INTRODUCTION

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) estimates that each year in the UK around 2.5 million people will approach their GP with back pain. Fortunately most cases are due to non-specific causes and are often self-limiting.

Metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC) is one of the ominous causes of back pain where there is a compression of the thecal sac and its components by tumour mass. This is a true spinal emergency, and if the pressure on the spinal cord is not relieved quickly, it may result in irreversible loss of neurologic function. The most important prognostic factor for functional outcome is neurologic function before treatment.1 Hence, any delay could result in poorer functional outcome and decreased quality of life, with increased dependence on healthcare resources. There is a need for improving awareness among all clinicians so as to make prompt diagnosis and referral of MSCC a reality.2

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND AETIOLOGY

Bone is the third most common site of metastases after the liver and the lung. MSCC is seen in up to 5% of cancer patients; however, in up to 20% of MSCC cases, cord compression may be the first sign of malignancy.3 Although the exact incidence of MSCC is not known, intelligent estimates put the number at about approximately 4000 cases in England and Wales.4

The most common primary tumours that metastasize to the spine are breast, lung, prostate, and kidney tumours. Tumours may spread to the spine via the arterial route, vertebro-venous plexus, or by direct invasion. Once the tumour mass begins to grow it can cause spinal cord damage secondary to direct pressure, vascular compromise, and demyelination. Spinal cord compression could also occur due to the spinal instability caused by the collapse of vertebrae affected by the tumour.

PRESENTATION

The most common presenting feature for spinal metastases is increasing back pain. The pain may be localised or generalised and is due to compression, pathological fractures, or axial pain from mechanical instability. It often increases in recumbent position or with activities such as sneezing or coughing secondary to distension of the epidural venous plexus. Radicular pain may develop due to nerve root compression by the tumour or secondary to vertebral collapse. It is important however to bear in mind that patients might present with backache totally unrelated to MSCC and some patients with MSCC experience no backache (Box 1).

Box 1. When to think of metastatic spinal cord compression.

| Low index of suspicion | High index of suspicion |

|---|---|

|

|

Usually the progression to sensori-motor deficits and bladder and bowel dysfunction occurs slowly. Heaviness or clumsiness of limbs may be an early sign of motor deficits. Sensory deficits include anaesthesia, hyperaesthesia, or paraesthesia in the involved dermatomes. Autonomic dysfunction with bowel and bladder problems is associated with a poorer prognosis and irreversibility of functional recovery.

In patients with undiagnosed cancers, using detailed history taking and physical examination coupled with awareness of red flags would increase chances of detection of suspected cases of MSCC. One needs to explore other cancer symptoms such as anorexia, weight loss, lymphadenopathy, cough, and bowel and bladder symptoms.

Physical examination findings may vary from isolated spinal tenderness with no definite neurology to hard neurological signs with deficits.

PATIENT EDUCATION

Significant efforts are needed to educate patients and carers about MSCC. This can be achieved effectively by an MSCC card which can be given to patients with diagnosed cancers to highlight the key symptoms and local contacts available (Box 2).

Box 2. Stop Cancer Disability — Think Spine (front and back of specimen MSCC card).

Cancer may rarely spread to the spine and compress the spinal cord and nerves. It is important to be aware of this condition as the earlier it is treated the better will be the final outcome.

Symptoms to look out for:

Back pain which is new, in a specific area, severe or different from your usual pain.

Back pain spreading to the front of the chest like a band.

Difficulty in walking.

Pins and needles or numbness in upper or lower limbs.

If any of the symptoms mentioned on the front of the card are present contact:

Hospital team, GP or Nurse within 24 hours.

If unable to contact anyone go to nearest A&E.

Tell the health professional that you have cancer and are worried about your spine.

Contact them urgently if you have the following symptoms:

Problems controlling bowels or bladder

Progressive weakness of legs

Increasing numbness and heaviness of arms or legs.

MANAGEMENT

Referral

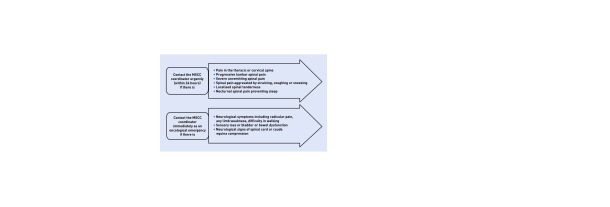

As per the NICE guidelines, every cancer network should be setting up an MSCC coordinator (Figure 1). They would be the point of contact for every suspected MSCC and through whom the referrals would be routed.4

Figure 1.

Referral.

Investigation

Plain radiographs are often used in general practice to evaluate new-onset backache. However, it is a poor screening test and identifies only advanced cases with vertebral collapse and pathological fractures.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the gold-standard investigation in MSCC. NICE guidelines state that MRI should be done early (within 24 hours if a high index of suspicion) so that definite treatment can be planned within a week. Computed tomography (CT) scans with or without three-dimensional reconstruction complement MRI and help operative planning. Bone scans can screen the entire skeleton and give an overall picture of bone involvement. However, they may miss para-spinal tumours with epidural extensions.

TREATMENT

A multidisciplinary team approach is followed with involvement of the spinal surgical team, oncologist, and radiologist. There is also an important role for the palliative care and allied healthcare professionals, with paramount emphasis on patient preference. The aim of the treatment is not curative. The major goals are pain control and preservation of function with a better quality of life for the patient.

Treatment options are broadly surgery and radiotherapy. There is a definite role for commencing steroids in the patients with suspected MSCC to reduce oedema and prevent further injury to the cord.

Surgery

Surgery is preferred in the presence of spinal instability and neurological signs in patients who have a moderate to good prognosis. Surgical treatments could involve simple spinal decompression, spinal stabilisation procedures, or both. Vertebroplasty or kyphoplasty could also be considered in a specific subset of patients for pain relief and to prevent further collapse of the vertebrae.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy could be initiated in isolation for poor surgical candidates or non-surgical candidates. It is also used as an adjunctive therapy in patients who undergo surgery as treatment of the spinal metastases. NICE recommends palliative single-fraction radiotherapy even to patients who have a poor prognosis of possible pain relief.

Research evidence suggests that early detection and surgical treatment could be more effective than radiotherapy alone in maintaining mobility in a select subset of patients affected by MSCC.

CONCLUSION

With the continued growth of the older population and improvements in cancer therapies, the number of patients with symptomatic spinal metastases are likely to increase. As most of these patients will be managed in the community they are more likely to present first to their GPs. It is said that ‘the eyes cannot see what the mind doesn’t know’. Knowledge of the presentation, suspicion of the condition, and awareness of referral pathways are essential for better and prompt management of this condition and to prevent disability.

Provenance

Freely submitted; not externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: www.bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.Bach F, Larsen BH, Rohde K, et al. Metastatic spinal cord compression. Occurrence, symptoms, clinical presentations and prognosis in 398 patients with spinal cord compression. Acta Neurochir. 1990;107(1–2):37–43. doi: 10.1007/BF01402610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Husband DJ. Malignant spinal cord compression: prospective study of delays in referral and treatment. BMJ. 1998;317(7150):18–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7150.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiff D, O’Neill BP, Suman V. Spinal epidural metastasis as the initial manifestation of malignancy: clinical features and diagnostic approach. Neurology. 1997;49(2):452–456. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.2.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Metastatic spinal cord compression: Diagnosis and management of adults at risk of and with metastatic spinal cord compression N ICE guidelines (CG75) London: NICE; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]