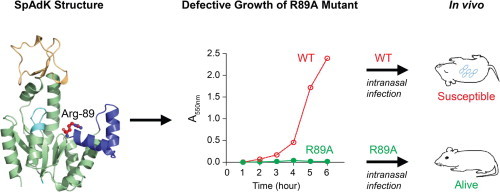

Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: SpAdK, Streptococcus pneumoniae adenylate kinase; Ap5A, adenosine pentaphosphate

Keywords: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Adenylate kinase, Crystal structure, Bacteria growth, Virulence factor

Highlights

-

•

Crystal structure of adenylate kinase from Streptococcus pneumoniae was determined.

-

•

Arg-89 was identified as a key residue for enzymatic activity.

-

•

Expression of the R89A mutated protein did not rescue a pneumococcal growth defect.

-

•

Lack of functional adenylate kinase caused a growth defect in vivo.

-

•

Pneumoccocal adenylate kinase is essential for growth both in vitro and in vivo.

Abstract

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) infection causes more than 1.6 million deaths worldwide. Pneumococcal growth is a prerequisite for its virulence and requires an appropriate supply of cellular energy. Adenylate kinases constitute a major family of enzymes that regulate cellular ATP levels. Some bacterial adenylate kinases (AdKs) are known to be critical for growth, but the physiological effects of AdKs in pneumococci have been poorly understood at the molecular level. Here, by crystallographic and functional studies, we report that the catalytic activity of adenylate kinase from S.pneumoniae (SpAdK) serotype 2 D39 is essential for growth. We determined the crystal structure of SpAdK in two conformations: ligand-free open form and closed in complex with a two-substrate mimic inhibitor adenosine pentaphosphate (Ap5A). Crystallographic analysis of SpAdK reveals Arg-89 as a key active site residue. We generated a conditional expression mutant of pneumococcus in which the expression of the adk gene is tightly regulated by fucose. The expression level of adk correlates with growth rate. Expression of the wild-type adk gene in fucose-inducible strains rescued a growth defect, but expression of the Arg-89 mutation did not. SpAdK increased total cellular ATP levels. Furthermore, lack of functional SpAdK caused a growth defect in vivo. Taken together, our results demonstrate that SpAdK is essential for pneumococcal growth in vitro and in vivo.

1. Introduction

Streptococcus pneumoniae (the pneumococcus), an encapsulated Gram-positive, causes life-threatening infections (pneumonia, bacteremia, meningitis), and claims more than 1.6 million deaths worldwide per year [1]. Streptococcal virulence is mediated by many cell-surface virulence factors including capsular polysaccharides and proteins as well as intracellular pneumolysin [2]. Nevertheless, survival and growth of pneumococci are prerequisites for virulence.

ATP is involved in many cellular metabolic processes as a major energy source, and could be a modulating factor for virulence [3]. Availability of the energy levels to living cells is dictated by adenine nucleotide homeostasis. Thus, rigorous control of adenine nucleotide homeostasis is crucial to cellular metabolism. Adenylate energy charge (EC) in living cells is definded as follows [4]:

EC is the amount of energy readily accessible for cellular metabolism [4,5] that may affect other fundamental pathogenesis such as bacterial growth, virulence factors, and secretion pathways [6,7].

Adenylate kinase (AdK; ATP:AMP phosphotransferase; EC 2.7.4.3) catalyzes conversion between adenylate nucleotides [8]: Mg. ATP + AMP ↔ Mg. ADP + ADP. AdK has been attributed to the synthesis and maintenance of adenine nucleotide homeostasis, which is crucial in cellular viability and cell energy [8]. In Escherichia coli, AdK is essential to cellular growth and survival, for regulation of adenine nucleotide homeostasis [9]. However, it has remained elusive as to whether AdK is essential in Gram-positive bacteria. To explore the possibility that AdK from S. pneumoniae (SpAdK) is crucial in pneumococcal growth by its catalytic activity, we have undertaken structural and functional studies on SpAdK, and investigated the effect of SpAdK on pneumococcal growth.

2. Results

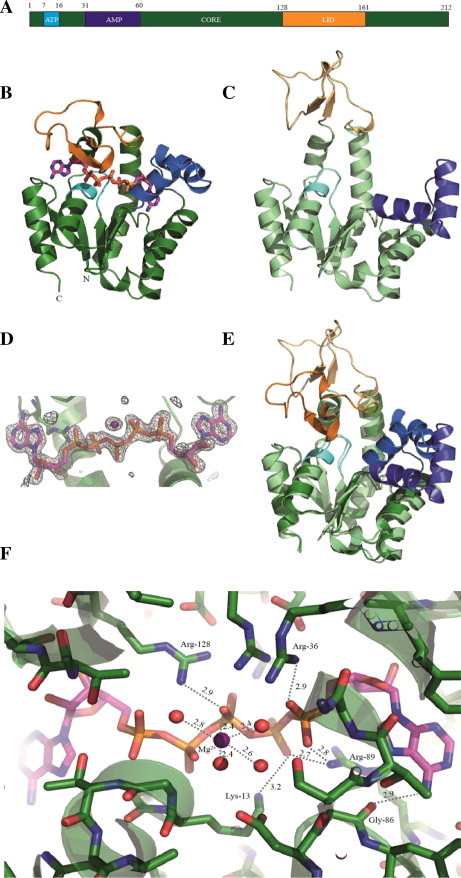

2.1. Crystal structure of adenylate kinase from S. pneumoniae in two conformations

SpAdK consists largely of core, nucleotide binding and lid domains (Fig. 1A). The nucleotide-binding domain is further divided into ATP and AMP binding domains. The crystal structures of SpAdK were determined in two conformations: inhibitor-bound closed form at 1.48 Å, and ligand-free, open form at 1.69 Å resolution (Fig. 1B and C). Both structures were deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession codes PDB: 4NU0 (closed structure with Ap5A) and PBD: 4NTZ (open structure).The overall folding of SpAdK features a typical α/β class structure, where α-helices wrap around a central β-sheet region (Figs. 1B and C). The lid and core domains, as well as P-loop, form an ATP binding pocket; meanwhile, AMP binds to the pocket formed by the core and AMP domains. The lid and AMP domains can access the substrate-binding site in the open form, which is consistent with previous reports [10,11]. P1, P5-di(adenosine-5′) pentaphosphate (Ap5A), a two-substrate mimicking inhibitor, was well defined in the closed conformation (Fig. 1D). Structural comparison between the two conformations showed significant changes, in which both the lid and AMP domains move closer to the active site, allowing substrate access, in reference to the core domain (Fig. 1E). Superposition of each domain between the two conformations revealed that the lid domain shows the most variation, with 1.6 Å of r.m.s.d., supporting domain movement.

Fig. 1.

Overview of SpAdK structure in two conformations. (A) SpAdK structure and its domains. (B) the crystal structure of SpAdK in complex with two mimic-substrates (Ap5A); the ATP, AMP, LID and CORE domains are colored with cyan, marine, orange and forest, respectively; Ap5A is shown by stick-view. (C) The crystal structure of native SpAdK, with ATP (light cyan), AMP (light blue), LID (light orange) and CORE (light green) domains. (D) The 2mFo-DFc electron density map at 1.48 A° resolution shows the Ap5A and cofactor Mg2+ (magenta sphere). (E) Superposition of two structures. (F) An insight view of the two mimic-substrate-binding cleft, including Mg2+ (magenta sphere), and 4 water molecules (red spheres). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

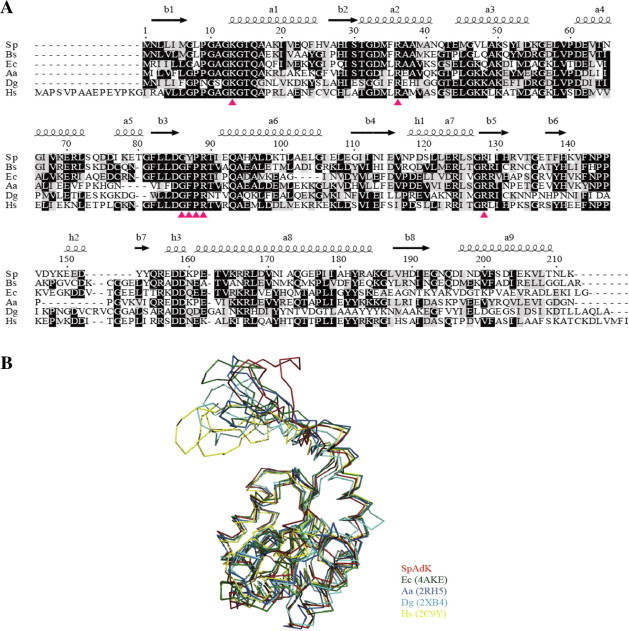

2.2. Structural comparison to known bacterial AdKs

The overall SpAdK structure is similar to those of other AdKs, with noticeable differences in the lid domain (Fig. 2). The superposition of open conformation structures from SpAdK, E. coli (Ec), Aquifex aeolicus (Aa), Desulfovibrio gigas (Dg), and Homo sapiens (Hs) using Dali server [12] showed significant differences in the higher mobile loops in the lid domain (Fig. 2A). For instance, the r.m.s.d. between Cα atoms from SpAdK and 4AKE (E. coli) structure is 3.2 Å. The number of residues in the lid domain is also different from other AdKs. Consistently, the sequence alignment from SpAdK and other AdKs shows the N-terminal region including P-loop (residues 7–16) is strictly conserved, whereas the lid domain and C-terminal region are variable (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, SpAdK does not contain a conserved metal-binding motif (Cys-X2-Cys-X16-Cys) in the lid domain [13].

Fig. 2.

(A) Secondary structure-based sequence alignment. (B) Structural superposition of SpAdK with AdKs from Bacillus subtilis (Bs), Escherichia coli (Ec); Aquifex aeolicus (Aa); Desulfovibrio gigas (Dg) and Homo sapiens (Hs). Conserved residues are labeled in black; arrows indicate the site-directed mutagenesis points.

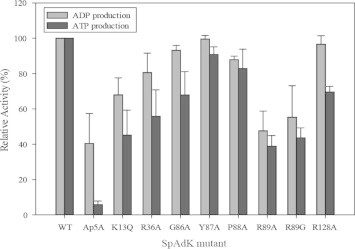

2.3. Arg-89 is the most important residue for catalytic activity

The active site of SpAdK features several conserved Arg residues (Fig. 1F). The strictly conserved Arg-89 forms hydrogen bonds with oxygen atoms, in both the δ- and ε-phosphate group of Ap5A. The ε-phosphate group of Ap5A corresponds to the phosphate group of AMP. The hydrogen bond network among Arg-89, Glu-93, and Asp-61 is known to serve as a backbone in the catalysis and AMP domain rearrangements [14]. Moreover, Arg-89 is a part of the conserved G(Y/F)PR motif stabilizing AdK structure, and transferring a phosphate group from ATP to AMP [15]. Two other Arg residues, Arg-36 and Arg-128 form hydrogen bonds with oxygen atoms of the phosphate groups in Ap5A. Gly-86 recognizes adenine base of Ap5A, by forming hydrogen bond with N6β. Tyr-87 is roughly parallel to an adenine moiety of Ap5A, without apparent hydrogen bond formation. Magnesium ion is found to be coordinated by four water molecules, as well as oxygen atoms from the β- and γ-phosphate of Ap5A, in the active site of the closed SpAdK:Ap5A structure. Lys-13 is located in the P-loop, and known to form hydrogen bonds with oxygen atoms from the phosphate groups of ATP and AMP [15]. In our SpAdK:Ap5A structure, Nζ forms a hydrogen bond with oxygen atom from the δ-phosphate group of Ap5A (3.2 Å), but is a little bit distant from the O3γ of Ap5A (3.9 Å) for hydrogen bonding to occur.

To assess the catalytic roles of the active site residues, the catalytic activities of eight SpAdK mutated proteins were measured (Fig. 3). Since AdKs catalyze both ATP formation and hydrolysis [16], the catalytic activities of both directions were measured. Among the mutated proteins tested, mutation at Arg-89 most significantly deteriorated the activity. We tested both R89A and R89G, because previous studies suggested that mutating Arg to Ala or Gly was efficient, in reducing the catalytic activity [17,18]. For SpAdK, both R89A and R89G exhibited comparable reduction in activity. Since all the eight residues subject to mutagenesis were mutated to Ala, we used R89A for subsequent functional studies. Taken together, our results establish that Arg-89 is a critical residue for the catalytic activity of SpAdK.

Fig. 3.

Activity assay of SpAdK mutated proteins. ADP production assay (black bars) and ATP production assay (tilted gray bars) are shown. One-letter amino acid codes are used. Relative activities in reference to the wild type (WT) are shown.

2.4. SpAdK deficiency abolishes pneumococcal growth

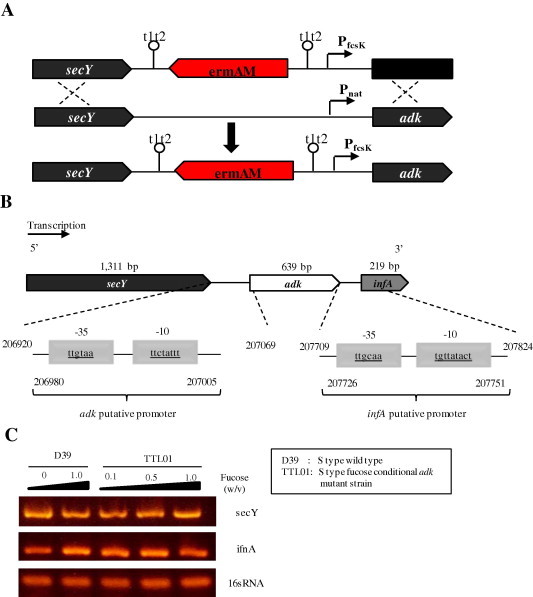

To determine the role of SpAdK in pneumococcal growth, we generated adk mutant, in either serotype 2 encapsulated D39 (S type), or non-encapsulated CP1200 (R type). However, these adk mutant strains were not viable, implying that SpAdK protein is essential. Hence, we generated a fucose-inducible strain, which permits conditional expression of adk in S. pneumoniae. We fused a fucose promoter with the adk open reading frame, thus expressing adk gene only in the presence of fucose (Fig. 4 and Table 2). In S. pneumoniae D39, the adk gene (spd_0214) is flanked by upstream secY (spd_0213) and by downstream infA (spd_0215) genes. The 639 bp of the adk open reading frame is flanked by 150 bp and 118 bp intergenic regions at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively. Transcription of the adk is not affected by the upstream gene secY nor the erythromycin resistance cassette (ermAM) owing to the transcription terminators at up- and down-stream of the adk gene to prevent transcription from either end (Fig. 4A). A bacterial σ70 promoter recognition program, BPROM [19], showed that putative promoters of the secY, adk, and infA genes are located in the upstream of these genes in the same orientation (Fig. 4B), suggesting that the adk and infA genes are transcribed independently. To confirm that fucose could regulate only adk transcription and not the flanking genes, total RNA was extracted in the presence of various concentrations of fucose and used for determination of mRNA level of the flanking genes by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR). RT-PCR data showed that secY and ifnA expression was not affected by fucose concentration (Fig. 4C), suggesting that fucose induces specifically adk expression but not its flanking genes and adk transcription does not affect expression of the flanking genes. Therefore, in our experimental system, adk was transcribed as a monocistronic.

Fig. 4.

Schematic of an inducible strain construction, adk locus and transcription. (A) Construction of S. pneumoniae type 2 adk fucose-inducible strain. (B) adk locus map. Putative promoters of secY, adk, and infA are found at the upstream region. Only putative promoters of adk and infA are shown. (C) mRNA level of the secY and ifnA genes was determined by RT-PCR analyses. Transcription of the adk flanking genes (secY and ifnA genes) was independent from the adk promoter.

Table 2.

Pneumococcal strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Strains plasmids | Relevant characteristics | Antibiotic resistance | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strains | |||

| D39 | Encapsulated, type 2 | [39] | |

| TTL01 | D39 PfcsK::adk | ERY | This study |

| TTL02 | TTL01 containing pMV158-adk | ERY, TET | This study |

| TTL03 | TTL01 containing pMV158-adk-R89A | ERY, TET | This study |

| CP1200 | Non-encapsulated derivative of Rx1 malM511-str1 | [38] | |

| TTL04 | CP1200 PfcsK::adk | ERY | This study |

| TTL05 | TTL02 containing pMV15-adk | ERY, TET | This study |

| TTL06 | TTL02 containing pMV158-adk-R89A | ERY, TET | This study |

| Plasmids | |||

| pMV158 | 5300 bp, streptococcal plasmid | TET | [43] |

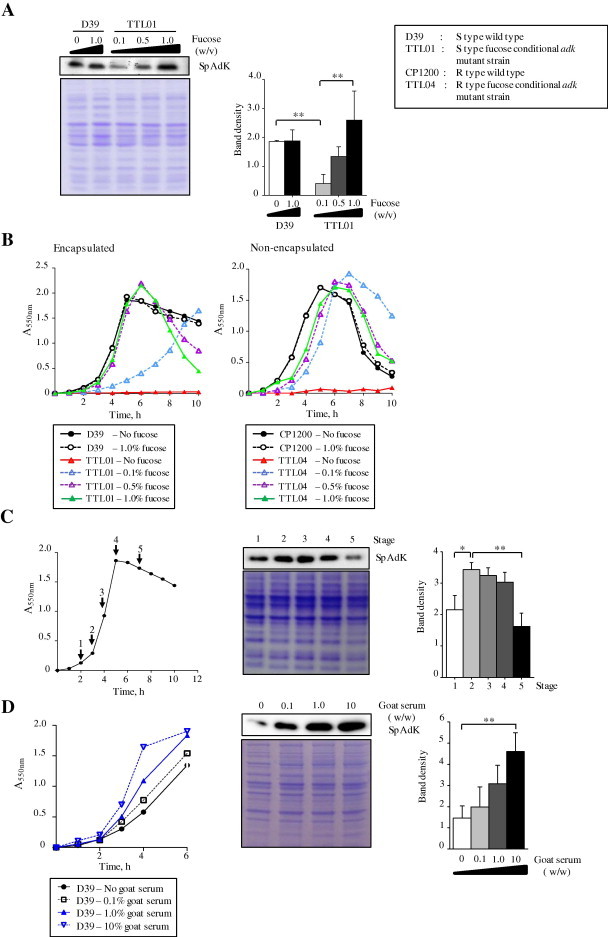

We examined the effect of adk expression on pneumococcal growth using the aforementioned fucose-inducible expression system (Fig. 5). In the absence of l-(−)-fucose (fucose), pneumococcal growth was arrested. However, after supplementation of various concentrations of fucose into the culture, a good correlation between fucose concentration and level of the SpAdK was demonstrated (Fig. 5A). Higher fucose concentration gave rise to higher growth rate in the fucose-inducible strains, while the growth rates of both S (encapsulated) and R (non-encapsulated) wild-types (WTs) were not affected by the presence of fucose (Fig. 5B). At 0.1% fucose concentration where the expression level of adk is low, encapsulated D39 fucose-inducible adk strain (TTL01) showed lower growth rate (Fig. 5B-left), than the non-encapsulated CP1200 adk mutant (TTL04) (Fig. 5B-right). This observation implies that 0.1% fucose could generate enough ATP for R type mutant for growth, but not for S type mutant. We speculate that at 0.1% fucose, S type TTL01 could not produce enough ATP for growth, most likely due to the requirement of ATP for capsular polysaccharide synthesis. This result supports that SpAdK is essential for growth. Notably, SpAdK expression was also higher at log-phase, than the other phases (Fig. 5C), which supports the idea that SpAdK provides ATP for cellular activities. Supplementation of goat serum induced SpAdK level dose-dependently and pneumococcal growth (Fig. 5D), strongly implying the relationship between SpAdK expression and pneumococcal growth.

Fig. 5.

Growth of fucose-inducible adk strain. (A) Fucose-dependent SpAdK induction in the TTL01, but not in D39 WT, at exponential phase. (B) Growth of D39 WT, TTL01 (left), and CP1200, TTL04 (right), in the presence of various fucose concentrations. (C) Growth-phase specific induction of SpAdK. (D) Dose-dependent induction of SpAdK by goat serum.

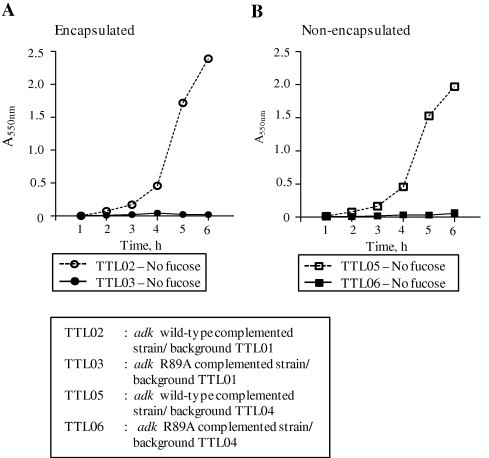

To further confirm the role of SpAdK in pneumococcal growth, pMV158 containing the WT adk gene or adk-R89A mutation was introduced into the adk inducible strains, and the requirement of SpAdK for growth was analyzed. When the WT adk gene was introduced into the adk inducible strains of S type (TTL01) and R type (TTL04), the resulting complemented strains (TTL02 and TTL05, respectively) resumed growth in the absence of fucose. In contrast, introduction of the R89A mutation to the adk inducible strains (TTL03 and TTL06) showed growth defect, and did not grow without fucose (Fig. 6). Collectively, these results demonstrate that SpAdK is essential for pneumococcal growth.

Fig. 6.

Arg-89 of SpAdK is essential for growth. S. pneumoniae adk complemented strains (S type-TTL02 and R type-TTL05) grew in the absence of fucose whereas the strains comprising adk-R89A point-mutation strains (S type-TTL03 and R type-TTL06) did not grow.

2.5. SpAdK increases intracellular ATP

Since AdK modulates ATP synthesis until ADP and ATP levels reach equilibrium, high concentration of fucose should produce high SpAdK activity, resulting in a higher level of ATP. Fucose was added into culture of the TTL01, and the intracellular ATP level was determined. At 1.0% fucose, the intracellular ATP level of the TTL01 strain was increased more than that of the D39 WT or TTL01 at 0.1% fucose, although the fucose itself did not affect the intracellular ATP level of the D39 WT (Fig. 7). These data consistently suggested that SpAdK is essential for ATP synthesis.

Fig. 7.

SpAdK increases intracellular ATP. Total ATP levels in D39 and TTL01 (fucose-inducible adk mutant strain) are shown.

2.6. Lack of functional SpAdK attenuates pneumococcal growth in vivo

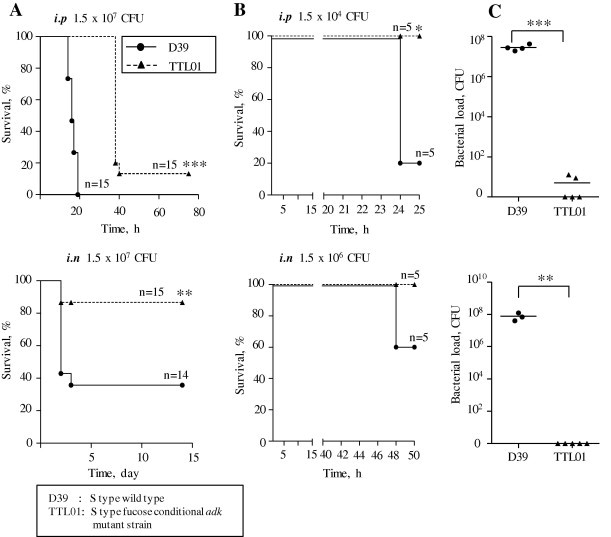

Since SpAdK plays an essential role in pneumococcal growth and ATP synthesis, role of SpAdK in virulence was determined in vivo. Prior to infection, the TTL01 strain was incubated in 0.5% fucose, and then administrated to mice via intranasal (i.n.) or intraperitoneal (i.p.) route (1.5 × 107 CFU per mice). Results showed that the mice infected with the TTL01 survived much longer than the mice infected with the D39 WT, in both i.p. and i.n. infections (Fig. 8A). In particular, no mice were survived after infection i.p. with D39 WT at 30 h post-infection whereas all the mice were survived after infection with the TTL01. Consistently, 5 mice survived at 14 days post-infection once 14 were infected i.n. with D39 WT initially (5/14) while 13 survied once 15 were infected i.n. with the TTL01 (13/15). Moreover, a lower infection dose was also performed: after 1.5 × 104 CFU per mice i.p. and 1.5 × 106 CFU per mice i.n. infections, survival percentage of the mice infected with the TTL01, particularly 4/5 (80%) (i.p.) and 2/5 (40%) (i.n.), was also significantly higher than that of the mice infected with the WT demonstrating that the TTL01 mutant was unable to survive in vivo (Fig. 8B). Moreover, the number of viable cells of the TTL01 infection recovered from mice blood was 107 and 108-fold lower, than those of the D39 WT respectively (Fig. 8C), after i.p. and i.n. infections, indicating that the viability of the TTL01 is dramatically decreased, compared to that of the D39 WT, in vivo.

Fig. 8.

(A) Attenuated virulence of the adk mutant in vivo. Groups of mice were infected i.p. or i.n. with approximately 1.5 × 107 CFU of D39 or TTL01 (n = 14–15), and survival time was monitored for 80 h or 14 days for i.p. and i.n. infections, respectively. (B) Attenuated virulence of the adk mutant in vivo in low infection-dose, groups of mice were infected i.p. or i.n. with approximately 1.5 × 104 CFU or 1.5 × 106 CFU of D39 or TTL01 (n = 5), and survival time was monitored for 24 h or 48 h for i.p. and i.n. infections, respectively. (C) Group of mice was infected i.p. with 1.5 × 104 or i.n. with 1.5 × 106 CFU of either D39 or TTL01 for 24 h (i.p.) or 48 h (i.n.), and number of viable bacteria in the blood was determined either 24 h (i.p.) or 48 h (i.n.) post infection after sacrifice, if they were alive, or post-mortem (n = 3–5).

3. Discussion

ATP is a pivotal metabolic intermediate required for cell growth. Although AdK is not an ATP synthase, it reversely catalyzes two molecules of ADP to AMP and ATP. Since inactivation of AdK in E. coli decreased the rate of macromolecular synthesis [20], AdK seems to control cell growth via cellular energy homeostasis. However, the role of AdK of Gram-positive bacteria in normal growth has not been characterized yet. In this study, we found that an isogenic adk deletion mutant of S. pneumoniae was not viable. Thus, a conditional mutant using fucose inducible adk promoter was constructed, and correlationship between fucose concentration and growth rate was demonstrated. Moreover, dependence of pneumococcal growth on SpAdK was corroborated using complementation test and mutational studies with R89A (Figs. 5 and 6). Consistently, the fucose-dependent adk strain (TTL01) showed reduced viability in vivo (Fig. 8).

Although there are more than 90 serotypes of pneumococci, BLAST search results showed that strains of various serotypes show highly conserved adk sequence. The adk gene of the D39 strain (type 2) shares 100% homology with the R6 strain as well as serotypes 1 (INV104 and P1031 strains), 6B (670-6B), 15B (Netherlands15B-37), A19 (TCH8431), 19A (Hungary19A-6), 19F (Taiwan19F-14), and 23F (ATCC 700669), and 99% homology with serotypes 3 (OXC141 strain), 4 (TIGR4), 14 (INV200) and 19F (CGSP14 and G54), showing that adk gene is highly conserved across the serotypes of S. pneumoniae. From these results, it is understood that so long as it has high sequence homology between serotypes or strains of S. pneumoniae, the adk gene can be a useful target for inactivating or modulating the SpAdK activity to develop chemotherapeutic agents. So far 6 human AdK homologs are known: cytoplasmic AdK1 (GenBank ID: 4502011) and AdK5 (GeneBank ID: 257051028), and mitochondrial AdK2 (GenBank ID: 14424799), AdK3 (GenBank ID: 6518533), AdK4 (GeneBank ID: 125157), and nuclear AdK6 (GeneBank ID: 4507351) [21]. Except human AdK6, SpAdK is homologous to human AdKs at primary sequence level: 29%, 39%, 37%, 35%, and 29% sequence identity for AdK1, AdK2, AdK3, AdK4, and AdK5, respectively. Although sequence identities of human AdK1–5 are not high, key catalytic residues and tertiary structure of human AdKs appear to be conserved as exemplified by human AdK2 (Fig. 2). Therefore, intervention of AdK activity for chemotherapeutics development should be based on allosteric modulation of SpAdK rather than direct interference with the active site.

AdK has been implicated in the pathogenesis in Gram-negative bacteria but not known in Gram-positive bacteria. For instance, AdK is secreted by the pathogenic Gram-negative strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia during infection and causes macrophage or mast cell death [7,22,23]. AdK secretion from pathogenic B. cepacia is specifically activated by eukaryotic protein α2-macroglobulin [22]. Pathogenic mucoid P. aeruginosa strains can increase the external ATP levels and kill macrophage via activation of P2Z receptor [23], which is responsible for pore formation on macrophage membrane [7,22,23]. Furthermore, at the site of inflammation, ATP concentration can be reached as high as hundreds micromolar [24], and ATP released by invading pathogens works as extracellular messengers and can be recognized readily by P2 receptors in innate immune cells. Although pneumococcal SpAdK was not secreted during infection (data not shown), our result does not rule out the possibility that pneumococcus would be lysed after invasion into the host cells resulting in release of SpAdK as well as nucleotides.

To adapt to hostile environments within the host, pathogenic bacteria can activate their virulence regulators via stringent signal responses mediated by guanosine 5′-diphosphate-3′-diphosphate (ppGpp) and guanosine 5′-triphosphate-3′-diphosphate ((p)ppGpp) [25]. The ppGpp mediates many physiological effects by direct or indirect control of transcription [25]. The ppGpp level in bacteria is modulated by both monofunctional synthetase RelA and bifunctional synthetase/hydrolase SpoT and RSH (RelA/SpoT homologue) proteins [25]. Both type of enzymes synthesize ppGpp from GDP or GTP, and by pyrophosphoryl transfer from ATP [26]. Most Gram-negative bacteria encode both RelA and SpoT whereas S. pneumoniae, a Gram-positive, encodes a bifunctional RSH protein RelSpn and a RelA-like synthetase homologue RelQ. In enterohemorrhagic E. coli, accumulation of ppGpp by RelA induction leads to the increased gene expression in the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) by activation of virulence regulatory genes [27]. In S. pneumoniae type 2 D39, RelSpn up-regulates the expression of pneumolysin (ply), a major pneumococcal virulence factor [28]. Since SpAdK regulates S. pneumoniae type 2 ATP level (Fig. 7) and ATP is pivotal for ppGpp metabolism, SpAdK might be involved in the pneumoccocal virulence. Therefore, further works on SpAdK virulence or cytotoxicity would warrant how SpAdK modulates cytotoxicity or virulence.

In this study, we investigated the structure and function of SpAdk, both in vitro and in vivo. We found SpAdK to be essential in pneumococcal growth. Cellular ATP levels increase in proportion to the SpAdK level, establishing that SpAdK is involved in energy homeostasis. The adk mutant showed defective growth in vitro and in vivo. Taken together, our results demonstrate that SpAdK is essential for pneumococcal growth.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Cloning and mutagenesis

Gene encoding AdK in S. pneumoniae D39 (accession number, NC_008533.1) was amplified and inserted into parallel His2 parallel vector [29] between BamHI and EcoRI restriction enzyme sites. All plasmids containing mutated sequences were generated using Quikchange II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies), and then confirmed by DNA sequencing. E. coli strains were cultured in Luria Broth (LB) medium. Extraction and purification of plasmid DNAs from E. coli were performed using Qiagen kit (Qiagen).

4.2. Protein purification and crystallization

All proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain and purified by affinity chromatography on Ni–NTA resin (Qiagen). His-tag was cleaved using tobacco etch virus protease [30] by dialysis against buffer A (25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 75 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 50 mM EDTA) overnight at 20 °C. The protein was further purified on Superdex-75 size exclusion column (GE HealthCare) equilibrated with buffer B (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2). Fractions containing pure AdK were pooled and concentrated by 10 kDa-centrifugal filters (Ambicom). Protein monodispersity was checked by dynamic light scattering measurement on DynaPro 100 (Protein Solutions) in the buffer B.

Crystallization of SpAdK and SpAdK:Ap5A was attempted at 22 °C, by the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method. SpAdK crystals were obtained by mixing 2.5 μl 18 mg/ml protein solution with 2.5 μl reservoir solution containing 2.0 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M CHES pH 9.5, 0.2 M Li2SO4, and 0.1 M CsCl2. SpAdk:Ap5A crystals appeared in the reservoir containing 0.1 M sodium acetate, 0.1 M sodium acetate pH 4.6, 30% PEG 8 K, and 50 mM NaF. The crystals were transferred to a cryoprotectant solution containing 22.0 and 27.5% glycerol for SpAdK and SpAdK:Ap5A, respectively.

4.3. Data collection and structure determination

Diffraction data was collected at Photon Factory beamline BL-5A (Japan), SPring-8 beamline BL26B1 (Japan), and Pohang Accelerator Laboratory beamlines 5C and 7A (Korea). Data processing and reduction were carried out using HKL2000 [31], iMoslfm [32] and POINTLESS [33] and MOLPROBITY [34]. Open, ligand-free SpAdK structure was solved by molecular replacement using PHENIX [35] with AdK from Marinibacillus marinus (PDB ID: 3FB4) and Burkholderia pseudomallei (PDB ID: 3GMT) as search models. Iterative manual model building and refinement were performed using COOT [36] and PHENIX [35]. The structure of SpAdK:Ap5A in closed conformation was solved by molecular replacement using open, ligand-free SpAdK structure as the search model. Statistics for data collection and structure refinement are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics.

| Conformation ligand | Closed Ap5A | Open |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection | ||

| Space group | P1 | P21 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 39.20, 48.34, 52.57 | 44.22, 53.7, 50.87 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 75.30, 72.95, 88.77 | 90, 114.46, 90 |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.48 (1.51–1.48)⁎ | 1.70 (1.73 – 1.70) |

| Rr.i.m.a | 0.070 (0.304) | 0.093 (0.104) |

| Rp.i.m.a | 0.049 (0.215) | 0.051 (0.054) |

| I/σI | 25.27 (5.97) | 7.97 (6.80) |

| Completeness (%) | 93.11 (87.46) | 97.84 (98.72) |

| Redundancy | 3.7 (3.4) | 3.5 (3.4) |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 50 – 1.48 | 25.05 – 1.69 |

| No. reflections | 54,770 | 23,924 |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.195/0.226 | 0.180/0.222 |

| No. atoms | 7,379 | 2,035 |

| Protein | 3,336 | 1,674 |

| Ligand/ion | 116 | 5 |

| Water | 583 | 356 |

| B-factors | 37.60 | 14.40 |

| Protein | 36.50 | 12.60 |

| Ligand/ion | ||

| Water | 46.00 | 22.80 |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 | 0.019 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.39 | 1.79 |

| Ramachandran plot | ||

| Most favored regions (%) | 95.1 | 95.2 |

| Additional allowed regions (%) | 4.9 | 4.8 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

Rr.i.m., redundancy-independent merging R factor; Rp.i.m., precision-indicating merging R factor [45].

4.4. Activity assay

Enzymatic activity of SpAdK was determined by monitoring either ATP or ADP production. ATP production assay was performed in buffer C (25 mM phosphate pH 7.2, 5 mM MgCl2, 65 mM KCl and 2 mM ADP). The buffer C was then preincubated at 37 °C for 5 min prior to the addition of SpAdK at the final concentration of 10 nM. The concentration of ATP was determined by following manufacturer’s instruction of ATP determination kit (Invitrogen). ADP production from ATP and AMP was measured as described previously [37]. Briefly, the reaction buffer D for measuring ADP production contained 25 mM phosphate pH 7.2, 5 mM MgCl2, 65 mM KCl, 0.12 mM NADH, 0.2 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, 10 units of both lactate dehydrogenase/pyruvate kinase mixture, 1.4 mM AMP and 50 μM ATP. ADP concentration was determined by subtracting the concentration of NADH consumed during the reaction from the NADH concentration of the control. All reagents for the assay were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich. Values shown are averaged ones from independent experiments in at least triplicate.

4.5. Bacterial strains conditions

The bacterial strains of S. pneumoniae and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table 2. Non-encapsulated S. pneumoniae CP1200, a derivative of Rx1 [38] or encapsulated S. pneumoniae D39 (serotype 2, NCTC7466) [39] was cultured in Casitone–tryptone-based medium (CAT) or Todd-Hewitt broth containing yeast extract (THY broth) as described previously [38,40]. Pneumococcal competence was controlled by appropriate addition of the competence stimulating peptide-1 as described previously [41]. Erythromycin (0.1 μg/ml) or tetracycline (1.0 μg/ml) was used to select pneumococcal transformants.

4.6. Construction of a fucose-inducible adk strain

A S. pneumoniae D39 fucose-inducible adk strain (D39 PfcsK-adk; TTL01) was constructed by replacing adk promoter with the PfcsK inducible promoter in the chromosome of S. pneumoniae using a triple joining PCR amplification with overlapping primers (Table 3). First, a cassette containing an erythromycin resistance marker (ermAM), a fucose promoter (PfcsK), and transcriptional terminators (t1,t2) that are located at the 5′ end of the PfcsK promoter was amplified from the Cheshire cassette, which was kindly provided by Morrison [42], using primers ermAM-F and ermAM-R [43]. Two arms were flanked by S. pneumoniae D39 DNA genome as follows: left arm contained a part of secY (upstream gene of adk) and ended at its stop codon, and was amplified by primers adk1 and adk2; right arm was initiated at adk start codon and forward 715 bp using primers adk3 and adk4. The cassette, left and right arms were used as templates for a triple-joining PCR using primers adk1 and adk4. The PCR product was integrated homogenously into S. pneumoniae D39 by transformation. The transformant was selected by 0.1 μg/ml erythromycin and 0.5% l-(−)-fucose (Sigma) and confirmed by sequencing.

Table 3.

Primers used in this study.

| Name | Sequence (5′ → 3′) |

|---|---|

| adk1 | tac ctt ggc tgg agc tca at |

| adk2 | tag gac tgc cta ccg aaa aat tat tct gtt ctg tcc atg a |

| adk3 | gga cga aga gag aag aaa aat gaa tct ttt gat tat ggg |

| adk4 | tcg att cga tcg ctc tag ac |

| ermAM-F | ttt ttc ggt agg cag tcc tac cgt ggc tta ccg ttc gta tag |

| ermAM-R | ttt tct tct ctc ttc gtc ctt ga |

| adk_HindIII | ccc aag ctt atg aat ctt ttg att atg ggc tta |

| adk_EcoRI | cga att ctt att tca aat ttg tca ata ctt ttt |

4.7. RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

S. pneumoniae D39 and TTL01 were cultured to exponential phase prior to isolation of the RNA by hot phenol method as described previously [43]. One microgram of bacterial RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using a random primer (Takara) and MLV-RT enzyme (SUPER Bio). Quantitative reverse transcriptional PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Intron). Each condition was analyzed in triplicate.

4.8. Complementation test

For complementation test, adk wild-type or R89A mutant containing their natural promoters were inserted into pET28a vector (Novagen), then subcloned into pMV158 vector [43] by using HindIII and EcoRI restriction enzymes. The transformation of pMV158::adk and pMV158::adk-R89A into S. pneumoniae D39 adk-inducible strains were performed as previously described. The transformants were selected by 0.1 μg/ml erythromycin and 1.0 μg/ml tetracycline, and followed by colony PCR screening using tetracycline resistance-specific primers for pMV158. Transformants were selected and then used for plasmid isolation. Recombinant’s nucleotide sequence was identified by PCR with adk_HindIII and adk_EcoRI primers and also confirmed by sequencing.

4.9. Pneumococcal ATP determination

S. pneumoniae was grown exponentially in THY with (0.1%, 0.5%, and 1.0%) or without fucose until A550 = 0.5. Bacterial pellet was lysed and used to determine ATP level as the instruction of ATP Determination Kit (Molecular Probes-Invitrogen). Quantitative determination of ATP in S. pneumoniae is based on recombinant firefly luciferase and l-luciferin reaction (luciferin + ATP + O2 → oxyluciferin + AMP + pyrophosphate + CO2 + light). Signals were detected via Luminometer (Tunner Biosystem) and ATP amount was quantified using an ATP standard curve.

4.10. Ethical statement for animal care and experiments

Male CD-1 (ICR) mice 4–5 weeks old (weighing approximately 20 g each, free-pathogens) were obtained from OrientBio Inc. (Seongnam, Korea), and acclimatized for a week. The animals were fed with water and sterile standard chow ad libitum. A specific pathogen-free barrier facility (12 h light/dark cycle, 22 ± 2 °C room temperature, 50 ± 10% relative humidity) at the School of Pharmacy at Sungkyunkwan University (Suwon, Korea) was used to maintain the animals. All animal experiments conformed to the animal care guidelines of the Korean Academy of Medical Sciences, and infection procedures followed protocol PH-530518-06 that was approved and monitored by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Sungkyunkwan University (Suwon, Korea). For colonization experiment, mice were anesthetized using ketamine solution (80–100 mg/kg) prior to sacrifice for only blood collection.

For in vivo virulence test, mice (n = 14–15) were infected either i.n. or i.p. with encapsulated D39 or its isogenic adk mutant TTL01 strain to evaluate effect of adk on pneumococcal survival and virulence. Prior to infection, pneumococci were cultured in THY broth in the presence of 0.5% or absence of fucose to approximately A550 = 0.3 (1.5 × 108 CFU/ml). Mouse was infected i.n. or i.p. with 1.5 × 107 CFU per mouse. The survival of mice was recorded within 80 h for i.p. infection or 14 days for i.n. infection. After infection, mice survival was monitored 8 times during first 4 days and 4 times until the end of the experiment.

To determine colonization of the bacteria, mice (n = 5) were infected with 1.5 × 104 CFU i.p. or 1.5 × 106 CFU i.n. Mice were anesthetized using ketamine solution prior to sacrifice either at 24 h post-infection for i.p. infection or 48 h post-infection for i.n. infection [44]. Viable cells number in the blood was counted after serial dilution with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) prior to plating onto THY blood agar for D39 or agar supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) fucose and 0.1 μg/ml of erythromycin for TTL01.

4.11. Antisera and Western blot

Group of 5-week-old male CD1 mice (n = 5) were immunized i.p. with 10 μg of purified SpAdK in combination with 100 μg of aluminum adjuvant (Sigma) at 14-day intervals. Mice were anesthetized using ketamine solution, and sera was collected from mice a week after the third immunization.

S. pneumoniae was grown exponentially in THY (A550 = 0.5) and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–Cl pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM protease inhibitor). Total proteins were collected and used for Western blot. Samples then were probed with appropriate antibody diluted 1:1000 fold in Tris buffer saline (TBS) containing 0.1% Tween20 (Sigma). The secondary antibody was anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G conjugated with horse radish peroxidase (HRP) diluted 1:10,000 fold with TBS containing 0.1% Tween20 (Sigma).

4.12. Statistical analyses

Most of the graphs and statistical analyses were prepared using SigmaPlot 11.0 software (Systat Software), except in vivo tests (Fig. 8), which were prepared using GraphPad Prism version 5.02. Statistical analysis was calculated using an appropriate One Way ANOVA (Duncan’s method, non-parametric), Student’s t-test (non-parametric), Mann Whitney U Test (non-parametric), or Log-rank Test. A value of P ⩽ 0.05 (denoted by ∗), P ⩽ 0.01 (denoted by ∗∗) and P ⩽ 0.001 (denoted by ∗∗∗), was considered significant. Data presented are the mean SD of the mean for 2–4 independent experiments.

Author contribution

Planned the experiments: DR SL. Performed the experiments: TT, TL. Analyzed the data: TT TL SL DR. Wrote the paper: TT TL SL DR.

Acknowledgements

We thank the beamline staff members at Photon Factory, SPring-8 and Pohang Accelerator Laboratory. We also acknowledge Dr. Donald Morrison for his donation of a Cheshire cassette and other vectors, for construction of the l-fucose-regulated strain. This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program, through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (NRF-2013R1A1A2059981 to S.L. and 2011-0024794 to D.R.), the Pioneer Research Center Program (2012-0009597) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), and the Woo Jang Chun Program (PJ009106) through the Rural Development Agency to S.L., and by the Korea Science & Engineering Foundation (WCU R33-10045) to D.R.

Contributor Information

Sangho Lee, Email: sangholee@skku.edu.

Dong-Kwon Rhee, Email: dkrhee@skku.edu.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

This document file contains Supplementary pdb1 file.

This document file contains Supplementary pdb2 file.

References

- 1.Liu L., Johnson H.L., Cousens S., Perin J., Scott S., Lawn J.E., Rudan I., Campbell H., Cibulskis R., Li M., Mathers C., Black R.E. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012;379:2151–2161. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell A.M., Mitchell T.J. Streptococcus pneumoniae: virulence factors and variation. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010;16:411–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee E.-J., Groisman E.A. Control of a Salmonella virulence locus by an ATP-sensing leader messenger RNA. Nature. 2012;486:271–275. doi: 10.1038/nature11090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkinson A. The energy charge of the adenylate pool as a regulatory parameter. Interaction with feedback modifiers. Biochemistry. 1968;7:4030–4034. doi: 10.1021/bi00851a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chapman A.G., Fall L., Atkinson D.E. Adenylate energy charge in Escherichia coli during growth and starvation. J. Bacteriol. 1971;108:1072–1086. doi: 10.1128/jb.108.3.1072-1086.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobs A., Didone L., Jobson J., Sofia M., Krysan D., Dunman P. Adenylate kinase release as a high-throughput-screening-compatible reporter of bacterial lysis for identification of antibacterial agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;51:26. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01640-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markaryan A., Zaborina O., Punj V., Chakrabarty A.M. Adenylate kinase as a virulence factor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:3345–3352. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.11.3345-3352.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dzeja P., Terzic A. Adenylate kinase and AMP signaling networks: metabolic monitoring, signal communication and body energy sensing. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009;10:1729–1772. doi: 10.3390/ijms10041729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haase G.H.W., Brune M., Reinstein J., Pai E.F., Pingoud A., Wittinghofer A. Adenylate kinases from thermosensitive Escherichia coli strains. J. Mol. Biol. 1989;207:151–162. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muller C.E., Schulz G.E. Structure of the complex between adenylate kinase from Escherichia coli and the inhibitor Ap5A refined at 1.9 A resolution. A model for a catalytic transition state. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;224:159–177. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90582-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henzler-Wildman K.A., Vu T., Lei M., Ott M., Wolf-Watz M., Fenn T., Pozharski E., Wilson M.A., Petsko G.A., Karplus M., Hübner C.G., Kern D. Intrinsic motions along an enzymatic reaction trajectory. Nature. 2007;450:838–844. doi: 10.1038/nature06410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holm L., ROsenstrom P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W545–W549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bae E., Phillips G.N. Structures and analysis of highly homologous psychrophilic, mesophilic, and thermophilic adenylate kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:28202–28208. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401865200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnamurthy H., Lou H., Kimple A., Vieille C., Cukier R.I. Associative mechanism for phosphoryl transfer: a molecular dynamics simulation of Escherichia coli adenylate kinase complexed with its substrates. Proteins. 2005;50:88–100. doi: 10.1002/prot.20301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellinzoni M., Haouz A., Graña M., Munier-Lehmann H., Shepard W., Alzari P. The crystal structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis adenylate kinase in complex with two molecules of ADP and Mg2+ supports an associative mechanism for phosphoryl transfer. Protein Sci. 2006;15:1489–1493. doi: 10.1110/ps.062163406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huss R.J., Glaser M. Identification and purification of an adenylate kinase-associated protein that influences the thermolability of adenylate kinase from a temperature-sensitive adk mutant of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:13370–13376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinstein J., Gilles A.-M., Rose T., Wittinghofer A., Girons I.S., Barzu O., Surewicz W.K., Mantsch H.H. Structural and catalytic role of Arginine 88 in Escherichia coli adenylate kinase as evidenced by chemical modification and site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:8107–8112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H.J., Nishikawa S., Tokutomi Y., Takenaka H., Hamada M., Kuby S.A., Uesugi S. In vitro mutagenesis studies at the arginine residues of adenylate kinase. A revised binding site for AMP in the X-ray-deduced model. Biochemistry. 1990;29:1107–1111. doi: 10.1021/bi00457a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bitoun J.P., Liao S., Yao X., Xie G.G., Wen Z.T. The Redox-sensing regulator Rex modulates central carbon metabolism, stress tolerance response and Biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chakrabarty A.M. Nucleoside diphosphate kinase: role in bacterial growth, virulence, cell signalling and polysaccharide synthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 1998;28:875–882. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drakou C.E., Malekkou A., Hayes J.M., Lederer C.W., Leonidas D.D., Oikonomakos N.G., Lamond A.I., Santama N., Zographos S.E. HCINAP is an atypical mammalian nuclear adenylate kinase with an ATPase motif: structural and functional studies. Proteins. 2012;80:206–220. doi: 10.1002/prot.23186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melnikov A., Zaborina O., Dhiman N., Prabhakar B.S., Chakrabarty A.M., Hendrickson W. Clinical and environmental isolates of Burkholderia cepacia exhibit differential cytotoxicity towards macrophages and mast cells. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;36:1481–1493. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaborina O., Misra N., Kostal J., Kamath S., Kapatral V., El-Idrissi M.E.-A., Prabhakar B.S., Chakrabarty A.M. P2Z-independent and P2Z receptor-mediated macrophage killing by Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from cystic fibrosis patients. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:5231–5242. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5231-5242.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber F.C., Esser P.R., Müller T., Ganesan J., Pellegatti P., Simon M.M., Zeiser R., Idzko M., Jakob T., Martin S.F. Lack of the purinergic receptor P2X7 results in resistance to contact hypersensitivity. J. Exp. Med. 2010;207:2609–2619. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dalebroux Z.D., Svensson S.L., Gaynor E.C., Swanson M.S. PpGpp conjures bacterial virulence. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010;74:171–199. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00046-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potrykus K., Cashel M. (p)ppGpp: still magical?∗. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;62:35–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakanishi N., Abe H., Ogura Y., Hayashi T., Tashiro K., Kuhara S., Sugimoto N., Tobe T. PpGpp with DksA controls gene expression in the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli through activation of two virulence regulatory genes. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:194–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kazmierczak K.M., Wayne K.J., Rechtsteiner A., Winkler M.E. Roles of relSpn in stringent response, global regulation and virulence of serotype 2 Streptococcus pneumoniae D39. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;72:590–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheffield P., Garrard S., Derewenda Z. Overcoming expression and purification problems of RhoGDI using a family of “parallel” expression vectors. Protein Expr. Purif. 1999;15:34–39. doi: 10.1006/prep.1998.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oldenburg P.J., Wyatt T.A., Factor P.H., Sisson J.H. Alcohol feeding blocks methacholine-induced airway responsiveness in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2008;296:L109–L114. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00487.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kareyeva A.V., Grivennikova V.G., Cecchini G., Vinogradov A.D. Molecular identification of the enzyme responsible for the mitochondrial NADH-supported ammonium-dependent hydrogen peroxide production. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:385–389. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Battye T.G., Kontogiannis L., Johnson O., Powell H.R., Leslie A.G. IMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen V.B., Arendall W.B., 3rd, Headd J.J., Keedy D.A., Immormino R.M., Kapral G.J., Murray L.W., Richardson J.S., Richardson D.C. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murshudov G.N., Vagin A.A., Dodson E.J. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emsley P., Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davlieva M., Shamoo Y. Structure and biochemical characterization of an adenylate kinase originating from the psychrophilic organism Marinibacillus marinus. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 2009;65:751–756. doi: 10.1107/S1744309109024348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi I.H., Shim J.H., Kim S.W., Kim S.N., Pyo S.N., Rhee D.K. Limited stress response in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microbiol. Immunol. 1999;43:807–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1999.tb02474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avery O.T., MacLeod C.M., McCarty M. Studies on the chemical nature of the substance inducing transformation of pneumococcal types induction of transformation by a desoxyribonucleic acid fraction isolated from pneumococcus type III. J. Exp. Med. 1944;79:137–158. doi: 10.1084/jem.79.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwon H.-Y., Kim S.-W., Choi M.-H., Ogunniyi A.D., Paton J.C., Park S.-H., Pyo S.-N., Rhee D.-K. Effect of heat shock and mutations in ClpL and ClpP on virulence gene expression in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:3757–3765. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.3757-3765.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bricker A.L., Camilli A. Transformation of a type 4 encapsulated strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999;172:131–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weng L., Biswas I., Morrison D.A. A self-deleting Cre–lox–ermAM cassette, Cheshire, for marker-less gene deletion in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2009;79:353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tran T.D.-H., Kwon H.-Y., Kim E.-H., Kim K.-W., Briles D.E., Pyo S., Rhee D.-K. Decrease in penicillin susceptibility due to heat shock protein ClpL in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:2714–2728. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01383-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stroeher U.H., Paton A.W., Ogunniyi A.D., Paton J.C. Mutation of luxS of Streptococcus pneumoniae affects virulence in a mouse model. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:3206–3212. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3206-3212.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weiss M.S. Global indicators of X-ray data quality. J. Appl. Cryst. 2001;34:130–135. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

This document file contains Supplementary pdb1 file.

This document file contains Supplementary pdb2 file.