Abstract

Purpose of Review

Cardiovascular disease remains the single most serious contributor to mortality in chronic kidney disease (CKD). Although conventional risk factors are prevalent in CKD, both cardiomyopathy and vasculopathy can be caused by pathophysiologic mechanisms specific to the uremic state. CKD is a state of systemic αKlotho deficiency. While the molecular mechanism of action of αKlotho is not well understood, the downstream targets and biologic functions of αKlotho are astonishingly pleiotropic. An emerging body of literature links αKlotho to uremic vasculopathy.

Recent Findings

The expression of αKlotho in the vasculature is controversial due to conflicting data. Regardless of whether αKlotho acts a circulating or resident protein, there are good data associating changes in αKlotho levels with vascular pathology including vascular calcification and in vitro data of direct action of αKlotho on both the endothelium and vascular smooth muscle cells in terms of cytoprotection and prevention of mineralization.

Summary

It is critical to understand the pathogenic role of αKlotho on the integral endothelium-vascular smooth muscle network rather than each cell type in isolation in uremic vasculopathy, as αKlotho can serve as a potential prognostic biomarker and a biological therapeutic agent.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, αKlotho, vascular calcification, vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelium

Introduction

αKlotho was discovered when the serendipitous disruption of its locus led a phenotype of premature multi-organ degeneration and failure [1]. In addition its role as an anti-ageing molecule, the documented downstream actions of αKlotho encompasses an impressively wide range of cell functions including energy metabolism, inhibition of Wnt signaling, antioxidation, modulation of ion transport, and regulation of mineral metabolism [2]. αKlotho is a member of a more extended family of three paralogs (α, β, and γKlotho) but thus far only αKlotho has been shown to exist in the circulation to exert distant effects as an endocrine substance [3■]. Because the kidney is likely the major source of circulating αKlotho, αKlotho is a major regulator of mineral metabolism which is grossly deranged in chronic kidney disease (CKD), and the strikingly similar cardiovascular lesions seen in genetic αKlotho deficiency and CKD, the focus of αKlotho biology has shifted from aging-related to more nephrocentric issues [4, 5]. We will summarize recent findings of the relationship between αKlotho and the vascular calcification in CKD and propose a plausible yet evolving model of the pathogenic role of αKlotho in this dire complication.

Vascular calcification in CKD

Uremic soft tissue and vascular calcification was described by Virchow over one and a half century ago and he proposed that calcium from bone is metastatically relocated to soft tissue as “Kalk Metastasen” [6]. Nearly half a century ago, Parfitt gave a detailed account on uremic soft tissue calcification [7]. Although the proposed mechanisms of calcification seem anachronistic and superficial by today’s standards, the description of the lesions is very accurate and Parfitt importantly commented that of all the different ectopic sites, arterial calcification was universal in all patients [7]. CKD has reached epidemic proportions in many countries and a 2013 examination of the National Vitals Statistics showed that if one lives to his or her seventies in the United States, the chance of developing Stage 3 or higher CKD is staggeringly high at over 50% [8■]. In a recent analysis of nearly 4,000 subjects from the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) trial, cardiovascular mortality over 7 years was increased by the presence of CKD (hazard ratio 2.24) much more significantly then either diabetes, metabolic syndrome or smoking (hazard ratio ~1.45) after multivariable adjustment [9]. A seminal report from the National Kidney Foundation over one and one half decade ago showed that the mortality from cardiovascular disease in a 20 year old patient on dialysis is the same as an 80 year old person not on dialysis, and the traditional Framingham risk factors cannot account for this grim outcome [10]. Unfortunately, we have not progressed very far since that report. It is true that traditional cardiovascular risk factors are highly prevalent in CKD and clinicians are working hard to control them but in addition, one should be cognizant of an expanding list of uremia-specific cardiovascular risk factors that require attention at various levels of the experimental and clinical fronts- a few examples are asymmetrical dimethylarginine, endothelin, homocysteine, advanced oxidation protein products, advance glycosylation end-products, indoxyl sulfate, fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-23, phosphate, and αKlotho deficiency whose relationship to uremic vasculopathy which will be discussed below.

αKlotho levels in CKD

The features of hyperphosphatemia, high FGF23, short life expectancy, and vascular calcification are shared between the αKlotho-deficient mice and CKD [2, 3, 11, 12], Serum αKlotho levels is decreased in adult CKD stage 2 and linearly declines with eGFR [13]. After multivariable adjustment, serum αKlotho is associated independently with eGFR in full range of CKD [14] [15]. However, the commercial αKlotho assay kits have not been uniform [16■] often yielding inconsistent results of circulating αKlotho in CKD (reviewed [3, 5, 12]). The published data of serum/plasma Klotho in the last 3 years and its relationship to cardiovascular disease and CKD is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Circulating αKlotho levels with renal and cardiovascular disease

| Circulating αKlotho | Vascular disease | Comments | Citation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changes | Sample* | Study subjects | CAD |

Endothelial dysfunction |

Vascular calcification |

Arterial stiffness |

||

| ↓in SCAD ↑↑in NSCAD |

Serum | 371 CAD eGFR≥60 ml/min/1.73m2 |

↓ in severe CAD |

N/A | N/A | N/A | ↓serum αKlotho independently associated with the presence of severe CAD |

[17■■] |

| ↓ protein ↓ mRNA |

Serum Kidney |

14 CKD 1-5 43 HD |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Serum αKlotho lower in HD than compared to pre-HD Renal αKlotho correlated with serum αKlotho |

[18■■] |

| ↓ | Serum | 243 CKD 1-5, no healthy subjects |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Lower serum αKlotho associated with more advanced CKD. |

14 |

| ↓ | Plasma | 76 DM2 Scr < 1.7 mg/dl |

N/A | N/A | N/A | ↓↓ (not by multivariate analysis) |

Arterial stiffness not correlated with serum αKlothoby multivariate analysis RAS blocker increased plasma αKlotho and decreased aortic-pulse wave velocity |

19 |

| No change | Plasma | 321 CKD 2-4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | αKlotho not ↓ with ↓ GFR and not correlated with CV outcome |

20 |

| ↓ | Serum | 87 CKD1-5 21 healthy |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | αKlotho ↓linearly with ↓ eGFR | 15 |

| ↓ | Plasma | 154 children: 69 CKD 1-3, 13 CKD4-5, 28 Dialysis , 44 functioning graft (CKD1-3) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | αKlotho↓in advanced CKD (4-5) and dialysis compared with αKlothoin CKD1-3 and functioning graft with CKD (1-3). |

[21■] |

| ↓ | Serum | 114 CKD 1-5 | N/A | ↓ ↓ (not by multivariate analysis) |

↓ ↓ (not by multivariate analysis) |

↓ ↓ | ↓ αKlotho independently associated with arterial stiffness |

[22■] |

| No change | Serum | 36 PD | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Urine but not serum αKlotho ↓ and correlated with residual GFR |

[23■■] |

| ↓ | Serum | 292 CKD 1-5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | αKlotho ↓ beginning in CKD 2 | 13 |

| Not ↓ in CKD ↓ in ADPKD |

Serum | 32 CKD 1-2 , 99 ADPKD 1-2, 20 healthy |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | αKlotho not ↓ early CKD, but in ADPKD with stage 1-2, and serum αKlotho values correlated inversely with cyst volume and kidney size |

24 |

| ↑ | Serum | 30 CKD 10 healthy |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Serum αKlotho ↑ in CKD | 25 |

ADPKD: adult dominant polycystic kidney disease; CAD: coronary artery disease; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CVD: cardiovascular disease; HD: hemodialysis; N/A: information not available; NSCAD: no significant coronary artery disease (0-49% stenosis in any epicardial coronary artery); PD: peritoneal dialysis; SCAD: significant coronary artery disease (≥50% stenosis in any epicardial coronary artery); DM2; Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Performed with commercial ELISA kit

Because αKlotho levels are affected by many factors including hormones (1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3, FGF23, and PTH), mineral parameters (plasma Ca and Pi), medications (statins [26], renin-angiotensin system (RAS) blockers [19, 27], peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists (PPAR)γ [28]), and age, in addition to kidney function, interpretation of plasma αKlotho levels in CKD/end-stage renal disease (ESRD) requires caution. Data in CKD patients addressing correlations between αKlotho and vasculopathy is currently based on a single assay and appears suboptimal at present. Low serum αKlotho was associated with arterial stiffness, but not with endothelial dysfunction in CKD patients (Table 1) [22]. Low serum αKlotho is independently associated with severity of coronary artery disease in patients with normal kidney function [17]. A definitive conclusion could not be made until one can understand all the variables that affect circulating αKlotho levels and more reliable and accurate assays for αKlotho are available.

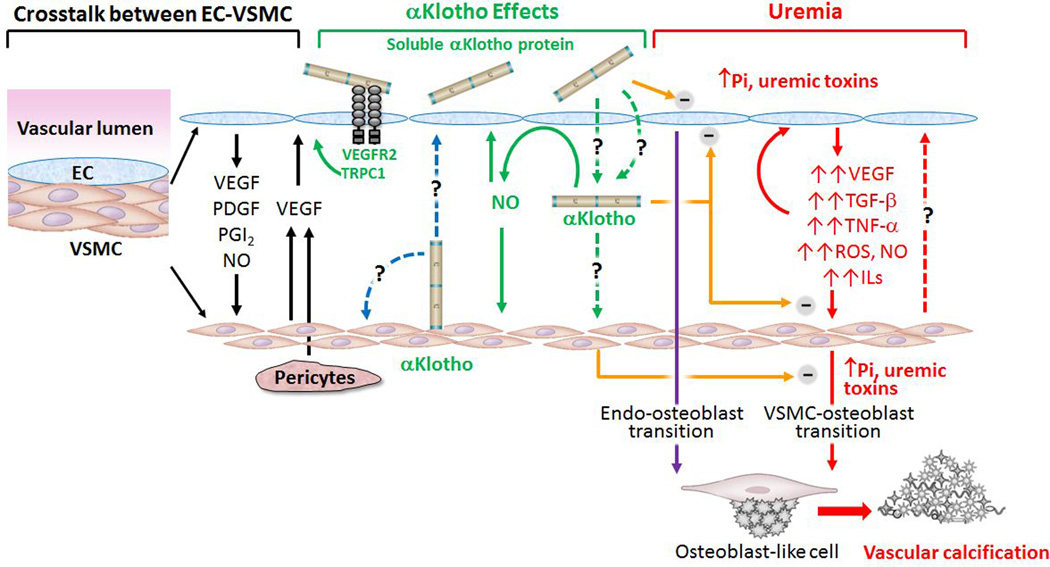

Endothelial: vascular smooth muscle complex- an inseparable functional network

While the study of endothelial (EC) or vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) in isolation permits more definitive conclusions, it is important to note that these cells do not exist in isolation. Blood vessels are composed of endothelial cells, mural cells (smooth muscle cells and pericytes), their shared basement membrane and extracellular matrix. The endothelium lines the entire cardiovascular and lymphatic system [29]. It is not only a barrier but contributes to physiological functions [30–32]. The endothelium can be a primary source of pathophysiology, a secondary player that amplifies pathology, or as a by-standing victim. Intact structure and function of the endothelium is indispensable for maintenance of the integrity of the vasculature. When co-cultured with EC, VSMCs, express more vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β than VSMC cultured in isolation. ECs when co-cultured with VSMCs express higher VEGF than in singly cultured EC, suggesting that VSMC and EC work synergistically [33] (Figure 1 left panel). ECs also released a variety of growth factors and cytokines such as von Willebrand factor (VWF) [34], nitric oxide (NO) [35], and prostacyclin to modulate VSMC function (Figure 1 left panel) [30, 33]. Increasing attention is devoted to the role of endothelium in modulation of vascular smooth muscle cells.

Figure 1. Proposed model of how Klotho affects endothelial cell (EC) -vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) interaction.

Left panel: Normal EC-VSMC cross-talk. Normal EC modulates VSMC growth via release of growth factors (black line in left panel). VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor. PDGF: platelet-derive growth factor, PGI2: Prostaglandin I2, NO: Nitric oxide. VEGF released from pericytes and/or VSMC could also regulate endothelial cell. Right panel: In chronic kidney disease, uremic toxins including high plasma Pi, damage EC and induce release of growth factors, pro-inflammatory cytokines and pro-fibrotic factors, which exacerbate EC injury and also induce VSMC transition to osteoblast and promote vascular calcification in medial layer (red solid lines in right panel). Impaired EC also directly contributes to vascular calcification through endo-osteoblast transition (purple line in right panel). Whether de-differentiated or damaged VSMC could further modulate function of endothelial cells is only speculative (red dash line in right panel). Middle panel: αKlotho is a vascular protective protein. Whether resident aortic αKlotho protein in VSMC functions as autocrine and/or as paracrine mode to modulate VSMC and/or EC remains to be clarified (blue dash line in middle panel). How αKlotho is able to access to VSMC from the circulation and functions as endocrine factor remain to be defined (green dash line in middle panel). αKlotho, regardless of source could increase NO production from EC and NO consequently modulates VSMC and EC function in an autocrine mode (green solid line in middle panel). αKlotho could protect EC from high phosphate and other uremic toxins and also attenuate oxidative stress and pro-inflammatory cytokines induced cell senescence and apoptosis in VSMC (orange line in middle panel). αKlotho also directly inhibits osteoblast transition induced by hyperphosphatemia and uremic milieu (orange line in middle panel). Current experimental and clinical observations suggest that both EC and VSMC endothelium may be potential targets of soluble αKlotho to protect the vasculature from vascular calcification in CKD.

Endothelial cells damaged by uremic milieu [36] or high phosphate [37] show an increase in apoptosis, reactive oxygen species, impaired nitric oxide production, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, pro-fibrotic growth factors, and pro-angiogenic growth factors; all of them do not only induce endothelial dysfunction, but also potentially stimulates VSMC proliferation and dedifferentiation [30, 38] (Figure 1 right panel). Evidence of endothelial effects on vascular calcification was provided when vascular endothelium was shown to contribute to osteoprogenitor cells in vascular calcification. Yao and colleagues used transgenic mice with EC linage reporter and found that the endothelium is a source of osteoprogenitor cells in vascular calcification (Figure 1 right panel) [39■■]. Therefore, endothelium directly contributes to vascular calcification via endothelial-mesenchymal transition. In addition, endotehlium also stimulates VSMC to initiate or participate in vascular calcification. It is well known that high Pi [11, 40–42] and other uremic insults such as indoxyl sulfate [43], FGF-23 [44■] could induce calcification in VSMC; but whether and how impaired VSMC alters EC is yet to be defined (Figure 1 right panel).

αKlotho action on endothelium

Compared to the amount of investigative work devoted to the VSMC (see below), the study of αKlotho action on the endothelium is rather modest. One should briefly note that one enigma in αKlotho biology is how this 130 kD protein leaves the endovascular space to reach its target organs which are impressively widespread in locale. In the renal peritubular capillary, αKlotho appears to have an unparalleled ability to exit the peritubular but not the glomerular capillary, through yet undefined mechanisms [45, 46]. Unless αKlotho can perform this feat in every capillary bed as it does in the peritubular capillary (Figure 1 middle panel), it will be a formidable challenge indeed for it to act on its myriads of target organs. One possible model that can potential bypass the access problem, or at least provide a parallel pathway, is that αKlotho may act on the endothelium and produce a secondary effect thereafter via endothelial-vascular smooth muscle cross-talk (Figure 1 middle panel). Or αKlotho produced in VSMC and regulates VSMC function as autocrine mode or/and regulates EC as paracrine mode (Figure 1 middle panel). This is only a conjecture that needs exploration.

The study of the action of αKlotho on the endothelium was initiated soon after its discovery. The homozygous αKlotho hypomorphic mice have decreased vasodilation in response to acetylcholine [47]. The Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty rat had diminished renal αKlotho expression and impaired aortic relaxation in response to acetylcholine, and both could be attenuated with thiazolidinedione [48]. A similar rescue can also be achieved by viral delivery of αKlotho [49]. This finding inferred but did not prove that circulating αKlotho takes responsible for the normal vasorelaxation due to regulation of NO production in vascular endothelium (Figure 1 middle panel).

In cultured EC (Figure 1), treatment with αKlotho alleviated the induction of adhesion molecules [50]; prevented the increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS) activity, mitochondrial potential and cell apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α [51]. αKlotho is also able to ameliorate the indxyl sulfate-induced endothelial dysfunction and reduce ROS and NO release and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression in EC (Figure 1 middle panel) [52]. The most definitive study to date of direct effects of αKlotho on the endothelium was conducted by Kusaba and coworkers [53]. αKlotho-deficient mice have increased VEGF-mediated calcium influx, down-regulation of vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherin, increased apoptosis and excessive permeability of vessels. The KL2 domain of αKlotho protein binds directly to VEGF receptor 2 and endothelial transient-receptor potential Ca2+ channel 1 on the extracellular side and promote their co-internalization thereby reducing the Ca2+-activated and caspase-mediated destruction of catenin and VE-cadherin on the cell surface (Figure 1 middle panel).

αKlotho action on vascular smooth muscle

αKlotho mRNA was found in murine aorta with the highly sensitive RT-PCR assay [1]. Subsequently, its present in aorta was confirmed independently by RT-PCR in human [41, 54] and rat [55, 56■■]. In contrast, αKlotho protein in the aorta was only detected by a few laboratories [41, 44, 55] (Table 2). Very clear negative results were also obtained [38, 50].

Table 2.

αKlotho expression in human and animal aortas and αKlotho effect on vascular calcification in vivo and in vitro

| αKlotho expression | αKlotho effect | Comments | Citation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aorta | Cultured VSMC |

Intact animal |

Cultured aorta |

Cultured VSMC |

||

| ↓mRNA and protein in human CKD |

↓mRNA and protein in human VSMC by calcifying media , TNF-α |

αKlotho knockdown →↑ calcification in human VSMC |

VDRA →↑αKlotho turns FGF23 from promotion to suppression of calcification by calcifying media in human cultured VSMC FGF23. αKlotho in aortic ring ↑ by VDRA treatment. Human aorta αKlotho deficiency in CKD can be reversed ex vivo with VDRA and calcification is attenuated |

41 | ||

| No mRNA or protein in mouse aorta |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | VDRA in vivo → ↑plasma αKlotho→↓VC in CKD mice VDRA may be beneficial by increasing circulating αKlotho |

57 |

| mRNA but no protein in mouse aorta |

mRNA but no protein in bovine VSMC |

No VC in SM22-Cre- αklothofl/fl mice |

No αKlotho protein in aorta and gene deletion in aorta has no effect FGF23 has not effect on VC in vitro and vascular function ex vivo Aortic αKlotho has no role in VC |

[56■■] | ||

| No mRNA in normal and calcified aortas of CKD mice |

No mRNA in human and mice |

No effect on human and mice VSMC |

No αKlotho expression in human and murine aorta and in cultured VSMC No aortic αKlotho expression and no αKlotho effect in vitro |

58 | ||

| ↑ mRNA and protein in calcified aorta of Enpp1−/− mice |

↑ mRNA and protein in mice by calcified media |

N/A | N/A | N/A | Calcification increases αKlotho and FGF23 expression in aorta ↑αKlotho associated with ↑ VC. Causality not established. |

59 |

| mRNA in human aorta, coronary arteries, and thrombus |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

αKlotho mRNA detectable in human arteries and thrombi of occlusive coronary disease. Significance unknown. |

54 |

| ↓mRNA and protein in ldlr−/− CKD mice |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Low aortic αKlotho but high circulating αKlotho associated with vascular calcification in ldlr−/− CKD mice αKlotho in the vasculature may be more important |

55 |

| N/A | N/A | αKlotho protein injection → ↓ VC in Kl/Kl mice |

N/A | N/A | Soluble (extracellular domain) αKlotho improves VC in Kl/Kl mice CirculatingαKlotho may be more important |

60 |

| N/A | N/A | Tg-Kl → ↓ VC in mice |

N/A | αKlotho protein →↓ VC induced by high Pi in rat VSMC |

Soluble αKlotho protein directly protects VSMC from high phosphate induced calcification |

11 |

| Expression in aorta but not in VSMC |

None | N/A | N/A | αKlotho permits FGF23 to induce VC |

αKlotho is present in rat aorta, but not in VSMC. Transfected αKlotho is required for FGF23 to enhance Pi induced VC in rat VSMC. No native αKlotho in VSMC but with overexpression, αKlotho worsens VC |

[44■] |

Enpp1: Ectonucleotidepyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1; Kl/Kl: homozygous Klothohypomorph; ldlr: LDL receptor; N/A: information not available; Tg-Kl: transgenic Klotho with overexpressing Klotho; VC: vascular calcification; VSMC: vascular smooth muscle cells; VDRA: Vitamin D receptor agonist.

The association of αKlotho deficiency with vascular calcification was documented in αKlotho hypomorphic mice [1] and transgenic overexpression or viral delivery of αKlotho rescued the phenotype [61–63]. Medial vascular calcification is one of the most prominent features in both CKD and αKlotho-deficient animals. Mice overexpressing αKlotho having high circulating αKlotho had much less vascular calcification after CKD induction, while mice with low circulation αKlotho had more severe vascular calcification [11]. These whole animal data support but do not prove a causal relation of αKlotho deficiency with vascular calcification. Thus one still does not know if αKlotho plays a direct role in vasculature.

Theoretically, elucidation of αKlotho expression and location in the aorta is of fundamental importance to αKlotho biology in the vasculature. Pragmatically, it is also an important question for therapeutics. If resident αKlotho in the aorta protects the vasculature against vascular calcification as a transmembrane protein or in a paracrine or autocrine manner, up-regulation of native vascular αKlotho expression would be the therapeutic objective for prevention or treatment of vascular calcification [41]. In contrast, if circulating αKlotho protects against vascular calcification in an endocrine manner, then soluble αKlotho would be potential therapeutic agent. Lau and colleagues showed that vitamin D receptor activators in vivo increased serum αKlotho concentration, but not in aorta, but still reduced vascular calcification [57]. Specific Klotho deletion in vascular smooth muscle further challenged the concept that αKlotho in VSMC plays an important role [56], since there was no enhanced vascular calcification in mice with specific αKlotho deletion in VSMC [56]. Furthermore, increased αKlotho mRNA was found in calcified aorta in Enpp1−/− mice [59] that have extensive ectopic calcification, and seemingly αKlotho protein is also increased in atherosclerotic arteries [54]. These findings (assuming not confounded by reagent problems) are against resident αKlotho being protective. Intraperitoneal administration of a large amount of recombinant αKlotho, identical to extracellular domain of membrane αKlotho, [60] αKlotho gene delivery [62], and increased of endogenous circulating αKlotho [57] all reduced vascular calcification and improved endothelial functions [49], supporting that soluble αKlotho plays a pivotal role in protection of vasculature against calcification in the manner of endocrinal factor (Table1). It is important to note that this does not rule out a simultaneous effect of resident αKlotho protein in the vasculature.

To avoid the complexity of systemic administration and secondary effects, soluble αKlotho protein was added to or transfected into VSMCs. Either maneuver effectively attenuated high phosphate-induced osteogenic transition and abolished calcification of VSMC suggesting that αKlotho might be a direct vascular protective protein (Figure 1 middle panel) [11, 41]. However, one study did not see any effect of αKlotho protein on FGF23 and high phosphate-mediated calcification in either human and mouse VSMCs [58]. The differential effects of αKlotho on high phosphate-induced calcification in vitro may be due to differences in VSMCs or to different αKlotho protein preparations used. Surprisingly, deleterious effect of αKlotho on vascular calcification was found in one study in cultured rat VSMC where FGF23 accelerated high Pi-induced calcification only when αKlotho was overexpressed (Table 1) [44]. Thus the in vitro system intended to generate definitive data on the direct effects of αKlotho has resulted in a conflicting database. The reasons for the disparity are unclear but different VSMCs preparations and induction of calcification, and different ways of administering αKlotho are possibilities.

Conclusion

Endothelial dysfunction/stiffness is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality in CKD patients [64]. The endothelium is constantly bathed in blood and is clearly a potential target of uremic toxicity. CKD patients had lower flow-mediated dilation (FMD) which correlated with higher C-reactive protein and increased left ventricular mass index (LVMI) [65] and there is some improvement in FMD after kidney transplant [66]. The relationship between LVMI and FMD remained significant after adjusting for age, diabetes, and smoking. Recently, the endothelium was shown to be a source of osteo-progenitor cells in in diabetic mice [39] (Figure 1 right panel). The potential role of damaged endothelium in mediation of osteogenic transition and vascular calcification is proposed in Figure 1 right panel and remains to be tested. The disturbed interplay of endothelium and vascular smooth muscle cells in vascular calcification in CKD has not been clearly addressed. The protection of endothelium may be a novel therapeutic target for treatment of vascular calcification in CKD as for atherosclerosis [67]. Soluble αKlotho may have potential action on modulation of endothelium and smooth muscle cells individually through regulation of VEGF signaling, NO production and neutralization of pro-inflammatory cytokine and pro-fibrogenic factors (Figure 1 middle panel). Conceivably, healthy endothelium potentially protects smooth muscle cells from vascular calcification promoted by uremic milieu including high phosphate and high FGF23.

Studies of endothelial or vascular smooth muscle cells in isolation may not fully represent the system and intact animal studies are important but limited in dissecting out the role of individual players. Co-culture of vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells may be a viable intermittent system that will help understand the interactions and how αKlotho action maintains normal structure and function of vasculature. Despite controversies of αKlotho expression and its actin on cultured cells, the current wisdom still favors, although not prove, a pathogenic role of αKlotho deficiency in vascular calcification. We propose that the endothelium-vascular smooth muscle complex may be a potential target of αKlotho in vascular calcification in CKD.

Key points.

Despite mixed results of plasma αKlotho levels and aortic αKlotho expression in CKD, majority of clinical and experimental results supported that αKlotho deficiency is associated with vascular calcification.

Soluble αKlotho protein has been shown to protect endothelial cell from high phosphate and oxidative stress, and block osteogenic transition of smooth muscle cell induced by high phosphate.

Normal interplay between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells is indispensable for maintenance of normal vascular structure and function even though detailed molecular mechanisms remain to be illustrated.

Administration of soluble αKlotho and/or modulators of αKlotho expression may hold promise as therapeutic approaches for management of vascular calcification in CKD/ESRD patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01-DK091392, R01-DK092461), The George M. O’Brien Kidney Research Center at UT Southwestern Medical Center (P30-DK-07938), the Simmons Family Foundation, and the Charles and Jane Pak Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

Papers of particular interest, published with the annual period of review, have been highlighted as

■ of special interest

■■ of outstanding interest

- 1.Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390:45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu MC, Kuro-o M, Moe OW. Renal and extrarenal actions of Klotho. Seminars in nephrology. 2013;33:118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hu MC, Shiizaki K, Kuro-o M, Moe OW. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and Klotho: physiology and pathophysiology of an endocrine network of mineral metabolism. Annual review of physiology. 2013;75:503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183727. ■ A comprehensive review summarizing physiology and pathophysiology of FGF23 and Klotho.

- 4.Hu MC, Kuro-o M, Moe OW. The emerging role of Klotho in clinical nephrology. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2012;27:2650–2657. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu MC, Kuro-o M, Moe OW. Klotho and chronic kidney disease. Contributions to nephrology. 2013;180:47–63. doi: 10.1159/000346778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Virchow R. Kalk metastasen. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat. 1855;8:103–103. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parfitt AM. Soft-tissue calcification in uremia. Archives of internal medicine. 1969;124:544–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grams ME, Chow EK, Segev DL, Coresh J. Lifetime incidence of CKD stages 3-5 in the United States. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2013;62:245–252. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.009. ■■ Lifetime risks of developing chronic kidney disease (stages 3a or higher-eGFR]<60 mL/min/1.73 m2) is up to 60% in the United States.

- 9.Baber U, Gutierrez OM, Levitan EB, et al. Risk for recurrent coronary heart disease and all-cause mortality among individuals with chronic kidney disease compared with diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and cigarette smokers. American heart journal. 2013;166:373–380. e372. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Sarnak MJ. Clinical epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in chronic renal disease. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1998;32:S112–S119. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9820470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, et al. Klotho deficiency causes vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2011;22:124–136. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009121311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu MC, Kuro-o M, Moe OW. Secreted klotho and chronic kidney disease. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2012;728:126–157. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0887-1_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shimamura Y, Hamada K, Inoue K, et al. Serum levels of soluble secreted alpha-Klotho are decreased in the early stages of chronic kidney disease, making it a probable novel biomarker for early diagnosis. Clinical and experimental nephrology. 2012;16:722–729. doi: 10.1007/s10157-012-0621-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HR, Nam BY, Kim DW, et al. Circulating alpha-klotho levels in CKD and relationship to progression. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2013;61:899–909. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pavik I, Jaeger P, Ebner L, et al. Secreted Klotho and FGF23 in chronic kidney disease Stage 1 to 5: a sequence suggested from a cross-sectional study. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2013;28:352–359. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Heijboer AC, Blankenstein MA, Hoenderop J, et al. Laboratory aspects of circulating alpha-Klotho. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2013;28:2283–2287. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft236. ■ A study alerting that commercial ELISA kits for the measurement of αKlotho differ in quality and one needs reliable assays to better evaluate circulating Klotho lelvels.

- 17. Navarro-Gonzalez JF, Donate-Correa J, Muros de Fuentes M, et al. Reduced Klotho is associated with the presence and severity of coronary artery disease. Heart. 2014;100:34–40. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304746. ■■ A large scale clinical study demonstrating that serum Klotho is reduced and independently associated with the presence of severe coronary artery disease.

- 18. Sakan H, Nakatani K, Asai O, et al. Reduced Renal alpha-Klotho Expression in CKD Patients and Its Effect on Renal Phosphate Handling and Vitamin D Metabolism. PloS one. 2014;9:e86301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086301. ■■ CKD patients with biopsy showing that renal αKlotho levels are reduced along with a decrease in serum Klotho.

- 19.Karalliedde J, Maltese G, Hill B, et al. Effect of renin-angiotensin system blockade on soluble Klotho in patients with type 2 diabetes, systolic hypertension, and albuminuria. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2013;8:1899–1905. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02700313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seiler S, Wen M, Roth HJ, et al. Plasma Klotho is not related to kidney function and does not predict adverse outcome in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney international. 2013;83:121–128. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wan M, Smith C, Shah V, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 and soluble klotho in children with chronic kidney disease. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2013;28:153–161. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs411. ■ Only clinical study examining children with CKD, dialysis, and renal transplantation showing CKD 4-5 dialysis children had lower serum Klotho compared with CKD 1-3 and functioning renal graft CKD 1-3.

- 22. Kitagawa M, Sugiyama H, Morinaga H, et al. A decreased level of serum soluble Klotho is an independent biomarker associated with arterial stiffness in patients with chronic kidney disease. PloS one. 2013;8:e56695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056695. ■ Patients with CKD have low serum Klotho and reduced Klotho is independently associated with arterial stiffness.

- 23.Akimoto T, Shiizaki K, Sugase T, et al. The relationship between the soluble Klotho protein and the residual renal function among peritoneal dialysis patients. Clinical and experimental nephrology. 2012;16:442–447. doi: 10.1007/s10157-011-0582-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavik I, Jaeger P, Ebner L, et al. Soluble klotho and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2012;7:248–257. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09020911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugiura H, Tsuchiya K, Nitta K. Circulating levels of soluble alpha-Klotho in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clinical and experimental nephrology. 2011;15:795–796. doi: 10.1007/s10157-011-0511-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoon HE, Lim SW, Piao SG, et al. Statin Upregulates the Expression of Klotho , an Anti-Aging Gene, in Experimental Cyclosporine Nephropathy. Nephron. Experimental nephrology. 2012;120:e123–e133. doi: 10.1159/000342117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitani H, Ishizaka N, Aizawa T, et al. In vivo klotho gene transfer ameliorates angiotensin II-induced renal damage. Hypertension. 2002;39:838–843. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000013734.33441.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Li Y, Fan Y, et al. Klotho is a target gene of PPAR-gamma. Kidney international. 2008;74:732–739. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lutter S, Xie S, Tatin F, Makinen T. Smooth muscle-endothelial cell communication activates Reelin signaling and regulates lymphatic vessel formation. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;197:837–849. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201110132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Triggle CR, Samuel SM, Ravishankar S, et al. The endothelium: influencing vascular smooth muscle in many ways. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology. 2012;90:713–738. doi: 10.1139/y2012-073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moody WE, Edwards NC, Madhani M, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease in early-stage chronic kidney disease: cause or association? Atherosclerosis. 2012;223:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aird WC. Endothelial cell heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2012;2:a006429. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heydarkhan-Hagvall S, Helenius G, Johansson BR, et al. Co-culture of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells affects gene expression of angiogenic factors. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2003;89:1250–1259. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meng H, Zhang X, Lee SJ, Wang MM. Von Willebrand Factor Inhibits Mature Smooth Muscle Gene Expression through Impairment of Notch Signaling. PloS one. 2013;8:e75808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kusche-Vihrog K, Jeggle P, Oberleithner H. The role of ENaC in vascular endothelium. Pflugers Archiv : European journal of physiology. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1356-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carracedo J, Buendia P, Merino A, et al. Cellular senescence determines endothelial cell damage induced by uremia. Experimental gerontology. 2013;48:766–773. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Marco GS, Hausberg M, Hillebrand U, et al. Increased inorganic phosphate induces human endothelial cell apoptosis in vitro. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2008;294:F1381–F1387. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00003.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li D, Zhang C, Song F, et al. VEGF regulates FGF-2 and TGF-beta1 expression in injury endothelial cells and mediates smooth muscle cells proliferation and migration. Microvascular research. 2009;77:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yao Y, Jumabay M, Ly A, et al. A role for the endothelium in vascular calcification. Circulation research. 2013;113:495–504. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301792. ■■ Murine experiments with lineage tracing showing that endothelium is a source of osteoprogenitor cells in vascular calcification in mice with diabetes and matrix Gla protein knock-out.

- 40.Lau WL, Pai A, Moe SM, Giachelli CM. Direct effects of phosphate on vascular cell function. Advances in chronic kidney disease. 2011;18:105–112. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lim K, Lu TS, Molostvov G, et al. Vascular Klotho deficiency potentiates the development of human artery calcification and mediates resistance to fibroblast growth factor 23. Circulation. 2012;125:2243–2255. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.053405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shroff R. Phosphate is a vascular toxin. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:583–593. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muteliefu G, Shimizu H, Enomoto A, et al. Indoxyl sulfate promotes vascular smooth muscle cell senescence with upregulation of p53, p21, and prelamin A through oxidative stress. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology. 2012;303:C126–C134. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00329.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jimbo R, Kawakami-Mori F, Mu S, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 accelerates phosphate-induced vascular calcification in the absence of Klotho deficiency. Kidney international. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.332. ■ A study showing Klotho protein is expressed in total lysate from whole aorta, but not in vascular smooth muscle cells.

- 45.Hu MC, Shi M, Zhang J, et al. Klotho: a novel phosphaturic substance acting as an autocrine enzyme in the renal proximal tubule. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2010;24:3438–3450. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-154765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu MC, Shi M, Addo T, et al. Renal Production, Uptake, and Metabolism of Circulating Klotho [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagai R, Saito Y, Ohyama Y, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in the klotho mouse and downregulation of klotho gene expression in various animal models of vascular and metabolic diseases. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2000;57:738–746. doi: 10.1007/s000180050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamagishi T, Saito Y, Nakamura T, et al. Troglitazone improves endothelial function and augments renal klotho mRNA expression in Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) rats with multiple atherogenic risk factors. Hypertension research : official journal of the Japanese Society of Hypertension. 2001;24:705–709. doi: 10.1291/hypres.24.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saito Y, Nakamura T, Ohyama Y, et al. In vivo klotho gene delivery protects against endothelial dysfunction in multiple risk factor syndrome. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2000;276:767–772. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maekawa Y, Ishikawa K, Yasuda O, et al. Klotho suppresses TNF-alpha-induced expression of adhesion molecules in the endothelium and attenuates NF-kappaB activation. Endocrine. 2009;35:341–346. doi: 10.1007/s12020-009-9181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carracedo J, Buendia P, Merino A, et al. Klotho modulates the stress response in human senescent endothelial cells. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2012;133:647–654. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang K, Nie L, Huang Y, et al. Amelioration of uremic toxin indoxyl sulfate-induced endothelial cell dysfunction by Klotho protein. Toxicology letters. 2012;215:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kusaba T, Okigaki M, Matui A, et al. Klotho is associated with VEGF receptor-2 and the transient receptor potential canonical-1 Ca2+ channel to maintain endothelial integrity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:19308–19313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008544107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Donate-Correa J, Mora-Fernandez C, Martinez-Sanz R, et al. Expression of FGF23/KLOTHO system in human vascular tissue. International journal of cardiology. 2013;165:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.08.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fang Y, Ginsberg C, Sugatani T, et al. Early chronic kidney disease-mineral bone disorder stimulates vascular calcification. Kidney international. 2014;85:142–150. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lindberg K, Olauson H, Amin R, et al. Arterial klotho expression and FGF23 effects on vascular calcification and function. PloS one. 2013;8:e60658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060658. ■■ mRNA but not protein of Klotho was found in aorta and specific deletion of Klotho mouse in vascular smooth muscle cells did not induce vascular calcification.

- 57.Lau WL, Leaf EM, Hu MC, et al. Vitamin D receptor agonists increase klotho and osteopontin while decreasing aortic calcification in mice with chronic kidney disease fed a high phosphate diet. Kidney international. 2012;82:1261–1270. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scialla JJ, Lau WL, Reilly MP, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 is not associated with and does not induce arterial calcification. Kidney international. 2013;83:1159–1168. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu D, Mackenzie NC, Millan JL, et al. A protective role for FGF-23 in local defence against disrupted arterial wall integrity? Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2013;372:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen TH, Kuro OM, Chen CH, et al. The secreted Klotho protein restores phosphate retention and suppresses accelerated aging in Klotho mutant mice. European journal of pharmacology. 2013;698:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, et al. Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho. Science. 2005;309:1829–1833. doi: 10.1126/science.1112766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Masuda H, Chikuda H, Suga T, et al. Regulation of multiple ageing-like phenotypes by inducible klotho gene expression in klotho mutant mice. Mechanisms of ageing and development. 2005;126:1274–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shiraki-Iida T, Iida A, Nabeshima Y, et al. Improvement of multiple pathophysiological phenotypes of klotho (kl/kl) mice by adenovirus-mediated expression of the klotho gene. The journal of gene medicine. 2000;2:233–242. doi: 10.1002/1521-2254(200007/08)2:4<233::AID-JGM110>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Luksha L, Stenvinkel P, Hammarqvist F, et al. Mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction in resistance arteries from patients with end-stage renal disease. PloS one. 2012;7:e36056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Poulikakos D, Ross L, Recio-Mayoral A, et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy and endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. European heart journal cardiovascular Imaging. 2014;15:56–61. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jet120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yilmaz MI, Sonmez A, Saglam M, et al. Longitudinal analysis of vascular function and biomarkers of metabolic bone disorders before and after renal transplantation. American journal of nephrology. 2013;37:126–134. doi: 10.1159/000346711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Barton M. Prevention and endothelial therapy of coronary artery disease. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2013;13:226–241. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]