Abstract

Objective

Phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP), which binds phospholipids and facilitates their transfer between lipoproteins in plasma, plays a key role in lipoprotein remodeling but its influence on nascent HDL formation is not known. The effect of PLTP over-expression on apoA-I lipidation by primary mouse hepatocytes was investigated.

Approach and Results

Over-expression of PLTP through an adenoviral vector markedly affected the amount and size of lipidated apoA-I species that were produced in hepatocytes in a dose-dependent manner, ultimately generating particles that were smaller than 7.1 nm but larger than lipid-free apoA-I. These < 7.1 nm small particles generated in the presence of over-expressed PLTP were incorporated into mature HDL particles more rapidly than apoA-I both in vivo and in vitro, and were less rapidly cleared from mouse plasma than lipid-free apoA-I. The < 7.1 nm particles promoted both cellular cholesterol and phospholipid efflux in an ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) dependent manner, similar to apoA-I in the presence of PLTP. Lipid-free apoA-I had a greater efflux capacity in the presence of PLTP than in the absence of PLTP, suggesting that PLTP may promote ABCA1-mediated cholesterol and phospholipid efflux. These results indicate that PLTP alters nascent HDL formation by modulating the lipidated species as well as promoting the initial process of apoA-I lipidation.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that PLTP exerts significant effects on apoA-I lipidation and nascent HDL biogenesis in hepatocytes by promoting ABCA1-mediated lipid efflux and the remodeling of nascent HDL particles.

Keywords: PLTP, HDL formation, cholesterol efflux, hepatocyte

Introduction

Phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) is a 476 residue glycoprotein with a molecular weight (MW) of 81 kDa. PLTP is expressed ubiquitously, including liver 1, 2 and small intestine.3 It is also highly expressed in macrophages 4, 5 and in atherosclerotic lesions. 6, 7 PLTP belongs to the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) binding/lipid transfer gene family that includes the LPS binding protein (LBP), the neutrophil bactericidal permeability increasing protein (BPI) and cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP).1 PLTP mediates the transfer of a variety of amphipathic molecules between lipoproteins, including diacylglyceride, phosphatidic acid, sphingomyelin (SM), phosphatidylcholine (PC), phosphatidylglycerol, cerobroside, phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) 8 and α-tocopherol.9 These transfer activities of PLTP have an important function in lipoprotein metabolism. The role of PLTP in atherogenesis remains uncertain, as do the underlying mechanisms.10 An atherogenic role of PLTP was initially suggested by studies of PLTP-deficient mice. In apoB-transgenic and apoE-deficient mice, PLTP deficiency markedly decreased atherosclerosis.11 This concept was supported by results of PLTP over-expression in mice lacking either apoE12, 13 or the LDL receptor,14 in which over-expression of PLTP increased atherosclerosis. However, a study has suggested that expression of PLTP in macrophages is atheroprotective in LDLR-deficient mice with systemic PLTP deficiency.15 The underlying mechanisms are unclear.

Plasma PLTP enhances the net transfer of phospholipids from VLDL to HDL and the exchange of phospholipids between VLDL and HDL. Both the transfer and the exchange activities of PLTP are stimulated by lipoprotein lipase induced lipolysis.16 Phospholipid exchange between VLDL and HDL may result in net transfer of certain molecular species of phospholipid into HDL and may play a role in providing substrate for lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT).16 PLTP is thought to serve as an HDL conversion factor by promoting the remodeling of HDL to form larger and smaller particles.17, 18 Triglyceride-enrichment of HDL enhances this conversion.19 Particle fusion is responsible for the enlargement of HDL particles.20 Concomitantly with the appearance of enlarged particles, lipid-poor apoA-I is released.21 The mechanism(s) involved in these processes and their exact physiological relevance remain poorly understood.

A key role for PLTP in vivo is evident in PLTP-deficient mice. These mice lack plasma transfer activities for PC, PE, phosphatidylinositol (PI), SM, and have reduced cholesterol transfer activity. The reduced plasma PLTP activity results in markedly decreased plasma HDL lipid and apolipoproteins, indicating the importance of the transfer of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRL) surface components in maintaining HDL levels.22 Liver-specific PLTP deficiency also significantly reduces plasma HDL and apoB-containing lipoprotein levels in mice, demonstrating the importance of hepatic PLTP in maintaining the lipoprotein levels.23 PLTP transgenic mice that overexpress human PLTP were shown, somewhat unexpectedly, to exhibit a modest but significant decrease (30% to 40%) in plasma HDL cholesterol.24 However, despite a lower HDL concentration, plasma from transgenic animals is much more efficient in preventing the accumulation of intracellular cholesterol in macrophages than plasma from wild-type mice, suggesting that PLTP contributes to HDL formation.24

The influence of PLTP on nascent HDL formation may be one of the mechanisms to explain the conflicting results in terms of the effect of PLTP on HDL levels. A role for PLTP in HDL production is suggested by the observation that primary PLTP-deficient hepatocytes produce less nascent HDL.23 The lipidated apoA-I secreted by PLTP-deficient hepatocytes contains less PC and SM, and differs also in its PC/SM ratio and fatty acyl species composition compared to lipidated apoA-I from WT hepatocytes.25 A number of studies have demonstrated that PLTP enhances cellular cholesterol and phospholipid efflux. Treatment of cholesterol-loaded human skin fibroblasts with PLTP increases HDL binding to cells and enhances cholesterol and phospholipid efflux.26 PLTP stabilizes ABCA1,27 and the absence of endogenous PLTP impairs ABCA1-dependent efflux of cholesterol from lipid-loaded macrophages.4 An amphipathic helical region of the N-terminal barrel of PLTP appears critical for ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux.28

In this study, we investigated the impact of PLTP over-expression on nascent HDL formation and remodeling by primary mouse hepatocytes. Our findings indicate that PLTP exerts significant effects on apoA-I lipidation and nascent HDL biogenesis in hepatocytes by promoting both ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux and nascent HDL particle remodeling.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Methods are available in the online-only Date Supplement.

Results

PLTP alters nascent HDL formation in hepatocytes

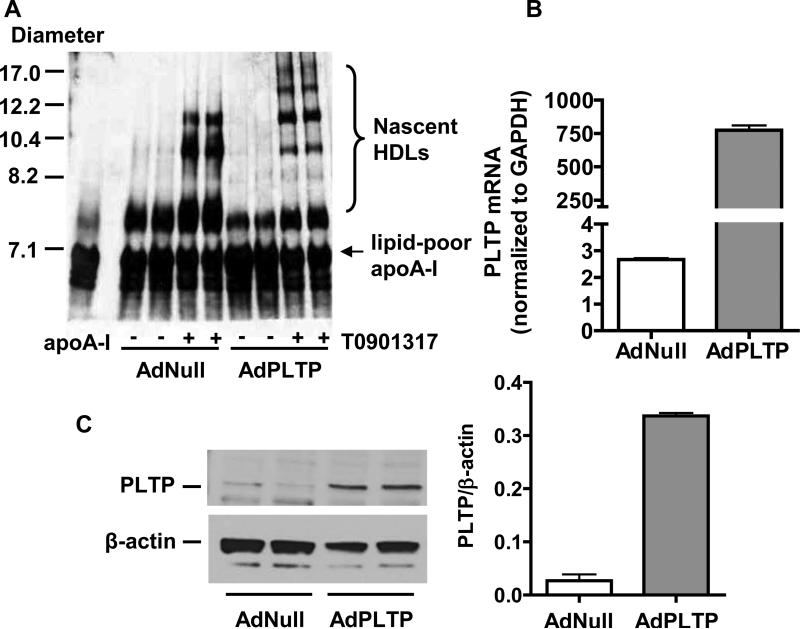

To investigate the effects of PLTP on nascent HDL formation in hepatocytes, primary hepatocytes were harvested 24 h after administration of adenovirus (AdPLTP) to mice. After overnight culture, cells were treated with the LXR agonist T0901317 (5 μM) for 8 h and then incubated for 16 h with lipid-free human apoA-I (10 μg/ml). Culture medium was then characterized by non-denaturing GGE and subsequent immunoblotting for human apoA-I (Fig. 1A). A marked over-expression of PLTP in hepatocytes was shown by real time PCR (Fig. 1B) and Western blot analysis (Fig. 1C). As expected, ABCA1 was expressed in hepatocytes and the LXR agonist increased ABCA1 expression. The expression of PLTP in hepatocytes did not significantly alter ABCA1 expression (Supplemental Fig. I).

Figure 1. PLTP alters nascent HDL formation in hepatocytes.

Primary hepatocytes were harvested 24 h after administration of AdPLTP adenovirus (4 × 10 10 particles) or AdNull control adenovirus (4 × 10 10 particles) to mice. After overnight culture, some of the cells were treated with 5 μM T0901317 in Williams’ Medium E containing 0.2% fatty acid-free BSA for 8 h and then incubated for 16 h with lipid-free human apoA-I (10 μg/ml) in medium containing 0.2% fatty acid-free BSA. An aliquot of 10 μl cell culture medium was characterized by non-denaturing GGE and subsequent immunoblot analysis for human apoA-I (Fig. 1A). The expression of PLTP in hepatocytes treated with 5 μM T0901317 was analyzed by real time PCR (Fig. 1B). PLTP protein expression in hepatocytes was determined by Western blot analysis of 10 μg cell protein and quantification was carried out by densitometric scanning (Fig. 1C).

Compared to the level of apoA-I lipidation with hepatocytes from AdNull control mice, the spectrum of nascent HDL particles produced by hepatocytes with PLTP over-expression was markedly changed. Over-expression of PLTP in hepatocytes affected the levels as well as the species of nascent HDL particles produced by hepatocytes. Although the formation of smaller nascent HDLs was reduced by PLTP, the formation of the larger HDLs was increased. These data demonstrate for the first time that PLTP affects nascent HDL biogenesis in addition to its role in mature HDL remodeling.

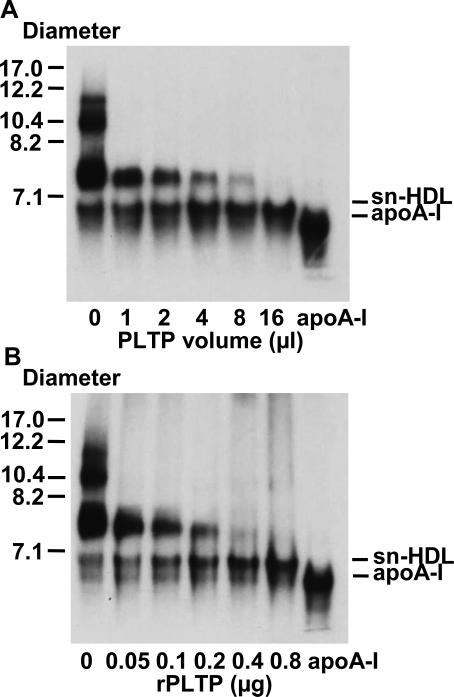

PLTP remodels nascent HDL particles in vitro

PLTP has been shown to remodel HDL by facilitating transfer of phospholipids between lipoprotein particles.16 PLTP can also serve as a putative fusion factor to enlarge HDL particles.17 However, the role of PLTP on nascent HDL remodeling is not clear. To study the effect of PLTP on pre-existing nascent HDL, nascent HDL particles were generated by incubating primary hepatocytes with 5 μg/ml human 125I-apoA-I for 24 h. Media containing these nascent HDL particles were then incubated in vitro with PLTP containing conditioned medium produced by COS-7 cells transfected with AdPLTP. The sample was subjected to the non-denaturing GGE and visualized by autoradiography. As shown in Fig. 2A, PLTP efficiently remodeled nascent HDLs in vitro in a dose dependent manner, ultimately generating small nascent HDL particles (sn-HDL) which were smaller than 7.1 nm but slightly larger than lipid-poor apoA-I. Nascent HDL remodeling was also carried out using recombinant mouse PLTP and yielded near identical results (Fig. 2B). The size difference between sn-HDL and apoA-I was also observed on gradient GGE gels which were run to equilibrium (3000 volt.h) (supplemental Fig. II). Similar results were obtained when apoA-I-containing species were analyzed by Western blotting (Supplemental Fig. III).

Figure 2. PLTP remodels nascent HDL particles in vitro.

Nascent HDL particles were generated by incubating primary hepatocytes with 5 μg/ml human 125I-apoA-I for 24 h. An aliquot (80 ng in 16 μl) of 125I-apoA-I lipidated particles was incubated with the indicated amount of COS-7 culture medium containing PLTP (activity = 15.4 pmole/μl/h) (Fig. 2A) or the indicated amount of recombinant mouse PLTP (activity = 338 pmole/μg/h) (Fig. 2B) for 16 h at 37°C. The samples were analyzed by non-denaturing GGE (4–20% acrylamide), and visualized by autoradiography.

Cholesterol efflux capacity of PLTP modified nascent HDL particles

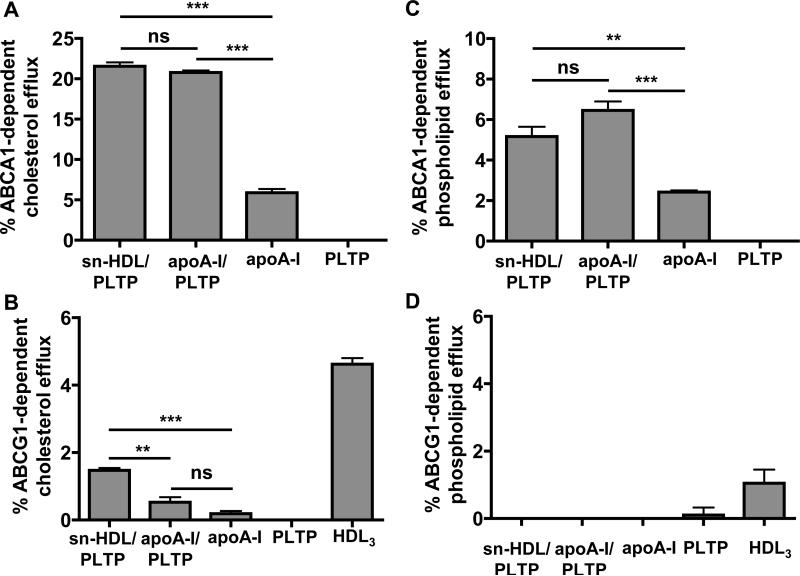

To determine the cellular cholesterol and phospholipid efflux capacity of the sn-HDL, BHK cells over-expressing human ABCA1 or ABCG1 were used. Cells were labeled with 0.2 μCi/ml [3H]cholesterol or 1 μCi/ml [3H]choline chloride for 48 h, then incubated for 24 h with cell medium containing sn-HDL or with apoA-I in medium with or without PLTP. Efflux of cellular [3H] cholesterol or [3H] phospholipid to medium was expressed as the percentage of total radioactivity in media and cells.

The sn-HDL particles promoted cellular cholesterol or phospholipid efflux in an ABCA1 dependent manner, similar to apoA-I in the presence of PLTP. ApoA-I had a greater efflux capacity in the presence of PLTP than in the absence of PLTP. PLTP alone did not promote cholesterol or phospholipid efflux (Fig. 3A, C). The sn-HDL served as a 15-fold better substrate for ABCA1-dependent efflux compared to ABCG1-dependent efflux. Nevertheless, the sn-HDL had a 3-fold greater capacity to promote ABCG1 dependent cholesterol efflux in the presence of PLTP than apoA-I (Fig. 3B). Neither sn-HDL nor apoA-I in the presence or absence of PLTP, promoted ABCG1-dependent phospholipid efflux, whereas HDL3 promoted ABCG1-dependent phospholipid efflux as expected (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3. Cholesterol and phospholipid efflux capacity of PLTP modified nascent HDL particles.

BHK cells over-expressing human ABCA1 (Fig. 3A, C) or ABCG1 (Fig. 3B, D) were used to determine cellular cholesterol (Fig. 3A, B) and phospholipid (Fig. 3C, D) efflux to sn-HDL. Cells were labeled with 0.2 μCi/ml [3H]cholesterol or 1μCi/ml [3H]choline chloride for 48 h, then incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 5 μg/ml sn-HDL or with 5 μg/ml apoA-I in the presence or absence of PLTP (activity = 15.4 pmole/μl/h), PLTP alone (15.4 pmole/μl/h), or 20 μg/ml HDL3. Efflux of cellular [3H] cholesterol or [3H] phospholipid to medium was expressed as the percentage of total radioactivity in the medium and cells together. ABCA1- and ABCG1-specific values were calculated as the difference between the efflux values in ABCA1 cells or ABCG1 cells and BHK control cells. Values shown were the mean ± SEM of triplicate determinations. Statistical analysis was done using unpaired, two-tailed t-tests. **: P < 0.01; ***: P < 0.001; ns: no significant difference.

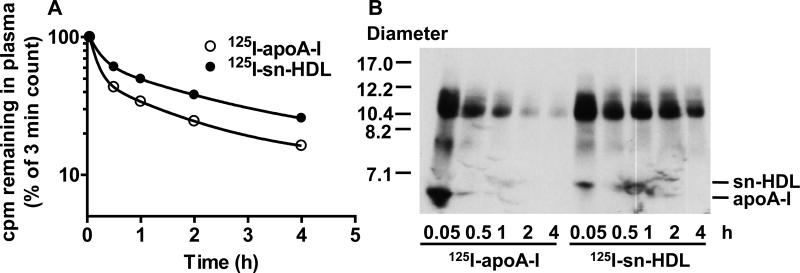

Plasma turnover of PLTP modified nascent HDL particles in human apoA-I transgenic mice

Previous reports have indicated that different sized nascent HDLs exhibit different plasma clearance rates.29 We next examined whether plasma clearance of sn-HDL in vivo differs from apoA-I. A tracer of 1.4 μg 125I-sn-HDL (approx. 1 × 106 cpm in 100 μl) in cell medium was injected via tail vein into a C57BL/6-Tg (APOA1) 1Rub/J mouse. This strain of mice was used since HDL in these animals contains very predominantly human A-I, and since apoA-I from human and mouse interact differently with HDL. An equivalent amount of 125I-apoA-I, pre-incubated with the same amount of PLTP-containing medium that was used to generate sn-HDL, was studied for comparison. At the selected intervals after tracer injection (3 min - 4 h), plasma samples were collected and 125I determined. At 4 h after tracer injection, the mice were humanely killed, and livers and kidneys were collected and radioassayed.

It is evident from the plasma clearance curves that clearance of 125I-sn-HDL was significantly slower (approximately 3-fold) compared with lipid-free apoA-I (Fig. 4A). The times taken to clear 50% of the injected doses of sn-HDL and apoA-I were 0.97 ± 0.014 h and 0.35 ± 0.017 h, p<0.0001, respectively. It is also evident that clearance of both ligands is biphasic with more rapid clearance of apoA-I than sn-HDL during both phases. Clearance of HDL apoA-I has been best described using a two pool model with a rapid initial phase being associated with an equilibration of ligand between the vascular and extravascular pools. An accurate determination of the fractional clearance rates of the two ligands will require a more extensive data set than shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4. Plasma turnover of PLTP modified nascent HDL particles in human apoA-I transgenic mice.

The tracer of 125I-sn-HDL or 125I-apoA-I (1.4 μg, approx. 1 × 10 6 cpm in 100 μl) pre-incubated with PLTP was injected via tail vein into C57BL/6-Tg (APOA1) 1Rub/J mice (n = 4). At the selected intervals after tracer injection (3 min-4 h), an aliquot of 10 μl plasma was radioassayed (Fig. 4A). An aliquot of 20 μl plasma was analyzed by nondenaturing GGE (4–20% acrylamide), and visualized by autoradiography (Fig. 4B).

Analysis of plasma samples by non-denaturing GGE demonstrated that injected 125I-sn-HDL was very rapidly incorporated into larger HDL-sized particles, and more rapidly than 125I-apoA-I (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, incorporated 125I-sn-HDL protein appeared to be less rapidly cleared from plasma than HDL-associated 125I-apoA-I. After 4 h of tracer injection, significant amounts of 125I-sn-HDL protein remained associated with HDL-sized particles, whereas the majority of 125I-apoA-I had been cleared from such particles. A more efficient incorporation of sn-HDL into HDL particles that have a slower clearance rate may contribute to its reduced plasma clearance compared to apoA-I. In contrast, 125I-apoA-I rapidly disappears from the unlipidated as well as the HDL-sized fraction. This suggests that the 125I-apoA-I association with HDL may be less firmly bound than in the case of 125I-sn-HDL, and might therefore contribute to its rapid clearance from plasma.

Since lipid-free and lipid-poor apoA-I has been shown to clear more rapidly from plasma than HDL, particularly through the kidney, the efficient association of sn-HDL with HDL in the plasma might therefore reduce its clearance rate as a result of reduced clearance by the kidney. To identify the possible tissue sites of clearance of apoA-I, livers and kidneys were removed from recipient mice 4 h after tracer injection and radiolabel content was determined as percentage of injected tracer. As shown in Supplemental Fig. IVA, B, 125I accumulation, in the kidney, but not in the liver, is greater for 125I-apoA-I than 125I-sn-HDL despite a lower plasma concentration of 125I-apoA-I. This suggests that reduced clearance of 125I-sn-HDL in the kidney may contribute to its slower rate of clearance compared to apoA-I. To substantiate this possibility, additional studies using a non-degradable modified apoA-I are required to quantify rates of tissue uptake of these ligands.

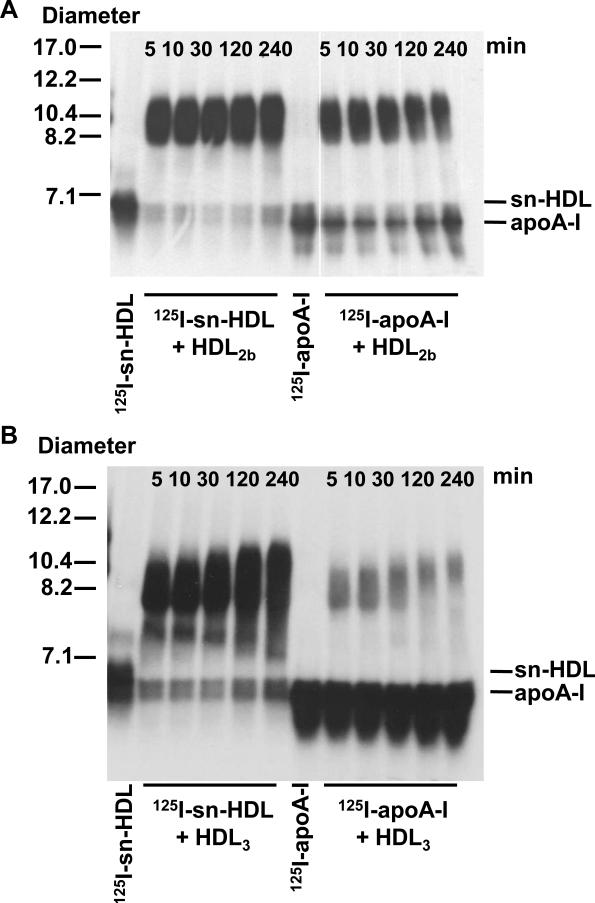

Remodeling of PLTP modified nascent HDL particles in vitro

Based on the data presented in Fig. 4B, sn-HDL appears to associate with circulating HDL in vivo. To examine the ability of sn-HDL to incorporate into HDL in vitro, 50 ng in 10 μl of cell medium containing 125I-sn-HDL or 125I-apoA-I, pretreated with equal volume of PLTP (15.4 pmole/μl/h), were incubated with 15 μg of unlabeled HDL2b or HDL3 for indicated times at 37°C (Fig. 5A, B). The reaction was analyzed by nondenaturing GGE and visualized by autoradiography.

Figure 5. Remodeling of PLTP modified nascent HDL particles in vitro.

An aliquot (50 ng in 10 μl) of sn-HDL or apoA-I pretreated with equal volume of COS-7 culture medium containing PLTP (activity = 15.4 pmole/μl/h) was incubated with 15 μg of HDL2b (Fig. 5A) or HDL3 (Fig. 5B) for indicated time period at 37°C. After incubation, the samples were applied to a non-denaturing GGE (4–20% acrylamide) and visualized by autoradiography.

The 125I-sn-HDL was rapidly associated with HDL2b or HDL3, as indicated by the migration of the vast majority of the radiolabel at a size corresponding to HDL after 5 min incubation. The association of 125I-sn-HDL to mature HDL particles appeared to be more complete and less reversible with time compared to 125I-apoA-I. After 4 h incubation, the majority of the 125I-sn-HDL remained associated with HDL2b or HDL3 (Fig. 5A, B), whereas almost half of the apoA-I was dissociated from HDL2b (Fig. 5A). In the case of HDL3, association of 125I-apoA-I was markedly less than for 125I-sn-HDL, and majority of 125I-apoA-I remained non-associated with HDL (Fig. 5B). These results indicated that compared to lipid-free apoA-I, the apoA-I of sn-HDL was either more readily incorporated into HDL or more effectively exchanged with apoA-I in HDL.

Discussion

PLTP plays a key role in HDL remodeling and function during physiological and pathophysiological conditions.10 Whether PLTP modulates the process of nascent HDL formation remains to be clarified. Since liver is the primary site for HDL biogenesis and a major source of PLTP expression, we investigated the effects of PLTP over-expression on nascent HDL formation and nascent HDL remodeling in primary mouse hepatocytes. We observed that hepatocyte over-expression of PLTP markedly affected the amount and size of lipidated apoA-I species that were produced, confirming a significant role of PLTP on HDL biogenesis and providing new insight into how PLTP influences HDL metabolism.

A role for PLTP in HDL production is evident by the observation that PLTP-deficient hepatocytes produced less nascent HDL.23 Conversely, recombinant PLTP promoted HDL formation in hepatocytes.23 However, how PLTP affects HDL production is not clear. We observed that PLTP over-expression in hepatocytes changed the spectrum of nascent HDL particles produced by hepatocytes. The formation of the larger HDL particles was increased by PLTP over-expression in hepatocytes (Fig. 1A). These results demonstrated that PLTP promoted the enlargement of nascent HDL particles. PLTP has been reported to enlarge mature HDL particles by inducing particle fusion. Such enlarged particles were not stable when injected intravenously into mice being rapidly cleared from the circulation.20, 21 The mechanism whereby PLTP produces larger nascent HDLs is not known but may, as for mature HDL remodeling, involve particle fusion.

We showed that PLTP altered nascent HDL formation in hepatocytes at least partly by remodeling lipidated apoA-I species after they were formed. The ability of PLTP to remodel nascent HDL particles was previously investigated by incubating nascent HDL particles with wild-type or PLTP-deficient mouse plasma.29 Incubation of pre-β HDLs in control plasma resulted in remodeling of pre-β1 and -2 particles to medium-sized HDL (8–10 nm) and remodeling of pre-β3 and -4 to small HDL (7–8 nm). Remodeling of all nascent pre-β HDL particles was significantly decreased in PLTP-deficient plasma compared with wild-type control plasma, suggesting that PLTP is necessary for remodeling of nascent pre-β HDL.29 To further examine the effects of PLTP on nascent HDL particle remodeling, we incubated the nascent HDL particles generated from control hepatocytes with PLTP in vitro. PLTP in cell-conditioned medium obtained from over-expressing COS cells and recombinant PLTP yielded similar results. As shown in Fig. 2, PLTP was able to modulate nascent HDL particles in vitro in a dose-dependent manner; ultimately generating particles that were smaller than 7.1 nm, but larger than apoA-I, from larger nascent HDLs. PLTP has been reported to release lipid-poor apoA-I from mature HDL particles during HDL remodeling process.21 Our results demonstrated that PLTP is capable of remodeling nascent HDL particles and releasing small apoA-I species (sn-HDL) from nascent HDLs.

To examine whether PLTP modulated an early step in nascent HDL formation, namely, cellular cholesterol efflux, BHK cells over-expressing human ABCA1 or ABCG1 were examined. PLTP did promote apoA-I induced cholesterol efflux in an ABCA1 dependent manner (Fig. 3A). These results demonstrated that PLTP is capable of enhancing apoAI lipidation by ABCA1. This is in line with previous studies that macrophage foam cells from PLTP-deficient mice released less cholesterol to lipid-free apoA-I and to HDL than did the corresponding WT foam cells,4 suggesting the involvement of PLTP in cellular cholesterol efflux. It has also been reported that PLTP interaction with ABCA1 stabilizes the transporter, suggesting the significance of PLTP in ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux.27, 28 It is possible that PLTP may function through its ability to transfer phospholipids and this notion is in line with our results showing that PLTP does promote the efflux of phospholipids to apoA-I, in addition to cholesterol efflux.

To examine the possible physiological effects of PLTP modification on nascent HDL function, we determined the efflux capacity of sn-HDL that are generated by the action of PLTP on nascent HDLs. As shown in Fig. 3A, these particles promoted cellular cholesterol efflux in an ABCA1-dependent manner to similar extent as apoA-I. The cholesterol efflux induced by PLTP modified particles was more ABCA1 dependent than ABCG1 dependent; however, sn-HDL had a greater capacity to promote ABCG1-dependent cholesterol efflux than apoA-I (Fig. 3B). ABCA1 was recognized as the principal molecule involved in cholesterol efflux to apoA-I from macrophage foam cells. 30 In addition to ABCA1, another ABC transporter, ABCG1, has been shown to contribute to cholesterol efflux to HDL from macrophages.31 A synergistic relationship between ABCA1 and ABCG1 in promoting cholesterol efflux has been proposed.32, 33 The nascent HDL particles generated through ABCA1 action were shown to function as efficient acceptors for ABCG1-mediated cholesterol efflux.32, 33 In the present study, we demonstrated that PLTP-modified nascent HDL particles had a greater capacity to promote ABCG1-dependent cholesterol efflux than apoA-I, suggesting a role of PLTP in the synergistic effect of ABCA1 and ABCG1 in promoting cellular cholesterol efflux. The functional properties of sn-HDL in mediating cholesterol efflux through the different cholesterol transporters are very consistent with a minimal but significant lipidation of apoA-I in sn-HDL. Together with increased size of sn-HDL and its altered capacity to associate with HDL, these results strongly support a lipidated state of apoA-I in sn-HDL.

To study the possible metabolic fate of these small PLTP-generated species in vivo, we injected 125I-labeled sn-HDL into human apoA-I transgenic mice to assess the plasma turnover rate of these small particles in comparison with lipid-free apoA-I. As shown in Fig. 4, in the presence of PLTP, the plasma clearance of sn-HDL was significantly slower compared to that of apoA-I. We also demonstrated that these small particles were rapidly remodeled to mature HDL-sized particles both in vivo and in plasma ex vivo, likely by fusion with pre-existing HDL (Figs. 4, 5). Such remodeling of sn-HDL occurred more effectively than the remodeling of lipid-free apoA-I. Remodeling of sn-HDL resulted in particles that appeared to be less rapidly cleared in vivo than lipid-free apoA-I or particles generated from lipid-free apoA-I. It is possible that the remodeling observed involved apoA-I exchange between sn-HDL and pre-existing HDL rather than a net transfer of sn-HDL onto plasma HDL. Perhaps more likely, given the relatively small size and predicted low lipid content of sn-HDL, remodeling involved the displacement of apoA-I from HDL by sn-HDL. It is likely that the structure and composition of nascent HDL particles, as well as their interaction with plasma factors, including PLTP, have a significant impact on the extent to which apoA-I is liberated from HDL. Overall, the results do provide clear evidence that snHDL is subject to increased remodeling and decreased plasma turnover compared to lipid-poor apoA-I. It is generally accepted that nascent HDLs acquire unesterified cholesterol and associate with LCAT, leading to cholesterol esterification and their conversion to mature HDL.34 Our studies provide evidence for another mechanism by which nascent HDLs can enter the mature HDL pool that is enhanced by PLTP-mediated particle remodeling.

Our findings suggest that PLTP exerts significant effects on apoA-I lipidation and nascent HDL biogenesis in hepatocytes by promoting ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux and the remodeling of nascent HDL particles.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Plasma high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol is an important negative risk factor for coronary heart disease. A key cardioprotective function of HDL is the delivery of cholesterol from tissues and plasma to the liver for secretion via the reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) pathway. The levels and composition of HDL subclasses in plasma are regulated by many factors, including phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP). PLTP, which binds phospholipids and facilitates their transfer between lipoproteins in plasma, plays a key role in HDL remodeling but its influence on nascent HDL formation is not known. The effect of PLTP on apoA-I lipidation and nascent HDL formation by primary mouse hepatocytes was investigated. Findings suggest that PLTP exerts significant effects on the processes of hepatic apoA-I lipidation and nascent HDL biogenesis by promoting ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux and the remodeling of nascent HDL particles.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Xuebing Wang and Victoria Noffsinger for excellent technical support. AdPLTP, an adenoviral vector encoding mouse phospholipid transfer protein was generously provided by Dr. J. L. Goldstein. The ABCA1 antibody was generously provided by Dr M. R. Hayden. BHK cells expressing human ABCA1 or human N-terminal FLAG-tagged ABCG1 were a generous gift from Dr. J. F. Oram.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Program Project Grant (PO1HL086670) to D. R. van der Westhuyzen and VA CSR&D MERIT REVIEW AWARD (1l01CX000773) to N. R. Webb.

Abbreviations

- ABCA1

ATP-binding cassette transporter A1

- ABCG1

ATP-binding cassette transporter G1

- apoA-I

apolipoprotein A-I

- BHK

Baby hamster kidney cell

- BPI

bactericidal permeability increasing protein

- CE

cholesteryl esters

- CETP

cholesteryl ester transfer protein

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- EL

endothelial lipase

- GGE

gradient gel electrophoresis

- HDL

high density lipoprotein

- LCAT

lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase

- LBP

lipopolysaccharide binding protein

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- LXR

liver X receptor

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- PI

phosphatidylinositol

- PLTP

Phospholipid transfer protein

- SAA

serum amyloid A

- SM

sphingomyelin

- sn-HDL

small nascent HDL

- TG

triglyceride

- TRL

triglyceride-rich lipoproteins

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Disclosures: none

References

- 1.Day JR, Albers JJ, Lofton-Day CE, Gilbert TL, Ching AF, Grant FJ, O'Hara PJ, Marcovina SM, Adolphson JL. Complete cdna encoding human phospholipid transfer protein from human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9388–9391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang XC, Bruce C. Regulation of murine plasma phospholipid transfer protein activity and mrna levels by lipopolysaccharide and high cholesterol diet. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17133–17138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu R, Iqbal J, Yeang C, Wang DQ, Hussain MM, Jiang XC. Phospholipid transfer protein-deficient mice absorb less cholesterol. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2014–2021. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.149914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee-Rueckert M, Vikstedt R, Metso J, Ehnholm C, Kovanen PT, Jauhiainen M. Absence of endogenous phospholipid transfer protein impairs abca1-dependent efflux of cholesterol from macrophage foam cells. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1725–1732. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600051-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valenta DT, Ogier N, Bradshaw G, Black AS, Bonnet DJ, Lagrost L, Curtiss LK, Desrumaux CM. Atheroprotective potential of macrophage-derived phospholipid transfer protein in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice is overcome by apolipoprotein ai overexpression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1572–1578. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000225700.43836.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desrumaux CM, Mak PA, Boisvert WA, Masson D, Stupack D, Jauhiainen M, Ehnholm C, Curtiss LK. Phospholipid transfer protein is present in human atherosclerotic lesions and is expressed by macrophages and foam cells. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1453–1461. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200281-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Brien KD, Vuletic S, McDonald TO, Wolfbauer G, Lewis K, Tu AY, Marcovina S, Wight TN, Chait A, Albers JJ. Cell-associated and extracellular phospholipid transfer protein in human coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2003;108:270–274. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000079163.97653.CD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao R, Albers JJ, Wolfbauer G, Pownall HJ. Molecular and macromolecular specificity of human plasma phospholipid transfer protein. Biochemistry. 1997;36:3645–3653. doi: 10.1021/bi962776b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kostner GM, Oettl K, Jauhiainen M, Ehnholm C, Esterbauer H, Dieplinger H. Human plasma phospholipid transfer protein accelerates exchange/transfer of alpha-tocopherol between lipoproteins and cells. Biochem J. 1995;305(Pt 2):659–667. doi: 10.1042/bj3050659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albers JJ, Vuletic S, Cheung MC. Role of plasma phospholipid transfer protein in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821:345–357. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang XC, Qin S, Qiao C, Kawano K, Lin M, Skold A, Xiao X, Tall AR. Apolipoprotein b secretion and atherosclerosis are decreased in mice with phospholipid-transfer protein deficiency. Nat Med. 2001;7:847–852. doi: 10.1038/89977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Haperen R, van Gent T, van Tol A, de Crom R. Elevated expression of pltp is atherogenic in apolipoprotein e deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2013;227:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang XP, Yan D, Qiao C, Liu RJ, Chen JG, Li J, Schneider M, Lagrost L, Xiao X, Jiang XC. Increased atherosclerotic lesions in apoe mice with plasma phospholipid transfer protein overexpression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1601–1607. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000085841.55248.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moerland M, Samyn H, van Gent T, van Haperen R, Dallinga-Thie G, Grosveld F, van Tol A, de Crom R. Acute elevation of plasma pltp activity strongly increases pre-existing atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1277–1282. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.165084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valenta DT, Bulgrien JJ, Bonnet DJ, Curtiss LK. Macrophage pltp is atheroprotective in ldlr-deficient mice with systemic pltp deficiency. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:24–32. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700228-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tall AR, Krumholz S, Olivecrona T, Deckelbaum RJ. Plasma phospholipid transfer protein enhances transfer and exchange of phospholipids between very low density lipoproteins and high density lipoproteins during lipolysis. J Lipid Res. 1985;26:842–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jauhiainen M, Metso J, Pahlman R, Blomqvist S, van Tol A, Ehnholm C. Human plasma phospholipid transfer protein causes high density lipoprotein conversion. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:4032–4036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tu AY, Nishida HI, Nishida T. High density lipoprotein conversion mediated by human plasma phospholipid transfer protein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23098–23105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rye KA, Jauhiainen M, Barter PJ, Ehnholm C. Triglyceride-enrichment of high density lipoproteins enhances their remodelling by phospholipid transfer protein. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:613–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korhonen A, Jauhiainen M, Ehnholm C, Kovanen PT, Ala-Korpela M. Remodeling of hdl by phospholipid transfer protein: Demonstration of particle fusion by 1h nmr spectroscopy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;249:910–916. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lusa S, Jauhiainen M, Metso J, Somerharju P, Ehnholm C. The mechanism of human plasma phospholipid transfer protein-induced enlargement of high-density lipoprotein particles: Evidence for particle fusion. Biochem J. 1996;313(Pt 1):275–282. doi: 10.1042/bj3130275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang XC, Bruce C, Mar J, Lin M, Ji Y, Francone OL, Tall AR. Targeted mutation of plasma phospholipid transfer protein gene markedly reduces high-density lipoprotein levels. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:907–914. doi: 10.1172/JCI5578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yazdanyar A, Quan W, Jin W, Jiang XC. Liver-specific phospholipid transfer protein deficiency reduces high-density lipoprotein and non-high-density lipoprotein production in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2058–2064. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Haperen R, van Tol A, Vermeulen P, Jauhiainen M, van Gent T, van den Berg P, Ehnholm S, Grosveld F, van der Kamp A, de Crom R. Human plasma phospholipid transfer protein increases the antiatherogenic potential of high density lipoproteins in transgenic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1082–1088. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.4.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siggins S, Bykov I, Hermansson M, Somerharju P, Lindros K, Miettinen TA, Jauhiainen M, Olkkonen VM, Ehnholm C. Altered hepatic lipid status and apolipoprotein a-i metabolism in mice lacking phospholipid transfer protein. Atherosclerosis. 2007;190:114–123. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wolfbauer G, Albers JJ, Oram JF. Phospholipid transfer protein enhances removal of cellular cholesterol and phospholipids by high-density lipoprotein apolipoproteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1439:65–76. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oram JF, Wolfbauer G, Vaughan AM, Tang C, Albers JJ. Phospholipid transfer protein interacts with and stabilizes atp-binding cassette transporter a1 and enhances cholesterol efflux from cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52379–52385. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oram JF, Wolfbauer G, Tang C, Davidson WS, Albers JJ. An amphipathic helical region of the n-terminal barrel of phospholipid transfer protein is critical for abca1-dependent cholesterol efflux. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:11541–11549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800117200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mulya A, Lee JY, Gebre AK, Boudyguina EY, Chung SK, Smith TL, Colvin PL, Jiang XC, Parks JS. Initial interaction of apoa-i with abca1 impacts in vivo metabolic fate of nascent hdl. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:2390–2401. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800241-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oram JF, Lawn RM, Garvin MR, Wade DP. Abca1 is the camp-inducible apolipoprotein receptor that mediates cholesterol secretion from macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34508–34511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Klucken J, Buchler C, Orso E, Kaminski WE, Porsch-Ozcurumez M, Liebisch G, Kapinsky M, Diederich W, Drobnik W, Dean M, Allikmets R, Schmitz G. Abcg1 (abc8), the human homolog of the drosophila white gene, is a regulator of macrophage cholesterol and phospholipid transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:817–822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gelissen IC, Harris M, Rye KA, Quinn C, Brown AJ, Kockx M, Cartland S, Packianathan M, Kritharides L, Jessup W. Abca1 and abcg1 synergize to mediate cholesterol export to apoa-i. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:534–540. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000200082.58536.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaughan AM, Oram JF. Abca1 and abcg1 or abcg4 act sequentially to remove cellular cholesterol and generate cholesterol-rich hdl. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2433–2443. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600218-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bailey D, Ruel I, Hafiane A, Cochrane H, Iatan I, Jauhiainen M, Ehnholm C, Krimbou L, Genest J. Analysis of lipid transfer activity between model nascent hdl particles and plasma lipoproteins: Implications for current concepts of nascent hdl maturation and genesis. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:785–797. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M001875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.