Abstract

Background

Findings from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) genome-wide association studies are being translated clinically into prognostic and diagnostic indicators of disease. Yet, patient perception and understanding of these tests and their applicability to providing risk information is unclear. The goal of this study was to determine, using hypothetical scenarios, whether patients with IBD perceive genetic testing to be useful for risk assessment, whether genetic test results impact perceived control, and whether low genetic literacy may be a barrier to patient understanding of these tests.

Methods

Two hundred fifty seven patients with IBD from the Johns Hopkins gastroenterology clinics were randomized to receive a vignette depicting either a genetic testing scenario or a standard blood testing scenario. Participants were asked questions about the vignette and responses were compared between groups.

Results

Perceptions of test utility for risk assessment were higher among participants responding to the genetic vignette (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in perceptions of control over IBD after hypothetical testing between vignettes (P = 0.24). Participant responses were modified by genetic literacy, measured using a scale developed for this study. Participants randomized to the genetic vignette who scored higher on the genetic literacy scale perceived greater utility of testing for risk assessment (P = 0.008) and more control after testing (P = 0.02).

Conclusions

Patients with IBD perceive utility in genetic testing for providing information relevant to family members, and this appreciation is promoted by genetic literacy. Low genetic literacy among patients poses a potential threat to effective translation of genetic and genomic tests.

Keywords: genetic literacy, genetic testing, IBD

Genomics, and more specifically genome-wide association studies, have produced an abundance of data about genetic variants associated with the development of inflammatory bowel diseases, revealing over 150 genetic variants associated with IBD.1–3 These studies have provided significant insights into molecular pathways contributing to the pathogenesis of disease and potential intervention targets for the treatment of IBD. It remains to be seen, however, how genetic information will be integrated into the clinical care of patients, what the barriers to successful integration might be, and whether genetic testing will be able to live up to the high degree of enthusiasm documented in previous studies.4,5 Recently, 2 new tests have been introduced for use in the diagnosis and care of patients with IBD: a 17-marker diagnostic test for IBD that contains 4 genetic markers for disease and a 3-marker prognostic test for Crohn's disease that evaluates risk variants in the NOD2/CARD15 gene.6 In addition to the existing questions about the clinical utility of these tests,7,8 the increasing complexity associated with multi-marker testing for IBD presents challenges to patient interpretation.

Patient understanding of genetic test results, whether those results are interpreted by a clinician or by the patient, may be especially challenging for patients with limited genetic literacy. In this context, genetic literacy incorporates both the ability to decode scientific terminology specific to genetics and a familiarity with genetics terms. Previous studies of attitudes toward genetic testing in IBD populations have indicated that most patients believe that genetic testing will be useful for informing familial risk.5,9 However, focus group data have revealed confusion about the complex etiology of IBD and the implications of genetic testing for patients with IBD and their family members.9 Most patients endorse genetic testing as a way to avoid invasive procedures, optimize therapy, and predict future complications; just over half of those surveyed anticipate that genetic testing will make their IBD feel more treatable or help them feel more prepared.5 It remains unclear how patients with IBD perceive genetic testing to be different from other types of diagnostic and prognostic test information and what role previous understanding of genetics plays in these perceptions.

Research into the role of genetic literacy in facilitating the delivery of genetic tests is limited. Erby et al developed a screening measure of adult literacy, modeled after the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM),10 but composed of genetic terms that were found to be frequently used in over 150 routine cancer and prenatal genetic counseling sessions.11 The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Genetics (REAL-G) is administered by asking subjects to read the list of terms, arrayed by word complexity, to score decoding fluency. The score was predictive of subjects' ability to recall communicated information during simulated genetic counseling sessions among a sample of study participants with limited educational exposure. Participants who scored at the equivalent of a sixth grade level or above on the REAL-G were able to recall significantly more communicated information during a simulated genetic counseling sessions relative to those scoring below this level. The REAL-G has also been used in the context of genetic testing for diabetes risk to show that individuals with low literacy may be at risk to overestimate the impact of low penetrance genetic results.12

Literacy screening measures based on decoding, including the REAL-G, have been most useful in populations with limited educational exposure, such as those who have only completed primary and secondary school grades. The utility of going beyond decoding to capture the degree to which familiarity and comprehension of genetic terms and concepts may be a relevant marker of literacy for individuals with postsecondary education has not been addressed.

Along with the increasing use of genetic tests, we can anticipate that the unfamiliar language and concepts will present difficulty for many patients, even those who would otherwise be considered literate based on existing screening tests. For these patients, relevant information may not be understood or discussed later with care providers or family members, further exacerbating existing health disparities between those of high and low literacy.

In this study, we used a randomized vignette approach to compare hypothetical genetic testing to standard clinical testing with the aim of assessing patients' perceptions of test utility for risk assessment and perceptions of control after hypothetical testing. We also assessed the impact of genetic literacy, measured as familiarity with genetic words and concepts, on those perceptions. We hypothesized that genetic literacy would moderate patients' perceptions of the vignettes.

Methods

Study Population and Randomization

Participants were patients who were actively attending or had previously attended the Johns Hopkins IBD clinic with an indication of inflammatory bowel disease (including all subclassifications of IBD), spoke English, and were older than 18 years. Participants were recruited using a mailing list of IBD clinic patients or directly while at the clinic. From July 2008 to October 2008, participants visiting a Johns Hopkins IBD clinic for physician appointments and/or infusion treatments were approached for the study. Patients who agreed to take the survey in the clinic were given the option of completing it at home and mailing it in. In October 2008, the clinic staff mailed the survey to all patients on the clinical patient mailing list. We were not able to collect data about nonresponders. The surveys were randomized, using a random number generator, in blocks of 10 to contain 1 of the 2 vignettes portraying the delivery of either a positive genetic test result or a positive blood test result.

Measures

Vignette Version

The primary independent variable of this study is the vignette version, referred to as “genetic test” or “standard test.” We randomized the distribution of the genetic testing vignette with a standard blood test vignette so that effects specific to genetic testing not generally applicable to all testing scenarios could be identified. The vignettes were gender matched to the gender of the participant to portray either Michael or Michelle, a patient with IBD who was offered either a genetic test or a standard blood test. The content of the vignette was as follows (randomized text in italics):

“Michelle was referred to a specialty clinic in gastroenterology. She went to her family doctor with concerns about her health, as she had been experiencing frequent diarrhea and abdominal pain for a period of time. She feared that the symptoms were increasingly getting in the way of her job, family life and social life. After initial testing, her doctor diagnosed her with Inflammatory Bowel Disease, and suggested she see a specialist for further testing. One of the tests she was offered by the specialist was a [genetic test to determine if she has a specific version of a gene which placed her at increased risk of having Inflammatory Bowel Disease/blood test to look for the presence of specific types of cells in the blood]. She had her blood drawn for the test and, in her next visit with the specialist was told [that she did inherit a specific version of the gene/that she tested positive and that the specific inflammatory cells were found to be present in her blood]. In the future, this test may help determine which treatments Michelle will receive and provide information about how the disease will likely progress over time. At present, however, this test result doesn't change management of patients with IBD.”

Genetic Literacy

The Genetic Literacy and Comprehension (GLAC) measure (See Supporting Material, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/IBD/A469) was designed for this study to assess familiarity with common genetic terms and concepts in a print survey format. This measure assessed participants' familiarity with 8 commonly used genetic words and concepts: Genetic, Chromosome, Susceptibility, Mutation, Variation, Abnormality, Heredity, and Sporadic using a 7-point scale, ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree with the statement “I am familiar with this term.” Participants also completed multiple choice fill-in-the blank questions consistent with the Cloze technique for assessing word comprehension.13 The genetic terms used were taken from the 8-word short form the REAL-G, a measure of genetic literacy with established face and predictive validity.14 Z-scores were calculated separately for the familiarity and fill-in-the-blank subscales and then summed together for a combined score (Cronbach's α = 0.89 for the combined score).

Perceived Control over IBD

All participants were asked “In general, how much are you able to control your IBD?” and asked to respond using a 7-point scale ranging from “No Control” to “Complete Control.”15

Social Demographics and Patient Characteristics

We also collected social demographic information including patient age, sex, race, marital status, income, and education. Patients self-reported their diagnosis, whether they were currently symptomatic, they had bowel surgery, the time since diagnosis, the time since symptom onset, and the number of family members they have who have IBD. The number of years undiagnosed was calculated by subtracting the time since diagnosis from the time since the symptom onset.

Outcome Measures

Participants were asked to imagine that they were the person in the vignette and answer questions about the testing experience.

Perceived Utility of the Test for Risk Assessment

Three items were included that prompted the participants to interpret the utility of the test for providing information about the cause of Michael/Michelle's IBD and the implications of the test for providing information for family members. Participants were asked to rank their agreement with these items on a 7-point scale (Cronbach's α = 0.80).

Perceived Control After Testing

Four items were included to assess the anticipated impact of the test result on participant perceptions of control over IBD. These items were adapted from a study of control appraisals in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.16 Participants were asked to rank their agreement with these items on a 7-point scale (Cronbach's α = 0.81).

Statistical Analysis

To assure randomization of social demographics, disease history, and family history variables and identify associations with perceived utility of the test and hypothetical control after testing, we used t tests (with Satterthwaite's approximation for unequal variances when appropriate) and chi-square tests. Linear regression was used to test the main effect of testing vignette on the outcomes of interest, controlling for participants' own perceived control. It was also used to test the effects of genetic literacy on assessments of the vignettes, and the interaction between genetic literacy and survey version.

With 257 participants, this study had 0.80% power to detect a small-to-medium effect size of the randomized intervention (3% of the variance in outcomes explained, P = 0.05, 2 sided) with all covariates expected to explain about 10% of the total variance in the outcome variables.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the National Institutes of Health, National Human Genome Research Institute Institutional Review Board (Protocol Number: 08-HG-N141) and the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board (Protocol Number: NA_00018972). Both reviews approved a waiver of signed informed consent in the interests of protecting the confidentiality of study subjects.

Results

Sample Characteristics

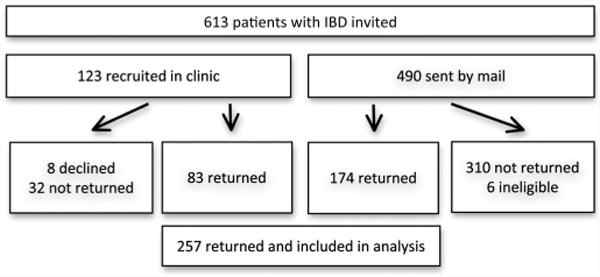

A total of 613 patients were approached either in the clinic (n = 123) or by mail (n = 490) to take the survey (see Fig. 1). Of those thought to be eligible, 41.7% completed the survey. Eight patients approached in the clinic declined to take the survey, and 32 took the survey home but did not return it by mail. Of those who received the survey by mail, 310 did not return the survey and 6 returned the survey but were ineligible because they reported that they had not received a diagnosis of IBD. Potential participants who were given the survey in clinic were significantly more likely to return the survey (67.5% versus 36.0%, P < 0.001) than those who received it by mail.

Figure 1.

Recruitment and study flow.

The demographics of the study patient population are shown in Table 1. Of those completing the survey, the mean age was 48.5 years, 61.1% were female, and 70% of the population had completed a college and/or graduate degree. The disease-related characteristics of the population are presented in Table 2; 63.8% of those completing the survey self-identified as having Crohn's disease and 57.1% reported having symptoms at the time they completed the survey. Participants reported having been diagnosed a mean of 16.9 years before completion of the surveys, and the average time reported from symptoms to diagnosis in this population was 2.5 years. On average, participants had 0.9 family members with IBD. There were no statistically significant differences across any of the demographic or disease-related variables between the randomization groups.

Table 1. Study Population Demographics.

| Total Sample Average (SD) | Genetic Test (n = 144) | Standard Test (n = 113) | t test, p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age, yr | 48.5 (15.04); Range: 18–83 | 48.3 (14.1) | 48.7 (16.3) | 0.83 |

|

| ||||

| Count (%) | Count by version (%) | χ2, p | ||

| Sex | 157 (61.1) | 88 (61.5) | 69 (61.1) | 0.94 |

| Female | ||||

| Race | 238 (93.5) | 134 (96.3) | 104 (90.0) | 0.89 |

| Caucasian | ||||

| Hispanic Origin | 6 (2.3) | 2 (1.4) | 4 (3.5) | 0.25 |

| Marital status | 159 (62.4) | 89 (62.2) | 70 (62.5) | 0.98 |

| Married | ||||

| Income | 175 (70.9) | 103 (74.1) | 72 (66.7) | 0.19 |

| >$70,000 | ||||

| Education | 178 (69.5) | 97 (67.9) | 81 (71.7) | 0.86 |

| College and more | ||||

| Genetic literacy | ||||

| Fill-in-the-blank | 7.1 (1.2) | 7.2 (1.2) | 7.1 (1.3) | 0.34 |

| Familiarity | 5.9 (1.2) | 5.9 (1.2) | 6.0 (1.1) | 0.42 |

Table 2. Patient Disease Characteristics.

| Total Sample (%) | Genetic Test (n = 144) | Standard Test (n = 113) | χ2, p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | 0.36 | |||

| Crohn's disease | 164 (63.8) | 96 (66.7) | 68 (60.2) | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 74 (28.8) | 40 (27.8) | 34 (30.1) | |

| Other | 19 (7.4) | 8 (5.6) | 11 (9.7) | |

| Symptomatic | 144 (57.1) | 76 (54.7) | 68 (60.2) | 0.38 |

| Have had bowel surgery | 109 (42.4) | 65 (45.1) | 44 (38.9) | 0.32 |

| Recruited in clinic | 83 (32.2) | 45 (31.2) | 38 (33.6) | 0.78 |

| Time since diagnosis, mean (SD) | 16.9 (12.6) | 17.9 (12.2) | 15.7 (13.0) | 0.17 |

| Years undiagnosed, mean (SD) | 2.5 (5.3) | 2.5 (4.9) | 2.5 (5.8) | 0.99 |

| Number of family members with IBD, mean (SD) | 0.9 (1.3) | 1.0 (1.4) | 0.8 (1.2) | 0.40 |

Perceived Utility of the Test and Perceived Control After Testing

Participants rated the utility of the hypothetical genetic test more highly than they rated the usefulness of the blood test in understanding: the cause of IBD, whether IBD runs in the family, and if family members are at risk of IBD (for the combined scale, Satterthwaite t(182.7) = −6.21, P < 0.001). Mean scores for both groups fell above the midpoint of the 7-point scale (5.8/7 for the genetic test and 4.7/7 for the standard test) indicating generally positive endorsement for the usefulness of both tests for understanding the cause of IBD and risk to relatives.

There were no significant differences in perceptions of disease control after the hypothetical receipt of test results between those who received the genetic test vignette and those who received the blood test vignette (t(251) = −1.19, P = 0.23). Mean scores were 4.4/7 for the genetic test and 4.2/7 for the standard test.

Genetic Literacy

Mean scores on the GLAC were high (Table 1). We did not detect a significant association with genetic literacy and perceived utility of the test for risk assessment or perceived control after testing. Scores on the GLAC were associated with education (Pearson's r = 0.33, P < 0.001) and income (Pearson's r = 0.17, P = 0.008). Recruitment method was also associated with GLAC scores, such that returning the survey by mail was associated with higher scores (Pearson's r = 0.25, P = 0.003). To account for these discrepancies as potential confounders, education, income, and recruitment methods were included in the multivariate models.

Multivariate Models of Perceptions of Test Utility and Disease Control After Testing

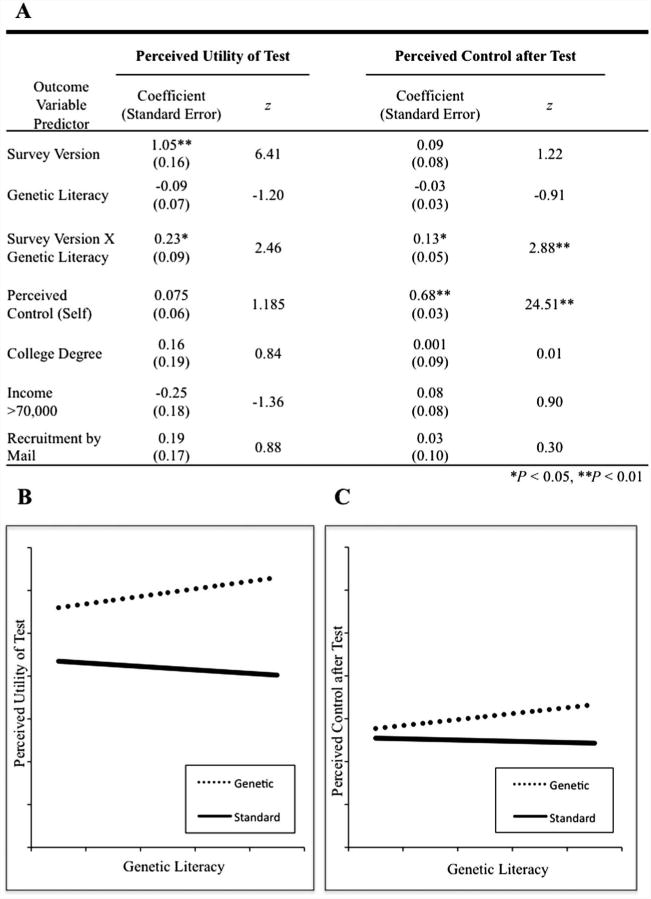

To test the impact of genetic literacy on participant perceptions of the 2 vignettes, we conducted multiple regression analyses controlling for the potential confounders of recruitment method and participant's perception of control over their IBD (Fig. 2). In analyses of perceived test utility for risk assessment, a significant main effect of vignette version was detected (β = 1.00, P < 0.001), indicating that patients perceived the genetic test as more useful for understanding disease etiology and family risks than the standard test. There was no significant main effect of genetic literacy on perceptions of test utility, but a significant interaction between genetic literacy and vignette version was detected (β = 0.26, P = 0.008). This indicates that among those who received the genetic testing scenario, genetic literacy is more positively associated with increased perceptions of test utility for risk assessment than among those who received the standard testing scenario.

Figure 2.

Genetic literacy modifies participant perceptions of testing. A, Regression coefficients for multivariate models of perceived utility of the test for risk assessment and perceived control after testing. B, Plotted regression lines of perceived utility of the test versus genetic literacy, separated by vignette version. C, Plotted regression lines of perceived control after testing versus genetic literacy, separated by vignette version.

In multivariate analyses of disease control after hypothetical testing, we did not detect significant main effects of vignette version or genetic literacy on perceived control after testing. Perceived control over one's own IBD was the strongest predictor of perceived control after hypothetical testing (β = 0.38, P < 0.001). We also found a significant interaction effect between genetic literacy and vignette version (β = 0.17, P = 0.02), such that genetic literacy was associated with increased perceptions of control after hypothetical testing for those who received the genetic testing scenario (Table 3).

Table 3.

Participant Perceptions of Vignette Test Outcome

| Perception of Test Outcome | Genetic Test, Mean (SD) | Standard Test, Mean (SD) | t test, p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived utility of test for risk assessment | 5.8 (1.0) | 4.7 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| This test will help understand why Michael has IBD | 5.2 (1.7) | 4.2 (2.0) | <0.001 |

| This test will help Michael understand if IBD runs in the family | 6.0 (1.2) | 4.8 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| This test will help Michael understand if his family members are at risk for IBD | 6.1 (1.0) | 5.0 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Perceived control after test | 4.4 (1.2) | 4.2 (1.1) | 0.24 |

| In general, how much control will Michael have over his disease? | 3.9 (1.4) | 3.8 (1.4) | 0.55 |

| How much control will he have over his daily symptoms? | 4.0 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.4) | 0.60 |

| How much control will he have over the long-term course of his disease? | 4.4 (1.5) | 4.1 (1.4) | 0.26 |

| How much control will he have over his medical care and treatment? | 5.2 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.5) | 0.13 |

Discussion

Our data suggest that 1) individuals with IBD generally perceived utility in the genetic test for informing them about disease etiology and familial risk and 2) receiving positive genetic test results for IBD was not associated with decreased perceptions of hypothetical disease control relative to the standard blood testing vignette. These findings extend our understanding of patient understanding of genetic testing compared with other standard clinical tests, providing useful insight in considering the clinical integration of genetic tests.

Perceptions of utility for risk assessment and control after testing were moderated by genetic literacy, highlighting the potential vulnerability to misperception or misunderstanding of individuals undergoing testing in the IBD clinic. This vulnerability becomes particularly salient because prognostic and diagnostic tests become increasingly complex and information used for one purpose (e.g., to arrive at a diagnosis or determine prognosis) has additional implications for one's disease (e.g., familial risk and underlying disease etiology). To our knowledge, this is the first study to use a randomized vignette approach to explore perceptions among patients with IBD, incorporating a number of factors associated with improved accuracy in hypothetical genetic testing scenarios.17 We randomized the distribution of the genetic testing vignette with a standard blood testing vignette so that effects specific to genetic testing not generally applicable to all testing scenarios could be identified. This methodology allowed us to gain new insight into patient interpretation of genetic tests compared with other, more standard, types of testing.

Possible Explanations and Comparison with Existing Literature

Perceived Test Utility and Control after Hypothetical Testing

Participants' high endorsement of the utility of the genetic test for providing information about familial risk and disease etiology likely reflects both understanding of the implications of genetic testing and positive attitudes toward genetic testing. Positive attitudes toward hypothetical genetic tests for IBD have been reported previously,4,5,9 but understanding has been largely unexplored. The content of our vignette is a close parallel to the recent trend of genetic tests being offered to patients with IBD clinically for diagnostic and prognostic purposes, with little mention in supporting materials of implications for family members or identifying the underlying cause of the disease. As such, our study provides a timely assessment of the extent to which patients with IBD are able to extrapolate this information in comparison with other types of tests. We were able to address an oft-cited concern about genetic tests (e.g., Brant and McGovern8), namely that such tests could be associated with fatalistic responses and decreased perceptions of control over one's disease. Consistent with other studies conducted among individuals with conditions of complex genetic etiology,18,19 we find no evidence for decreased perceptions of control associated with genetic tests.

Genetic Literacy as a Moderator

Our finding that genetic literacy is associated with perceived utility of testing to inform risks and hypothetical control after testing among those who received the genetic test vignette provides new insight into the potential role of genetic literacy as genetic tests are introduced into clinical practice. Genetic terminology and scientific jargon used in consenting to genetic testing and explaining test results may pose obstacles to understanding and extrapolation of test value and utility. Individuals with lower scores on the GLAC were less likely to perceive the test as useful for providing information for family members and disease etiology. This may reflect decreased understanding of the implications of genetic testing and/or more negative attitudes regarding the usefulness of genetic testing compared with those with higher GLAC scores. The significant interaction effect observed with regard to perceived control after hypothetical genetic testing may reflect increased perceptions of control as a result of having more information about one's disease and its etiology (informational control).20 Of the 4 questions we asked about control, perceived control over medical care and treatment showed the greatest difference between the genetic and the standard blood testing vignette among those with higher genetic literacy scores, implying that this domain of control is most salient. This finding is consistent with the reported 60% of patients with IBD perceiving that genetic testing will make IBD more treatable.5 Alternatively, this result could also be related to the specific wording of the vignette in which participants were told “in the future may help guide treatment and provide prognostic information.”

Health literacy is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions.21 Previous studies assessing genetic literacy have used measures capturing largely the ability to decode and read genetics terms, reflecting an individual's ability to obtain information about genetics. These studies have demonstrated that literacy plays a role in client learning and motivations to act on genetic test results.11,12,22 The GLAC measures familiarity with genetic words and comprehension of related concepts, providing a more nuanced measure of literacy than reflected in widely used literacy screens based solely on decoding fluency. Conceptual literacy is clearly important for adult learning and integration of new knowledge, as adult learning is generally dependent on previous vocabulary, familiarity, and understanding.23 New information is less likely to be integrated by those lacking in conceptual literacy. Given the high levels of education among participants in this study, the GLAC may also capture more meaningful variation. It addresses some of the same barriers related to jargon and technical language identified in earlier studies and presents a novel approach to measuring a construct of increasing clinical relevance in the IBD population and beyond. To date, the implications of conceptual literacy on genetic testing have been largely unexplored.

Limitations

At the time of recruitment, testing was not routinely offered to patients with IBD. The testing described in the vignettes was hypothetical and not yet reflective of actual clinical scenarios. Consequently, we were less concerned with the question of “if people understood the vignette than we were with “how” they understood it. As such, analyses did not include a manipulation check to exclude individuals who did not appropriately grasp the genetic nature of the test in one scenario or the “nongenetic” nature of the test in the other. Interpretations of study results should be made accordingly. We also note as a limitation that although the study groups were equivalent on all measured characteristics, we were unable to address the possibility that differential response rates between groups could have broken randomization in some unmeasured way.

The study sample was exclusively English-speaking and largely Caucasian, of high socioeconomic status, middle-aged, female, and married. Although this is somewhat the characteristic of the tertiary care clinic populations from which we recruited, who may be making decisions about genetic testing, the study sample may limit the generalizability to the broader IBD population. The response rate difference between those attending clinic and those receiving the survey by mail represents another bias. To account for possible differences in literacy as a result of a selection bias among those returning the survey by mail, we controlled for recruitment method, education, and income in multivariate analyses. However, this difference between the recruitment samples limits our ability to completely define the subpopulations within the clinic to whom these results apply.

Finally, our measure of genetic literacy was adapted from a previously validated measure11 found to be useful in populations with low educational attainment and modified for use in this study and its participants. Although the measure demonstrates good internal and face validity, and the scores on the GLAC are positively correlated with education and appropriate extrapolation of information from a vignette, additional external validations and future studies are warranted.

Clinical Implications

The primary outcomes of this study are informative for the delivery of genetic tests in the IBD clinic by clinicians and through the supporting material provided to promote understanding. It is of value to know that, generally, patients with IBD can perceive value to themselves and family members associated with genetic testing. It is also reassuring to note that genetic testing seems unlikely to invoke fatalistic responses and may instead, for some people, increase their perceptions of control over IBD. The results of this study are perhaps most informative for designing educational interventions to support the delivery of genetic test results for IBD because these data highlight the critical importance of recognizing the cognitive burden posed by these new genetic tests and designing clinical interventions accordingly. We show that even in a well-educated clinic population, patients who might be able to decode genetic terminology may still experience barriers to understanding stemming from a lack of word comprehension. These data argue in favor of developing educational materials that are broadly accessible to individuals of varying levels of genetic literacy with varying backgrounds, avoiding overly complex terminology and jargon. In doing so, we may more effectively integrate new technologies and work toward maximizing the potential health benefits of the great investments made in human genome research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Dr. Steven Brant and Dr. Susan Hutfless for their comments on the manuscript and Cris Price of Abt Associates for data analysis support.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Anderson CA, Boucher G, Lees CW, et al. Meta-analysis identifies 29 additional ulcerative colitis risk loci, increasing the number of confirmed associations to 47. Nat Genet. 2011;43:246–252. doi: 10.1038/ng.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franke A, McGovern DP, Barrett JC, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn's disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1118–1125. doi: 10.1038/ng.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–124. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konda V, Huo D, Hermes G, et al. Do patients with inflammatory bowel disease want genetic testing? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:497–502. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200606000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lal S, Appelton J, Mascarenhas J, et al. Attitudes toward genetic testing in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:321–327. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328013e9a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prometheus Therapeutics and Diagnostics. The Synergistic Role of Serology, Genetics, and Inflammation in the Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. San Diego; CA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shirts B, von Roon AC, Tebo AE. The entire predictive value of the prometheus IBD sgi diagnostic product may be due to the three least expensive and most available components. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1760–1761. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brant SR, McGovern DP. NOD2, not yet: con. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:507–509. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000160739.38237.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis JR, Konda V, Rubin DT. Genetic testing for inflammatory bowel disease: focus group analysis of patients and family members. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2009;13:495–503. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2008.0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25:391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erby LH, Roter D, Larson S, et al. The rapid estimate of adult literacy in genetics (REAL-G): a means to assess literacy deficits in the context of genetics. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:174–181. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vassy JL, O'Brien KE, Waxler JL, et al. Impact of literacy and numeracy on motivation for behavior change after diabetes genetic risk testing. Med Decis Making. 2012;32:606–615. doi: 10.1177/0272989X11431608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor WL. “Cloze procedure”: a new tool for measuring readability. Journal Q. 1953;30:415–433. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roter DL, Erby LH, Larson S, et al. Assessing oral literacy demand in genetic counseling dialogue: preliminary test of a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65:1442–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallston KA, Wallston BS, DeVellis R. Development of the multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) scales. Health Educ Monogr. 1978;6:160–170. doi: 10.1177/109019817800600107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Affleck G, Tennen H, Pfeiffer C, et al. Appraisals of control and predictability in adapting to a chronic disease. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53:273–279. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.53.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Persky S, Kaphingst KA, Condit CM, et al. Assessing hypothetical scenario methodology in genetic susceptibility testing analog studies: a quantitative review. Genet Med. 2007;9:727–738. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e318159a344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McBride CM, Koehly LM, Sanderson SC, et al. The behavioral response to personalized genetic information: will genetic risk profiles motivate individuals and families to choose more healthful behaviors? Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:89–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins RE, Wright AJ, Marteau TM. Impact of communicating personalized genetic risk information on perceived control over the risk: a systematic review. Genet Med. 2011;13:273–277. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f710ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olbrisch ME, Ziegler SW. Psychological adjustment to inflammatory bowel disease: informational control and private self-consciousness. J Chronic Dis. 1982;35:573–580. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(82)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portnoy DB, Roter D, Erby LH. The role of numeracy on client knowledge in BRCA genetic counseling. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81:131–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knowles MS. Andragogy in Action. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1984. p. xxiv. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.