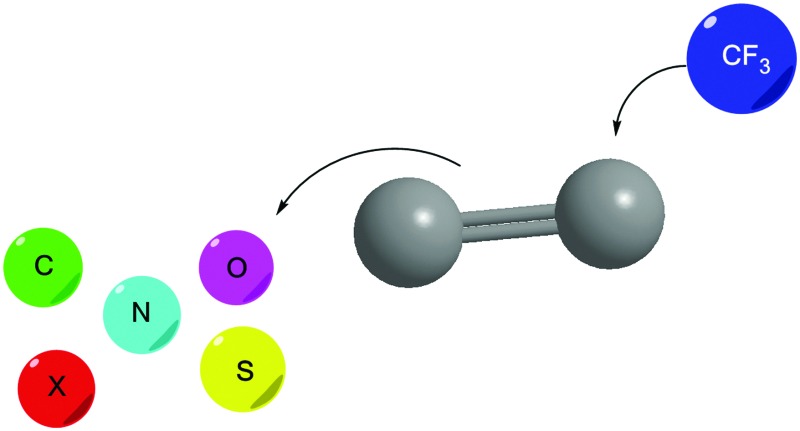

This review summarizes recent methodologies for the simultaneous formation of C–CF3 and C–C or C–heteroatom bonds by formal addition reactions to alkenes.

This review summarizes recent methodologies for the simultaneous formation of C–CF3 and C–C or C–heteroatom bonds by formal addition reactions to alkenes.

Abstract

In the last few years, the efficient introduction of trifluoromethyl groups in organic molecules has become a major research focus. This review highlights the recent developments enabling the incorporation of CF3 groups across unsaturated moieties, preferentially alkenes, and the mechanistic scenarios governing these transformations. We have specially focused on methods involving the simultaneous formation of C–CF3 and C–C or C–heteroatom bonds by formal addition reactions across π-systems, as such difunctionalization processes hold valuable synthetic potential.

Introduction

The presence of C–F bonds in organic molecules has a profound effect on properties such as lipophilicity, permeability and metabolic stability so that more than 20% of the current approved drugs contain at least one fluorine atom. 1,2 Thus, in the past few years, the efficient introduction of fluorine atoms or fluorine containing groups in pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals and functional materials has turned into a major research focus for synthetic chemists. 3–10 Transition metal catalyzed trifluoromethylation reactions are the most popular route to introduce CF3 groups into common building blocks, although recently, metal-free processes have also been described to carry out this transformation under alternative, and sometimes even complementary, conditions. In this context, double bonds can be considered privileged starting materials, as they are easily accessible and robust feedstocks, but are also amenable to flexible functionalization. This review highlights the recent developments enabling the incorporation of CF3 groups across unsaturated moieties and the mechanistic scenarios governing these transformations. We have preferentially focused on alkenes as starting materials, with special attention on methods that involve the simultaneous formation of C–CF3 and C–C or C–heteroatom bonds by formal addition reactions across π-systems.

1. Alkene trifluoromethylation

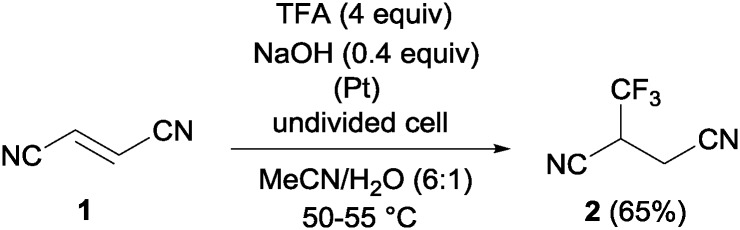

Pioneering studies describing the electrochemical hydrotrifluoromethylation of alkenes were reported in the late 80's. 11,12 Aliphatic trifluoromethylated compounds could be efficiently prepared by electrochemical oxidation of trifluoroacetic acid, as TFA is one of the most economic and easily available sources of CF3. 13 Fumaronitrile 1 and related activated olefins were transformed into the 2-trifluoromethylsuccinyl derivatives by oxidation of trifluoroacetic acid in platinum electrodes in a mixture of acetonitrile and water at 50–55 °C (Scheme 1). 14 The trifluoromethyl radicals generated in the anode recombined with the succinyl radicals produced at the cathodic site, leading to the formation of products 2.

Scheme 1. Hydrotrifluoromethylation of fumaronitrile 1.

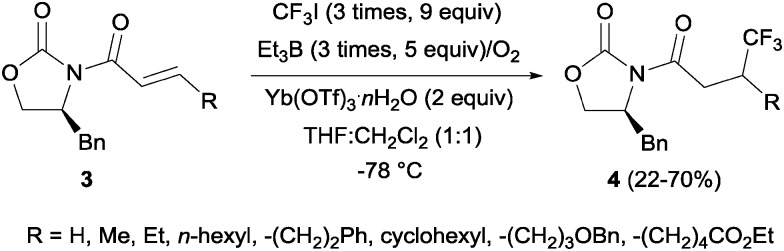

In 2002, Langlois et al. showed the hydrotrifluoromethylation of unactivated alkenes with CF3SO2Na by electrochemical oxidation albeit with low chemoselectivity. 15 Later, the hydrotrifluoromethylation of α,β-unsaturated ketones in the presence of RhCl(PPh3)3 and Et2Zn was reported. In this reaction, CF3I was employed as a trifluoromethyl source and α-trifluoromethylated carbonyl compounds were obtained in moderate yields. 16 The authors proposed the formation of a rhodium hydride complex by reaction of RhCl(PPh3)3 and Et2Zn. The oxidative addition of CF3I occurred on the rhodium enolate, which furnished the product by reductive elimination. In contrast, the reaction of α,β-unsaturated acyl-oxazolidinones 3 in the presence of Et3B under oxidative conditions (O2) enabled the synthesis of chiral β-trifluoromethylated amino acids (Scheme 2). 17 The proposed mechanism involves the generation of a CF3-radical, which undergoes Michael addition to form a diethylboron enolate whose in situ hydrolysis led to the observed product 4 with complete β-regioselectivity but no diastereoselectivity.

Scheme 2. Trifluoromethylation of acyl-oxazolidinones.

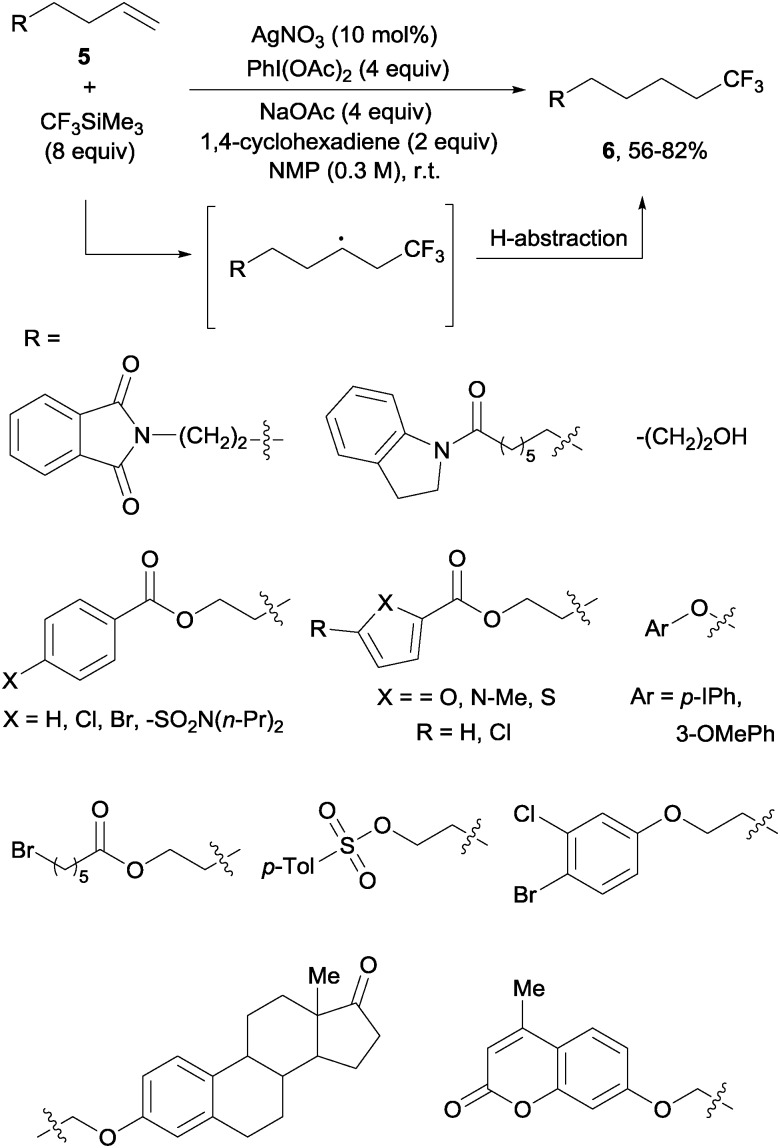

In contrast to the previously described methods, the hydrotrifluoromethylation reaction of unactivated olefins remained, until recently, much less explored. The groups of Qing, 18 Gouverneur 19 and Nicewicz 20 described, almost simultaneously, the hydrotrifluoromethylation of unactivated alkenes. The reactions, operating under mild conditions, enabled a net “fluoroform” addition across alkenes and alkynes in a regioselective manner obtaining exclusively in most cases anti-Markovnikov regioisomers. Qing's protocol required AgNO3 as a catalyst, CF3SiMe3 as a trifluoromethylating agent and PhI(OAc)2 as an oxidant. These conditions were amenable to monosubstituted alkenes 5 which produced trifluoromethyl alkanes 6 at room temperature (Scheme 3). Preliminary control experiments seemed to point towards the formation of CF3 radical species under the above-mentioned conditions. Upon addition of the CF3 radical to the double bond, hydrogen is likely abstracted from 1,4-cyclohexadiene to give the observed products.

Scheme 3. Silver-catalyzed hydrotrifluoromethylation of unactivated alkenes.

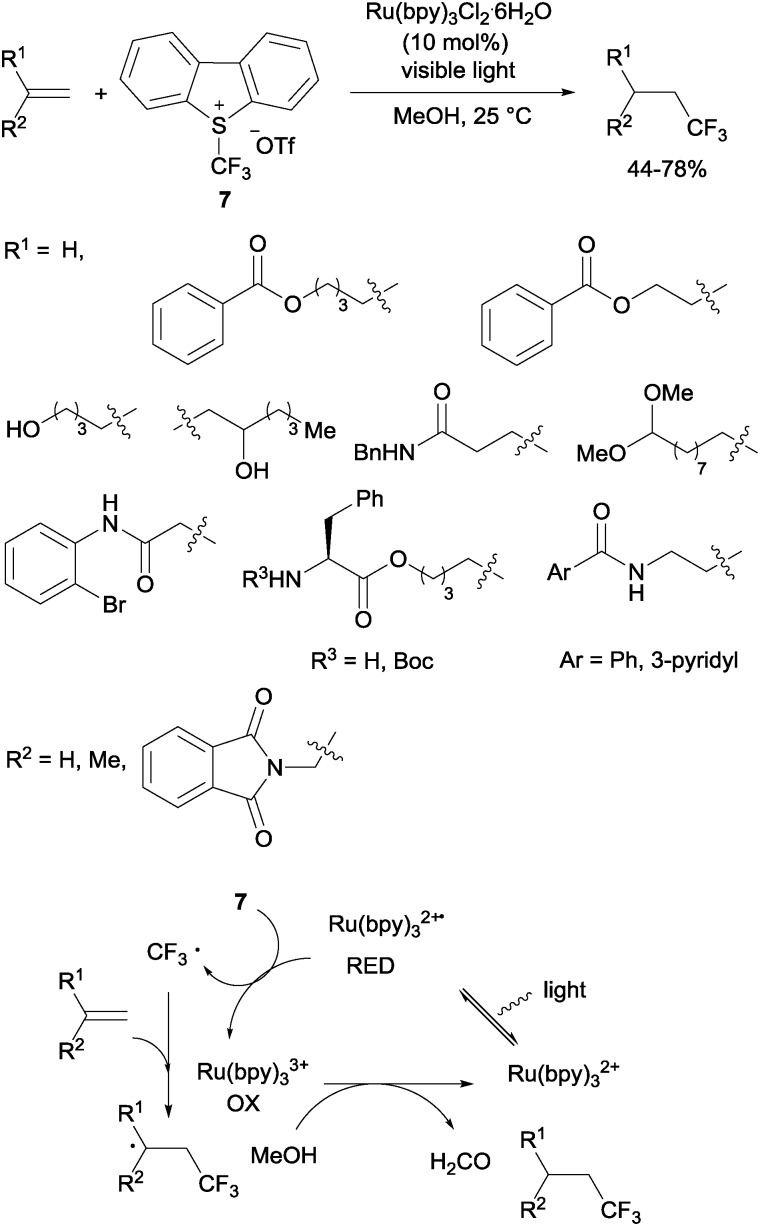

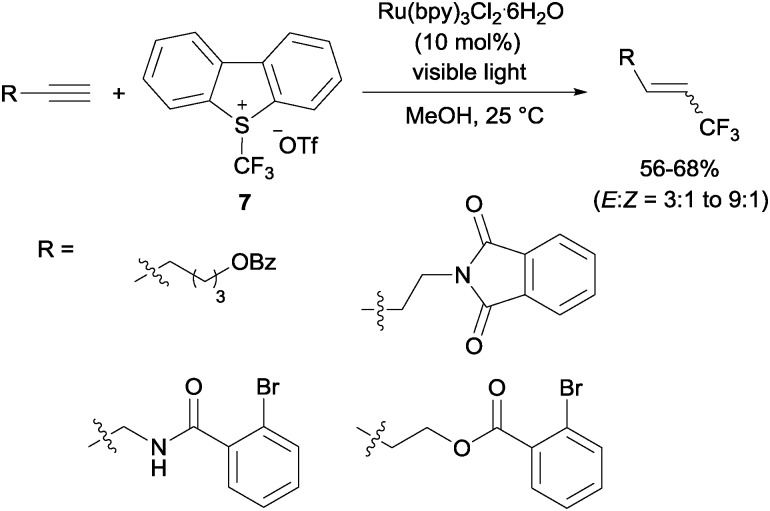

Gouverneur's hydrotrifluoromethylation of unactivated terminal and geminally disubstituted alkenes (Scheme 4) and alkynes (Scheme 5) could also be carried out at room temperature using visible-light-activated Ru(bpy)3Cl2·6H2O, Umemoto's reagent (7) as a CF3 source and methanol as a hydrogen donor according to the mechanism proposed in Scheme 4. 19

Scheme 4. Hydrotrifluoromethylation of unactivated alkenes and the proposed reaction mechanism.

Scheme 5. Hydrotrifluoromethylation of alkynes.

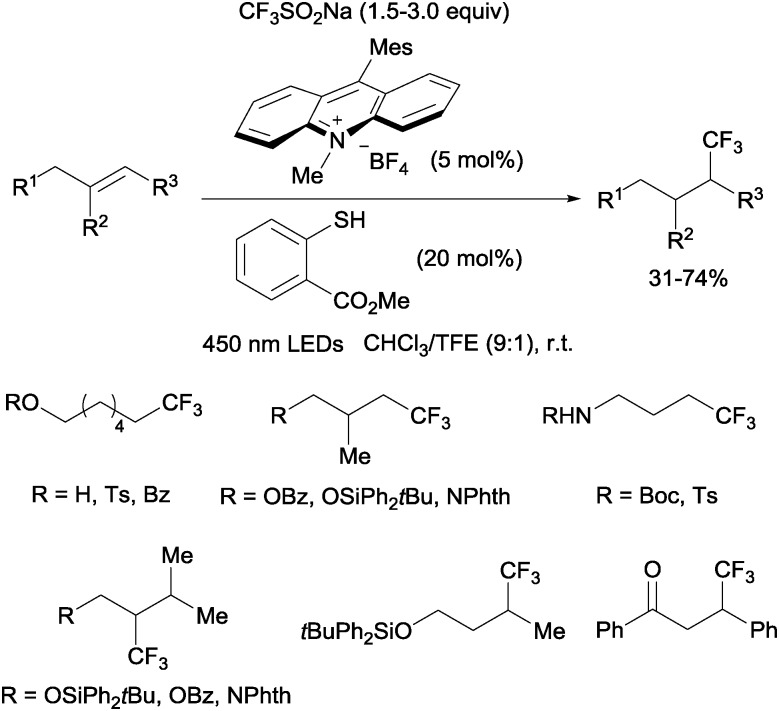

Nicewicz developed a metal-free photoredox process for the hydrotrifluoromethylation of unactivated mono-, di- and trisubstituted alkenes shortly thereafter. 20 The Langlois reagent (CF3SO2Na) was used as a CF3 source and N-methyl-9-mesityl acridium as a photoredox catalyst. Methyl-thiosalicylate could act as a hydrogen donor in the case of aliphatic alkenes (Scheme 6) whereas thiophenol seems to be better suited for styrene substrates.

Scheme 6. Metal-free hydrotrifluoromethylation of aliphatic mono-, di-, and trisubstituted alkenes.

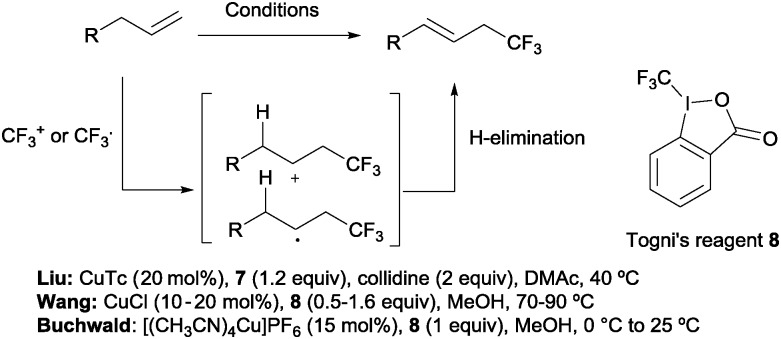

Beyond hydrotrifluoromethylation reactions, the allyl trifluoromethylation of alkenes has also received significant attention in recent years. Thus, the groups of Buchwald, 21 Wang 22 and Liu 23 reported the allylic trifluoromethylation of unactivated olefins with copper salts and the Togni (8) or the Umemoto (7) reagent as a trifluoromethyl source. Although the exact mechanism for these transformations is yet to be elucidated, radical or cationic species generated upon CF3 addition across the terminal double bond have been proposed as likely intermediates. Subsequent H-elimination delivers the observed products (Scheme 7).

Scheme 7. Allyl trifluoromethylation of unactivated alkenes.

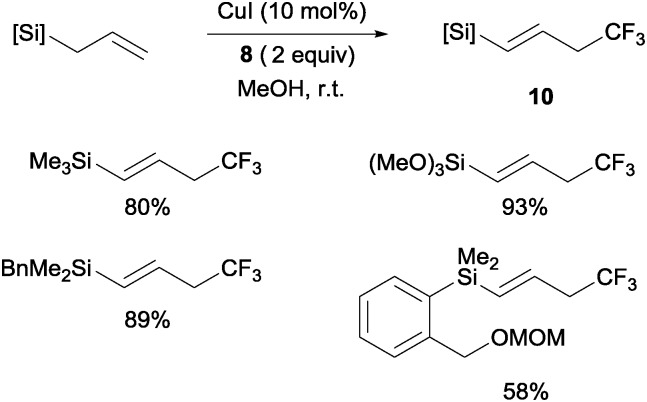

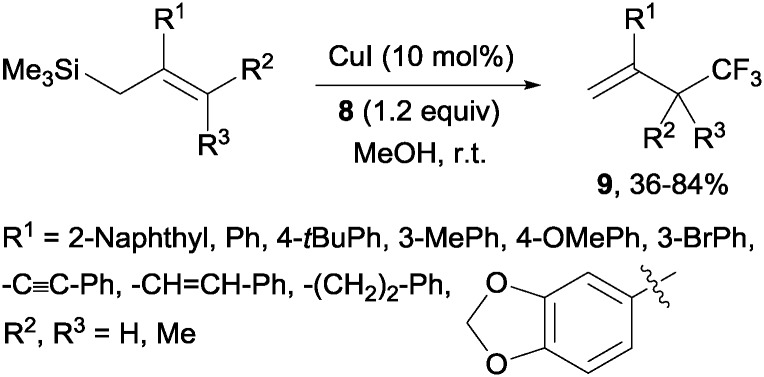

Copper(i)-catalyzed trifluoromethylations of allylsilanes with Togni reagent 8 under mild conditions were also described by the groups of Sodeoka and Gouverneur. 24,25 Allylic trifluoromethylated compounds 9 were obtained with 2-substituted allylsilanes as starting materials (Scheme 8). When the allylsilanes were not substituted in the 2-position, the corresponding vinyl silane derivatives 10 could be isolated in excellent selectivities and yields (Scheme 9).

Scheme 8. Trifluoromethylation of 2-substituted allylsilanes.

Scheme 9. Copper-catalyzed synthesis of trifluoromethylated vinylsilanes.

2. Alkene trifluoromethylation and C–C bond formation

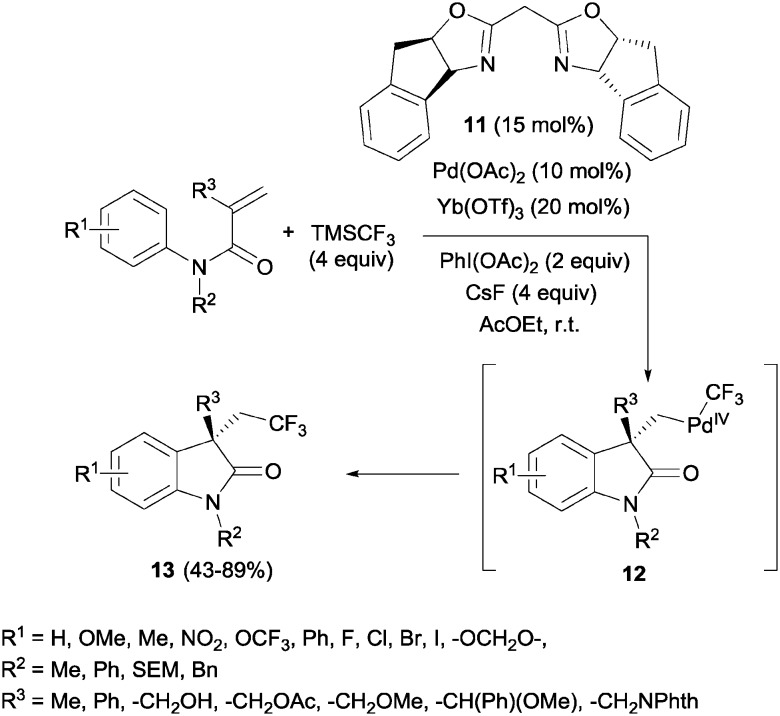

The simultaneous formation of C–C and C–CF3 bonds represents an attractive strategy for the carbodifunctionalization of alkenes. A pioneering example was reported by Liu's group in 2012. A palladium-catalyzed intramolecular oxidative aryltrifluoromethylation of activated alkenes was developed so that CF3-substituted oxindoles 13 could be obtained in excellent yields. 26 Upon π-activation of the olefin by the metal and cyclization with the aromatic ring, the Pd(ii) intermediate was oxidized to Pd(iv) in the presence of PhI(OAc)2. The system CsF/TMSCF3 worked as a nucleophilic source of CF3, triggering the ligand exchange on the Pd(iv) intermediate 12 prior to the reductive elimination, furnishing the new Csp3–CF3 bond (Scheme 10).

Scheme 10. Synthesis of oxindoles by Pd-catalyzed aryltrifluoromethylation of alkenes.

Later, Sodeoka's group reported the combination of CuI and Togni reagent 8 to access trifluoromethylated oxindoles in excellent yields from similar acrylanilide starting materials. 27 The use of Langlois' reagent (CF3SO2Na) and TBHP in the presence of Cu(ii) in aqueous media at room temperature also furnished this type of compounds through a radical process. 28 The recycling of the aqueous medium was possible at least 5 times with only a slight decrease in the isolated yields. A similar process but in a mixture of organic solvents was also developed. 29

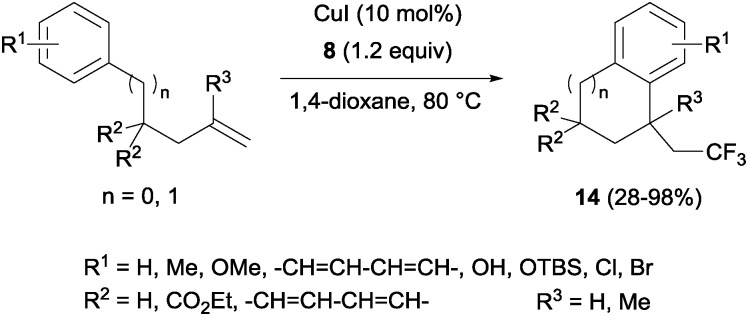

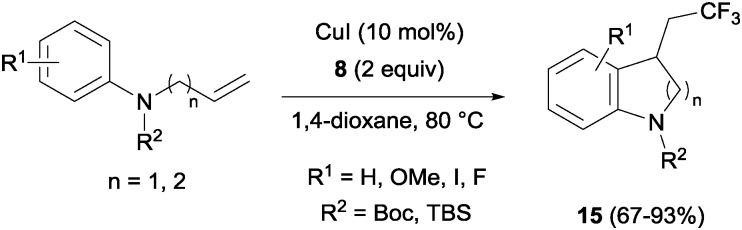

The combination of copper salts and Togni reagent 8 enabled Sodeoka's group to synthesize trifluoromethylated carbo- (14, Scheme 11) and heterocycles (15, Scheme 12) in the first examples of aryltrifluoromethylations on unactivated olefins. 30 In this case, the six membered ring formation seemed to be faster than the five membered ring one, an acceleration that could be explained by a more favourable orbital interaction between the aryl ring and alkene in the transition state for the former case.

Scheme 11. Synthesis of carbocycles by trifluoromethylation of alkenes.

Scheme 12. Copper-catalyzed carbotrifluoromethylation of N-protected allyl- and homoallylaniline derivatives.

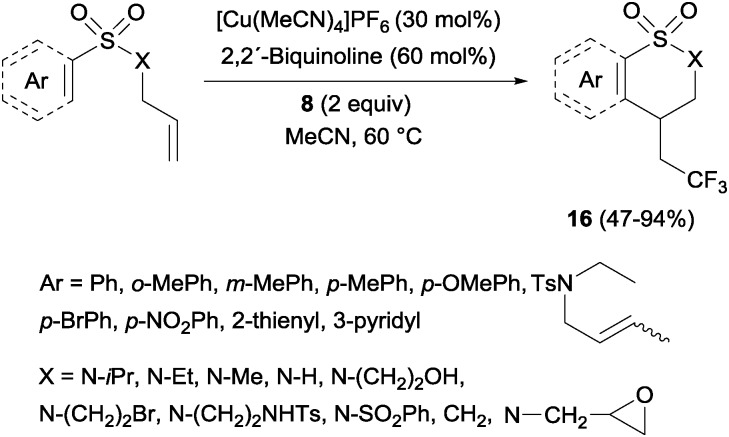

Trifluoromethylated 1,2-benzothiazinane dioxide derivatives 16 could be obtained by a similar tandem trifluoromethylation-annulation reaction with N-allyl-N-sulfonylamines as substrates also in the presence of copper and Togni reagent 8 (Scheme 13). 31

Scheme 13. Trifluoromethylation–cyclization on N-allyl-N-sulfonylamines.

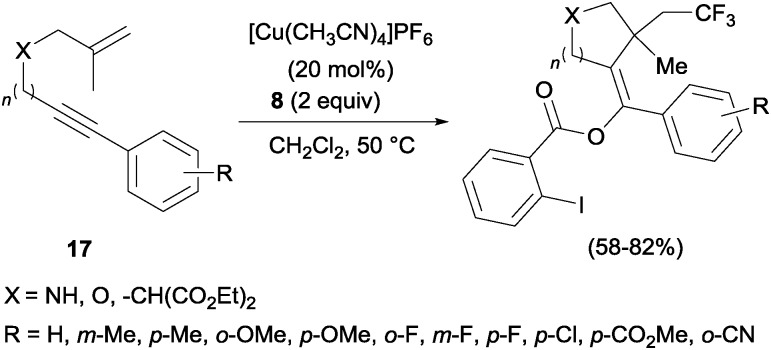

In the presence of catalytic amounts of copper and Togni reagent 8, 1,6-enynes 17 delivered substituted hydrofurans, tetrahydropyranes, piperidines and pyrrolidines as a result of a tandem trifluoromethylation–cyclization process (Scheme 14). 32 Upon addition of 2-iodo benzoic acid released from Togni's reagent, the triple bond seemed to work here as a nucleophile generating 5- or 6-exo-dig carbo- and heterocycles in a highly regioselective manner.

Scheme 14. Trifluoromethylation–cyclization of enynes.

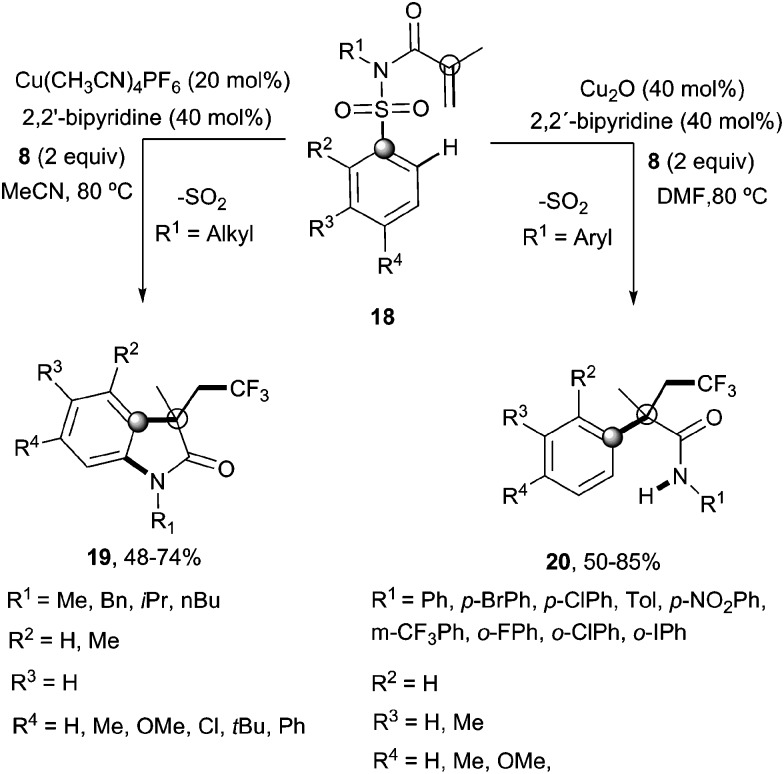

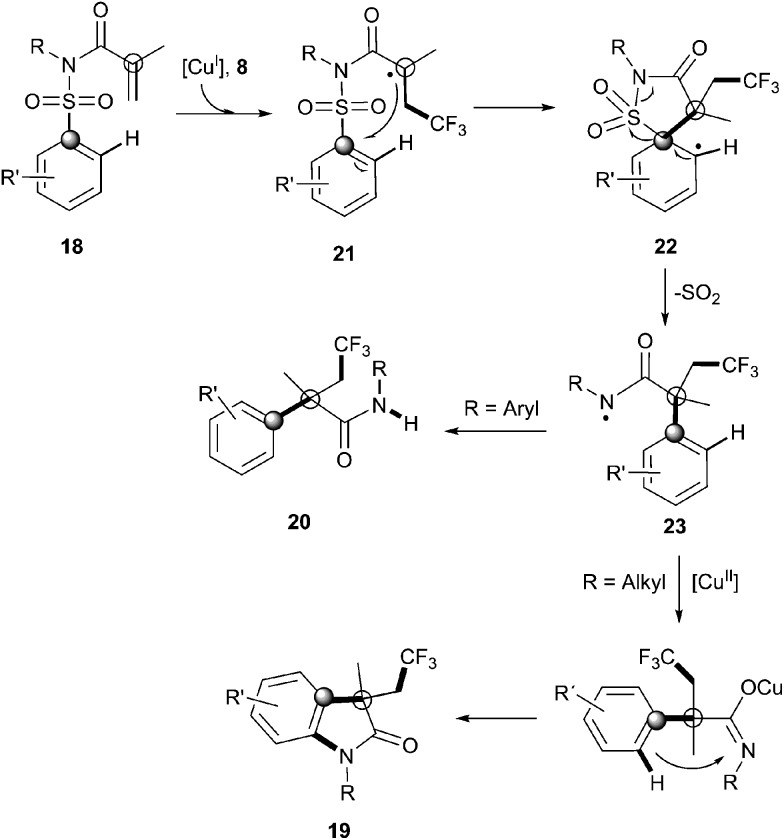

Recently, Nevado's group described an aryltrifluoromethylation of alkenes in which the reactivity of acrylamides 18 was modulated by the substituent on the nitrogen atom. 33 N-Alkyl substituted substrates furnished trifluoromethylated oxindoles 19 in 48–74% yield when [Cu(MeCN)4]PF6 was used as a catalyst and 2,2′-bipyridine as a ligand in acetonitrile at 80 °C in the presence of trifluoromethylating agent 8. In contrast, α-aryl-β-trifluoromethylamides bearing a quaternary stereocenter 20 were obtained with Cu2O as a catalyst when an aromatic ring was attached to the nitrogen atom (Scheme 15). Both transformations could be rationalized on the basis of a mechanism involving the trifluoromethylation of the activated alkene to give an alkyl radical intermediate 21 as shown in Scheme 16. Upon cyclization with the arylsulfonyl moiety, a spirobicyclic intermediate 22 was formed. Re-aromatization accompanied by desulfonylation delivered an amidyl radical 23 which could either undergo protonation to give the corresponding amides 20 or, alternatively, form a new C(sp2)–N bond in the ortho relative position to the original sulfonyl group explaining oxindoles 19. In both processes, a copper-catalyzed one-pot trifluoromethylation, 1,4-aryl migration and desulfonylation cascade seemed thus to be operating.

Scheme 15. Copper-catalyzed aryltrifluoromethylation–desulfonylation cascade on acrylamides 18.

Scheme 16. Mechanism of the copper-catalyzed aryltrifluoromethylation–desulfonylation cascade.

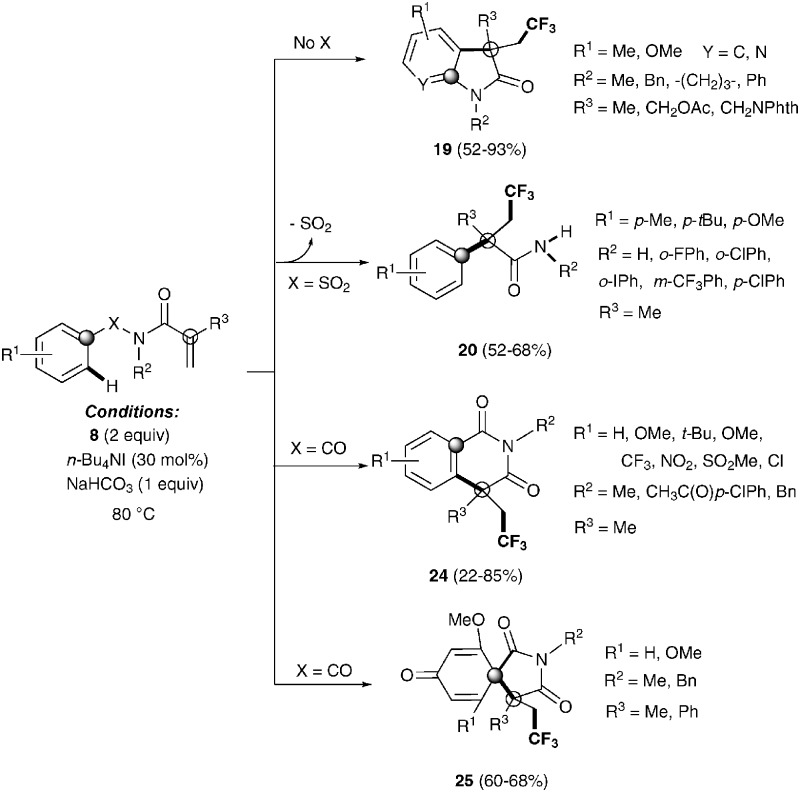

The same group also described the first example of a metal-free alkene aryltrifluoromethylation. 34 Tetrabutylammonium iodide could activate Togni reagent 8 forming highly active iodine(iii) species, which seem to easily release the CF3 group. Trifluoromethylated isoquinolinediones 24, oxindoles 19, spirobicycles 25 and α-aryl-β-trifluoromethylamides 20 could be obtained by this procedure with excellent yields in a highly regioselective fashion (Scheme 17). Preliminary mechanistic studies seemed to rule out a radical mechanism for these transformations. An alternative metal-free aryltrifluoromethylation of alkenes was also recently described using inexpensive TMSCF3, PhI(OAc)2 and KF as additives likely involving radical intermediates. 35

Scheme 17. Metal-free trifluoromethylation reaction of methacryloyl benzamides and α,β-unsaturated amides.

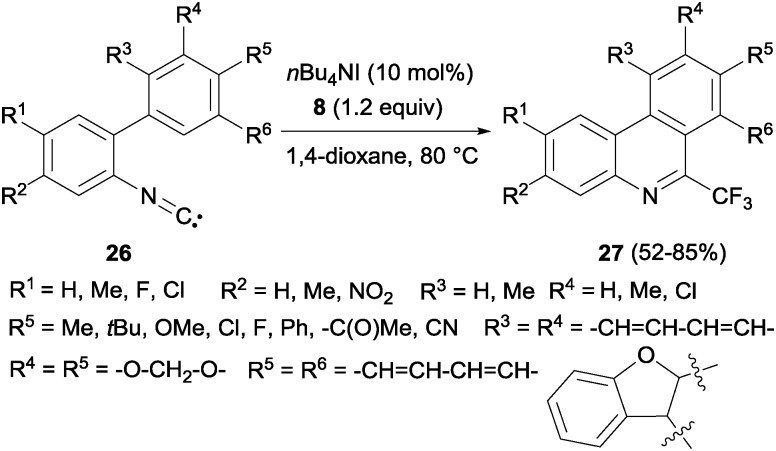

Interestingly, a metal-free synthesis of phenanthridines 27 from isonitriles 26 was previously described by Studer's group using tetrabutylammonium iodide as an activator of Togni reagent 8 in a radical process (Scheme 18). 36 A new phenyl ring is formed after trifluoromethylation reaction. Also Zhou's group described the synthesis of phenanthridines by oxidative cyclization of 2-isocyanobiphenyls with PhI(OAc)2 and CF3SiMe3. 37

Scheme 18. Metal-free synthesis of 6-trifluoromethyl-phenanthridines.

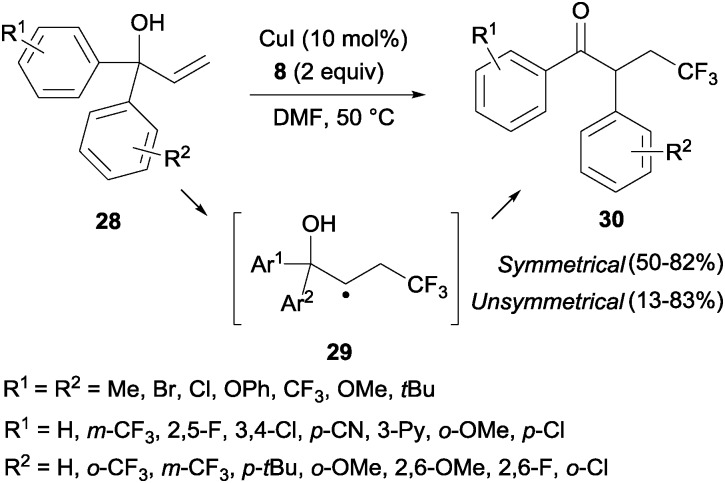

The trifluoromethylation of α,α-diaryl allylic alcohols 28 provided trifluoromethyl ketones 30 through a 1,2-aryl migration in intermediate 29 upon addition of a CF3 radical to the double bond (Scheme 19). 38 Aromatic rings bearing electron-withdrawing groups migrated preferentially over electron-rich aryl groups in line with the radical mechanism proposed for this transformation. Sodeoka's group showed that iron acetate in the presence of base (K2CO3) also led to the formation of substituted trifluoromethylated carbonyl compounds starting from diaryl allyl alcohols in very good yields. 39

Scheme 19. Copper-catalyzed trifluoromethylation and radical 1,2-aryl migration in α,α-diaryl allylic alcohols.

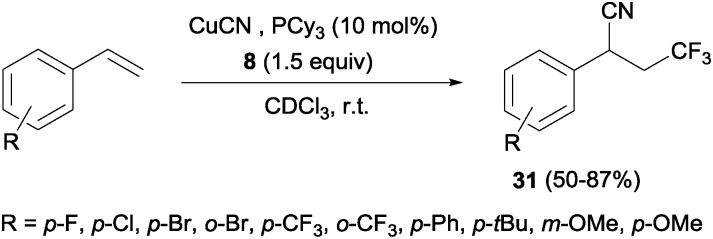

Other interesting example that combined alkene trifluoromethylation with the formation of a new C–C bond was described by Szabó's group. 40 Styrenes, in the presence of CuCN as the cyanide source and bulky phosphines or B2pin2 as additives, delivered cyanotrifluoromethylated aromatic compounds 31 in a highly regioselective manner in a one-pot trifluoromethylation/C–C bond formation (Scheme 20). This protocol was limited to styrenes with electron-withdrawing para and ortho substituents. However, this reaction was also described with aliphatic and ortho, meta and para-substituted aromatic substrates with good yields using Cu(OTf)2 as a catalyst, 8 as a trifluoromethylating agent and TMSCN as a cyanide source. 41

Scheme 20. Trifluoromethylation–cyanation of styrene derivatives.

3. Alkene trifluoromethylation and C–heteroatom bond formation

3.1. Alkene trifluoromethylation and C–O bond formation

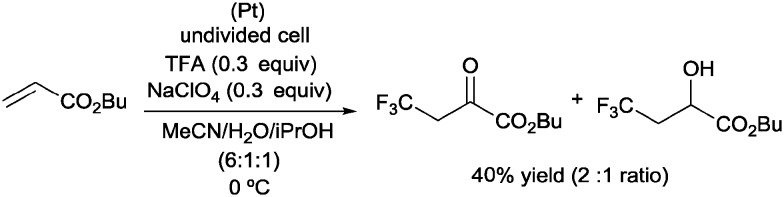

As discussed in Section 1, the electrooxidation of trifluoroacetic acid was an efficient way to generate CF3 radicals in situ. Thus, pioneering examples of alkene oxotrifluoromethylations were reported under these reaction conditions. In a representative example, the reaction of butyl acrylate, under controlled electrooxidation conditions, furnished 4,4,4-trifluoro-2-oxobutanoate and butyl 4,4,4-trifluoro-2-hydroxybutanoate in a 2 : 1 ratio and 40% overall yield (Scheme 21). 42

Scheme 21. Electrooxidative alkene oxotrifluoromethylation.

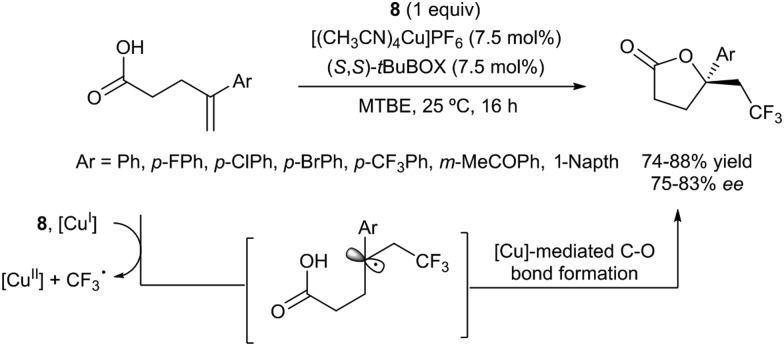

The first examples of oxotrifluoromethylation in unactivated alkenes were reported by Buchwald and co-workers in 2012. Based on the [Cu(MeCN)4PF6]/2,2′-biquinoline catalytic system and in the presence of Togni reagent 8, the intramolecular nucleophilic attack of various oxygenated species such as carboxylic acids, alcohols and phenols following trifluoromethyl addition to the double bond could be carried out. A broad array of functional groups including amides, epoxides, aryl bromides and β-lactones were compatible with the reaction conditions. 43 In addition, an enantioselective version of this transformation was described by the same group using (S,S)-tBuBOX as a chiral ligand for copper. 44 The mechanistic proposal involved a metal C–O bond formation via a carbon radical intermediate as shown in Scheme 22.

Scheme 22. Copper-catalyzed enantioselective oxotrifluoromethylation of unactivated olefins.

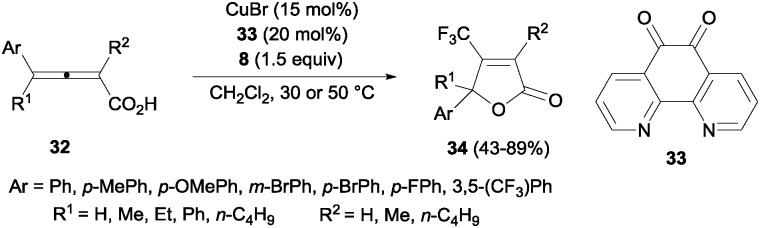

Trifluoromethyl-substituted isoxazolines could also be obtained by cyclization of oximes after C–CF3 bond formation using 20 mol% of CuCl and Togni's reagent. 45 A related protocol using CuBr and 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione 33 was described by Ma and co-workers for the efficient oxotrifluoromethylation of 2,3-allenoic acids 32. β-Trifluoromethylated butenolides 34 could be obtained in moderate to high yields (Scheme 23). 46

Scheme 23. Oxytrifluoromethylation of 2,3-allenoic acids.

The combination of copper salts and Togni reagent 8 was also successfully applied to the oxotrifluoromethylation of styrenes and arylalkynes as reported by Szabó and co-workers. 47 In these reactions, the 2-iodo benzoic acid generated upon transfer of the trifluoromethyl group from 8 reacted as an external nucleophile, delivering the corresponding trifluoromethylated vinyl or alkyl benzoates 35 and 36, respectively (Scheme 24). Direct formation of β-trifluoromethylstyrene derivatives from the corresponding styrene starting material was also achieved by Sodeoka's group under closely related reaction conditions upon addition of a Bronsted acid. 48 An oxotrifluoromethylation of enamides was also reported in the presence of the CuCl/Togni's reagent system in MeOH as a solvent. 49

Scheme 24. Oxotrifluoromethylation of styrene and aryl alkyne derivatives.

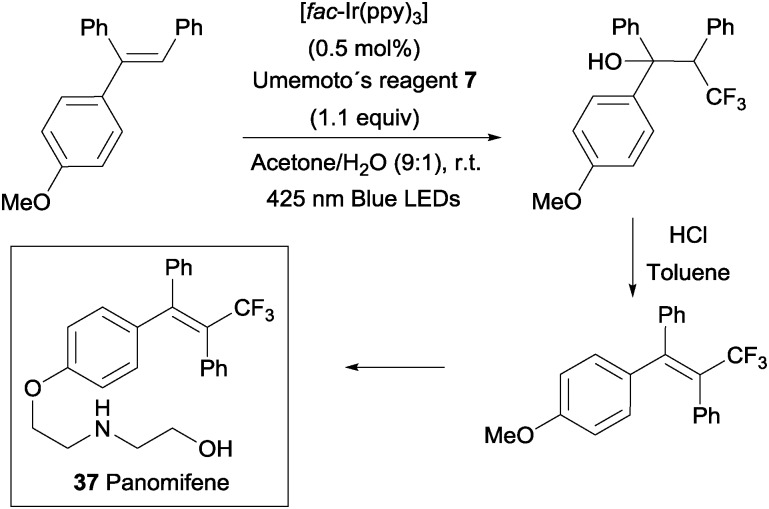

An intermolecular oxotrifluoromethylation of alkenes was also developed taking advantage of photoredox catalysis in a three component reaction using Umemoto's reagent 7 as a trifluoromethyl source. The reaction is highly regioselective and different O functionalities could be introduced in the styrene substrates. 50 This methodology was applied in the synthesis of panomifene 37, a compound with antiestrogenic activity used in the treatment of breast cancer (Scheme 25). 51,52

Scheme 25. Synthesis of panomifene.

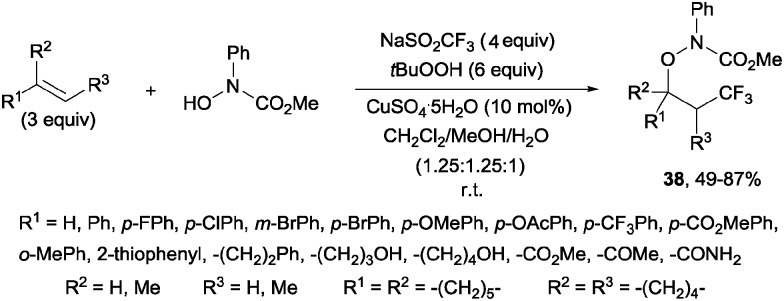

An additional three-component oxytrifluoromethylation of alkenes was reported by Qing and co-workers using hydroxyl amines, Langlois reagent (NaSO2CF3), t BuOOH and CuSO4·5H2O. This reaction is regioselective and a radical mechanism is proposed to explain the formation of the observed products 38 (Scheme 26). 53

Scheme 26. Oxytrifluoromethylation of alkenes using Langlois'reagent.

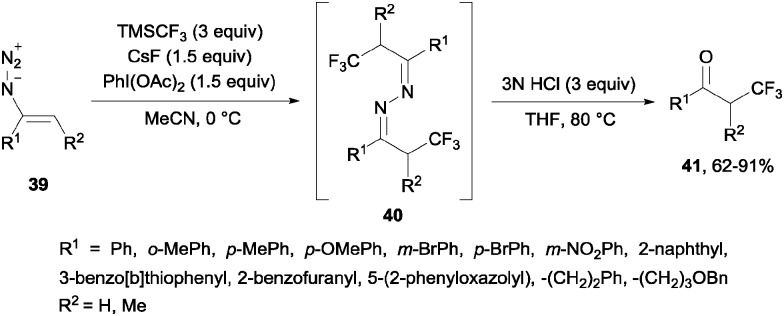

Alternatively, the oxidative trifluoromethylation of unactivated olefins with the system CF3SO2Na/AgNO3/K2S2O8 at room temperature provided a straightforward access to α-trifluoromethyl ketones in good yields with O2 as an ultimate oxygen source. 54 α-Trifluoromethylated ketones could also be obtained by reaction of styrenes and Umemoto's reagent 7 in the presence of Na2S2O4 or NaSO2CH2OH. Following the same principle as in the previous case, these reagents could reduce the sulfonium salt to generate a CF3 radical which reacted with styrene so that after oxidation with air, trifluoromethylated ketones were generated in moderate yields (21–39%). 55 α-Trifluoromethyl azines 40 could be obtained by radical trifluoromethylation of vinyl azides 39 using TMSCF3. These compounds could be transformed by simple methods into α-trifluoromethyl ketones 41, β-trifluoromethyl amines and 5-fluoropyrazoles (Scheme 27). 56

Scheme 27. Synthesis of α-trifluoromethyl ketones 41.

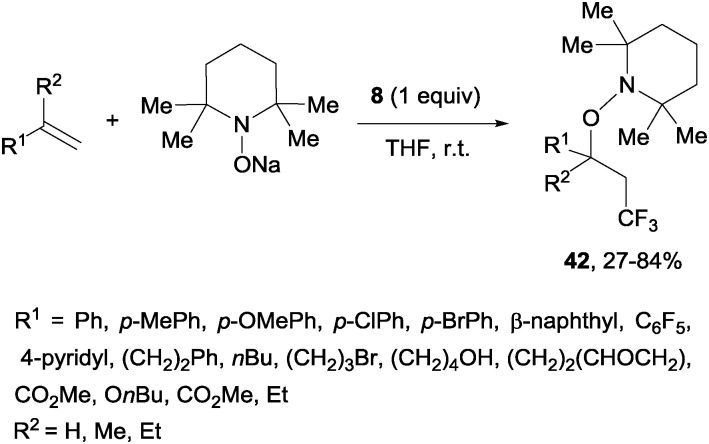

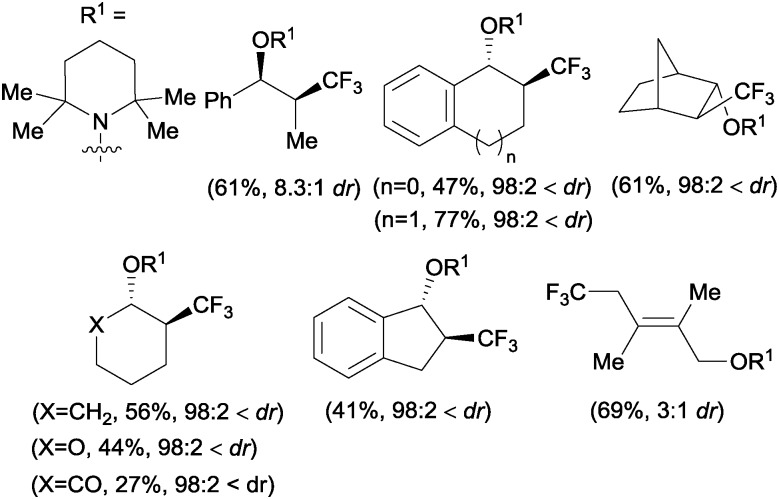

A novel metal-free trifluoromethylaminoxylation of alkenes was reported by Studer's group using TEMPONa. 57 This reagent was formed from TEMPO and sodium, whereas CF3 radicals could be released from Togni reagent 8 as shown in Scheme 28. The diastereoselectivity of the process was excellent when cyclic alkenes were used as starting materials (Scheme 29). The products (42) could be reduced with Zn/AcOH delivering synthetically useful β-trifluoromethylated secondary alcohols.

Scheme 28. Metal-free trifluoromethylaminoxylation of terminal alkenes.

Scheme 29. Diastereoselective trifluoromethylation of internal alkenes.

3.2. Alkene trifluoromethylation and C–N bond formation

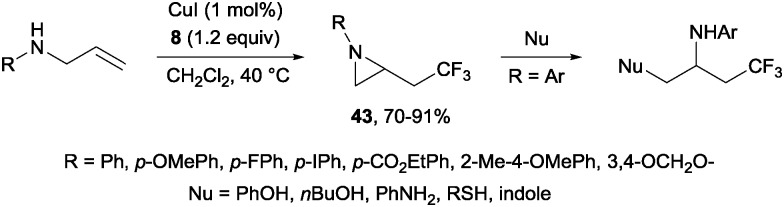

In contrast to the numerous studies dealing with the oxotrifluoromethylation of alkenes, the concomitant formation of C–N and C–CF3 bonds has been much less developed. Sodeoka and co-workers described one of the first examples of this type of transformations. Allyl amines react with CuI and Togni's reagent 8 to give aziridines 43 in high yields by trifluoromethylation and intramolecular C–N bond formation (Scheme 30). 58 One pot reactions including the ring-opening of the aziridine in the presence of various nucleophiles set the path for the efficient synthesis of β-trifluoromethylamines, which are important building blocks for bioactive compounds.

Scheme 30. Aminotrifluoromethylation of allylamines.

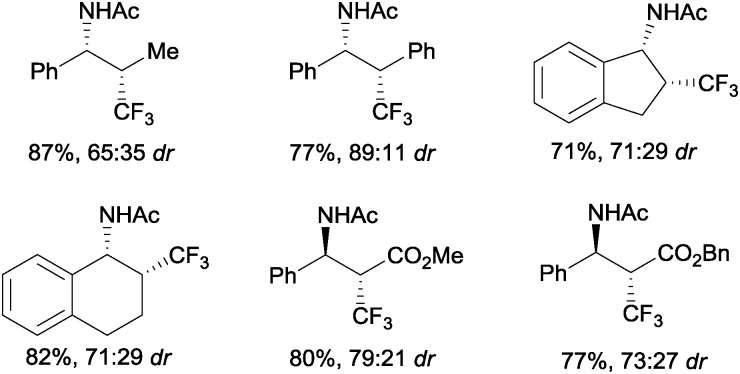

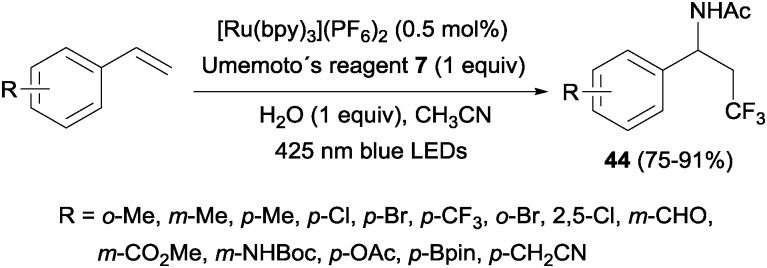

An intermolecular aminotrifluoromethylation of terminal alkenes by photoredox catalysis was also described using [Ru(bpy)3]2+ under visible light irradiation with Umemoto's reagent 7 as a precursor of CF3 radicals leading to α-trifluoromethylamines 44 (Scheme 31). Good levels of stereoselectivity were obtained in the reactions of internal alkenes (Scheme 32). 59

Scheme 31. Aminotrifluoromethylation of terminal alkenes.

Scheme 32. Products of aminotrifluoromethylation of internal alkenes.

3.3. Alkene trifluoromethylation and C–S bond formation

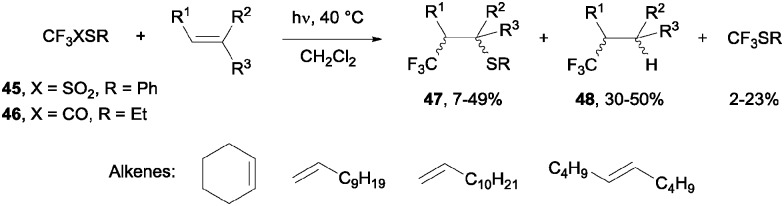

β-Sulfanyl-(trifluoromethyl)-alkanes 47 could be obtained by photolysis of trifluoromethanethiosulfonates 45 or trifluorothioacetates 46. The trifluoromethyl radicals generated under UV radiation could then be trapped by the double bond, although yields remained moderate and products 48, resulting from a formal hydrotrifluoromethylation reaction, could also be detected in the reaction media. This process is highly regioselective so that the product stemmed from the addition of the CF3 radical on the less hindered carbon of the alkene (Scheme 33). 60

Scheme 33. Photolysis of trifluoromethanethiosulfonate and trifluorothioacetate in the presence of alkenes.

3.4. Alkene trifluoromethylation and C–halogen bond formation

Formally, the one-pot trifluoromethylation and C–halogen bond formation across double bonds were first described in the 50's when olefin polymerizations were carried out in the presence of iodotrifluoromethane. 61 Thus, the reaction of iodotrifluoromethane with tetrafluoroethylene enabled the synthesis of short-chain tetrafluoroethylene polymers with general formula CF3–[CF2–CF2] n –I (n = 1–10).

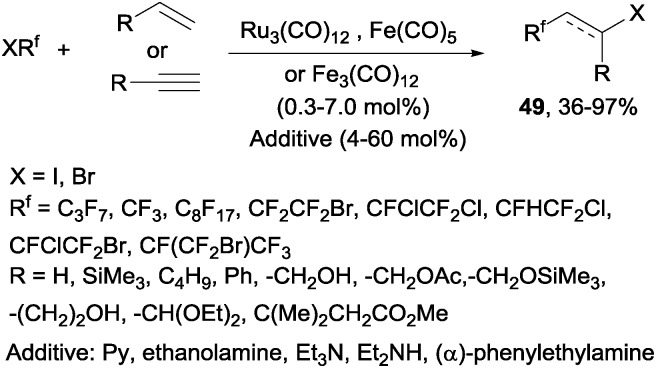

Decades later, the reaction of polyfluoroalkyl halides with alkenes and alkynes catalyzed by iron, cobalt and ruthenium complexes produced the corresponding addition products 49 in moderate to excellent yields (Scheme 34). 62 Other metals such as platinum, 63 nickel 63 or palladium 64,65 could also be used to catalyze this reaction.

Scheme 34. Reaction of polyfluoroalkyl halides with alkenes and alkynes.

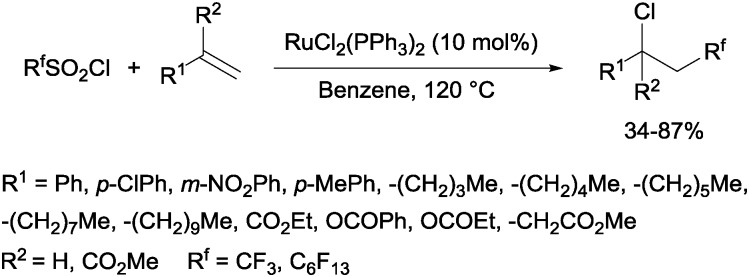

Trifluoromethanesulphonyl chloride 66 and perfluoroalkanesulphonyl chlorides 67 could also be incorporated into alkenes in a reaction catalyzed by a ruthenium(ii) complex as shown in Scheme 35.

Scheme 35. Reaction of perfluoroalkanesulphonyl chlorides with alkenes.

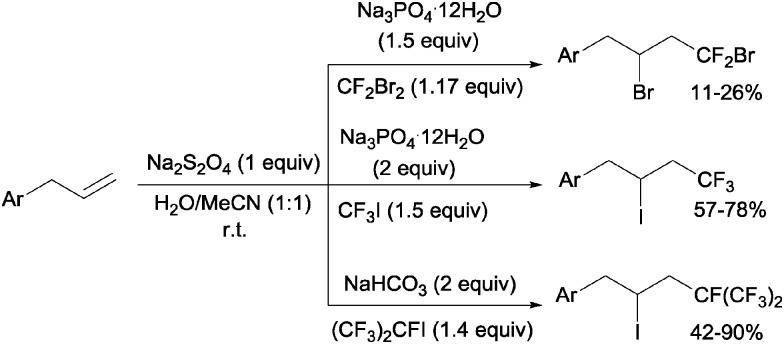

Addition of CF2Br2, CF3I and (CF3)CFI to allylbenzenes could be carried out by sodium dithionite in a H2O:MeCN mixture through a simple chain radical mechanism (Scheme 36). 68 The reaction of CF2Br2 and CF3I with allylbenzenes had to be performed in a closed system because of the volatility of the former whereas the addition of (CF3)2CFI was carried out in the presence of NaHCO3 as a HI scavenger.

Scheme 36. Sodium dithionite initiated addition of CF2Br2, CF3I and (CF3)2CFI to allylbenzenes.

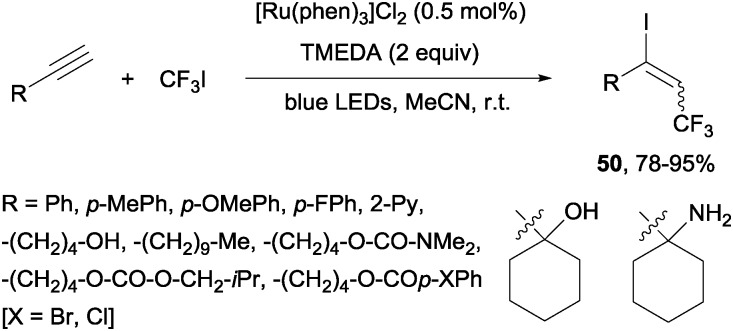

Recently, alkynes in the presence of [Ru(phen)3]Cl2 and TMEDA under visible-light irradiation produced trifluoromethylated alkenyl iodides 50 in an E-selective manner (Scheme 37). 69

Scheme 37. Iodotrifluoromethylation of alkynes.

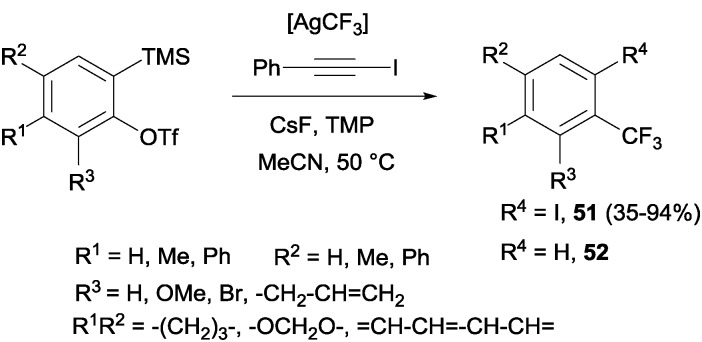

Trifluoromethylation and iodination of arynes were also described using AgCF3 (generated in situ by mixing TMSCF3 and AgF) in the presence of 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine, which accelerated the iodination and suppressed the undesired protonation yielding by-product 52 (Scheme 38). 70

Scheme 38. Iodotrifluoromethylation of arynes.

Conclusions

As a result of the growing interest in the efficient synthesis of fluorinated molecules, alkenes have aroused as highly valuable building blocks for the construction of C–CF3 bonds. In this review, we have aimed to show the latest progress in the incorporation of CF3 groups across C C π-systems: from the formal addition of HCF3 to the simultaneous formation of C–C/X and C–CF3 bonds to produce X–C–C–CF3 moieties, we have showcased the most synthetically useful methodologies and the corresponding mechanistic manifolds operating in this rapidly evolving field.

Acknowledgments

The European Research Council (ERC Starting grant agreement no. 307948) is kindly acknowledged for financial support.

Biographies

E. Merino

Estíbaliz Merino obtained her PhD degree from the Autónoma University (Madrid-Spain) under the supervision of Prof. Carmen Carreño. After a postdoctoral stay with Prof. Magnus Rueping at Goethe-Frankfurt and RWTH-Aachen Universities (Germany) in the field of organocatalysis, she worked with Prof. Avelino Corma at the Instituto de Tecnología Química (ITQ) (Valencia-Spain) and Prof. Félix Sánchez at Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Químicas (CSIC) (Madrid-Spain) in heterogeneous catalysis. At present, she is a research associate in Prof. Cristina Nevado's group at the University of Zürich. She is interested in the synthesis of natural products using catalysis tools.

C. Nevado

Cristina Nevado received her PhD from the Autónoma University (Madrid-Spain) working with Prof. Antonio M. Echavarren in late transition metal catalysis. After a post-doctoral stay in the group of Prof. Alois Fürstner at the Max-Planck-Institut für Kohlenforschung (Germany), she joined the University of Zürich as an Assistant Professor in May 2007. In 2011, Cristina was awarded the Chemical Society Reviews Emerging Investigator Award and the Thieme Chemistry Journal Award. In 2012 she received an ERC Junior Investigator grant and the Werner Prize of the Swiss Chemical Society becoming Full Professor in 2013. Rooted in the wide area of organic chemistry, her research program is focused on complex chemical synthesis and new organometallic reactions.

References

- Kirsch P., Modern Fluoroorganic Chemistry: Synthesis Reactivity Applications, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki T., Taguchi T. and Ojima I., Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, Great Britain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata N., Mizuta S., Kawai H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2008;19:2633–2644. [Google Scholar]

- Tomashenko O. A., Grushin V. V. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:4475–4521. doi: 10.1021/cr1004293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya T., Kamlet A. S., Ritter T. Nature. 2011;473:470–477. doi: 10.1038/nature10108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.-F., Neumann H., Beller M. Chem. – Asian J. 2012;7:1744–1754. doi: 10.1002/asia.201200211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y., Sanford M. S. Synlett. 2012:2005–2013. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1316988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:8950–8958. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Liu G. Synthesis. 2013:2919–2939. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Gu Z., Jiang X. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013;355:617–626. [Google Scholar]

- Muller N. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:263–265. [Google Scholar]

- Uneyama K., Watanabe S., Tokunaga Y., Kitagawa K., Sato Y. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1992;65:1976–1981. [Google Scholar]

- Uneyama K., Watanabe S. J. Org. Chem. 1990;55:3909–3912. [Google Scholar]

- Dan-oh Y., Uneyama K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1995;68:2993–2996. [Google Scholar]

- Tommasino J.-B., Brondex A., Médebielle M., Thomalla M., Langlois B. R., Billard T. Synlett. 2002:1697–1699. [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Omote M., Ando A., Kumadaki I. Org. Lett. 2004;6:4359–4361. doi: 10.1021/ol048134v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdbrink H., Peuser I., Gerling U. I. M., Lentz D., Koksch B., Czekelius C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:8583–8586. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26810h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Chu L., Qing F.-L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:2198–2202. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuta S., Verhoog S., Engle K. M., Khotavivattana T., O'Duill M., Wheelhouse K., Rassias G., Médebielle M., Gouverneur V. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:2505–2508. doi: 10.1021/ja401022x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilger D. J., Gesmundo N. J., Nicewicz D. A. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:3160–3165. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons A. T., Buchwald S. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:9120–9123. doi: 10.1002/anie.201104053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Ye Y., Zhang S., Feng J., Xu Y., Zhang Y., Wang J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:16410–16413. doi: 10.1021/ja207775a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Fu Y., Luo D.-F., Jiang Y.-Y., Xiao B., Liu Z.-J., Gong T.-J., Liu L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:15300–15303. doi: 10.1021/ja206330m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu R., Egami H., Hamashima Y., Sodeoka M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:4577–4580. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuta S., Galicia-López O., Engle K. M., Verhoog S., Wheelhouse K., Rassias G., Gouverneur V. Chem. – Eur. J. 2012;18:8583–8587. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu X., Wu T., Wang H.-y., Guo Y.-l., Liu G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:878–881. doi: 10.1021/ja210614y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egami H., Shimizu R., Sodeoka M. J. Fluorine Chem. 2013;152:51–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Klumphu P., Liang Y.-M., Lipshutz B. H. Chem. Commun. 2014;50:936–938. doi: 10.1039/c3cc48131j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q., Liu C., Peng P., Liu Z., Fu L., Huang J., Lei A. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2014;3:273–276. [Google Scholar]

- Egami H., Shimizu R., Kawamura S., Sodeoka M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:4000–4003. doi: 10.1002/anie.201210250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X., Sang R., Wang Q., Tang X.-Y., Shi M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013;19:16910–16915. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P., Yan X.-B., Tao T., Yang F., He T., Song X.-R., Liu X.-Y., Liang Y.-M. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013;19:14420–14424. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W., Casimiro M., Merino E., Nevado C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:14480–14483. doi: 10.1021/ja403954g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W., Casimiro M., Fuentes N., Merino E., Nevado C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:13086–13090. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Deng M., Zheng S.-C., Xiong Y.-P., Tan B., Liu X.-Y. Org. Lett. 2014;16:504–507. doi: 10.1021/ol403391v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Mück-Lichtenfeld C., Daniliuc C. G., Studer A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:10792–10795. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Dong X., Xiao T., Zhou L. Org. Lett. 2013;15:4846–4849. doi: 10.1021/ol4022589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Xiong F., Huang X., Xu L., Li P., Wu X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:6962–6966. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egami H., Shimizu R., Usui Y., Sodeoka M. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:7346–7348. doi: 10.1039/c3cc43936d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilchenko N. O., Janson P. G., Szabó K. J. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:11087–11091. doi: 10.1021/jo401831t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.-T., Li L.-H., Yang Y.-F., Zhou Z.-Z., Hua H.-L., Liu X.-Y., Liang Y.-M. Org. Lett. 2014;16:270–273. doi: 10.1021/ol403263c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y., Watanabe S., Uneyama K. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1993;66:1840–1843. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu R., Buchwald S. L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:12462–12465. doi: 10.1021/ja305840g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu R., Buchwald S. L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:12655–12658. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y.-T., Li L.-H., Yang Y.-F., Wang Y.-Q., Luo J.-Y., Liu X.-Y., Liang Y.-M. Chem. Commun. 2013;49:5687–5689. doi: 10.1039/c3cc42588f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q., Ma S. Chem. – Eur. J. 2013;19:13304–13308. doi: 10.1002/chem.201302169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson P. G., Ghoneim I., Ilchenko N. O., Szabó K. J. Org. Lett. 2012;14:2882–2885. doi: 10.1021/ol3011419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egami H., Shimizu R., Sodeoka M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012;53:5503–5506. [Google Scholar]

- Feng C., Loh T.-P. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:3458–3462. [Google Scholar]

- Yasu Y., Koike T., Akita M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:9567–9571. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Németh G., Kapiller-Dezsöfi R., Lax G., Simig G. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:12821–12830. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Shimizu M., Hiyama T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:879–882. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X.-Y., Qing F.-L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:14177–14180. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deb A., Manna S., Modak A., Patra T., Maity S., Maiti D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:9747–9750. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.-P., Wang Z.-L., Chen Q.-Y., Zhang C.-T., Gu Y.-C., Xiao J.-C. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:6632–6634. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11765c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.-F., Lonca G. H., Chiba S. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:1067–1071. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Studer A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:8221–8224. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egami H., Kawamura S., Miyazaki A., Sodeoka M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:7841–7844. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasu Y., Koike T., Akita M. Org. Lett. 2013;15:2136–2139. doi: 10.1021/ol4006272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billard T., Roques N., Langlois B. R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:3069–3072. [Google Scholar]

- Haszeldine R. N. J. Chem. Soc. 1949:2856–2861. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchikami T., Ojima I. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:303–306. [Google Scholar]

- Von Werner K. J. Fluorine Chem. 1985;28:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara T., Kuroboshi M., Okada Y. Chem. Lett. 1986:1895–1896. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q.-Y., Yang Z.-Y., Zhao C.-X., Qiu Z.-M. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1988:563–567. [Google Scholar]

- Kamigata N., Fukushima T., Yoshida M. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1989:1559–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Kamigata N., Fukushima T., Terakawa Y., Yoshida M., Sawada H. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1991:627–633. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatowska J., Dmowski W. J. Fluorine Chem. 2007;128:997–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal N., Jung J., Park S., Cho E. J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:539–542. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y., Zhang L., Zhao Y., Ni C., Zhao J., Hu J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:2955–2958. doi: 10.1021/ja312711c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]