Use and HIV/AIDS Research on Latinos in the United States (C-SALUD), Florida International University, Miami, Florida, USA.

Elena Cyrus, Email: ecyru002@fiu.edu, Center for Substance Use and HIV/AIDS Research on Latinos in the United States (C-SALUD), Robert Stempel College of Public Health and Social Work, Florida International University, Miami, Florida, USA.

Mario De La Rosa, Email: delarosa@fiu.edu, Center for Substance Use and HIV/AIDS Research on Latinos in the United States (C-SALUD), Florida International University, Miami, Florida, USA.

Aysha H. Khoury, Email: ahkhourymd@gmail.com, Department of Community Health and Preventive Medicine, Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

REFERENCES

- 1.PAHO. Strategic Plan of Action for the Prevention and Control of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) for Countries if the Caribbean Community. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mutatkar RK. Public Health Problems of Urbanization. Soc Sci Med. 1995;Vol.41(7):997–981. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00398-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shirley Augustine. Facing the Challenge of the CNCD Epidemic: The Global Situation & a Caribbean Perspective. Presented at Capacity Building Workshop - conducted by the Dominica National Commission on Chronic non Communicable Disease. 2010 Jan; Available from: http://www.healthycaribbean.org/presentations/dominica-cncd-jan2010/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 4.CARICOM. [Accessed August 2011]; Available from: http://caricom.org. [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Caribbean Epidemiology Centre PAHO/WHO Epidemiology Division, Statistics Unit. Leading Causes of Death and Mortality rates in Caribbean Epidemiology Centre member Countries. 2005

- 6.UNAIDS/WHO. AIDS Epidemic Update. 2005 Dec; Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/dataimport/publications/irc-pub06/epi_update2005_en.pdf.

- 7.WHO. Preventing chronic diseases: a vital investment. WHO global report. 2005

- 8.Knews Obesity, hypertension leading causes of death in Caribbean – PAHO. [Accessed May 2013];2011 Decemmber; Available from: http://www.kaieteurnewsonline.com/2011/12/18/obesity-hypertension-leading-causes-of-death-in-caribbean-paho. [Google Scholar]

- 9.CARICOM. Report of the Caribbean Commission on Health and Development. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Best T. Barbados shines globally, joins ranks of the ‘developed’ nations. [Accessed August 25, 2011];Daily News. 2010 Nov 8; Available from: http://www.nationnews.com/articles/view/barbados-shines. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montgomery M, Elimelech M. Water and sanitation in developing countries: Including health in the equation. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:17. doi: 10.1021/es072435t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casas JA, Dachs JN, Bambas A. Health Disparities in Latin America and the Caribbean: The role of social and economic determinants. Washington DC: PAHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gowricharn Ruben. Caribbean Transnationalism: Migration, Pluralization, and Social Cohesion. Lanham: Lexington Books; 2006. p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Population Reference Bureau. PRB 2011 World Population Data Sheet. [Accessed May 2013]; Available from: http://www.prb.org/DataFinder/Topic.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serbin Andres. Towards an Association of Caribbean States: Raising Some Awkward Questions. J Inter Am Stud World Aff. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 16.The World Facebook. The Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2098.html.

- 17.Carrington L. The Status of Creole in the Caribbean. Caribb Q. 1999;Vol. 45(No. 2/3):41–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40654079. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans T, Whitehead M, Diderichsen F, Bhuiya A, Wirth M, editors. Challenging inequities in health: from ethics to action. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski JM, et al. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality. JAMA. 1998;279:1703–1708. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pappas G, Queen S, Hadden W, Fisher G. The increasing disparity in mortality between socioeconomic groups in the United States, 1960 and 1986. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:103–109. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307083290207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Population Reference Bureau. 2008 Population Reference Bureau Data Sheet. [Accessed August 25, 2011]; Available from: http://www.prb.org/pdf08/08WPDS_Eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.ECLAC. Caribbean Regional Report for the Five-Year review of the Mauritius Strategy for the Further implementation of the Barbados Programme of Action for the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States (MSI+5) 2010 May 4; [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ebanks GE. Children and youth of the CARICOM Countries, 2000–2001. [Accessed: August 11, 2011];2009 Available from: http://www.caricomstats.org. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanner A. Emigration, brain drain and development: The case of Sub-Saharan Africa. Helsinki Finland: East-West Books; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pang T, Lansang M, Haines A. Brain drain and health professionals. BMJ. 2002;324:499–500. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7336.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.FAO, WFP and IFAD. The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2012. Economic growth is necessary but not sufficient to accelerate reduction of hunger and malnutrition. Rome: FAO; 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Population Reference Bureau. Underweight Children under Age 5, 2007. [Accessed May 2013]; Available from: http://www.prb.org. [Google Scholar]

- 28.U.S. Census Bureau. Households and Families: 2010. 2010 Census Briefs. 2010 Available from: http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-14.pdf.

- 29.Arias E, Palloni A. Prevalence and Patterns of Female-Headed Households in Latin America. 1996 CDE Working Paper No. 96-14. Available from: www.ssc.wisc.edu/cde. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hardoy JE, Cairncross S, Satterthwaite D, editors. The Poor Die Young: Housing and Health in Third World Cities Earthscan. London: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown, Dennis AV. United Nations Publication. Serie Població y desarrollo 25. Santiago, Chile: CEPAL. Population Division of ECLAC – Latin American and Caribbean Demographic Centre (CELADE); 2002. Apr, Sociodemographic vulnerability in the Caribbean: an examination of the social and demographic impediments to equitable development with participatory citizenship in the Caribbean at the dawn of the twenty-first century. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heal The World Foundation. Population density by country. Available from: http://www.NationMaster.com/red/graph/geo_pop_den-geography-population-density&b_printable=1. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stephens C. Healthy cities or unhealthy islands? The health and social implications of urban inequality. Environ Urban. 1996;8:9. Available from: http://eau.sagepub.com/content/8/2/9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.PAHO. [Accessed August 2011];Caribbean epidemic center. Available from: http://new.paho.org/carec/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=24&Itemid=122. [Google Scholar]

- 35.CARICOM. Available from: http://www.caricom.org/jsp/community/history.jsp?menu=community. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nurse K, Jones J. Brain Drain and Caribbean-EU Labour Mobility. Shridath Ramphal Centre for international Trade Law, Policy and Services, UWI, Cave Hill Barbados. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ferguson J. Migration in the Caribbean: Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Beyond. Minority Rights Group International; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yan J. Health Services Delivery: Reframing Policies for Global Nursing Migration in North America--A Caribbean Perspective. Policy Polit Nurs Pract. 2006;7:71S. doi: 10.1177/1527154406294629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caribbean Hospital of Philadelphia Global Health. [Accessed August 2011];Caribbean Program: Niños Primeros en Salud. Available from: http://www.chop.edu/about/chop-in-the-community/global-health/centro-de-salud-divina-providencia-in-the-dominican-republic.html. [Google Scholar]

- 40.UNAIDS. Condom Social marketing: Selected Case studies. [Accessed August 2011];2000 Available from: http://data.unaids.org/publications/IRC-pub02/jc1195-condsocmark_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 41.The Status of HIV in the Caribbean (UNAIDS 2010) UNAIDS Caribbean Regional Support Team. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/countryreport/2010/2010_hivincaribbean_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caribbean Commission on Health and Development. Report of the Caribbean Commission on Health and Development. [Accessed August 2011];2006 Available from: http://www.who.int/macrohealth/action/PAHO_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 43.WHO. The top 10 causes of death - 2008. [Accessed August 2011];Fact sheet No310. 2011 Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 44.De La Rosa M. Caribbean comprehensive health status conceptual model presented during Keynote speech. Triangulating on Health Equity: Best Practices in Integrating Health Promotion, Primary Care, and Social Determinants to Improve Community Health Outcomes; July 22, 2011; San Juan, Puerto Rico. [Google Scholar]