INTRODUCTION

Shoulder pain is the third most common musculoskeletal presentation in primary care after back and knee pain. Annually 1% of adults are likely to consult with new shoulder pain. The four most common underlying causes are rotator cuff disorders (85% of cases), glenohumeral disorders, acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) pathology, and referred neck pain. Although the vast majority of cases are treated satisfactorily, chronicity and recurrence are common, with estimates of 14% of patients still consulting 3 years on.

HISTORY

Look for the following red flags that indicate the need for urgent investigations and/or referral to secondary care: acute presentation with a history of trauma (especially if pain restricts all passive and active movements); systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, weight loss, or new respiratory symptoms; abnormal joint shape; local mass or swelling; local erythema over a ‘hot’, tender joint; and severe restriction of movement.

Enquire about the following:

patient’s occupation; which may be relevant, especially if it involves repetitive arm movements and prolonged elevation;

the onset of pain, its nature, duration, aggravating and relieving factors;

whether the pain is constant, suggesting active joint inflammation;

pain in other joints, suggesting the possibility of osteoarthritis or a systemic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis; and

history of malignancy such as lung or breast cancer.

EXAMINATION

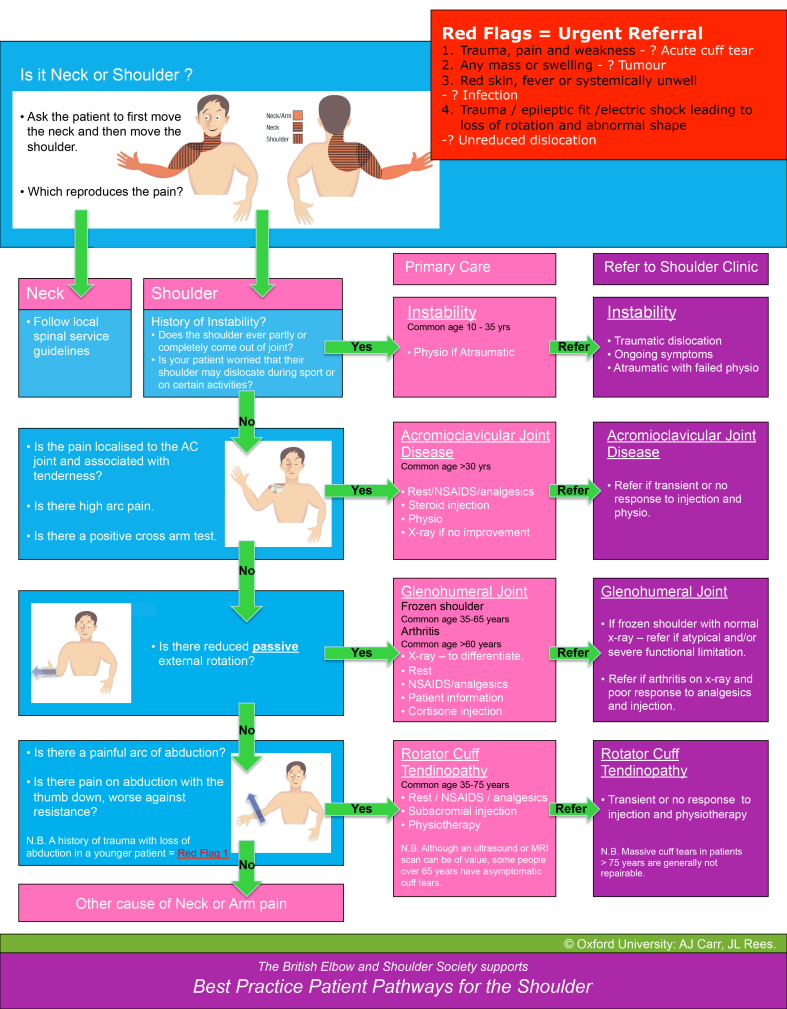

The focus should be on the four most common problems. Appendix 1 will help guide diagnosis, treatment, and referral decisions. None of the many specific clinical examination tests suggested for diagnosing shoulder and neck pain has high sensitivity and specificity.1,2

Pain referred from the neck is often associated with neck movement and sometimes with nerve root compression producing paraesthesia, weakness, and altered tendon reflexes. Spurling’s test (pain when extending and rotating the head to the affected side while pressing down on the head) might further help indicate cervical radiculopathy, with low to moderate sensitivity (30–90%) and high specificity (74–100%).3

Clinical tests to diagnose ACJ disorder are of limited diagnostic value.2 Exclusive tenderness over the joint has a high sensitivity of 90–95%, however it has a poor specificity of 10%. The cross adduction test (pain when bringing arms across chest to touch the opposite shoulder) has sensitivity of 77–100% and specificity of 79%.

Reduced range of passive external rotation is the principle diagnostic test for contracted frozen shoulder (adhesive capsulitis).2 It is also reduced in advanced glenohumeral arthropathy, but no evidence is available for its diagnostic accuracy in primary care.

Impingement tests include Hawkin’s test (pain on rotating the arm internally while flexed at 90°) with a sensitivity and specificity of 80–92% and 25–60%, respectively.1 The painful arc test (pain at mid-range of active abduction) has sensitivity and specificity of 32–97% and 10–80% respectively. Jobe’s test (resisted elevation with the arm at 90° and the thumb pointing down) has sensitivity and specificity of 77–95% and 65–85% respectively.1 Tests to identify the specific tendon or muscle affected have a questionable utility in clinical practice due to poor diagnostic accuracy.1

INVESTIGATIONS

Blood tests (for example full blood count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate) may be indicated in the presence of red flags, for example, where an inflammatory process is suspected. Plain radiography is not initially indicated for non-traumatic shoulder pain of <4-weeks’ duration. However, it is useful with a history of trauma, symptoms lasting >4 weeks, significant movement restriction, unrelenting pain, and in the presence of red flags. It can also be useful when suspecting calcific tendinitis or arthritis in patients aged >35 years. Radiographs are usually normal in acute rotator cuff tears unless there is an associated greater tuberosity avulsion fracture.

Ultrasound scanning (USS) is useful in assessing soft tissues whereas magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is accurate in assessing both soft tissues and bones. Both MRI and USS are useful in secondary care and equally can be used for detecting full-thickness rotator cuff tears.4 The main advantage of USS is its relative lower cost, although it is operator dependent. There is evidence that, in expert hands, USS is good in detecting cuff tears with sensitivity and specificity of 90–100%.4 It is suggested it may also be useful in diagnosing bursitis, tenosynovitis, and impingement on dynamic scanning, but with little evidence for this claim.

The causal link between imaging findings and the clinical presentation in primary care is poor. In one study among healthy volunteers, the prevalence of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears identified when using an MRI scan was 34% and even higher at 54% among those aged >60 years old.5

TREATMENT

Pain control to achieve early return to normal function is the cornerstone of treatment. Paracetamol (1000 mg four times a day) should be the first-line medication. Depending on the severity of symptoms, another non-opioid analgesic could be added, such as ibuprofen tablets (200–400 mg three times a day). Look for contraindications such as a history of gastrointestinal tract (GIT) bleeding, ischaemic heart disease, or renal impairment. Alternatively, a mild opioid could be added such as codeine tablets (15–30 mg 4–6 hourly), although constipation, drowsiness, and confusion are common side effects.

There is some evidence for a short-term modest benefit for physiotherapy with home exercises for shoulder pain.6,7 There is no clear evidence on the best timing of referral for physiotherapy in primary care. Although corticosteroid shoulder injection is commonly used in practice, there is no clear evidence for its effectiveness compared with local anaesthetic alone.8 It is often repeated at 6 weeks, but there is no evidence for the most effective course or regimen, with some evidence now suggesting repeated injections may cause tendon damage.9 Corticosteroid injections are contraindicated in the presence of acute joint infection or systemic symptoms. Evidence is limited and of poor quality on whether using imaging (USS) improves the accuracy and outcomes of shoulder injection.

Explore the impact of symptoms on work and other relevant physical activities. Consider a short period of time off work (for example 1 week) if the job duties appear to be directly relevant to the shoulder symptoms. Early resumption of usual physical activities and return to work is beneficial to reduce the risk of long-term incapacity.

There is no clear evidence on the most appropriate time for follow-up. A pragmatic approach would be a review in 2 weeks, depending on the severity of symptoms, advising the patient to return sooner in case of deterioration.

REFERRAL

Urgent referral to secondary care is necessary in the presence of red flags. Otherwise engage with your patient in shared decision making. Early referral should be considered in the presence of associated joint instability or severe post-traumatic pain. A referral should also be considered if pain and disability are not improving after 3 months of treatment. Specialised musculoskeletal clinics, when available, can provide a good alternative service in accessing, or providing physiotherapy or injection treatments. However, onward referral of patients in need of specialist orthopaedic assessment should not be delayed.

Appendix 1.

Diagnosis of shoulder problems in primary care: guidelines on treatment and referral. Reproduced with permission.

Provenance

Freely submitted; not externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: www.bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Hegedus EJ, Goode AP, Cook CE, et al. Which physical examination tests provide clinicians with the most value when examining the shoulder? Update of a systematic review with meta-analysis of individual tests. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(14):964–978. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanchard NCA, Lenza M, Handoll HHG, Takwoingi Y. Physical tests for shoulder impingements and local lesions of bursa, tendon or labrum that may accompany impingement (review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD007427. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007427.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubinstein SM, Pool JJM, van Tulder MW, et al. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of provocative tests of the neck for diagnosing cervical radiculopathy. Eur Spine J. 2007;16(3):307–319. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0225-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenza M, Buchbinder R, Takwoingi Y, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance arthrography and ultrasonography for assessing rotator cuff tears in people with shoulder pain for whom surgery is being considered. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD009020. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009020.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sher JS, Uribe JW, Posada A, et al. Abnormal findings on magnetic resonance images of asymptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(1):10–15. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green S, Buchbinder R, Hetrick S. Physiotherapy interventions for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;2:CD004258. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM. Corticosteroid injections for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD004016. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coombes BK, Bisset L, Vicenzino B. Efficacy and safety of corticosteroid injections and other injections for management of tendinopathy: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9754):1751–1767. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61160-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dean B, Franklin S, Murphy R, et al. Glucocorticoids induce specific ion-channel mediated toxicity in tendon. Br J Sports Med. 2014 doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]