Abstract

Stress is known to play an important role in alcohol abuse while binge drinking may increase individuals’ susceptibility to development of alcohol dependence. We set out to investigate whether binge drinkers (BD) compared to non-binge drinkers (NBD) are at a greater risk of increasing their desire for alcohol following experimental stress-induction (modified Trier Social Stress Test) (Experiment 1) and to explore the biological mechanisms underlying such an effect (Experiment 2). Pre-clinical evidence suggests that serotonin may mediate stress-induced reinstatement of alcohol intake. We therefore tested whether dietary tryptophan enhancement would modulate stress-induced desire for alcohol and whether it would affect the two populations (BD/NBD) differently. In Experiment 1 (14 NBD, 10 BD subjects; mean weekly alcohol intake 50.64 units) stress-induction selectively increased Strong Desire for alcohol (SD) compared to the non-stressful condition in BDs. Throughout the experiment, BDs reported greater Negative Reinforcement type of craving than NBDs but also a higher expectancy of alcohol-induced negative effects. In Experiment 2, forty-one subjects (22 NBD, 19 BD; mean alcohol intake 38.81 units) were given either the tryptophan-rich (TRP+; 9BD, 11NBD) or the control (CTR; 10BD, 11NBD) diet before undergoing stress-induction. In BDs, TRP+ diet prevented the stress-induced increase in SD that was observed in individuals receiving the CTR diet. In NBDs, TRP+ diet appeared to facilitate an increase in SD. These findings suggest that BDs may indeed be at a greater risk than NBDs of increasing their craving for alcohol when stressed. Furthermore, while enhancement of 5-HT function may moderate the impact of stress on craving in BDs, it seems to facilitate stress-induced craving in NBDs, suggesting that the serotonergic system may be differentially involved depending on individuals’ binge drinking status.

Keywords: stress, 5-HT, craving, binge drinking, alcoholism, tryptophan, incentive, human

Introduction

Stress is considered to be an important factor in the initiation, maintenance and relapse to alcohol abuse (Marlatt 1979; Brady and Sonne 1999; Lê and Shaham 2002; Breese et al. 2005). Human laboratory studies have supported a strong positive relationship between experimentally induced stress and alcohol-related behaviours. Stressors increase alcohol craving and subjective anxiety and induce autonomic changes (Sinha and O’Malley 1999; Coffey et al. 2002; Nesic and Duka 2006; Fox et al. 2007; Nesic and Duka 2008), and several studies have demonstrated an increase in alcohol consumption following acute stress in social drinkers (Higgins and Marlatt 1975; Pelham et al. 1997; De Wit et al. 2003; Nesic and Duka 2006) and alcoholics (Miller et al. 1974). However, the effects of stress on alcohol-related behaviours in humans are equivocal and appear to be moderated by several factors, including personality traits (Nesic and Duka 2008), gender (Nesic and Duka 2006; Chaplin et al. 2008) and drinking motives (Field and Powell 2007).

Binge drinking, a pattern of excessive alcohol consumption resulting in rapid increases in blood alcohol levels and drunkenness followed by days of abstinence (Townshend and Duka 2005), has been put forward as a factor that may facilitate the development of alcohol abuse (Duka et al. 2004; Stephens and Duka 2008). Very few studies, however, have examined the susceptibility of binge drinkers to stress although they appear to suggest that the binge drinking pattern may be related to greater susceptibility to stress-induced anxiety in rodents (Breese et al. 2005). Furthermore, preliminary studies conducted in our laboratory have demonstrated that heavy drinkers who ordinarily engage in binge drinking consume more alcohol during stress, compared to heavy drinkers who do not binge (Nesic and Duka 2005). This mirrors the pattern observed with binge and non-binge eaters, where stress increased the incentive value of snack foods in bingers and decreased it in non-bingers (Goldfield et al. 2008). Such experimental findings are indeed in line with an epidemiologic study by Dawson and colleagues (2005) which suggested that stress does not necessarily increase the frequency of drinking but rather the occurrence of heavy (binge) drinking episodes, as well as the observation that drinking to escape negative affect significantly predicts binge drinking (Williams and Clark 1998).

The mechanisms through which stress may modulate alcohol-related behaviours are not clear. It has been suggested that stress activates brain substrates of the incentive system (mesolimbic dopamine pathway and the extended amygdala), thus increasing individuals’ sensitivity to the positively reinforcing properties of drugs leading to increased motivation to use drugs (Piazza and Le Moal 1997; 1998). In support of this view, Field and Powell (2007) reported an increase in attentional bias for alcohol-related pictures (the index of incentive system activation) following stress in heavy social drinkers. However, although activation of the mesolimbic dopamine (DA) system is thought to underlie drug- and cue-induced priming (Stewart et al. 1984), there is evidence to suggest that other neurotransmitter systems may contribute to stress-induced priming (Stewart 2000; Lê and Shaham 2002; Liu and Weiss 2002; Stewart 2003). For instance, stress-induced reinstatement of alcohol-seeking in rats was blocked by the selective serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine, and not by naltrexone, a drug that is known to block opioid-induced activation of the mesolimbic DA system (Lê et al. 1999). Conversely, suppression of 5-HT release produced by intra-raphe infusion of 8-OH-DPAT [8-hydroxy-2-(di-n-propylamino)tetralin], a 5-HT1A agonist which reduces 5-HT release, was also found to increase sensitivity to reward (Fletcher et al. 1995), reinstate alcohol seeking in rats (Lê and Shaham 2002) and enhance response rates on tasks measuring response inhibition (Fletcher 1993). These findings taken together suggest that the effects of stress on alcohol-related behaviours may be associated with 5-HT–related disinhibition of alcohol-related behaviours (Lê and Shaham 2002).

A series of studies from our laboratory have demonstrated specific cognitive deficits in binge drinkers, including impaired inhibitory control (Townshend and Duka 2005; see Stephens and Duka 2008 for a review). Whether pre-existing or binge drinking-induced, such deficits may underlie bingers’ inability to control excessive drinking (Duka et al. 2004). Furthermore, a binge drinking pattern, like repeated detoxifications in alcoholic patients, appears to result in sensitisation of the amygdala, as demonstrated by the inappropriate generalization of learned fear in these populations (Stephens et al. 2005). We thus postulate that the pattern of drinking (i.e. binge vs. non-binge), independently of the total weekly alcohol intake, determines the sensitivity to the disinhibitory effects of stress on the incentive value of alcohol. This may lead bingers to experience higher craving for alcohol following stress induction.

The aim of the present experiments was to investigate the effects of stress on craving for alcohol in heavy social drinkers who commonly engage in binge drinking (bingers) and those whose alcohol consumption is more stable across the week (non-bingers). In addition, trait characteristics of the two groups of drinkers, including personality and anxiety traits as well as alcohol outcome expectancies were explored to further evaluate the distinctiveness of the two populations.

Experiment 1 set out to test the hypothesis that binge drinkers are more susceptible to stress-induced alcohol craving than those heavy drinkers who do not binge, and to examine their personality traits and motives for drinking. Experiment 2 aimed to replicate and extend these findings by using a larger sample and exploring the role of 5-HT in mediating the effects of stress on alcohol craving in bingers and non-bingers using a dietary tryptophan enhancement method (based on Markus et al. (2000a); see Nesic & Duka (2008) for detailed discussion of this approach).

According to Markus and colleagues (Markus et al. 1998; 1999; 2000a; 2000b; 2002), individuals who are stress-prone and who are thus thought to be likely to suffer from serotonergic deficit, are expected to benefit from tryptophan enhancement in stressful situations. Based on the results of Experiment 1, bingers appeared to be more sensitive to stress-induced anxiety and craving and were thus predicted to show improved stress resilience following tryptophan enhancement.

The lack of baseline craving measures in the two testing sessions was one of the main limitations of Experiment 1, therefore Experiment 2 implemented a pre-stress baseline craving measurements to enable a more sensitive analysis of craving fluctuations across the testing session.

Methods

Participants

Experiment 1

Thirty two heavy social drinkers (16 male, 16 female) aged 18–36 (mean = 22.13, SEM = 0.80) consuming on average 29.3–109.5 alcohol units per week (unit=8g of alcohol; mean = 47.94, SEM = 3.04) took part in this experiment. Participants were recruited via Experimental Psychology subject pool and were mostly students at the University of Sussex. Volunteers were only permitted to take part in this study if they were between 18 and 40 years of age and if they consumed 21 or more alcohol units per week (the maximum recommended weekly alcohol intake for men, Department of Health 1992), as reported in the Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ; Mehrabian and Russell 1978), which was included in the general recruitment questionnaire.

Participants were generally in good health, as verified by a medical interview, and their weights were within 15% of the normal weight limit for their heights. They were instructed to refrain from drinking alcohol for at least 12 h, smoking for at least 1 h, taking sleeping pills and other sedatives for 48 h and taking illicit drugs for at least 5 days before each testing session. Participants were told that a breathalyser test and urine drug tests might be administered during the experimental session to verify compliance. This is the standard procedure used in our lab to ensure compliance with abstinence requirements: participants, expecting a urine test, occasionally report at the beginning of the session if they had not been abstaining and their session is subsequently rescheduled. In addition, participants were asked not to eat anything and to avoid any strenuous physical activity for an hour before each session, in order to avoid post-prandial or activity-induced rise in cortisol secretion.

All subjects gave their informed consent before taking part in this study and the study was approved by University of Sussex Ethics Review Committee for the use of Human in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki for human subjects. Subjects received payment at the end of the experiment, as compensation for their time.

Experiment 2

A new sample of 67 subjects was recruited using the same criteria as in Experiment 1. Sixty seven heavy social drinkers aged 18–32 (mean = 21.04, SEM = 0.36) consuming on average 21.9–101.1 alcohol units per week (mean = 37.48, SE = 2.06) took part in this experiment. Participants were randomly assigned to receive the tryptophan-enriched (TRP+; 13 male, 20 female) or the control diet (CTR; 12 male, 22 female). All individuals who applied to take part in this experiment completed a detailed health questionnaire administered by a medical doctor and those with physical and psychiatric conditions that might be adversely affected by the experimental procedure or that might affect the outcome of the experiment were not permitted to take part. The rest of the recruitment procedure was the same as in Experiment 1 except that the participants were additionally asked to fast for 12 h prior to the testing session (see Experimental procedure).

Classification into bingers and non-bingers

Binge drinking scores were derived from the AUQ and the cut-off points for the two binge drinking groups represent the upper and the lower 33rd percentile of a sample of 425 heavy drinkers (>21 units per week) recruited by our laboratory who had previously completed the AUQ.

Experiment 1

Of the initial 32 participants who were tested in experiment 1, only 24 met the inclusion criteria for one of the two binge drinking groups, while the remaining 8 participants fell between the two cut-off points. Therefore only 14 non-bingers (NBD; 7 male, 7 female, binge drinking score ≤19) and 10 bingers (BD; 4 male, 6 female, binge drinking score ≥38) were included in the analyses presented here. The mean age of these 24 participants was 22.59 (SEM = 1.01) and they consumed on average 50.64 (SEM=3.88) alcohol units per week. Mean age and alcohol intake of the two binge drinking groups is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Age and drinking habits of bingers [B] and non-bingers [NB] in Experiments 1 and 2. In Experiment 2, participants were additionally divided into further two experimental groups, those receiving tryptophan-enriched [TRP+] and those receiving the control [CTR] diet.

| EXPERIMENT 1 | B (4 male, 6 female) |

NB (7 male, 7 female) |

|---|---|---|

|

Age (years) * |

18.0–25.0 (19.7 +/ −0.6) |

18.0–36.0 (24.6 +/− 1.4) |

|

Alcohol intake (units/week) |

32.9–109.5 (58.3 +/− 7.5) |

29.3–78.5 (45.2 +/− 3.5) |

|

Binge drinking score (derived from the AUQ) *** |

41.0–155.0 (79.6 +/− 13.6) |

6.5–18.7 (12.1 +/− 0.9) |

| EXPERIMENT 2 | B | NB | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| TRP+ (4 male, 5 female) |

CTR (3 male, 7 female) |

TRP+ (6 male, 5 female) |

CTR (4 male, 7 female) |

|

|

Age (years) |

18.0–31.0 (21.3 +/− 1.3) |

18.0–32.0 (21.5 +/− 1.2) |

18.0–30.0 (21.3 +/− 1.1) |

18.0–25.0 (20.7 +/− 0.7) |

|

Alcohol intake (units/week) * |

24.2–101.1 (53.1 +/− 10.5) |

25.0–62.9†† (43.5 +/− 3.9) |

23.1–48.3 (31.8 +/− 2.5) |

21.9–46.4 (30.0 +/− 2.6) |

|

Binge drinking score (derived from the AUQ) *** |

39.5–94.0 (64.2 +/− 6.1) |

38.0–92.3 (57.0 +/− 5.4) |

7.2–18.5 (13.0 +/− 0.9) |

6.9–19.0 (12.4 +/− 1.1) |

Values represent range (mean +/− SEM in brackets)

Mann Whitney U tests:

p<0.05,

p<0.001 – B vs. NB group,

p<0.01 – B vs. NB in the CTR group

Experiment 2

Of the initial 67 participants in Experiment 2, only 41 met the inclusion criteria for one of the two binge drinking groups; thus only 22 non-bingers (NBD; 6 male and 5 female from the TRP+ group, 4 male and 7 female from the CTR group; binge drinking score ≤19) and 19 bingers (BD; 4 male and 5 female from the TRP+ group and 3 male and 7 female from the CTR group; binge drinking score ≥38) were included in the analyses presented here. The mean age of these 41 participants was 21.20 (SEM = 0.52) and they consumed on average 38.81 (SEM=2.93) alcohol units per week (see Table 1 for mean age and alcohol intake of the two binge groups).

Experimental design

Experiment 1

Subjects were tested individually in a 2-way mixed design. The within-subjects factor was experimental condition, with fixed sequence of levels (day 1: non-stress; day 2: stress). Participants were subsequently divided into binge drinking [BD] and non-binge drinking [NBD] groups (between-subjects factor: binge group). Dependent variables were mood factors, cortisol and subjective craving. Experimental time point (pre-/post-stress) was an additional within-subjects factor for mood and cortisol measures.

Experiment 2

Participants were tested individually in a 3-way mixed design. They were randomly allocated either to tryptophan [TRP+] or the control [CTR] diet condition (between-subjects factor 1: diet; diets were administered in a double-blind manner). Participants were subsequently divided into binge drinking [BD] and non-binge drinking [NBD] groups (between-subjects factor 2: binge group). Experimental time point was introduced as a within-subjects factor for all dependent measures. The dependent variables were mood, craving for alcohol and salivary cortisol levels (two time points: pre-stress, post-stress) as well as heart rate (four time points: pre-stress baseline, instruction/speech preparation, speech delivery, mental arithmetic).

Stress induction

The stress induction procedure, based on the Trier Social Stress Test (Kirschbaum et al. 1993), has been modified and validated in our laboratory and found to induce negative mood and prevent a diurnal decrease in cortisol levels (Nesic and Duka 2006). The stressful condition consisted of preparation and delivery of a speech in front of the 8mm video camcorder and the experimenter, followed by mental arithmetic tasks. The matching non-stress condition consisted of browsing through an art history book, evaluating paintings from different art periods and completing a dot-to-dot booklet. The stress and non-stress condition were matched for duration, lasting approximately 23 minutes from start to finish (see our previous publications (Nesic and Duka 2006; 2008) for detailed description of both procedures).

Experiment 1

The order of the two procedures was fixed, with all participants undergoing the non-stress procedure on the first day of testing and the stress procedure on the second day. In our pilot study we found this sequence of conditions to result in a significant difference in post-manipulation cortisol levels between the two testing days, whereas no such difference was observed when non-stress condition was performed on the second day. It was considered likely that participants attending the second session 2–3 days after experiencing the stress induction could not relax during the non-stress procedure, perhaps anticipating another stressful experience.

Experiment 2

All participants were subjected only to the stressful condition.

Dietary manipulation (Nesic and Duka 2008)

This dietary tryptophan manipulation (high carbohydrate meal with the addition of either the tryptophan-rich amino acid α-lactalbumin or the tryptophan-poor amino acid casein) was based on the procedure developed by Markus and colleagues (2000a), who reported a significant increase in the ratio of tryptophan to other long neutral amino acids (LNAA) and selective increase in plasma prolactin concentration in high stress-prone subjects approximately 90 minutes after the end of this dietary manipulation. The original procedure was modified and tested in our laboratory and found to be effective in increasing the ratio of tryptophan to other long neutral amino acids (LNAA) (Nesic et al. 2003). Compared to baseline, tryptophan-rich [TRP+] diet produced an increase in the serum tryptophan/LNAA ratio by an average of 29.01%, while the control [CTR] diet tended to reduce the ratio by 15.29% as measured approximately 85 minutes after lunch (Nesic et al. 2003). This dietary manipulation additionally produced physiological and behavioural effects for up to 130 minutes after the end of lunch (Nesic et al. 2003; Nesic and Duka 2008). For a detailed description of the dietary procedure, see Nesic and Duka (2008).

Physiological measurements

Salivary cortisol

Saliva samples were collected using Salivettes (Sarstedt). Participants were instructed to place the cotton swab in their mouth and chew on it gently for 2 min. The participants then replaced the swab into the Salivette, which was sealed and stored in a freezer at −20°C until analysis using DELFIA assays (Wood et al. 1997). Saliva samples were taken twice on each testing day, at baseline and then approximately 30 minutes later (8–9 minutes after the end of the stress manipulation), which corresponds to the time when salivary cortisol levels were found to peak (10 minutes after the stress procedure; Kirschbaum et al. 1993).

Blood alcohol level (BAL)

BAL was derived from the breath alcohol level measurements using the Lion Alcolmeter at the beginning of each testing session to ensure compliance with the abstinence requirement of the study. Individuals whose BAL was above 0% were not allowed to participate in the study.

Heart rate. (Experiment 2 only)

Heart rate was measured using Polar S610 heart rate monitor. The measurements were taken continuously at 5-second intervals throughout the stress-inducing procedure (between the time points t2 and t3). For the purposes of statistical analyses, mean heart rate was calculated for the 30-second baseline period as well as for each of the three stages of the stressful procedure (preparation, speech, mental arithmetics).

Subjective measurements

The Alcohol Use Questionnaire (AUQ)

The AUQ (Mehrabian and Russell 1978) is a self-report questionnaire that establishes the average weekly alcohol intake over a 6-month period and with information about patterns of drinking. A “binge drinking” score was calculated for all participants on the basis of the information given in items 10, 11, and 12 of the AUQ [Speed of drinking (average drinks per hour); number of times being drunk in the previous 6 months; percentage of times getting drunk when drinking (average); see Mehrabian and Russell 1978 for details on scoring]. This score gives an insight into the drinking patterns of the participants rather than just a measure of alcohol intake. Participants who have a high “binge score” and drink frequently but irregularly may have a similar intake of alcohol to those with a lower “binge score” who drink on a regular basis.

Mood Questionnaires

The Profile of Mood States (POMS; McNair et al. 1971) is a list of 72 mood-related adjectives, which are rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from “not at all” [0] to “extremely” [4]. These items are grouped into 8 basic factors (Anxiety, Depression, Anger, Vigour, Fatigue, Confusion, Friendliness and Elation) as well as two composite scores, Arousal [(Anxiety + Vigour) − (Fatigue + Confusion)] and Positive Mood (Elation − Depression). The KUSTA (KUSTA: Wendt et al. 1985; Binz and Wendt 1990) consists of three 17-point bipolar scales (Mood, Activity, Tension/Relaxation) and three 17-point scales ranging from ‘not at all’ [1] to ‘extremely strong’ [17] (Happiness, Anxiety and Anger). For the purposes of this paper only Anxiety, Depression, Anger and the two composite scores (Arousal and Positive Mood) from POMS as well as the Tension/Relaxation scores from KUSTA were analysed, as our previous research identified these factors as the most sensitive indicators of the stress induction procedure.

Desire for Alcohol Questionnaire (DAQ)

The DAQ (Love et al. 1998) is a 14-item questionnaire that measures four different aspects of craving for alcohol: Mild Desire, Strong Desire with Intention to Drink, Negative Reinforcement and Loss of Control over alcohol use. The participants were required to rate how much each statement applied to them at that particular moment by writing a mark on a Likert-type 7-point scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ [1] to ‘strongly agree’ [7].

Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI)

The TCI (Cloninger et al. 1994) is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 240 statements, each rated on a 2-point scale (‘True’ vs. ‘False’). The questionnaire assesses four dimensions of temperament [Harm Avoidance (HA), Novelty Seeking (NS), Reward Dependence (RD) and Persistence (P)] and three dimensions of character [Self-directedness (SD), Co-operativeness (C) and Self-transcendence (ST)].

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI – trait version)

The STAI (Spielberger et al. 1990) is a 20-item questionnaire that measures the construct of general anxiety. Participants indicated on a scale of 1 to 4 whether each statement describes what they generally feel (1=almost never, 4=almost always).

Alcohol Expectancy Questionnair (AEQ)

The AEQ (based on Fromme et al. 1993) is a 38-item questionnaire that assesses the expectation of both positive and negative effects of alcohol. Subjects were required to rate each statement on a scale from 1 (‘Disagree’) to 4 (‘Agree’). The questionnaire items are grouped into four positive factors (Enhanced Sociability, Tension Reduction, ‘Liquid Courage’, Enhanced Sexuality) and three negative factors (Cognitive and Behavioural Impairments, Increased Risk-taking and Aggression, Self-perception).

Experimental procedure

Experiment 1

AUQ and STAI questionnaires were completed during the recruitment process. Participants were tested individually on two non-consecutive days within the same week. The testing sessions were conducted either in the morning (starting at 10.30 or 11.50h) or in the afternoon (13.10 or 14.30h) and each subject began both testing sessions at exactly the same time in order to control for the effects of the diurnal variation in cortisol secretion.

Upon their arrival to the Human Psychopharmacology laboratory for each testing session, participants were seated in the waiting room where they were given the information sheet and asked to complete AUQ again (session 1) or AEQ (session 2). After signing the consent form, subjects’ BAL was tested and they were taken into the experimental cubicle where they completed POMS and KUSTA questionnaires and provided the first saliva sample [time point: pre-stress]. After this, participants were subjected to either the non-stress procedure (session 1) or the stressful procedure (session 2). Immediately after the end of the procedure participants again completed POMS and KUSTA questionnaires and, approximately 8 minutes after the end of the experimental procedure, provided another sample of saliva and completed the DAQ [time point: post-stress]. Following this, participants completed a battery of cognitive tests (not reported) and were allowed to leave the laboratory. At the end of the first testing session, participants were given the TCI to complete at home and return to the laboratory when they arrived for the second testing session. At the end of the second testing session, participants were debriefed about the purposes of the study and paid for participation.

Experiment 2

Several days before the testing sessions participants underwent the medical assessment and were given the battery of trait questionnaires (AUQ, STAI and AEQ) to complete at home and hand in to the experimenter at the start of the testing session.

Participants were instructed to fast for at least 12 h before the main experimental session (only permitted water and tea without sugar and milk) and were told that compliance would be tested using saliva samples. While compliance with fasting instructions was not verified in this study, results from our pilot study using this type of instruction revealed that volunteers generally tended to be compliant, as indicated by blood glucose levels at the beginning of the session (mean +/− SEM: 95.13 +/− 1.89 mg/dl).

On the day of testing, participants arrived to the laboratory in the morning. After the breathalyser test they were seated in the waiting room for about 10 minutes before being taken to the main experimental cubicle where they completed POMS, DAQ and KUSTA questionnaires and gave a saliva sample (data from this measurement point are not reported here). Participants were then instructed to return to the waiting room so that the dietary manipulation could start. Each participant was given a 500ml bottle of water after breakfast to consume freely throughout the testing session and smokers were allowed to smoke immediately after breakfast, snack and lunch (if they wished to do so). Following breakfast, participants were asked to complete the TCI and were then allowed to read magazines or books during the periods of waiting between meals. After the end of the dietary manipulation, participants were allowed to rest for approximately one hour, after which they were asked to put on the heart rate monitoring equipment. Fifteen minutes later participants were taken to the main experimental cubicle where they completed POMS, DAQ and KUSTA questionnaires and provided another saliva sample [time point: pre-stress]. The stress-induction started one 85 minutes after the end of the dietary manipulation and lasted approximately 23 minutes, after which participants again completed POMS, DAQ and KUSTA and gave a sample of saliva [time point: post-stress]. Participants then performed a series of other tests (not reported here), after which they were debriefed about the purpose of the study, paid for their participation and allowed to leave the laboratory.

Statistical analyses

Experiment 1

Gender distribution across the two binge groups was evaluated using chi-square test. Due to significant skewness of the data (Kolmogorov-Smirnov ps<0.01), differences in demographic characteristics between the two binge groups were analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Trait differences between the two groups were analysed by univariate ANOVAs with binge group as a between-subjects factor.

Repeated-measures ANOVAs were used for salivary cortisol levels and for mood variables, as measured by POMS and KUSTA, with experimental condition (stress induction: non-stress vs. stress condition) and time point (pre- vs. post-stress induction) being the within-subjects factors and the binge group (BD vs. NBD) as a between-subjects factor. DAQ data were analysed with a repeated-measures ANOVAs, with binge group as a between-subjects factor and the experimental condition as the within-subjects factor.

Significant interactions were explored with appropriate post-hoc t-tests.

All analyses were performed using SPSS 20 software.

Experiment 2

The distribution of gender and time of testing (early vs. late slot) across the four groups were evaluated using the chi-square tests. Due to significant skewness of the data (Kolmogorov-Smirnov ps<0.001), differences in demographic characteristics between the four experimental groups (binge × diet) were analysed with Kruskal-Wallis test and, where appropriate, post-hoc Mann-Whitney U tests. Trait differences between the two participant groups were analysed by univariate ANOVAs with binge group as a between-subjects factor.

Cortisol, mood and craving data were analysed using three-way mixed ANOVAs, with diet group (TRP+ vs. CTR) and binge group (BD vs. NBD) as between-subject factors and time point (Pre-stress vs. Post-stress) as a within-subjects factor. Average heart rate was analysed using a three-way mixed ANOVA with phase of the stress manipulation (pre-stress baseline vs. instruction/preparation vs. speech vs. mental arithmetics) as a within-subject factor and diet and binge groups as between-subjects factors.

Significant interactions were explored with appropriate post-hoc t-tests and contrasts.

All analyses were performed using SPSS 20 software.

Results

Population characteristics

Experiment 1

Gender distribution was not significantly different across the two binge groups (χ2[1]=0.24, NS). The two binge groups were matched with respect to their habitual alcohol intake level (units per week; Mann-Whitney U=101.0, p>0.07) but not age, as bingers were significantly younger than non-bingers (Mann-Whitney U=31.5, p<0.05). No significant differences between the groups were observed with respect to illicit drug use (data not shown). Demographic characteristics of BD and NBD individuals are presented in Table 1.

A significant main effect of binge group was observed for TCI Self-Directedness (F[1,21]=9.14, p<0.01). In the AEQ, bingers reported significantly greater expectancy of alcohol-induced Cognitive & Behavioural Impairment (F[1,22]=5.78, p<0.05) and Risk & Aggression (F[1,22]=9.11, p<0.01. STAI, TCI and alcohol expectancy scores are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Trait questionnaire and alcohol expectancy scores of bingers [B] and non-bingers [NB] in Experiments 1 and 2.

| EXPERIMENT 1 | EXPERIMENT 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (4 male, 6 female) |

NB (7 male, 7 female) |

B (7 male, 12 female) |

NB (10 male,12 female) |

|

|

STAI Trait Anxiety |

52.2 (3.6) | 42.5 (3.0) | 41.2 (2.4) | 38.2 (1.7) |

|

TCI Novelty Seeking |

25.6 (2.1) | 22.9 (1.7) | 25.5 (1.3) | 24.6 (1.6) |

|

TCI Harm Avoidance |

19.2 (2.6) | 14.7 (2.0) | 17.5 (1.3) | 14.2 (1.4) |

|

TCI Reward Dependence |

16.6 (0.5) | 14.9 (1.3) | 16.3 (0.9) | 17.0 (0.7) |

|

TCI Persistence |

4.2 (0.6) | 4.6 (0.7) | 3.0 (0.5) | 4.9 (0.5)*# |

|

TCI Self-Directedness |

17.4 (2.4) | 27.8 (2.6)** | 25.3 (1.6) | 30.6 (1.4)*# |

|

TCI Co-operativeness |

30.4 (1.8) | 33.3 (1.6) | 33.5 (1.4) | 33.7 (1.2) |

|

TCI Self-Transcendence |

13.2 (2.4) | 15.9 (1.7) | 10.6 (1.4) | 12.1 (1.2) |

|

AEQ Sociability |

27.7 (0.8) | 25.0 (0.9)* | 27.0 (0.9) | 26.7 (0.7) |

|

AEQ Tension Reduction |

7.5 (0.5) | 8.1 (0.6) | 7.2 (0.4) | 7.7 (0.4) |

|

AEQ ‘Liquid Courage’ |

13.8 (0.6) | 11.9 (0.8) | 13.8 (0.5) | 12.7 (0.4) |

|

AEQ Sexuality |

10.5 (1.1) | 8.8 (0.7) | 9.3 (0.7) | 9.5 (0.5) |

|

AEQ Cognitive & Behavioural Impairment |

25.7 (1.4) | 21.6 (1.0)* | 25.8 (1.1) | 23.3 (0.8) |

|

AEQ Risk & Aggression |

14.5 (1.0) | 10.4 (0.9)** | 13.6 (0.6) | 11.6 (0.6)* |

|

AEQ Self-Perception |

7.6 (0.7) | 7.4 (0.7) | 7.9 (0.6) | 6.7 (0.5) |

Values represent means (SEM in brackets).

p<0.05,

p<0.01 – ANOVA main effect of binge group;

– the main effect did not remain significant when controlling for the habitual alcohol intake level (ANCOVA)

Although the difference in habitual weekly alcohol intake between the two groups of drinkers only approached significance, all subsequent ANOVAs were repeated including this variable as a covariate, in order to control for any confounding influences. However, since the inclusion of the covariate did not affect the significance of the main findings, only the results of original ANOVAs are reported here.

Experiment 2

Demographic characteristics of BD and NBD individuals allocated to the two diet conditions are presented in Table 1. The four experimental groups were matched for gender and time of testing (χ2[3]<1.47, NS) as well as for age (Kruskal-Wallis p>0.10) and illicit drug use (data not shown). However, a significant group difference with respect to the habitual level of alcohol use was observed (Kruskal-Wallis χ2[3]=8.97, p<0.05) reflecting significantly greater weekly alcohol consumption level in bingers compared to non-bingers (Mann-Whitney U=319.50, p<0.005), particularly in the CTR diet group (Mann-Whitney U=91.50, p<0.01).

In view of the significant group differences in habitual alcohol intake, and in order to differentiate between the effects of exposure to high levels of alcohol and the specific effects of drinking pattern (i.e. binge drinking), all ANOVAs of trait measures and the experimental outcome measures were thus repeated with the inclusion of this variable as a covariate. The results of the ANCOVAs are reported only when they differ from the findings of the original ANOVAs.

Analyses of TCI scores revealed that bingers were characterized by less Persistence and Self-Directedness than non-bingers (main effect of binge group; Fs[1,39]>6.33, ps<0.05; Table 2). However, both effects appeared to be at least partly related to the differential level of alcohol intake (ANCOVAs: p=0.07 and p=0.09, respectively). Also, compared to non-bingers, bingers gave higher ratings of AEQ factor Risk & Aggression (main effect of binge group: F[1,39]=6.20, p<0.05; Table 2) and this effect remained significant in the subsequent ANCOVA (p<0.05).

Salivary cortisol levels

Experiment 1

ANOVA revealed a significant interaction of experimental condition and time point (F[1,22]=6.29, p<0.05), reflecting a significant decline in cortisol levels during the non-stressful session (Pre-NS: mean 9.2+/−SEM 1.2 nMol/l, Post-NS: mean 6.0+/−SEM 0.9 nMol/l; t[31]=6.62, p<0.001) and no change during the stressful session (Pre-S: mean 10.3+/−SEM 1.1 nMol/l, Post-S: mean 10.6+/−SEM 1.0 nMol/l; p>0.70). Consequently, cortisol levels were significantly higher at the end of the stressful procedure compared to the end of the non-stressful procedure (t[31]=4.68, p<0.001). No other significant main effects or interactions were revealed in the analysis of cortisol levels.

Experiment 2

A significant main effect of time point reflected stress-induced increase in cortisol levels in the majority of participants (Pre-Stress: mean 8.4+/−SEM 0.5 nMol/l, Post-Stress: mean 11.9+/−SEM 0.9 nMol/l; F[1,37]=22.23, p<0.001). No other main effects or interactions were observed in this analysis.

Heart rate

ANOVA of average heart rates at 4 phases of the stress manipulation revealed a significant effect of time (Huynh-Feldt F[2.15,53.76]=14.61, p<0.001), indicating an increase of heart rate during speech delivery (simple contrast comparison to baseline: F[1,25]=17.62, p<0.001).

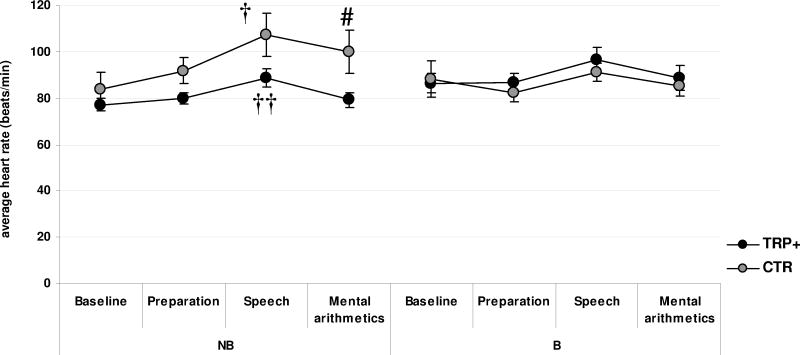

A significant interaction of time point, diet and binge group (Huynh-Feldt F[2.15,53.76]=4.61, p<0.05; Fig. 1) demonstrated that diet modulated heart rate changes during the stress procedure only in non-bingers (time × diet interaction within NBD group: Huynh-Feldt F[2.07,31.07]=3.53, p<0.05). Non-bingers showed a significant increase in heart rate during stress (main effect of time point: Huynh-Feldt F[2.07,24.55]=17.49, p<0.001) although those receiving TRP+ diet were characterized by lower increase during mental arithmetic compared to those receiving the CTR diet (simple contrast vs. baseline within NBD group: F[1,15]=5.59, p<0.05). On the other hand, bingers did not show a significant increase in heart rate during any stage of the stressful procedure and their heart rate was not modulated by diet (Fs[3,30]<2.63, ps>0.06).

Figure 1.

Heart Rate (mean, SEM) at different stages during the stressful procedure in bingers [B] and non-bingers [NB) following tryptophan-rich (TRP+) and control (CTR) dietary manipulation in Experiment 3. # p<0.05 – simple contrast vs. baseline (interaction of diet and binge group); † p<0.05, †† p<0.01 – paired t-test vs. baseline

Subsequent ANCOVA revealed an even more robust time × diet × binge group interaction (Huynh-Feldt F[1.78,46.31]=5.65, p<0.01), suggesting that the differential effects of diet and stress in the two groups of drinkers were not related to the differences in their overall weekly alcohol intake.

Mood

Experiment 1

Analysis of ood variables revealed that the stressful manipulation was effective in modulating Anxiety, Anger and Tension/Relaxation (time point × condition interactions: Fs[1,22]>11.08, p<0.005). In the stressful condition, participants reported a significant increase in the subjective feelings of anxiety and tension (paired ts[31]> 4.27, ps<0.001) while no significant change was observed in the non-stressful condition (ps>0.09). Participants also reported a significant increase in anger following the stressful procedure (t[31]=2.74, p<0.05) while a reduction in anger was observed in the non-stress condition (t[31]=2.46, p<0.05). Consequently, the levels of anxiety, tension and anger were significantly higher at the end of the stressful, compared to the end of the non-stressful session (paired ts[31]>3.49, ps<0.01). The stress manipulation did not affect depression scores, although a main effect of binge group was observed for this measure (F[1,22]=8.59, p<0.01), reflecting higher scores overall in binge drinkers compared to their non-bingeing counterparts.

A three-way interaction of experimental condition, time point and binge group was observed for anxiety scores (F[1,22]=5.46, p<0.05; Table 3). Although both groups of drinkers reported significantly higher anxiety levels at the end of the stressful compared to the end of the non-stressful procedure (t[9]=4.36, p<0.005 and t[13]=2.64, p<0.05 respectively for bingers and non-bingers), only binge drinkers reported a significant increase in anxiety levels following stress induction (paired t-test vs. baseline in the stressful condition; BDs: t[9]=3.44, p<0.01, NBDs: t[13]=2.04, p>0.06).

Table 3.

Mood ratings of bingers [B] and non-bingers [NB] during the non-stress [NS] and the stressful [S] testing session in Experiment 1

| Non-stress [NS] | Stress [S] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Pre- | Post- | Pre- | Post- | ||

|

POMS Anxiety |

B | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.2)** | 0.3 (0.2)** | 1.3 (0.3) |

| NB | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1)* | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.2) | |

|

POMS Depression |

B# | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.7 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) |

| NB | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | |

|

POMS Anger§§ |

B | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.3) |

| NB | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | 0.5 (0.1) | |

|

POMS Arousal |

B | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.5) | −0.4 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.5) |

| NB | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.3) | |

|

POMS Positive Mood |

B | 0.7 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.4 (0.4) |

| NB | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.3 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.3) | |

|

KUSTA Tension/Relaxationत |

B | 10.3 (1.2) | 10.6 (1.3) | 9.7 (1.3) | 6.4 (1.4) |

| NB | 12.2 (1.1) | 12.9 (0.9) | 11.4 (1.2) | 9.8 (0.9) | |

The measurements were taken at baseline [Pre-] and immediately after the stress manipulation [Post-]. Values represent means (+/−SEM).

- reverse rating: low score=tense, high score=relaxed).

P<0.005 significant effects of stress (ANOVA condition × time point interaction)

p<0.05 main effect of binge group

p<0.05,

p<0.01 – post-hoc paired t-tests vs. Post-Stress measurements within binger and non-binger group (ANOVA condition × time point × binge group interaction)

No other significant main effects of interactions with binge group were observed. Mood scores at the beginning and end of each experimental session in bingers and non-bingers are presented in Table 3.

Experiment 2

Stress decreased Positive Mood and increased Anxiety, Depression, Anger and Tension in the majority of participants (main effect of time point; Fs[1,37]>5.72, ps<0.05) and neither diet nor binge group modulated the effects of stress on any of the mood measurements (interactions with time point n.s.).

Diet, however, did have differential effects on Tension/Relaxation scores in the two binge groups irrespective of the stressful manipulation (binge group × diet interaction: F[1,36]=4.51, p<0.05). Whilst non-bingers in the CTR dietary condition reported, on average, more tension than bingers (NBD: mean 7.77+/−SEM 1.04, BD: mean 11.05+/−SEM 0.82; 1=maximum tense, 17=maximum relaxed; t[19]=2.44, p<0.05), this difference was abolished in the TRP+ condition (NBD: mean 10.70+/−SEM 1.05, BD: mean 9.72+/−SEM 1.06; NS) because the TRP+ diet tended to selectively reduce tension in non-bingers only (comparison to CTR: t[19]=1.98, p=0.062). Inclusion of habitual alcohol intake level as a covariate did not alter the significance of this interaction.

In addition to this, independently of the dietary manipulation, bingers, compared to non-bingers, reported less Positive Mood and lower Arousal throughout the testing session (main effects of binge group: Fs[1,37]>5.07, ps<0.05). While the difference in Arousal between the two binge group appeared to be at least partly due to their different level of alcohol intake (ANCOVA p=0.10), the difference in Positive Mood appeared to be independent of this covariate (ANCOVA main effect of binge group: F[1,36]=5.51, p<0.05)

Means and standard errors for each of the four experimental groups at pre-stress and post-stress time points are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Mood ratings of bingers [B] and non-bingers [NB] before [Pre-] and immediately after stress induction [Post-] in Experiment 2 (there was no non-stress condition).

| Pre- | Post- | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

POMS Anxiety§§§ |

B | 0.2 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.2) |

| NB | 0.4 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.2) | |

|

POMS Depression |

B | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.2) |

| NB | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.1) | |

|

POMS Anger§§ |

B | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.6 (0.2) |

| NB | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.1) | |

|

POMS Arousal |

B*# | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.2 (0.3) |

| NB | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.5 (0.4) | |

|

POMS Positive Mood§§ |

B** | 1.1 (0.1) | 0.2 (0.2) |

| NB | 1.4 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.2) | |

|

KUSTA Tension/Relaxation‡§§§ |

B | 12.4 (0.7) | 8.5 (0.9) |

| NB | 10.9 (0.9) | 7.4 (0.9) |

Values represent means (+/−SEM).

- reverse rating: low score=tense, high score=relaxed).

p<0.01,

p<0.001 – significant effects of stress (ANOVA main effect of time point)

p<0.05

p<0.01 – ANOVA main effect of binge group.

– the main effect did not remain significant when controlling for the habitual alcohol intake level (ANCOVA)

Craving for alcohol

Experiment 1

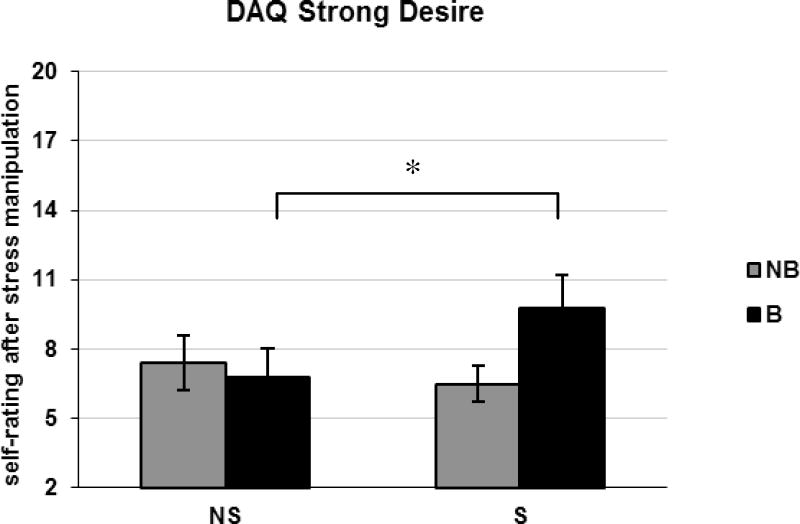

Analysis of the DAQ factors revealed two significant effects. A significant main effect of binge group was observed for the Negative Reinforcement factor (F[1,22]=7.34, p<0.05), indicating that bingers reported significantly higher negative reinforcement motivated craving in both testing sessions (means+/−SEM across the two testing sessions: BD=13.2+/−1.3, NBD=9.2+/−0.9).

A differential effect of stressful manipulation in bingers and non-bingers was apparent for the Strong Desire with Intention to Drink (interaction of binge group and experimental condition: F[1,22]=5.66, p<0.05; Fig. 2). Post-hoc tests indicated that only participants in the binge group reported increased craving following stress induction (t[9]=−2.60, p<0.05) while non-bingers did not (p>0.40). The increase in Strong Desire displayed by binge drinkers was significantly different from zero (mean change = 2.85 +/− 1.14 points; one sample t[9]=2.60, p<0.05).

Figure 2.

DAQ Strong Desire with Intention to Drink factor scores (means, SEM) in bingers [B] and non-bingers [NB] in Experiment 1. Measurements were taken at the end of the non-stressful [NS] and the stressful [S] procedure; *p<0.05 (independent t-test: S vs. NS condition).

The average Mild Desire, Negative Reinforcement and Loss of Control factor scores for the two binge groups are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Desire for Alcohol Questionnaire (DAQ) ratings of bingers [B] and non-bingers [NB] during the non-stress [NS] and the stressful [S] testing session in Experiments 1.

| Non-Stress [NS] |

Stress [S] |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

DAQ Mild Desire |

B | 19.2 (2.0) | 22.8 (1.6) |

| NB | 18.1 (1.9) | 18.8 (1.5) | |

|

DAQ Negative Reinforcement |

B# | 12.2 (1.4) | 14.3 (1.3) |

| NB | 8.9 (1.0) | 9.5 (1.1) | |

|

DAQ Loss of Control |

B | 5.0 (0.6) | 6.0 (1.2) |

| NB | 4.8 (0.8) | 3.9 (0.7) |

The measurements were taken immediately after the stress/non-stress procedure Values represent means (+/−SEM).

p<0.05 (ANOVA main effect of binge group)

Experiment 2

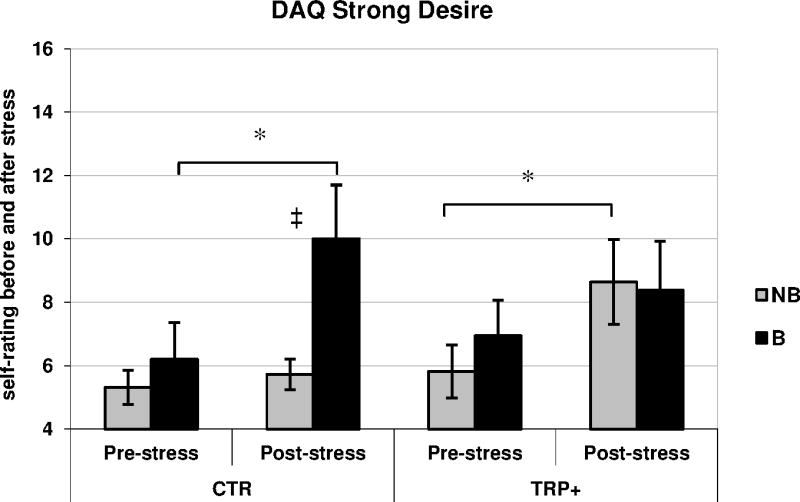

In the CTR dietary condition bingers displayed a significant increase in the DAQ ‘Strong Desire with Intentions to Drink’ scores, which was not observed in the TRP+ condition (ANOVA 3-way interaction: F[1,37]=6.99, p<0.05; CTR condition paired t[9]=3.10, p<0.05, TRP+ condition paired t[8]=2.16, p>0.06; Fig. 3). On the other hand, while non-bingers in the CTR condition did not show an increase in the Strong Desire following stress (paired t, p>0.30) and their scores were significantly lower than bingers’ at thattime point (unpaired t[10.48]=2.42, p<0.05), TRP+ diet appeared to facilitate a significant increase in craving following stress induction in non-bingers (paired t[10]=2.70, p<0.05). These effects did not appear to be related to the different level of alcohol intake of the two binge groups (ANCOVA 3-way interaction F[1,36]=6.81, p<0.05).

Figure 3.

DAQ Strong Desire with Intention to Drink factor scores (means, SEM) in bingers [B] and non-bingers [NB] in Experiment 2: Measurement were taken before [Pre-] and after [Post-] the stressful procedure in bingers [B] and non-bingers [NB] receiving tryptophan-rich [TRP+] and control [CTR] diet. * p<0.05 (paired t-test vs. Pre-) ‡ p<0.05 (independent t-test vs. Post- in NB/CTR group).

In addition to this, stress increased the scores of all four factors of the DAQ in the majority of participants (main effects of time point: Fs[1,37]>5.43, ps<0.05; Table 6).

Table 6.

Desire for Alcohol Questionnaire (DAQ) ratings of bingers [B] and non-bingers [NB] before [Pre-] and immediately after [Post-] the stress manipulation.

| Post-Diet

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Stress | Post-Stress* | ||

|

DAQ Mild Desire |

B | 18.9 (1.2) | 21.5 (1.3) |

| NB | 16.0 (1.2) | 18.6 (1.4) | |

|

DAQ Strong Desire |

B | 6.6 (0.8) | 9.2 (1.1) |

| NB | 5.6 (0.5) | 7.2 (0.8) | |

|

DAQ Negative Reinforcement |

B | 10.6 (1.3) | 13.1 (1.3) |

| NB | 10.7 (1.1) | 12.2 (1.2) | |

|

DAQ Loss of Control |

B | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.9 (0.5) |

| NB | 3.4 (0.5) | 4.4 (0.6) | |

p<0.05 – Post-stress vs. Pre-stress for all four factors (ANOVA main effect of time).

Values represent means (+/−SEM).

Discussion

In both experiments the stress manipulation successfully altered mood in this sample of heavy drinkers: stress increased feelings of anxiety, tension and anger (both experiments), and additionally increased depression and decreased positive mood (Experiment 2). These effects of stress induction on mood are comparable to the results of other studies using the TSST or other similar stress procedures (e.g. Markus et al. 2000a; Gonzalez-Bono et al. 2002; Kudielka et al. 2004; Nesic and Duka 2006; 2008). These stress-induced changes in mood were not affected by the dietary manipulation in Experiment 2 although, independently of stress, the TRP+ diet positively affected non-bingers only, reflected in the reduction of their tension level at both measuring points.

A clear physiological response to stress was also observed in both studies, with stress induction preventing the diurnal decrease in salivary cortisol levels that was observed in the non-stressful condition (Experiment 1) and producing a significant increase in cortisol secretion and heart rate compared to the pre-stress baseline (Experiment 2). TRP+ diet appeared to have a beneficial effect on the cardiovascular stress response in non-binge drinkers only, blocking the stress-induced increase in heart rate in Experiment 2.

While in Experiment 1 stress did not appear to induce a significant effect on craving in the experimental sample, possibly due to a small number of participants, introducing a pre-stress baseline measurement in Experiment 2 revealed that ratings for all four craving factors were increased by stress.

As predicted, binge drinkers displayed in both experiments a significantly greater increase in self-reported ‘Strong Desire with Intentions to Drink’ after stress than their non-binge drinking counterparts. TRP+ diet appeared to block this stress-related increase in craving in binge drinkers. In contrast, the TRP+ diet facilitated stress-induced increase in craving in the non-bingers. These findings confirm the suggestions from the pre-clinical literature that stress modulates alcohol-related behaviours via a serotonergic mechanism (Lê and Shaham 2002).

Bingers and non-bingers: distinct populations

Binge drinkers were characterized by more pronounced negative mood and showed higher negative expectancy of alcohol outcomes, particularly in terms of heightened risk and aggression (Experiment 1 and 2).

Bingers were also characterized by lower Self-Directedness character dimension scores (Experiments 1 and 2), suggesting that they possess a reduced ability for self-reflection (Schuerbeek et al. 2011) and maintenance of goal-directed behaviour (Cloninger et al. 1993). Additionally, lower trait Persistence, another indicator of a dysfunction in the fronto-striatal reward circuits (Gusnard et al. 2003) was observed in binge drinkers, albeit in Experiment 2 only.

A reduced ability to regulate goal-directed behaviours is a commonly accepted feature of compulsive drug use and stress has been suggested as one of the mechanisms that underlie this transition from goal-driven to habit-driven behaviour that underlies addictive behaviour (Schwabe et al. 2011). The observed differences in the personality profiles of the two groups of drinkers therefore confirm the suggestion that bingers may be at an increased risk of developing alcohol dependence (Crews and Boettiger 2009).

Independently of stress, bingers were characterized by more pronounced negative mood in both experiments although this was not additionally increased by stress, possibly due to a ceiling effect. Bingers also reported higher negative reinforcement craving albeit in Experiment 1 only. Taken together, these findings are in line with the suggestion that drinking to escape negative affect significantly predicts binge drinking (Williams and Clark 1998).

The most consistent effect observed in the present experiments is that stress induced greater strong desire with intentions to drink in bingers compared to non-bingers. This may suggest that the stress-induced disinhibition of the incentive value of alcohol, rather than its negative reinforcement qualities, represents a more important mechanism that mediates stress-induced drinking in bingers.

The differences between bingers and non-bingers in terms of their mood and physiological reactivity to stress, however, were less consistent. Although bingers in Experiment 1 appeared to be more susceptible to anxiety-inducing effects of stress than their non-bingeing counterparts, this difference was not observed in Experiment 2. In fact, in the latter experiment, non-bingers appeared to be more negatively affected by stress, displaying heightened cardiovascular reactivity during the stress induction procedure. This difference in stress reactivity of bingers between the two studies is difficult to understand. Potential explanations for this discrepancy may be that the overall alcohol intake level of participants was higher in Experiment 1 than in Experiment 2; also binge drinkers in Experiment 1 had particularly high STAI-trait anxiety scores (Table 2). Further studies are needed to elucidate the differential reactivity of bingers and non-bingers to stress.

The present studies suggest that, although bingers may not necessarily be more susceptible than non-bingers to the effects of stress on mood and physiological responses, they nevertheless consistently show a greater propensity to stress-induced craving with intention to drink. This finding is in line with the suggestions that repeated intoxication followed by withdrawals (‘hangovers’) may increase the occurrence of alcohol-related behaviours (Duka et al. 2004). This is the first demonstration of its kind in humans and adds support to the theories which highlight binge drinking as a vulnerability factor for the development of alcoholism.

Tryptophan manipulations – both enhancement and depletion – appear to produce behavioural effects in individuals who already suffer from a 5-HT dysfunction, such as those prone to depression (Young et al. 1985; Delgado et al. 1990), and recent studies investigating the role of the serotonin transporter promoter gene (5-HTTLPR) polymorphism suggest that carriers of the short allele display greater vulnerability to serotonergic modulation, stress, and depression and anxiety (see Markus and Firk 2009 for a detailed discussion). While the differential effects of stress and tryptophan enhancement on the two binge groups in Experiment 2 may be taken as an index of difference in their serotonergic system regulation (Dougherty et al. 1999), the nature of this difference is not clear and further studies are needed to elucidate it.

The role of serotonin in modulating stress reactivity

The findings of Experiment 2 suggest a differential involvement of 5-HT in mediating stress reactivity and, more specifically, alcohol-related behaviours, in binge and non-binge drinkers. The double dissociation between dietary effects on mood (independent of stress) and craving (in response to stress) in bingers and non-bingers suggests that serotonergic pathways may be differentially involved in modulating the two functions (mood and alcohol-related behaviours). Although the role of serotonin in modulating stress responsiveness (subjective and physiological) is to promote resilience to mood-lowering effects of adverse situations (Deakin and Graeff 1991), this may be different from the yet unclear role of serotonin in modulating stress-induced alcohol-related behaviour.

Indeed, the increased motivation to drink following tryptophan enhancement seen in non-bingers is in line with the role of serotonin in potentiating the activation of the mesolimbic DA system, which is thought to mediate incentive properties of alcohol and other appetitive stimuli (Di Chiara and Imperato 1988; Ikemoto and Panksepp 1999; McBride et al. 1999). Such an explanation can also account for the fact that the TRP+ diet enhanced craving for alcohol only after stress induction, since activity of dorsal raphe serotonergic neurones is increased during arousing situations such as stress (Jacobs and Fornal 1999), and stimulation or inhibition of dorsal raphe neurones was found to increase or reduce, respectively, DA release into nucleus accumbens (McBride et al. 1993). Thus the present findings in non-bingers may be explained in terms of a specific stimulatory effect of tryptophan enhancement on the incentive value of alcohol under stress. On the other hand, it is possible that binge drinkers already have a sensitised incentive system (Stephens and Duka, 2008) which is why tryptophan enhancement, at least as given here, may not be able to increase this activation further.

The complexity of serotonergic modulation of incentive value of alcohol was highlighted by Berggren and colleagues (2001), who demonstrated that pharmacological enhancement of 5-HT function effectively reduced alcohol consumption in heavy drinkers who showed increased release of prolactin in response to the fenfluramine challenge (an index of unimpaired serotonergic function), while in those with more evident 5-HT impairment (i.e. a low prolactin responders to fenfluramine) the same treatment had no effect or even promoted alcohol consumption. In a study with healthy volunteers, Roiser and colleagues (2006) reported increased incentive motivation following tryptophan depletion in individuals with the long allele of the serotonin transporter promoter gene (5-HTTLPR) while the treatment had the opposite effect (i.e. reduced motivation) in individuals with the short allelic variation of this gene. These findings may account for the unexpected enhancement of craving in stressed non-bingers following tryptophan enhancement in the present studies. Studies examining baseline serotonin function in bingers and non-bingers, such as Berggren and colleagues’ fenfluramine challenge study with heavy drinkers (Berggren et al. 2001), or examining 5-HTTLPR polymorphism, are needed to characterize stress reactivity as well as serotonergic function of the two populations.

Unlike the personality profile differences between bingers and non-bingers, the differences in their craving response to stress and dietary manipulation appeared to be independent of individuals’ habitual level of alcohol intake, confirming the hypothesis that differences in emotional reactivity are related to the pattern of drinking (frequent alcohol intoxication followed by hangover/withdrawal) rather than the absolute quantity of alcohol consumption.

Implications and conclusions

The findings of the present series of experiments indicate that heavy drinkers who binge and those who do not binge are two distinct populations. Bingers consistently displayed a personality profile suggestive of a reduced ability to regulate goal-directed behaviour – a known factor in the aetiology and maintenance of addictive disorders, and were more susceptible to negative mood and stress-induced craving for alcohol.

The data from Experiment 2 are among the first demonstrations in human drinkers that serotonin is involved in mediating the effects of stress on alcohol-related behaviours. The effect of serotonin enhancement using dietary tryptophan loading, however, was complex and, as predicted, depended on individuals’ pattern of alcohol use. Tryptophan enhancement selectively blocked the stress-induced increase in the strong desire and intentions to drink alcohol in binge drinkers, while it actually tended to promote an increase in this type of craving in stressed non-binge drinking individuals.

These findings suggest that individuals’ pattern of drinking rather than the total quantity of alcohol consumed per week is a factor that may confer differential susceptibility to the development of alcoholism in social drinkers and also influence responsiveness to serotonergic therapy for alcohol abuse. This may shed light on inconsistent reports in the literature regarding the effectiveness of serotonergic pharmacotherapy in the treatment of alcohol dependence (Kenna 2010).

The results of Experiment 2 clearly indicate that use of α-lactalbumin supplements as means of improving stress resilience and reducing susceptibility to alcoholism may be effective in individuals who binge drink. The results also emphasise the importance of having experimentally-derived/accurate diagnostic criteria for binge drinking, because in heavy drinkers who drink more steadily (i.e. who do not binge drink), the use of such supplements is not only unfounded but may also have the negative consequence of increasing the incentive value of alcohol during stress. Furthermore, considering the sensitivity of the serotonergic system to dietary composition (Yokogoshi and Wurtman 1986), the present findings highlight the need to take dietary factors into account when evaluating vulnerability to alcoholism in heavy social drinkers.

Apart from the small group size in Experiment 1, another possible limitation of the present experiments is the fact that there was a wide range of habitual alcohol consumption in both study samples, which might have confounded some of the findings. However, the two binge groups differed significantly in terms of their habitual level of alcohol intake only in Experiment 2, and even then the majority of the observed effects appeared to be due to the pattern of drinking, rather than the absolute quantity of alcohol participants usually consumed during a week.

Binge drinking is related to increased occurrence of acute as well as longer term behavioural and health problems (Wechsler et al. 1999; Naimi et al. 2003) and the high incidence of this pattern of heavy drinking in the United Kingdom has significant health, social and economic consequences (Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit 2004). It is therefore essential to understand the mechanisms that mediate this type of behaviour, particularly in relation to stress, in order to support the development of strategies aimed at reducing the prevalence of binge drinking behaviour as well as preventing it from escalating into alcohol dependence.

In conclusion the present experiments further support the hypothesis that stress influences alcohol-related behaviour via an activation of the positive incentive properties of alcohol rather than its negative reinforcement properties, possibly via a disinhibitory effect. The present experiments also highlight the importance of the serotonergic system in underlying the stress-induced changes. Further studies more directly exploring the cognitive inhibitory effect of stress on the incentive value of alcohol are needed to elucidate the relative importance of these mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Overseas Research Studentship for postgraduate studies and partly by a grant to TD from the National Institute of Health (GBNEU0306A_US). ‘Vivinal Alpha’ (α-lactalbumin-enriched whey protein powder) was provided by Broculo Domo Ingredients, Netherlands. Butter powder and sodium caseinate provided by Garrett Ingredients Ltd, UK, and maltrodextrine provided by Cerestar, UK. Our thanks to Drs Abi Rose and Sam Knowles who helped with the food preparation, and to Dr Abdullah Badawy from Biomedical Research Laboratories, Whitchurch Hospital, Cardiff, for advice and analysis of blood samples in the pilot test of the dietary tryptophan manipulation.

List of References

- Berggren U, Eriksson M, Fahlke C, Balldin J. Relationship between central serotonergic neurotransmission and reduction in alcohol intake by citalopram. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63:263–267. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binz U, Wendt G. KUSTA: Brief Rating Scale for Mood and Activation. In: AMDP, CIPS, editor. Rating Scales in Psychiatry. Weinheim, West Germany: Beltz Test; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Sonne SC. The role of stress in alcohol use, alcoholism treatment, and relapse. Alcohol Res Heal. 1999;23:263–271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese GR, Chu K, Dayas CV, et al. Stress enhancement of craving during sobriety: a risk for relapse. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:185–195. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000153544.83656.3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Hong K, Bergquist K, Sinha R. Gender differences in response to emotional stress: an assessment across subjective, behavioral, and physiological domains and relations to alcohol craving. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:1242–1250. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5274–5278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:975–990. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240059008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Przybeck TR, Svrakic DM, Wetzel RD. The Temperament and Character Inventory (TCI): A guide to its development and use. Center for Psychobiology of Personality. St Louis, Mo: Center for Psychobiology of Personality; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Saladin ME, Drobes DJ, et al. Trauma and substance cue reactivity in individuals with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and cocaine or alcohol dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002;65:115–127. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(01)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Boettiger CA. Impulsivity, frontal lobes and risk for addiction. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;93:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Ruan WJ. The association between stress and drinking: Modifying effects of gender and vulnerability. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40:453–460. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deakin JF, Graeff FG. 5-HT and mechanisms of defence. J Psychopharmacol. 1991;5:305–315. doi: 10.1177/026988119100500414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado PL, Charney DS, Price LH, et al. Serotonin function and the mechanism of antidepressant action. Reversal of antidepressant-induced remission by rapid depletion of plasma tryptophan. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:411–418. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1990.01810170011002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health. The health of the nation – a strategy for health in England. London: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- De Wit H, Söderpalm AHV, Nikolayev L, Young E. Effects of acute social stress on alcohol consumption in healthy subjects. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1270–1277. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000081617.37539.D6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Bjork JM, Marsh DM, Moeller FG. Influence of trait hostility on tryptophan depletion-induced laboratory aggression. Psychiatry Res. 1999;88:227–232. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(99)00088-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duka T, Gentry J, Malcolm R, Ripley TL, Borlikova G, Stephens DN, et al. Consequences of multiple withdrawals from alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:233–246. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000113780.41701.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Powell H. Stress increases attentional bias for alcohol cues in social drinkers who drink to cope. Alcohol Alcohol. 2007;42:560–566. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ. A comparison of the effects of dorsal or median raphe injections of 8-OH-DPAT in three operant tasks measuring response inhibition. Behav Brain Res. 1993;54:187–197. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(93)90078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher PJ, Tampakeras M, Yeomans JS. Median raphe injections of 8-OH-DPAT lower frequency thresholds for lateral hypothalamic self-stimulation. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1995;52:65–71. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(94)00441-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Bergquist KL, Hong K-I, Sinha R. Stress-induced and alcohol cue-induced craving in recently abstinent alcohol-dependent individuals. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Stroot EA, Kaplan D. Comprehensive effects of alcohol: Development and psychometric assessment of a new expectancy questionnaire. Psychol Assess. 1993;5:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfield GS, Adamo KB, Rutherford J, Legg C. Stress and the relative reinforcing value of food in female binge eaters. Physiol Behav. 2008;93:579–87. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Bono E, Rohleder N, Hellhammer DH, et al. Glucose but not protein or fat load amplifies the cortisol response to psychosocial stress. Horm Behav. 2002;41:328–333. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2002.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gusnard DA, Ollinger JM, Shulman GL, et al. Persistence and brain circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3479–3484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0538050100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins RL, Marlatt GA. Fear of interpersonal evaluation as a determinant of alcohol consumption in male social drinkers. J Abnorm Psychol. 1975;84:644–651. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.84.6.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S, Panksepp J. The role of nucleus accumbens dopamine in motivated behavior: a unifying interpretation with special reference to reward-seeking. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1999;31:6–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BL, Fornal CA. Activity of serotonergic neurons in behaving animals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:9S–15S. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenna GA. Medications acting on the serotonergic system for the treatment of alcohol dependent patients. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2126–2135. doi: 10.2174/138161210791516396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, Hellhammer DH. The “Trier Social Stress Test”–a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology. 1993;28:76–81. doi: 10.1159/000119004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Schommer NC, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. Acute HPA axis responses, heart rate, and mood changes to psychosocial stress (TSST) in humans at different times of day. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:983–992. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê AD, Poulos CX, Harding S, Watchus J, Juzytsch W, Shaham Y. Effects of naltrexone and fluoxetine on alcohol self-administration and reinstatement of alcohol seeking induced by priming injections of alcohol and exposure to stress. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21:435–444. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê A, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of relapse to alcohol in rats. Pharmacol Ther. 2002;94:137–156. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Weiss F. Additive effect of stress and drug cues on reinstatement of ethanol seeking: exacerbation by history of dependence and role of concurrent activation of corticotropin-releasing factor and opioid mechanisms. J Neurosci. 2002;22:7856–7861. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-18-07856.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love A, James D, Willner P. A comparison of two alcohol craving questionnaires. Addiction. 1998;93:1091–1102. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.937109113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus CR, De Raedt R. Differential effects of 5-HTTLPR genotypes on inhibition of negative emotional information following acute stress exposure and tryptophan challenge. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:819–826. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus CR, Firk C. Differential effects of tri-allelic 5-HTTLPR polymorphisms in healthy subjects on mood and stress performance after tryptophan challenge. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:2667–2674. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus CR, Panhuysen G, Jonkman LM, Bachman M. Carbohydrate intake improves cognitive performance of stress-prone individuals under controllable laboratory stress. Br J Nutr. 1999;82:457–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus CR, Panhuysen G, Tuiten A, Koppeschaar H, Fekkes D, Peters ML. Does carbohydrate-rich, protein-poor food prevent a deterioration of mood and cognitive performance of stress-prone subjects when subjected to a stressful task? Appetite. 1998;31:49–65. doi: 10.1006/appe.1997.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus CR, Olivier B, Panhuysen G, Van der Gugten J, Alles MS, Tuiten A, et al. The bovine protein a-lactalbumin increases the plasma ratio of tryptophan to the other large neutral amino acids, and in vulnerable subjects raises brain serotonin activity, reduces cortisol concentration, and improves mood under stress. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000a;71:1536–1544. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.6.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus R, Panhuysen G, Tuiten A, Koppeschaar H. Effects of food on cortisol and mood in vulnerable subjects under controllable and uncontrollable stress. Physiol Behav. 2000b;70:333–342. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus CR, Olivier B, De Haan EHF. Whey protein rich in alpha-lactalbumin increases the ratio of plasma tryptophan to the sum of the other large neutral amino acids and improves cognitive performance in stress-vulnerable subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:1051–1056. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.6.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA. A Cognitive-Behavioral Model of the Relapse Process. In: Krasnegor NA, editor. Behavioral Analysis and Treatment of Substance Abuse. NIDA Research Monographs; 1979. pp. 191–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride WJ, Murphy JM, Yoshimoto K, et al. Serotonin Mechanisms in Alcohol-Drinking Behavior. Drug Dev Res. 1993;30:170–177. [Google Scholar]

- McBride WJ, Murphy JM, Ikemoto S. Localization of brain reinforcement mechanisms: intracranial self-administration and intracranial place-conditioning studies. BehavBrain Res. 1999;101:129–152. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair DM, Lorr M, Droppleman LF. Profile of Mood States (POMS) Educ Ind Test Serv 1971 [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian A, Russell JA. A questionnaire measure of habitual alcohol use. Psychol Rep. 1978;43:803–806. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1978.43.3.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PM, Hersen M, Eisler RM, Hilsman G. Effects of social stress on operant drinking of alcoholics and social drinkers. Behav Res Ther. 1974;12:67–72. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(74)90094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, et al. Binge drinking among US adults. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:70–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesic J, Duka T. Gender specific effects of a mild stressor on alcohol cue reactivity in heavy social drinkers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;83:239–248. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesic J, Duka T. Effects of stress on emotional reactivity in hostile heavy social drinkers following dietary tryptophan enhancement. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:151–162. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesic J, Morgan CJ, Badawy AA-B, Duka T. Effects of tryptophan-enriched diet and stress on serum tryptophan levels and mood: the role of trait aggression. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17:A16. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Lang AR, Atkeson B, Murphy DA, Gnagy EM, Greisner AR, et al. Effects of deviant child behavior on parental distress and alcohol consumption in laboratory interactions. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1997;25:413–424. doi: 10.1023/a:1025789108958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Le Moal M. Glucocorticoids as a biological substrate of reward: physiological and pathophysiological implications. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1997;25:359–372. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Le Moal M. The role of stress in drug self-administration. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998;19:67–74. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(97)01115-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit CO. Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy for England. London, UK: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Roiser J, Blackwell A, Cools R, Clark L, Rubinsztein D, Robbins T, et al. Serotonin transporter polymorphism mediates vulnerability to loss of incentive motivation following acute tryptophan depletion. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2264–2272. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaechter JD, Wurtman RJ. Serotonin release varies with brain tryptophan levels. Brain Res. 1990;532:203–210. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91761-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]