Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most important opportunistic bacteria, causing a wide variety of infections particularly in immunocompromised patients. The extracellular glycocalyx is produced in copious amounts by mucoid strains of P. aeruginosa. Mucoid and non-mucoid P. aeruginosa strains show some differences in their antimicrobial susceptibility pattern. The aim of this study was to investigate the frequency of mucoid and non-mucoid types and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns isolated from Milad and Mostafa Khomeini Hospital in Tehran, Iran.

One hundred P. aeruginosa isolates were collected which all were confirmed by conventional biochemical tests and PCR assay using specific primers for oprI and oprL lipoproteins. Mucoid and non-mucoid types of isolates were determined by culturing isolates on BHI agar containing Congo red and Muir mordant staining method. The susceptibility pattern of isolates against 23 different antibiotics was assessed using MIC sensititre susceptibility plates.

Fifty of 100 of isolates were mucoid type, of which 14 isolates were from Mostafa Khomeini Hospital. Frequency of mucoid type of P. aeruginosa in Mostafa Khomeini hospital (70%) was higher than that seen in Milad hospital (45%). The statistical analysis of MICs results showed significant differences in antimicrobial resistance among mucoid and non-mucoid types (non mucoid strains showed more resistance against tested antibiotics). This may be due to the tendency of some antibiotics to attach to extracellular glycocalyx of mucoid strains.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, mucoid/non-mucoid, antimicrobial susceptibility

Zusammenfassung

Pseudomonas aeruginosa ist eines der wichtigsten opportunistischen Bakterien, das vor allem bei immunsupprimierten Patienten eine Vielzahl von Infektionen verursacht. Die extrazelluläre Glycocalyx wird von Mukoid bildenden P. aeruginosa-Stämmen in großer Menge gebildet. Mukoid und nicht Mukoid bildende P. aeruginosa-Stämme zeigen einige Unterschiede in ihrer antimikrobiellen Empfindlichkeit. Daher sollte die Häufigkeit Mukoid und nicht Mukoid bildender Isolate und deren antimikrobielle Empfindlichkeit im Milad und Mostafa Khomeini Hospital in Teheran, Iran, analysiert werden.

Es wurden 100 P. aeruginosa-Isolate gesammelt und biochemisch sowie mittels PCR (spezifische Primer für oprI und oprL Lipoproteine) bestätigt. Mukoid und nicht Mukoid bildende Isolate wurden durch Kultivierung auf BHI-Agar mit Kongorot und Färbung nach Muir bestimmt. Die MIC wurde gegen 23 Antibiotika ermittelt.

50 der 100 Isolate bildeten Mukoid, davon 14 aus dem Mostafa Khomeini Hospital. Die Häufigkeit der Mukoid-Bildner war im Mostafa Khomeini Hospital mit 70% höher als im Milad Hospital (45%). Die nicht Mukoid bildenden Isolate erwiesen sich als signifikant resistenter gegen die getesteten Antibiotika. Eine Ursache hierfür könnte die Tendenz mancher Antibiotika zum Attachment an die extrazelluläre Glycocalyx Mukoid bildender Stämme sein.

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most common pathogens causing nosocomial infection with the high mortality rate [1], [2], [3]. The intrinsic resistance of P. aeruginosa to numerous antimicrobial agents and notable increasing of multi-drug resistance strains play an important role in high mortality rate in nosocomial infection [4], [5]. Moreover, it was shown that P. aeruginosa is an important pathogen causing severe infections in patients suffering from respiratory diseases, chemotherapy cancer patients, immunocompromised hosts and young adults with cystic fibrosis [6], [7], [8], [9]. P. aeruginosa is a highly adaptable microorganism and can develop resistance to different antibiotics. Multidrug-resistance (MDR) strains of P. aeruginosa use different mechanisms for developing resistance such as producing enzymes for inactivating β-lactams like ESBL (extended spectrum beta lactamase), MBL (metallo-β-lactamase) [10], [11], and biofilm formation can enhance ability of resistance in P. aeruginosa [12]. P. aeruginosa isolated from respiratory tract with typical non-mucoid phenotype, but in prolonged infection, can shift to mucoid form with producing large amounts of exopolysaccharide called alginate [13], [14]. Overexpression of alginate in mucoid strains forming micro-colonies which may be less susceptible to host defense mechanisms [15]. Mutation may induce mucoid variants, emerging within months of colonization. Thus, transition from early colonization to chronic infection may be associated with a change in P. aeruginosa phenotype from non-mucoid to mucoid colony formation [16]. The antimicrobial susceptibility pattern is different between mucoid and non-mucoid P. aeruginosa strains. It was suggested that biofilm formation of P. aeruginosa strains are more resistant to antibiotics; initially this resistance was related to mucoid strains. One hypothesis has been that glycocalyx can act like a major barrier to antibiotic diffusion because of its polyanionic characteristics [17], [18]. This hypothesis was refuted by the fact that some antibiotics such as tobramycin can bind to exopolysaccharide produced by P. aeruginosa [19].

The aim of this study was to determine the phenotypic type (mucoid/non-mucoid) of P. aeruginosa isolated from hospitalized patients in Milad and Mostafa Khomeini Hospitals in Tehran, Iran and to investigate the differences in antimicrobial susceptibility pattern among mucoid and non-mucoid isolates.

Materials and methods

One hundred P. aeruginosa were collected from two hospitals in Tehran. Eighty P. aeruginosa were isolated from hospitalized patients in Milad Hospital and 20 strains from patients referred to Mostafa Khomeini Hospital.

Biochemical and molecular identification of bacterial strains

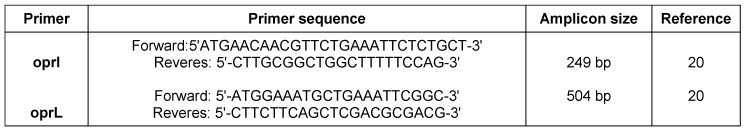

Initial biochemical tests were performed to characterize P. aeruginosa such as growth on MacConkey agar medium, oxidase, catalase, urease, Sulfur Indole Motility test (SIM), triple sugar iron agar, oxidation/fermentation glucose, lysine decarboxylase, methyl red and Voges-Proskauer (MR-VP), Simmon citrate test, gelatin hydrolysis and growth at 42°C. The identity of isolates was confirmed using two specific sets of primers which amplify two outer membrane lipoproteins as described elsewhere [20]. PCR amplification of I lipoprotein (oprl) was performed for detection of genus and L lipoprotein (oprL) for detection of species of this organism. The sequences of primers are shown in Table 1 (Tab. 1). Bacterial DNA extraction was performed using boiling method and extracts of genomic DNA were subjected to PCR assay. PCR was performed in a reaction mixture with the total volume of 25 Il, containing 5 Il template DNA (20 ng), 2.5 Il 10X Taq polymerase buffer [100 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.3), 500 mM KCl, and 15 mM MgCl2], 0.25 Il (100 pmol/ Il) each of primers, 0.25 Il dNTPs (10 mM), 0.2 Il (5U/ Il) Taq DNA polymerase and 16.55 Il sterilized distilled water. Amplification for oprI and oprL was done as follows: initial denaturation step at 93°C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles consisting of denaturation (93°C for 1 min), annealing (57°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 1 min), followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min.

Table 1. Primer sequences.

Differentiation of mucoid and non-mucoid strains

Mucoid strains were identified using the Muir method as described elsewhere [21]. Briefly, for each of 100 isolates, a thin film of suspension was prepared and air-dried, the film was covered with a piece of filter paper and slide was flooded with Ziehl-Neelsen carbol fuchsin and heated to steaming for 30 seconds. The slide was gently rinsed with 95% ethanol and then with distilled water. Mordant solution was added for 20 seconds and then washed with distilled water followed by de-colorization step using ethanol. For counterstaining, 0.3% methylene blue was used for 30–60 seconds prior to examination of the preparations under the oil immersion lens. The cells were stained red, and the capsules blue.

Determination of biofilm formation by Congo red agar method (CRA)

Biofilm formation was determined by the CRA method described elsewhere [22]. BHI agar medium was prepared and supplemented with 5% sucrose and 0.08% Congo red (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). Congo red was prepared in form of concentrated aqueous solution and it was autoclaved at 121°C for 15 min, separately from other medium constituents. Following autoclave, the concentrated solution was added to agar which was previously cooled to 55°C. All 100 isolates were cultivated in streaks on prepared BHI agar medium and incubated aerobically at 37°C for 24–48 h.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for 23 different antibiotics was performed for all 100 isolates using MIC sensititre susceptibility plates (TREK Diagnostic Systems, Cleveland, OH) according to instruction provided by the manufacturer. The bacterial suspension of isolates with final concentration of 105 CFU/ml was prepared and followed by manufacturer’s instruction.

Statistical analysis

The MICs of all tested antibiotics for mucoid and non-mucoid isolates were analyzed using SPSS software, version 17.0. The chi square of all antibiotics was determined between mucoid and non-mucoid isolates and p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Identification of isolates

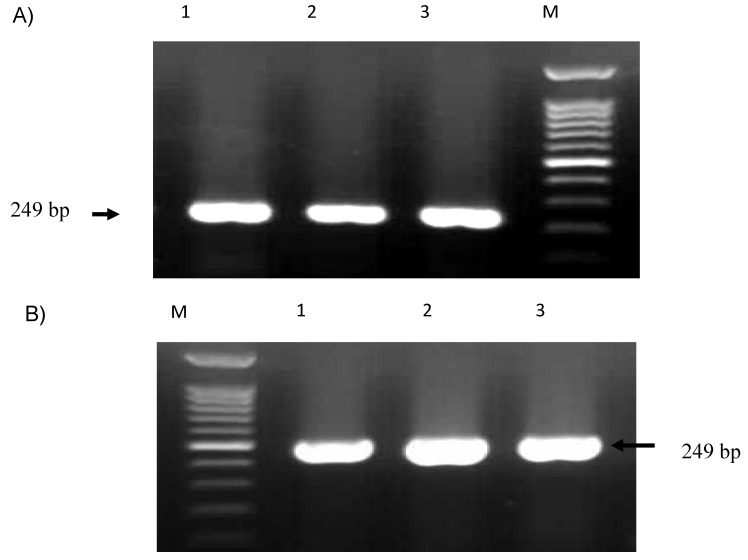

One hundred isolates with yellow colonies on MacConkey agar medium, lactose –, oxidase +, Simmon citrate +, urease –, TSI (Alk/Alk), lysine decarboxylase –, oxidation of glucose +, MR –, VP –, gelatin hydrolysis + and growth on 42°C + were identified as P. aeruginosa. PCR assay confirmed the identification of isolates. Specific 249 and 504 bp bands were detected in all isolates which were corresponded to oprI and oprL gene and determine the Pseudomonas genus and P. aeruginosa, respectively (Figure 1 (Fig. 1)).

Figure 1. A) PCR amplification of oprI gene among suspected isolates for detection of Pseudomonas spp. M: 1kb DNA size marker; lane1: positive control P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853; lane; 2,3: suspected isolates.

B) PCR amplification of oprL gene among suspected isolates for detection of P. aeruginosa. M: 1kb DNA size marker; lane1: positive control P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853; lane; 2–3 suspected isolates.

Differentiation between mucoid and non-mucoid isolates

Phenotypic determination of mucoid and non-mucoid isolates was investigated by two phenotypic method, Muir mordant staining and Congo red agar assay. Half of the isolates (50%) were mucoid and 50% were non-mucoid. The mucoid strains showed red colonies and non-mucoid produced pink to white colonies on BHI agar containing Congo red and sucrose. Fourteen of 20 (70%) strains isolated from Mostafa Khomeini Hospital and 36 of 80 (45%) strains isolated from Milad Hospital were mucoid.

Antimicrobial susceptibility among mucoid and non-mucoid isolates

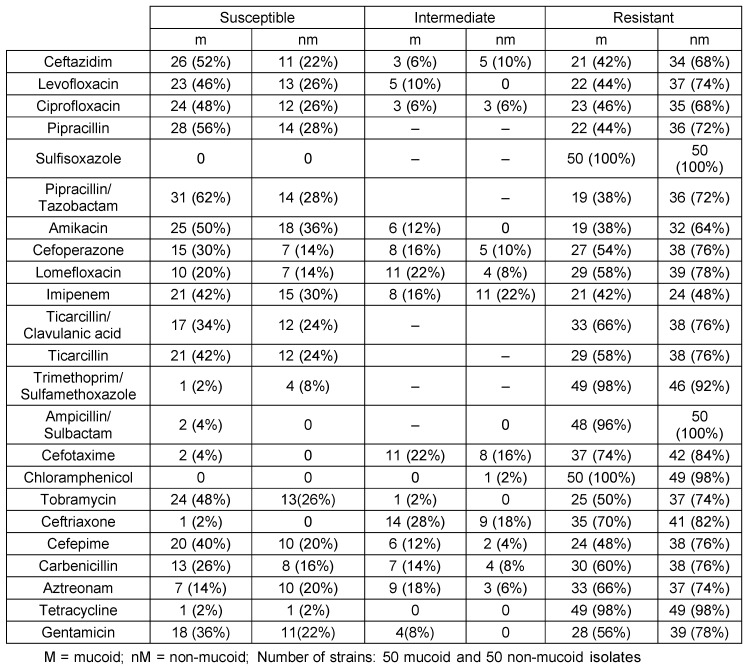

Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of mucoid and non-mucoid P. aeruginosa against 23 different tested antibiotics was determined (Table 2 (Tab. 2)). Among mucoid isolates, high resistance corresponded to sulfisoxazole (100%), chloramphenicol (100%), co-trimoxazole (98%), tetracycline (98%) and ampicillin/sulbactam (96%). Whereas high resistance rate among non-mucoid isolates was seen in sulfisoxazole (100%), ampicillin/sulbactam (100%), co-trimoxazole (92%), cefotaxime (84%), chloramphenicol (98%), ceftriaxone (82%) and tetracycline (98%).

Table 2. Susceptibility pattern of P. aeruginosa isolate to different antibiotics (Number of strains (%)).

Statistical analysis of susceptibility patterns of mucoid and non-mucoid isolates

Statistical analysis showed that non-mucoid isolates were significantly more resistant than mucoid type to β-lactams, aminoglycosides (such as amikacin, tobramycin and gentamicin) and quinolones (i.e., levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin) (p<0.05). While no significant difference was observed among mucoid and non-mucoid strains in resistance to other tested antibiotics (p>0.05).

Discussion

P. aeruginosa infection is a serious cause of nosocomial infection. This organism is adapted by forming biofilms in which the bacteria are protected from host defenses and antibiotics [23]. For instance, biofilm formation of mucoid P. aeruginosa strains is the main cause of lung infections in patients with cystic fibrosis. The results of this study indicated that amount of mucoid strains have been increased recently in Iran in contrast to previous studies [24]. According to previous studies it was thought that antimicrobial susceptibility patterns are different between mucoid and non-mucoid P. aeruginosa strains [6], [25], [26]. The results of this study showed that mucoid isolates were more susceptible to antibiotics which is consistent with findings of other studies from United States, Thailand [6], [26], [27].

One hypothesis suggests that the glycocalyx material itself usually acts as a polyanionic polysaccharide barrier to antibiotic diffusion [17], [18]. This was refuted by the fact that, although some antibiotics such as tobramycin binds to the exopolysaccharide produced by P. aeruginosa, the resulting reduction in diffusion coefficient of tobramycin within a colony or biofilm would not be enough to allow one to define the glycocalyx as a significant penetration barrier [28]. In the present study, 50% of P. aeruginosa isolates were identified as mucoid type. These findings showed the significant increase in mucoid form of P. aeruginosa in comparison with other studies in Iran (32%) and Thailand (3.6%) [6], [24]. The differences between antimicrobial susceptibility pattern among mucoid and non-mucoid types were more significant in β-lactams antibiotics (i.e. ceftazidime, piperacillin, cefoperazone, ticarcillin, cefepime and carbenicillin (p<0.05). However, in other β-lactams (i.e., cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, aztreonam and imipenem) no significant differences were observed. The higher resistance to β-lactams among non-mucoid strains seen in this study is consistent with Ciofu et al. [29]. In Ciofu study, it was reported that non-mucoid isolates have more ability to produce β-lactamase and are exposed to a relatively higher antibiotic selective pressure than the mucoid type. This might be due to biofilm formation. The biofilm-embedded cells may have different antimicrobial susceptibility pattern depending on the site where each individual bacterial cell is located within the multiple layer of biofilm [30]. The β-lactamase produced by the superficial layer in the biofilm and will be able to inactive the β-lactam before reaching into the deep layers [31]. Mucoid and non-mucoid phenotypes can live in symbiosis within the biofilm. While the mucoid, alginate hyper-producing cells ensure the survival of the biofim, the non-mucoid cells might play protective role against antibiotics.

Resistance to quinolones and aminoglycosides was significant higher in non-mucoid P. aeruginosa isolates than mucoid types. There was no significant difference in resistance to tetracycline, chloramphenicol and cotrimoxazole among mucoid and non-mucoid isolates.

In summary, our findings show the mucoid isolates were generally more susceptible to antibiotics than non-mucoid P. aeruginosa. Regarding the importance of mucoid isolates in nosocomial infections among hospitalized patients specially patients with cystic fibrosis, differentiation between mucoid and non-mucoid isolates may play a major role in the prevention of nosocomial infections. The antimicrobial susceptibility pattern was significantly different between mucoid and non-mucoid P. aeruginosa isolates; these findings could enhance accurate diagnosis and proper antibiotic treatment in nosocomial infection cases. On the other hand, different antibiotic resistance patterns observed in this study could be association with different origin of these isolates which would require further investigation.

Notes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by a grant (M/T 91-01-134-17149) from Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. The authors would like to thank Ms. Bastanshenas for her assistance.

References

- 1.Poole K. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: resistance to the max. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:65. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00065. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2011.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alaghehbandan R, Azimi L, Rastegar Lari A. Nosocomial infections among burn patients in Teheran, Iran: a decade later. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2012 Mar;25(1):3–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azimi L, Motevallian A, Ebrahimzadeh Namvar A, Asghari B, Lari AR. Nosocomial infections in burned patients in motahari hospital, tehran, iran. Dermatol Res Pract. 2011;2011:436952. doi: 10.1155/2011/436952. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2011/436952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambert ML, Suetens C, Savey A, Palomar M, Hiesmayr M, Morales I, Agodi A, Frank U, Mertens K, Schumacher M, Wolkewitz M. Clinical outcomes of health-care-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance in patients admitted to European intensive-care units: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011 Jan;11(1):30–38. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70258-9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahar P, Padiglione AA, Cleland H, Paul E, Hinrichs M, Wasiak J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemia in burns patients: Risk factors and outcomes. Burns. 2010 Dec;36(8):1228–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2010.05.009. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srifuengfung S, Tiensasitorn C, Yungyuen T, Dhiraputra C. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mucoid and non-mucoid type. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2004 Dec;35(4):893–896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmeli Y, Troillet N, Eliopoulos GM, Samore MH. Emergence of antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: comparison of risks associated with different antipseudomonal agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999 Jun;43(6):1379–1382. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.6.1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambert PA. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J R Soc Med. 2002;95 Suppl 41:22–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saderi H, Karimi Z, Owlia P, Bahar MA, Akhavi Rad SMB. Phenotypic detection of Metallo-beta-Lactamase producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains isolated from burned patients. Iran J Pathol. 2008;3(1):20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moya B, Dötsch A, Juan C, Blázquez J, Zamorano L, Haussler S, Oliver A. Beta-lactam resistance response triggered by inactivation of a nonessential penicillin-binding protein. PLoS Pathog. 2009 Mar;5(3):e1000353. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000353. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1000353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borgianni L, Prandi S, Salden L, Santella G, Hanson ND, Rossolini GM, Docquier JD. Genetic context and biochemical characterization of the IMP-18 metallo-beta-lactamase identified in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolate from the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011 Jan;55(1):140–145. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00858-10. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00858-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drenkard E, Ausubel FM. Pseudomonas biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance are linked to phenotypic variation. Nature. 2002 Apr 18;416(6882):740–743. doi: 10.1038/416740a. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/416740a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Govan JR, Harris GS. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and cystic fibrosis: unusual bacterial adaptation and pathogenesis. Microbiol Sci. 1986 Oct;3(10):302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hall MN, Silhavy TJ. Genetic analysis of the ompB locus in Escherichia coli K-12. J Mol Biol. 1981 Sep 5;151(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90218-7. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-2836(81)90218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam J, Chan R, Lam K, Costerton JW. Production of mucoid microcolonies by Pseudomonas aeruginosa within infected lungs in cystic fibrosis. Infect Immun. 1980 May;28(2):546–556. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.2.546-556.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mathee K, Ciofu O, Sternberg C, Lindum PW, Campbell JI, Jensen P, Johnsen AH, Givskov M, Ohman DE, Molin S, Høiby N, Kharazmi A. Mucoid conversion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by hydrogen peroxide: a mechanism for virulence activation in the cystic fibrosis lung. Microbiology. 1999 Jun;145(6):1349–1357. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1349. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/13500872-145-6-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slack MP, Nichols WW. Antibiotic penetration through bacterial capsules and exopolysaccharides. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1982 Nov;10(5):368–372. doi: 10.1093/jac/10.5.368. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jac/10.5.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costerton JW, Irvin RT, Cheng KJ. The bacterial glycocalyx in nature and disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1981;35:299–324. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.35.100181.001503. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.mi.35.100181.001503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeVries CA, Ohman DE. Mucoid-to-nonmucoid conversion in alginate-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa often results from spontaneous mutations in algT, encoding a putative alternate sigma factor, and shows evidence for autoregulation. J Bacteriol. 1994 Nov;176(21):6677–6687. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6677-6687.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Vos D, Lim A, Jr, Pirnay JP, Struelens M, Vandenvelde C, Duinslaeger L, Vanderkelen A, Cornelis P. Direct detection and identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in clinical samples such as skin biopsy specimens and expectorations by multiplex PCR based on two outer membrane lipoprotein genes, oprI and oprL. J Clin Microbiol. 1997 Jun;35(6):1295–1299. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1295-1299.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baron EJ, Finegold SM. Bailey and Scott's Diagnostic Microbiology. 8th ed. New York: Mosby; 1990. pp. 37–38. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atiyeh BS, Costagliola M, Hayek SN, Dibo SA. Effect of silver on burn wound infection control and healing: review of the literature. Burns. 2007 Mar;33(2):139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2006.06.010. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Govan JR, Harris GS. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and cystic fibrosis: unusual bacterial adaptation and pathogenesis. Microbiol Sci. 1986 Oct;3(10):302–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahangarzadeh-Rezaee M, Behzadiyan-Nejad Q, Najjar-Pirayeh S, Owlia P. Higher aminoglycoside resistance in mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa than in nonmucoid strains. Arch Iran Med. 2002;5(2):108–111. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahangarzadeh-Rezaee M, Behzadiyan-Nejad Q, Owlia P, Najjar-Pirayeh S. In vitro activity of imipenem and ceftazidime against mucoid and non-mucoid strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from patients in iran. Arch Iran Med. 2002;5(4):251–254. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shawar RM, MacLeod DL, Garber RL, Burns JL, Stapp JR, Clausen CR, Tanaka SK. Activities of tobramycin and six other antibiotics against Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from patients with cystic fibrosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999 Dec;43(12):2877–2880. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burns JL, Saiman L, Whittier S, Larone D, Krzewinski J, Liu Z, Marshall SA, Jones RN. Comparison of agar diffusion methodologies for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. J Clin Microbiol. 2000 May;38(5):1818–1822. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.1818-1822.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nichols WW, Dorrington SM, Slack MP, Walmsley HL. Inhibition of tobramycin diffusion by binding to alginate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988 Apr;32(4):518–523. doi: 10.1128/AAC.32.4.518. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.32.4.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ciofu O, Fussing V, Bagge N, Koch C, Høiby N. Characterization of paired mucoid/non-mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Danish cystic fibrosis patients: antibiotic resistance, beta-lactamase activity and RiboPrinting. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001 Sep;48(3):391–396. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.3.391. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jac/48.3.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anwar H, Strap JL, Costerton JW. Establishment of aging biofilms: possible mechanism of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992 Jul;36(7):1347–1351. doi: 10.1128/AAC.36.7.1347. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.36.7.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dibdin GH, Assinder SJ, Nichols WW, Lambert PA. Mathematical model of beta-lactam penetration into a biofilm of Pseudomonas aeruginosa while undergoing simultaneous inactivation by released beta-lactamases. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1996 Nov;38(5):757–769. doi: 10.1093/jac/38.5.757. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jac/38.5.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]