Abstract

Inflammation plays an integral part in tumor initiation. Specifically, patients with colitis, pancreatitis, or hepatitis have an increased susceptibility to cancer. The activation, mutation, and overexpression of oncogenes have been well documented in cell proliferation and transformation. Recently, oncogenes were found to also regulate the inflammatory milieu in tumors. Similarly, the inflammatory milieu can promote oncogene activation. In this review, we summarize advances of the symbiotic relationship oncogene activation and inflammation in gastrointestinal tumors such as colorectal, hepatic, and pancreatic tumors. NF-κB and STAT3 are the two most common pathways that are deregulated via these oncogenes. Understanding these interactions may yield effective therapeutic strategies for tumor prevention and treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Oncogenes are key drivers of tumorigenesis with inflammation promoting many aspects of tumor development such as initiation, progression, and metastasis. Although many authors have discussed the importance of inflammation during these processes, the effect of oncogene activation on inflammation is only recently starting to be unraveled (1–3). In this review, we discuss the latest advances in determining how oncogenes or microRNAs (miRNAs) maintain and fuel inflammation, which promotes oncogene-mediated tumor growth, in an organ-specific context, in gastrointestinal cancers such as colorectal, hepatic, and pancreatic cancers. Oncogene-induced inflammation, or vice versa, is also a crucial feature in other organs.

Colorectal Cancer

The colon is one of the best organs in which to study the crosstalk between oncogenes and inflammation because inflammation plays a key role in colorectal cancer (CRC) development. Patients with persistent colon inflammation or ulcerative colitis are highly predisposed to developing CRC (4, 5). One reason for this propensity is that epithelial cells in this organ are in close contact with the microbiota (6). Below we delineate how inflammatory signals and oncogene activation form a symbiotic relationship for gastrointestinal tumors to grow.

Inactivation of p53 or APC

High levels of p53 (suggestive of mutated p53) are seen in the inflamed colonic tissue of colitis patients, even before neoplastic lesions have formed (7). Only recently was a mechanistic link identified between mutant p53 and sustained inflammation. Both in vitro and in vivo, Cooks et al (7) found that different tumor cell lines that harbored mutant p53 were prone to sustained nuclear factor- (NF-κB) activation (inflammatory pathway) in the presence of low levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF). In addition, these authors elegantly demonstrated that in mice, one copy of mutant p53 promoted colitis and inflammatory bowel disease-mediated carcinogenesis by sustaining NF-κB activation. Mutant p53 can bind and sequester wildtype p53 from binding DNA and inducing downstream signaling. The ability of mutant p53 to sustain NF-κB signaling could be attributed to the loss of wild-type p53 by the mutant p53, but these events were not recapitulated by loss of p53, thereby suggesting a causal link between the mutant p53 oncogene and NF-κB activation in these tumors (Figure 1).

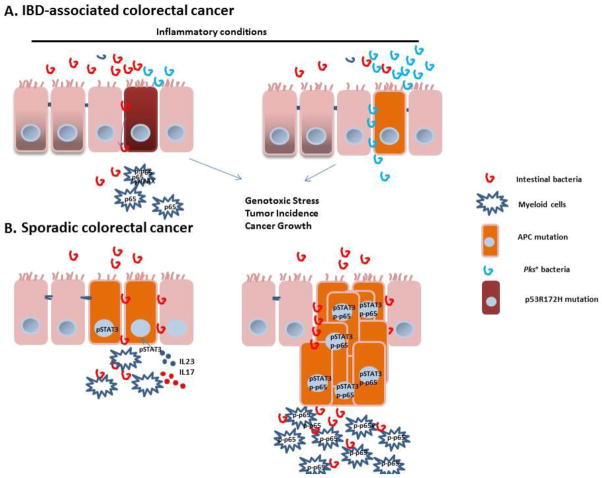

Figure 1. Mechanisms of oncogene-induced inflammation in the colon under inflammatory and non-inflammatory conditions.

A) The disruption of the microflora barrier is an early event in CRC tumorigenesis. The disrupted tight junction in the colon epithelial barrier creates a leak of microbiota or enterotoxins; these toxins promote the inflammatory signature in these tumors. Mutant p53 promotes colitis and inflammatory bowel disease-mediated carcinogenesis by sustaining NF-κB activation. S1P is another molecule that induces NF-κB activation in the myeloid cell compartment, which induces release of IL6 to further sustains adenoma growth/survival. Additionally, the microbiota can promote tumor formation directly by causing genotoxic effects in epithelial cells via pks-positive bacteria.

(B) Oncogene activation is the driving force in microbiota barrier disruption during CRC. Inactivation of APC or AOM/loss of p53 loss results in the loss of mucin production and the aberrant expression of junction proteins. In addition, loss of p53 in enterocytes downregulates proteins that are involved in tight junctions and mucin, resulting in the release of bacteria into the bloodstream. The accumulation of these bacterial products in lesions activates inflammatory cells to produce IL-23 and IL-17; in return, this production promotes growth in transformed cells by upregulating STAT3 in tumor cells. Loss of p53 induces NF-κB activation in both enterocytes and myeloid cells.

Oncogenes promote an inflammatory signature, not only during disease initiation but also metastasis. The loss of p53 in enterocytes that were previously treated with carcinogens induces invasive tumors (8). Loss of p53 in enterocytes induces NF-κB activation in both enterocytes and myeloid cells. Activation of this pathway has a different function in these two cell types: activation of NF-κB in enterocytes induces myeloid cell recruitment and EMT induction; meanwhile, NF-κB activation in myeloid cells induces invasive cancer cell proliferation and spread (8). The downstream function of NF-κB activation in myeloid cells may occur through STAT3 activation, as an absence of NF-κB in myeloid cells reduces STAT3 activation in tumors. The exact communication between these two transcription factors is not clear.

Interestingly, inactivation of APC or p53 at different stages of the disease in a different microenvironment recapitulates different aspects of the disease. More specifically, inactivation of APC, which is considered an early event in spontaneous CRC, causes adenoma polyps (9). Mutated p53 is seen later in spontaneous CRC patients and is correlated with a more aggressive phenotype (9, 10). Mice with mutant p53 that are subjected to dextran sodium sulfate-mediated colitis have flat dysplastic lesions that progress to invasive carcinomas, mimicking the course of the disease seen in colitis-associated CRC (7). It is also relevant that these p53 mutations can be seen in colitis patients even though dysplastic lesions are absent, suggesting that p53 mutations are an early step in inflammatory bowel disease-associated cancers (7, 10).

The role of oncogene mutations in immune or stroma cells in solid tumors is rarely studied. Many examples in the medical literature suggest that mutated tumor suppressor genes such as p53 are present in both epidermal tissue and the tumor microenvironment (11). For example, mutant p53 promotes inflammation via sustained activation of TNF-mediated NF-κB (7). These studies were performed when mutant p53 was present in both epidermal and non-epidermal tissue. p53 accumulation is seen in colon cells, but high levels of p53 accumulation (suggestive of mutant p53) are also seen in the connective stroma and immune cells of dextran sodium sulfate-treated mice (7). Similarly, p53 accumulation in non-epithelial cells was observed in patients with colitis. Other researchers have found that NF-κB activation in immune cells induces pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-23 and IL-17, which are crucial to the maintenance of the pro-inflammatory feedback loop (12). Therefore, one could conclude that sustained oncogene activation in epidermal or stromal cells drives a vicious cycle that sustains inflammation and cancer-related inflammation.

The Sphingosine 1-Phosphate (S1P) pathway may be the missing link between inactivation of both p53 and APC and chronic inflammation in colorectal cancers (13). S1P, a pleiotropic bioactive sphingolipid metabolite, is catalyzed by Sphk1 enzyme which is upregulated in patients with colitis and colon cancer; lack of this enzyme reduced crypt formation and tumor development in a CRC model (14, 15). S1P signals through its receptor, Sphingosine-1 Phosphate Receptor 1 (S1PR1), and induces NF-κB signaling in hematopoietic cells (13). Upregulation of NF-κB in these hematopoietic cells results in upregulation of IL6 and STAT3, which forms a feedback loop and upregulates S1PR1, thereby forming a malicious feedback loop between S1P and NF-κB /IL6/STAT3 in driving colitis and CRC (13, 16). Additionally, Sphk1 proteolysis is a direct target of p53 (17). Sphk1 deletion in p53 null mice prevented lymphoma incidence and increased median survival. Therefore, absence of p53 may modulate NF-κB via fueling the S1P and NF-κB /IL6/STAT3 feedback loop. Independently, Sphk1 is expressed and required for small intestinal tumor cell proliferation in APCMin/+ mice (18), thereby, suggesting that SIP pathway is important in linking inactivation of tumor suppressors and chronic inflammation in colorectal cancers.

While oncogene activation can indeed affect inflammatory pathways, how inflammation affects oncogenic/tumor suppressor activities not so well understood. Inflammatory signals can affects mutated stem cells. Indeed, it is believed that in the colon, cancer arises from initial events occurring mainly in the stem cells, whereas oncogenic events in these cells can give an advantage for the cells to proliferate and grow. p53 mutation in the stem cell of the crypts gives an additional advantage for these stem cells to grow and replace wildtype cells during stochastic stem cell compensation model only under inflammatory conditions but not otherwise (19). One possibility why mutant p53 confers advantage is the inflammation-associated release of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (20) stabilize mutant p53 (21), which in turn promotes proliferation of these cells.

On the other hand, K-RASG12D mutation or APC loss in the stem cells can give an advantage to these stem cells, to proliferate more rapidly than the wildtype ones in absence of inflammation (19). Meanwhile, it would be interesting to know whether inflammatory conditions would give an additional advantage to these stem cell harboring K-RASG12D mutation or APC loss.

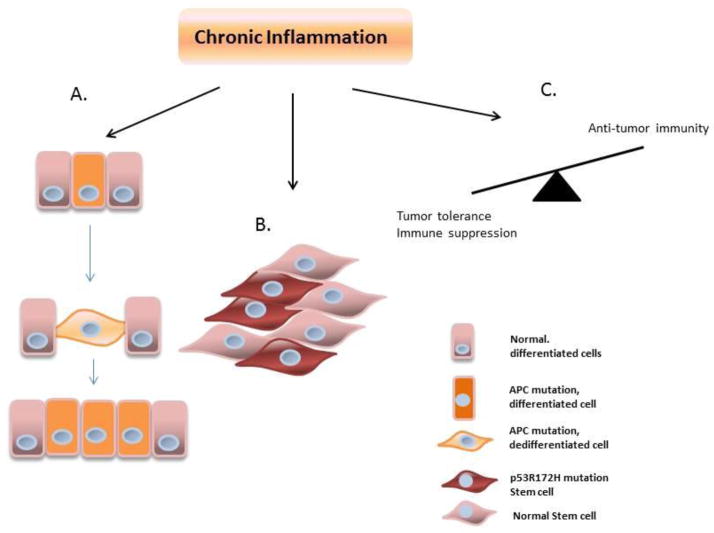

Another important role of inflammatory signals is that aside from providing advantage of mutant p53 stem cells, it can also induce tumor initiation in the colon by de-differentating WNT activated villa (22). Schwitalla et al. and others have recently shown that NF-κB signaling plays a key role in enhancing WNT signaling in a cell autonomous manner (22, 23). RelA recruits CBP to interact with β-catenin which results in increased β-catenin binding activity (22). Furthermore, this group shows in vitro that the ability of K-RASG12D to de-differentiate APC-deficient villus cells is dependent on NF-κB. More evidence of the effect of inflammation during de-differentiation comes from the fact that the absence of APC and NF-κB activation in non-stem epithelial cells is sufficient to induce de-differentiation, promote stem cell signature and tumor formation from these initially non-stem cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The effects of chronic inflammation in the colon during carcinogenesis.

(A) Only under inflammatory conditions, p53 mutation in the stem cell of the crypts in the colon gives an additional advantage for these stem cells to grow and replace wildtype cells during stochastic stem cell compensation model. (B) More evidence of the effect of inflammation comes from the fact that the absence of APC and activation of NF-κB in non-stem cells is sufficient to stimulate dedifferentiation in the enterocytes, induce stem cell signature, and promote tumor formation from these initially non-stem cells. (C) Chronic inflammation promotes tumor tolerance while inhibiting anti-tumor activity.

The role of chronic inflammation during tumorigenesis has been underappreciated. Rather than just inducing immune-suppression, inflammatory stimuli can directly affect oncogene pathways and potentiate oncogene activity of both K-RAS and WNT signaling, and more importantly, can cause de-differentiation in the presence of WNT activation. It is important to note thought, as Schwitalla at al. have suggested, WNT activation alone will not cause de-differentiation (24), but triggering NF-κB activation in addition to a single pathway mutation will indeed produce a stem-like signature in the non-stem cells in the colon, which is different from achieving pluripotency, whereas activation of several transcription factors are needed to induce pluripotency.

Disruption of the Intestinal Barrier

Inflammation plays a crucial role in both inflammation-induced and sporadic colon cancer, but how oncogenes drive inflammation in early sporadic CRC is unknown (absence of colitis). There is emerging evidence that disruption of the microflora barrier is an early event in CRC tumorigenesis. Evidence for this comes from the observation that ApcMin mice bred in germ-free conditions have a two-fold lower incidence of adenoma when compared to animals grown in normal conditions (25). To further prove this point, interleukin-10 (IL-10)−/− mice did not develop colitis-associated cancer when they were rendered germ-free (26). The disrupted tight junction in the colon epithelial barrier creates a leak of microbiota or enterotoxins; these toxins promote the inflammatory signature in these tumors.

Remarkably, oncogene activation is the driving force in microbiota barrier disruption. Inaction of APC or the combination of AOM and p53 loss results in the loss of mucin production and the aberrant expression of junction proteins. In addition, loss of p53 in enterocytes downregulates proteins that are involved in tight junctions and mucin, resulting in the release of bacteria into the bloodstream (12), (8). Furthermore, the accumulation of these bacterial products in lesions activates inflammatory cells to produce IL-23 and IL-17; in return, this production promotes growth in transformed cells. The released bacteria or toxins, such as endotoxin or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), also induce inflammation in tumor cells by activating NF-κB either in the enterocytes or in hematopoietic cells. Studies have demonstrated that short-term depletion of intestinal microflora via a variety of antibiotics downregulates tumor incidence and growth.

Leaky microflora promotes CRC by activating the two major inflammatory pathways, NF-κB and STAT3. The pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-23 and IL-17 play a pivotal role in this process by upregulating STAT3 in tumor cells (12, 27). The oncogene-mediated destruction of tight junctions and upregulation of the inflammatory signature are seen in early adenomas from cancer patients and in tumor-bearing mice. Similarly, mucin expression and the organization of tight junction aberrations are seen in both cases.

Aside from promoting CRC by providing toxins, such as LPS, that activate inflammatory cells in tumors, microbiota can promote tumor formation directly by causing genotoxic effects in epithelial cells (1). Indeed, E. coli with deleted poliketide synthase (pks) has reduced potential in polyp multiplicity and genetic stability in AOM/IL-10−/− colitis-prone mice. Interestingly, it is the inflammation, rather than the carcinogen, that induces 100-fold enrichment of the microbiota pks+ E. coli frequency under inflammatory conditions. In addition, pks+ bacteria promotes multiplicity and cancer growth in concert with an inflammatory environment, but not in the absence of inflammation. These findings suggest that intestinal inflammation has a dual function: enriching for bacteria that have cancer-inducing properties and deregulating the host’s ability to protect itself from these “dysfunctional” microbiota.

Liver

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide (28). Patients with hepatitis B or C (HBV or HCV) are highly susceptible to HCC formation. More than 80% of HCC cases arise in patients with fibrosis or cirrhosis (29). HCC is thought to involve three different steps: massive hepatocyte cell death, followed by progressive liver fibrosis, and finally, HCC enriched for stem cell and oncofetal protein expression (30). These findings suggest that inflammatory responses are precursors to disease initiation and oncogenic transformation.

Involvement of NF-κB Pathway

The degree of activation or inhibition of NF-κB pathway or the presence of inflammation appear to determine whether NF-κB is pro- or anti-tumorigenic. NF-κB is the main pathway to protect liver TNF or LPS induced cell death (31). Complete inactivation of NF-κB by removing NEMO or TAK1 in hepatocytes results in spontaneous massive hepatocyte cell death, process which is followed by compensatory proliferation, fibrosis, inflammation, and HCC formation (32–34)

However, under inflammatory conditions in MDR2−/− mouse model of cholestatic hepatitis, NF-κB activation in hepatocytes has a pro-tumorigenic effect (35). While NF-κB expression in hepatocytes is upregulated during the early phase of inflammation, NF-κB is dispensable during the initial phase of inflammation and dysplasia; yet, this transcription factor is critical in the transitioning stage from dysplasia to malignancy (35). This is mostly due to the ability to induced survival of the transformed cells. Similarly, NF-κB promotes HCC development in another model of inflammation, lymphotoxin-driven HCC (36).

Meanwhile, activation of NF-κB by deletion of the tumor suppressor de-ubiquitinase CYLD in hepatocytes recapitulates the phenotypes seen in HCC patients. Specifically, these mice develop hepatocyte apoptosis, progressive liver fibrosis, and late-onset HCC (37). These effects are due to prolonged activation of JNK and TAK1, which cause cell death. Subsequently, fibrotic lesions are caused by hepatocyte damage, which is triggered by the activation and proliferation of stellate cells via TAK1 activation, spontaneous and progressive Kupffer cell activation, inflammatory cell infiltration, TNF production, and NF-κB activation. Furthermore, mice that lack this gene develop tumors by 1 year of age and express genes enriched for stem cell markers and onco-fetal proteins, genes that are also specifically enriched in patients with HCC (37). Therefore, in summary, complete absence of hyperactivation of NF-κB during the earlier stages of the disease induces HCC development via compensatory mechanisms. Meanwhile, activation of NF-κB in hepatocytes during an ongoing inflammatory disease promotes malignancy via promoting survival of transformed cells.

miRNAs on Liver Inflammation

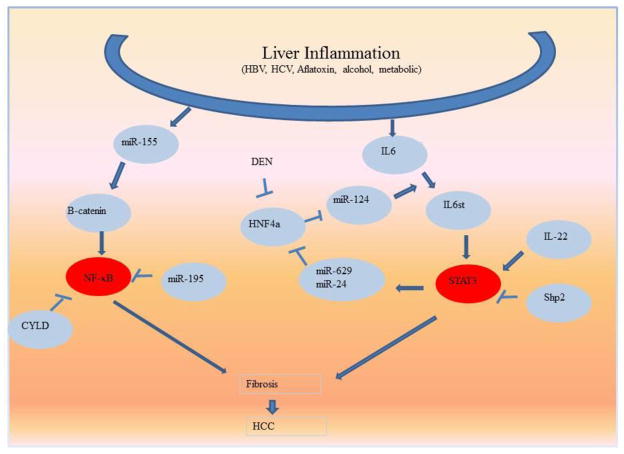

It is unknown why the pro-inflammation milieu that is associated with HBV and HCV causes a high incidence of HCC formation or how it promotes tumor cell transformation. What sustainable genetic changes are induced by these viruses, and how do these genetic alterations sustain inflammation? MiRNAs are central to the association between inflammation and hepatic cancer (38). For example, miR-155 levels were markedly increased in patients infected with HCV. This is of interest because miR-155 is a direct target of HCV; it is upregulated in the inflamed liver prior to HCC development; and it is involved in HCC growth and progression (39). NF-κB activation is involved in regulating miR-155 in the liver, which activates WNT signaling by inducing B-catenin accumulation in the nucleus of hepatocytes. In addition, miR-155 augments cell proliferation and promotes cyclin D1, c-myc, and survivin gene expression. Mechanistically, it directly binds and downregulates APC, which is a tumor suppressor that inactivates WNT/β-catenin (Figure 2). In summary, this study illustrates a mechanistic link between HCV-induced inflammation, WNT activation, and HCC development (39).

Complex circuits provide evidence that hepatocellular oncogenesis is initiated as a result of epigenetic changes; these changes are fueled by the activation of inflammatory molecules that are often upregulated in HBV- or HCV-infected livers. In other words, hepatic inflammation itself can induce epigenetic alterations by regulating the miRNAs that lead to hepatic tumorigenesis. More precisely, transient inhibition of the HNF4a gene resulted in cell transformation, and these transformed cells grew into tumors in vivo (40). The upregulation of miR-24 and miR-629 seems to downregulate this gene at the 3′ region. Interestingly, both of these miRNAs contain a STAT3 binding site in their promoter region. IL-6-induced STAT3 binds to and induces the expression of these two miRNAs, which in turn form a feedback loop and promote their expression by upregulating STAT3 expression. Even more interestingly, another feedback loop exists for how reduced levels of HNF4a promote inflammation. HNF4a upregulates miR-124, which inhibits IL-6 receptor signaling. In other words, the downregulation of HNF4a results in the decrease of miR-124, which increases IL-6 signaling and STAT3 activation. This cascade of events is followed by an increase in miR-24 and miR-629 levels, which sustain the downregulation of HNF4a and hence engage this forward loop. HNF4a is regulated not only by inflammation, but also by the DEN, a potent chemical inducer of HCC (Figure 3). Aside from miR-124, the tumor suppressor miR-126a can reduce IL6, furthermore decreasing STAT3 (41). Furthermore, IL6 in HCC can in turn suppress miR-126a (42).

Figure 3. Epigenetic pathways that sustains cell inflammation and transformation in the liver.

MicroRNAs affect NF-κB and STAT3 activation in the liver, two of the most common pathways that sustain cell inflammation and transformation in the liver.

However, it is not yet clear how DEN downregulates HNF4a expression. In summary, the chemical- or virus-induced inflammatory milieu can reduce HNF4a levels and initiate an epigenetic loop that sustains cell inflammation and transformation (40).

Multiple different stimuli can activate this loop; it is not necessary for HNF4a to be the first step. Aside from DEN-mediated downregulation of HNF4a, sources of perturbation that can initiate or feed into this loop include IL-6/STAT3 activation or IL-22-mediated STAT3 activation (43). Other researchers have found that miR-124 is frequently silenced via methylation in HCC (44). Aside from its function in the liver, the locus of HNF4a was found to be a susceptible gene in colitis (another pro-inflammatory disease that is susceptible to cancer development), suggesting that these loops are not organ specific (45).

Epigenetic changes play a key role in cancer initiation in via regulating IL-6, an important player during HCC development, with IL6 being expressed in at least 40% of HCC samples (46, 47). In the well-characterized DEN-induced HCC model, IL6 is rapidly induced in the Kupffer cells, and is needed for DEN-induced carcinogenesis (48). This transient expression of IL6 in Kupffer cells goes down within 2 weeks, only to reappear within months expressed within the parenchyma cells of FAH, cells which have been suggested to contain progenitor cells that give rise to cancer (47). Indeed, autocrine expression of IL6 in these progenitor cells is needed for the tumorigenic potential of these cells (47). IL6 is kept low in these progenitor cells via LIN28 (47). However, other potential pathways could account for low maintenance of low levels of IL6 in the liver. One such candidate is IL27-p28 subunit, otherwise called IL30, which can bind to gp130 and block IL6 signaling (49). Dibra and colleagues showed that indeed IL30 is heavily expressed by normal hepatocyte cells, and can block inflammatory signaling within the liver milieu (50). It yet remains to be uncovered if and how this cytokine can attenuate the tumorigenic potential of the progenitor cells to obtain autocrine signaling of IL6.

Unlike the pro-tumorigenic miRs, miR-195 was found to be a tumor suppressor RNA in HCC; it acts by downregulating the inflammatory milieu in the liver. Indeed, miR-195 reduces cancer cell proliferation and migration in vitro and reduces tumorigenicity and metastasis in vivo (51). About 60% of HCC patients have two-fold downregulated miR-195, and 35% of patients have lost DNA regions in which this miRNA is expressed. Mechanistically, miR-195 may exert its tumor-suppressing function by directly targeting IKKα and TAK1-binding protein 3, decreasing the expression of multiple NF-κB downstream effectors (51).

The tumor suppressor PTEN can greatly affect inflammation in the liver and HCC formation (52) (53). Indeed, specific deletion of PTEN in hepatocytes leads to accumulation of fatty liver, inflammatory cells, and HCC which is partially due to AKT2, as disruption of both AKT2 and PTEN rescues this phenotype (54). Considering its role in liver steatohepatitis, many microRNAs affect PTEN. Namely, miR-21 is upregulated in HCC and it downregulates PTEN in many cell types in the liver under different conditions (55). Indeed, PTEN is a direct target of miR-21 and inhibition of miR-21 restores the tumor suppressor functions associated with PTEN. Meanwhile, miR-21 can also affect inflammation in the liver via activation of hepatic stellate cells through downregulation of PTEN and activation of Akt. And lastly, miR-21 can reduce PTEN induced by unsaturated fatty acids (56). Aside from miR-21, other microRNAs such as miR-216a/217, miR-29, or miR-106 also affect PTEN expression in the liver (57–59).

Oncogene-Sustained Inflammation

Apart from inflammation-induced miRNA changes that promote hepatogenesis, oncogene-sustained inflammation is also prominent in the liver. β-catenin is another molecule that promotes HCC formation via an inflammatory milieu. Indeed, this transcription factor is commonly mutated in HCC. β-catenin signaling induces an inflammatory program in hepatocytes that involves direct transcriptional control activation of the NF-κB pathway (60). Two downstream factors related to this process are the chemokine-like chemotactic factor leukocyte cell–derived chemotaxin 2 and invariant NKT cells. Indeed, the deletion of leukocyte cell–derived chemotaxin 2 or NKT cells results in the development of highly aggressive and metastatic HCC (60). On the other hand, TNF derived from macrophages can promote β-catenin signaling through inhibition of GSK3β (61)

P53 is another tumor suppressor gene that affects inflammation in the liver, albeit the mechanism how p53 regulates inflammation is complex. Deletion of p53 in the hepatocytes induces liver fibrosis by raising the expression of CTGF synthesis in mouse and human hepatocytes (62). Meanwhile, deletion of the p53 in hepatic stellate cells is associated with an increase in transformation of the adjacent cells (63). Mechanistically, deletion of p53 in stellate cells induces non-cell autonomous microenvironment changes characterized by a tumor-promoting M2 phenotype which enhance the proliferation of the premalignant cells, while p53-expressing stellate cells promote a tumor inhibitory M1 phenotype.

An association between tumor suppressors and downregulation of liver inflammation was seen in mice that lacked the tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 (64). Hepatocyte-specific deletion of Shp2 promotes inflammatory signaling through the Stat3 pathway and hepatic inflammation and necrosis, resulting in regenerative hyperplasia and tumor development in aged mice. Further proof that the absence of this enzyme sensitizes mice to inflammation resulted from treating these mice with LPS, which made them highly sensitive to inflammation compared with their control cohorts. They were also more sensitive to HCC development when challenged with DEN. The enhanced HCC development in mice lacking Shp2 expression in liver was ablated by the additional deletion of STAT3 in the liver cells. Similarly, the inflammatory phenotype associated with the absence of Shp2 in liver cells was ablated when STAT3 was absent (64).

Intestinal Mucosal Permeability

Aside from viruses, hepatic injury is often associated with an increase in intestinal mucosal permeability (65). Translocation of the bacterial products from the gut seems to activate these TLR4 receptors in the liver, as demonstrated by the intestinal bacteria’s ability to affect cirrhosis incidence in mice and by reduced fibrosis in rodents after antibiotic administration (66). Engagement of the TLR4 receptor via LPS in hepatic stellate cells is needed to induce hepatic fibrosis and to promote HCC development under inflammatory conditions (66, 67). One mechanism how intestinal bacteria activate hepatic stellate cells in the liver is via lowering the TGF-β pseudoreceptor Bambi, which sensitizes these cells TGF-β signaling and activation of Kupffer cells (66). Meanwhile, secretion of epiregulin by hepatic stellate cells is partially involved in TLR4-mediated HCC promotion (67).

Therefore, the road from oncogene-induced inflammation to inflammation-induced oncogene expression is complex, with multiple layers of feedback loops in which NF-κB, IL-6, STAT3, and miRNAs (e.g., miR-155, miR-195, and miR-124, miR-21) are most certainly key factors (68).

Pancreas

Just as colitis or hepatitis predisposes patients to CRC or HCC, chronic pancreatitis predisposes patients to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) (69). Pancreatitis increases patients’ chances of developing PDAC by 16-fold (70). However, PDAC patients do not have pancreatitis, which makes the link between these two diseases confusing. K-RAS, the most commonly mutated gene in PDAC, does not cause cancer when it is mutated in adult mice, suggesting that host interactions or additional mutations are needed. The results of one significant study by Guerra et al reconciled these two opposing facts, finding that even short asymptomatic bouts of pancreatitis led to PDAC development in mice, as long as K-RAS was mutated in acinar cells (71).

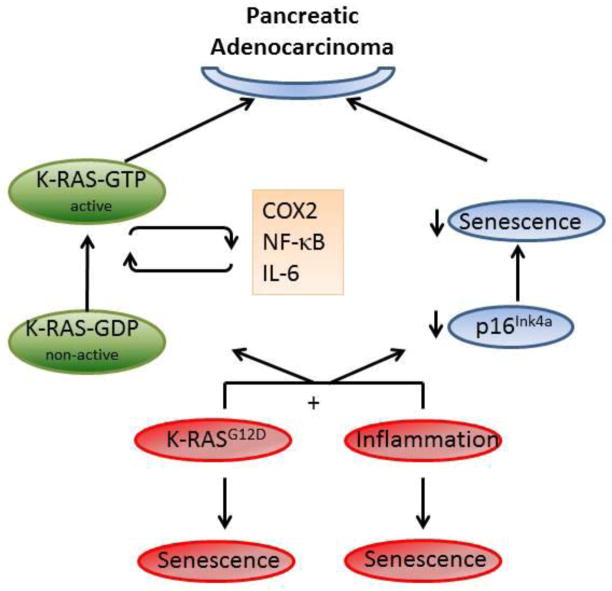

Cellular senescence is a potent tumor-suppressor mechanism. Inflammatory signals or oncogenes alone can induce cellular senescence in the pancreas. However, the co-occurrence of both inflammation and oncogene activation is crucial to bypassing senescence and promoting cell proliferation and pancreatic neoplasms (71, 72). Indeed, Guerra et al (71) found that pancreatitis promotes PDAC by abrogating oncogene-induced senescence in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias. These observations in mice agree with those of the patients, as treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs demonstrated senescence marker upregulation in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasias. Additionally, while inflammation can induce premature senescence of the pancreatic ductal epithelium via upregulation of P16INK4a, K-RAS activation can overcome inflammation-induced cellular senescence in this model (Figure 4). Oncogenic K-RAS upregulates Twist levels, which in turn downregulate inflammation-induced P16INK4a levels (72).

Figure 4. Cooperation of K-RAS and inflammation is needed for pancreatic adenocarcinoma formation.

Inflammatory signals alone, or oncogenes mutation (K-RAS) can induce cellular senescence in the pancreas. Meanwhile, the combination of K-RAS and inflammation in the pancreas can suppress senescence by decreasing p16 levels. Additionally, inflammatory signals can amplify oncogenic K-RASG12D activation to achieve pathogenic potential via COX2, NF-κB activation, or IL6. Amplified K-RAS can sustain inflammation via inducing IL6 and COX2 levels; thereby forming a feedback loop.

Until recently, it was believed that K-RAS mutation induces an active form of the protein, and therefore nothing could be done at this level to inhibit tumor initiation (73). Cleverly, others have shown that oncogenic K-RAS does not necessarily equate to fully activated and pathogenic levels of K-RAS are needed to actually form tumors (73). Indeed, Haojie et al show that oncogenic K-RASG12D requires activation in order to achieve pathogenic potential (74). Additionally, the same group and others showed that inflammatory signals such as COX2, NF-κB activation, or EGF are necessary to amplify RAS levels into pathological levels (75, 76). More specifically, endogenous EGFR signaling is needed for robust induction of activated GTP-bound RAS and downstream signaling ERK, which is critical for neoplasia (76).

Once fully activated, oncogenic K-RAS can induce IL6 and COX2 levels; removal of inducible K-RAS can reverse these levels (77). Furthermore, during the earlier stages after pancreatits, K-RAS prevents repair, induces de-differentiation of the acini, and sustains stroma activation. Meanwhile, during the latter stages after high-grade PanIN have been established, K-RAS function is to maintain proliferation as the removal of K-RAS resulted in shrinkage of tumor size (77). Additionally, COX2 product, prostaglandin E, produced from K-RAS pancreata cells can directly act on stellate cells to induce profibrogenic properties in these cells and sustain an active stroma (78).

Additionally, mutated KRAS can induce other inflammatory molecules to promote a pro-tumorigenic microenvironment, namely GMCSF and IKK2/β (79, 80). Mutated K-RASG12D induces GMCSF, which recruits the myeloid derived suppressor cell. One of the inhibitory roles of these cells is to downregulate CD8+ T cells (79). Activation of IKK2/ β by K-RASG12D on the other hand induces activation of the AP1 to induce IL1a (80). This cytokine in turn activates IKK2/ β to further induce IL1a and p62, thereby a forming a forward feedback loop in sustain K-RASG12D – induced inflammation. One possibility is that GMCSF is also a downstream molecule of K-RAS induced NF-κB activation. Thereby, K-RAS induces an inflammatory milieu, and such inflammation sustains pathogenic K-RAS levels via a positive feedback loop during PDAC.

Concluding remarks

Inflammation plays a decisive role in many aspects of cancer. Since the 19th century, when Rudolf Virchow first observed inflammatory cells in tumors, much progress has been made in understanding the crosstalk between tumors and inflammatory cells and tumor-induced inflammatory genes in the tumors themselves. In this paper, we summarized the most recent findings on oncogenes’ mechanisms to induce and sustain inflammation in gastrointestinal tumors.

We focused on oncogene-induced inflammation because oncogenes are considered initiators and drivers of tumorigenesis (such as K-RAS in the pancreas or activated WNT signaling in CRC), it is typically inflammation caused by HBV, HCV, alcohol consumption, or aflatoxin exposure precedes HCC development (81). In the liver, it seems that chronic inflammation is the driver of HCC formation. It drives the expression of miRNAs, such as miR-155, miR-629, and miR-24, which in turn activate oncogenic pathways, fuel inflammation, cause fibrosis, and result in HCC formation.

Understanding the mechanism of oncogene-induced inflammation, and vice versa, makes cancer more targetable and manageable at the early onset of disease. Targeting these tumor-prone niches before tumors form is a feasible method of improving early detection in patients who are at high risk for developing carcinoma because of inflammatory conditions such as HCV/HBC, colitis, or pancreatitis. Additionally, considering the tight relationship between oncogenes and inflammation and how feedback loops exist to sustain reciprocal expression, targeting simultaneously both pathways seems more sensible.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NCI R01 grant CA120895 and 7P01CA130821.

Footnotes

Competing Interest: The authors declare no competing interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Muhlbauer M, Tomkovich S, Uronis JM, Fan TJ, Campbell BJ, et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science. 2012;338:120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.1224820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haybaeck J, Zeller N, Wolf MJ, Weber A, Wagner U, Kurrer MO, Bremer J, et al. A Lymphotoxin-Driven Pathway to Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer cell. 2009;16:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hernandez-Vargas H, Lambert MP, Le Calvez-Kelm F, Gouysse G, McKay-Chopin S, Tavtigian SV, Scoazec JY, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma displays distinct DNA methylation signatures with potential as clinical predictors. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen GY, Nunez G. Inflammasomes in intestinal inflammation and cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1986–1999. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ullman TA, Itzkowitz SH. Intestinal inflammation and cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1807–1816. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:577–594. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooks T, Pateras IS, Tarcic O, Solomon H, Schetter AJ, Wilder S, Lozano G, et al. Mutant p53 Prolongs NF-kappaB Activation and Promotes Chronic Inflammation and Inflammation-Associated Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:634–646. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwitalla S, Ziegler PK, Horst D, Becker V, Kerle I, Begus-Nahrmann Y, Lechel A, et al. Loss of p53 in enterocytes generates an inflammatory microenvironment enabling invasion and lymph node metastasis of carcinogen-induced colorectal tumors. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:93–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fearon ER. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:479–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brentnall TA, Crispin DA, Rabinovitch PS, Haggitt RC, Rubin CE, Stevens AC, Burmer GC. Mutations in the p53 gene: an early marker of neoplastic progression in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:369–378. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90161-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wernert N, Locherbach C, Wellmann A, Behrens P, Hugel A. Presence of genetic alterations in microdissected stroma of human colon and breast cancers. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:2259–2264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grivennikov SI, Wang K, Mucida D, Stewart CA, Schnabl B, Jauch D, Taniguchi K, et al. Adenoma-linked barrier defects and microbial products drive IL-23/IL-17-mediated tumour growth. Nature. 2012;491:254–258. doi: 10.1038/nature11465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang J, Nagahashi M, Kim EY, Harikumar KB, Yamada A, Huang WC, Hait NC, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate links persistent STAT3 activation, chronic intestinal inflammation, and development of colitis-associated cancer. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snider AJ, Kawamori T, Bradshaw SG, Orr KA, Gilkeson GS, Hannun YA, Obeid LM. A role for sphingosine kinase 1 in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis. FASEB J. 2009;23:143–152. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-118109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawamori T, Kaneshiro T, Okumura M, Maalouf S, Uflacker A, Bielawski J, Hannun YA, et al. Role for sphingosine kinase 1 in colon carcinogenesis. FASEB J. 2009;23:405–414. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-117572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee H, Deng J, Kujawski M, Yang C, Liu Y, Herrmann A, Kortylewski M, et al. STAT3-induced S1PR1 expression is crucial for persistent STAT3 activation in tumors. Nat Med. 2010;16:1421–1428. doi: 10.1038/nm.2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heffernan-Stroud LA, Helke KL, Jenkins RW, De Costa AM, Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Defining a role for sphingosine kinase 1 in p53-dependent tumors. Oncogene. 2012;31:1166–1175. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohno M, Momoi M, Oo ML, Paik JH, Lee YM, Venkataraman K, Ai Y, et al. Intracellular role for sphingosine kinase 1 in intestinal adenoma cell proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7211–7223. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02341-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vermeulen L, Morrissey E, van der Heijden M, Nicholson AM, Sottoriva A, Buczacki S, Kemp R, et al. Defining stem cell dynamics in models of intestinal tumor initiation. Science. 2013;342:995–998. doi: 10.1126/science.1243148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meira LB, Bugni JM, Green SL, Lee CW, Pang B, Borenshtein D, Rickman BH, et al. DNA damage induced by chronic inflammation contributes to colon carcinogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2516–2525. doi: 10.1172/JCI35073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suh YA, Post SM, Elizondo-Fraire AC, Maccio DR, Jackson JG, El-Naggar AK, Van Pelt C, et al. Multiple stress signals activate mutant p53 in vivo. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7168–7175. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwitalla S, Fingerle AA, Cammareri P, Nebelsiek T, Goktuna SI, Ziegler PK, Canli O, et al. Intestinal tumorigenesis initiated by dedifferentiation and acquisition of stem-cell-like properties. Cell. 2013;152:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Umar S, Sarkar S, Wang Y, Singh P. Functional cross-talk between β-catenin and NFκB signaling pathways in colonic crypts of mice in response to progastrin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:22274–22284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dove WF, Clipson L, Gould KA, Luongo C, Marshall DJ, Moser AR, Newton MA, et al. Intestinal neoplasia in the ApcMin mouse: independence from the microbial and natural killer (beige locus) status. Cancer Res. 1997;57:812–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uronis JM, Muhlbauer M, Herfarth HH, Rubinas TC, Jones GS, Jobin C. Modulation of the intestinal microbiota alters colitis-associated colorectal cancer susceptibility. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu S, Rhee KJ, Albesiano E, Rabizadeh S, Wu X, Yen HR, Huso DL, et al. A human colonic commensal promotes colon tumorigenesis via activation of T helper type 17 T cell responses. Nat Med. 2009;15:1016–1022. doi: 10.1038/nm.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seki E, Kondo Y, Iimuro Y, Naka T, Son G, Kishimoto T, Fujimoto J, et al. Demonstration of cooperative contribution of MET- and EGFR-mediated STAT3 phosphorylation to liver regeneration by exogenous suppressor of cytokine signalings. J Hepatol. 2008;48:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fattovich G, Stroffolini T, Zagni I, Donato F. Hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: incidence and risk factors. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S35–50. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marquardt JU, Raggi C, Andersen JB, Seo D, Avital I, Geller D, Lee YH, et al. Human hepatic cancer stem cells are characterized by common stemness traits and diverse oncogenic pathways. Hepatology. 2011;54:1031–1042. doi: 10.1002/hep.24454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doi TS, Marino MW, Takahashi T, Yoshida T, Sakakura T, Old LJ, Obata Y. Absence of tumor necrosis factor rescues RelA-deficient mice from embryonic lethality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2994–2999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luedde T, Beraza N, Kotsikoris V, van Loo G, Nenci A, De Vos R, Roskams T, et al. Deletion of NEMO/IKKgamma in liver parenchymal cells causes steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inokuchi S, Aoyama T, Miura K, Osterreicher CH, Kodama Y, Miyai K, Akira S, et al. Disruption of TAK1 in hepatocytes causes hepatic injury, inflammation, fibrosis, and carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:844–849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909781107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bettermann K, Vucur M, Haybaeck J, Koppe C, Janssen J, Heymann F, Weber A, et al. TAK1 suppresses a NEMO-dependent but NF-kappaB-independent pathway to liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:481–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pikarsky E, Porat RM, Stein I, Abramovitch R, Amit S, Kasem S, Gutkovich-Pyest E, et al. NF-kappaB functions as a tumour promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature. 2004;431:461–466. doi: 10.1038/nature02924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haybaeck J, Zeller N, Wolf MJ, Weber A, Wagner U, Kurrer MO, Bremer J, et al. A lymphotoxin-driven pathway to hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nikolaou K, Tsagaratou A, Eftychi C, Kollias G, Mosialos G, Talianidis I. Inactivation of the deubiquitinase CYLD in hepatocytes causes apoptosis, inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:738–750. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong CM, Kai AK, Tsang FH, Ng IO. Regulation of hepatocarcinogenesis by microRNAs. Front Biosci (Elite Ed) 2013;5:49–60. doi: 10.2741/e595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Wei W, Cheng N, Wang K, Li B, Jiang X, Sun S. Hepatitis C virus-induced up-regulation of microRNA-155 promotes hepatocarcinogenesis by activating Wnt signaling. Hepatology. 2012;56:1631–1640. doi: 10.1002/hep.25849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hatziapostolou M, Polytarchou C, Aggelidou E, Drakaki A, Poultsides George A, Jaeger Savina A, Ogata H, et al. An HNF4α-miRNA Inflammatory Feedback Circuit Regulates Hepatocellular Oncogenesis. Cell. 2011;147:1233–1247. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang X, Liang L, Zhang XF, Jia HL, Qin Y, Zhu XC, Gao XM, et al. MicroRNA-26a suppresses tumor growth and metastasis of human hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting interleukin-6-Stat3 pathway. Hepatology. 2013;58:158–170. doi: 10.1002/hep.26305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang Y, Zhang B, Zhang A, Li X, Liu J, Zhao J, Zhao Y, et al. IL-6 upregulation contributes to the reduction of miR-26a expression in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013;46:32–38. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2012007500155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kong X, Feng D, Wang H, Hong F, Bertola A, Wang F-S, Gao B. Interleukin-22 induces hepatic stellate cell senescence and restricts liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology. 2012;56:1150–1159. doi: 10.1002/hep.25744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Furuta M, Kozaki KI, Tanaka S, Arii S, Imoto I, Inazawa J. miR-124 and miR-203 are epigenetically silenced tumor-suppressive microRNAs in hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:766–776. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Consortium UIG, Barrett JC, Lee JC, Lees CW, Prescott NJ, Anderson CA, Phillips A, et al. Genome-wide association study of ulcerative colitis identifies three new susceptibility loci, including the HNF4A region. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1330–1334. doi: 10.1038/ng.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soresi M, Giannitrapani L, D’Antona F, Florena AM, La Spada E, Terranova A, Cervello M, et al. Interleukin-6 and its soluble receptor in patients with liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2563–2568. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i16.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He G, Dhar D, Nakagawa H, Font-Burgada J, Ogata H, Jiang Y, Shalapour S, et al. Identification of liver cancer progenitors whose malignant progression depends on autocrine IL-6 signaling. Cell. 2013;155:384–396. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, Maeda S, Kim K, Elsharkawy AM, Karin M. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science. 2007;317:121–124. doi: 10.1126/science.1140485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stumhofer JS, Tait ED, Quinn WJ, 3rd, Hosken N, Spudy B, Goenka R, Fielding CA, et al. A role for IL-27p28 as an antagonist of gp130-mediated signaling. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1119–1126. doi: 10.1038/ni.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dibra D, Cutrera J, Xia X, Kallakury B, Mishra L, Li S. Interleukin-30: a novel antiinflammatory cytokine candidate for prevention and treatment of inflammatory cytokine-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2012;55:1204–1214. doi: 10.1002/hep.24814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ding J, Huang S, Wang Y, Tian Q, Zha R, Shi H, Wang Q, et al. Genome-wide screening reveals that miR-195 targets the TNF-alpha/NF-kappaB pathway by down-regulating IkappaB kinase alpha and TAB3 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;58:654–666. doi: 10.1002/hep.26378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Podsypanina K, Ellenson LH, Nemes A, Gu J, Tamura M, Yamada KM, Cordon-Cardo C, et al. Mutation of Pten/Mmac1 in mice causes neoplasia in multiple organ systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1563–1568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Horie Y, Suzuki A, Kataoka E, Sasaki T, Hamada K, Sasaki J, Mizuno K, et al. Hepatocyte-specific Pten deficiency results in steatohepatitis and hepatocellular carcinomas. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1774–1783. doi: 10.1172/JCI20513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He L, Hou X, Kanel G, Zeng N, Galicia V, Wang Y, Yang J, et al. The critical role of AKT2 in hepatic steatosis induced by PTEN loss. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2302–2308. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meng F, Henson R, Wehbe-Janek H, Ghoshal K, Jacob ST, Patel T. MicroRNA-21 regulates expression of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in human hepatocellular cancer. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:647–658. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vinciguerra M, Sgroi A, Veyrat-Durebex C, Rubbia-Brandt L, Buhler LH, Foti M. Unsaturated fatty acids inhibit the expression of tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) via microRNA-21 up-regulation in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2009;49:1176–1184. doi: 10.1002/hep.22737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu K, Ding J, Chen C, Sun W, Ning BF, Wen W, Huang L, et al. Hepatic transforming growth factor beta gives rise to tumor-initiating cells and promotes liver cancer development. Hepatology. 2012;56:2255–2267. doi: 10.1002/hep.26007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poliseno L, Salmena L, Riccardi L, Fornari A, Song MS, Hobbs RM, Sportoletti P, et al. Identification of the miR-106b~25 microRNA cluster as a proto-oncogenic PTEN-targeting intron that cooperates with its host gene MCM7 in transformation. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra29. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tumaneng K, Schlegelmilch K, Russell RC, Yimlamai D, Basnet H, Mahadevan N, Fitamant J, et al. YAP mediates crosstalk between the Hippo and PI(3)K-TOR pathways by suppressing PTEN via miR-29. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1322–1329. doi: 10.1038/ncb2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anson M, Crain-Denoyelle AM, Baud V, Chereau F, Gougelet A, Terris B, Yamagoe S, et al. Oncogenic beta-catenin triggers an inflammatory response that determines the aggressiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:586–599. doi: 10.1172/JCI43937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oguma K, Oshima H, Aoki M, Uchio R, Naka K, Nakamura S, Hirao A, et al. Activated macrophages promote Wnt signalling through tumour necrosis factor-α in gastric tumour cells. The EMBO Journal. 2008;27:1671–1681. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kodama T, Takehara T, Hikita H, Shimizu S, Shigekawa M, Tsunematsu H, Li W, et al. Increases in p53 expression induce CTGF synthesis by mouse and human hepatocytes and result in liver fibrosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3343–3356. doi: 10.1172/JCI44957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lujambio A, Akkari L, Simon J, Grace D, Tschaharganeh DF, Bolden JE, Zhao Z, et al. Non-cell-autonomous tumor suppression by p53. Cell. 2013;153:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bard-Chapeau EA, Li S, Ding J, Zhang SS, Zhu HH, Princen F, Fang DD, et al. Ptpn11/Shp2 acts as a tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:629–639. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Broitman SA, Gottlieb LS, Zamcheck N. Influence of Neomycin and Ingested Endotoxin in the Pathogenesis of Choline Deficiency Cirrhosis in the Adult Rat. J Exp Med. 1964;119:633–642. doi: 10.1084/jem.119.4.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, Schwabe RF. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dapito DH, Mencin A, Gwak GY, Pradere JP, Jang MK, Mederacke I, Caviglia JM, et al. Promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by the intestinal microbiota and TLR4. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:504–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iliopoulos D, Jaeger SA, Hirsch HA, Bulyk ML, Struhl K. STAT3 Activation of miR-21 and miR-181b-1 via PTEN and CYLD Are Part of the Epigenetic Switch Linking Inflammation to Cancer. Molecular Cell. 2010;39:493–506. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, Ammann RW, Lankisch PG, Andersen JR, Dimagno EP, et al. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Pancreatitis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1433–1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cutrera J, Dibra D, Xia X, Hasan A, Reed S, Li S. Discovery of a linear peptide for improving tumor targeting of gene products and treatment of distal tumors by IL-12 gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2011;19:1468–1477. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guerra C, Collado M, Navas C, Schuhmacher AJ, Hernandez-Porras I, Canamero M, Rodriguez-Justo M, et al. Pancreatitis-induced inflammation contributes to pancreatic cancer by inhibiting oncogene-induced senescence. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:728–739. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee KE, Bar-Sagi D. Oncogenic KRas suppresses inflammation-associated senescence of pancreatic ductal cells. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:448–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.di Magliano MP, Logsdon CD. Roles for KRAS in pancreatic tumor development and progression. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1220–1229. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huang H, Daniluk J, Liu Y, Chu J, Li Z, Ji B, Logsdon CD. Oncogenic K-Ras requires activation for enhanced activity. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Daniluk J, Liu Y, Deng D, Chu J, Huang H, Gaiser S, Cruz-Monserrate Z, et al. An NF-kappaB pathway-mediated positive feedback loop amplifies Ras activity to pathological levels in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1519–1528. doi: 10.1172/JCI59743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ardito CM, Gruner BM, Takeuchi KK, Lubeseder-Martellato C, Teichmann N, Mazur PK, Delgiorno KE, et al. EGF receptor is required for KRAS-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:304–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Collins MA, Bednar F, Zhang Y, Brisset JC, Galban S, Galban CJ, Rakshit S, et al. Oncogenic Kras is required for both the initiation and maintenance of pancreatic cancer in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:639–653. doi: 10.1172/JCI59227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Charo C, Holla V, Arumugam T, Hwang R, Yang P, Dubois RN, Menter DG, et al. Prostaglandin E2 regulates pancreatic stellate cell activity via the EP4 receptor. Pancreas. 2013;42:467–474. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318264d0f8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Lee Kyoung E, Hajdu Cristina H, Miller G, Bar-Sagi D. Oncogenic Kras-Induced GM-CSF Production Promotes the Development of Pancreatic Neoplasia. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:836–847. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ling J, Kang Y, Zhao R, Xia Q, Lee DF, Chang Z, Li J, et al. KrasG12D-induced IKK2/beta/NF-kappaB activation by IL-1alpha and p62 feedforward loops is required for development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:105–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cutrera J, Dibra D, Satelli A, Xia X, Li S. Intricacies for posttranslational tumor-targeted cytokine gene therapy. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:378971. doi: 10.1155/2013/378971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]