Abstract

Large conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels represent an important pathway for the outward flux of K+ ions from the intracellular compartment in response to membrane depolarization, and/or an elevation in cytosolic free [Ca2+]. They are functionally expressed in a range of mammalian tissues (e.g., nerve and smooth muscles), where they can either enhance or dampen membrane excitability. The diversity of BK channel activity results from the considerable alternative mRNA splicing and post-translational modification (e.g., phosphorylation) of key domains within the pore-forming α subunit of the channel complex. Most of these modifications are regulated by distinct upstream cell signaling pathways that influence the structure and/or gating properties of the holo-channel and ultimately, cellular function. The channel complex may also contain auxiliary subunits that further affect channel gating and behavior, often in a tissue-specific manner. Recent studies in human and animal models have provided strong evidence that abnormal BK channel expression/function contributes to a range of pathologies in nerve and smooth muscle. By targeting the upstream regulatory events modulating BK channel behavior, it may be possible to therapeutically intervene and alter BK channel expression/function in a beneficial manner.

Keywords: calcium-activated K+ channel, β subunit, phosphorylation, modulation, smooth muscle, neuron, contractility

Introduction: BK channel distribution and architecture

BK channels, also called MaxiK/Slo1/KCa1.1 channels, are a class of K+ ion channels that undergo extensive pre- and post-translational modification. BK channel α subunits are encoded by the KCNMA1 gene, also known as SLO, and are ubiquitously expressed throughout mammalian tissues (e.g., neurons, smooth and skeletal muscles, exocrine cells). BK channels are assembled and strategically positioned on membrane surfaces, including the plasma membrane (Latorre et al., 1989), mitochondria and nucleus (Singh et al., 2012). Functional BK channels are multimeric structures composed of four similar pore-forming α subunits (Shen et al., 1994) and up to four regulatory β subunits can co-assemble with the tetrameric α subunit complex. The synergistic activation of BK channels by Ca2+ ions and depolarization causes a substantial K+ current that exhibits a large or “big” single channel conductance (i.e., up to 250 pS under symmetric K+ conditions). Activation of this formidable ionic current serves to drive membrane potential in the negative direction.

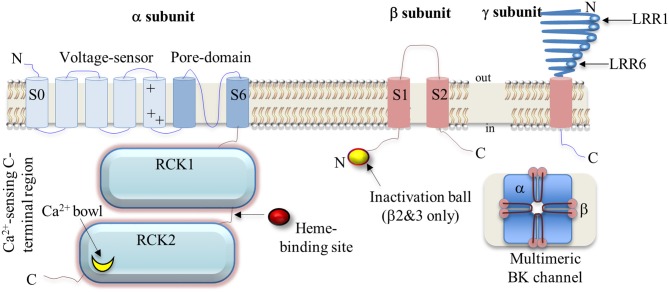

The transmembrane portion of the BK channel α subunit structure is thought to largely resemble that of voltage-gated K+ (Kv) channel subunits in terms of voltage-sensing and pore-forming domains. Notably, BKα subunits contain an additional transmembrane segment, termed S0, resulting in an extracellular N-terminus. Specialized charged residues are present within the transmembrane segments S2–S4 of the BKα subunit that contribute to its voltage-sensing properties. While topologically similar to their Kv channel counterparts, BK channels display weaker or less sensitive voltage-dependent activation (i.e., the ionic conductance-voltage relation is less steep), due to an altered distribution of voltage-sensing residues within the S2–S4 segments (Ma et al., 2006). Mechanistically, membrane depolarization drives conformational re-arrangements in the voltage sensor domains, resulting in an upward twisting of the S4 segment relative to the pore domain; these conformational movements are reversed upon repolarization (Hoshi et al., 2013).

The C-terminal domain of the BKα subunit contains a considerable range of specialized structures that regulate channel function. These include several binding sites for divalent cations (i.e., Ca2+ and Mg2+) and regions that undergo dynamic post-translational modification such as phosphorylation. Each mammalian BKα subunit contains two “regulators of K+ conductance” (RCK) domains, arranged in tandem along the C-terminus; in the tetrameric channel complex, these RCK domains co-assemble to form an octomeric gating ring structure in the cytosol (Yuan et al., 2010). The RCK domains also have Ca2+-binding regions and are crucial in conferring the channel's Ca2+ ion sensing properties (Cui et al., 2009). Ca2+ ions bind to these specialized regions within the BKα C-terminus, leading to a structural expansion of the intracellular region of the ion conduction pathway that facilitates gating and K+ efflux (Yuan et al., 2012; Hoshi et al., 2013).

Genetic diversity and splice variants

Unlike the Kv channel superfamily, which uses different genes to increase its genetic diversity, BK channels derive functional diversity through the alternative post-transcriptional splicing of mRNA derived from the single KCNMA1 gene encoding the BKα subunit (Shipston, 2001). Up to ten distinct splice sites have been described in KCNMA1 (Poulsen et al., 2009), leading to the generation of BKα subunits with different phenotypes and various functional roles, including altered sensitivity to Ca2+ and/or voltage (Shipston, 2001; Johnson et al., 2011), responses to phosphorylation (Tian et al., 2001), signaling cascades (Schubert and Nelson, 2001; Tian et al., 2001, 2004), membrane expression regulation (Alioua et al., 2008; Ahrendt et al., 2014), trafficking and lipidation (Toro et al., 2006; Zarei et al., 2007; Shipston, 2014). The impressive range of phenotypic products that can result from differential splicing of the KCNMA1 gene product contributes to diversity of BK channel function between tissues, cells and intracellular compartments.

BK channel auxiliary subunits

BK channels can co-assemble with modulatory auxiliary subunits BKβ 1-4 (Knaus et al., 1994a; Tanaka et al., 1997; Brenner et al., 2000a; Uebele et al., 2000), as well as a newly defined family of leucine-rich repeat containing subunits (LRRCs), referred to as γ subunits (Yan and Aldrich, 2010, 2012). Both BKβ and γ subunits contain sizeable extracellular regions and it is thought that these regions physically interact with the membrane-spanning domains of the BKα subunit. In particular, BKβ subunits appear to interact mainly with the N-terminal S0–S2 segments of the pore-forming BKα subunit (Morrow et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2008; Morera et al., 2012), thereby regulating channel opening through allosteric effects on the intramolecular processes underlying Ca2+ and/or voltage-dependent activation. As these auxiliary subunits are expressed in a tissue-specific manner, they confer distinct functional consequences by impacting BK channel kinetics and gating behavior. For instance, BKβ 1 subunits are typically expressed in smooth muscle, whereas BKβ 4 are expressed in neural tissue. BKβ subunits 1, 2 and 4 are reported to stabilize the channel's voltage sensor domains in the active conformation (Contreras et al., 2012), thereby enhancing channel activity, In contrast, BKβ 2 and β 3 subunits confer BK channel inactivation via an N-terminal “inactivation ball” (Wallner et al., 1999; Brenner et al., 2000a; Uebele et al., 2000) (Figure 1), which will limit K+ efflux and membrane hyperpolarization. To date, two functionally-distinct BKβ 2 splice variants (BKβ 2a−b) have been described in mammals, although BKβ 2b does not appear to inactivate the channel complex (Ohya et al., 2010). Similarly, four functionally-distinct BKβ 3 splice variants (BKβ 3a−d) are known, with splice variants A-C conferring partial inactivation of BK channel current (Uebele et al., 2000). BKβ 4 subunits are the most distantly-related of the β subunits in terms of sequence similarity and produce mixed effects on BK channel gating, depending on the local Ca2+ concentration. At low Ca2+ concentrations, BKβ 4 appears to decrease channel activation, but at high Ca2+ concentrations, activation is enhanced (Brenner et al., 2000a; Wang et al., 2006).

Figure 1.

A schematic illustration of BK channel α, β and γ subunit architecture with major structures defined. Abbreviations: N, amino-terminus; C, carboxy-terminus; LRR, leucine-rich repeat; S, transmembrane segment; RCK, regulator of K+ conductance.

The molecular mechanisms by which γ-subunits interact with and influence BK channel gating and kinetics are currently an area of active investigation. All four known LRRC proteins (i.e., LRRC26, 38, 52, and 55) have been reported to enhance voltage-dependent activation of BK channels (Yan and Aldrich, 2010, 2012), with LRRC26 producing an impressive shift of up to −150 mV.

Role of BK channels in smooth muscle function and disease

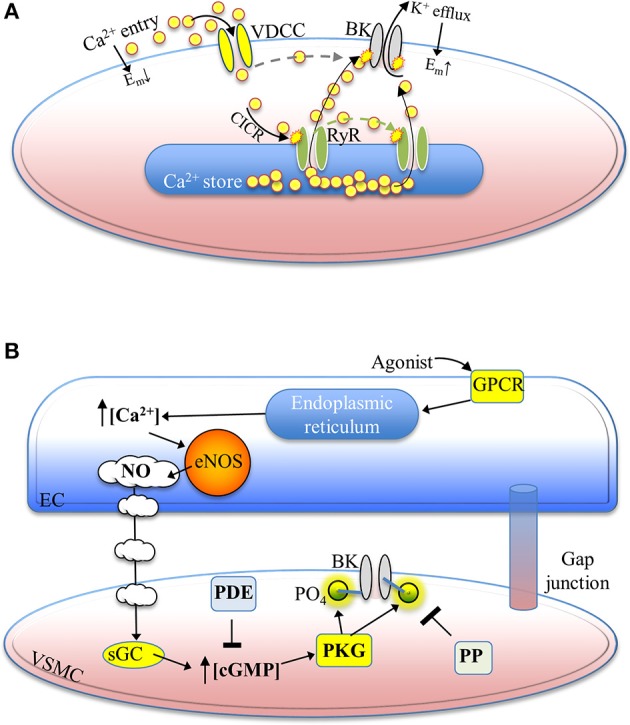

Phasic smooth muscles, such as those lining the urinary bladder, urethra and ureters, undergo action potential (AP) events, with rapid depolarization-repolarization fluctuations. APs cause a significant global increase in intracellular [Ca2+] and BK channels are largely responsible for the rapid down-stroke (repolarization) phase (Burdyga and Wray, 2005; Thorneloe and Nelson, 2005; Kyle et al., 2013b). In contrast, tonic smooth muscles, such as those found throughout vascular tissue and much of the gastrointestinal tract and airways, regulate lower magnitude changes in membrane potential by principally responding to localized elevations in intracellular [Ca2+] mediated by ryanodine receptors (RyRs) (Figure 2). The dynamic post-translational “tuning” of BK channels permits considerable diversity in the biophysical properties of the current.

Figure 2.

A summary of select physiological mechanisms leading to BK channel activation and reversible phosphorylation-mediated enhancement. (A) Ca2+ –dependent activation of BK channels hyperpolarizes the membrane potential. Depolarization of the membrane potential activates voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels, leading to Ca2+ entry and Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from nearby ryanodine receptors. Released Ca2+ promotes BK channel activation, which drives the membrane potential in the negative (hyperpolarized) direction. Ca2+ influx via VDCCs may also contribute directly to BK channel activation (dotted line) as a result of the spatial proximity of these two channels within membrane nano/micro-domains. (B) Mechanisms underlying the generation of nitric oxide from an endothelial cell, with the NO/cGMP/PKG-mediated phosphorylation of a BK channel illustrated in an adjacent vascular smooth muscle cell. Nitric oxide release from endothelial cells binds to soluble guanylyl cyclase in smooth muscle cells, resulting in elevated intracellular cGMP concentrations. PKG is then activated and phosphorylates the BKα subunit. Phosphodiesterase activity lowers intracellular cGMP and protein phosphatase activity removes the regulatory phosphate from Ser/Thr residues of the BK channel protein. Abbreviations: VDCC, voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel; BK, BK channel; Em, membrane potential; CICR, Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release; RyR, ryanodine receptor; GPCR, GTP-binding protein-coupled receptor; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; EC, endothelial cell; sGC, soluble guanylyl cyclase; PDE, phosphodiesterase; PO4, phosphate group; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; PKG, protein kinase G; PP, protein phosphatase; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

In common with many other tetrameric K+ channels in smooth muscles, the amplitude of K+ current carried through BK channels in smooth muscles can be dynamically regulated by post-translational modifications to the channel complex, including the reversible phosphorylation of the pore-forming BKα subunit by a number of protein kinases, as described below. Almost all phosphorylation sites are conserved in mammalian BK channel splice variants.

Many tissues have distinct macromolecular signaling complexes underlying the function of ion channels. Smooth muscles, for instance, generally have closely-associated RyRs, which periodically release Ca2+ and cause local elevations in [Ca2+]i (i.e., 10–20 μM) (Pérez et al., 1999; ZhuGe et al., 2002) near BK channels positioned on the plasma membrane, which is sufficient to significantly raise the Po and efflux K+ (Figure 2). The RyRs themselves are often close to Ca2+ influx pathways, for instance voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, or in proximity to IP3 receptors (Ohi et al., 2001).

The primary role of BK channels in vascular smooth muscle (VSM) is to repolarize/hyperpolarize the cell membrane potential in the face of chronic depolarizing stimuli, thereby reducing contractile activity. It is now well-recognized that enhancement of BK channel current in VSM via phosphorylation is principally-regulated by nitric oxide (NO)/cGMP/PKG signaling (Feil et al., 2003) (see Section BK Channel Modulation via Protein Phosphorylation below). NO is a gaseous second messenger synthesized mainly by the adjacent endothelial cell layer lining the lumen of all blood vessels (Fleming and Busse, 2003). Therefore, BK channel activity is considered to be closely linked with endothelial cell activity. Therapeutically, NO and synthetic NO donors are used to treat a range of vascular disorders, including angina pectoris and hypertension (Wimalawansa, 2008).

In addition to the urinary tract and VSM, BK channels are also important regulators in mediating the proper function of various other smooth muscles, including those found in the gastrointestinal tract, airway, and uterus. Their function, however, varies between cell types and layers, and generally is dependent on the associated macromolecular signaling complex. In the colon, for instance, BK channels contribute to setting the resting membrane potential in longitudinal smooth muscle, whereas in the circular layer, they limit excitatory responses (Sanders, 2008).

In VSM, a single amino acid polymorphism in the BKβ 1 subunit (i.e., E65K) is reported to have a gain-of-function effect on BKs channel activation and has been associated with lower systolic and diastolic blood pressures and a decreased prevalence of diabetic hypertension in humans (Fernández-Fernández et al., 2004; Nielsen et al., 2008). In contrast, BKβ 1 subunit expression is decreased in some forms of genetic hypertension (Amberg and Santana, 2003). Moreover, a point mutation (R140W) in the BKβ 1 subunit that modestly impairs channel opening has been linked with asthma severity in African-American males (Seibold et al., 2008). Provocative data from Jaggar and colleagues further suggest that the majority of BKβ 1 subunits reside within the cell interior and assemble with α subunits at the cell surface in a dynamic fashion (Leo et al., 2014). NO signaling appears to promote the forward trafficking of internal BKβ 1 subunits to the cell membrane, where they co-associate with BKα subunits to enhance channel activation. The authors suggest that auxiliary BKβ 1 subunits undergo selective endocytosis from the plasma membrane, followed by re-insertion in response to a vasodilatory stimulus, such as NO. These data imply that native BK channels in VSM may not always contain a full complement of β 1 subunits (i.e., the ratio of β 1 to α subunits in a single channel complex is <1), as described in rat cremaster artery (Yang et al., 2009), and that the subunit stoichiometry of these channels is not permanent. Dynamic regulation of BK channel subunit co-assembly and interaction at the plasma membrane may thus represent a novel paradigm for the modulation of ion channel activity.

Many research groups have reported that BK channel activity is upregulated during hypertension, and its contribution is apparently enhanced compared to normotensive animals (for review, see Joseph et al., 2013). It should be noted, however, that downregulation of BK channel activity has also been reported during hypertension (Amberg et al., 2003; Amberg and Santana, 2003; Nieves-Cintrón et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2013). Investigators have speculated that this decrease may be due to reduced BKβ 1 subunit expression/coupling, which would dampen the Ca2+ sensitivity of BK channel activation. Several research groups have reported that BK current density is positively-correlated to blood pressure in hypertensive animals (Rusch et al., 1992; England et al., 1993; Rusch and Runnells, 1994; Liu et al., 1998). Aortic smooth muscle isolated from rats with renal hypertension, spontaneously-hypertensive rats (SHR) and stroke-prone SHR (Rusch et al., 1992; England et al., 1993; Liu et al., 1998) exhibits significantly-upregulated BK channel activity, likely as a compensatory response. Collectively, these studies indicate that the expression and function of BK channels in the vasculature involves complex expression and signaling pathways, and may vary between cells, tissues, vascular beds and pathophysiological profiles.

BK channels are densely-expressed in mammalian bladder tissues (~20 channels per square micrometer) (Ohi et al., 2001) with BKβ 1 auxiliary subunits. BKα subunit knockout mice have demonstrated bladder dysfunction and exhibit a depolarized resting membrane potential in isolated bladder smooth muscle cells and intact tissues, indicating a role for BK channels in setting the membrane potential (Sprossmann et al., 2009). Inhibition of BK channel current with iberiotoxin in the bladders of healthy mice led to similar effects (Heppner et al., 1997; Hristov et al., 2011). BKβ 1-knockout mice similarly display overactive bladder symptoms, and a significant decrease in BK channel activity (Petkov et al., 2001). Intriguingly, bladder smooth muscle tissue taken from patients with neurogenic bladder over-activity exhibit little to no response to BK channel inhibition by iberiotoxin, or the channel agonist NS1619, indicating severe BK channel dysfunction (Oger et al., 2010). Macroscopic current recordings from these tissues demonstrated a significantly lower BK channel current density that mirrors that reported for experimentally-induced partial urethral obstruction in rats (Aydin et al., 2012). Patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia experiencing overactive bladder symptoms also demonstrate a parallel reduction in BK channel expression (Chang et al., 2010). Overexpression of BK channel protein in rats with experimentally-induced partial urethral obstruction proved to be an effective treatment for the existing overactive bladder activity (Christ and Hodges, 2006). These data collectively indicate that BK channels are important regulators of bladder smooth muscle excitability, and a potential target for therapeutic intervention for overactive bladder conditions.

Role of BK channels in neuronal function/dysfunction

BK channels are abundantly expressed in both central and peripheral neurons, with prominent expression reported in both the cell body and pre-synaptic terminals (Faber and Sah, 2003). Functionally, these channels are key regulators of neuronal excitability, as channel opening will reduce action potential (AP) amplitude and duration, increase the magnitude of the fast after-hyperpolarization (fAHP) immediately following repolarization and limit the frequency of AP burst firing (Bielefeldt and Jackson, 1993; Faber and Sah, 2003; Gu et al., 2007; Haghdoost-Yazdi et al., 2008). At the pre-synaptic nerve terminal, localized BK channel activity can modulate both the amplitude and duration of depolarization-evoked Ca2+ entry as a result of the rapid repolarization and deactivation of voltage-gated Cav 2.1 (i.e., P/Q-type) and 2.2 (N-type) Ca2+ channels (Robitaille and Charlton, 1992; Issa and Hudspeth, 1994; Marrion and Tavalin, 1998; Fakler and Adelman, 2008). Reduced Ca2+ influx will limit vesicle fusion at active zones, leading to decreased neurotransmitter release (Roberts et al., 1990; Hu et al., 2001; Raffaelli et al., 2004).

Dissecting the functional roles of BK channels in the nervous system has been greatly aided by the availability of highly selective toxins (i.e., iberiotoxin) (Kaczorowski and Garcia, 1999) and small molecule inhibitors (e.g., penitrem A, paxilline, lolitrem B) (Knaus et al., 1994b; Imlach et al., 2008; Nardi and Olesen, 2008), along with the generation of genetically-engineered mice lacking either BKα or β subunits (Brenner et al., 2000b, 2005; Plüger et al., 2001; Meredith et al., 2004; Sausbier et al., 2004). Such strategies have revealed that the loss of neuronal BK current, either acutely or chronically, increases membrane excitability by decreasing the magnitude of the fAHP. Reducing the fAHP facilitates more rapid membrane depolarization in response to a tonic stimulus, leading to higher frequency AP firing. Such alterations in neuronal activity are typically associated with neurological disorders in the CNS, including tremor and ataxia (Sausbier et al., 2004; Brenner et al., 2005; Imlach et al., 2008). Interestingly, a point mutation in the RCK1 domain of the BKα subunit (i.e., D434G) identified in a subset of epileptic patients has been shown to increase neuronal BK channel activity by enhancing Ca2+-dependent channel gating (Du et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2010). Functionally, increasing BK activity and the associated fAHP may augment membrane excitability in the soma by enhancing the recovery rate of fast Na+ currents from voltage-dependent inactivation and reducing the absolute refractory period of neuronal firing.

In the CNS of mice and humans, genetic knockout or mutational disruption of the molecular chaperone cysteine string protein (CSPα) is linked with early onset neurodegeneration (Fernandez-Chacon et al., 2004; Donnelier and Braun, 2014), and interestingly, these conditions are associated with a significant up-regulation of BK channel expression in mouse brain and cultured neurons (Kyle et al., 2013a; Ahrendt et al., 2014). Although the mechanistic link between increased BK expression/activity and neurodegeneration remains undefined, it is hypothesized that increased BK current density in pre-synaptic terminals and/or the soma may lead to disrupted synaptic membrane excitability and neurotransmitter release. As described below, elevated BK channel expression in the CNS is closely linked with epilepsy, strongly suggesting that increased BK current density can lead to neurological disorders and possibly synaptic dysfunction/degeneration.

Post-translational modification

Heteromeric BK channel complexes are the subject of extensive post-translational modifications, which can significantly alter channel behavior. Some modifications are highly-complex and require prior upstream modification(s) to the channel subunits.

BK channel modulation via protein phosphorylation

Perhaps the most studied enzymatically-driven modification of BK channels is the addition of phosphate (PO3−4) groups to functionally-important residues (Ser/Thr/Tyr) present within the channel's pore-forming α subunit. These reactions are catalyzed by select protein kinases and are reversed by the actions of protein phosphatases that dephosphorylate these sites following removal of the stimulus. Phosphorylation can be either stimulatory or inhibitory with respect to the open probability of the channel and can depend on several variables (see below).

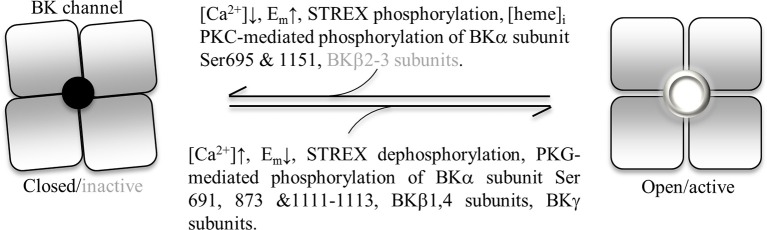

Regulation of BK channel activity in smooth muscles by phosphorylation-dependent signaling pathways is well documented (Schubert and Nelson, 2001) and the main modifying enzymes include cAMP- and cGMP-dependent protein kinases (i.e., PKA and PKG, respectively), protein kinase C (Zhou et al., 2010) along with c-Src tyrosine kinase (Davis et al., 2001). Biochemically, PKA is comprised of 2 catalytic and 2 regulatory subunits and kinase activation occurs in response to the direct binding of the second messenger cAMP to the regulatory subunits (Taylor et al., 1990). Cyclic AMP synthesis occurs following stimulation of adenylyl cyclase by hormones (e.g., adenosine, β-adrenergic agonists, PGI2, PGE2, etc.) or direct activators (e.g., forskolin). In the case of PKG activation, synthesis of cGMP can occur via a soluble or a membrane-bound form of guanylyl cyclase (Münzel et al., 2003); the former is typically activated by NO and the latter by natriuretic peptides acting on the cell surface receptors NPR-A and NPR-B. Structurally, PKG exists as a homodimer in which each monomer consists of a regulatory and catalytic domain linked in a single polypeptide chain (Francis et al., 2010); holo-PKG thus closely resembles the overall structure of PKA. Generally, PKA and PKG-mediated phosphorylation leads to BK channel enhancement, whereas PKC leads to channel inhibition. It should be stressed, however, that these regulatory effects on BK channel activity depend upon contextual phosphorylation/modification at multiple sites (Zhou et al., 2010, 2012; Kyle et al., 2013c), and may be further influenced by the constitutive phosphorylation status of the channel complex (see below). Selective blockade of the phosphodiesterase enzymes responsible for cGMP metabolism by pharmacologic agents such as sildenafil will prolong cGMP effects in smooth muscle and this process has been exploited therapeutically to treat erectile dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension (Francis et al., 2010). For a comprehensive overview of early studies describing BK channel regulation by kinase-associated pathways, see Schubert and Nelson (2001).

Using a multi-faceted strategy involving protein biochemistry, site-directed mutagenesis and patch clamp recordings, our group has recently reported that NO/cGMP/PKG signaling in VSM cells leads to the modification of three distinct Ser residues in the BKα C-terminus (i.e., Ser 691, 873 and 1111–1113), which directly correlate with enhancement of channel activity (Kyle et al., 2013c). Not unexpectedly, one of these sites (i.e., Ser873) is also important for PKA-mediated enhancement of BK activity (Nara et al., 1998). The regulatory phosphorylation status of BK channels also appears to differ developmentally, as BK channels in fetal arteries display more enhanced activity compared with channels from adult VSM (Lin et al., 2005, 2006). Augmentation of BK channel activity by NO/cGMP/PKG signaling is readily reversible and this is largely due to dephosphorylation via Ser/Thr protein phosphatases. Several studies have described involvement of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A in the regulation of BK channel activity, based mainly on the selective actions of inhibitors, such as okadaic acid (Zhou et al., 1996, 2010; Sansom et al., 1997).

Activation of PKC is reported to inhibit BK channel activity in VSM via the putative phosphorylation of Ser695 and Ser1151, and these modifications also appear to interfere with the stimulatory effects mediated by PKA and PKG (Zhou et al., 2010). Interestingly, this PKC-mediated inhibition of channel activity is absent in STREX-containing BKα splice variants (Zhou et al., 2012) (see below).

Similar to VSM, neuronal BK channel activity can be enhanced in response to regulatory phosphorylation of the pore-forming BKα subunit by both PKA and PKG, which can be reversed by the actions of Ser/Thr phosphatases 1 and 2A (Reinhart et al., 1991; Reinhart and Levitan, 1995; Sansom et al., 1997; Tian et al., 1998). Interestingly, proteomic analyses of rat brain BK channels isolated under basal conditions has identified ~30 Ser and Thr residues that appear to be constitutively phosphorylated in vivo, with 23 of these modified residues located within the channel's C-terminus (Yan et al., 2008). Such observations suggest that constitutive phosphorylation may help stabilize BK channel tertiary structure and/or create binding sites for interacting proteins. The various protein kinases responsible for these in vivo modifications are presently unknown, as is the extent to which channels from other tissues or expressed heterologously exhibit constitutive phosphorylation. Our recent data describing a role for multiple phosphorylation sites to support cGMP-dependent augmentation of BK channel activity in VSM cells (Kyle et al., 2013c) promote the idea that individual phospho-Ser/Thr residues act synergistically to enhance BK channel activity.

In neurons and neuroendocrine cells (e.g., pituitary, adrenal gland) and more recently in VSM (Nourian et al., 2014), a portion of BK channels identified by qRT-PCR contain the STREX splicing insert, a 59 amino acid insert present at splice site C2 within the C-terminus (Xie and McCobb, 1998; Shipston, 2001). In response to cAMP/PKA signaling, a Ser residue within the STREX insert can undergo phosphorylation, which has been shown to decrease BK channel activity (Tian et al., 2001). Functionally, such a change would be expected to enhance membrane excitability in neuroendocrine cells and promote exocytosis. Interestingly, phosphorylation of the STREX domain also appears to override the positive gating effects mediated by PKA-induced phosphorylation at other C-terminal sites, leading to an overall dominant-negative effect of STREX phosphorylation on BK channel activity (i.e., a single STREX-containing α subunit within a tetrameric channel is sufficient to flip PKA-mediated phosphorylation from stimulatory to inhibitory) (Tian et al., 2004). Furthermore, this inhibitory effect of PKA on BK channel activity appears to depend upon the presence of palmitoyl fatty acid groups within the STREX insert (Shipston, 2014), as palmitoylation-incompetent BK channels do not undergo PKA-mediated phosphorylation of the STREX insert and a decrease in activity (Tian et al., 2008). Collectively, these findings suggest that presence of STREX insert will lead to association of a C-terminal domain with the plasma membrane, which appears necessary for PKA-mediated phosphorylation within the STREX insert and inhibition of channel activity. Interestingly, presence of the STREX insert also appears to prevent the inhibitory effect of protein kinase C (PKC) on BK channel opening, possibly by inducing a conformation that precludes PKC-induced phosphorylation of Ser695 within the linker joining RCK1 and RCK2 domains (Zhou et al., 2012).

In addition to Ser/Thr phosphorylation, BK channels also undergo direct Tyr phosphorylation in the presence Src family kinases (i.e., c-Src and Hck) and the Ca2+-sensitive tyrosine kinase Pyk-2 (Ling et al., 2000, 2004; Alioua et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2012). Functionally, direct tyrosine phosphorylation of the BKα subunit has been reported to either increase (Ling et al., 2000, 2004; Yang et al., 2012) or decrease (Alioua et al., 2002) channel activity, although the reason(s) for this discrepancy remains unclear. Work from our group has shown that Phe substitution of Tyr766 in the C-terminus largely inhibits c-Src-induced BKα subunit phosphorylation, but does not appear to disrupt Pyk-2 mediated modification (Ling et al., 2000, 2004). Future studies examining the direct phosphorylation of native BK channels by tyrosine kinases in situ are needed to clarify the physiologic importance of this regulatory event.

Endogenous regulatory molecules

Endogenous molecules (e.g., heme, carbon monoxide (CO), reactive oxygen species) have been reported to interact with the BK channel complex (for review, see Hou et al., 2009). Similarly, acidification of the cytosol (i.e., pH 6.5) is able to increase BK channel activation by left-shifting the voltage dependence by ~45 mV, but such effects can be readily masked by physiological levels of free Mg2+ (i.e., 1 mM) and Ca2+ (i.e., 1 μM) (Avdonin et al., 2003). The importance of [H+] with regards to BK channel activity may become more apparent during pathological conditions where fluctuations in [H+] and [Ca2+] may occur (e.g., cerebral ischemia) (Lipton, 1999).

The linker between the RCK1 and RCK2 regions of the BKα subunit (Figure 1) reportedly contains a binding site for intracellular heme molecules (Hou et al., 2009). Application of heme to the cytosolic face of BK channels was found to inhibit channel opening with an IC50 ~70 nM (Tang et al., 2003), likely via an allosteric process. Moreover, the direction of gating modulation by heme appears to be closely-linked to membrane potential, as BK channel Po is enhanced at negative membrane potentials and inhibited at positive potentials. Heme regulators, transporters and degradation products (e.g., CO) are currently under investigation for their therapeutic potential in influencing BK channel activity and thus, global membrane potential (Hou et al., 2009).

Soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) contains an iron (heme) center that serves to bind NO, however, this site is also targeted by CO, which can activate sGC, leading to increased cytosolic [cGMP], PKG activation and enhanced BK channel activity (see Figure 2B). It has been further suggested that CO, along with NO, can also directly augment BK channel activity when applied at sufficiently-high concentrations (Hou et al., 2009; Leffler et al., 2011). Further examination of the physiologic contribution of such effects to BK channel regulation are warranted.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are reported to influence BK channel behavior include hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), superoxide (O−2) and peroxynitrite (ONOO−). Increased levels of ROS may occur under localized conditions, such as atherosclerosis (Li and Förstermann, 2009) and are particularly troublesome, as H2O2 and O−2 will react with free NO to generate ONOO−, thereby reducing NO bioavailability and cGMP/PKG signaling in vascular smooth muscle. For detailed discussions on impact of ROS on BK channel activity, the reader is referred to excellent review articles (Tang et al., 2004; Hou et al., 2009).

Regulation of BK channel expression by ubiquitination

Protein ubiquitination has emerged as a ubiquitous quality control mechanism for the regulation of protein trafficking and turnover and has been implicated in the dynamic control of diverse cellular processes (e.g., gene transcription, synaptic development and plasticity, oncogenesis, etc.) (Hershko and Ciechanover, 1998). Protein ubiquitination functions as a tagging system to mark proteins for degradation by the 26S proteasome complex and the human genome is reported to contain >600 genes encoding E3 ubiquitin ligases (Li et al., 2008), the enzyme responsible for conjugating ubiquitin monomers to target substrates. Given this level of abundance, the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) appears to enzymatically parallel protein phosphorylation, for which ~520 putative kinase genes have been described (Manning et al., 2002), as a widespread mechanism for protein modification and the regulation of cellular function. Recent evidence indicates that BK channels also undergo ubiquitination, which appears to have important functional implications. In the CNS, interaction of BK channels with cereblon (Jo et al., 2005), a substrate receptor for the CRL4A E3 ligase, leads to ubiquitination of the BKα subunit and retention of modified channels in the endoplasmic reticulum (Liu et al., 2014). Preventing ubiquitination of BK channels by pharmacologic or genetic interference of the CRL4A enzyme complex leads to increased trafficking of BK channels to the neuronal cell membrane and a higher incidence of seizure induction and epilepsy in mice. Such data point to ubiquitination as an important quality control mechanism to limit BK channel expression in neurons, which will ultimately impact membrane excitability. Given that cereblon transcripts are also widely expressed in tissues outside the CNS, this regulatory paradigm may have broader functional importance. As noted above, disruption of the neuronal chaperone CSPα in mice also elevates BK channel expression, suggesting that increased channel density be a common contributing factor to excitation-related neuropathologies.

In VSM, BKβ 1 subunits are reported to undergo ubiquitination in cultured myocytes exposed to high glucose and in arteries obtained from mice made diabetic by injection of streptozotocin, a pancreatic β-cell poison. Diabetes-like conditions elevate the expression of a muscle-specific RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligase via enhanced NF-κ B transcriptional activity, leading to increased BKβ 1 subunit ubiquitination and proteolysis (Yi et al., 2014). As previously described, loss of the BKβ 1 subunit would be expected to decrease Ca2+- and voltage-dependent activation of VSM BK channels (Brenner et al., 2000b), leading to exaggerated membrane depolarization and smooth muscle contraction. As BKβ 1 subunits may be capable of dynamically assembling with BKα subunits at the membrane (Leo et al., 2014), ubiquitination of BKβ 1 alone may not necessarily result in a decreased cellular level of BKα subunits.

Concluding remarks

BK channel activity is regulated both directly and indirectly through a diverse range of modulatory pathways involving covalent modifications, metabolic factors, trafficking events and transcriptional processes (see Figure 3). Given the formidable effect that BK channels can exert on membrane excitability, as a result of their large single channel conduction and dual activation by membrane depolarization/cytosolic free Ca2+, such “fine-tuning” affords cells the ability to precisely control the impact of these channels on their function and responsiveness to both acute and chronic stimuli. As reinforced by the accompanying articles in this thematic issue, BK channels represent powerful effectors in tissue health and dysfunction and that understanding their modes of regulation may lead to novel therapeutic strategies in disease treatment.

Figure 3.

A summary of cellular events/factors leading to BK channel activation (open pore) and deactivation/inactivation (closed pore). Abbreviations: Em, membrane potential; STREX, stress-axis regulated exon; PKC, protein kinase C; Ser, serine.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research funding to APB from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council.

Author note

Lingle and coworkers have demonstrated that the γ1 subunit (i.e., LRRC26) mediated leftward shift in BK channel gating occurs in an all-or-none fashion, in contrast to the incremental shifts in gating produced by stoichiometric association of BKβ1 subunits (Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 4873, 2014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322123111). Subsequently, Evanson et al. (2014) have reported that LRRC26 is endogenously expressed in rat cerebral vascular myocytes and may function as an auxiliary γ1 subunit by altering the voltage and calcium sensitivity of BK channel gating (Circ. Res. 115, 423–431. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303407).

References

- Ahrendt E., Kyle B. D., Braun A. P., Braun J. E. (2014). Cysteine string protein limits express of the large conductance, calcium-activated K+ (BK) channel. PLoS ONE 9:e86586 10.1371/journal.pone.0086586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alioua A., Lu R., Kumar Y., Eghbali M., Kundu P., Toro L., et al. (2008). Slo1 caveolin-binding motif, a mechanism of caveolin-1-Slo1 interaction regulating Slo1 surface expression. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 4808–4817 10.1074/jbc.M709802200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alioua A., Mahajan A., Nishimaru K., Zarei M. M., Stefani E., Toro L. (2002). Coupling of c-Src to large conductance voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channels as a new mechanism of agonist-induced vasoconstriction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 14560–14565 10.1073/pnas.222348099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg G. C., Bonev A. D., Rossow C. F., Nelson M. T., Santana L. F. (2003). Modulation of the molecular composition of large conductance, Ca2+ activated K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle hypertension. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 717–724 10.1172/JCI200318684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amberg G. C., Santana L. F. (2003). Downregulation of the BK channel β1 subunit in genetic hypertension. Circ. Res. 93, 965–971 10.1161/01.RES.0000100068.43006.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avdonin V., Tang X. D., Hoshi T. (2003). Stimulatory action of internal protons on Slo1 BK channels. Biophys. J. 84, 2969–2980 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70023-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin M., Wang H. Z., Zhang X., Chua R., Downing K., Melman A., et al. (2012). Large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel activity, as determined by whole-cell patch clamp recording, is decreased in urinary bladder smooth muscle cells from male rats with partial urethral obstruction. BJU Int. 110, E402–E408 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11137.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielefeldt K., Jackson M. B. (1993). A calcium-activated potassium channel causes frequency-dependent action potential failures in a mammalian nerve terminal. J. Neurophysiol. 70, 284–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner R., Chen Q. H., Vilaythong A., Toney G. M., Noebels J. L., Aldrich R. W. (2005). BK channel β4 subunit reduces dentate gyrus excitability and protects against temporal lobe seizures. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1752–1759 10.1038/nn1573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner R., Jegla T. J., Wickenden A., Liu Y., Aldrich R. W. (2000a). Cloning and functional characterization of novel large conductance calcium-activated potassium channel β subunits, hKCNMB3 and hKCNMB4. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 6453–6461 10.1074/jbc.275.9.6453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner R., Perez G., Bonev A. D., Eckman D. M., Kosek J. C., Wiler S. W., et al. (2000b). Vasoregulation by the β1 subunit of the calcium-activated potassium channel. Nature 407, 870–876 10.1038/35038011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdyga T., Wray S. (2005). Action potential refractory period in ureter smooth muscle is set by Ca sparks and BK channels. Nature 436, 559–562 10.1038/nature03834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S., Gomes C. M., Hypolite J. A., Marx J., Alanzi J., Zderic S. A., et al. (2010). Detrusor overactivity is assoicated with downregulation of large-conductance calcium- and voltage-activated potassium channel protein. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 298, F1416–F1423 10.1152/ajprenal.00595.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ G. J., Hodges S. (2006). Molecular mechanisms of detrusor and corporal myocyte contraction: identifying tragets for pharmacotherapy of bladder and erectile dysfunction. Br. J. Pharmacol. 147, S41–S55 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras G. F., Neely A., Alvarez O., Gonzalez C., Latorre R. (2012). Modulation of BK channel voltage gating by different auxiliary β subunits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 18991–18996 10.1073/pnas.1216953109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui J., Yang H., Lee U. S. (2009). Molecular mechanisms of BK channel activation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 852–875 10.1007/s00018-008-8609-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. J., Wu X., Nurkiewicz T. R., Kawasaki J., Gui P., Hill M. A., et al. (2001). Regulation of ion channels by protein tyrosine phosphorylation. Am. J. Physiol. 281, H1835–H1862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelier J., Braun J. E. (2014). CSPα - Chaperoning presynaptic proteins. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8:116 10.3389/fncel.2014.00116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W., Bautista J. F., Yang H., Diez-Sampdero A., You S. A., Wang L., et al. (2005). Calcium-sensitive potassium channelopathy in human epilepsy and paroxysmal movement disorder. Nat. Genet. 7, 733–738 10.1038/ng1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England S. K., Wooldridge T. A., Stekiel W. J., Rusch N. J. (1993). Enhanced single-channel K+ current in arterial membranes from genetically hypertensive rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 264, H1337–H1345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber E. S., Sah P. (2003). Calcium-activated potassium channels: multiple contributions to neuronal function. Neuroscientist 9, 181–194 10.1177/1073858403009003011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakler B., Adelman J. P. (2008). Control of KCa channels by calcium nano/microdomains. Neuron 59, 873–881 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil R., Lohmann S. M., De Jonge H. R., Walter U., Hofmann F. (2003). Cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases and the cardiovascular system: insights from genetically modified mice. Circ. Res. 93, 907–916 10.1161/01.RES.0000100390.68771.CC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Chacon R., Wolfel M., Nishimune H., Tabares L., Schmitz F., Castellano-Munoz M., et al. (2004). The synaptic vesicle protein CSPα prevents presynaptic degeneration. Neuron 42, 237–251 10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00190-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fernández J. M., Tomás M., Vázquez E., Orlo P., Latorre R., Senti M., et al. (2004). Gain-of-function mutation in the KCNMB1 potassium channel subunit is associated with low prevalence of diastolic hypertension. J. Clin. Invest. 113, 1032–1039 10.1172/JCI200420347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I., Busse R. (2003). Molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 284, R1–R12 10.1152/ajpregu.00323.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis S. H., Busch J. L., Corbin J. D. (2010). cGMP-dependent protein kinases and cGMP phosphodiesterases in nitric oxide and cGMP action. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 525–563 10.1124/pr.110.002907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu N., Vervaeke K., Storm J. F. (2007). BK potassium channels facilitate high-frequency firing and cause early spike frequency adaptation in rat CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells. J. Physiol. 580, 859–882 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.126367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghdoost-Yazdi H., Janahmadi M., Behzadi G. (2008). Iberiotoxiin-sensitive large conductance Ca2+-dependent K+ (BK) channels regulate the spike configuration in the burst firing of cerebellar Purkinje neurons. Brain Res. 1212, 1–8 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heppner T. J., Bonev A. D., Nelson M. T. (1997). Ca2+-activated K+ channels regulate action potential repolarization in urinary bladder smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 273, C110–C117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko A., Ciechanover A. (1998). The ubiquitin system. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 425–479 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi T., Pantazis A., Olcese R. (2013). Transduction of voltage and Ca2+ signals by Slo1 BK channels. Physiology 28, 172–189 10.1152/physiol.00055.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S., Heinemann S. H., Hoshi T. (2009). Modulation of BKCa channel gating by endogenous signaling molecules. Physiology 4, 26–35 10.1152/physiol.00032.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hristov K. L., Chen M., Kellett W. F., Rovner E. S., Petkov G. V. (2011). Large-conductance voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channels regulate human detrusor smooth muscle function. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 301, C903–C912 10.1152/ajpcell.00495.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H., Shao L.-R., Chavoshy S., Gu N., Trieb M., Behrens R., et al. (2001). Presynaptic Ca2+-activated K+ channels in glutamatergic hippocampal terminals and their role in spike repolarization and regulation of transmitter release. J. Neurosci. 21, 9585–9597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlach W. L., Finch S. C., Dunlop J., Meredith A. L., Aldrich R. W., Dalziel J. E. (2008). The molecular mechanims of “ryegrass staggers,” a neurological disorder of K+ channels. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 327, 657–664 10.1124/jpet.108.143933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa N. P., Hudspeth A. J. (1994). Clustering of Ca2+ channels and Ca2+-activated K+ channels at fluorescently labeled presynaptic active zones of hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 7578–7582 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo S., Lee K.-H., Song S., Jung Y.-K., Park C.-S. (2005). Identification and functional characterization of cereblon as a binding protein for large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel in rat brain. J. Neurochem. 94, 1212–1224 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03344.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B. E., Glauser D. A., Dan-Glauser E. S., Halling B., Aldrich R. W., Goodman M. B. (2011). Alternatively spliced domains interact to regulate BK potassium channel gating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 20784–20789 10.1073/pnas.1116795108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph B. K., Thakali K. M., Moore C. L., Rhee S. W. (2013). Ion channel remodeling in vascular smooth muscle during hypertension: implications for novel therapeutic approaches. Pharmacol. Res. 70, 126–138 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczorowski G. J., Garcia M. L. (1999). Pharmacology of voltage-gated and calcium-activated potassium channels. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3, 448–458 10.1016/S1367-5931(99)80066-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus H.-G., Folander K., Garcia-Calvo M., Garcia M. L., Kaczorowski G. J., Smith M., et al. (1994a). Primary sequence and immunological characterization of β-subunit of high conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel from smooth muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 17274–17278 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaus H.-G., McManus O. B., Lee S. H., Schmalhofer W. A., Garcia-Calvo M., Helms L. M., et al. (1994b). Tremorogenic indole alkaloids potentialy inhibit smooth muscle high-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Biochem 33, 5819–5828 10.1021/bi00185a021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle B. D., Ahrendt E., Braun A. P., Braun J. E. (2013a). The large conductance, calcium-activated K+ (BK) channel is regulated by cysteine string protein. Sci. Rep. 3:2447 10.1038/srep02447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle B. D., Bradley E., Large R., Sergeant G. P., McHale N. G., Thornbury K. D., et al. (2013b). Mechanisms underlying activation of transient BK current in rabbit urethral smooth muscle cells and its modulation by IP3-generating agonists. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 305, C609–C622 10.1152/ajpcell.00025.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyle B. D., Hurst S., Swayze R. D., Sheng J.-Z., Braun A. P. (2013c). Specific phosphorylation sites underlie the stimulation of a large conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channel by cGMP-dependent protein kinase. FASEB J. 27, 2027–2038 10.1096/fj.12-223669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latorre R., Oberhauser A., Labarca P., Alvarez O. (1989). Varieties of calcium-activated potassium channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 51, 385–399 10.1146/annurev.ph.51.030189.002125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leffler C. W., Parfenova H., Jaggar J. H. (2011). Carbon monoxide as an endogenous vascular modulator. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 301, H1–H11 10.1152/ajpheart.00230.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo M. D., Bannister J. P., Narayanan D., Nair A., Grubbs J. E., Gabrick K. S., et al. (2014). Dynamic regulation of β1 subunit trafficking controls vascular contractility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 2361–2366 10.1073/pnas.1317527111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Förstermann U. (2009). Prevention of atherosclerosis by interference with the vascular nitric oxide system. Curr. Pharm. Des. 15, 3133–3145 10.2174/138161209789058002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Bengston M. H., Ulbrich A., Matsuda A., Reddy V. A., Orth A., et al. (2008). Genome-wide and functional annotation of human E3 ubiquitin ligases identifies MULAN, a mitochondrial E3 that regulates the organelle's dynamics and signaling. PLoS ONE 3:e1487 10.1371/journal.pone.0001487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M. T., Hessinger D. A., Pearce W. J., Longo L. D. (2006). Modulation of BK channel calcium affinity by differential phosphorylation in developing ovine basilar artery myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 291, H732–H740 10.1152/ajpheart.01357.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M. T., Longo L. D., Pearce W. J., Hessinger D. A. (2005). Ca2+-activated K+ channel-associated phosphatase and kinase activities during development. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 289, H414–H425 10.1152/ajpheart.01079.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling S., Sheng J.-Z., Braun A. P. (2004). The calcium-dependent activity of large-conductance, calcium-activated K+ channels is enhanced by Pyk2- and Hck-induced tyrosine phosphorylation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 287, C698–C706 10.1152/ajpcell.00030.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling S., Woronuk G., Sy L., Lev S., Braun A. P. (2000). Enhanced activity of a large conductance, calcium-sensitive K+ channel in the presence of Src tyrosine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 30683–30689 10.1074/jbc.M004292200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton P. (1999). Ischemic cell death in brain neurons. Physiol. Rev. 79, 1431–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G., Zakharov S. I., Yang L., Wu R. S., Deng S. X., Landry D. W., et al. (2008). Locations of the β1 transmembrane helices in the BK potassium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 10727–10732 10.1073/pnas.0805212105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Ye J., Zou X., Xu Z., Feng Y., Zou X., et al. (2014). CRL4ACRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase restricts BK channel activity and prevents epileptogenesis. Nat. Commun. 5:3924 10.1038/ncomms4924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Hudetz A. G., Knaus H.-G., Rusch N. J. (1998). Increased expression of Ca2+-sensitive K+ channels in the cerebral microcirculation of genetically hypertensive rats. evidence for their protection against cerebral vasospasm. Circ. Res. 82, 729–737 10.1161/01.RES.82.6.729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Z., Lou X. J., Horrigan F. T. (2006). Role of charged residues in the S1-S4 voltage sensor of BK channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 127, 309–328 10.1085/jgp.200509421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning G., Whyte D. B., Martinez R., Hunter T., Sudarsanam S. (2002). The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science 298, 1912–1934 10.1126/science.1075762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrion N. V., Tavalin S. J. (1998). Selective activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels by co-localized Ca2+ channels in hippocampal neurons. Nature 395, 900–905 10.1038/27674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith A. L., Thorneloe K. S., Werner M. E., Nelson M. T., Aldrich R. W. (2004). Overactive bladder and incontinence in the absence of the BK large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36746–36752 10.1074/jbc.M405621200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morera F., Alioua A., Kundu P., Salazar M., Gonzalez C., Martinez A. D., et al. (2012). The first transmembrane domain (TM1) of β2-subunit binds to the transmembrane domain S1 of α-subunit in BK potassium channels. FEBS Lett. 586, 2287–2293 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.05.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow J. P., Zakharov S. I., Liu G., Yang L., Sok A. J., Marx S. O. (2006). Defining the BK channel domains required for β1-subunit modulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 5096–5101 10.1073/pnas.0600907103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzel T., Feil R., Mülsch A., Lohmann S. M., Hofmann F., Walter U. (2003). Physiology and pathophysiology of vascular signaling controlled by cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Circulation 108, 2172–2183 10.1161/01.CIR.0000094403.78467.C3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nara M., Dhulipala P. D., Wang Y. X., Kotlikoff M. I. (1998). Reconstitution of β-adrenergic modulation of large conductance, calcium-activated potassium (Maxi-K) channels in Xenopus oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 14920–14924 10.1074/jbc.273.24.14920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardi A., Olesen S. P. (2008). BK channel modulators: a comprehensive overview. Curr Med. Chem. 15, 1126–1146 10.2174/092986708784221412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen T., Sølvsten Burgdorf K., Grarup N., Borch-Johnsen K., Hansen T., Jørgensen T., et al. (2008). The KCNMB1 Glu65Lys polymorphism associates with reduced systolic and diastolic blodd pressure in the Inter99 study of 5729 Danes. J. Hypertension 26, 2142–2146 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32830b894a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieves-Cintrón M., Amberg G. C., Nichols C. B., Molkentin J. D., Santana L. F. (2007). Activation of NFATc3 down-regulates the β1 subunit of large conductance, calcium-actiated K+ channels in arterial smooth muscle and contributes to hypertension. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3231–3240 10.1074/jbc.M608822200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nourian Z., Li M., Leo M. D., Jaggar J. H., Braun A. P., Hill M. A. (2014). Large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel (BKCa) α-subunit splice variants in resistance arteries from rat cerebral and skeletal muscle vasculature. PLoS ONE 9:e98863 10.1371/journal.pone.0098863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oger S., Behr-Roussel D., Gorny D., Bernabé J., Comperat E., Chartier-Kastler E., et al. (2010). Efects of potassium chanel modulators on myogenic spontaneous phasic contractile activity in human detrusor from neurogenic patients. BJU Int. 108, 604–611 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohi Y., Yamamura H., Nagano N., Ohya S., Muraki K., Watanabe M., et al. (2001). Local Ca2+ transients and distribution of BK channels and ryanodine receptors in smooth muscle cells of guinea-pig vas deferens and urinary bladder. J. Physiol. 534, 313–326 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-3-00313.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohya S., Fujimori T., Kimura T., Yamamura H., Imaizumi Y. (2010). Novel spliced variants of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+-channel β2-subunit in human and rodent pancreas. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 114, 198–205 10.1254/jphs.10159FP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez G. J., Bonev A. D., Patlak J. B., Nelson M. T. (1999). Functional coupling of ryanodine receptors to KCa channels in smooth muscle cells from rat cerebral arteries. J. Gen. Physiol. 113, 229–237 10.1085/jgp.113.2.229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkov G. V., Bonev A. D., Heppner T. J., Brenner R., Aldrich R. W., Nelson M. T. (2001). β1-Subunit of the Ca2+-activated K+ channel regulates contractile activity of mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 537, 443–452 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00443.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plüger S., Faulhaber J., Fürstenau M., Löhn M., Waldschutz R., Gollasch M., et al. (2001). Mice with disrupted BK channel β1 subunit gene feature abnormal Ca2+ spark/STOC coupling and elevated blood pressure. Circ. Res. 87, e53–e60 10.1161/01.RES.87.11.e53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen A. N., Wulf H., Hay-Schmidt A., Jansen-Olesen I., Olesen J., Klaerke D. A. (2009). Differential expression of BK channel isoforms and β-subunits in rat neuro-vascular tissues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788, 380–389 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli G., Saviane C., Mohajerani M. H., Pedarzani P., Cherubini E. (2004). BK potassium channels control transmitter release at CA3-CA3 synapses in rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. 557, 147–157 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.062661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart P. H., Chung S., Martin B. L., Brautigan D. L., Levitan I. B. (1991). Modulation of calcium-activated potassium channels from rat brain by protein kinase A and phosphatase 2A. J. Neurosci. 11, 1627–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart P. H., Levitan I. B. (1995). Kinase and phosphatase activities intimately associated with a reconstituted calcium-dependent potassium channel. J. Neurosci. 15, 4572–4579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts W. M., Jacobs R. A., Hudspeth A. J. (1990). Colocalization of ion channels involved in frequency selectivity and synaptic transmission at presynaptic active zones of hair cells. J. Neurosci. 10, 3664–3684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robitaille R., Charlton M. P. (1992). Presynaptic calcium signals and transmitter release are modulated by calcium-activated potassium channels. J. Neurosci. 12, 297–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch N. J., De Lucena R. G., Wooldridge T. A., England S. K., Cowley A. W., Jr. (1992). A Ca2+-dependent K+ current is enhanced in arterial membranes of hypertensive rats. Hypertension 19, 301–307 10.1161/01.HYP.19.4.301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusch N. J., Runnells A. M. (1994). Remission of high blood pressure reverses arterial potassium channel alterations. Hypertension 23, 941–945 10.1161/01.HYP.23.6.941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders K. M. (2008). Regulation of smooth muscle excitation and contraction. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 20, 39–53 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01108.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansom S. C., Stockand J. D., Hall D., Williams B. (1997). Regulation of large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels by protein phosphatase 2A. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9902–9906 10.1074/jbc.272.15.9902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sausbier M., Hu H., Arntz C., Feil S., Kamm S., Adelsberger H., et al. (2004). Cerebellar ataxia and Purkinje cell dysfunction caused by Ca2+-activated K+ channel deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9474–9478 10.1073/pnas.0401702101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert R., Nelson M. T. (2001). Protein kinases: tuners of the BKCa channel in smooth muscle. TIPS 22, 505–512 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01775-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seibold M. A., Wang B., Eng C. E., Kumar G., Beckman K. B., Sen S., et al. (2008). An african-specific functional polymorphism in KCNMB1 shows sex-specific association with asthma severity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 2681–2690 10.1093/hmg/ddn168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K.-Z., Lagrutta A., Davies N. W., Standen N. B., Adelman J. P., North R. A. (1994). Tetraethylammonium block of Slowpoke calcium-activated potassium channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes: evidence for tetrameric channel formation. Pflügers Arch. 426, 440–445 10.1007/BF00388308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipston M. J. (2001). Alternative splicing of potassium channels: a dynamic switch of cellular excitability. Trends Cell Biol. 11, 353–358 10.1016/S0962-8924(01)02068-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipston M. J. (2014). Ion channel regulation by protein S-acylation. J. Gen. Physiol. 143, 659–678 10.1085/jgp.201411176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H., Stefani E., Toro L. (2012). Intracellular BKCa (iBKCa) channels. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 590, 5937–5947 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.215533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprossmann F., Pankert P., Sausbier U., Wirth A., Zhou X.-B., Madlung J., et al. (2009). Inducible knockout mutagenesis reveals compensatory mechanisms elicited by constitutive BK channel deficiency in overactive murine bladder. FEBS Lett. 276, 1680–1697 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06900.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka Y., Meera P., Song M., Knaus H.-G., Toro L. (1997). Molecular constituents of maxi-KCa channels in human coronary smooth muscle: predominant α + β subunit complexes. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 502, 545–557 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.545bj.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X. D., Santarelli L. C., Heinemann S. H., Hoshi T. (2004). Metabolic regulation of potassium channels. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 66, 131–159 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.041002.142720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X. D., Xu R., Reynolds M. F., Garcia M. L., Heinemann S. H., Hoshi T. (2003). Haem can bind to and inhibit mammalian calcium-dependent Slo1 BK channels. Nature 425, 531–535 10.1038/nature02003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. S., Buechler J. A., Yonemoto W. (1990). cAMP-dependent protein kinase: framework for a diverse family of regulatory enzymes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 59, 971–1005 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.004543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorneloe K. S., Nelson M. T. (2005). Ion channels in smooth muscle: regulators of intracellular calcium and contractility. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 83, 215–242 10.1139/y05-016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Coghill L. S., McClafferty H., MacDonald S. H., Antoni F. A., Ruth P., et al. (2004). Distinct stoichiometry of BKCa channel tetramer phosphorylation specifies channel activation and inhibition by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 11897–11902 10.1073/pnas.0402590101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Duncan R. R., Hammond M. S., Coghill L. S., Wen H., Rusinova R., et al. (2001). Alternative splicing switches potassium channel sensitivity to protein phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 7717–7720 10.1074/jbc.C000741200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Jeffries O., McClafferty H., Molyvdas A., Rowe I. C., Saleem F., et al. (2008). Palmitoylation gates phosphorylation-dependent regulation of BK potassium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 21006–21011 10.1073/pnas.0806700106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L., Knaus H.-G., Shipston M. J. (1998). Glucocorticoid regulation of calcium-activated potassium channels mediated by serine/threonine protein phosphatase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 13531–13536 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toro B., Cox N., Wilson R. J., Garrido-Sanabria E., Stefani E., Toro L., et al. (2006). KCNMB1 regulates surface expression of a voltage and Ca2+-activated K+ channel via endocytic trafficking signals. Neuroscience 142, 661–669 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uebele V. N., Lagrutta A., Wade T., Figueroa D. J., Liu Y., McKenna E., et al. (2000). Cloning and functional expression of two families of β-subunits of the large conductance calcium-activated K+ channel. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23211–23218 10.1074/jbc.M910187199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallner M., Meera P., Toro L. (1999). Molecular basis f fast inactivation in voltage and Ca2+-activated K+ channels: a tranmembrane β-subunit homolog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 4137–4142 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Rothberg B. S., Brenner R. (2006). Mechanism of β4 subunit modulation of BK channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 127, 449–465 10.1085/jgp.200509436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Rothberg B. S., Brenner R. (2009). Mechanism of increased BK channel activation from a channel mutation that causes epilepsy. J. Gen. Physiol. 133, 283–294 10.1085/jgp.200810141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimalawansa S. (2008). Nitric oxide: new evidence for novel therapeutic indications. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 9, 1935–1954 10.1517/14656566.9.11.1935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., McCobb D. P. (1998). Control of alternative splicing of potassium channels by stress hormones. Science 280, 443–446 10.1126/science.280.5362.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Aldrich R. W. (2010). LRRC26 auxiliary protein allow BK channel activation at resting voltage without calcium. Nature 466, 513–517 10.1038/nature09162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Aldrich R. W. (2012). BK potassium channel modulation by leucine-rich repeat-containing proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7917–7922 10.1073/pnas.1205435109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Olsen J. V., Park K. S., Li W., Bildl W., Schulte U., et al. (2008). Profiling the phospho-status of the BKCa channel α subunit in rat brain reveals unexpected patterns and complexity. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 7, 2188–2198 10.1074/mcp.M800063-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Krishnamoorthy G., Saxena A., Zhang G., Shi J., Yang H., et al. (2010). An epilepsy/dyskinesia-associated mutation enhances BK channel activation by potentiating Ca2+ sensing. Neuron 66, 871–883 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Li P.-Y., Cheng J., Mao L., Wen J., Tan X.-Q., et al. (2013). Function of BKCa channels is reduced in human vascular smooth muscle cells from Han Chinese patients with hypertension. Hypertension 61, 519–525 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Murphy T. V., Ella S. R., Grayson T. H., Haddock R., Hwang Y. T., et al. (2009). Heterogeneity in function of small artery smooth muscle BKCa: involvement of the β1-subunit. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 587, 3025–3044 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.169920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Wu X., Gui P., Wu J., Sheng J.-Z., Ling S., et al. (2012). α5β1 integrin engagement increases large conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channel current and Ca2+ sensitivity through cSrc-mediated channel phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 131–141 10.1074/jbc.M109.033506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi F., Wang H., Chai Q., Wang X., Shen W.-K., Willis M., et al. (2014). Regulation of large conducatnce Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channel β1 subunit expression by muscle RING finger protein 1 in diabetic vessels. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 10853–10864 10.1074/jbc.M113.520940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan P., Leonetti M. D., Hsiung Y., MacKinnon R. (2012). Open structure of the Ca2+ gating ring in the high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Nature 481, 94–98 10.1038/nature10670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan P., Leonetti M. D., Pico A., Hsiung Y., MacKinnon R. (2010). Structure of the human BK channel Ca2+-activation apparatus at 3.0 Å resolution. Science 329, 182–186 10.1126/science.1190414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarei M. M., Song M., Wilson R. J., Cox N., Colom L. V., Knaus H.-G., et al. (2007). Endocytic trafficking signals in KCNMB2 regulate surface expression of a large conductance voltage and Ca2+-activated K+ channel. Neuroscience 147, 80–89 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Wulfsen I., Korth M., McClafferty H., Lukowski R., Shipston M. J., et al. (2012). Palmitoylation and membrane association of the stress axis regulated insert (STREX) controls BK channel regulation by protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 32161–32171 10.1074/jbc.M112.386359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.-B., Ruth P., Schlossmann J., Hofmann F., Korth M. (1996). Protein phosphatase 2A is essential for the activation of Ca2+-activated K+ currents by cGMP-dependent protein kinase in tracheal smooth muscle and chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19760–19767 10.1074/jbc.271.33.19760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.-B., Wulfsen I., Utku E., Sausbier U., Sausbier M., Wieland T., et al. (2010). Dual role of protein kinase C on BK channel regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 8005–8010 10.1073/pnas.0912029107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZhuGe R., Fogarty K. E., Tuft R. A., Walsh J. V., Jr. (2002). Spontaneous transient outward currents arise from microdomains where BK channels are exposed to a mean Ca2+ concentration on the order of 10 μM during a Ca2+ spark. J. Gen. Physiol. 120, 15–27 10.1085/jgp.20028571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]