Lymphangioleiomyomatosis is a multisystem disease affecting women, which is characterized by cystic lung destruction, lymphatic abnormalities (e.g., lymphangioleiomyomas), and abdominal tumors which are found primarily in the kidneys, and consist of smooth muscle cells, vascular structures and adipocytes, termed angiomyolipomas.1,2 Lymphangioleiomyomatosis occurs sporadically and in about one-third of women with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), an autosomal dominant disorder with variable penetrance.1,2 In either case, LAM is caused by mutations of TSC1 or TSC2, two genes that encode, respectively, hamartin and tuberin, two proteins that regulate cell growth.3,4 Deficiency of these proteins causes activation of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) downstream elements, leading to increased cell proliferation and size (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

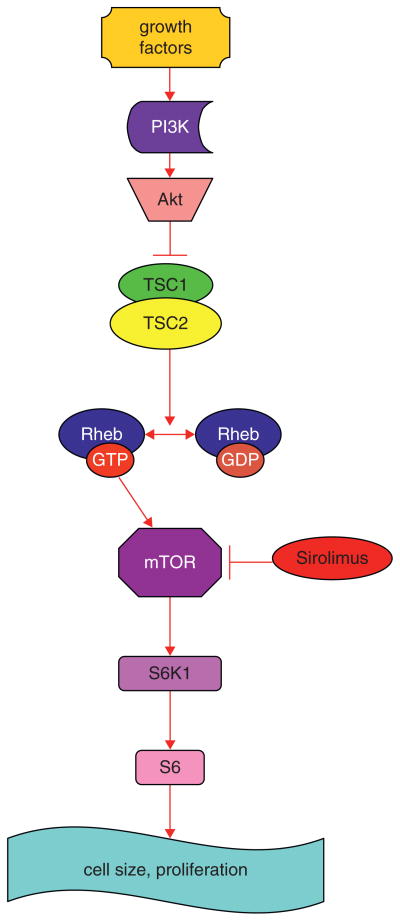

Simplified schematic model of TSC1 and TSC2 pathways. The TSC1/TSC2 complex has roles in cell cycle progression and in cell size and proliferation. This complex stimulates the conversion of active Rheb-GTP to inactive Rheb-GDP, resulting in inactive Rheb. Rheb controls mTOR, a kinase that controls translation through phosphorylation of S6K1. Sirolimus inhibits mTOR. Abbreviations: PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; Akt: protein kinase B; mTOR: mammalian target of rapamycin; Rheb GAP: GTPase-activating protein for Ras homolog enriched in brain; S6K1: S6 kinase 1 (modified from Ref. 10).

Sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis is a rare disease occurring in circa 2–5/1,000,000 persons.1,2 Yet, for those afflicted, LAM is devastating. Progressive lung destruction leads to respiratory failure, lung transplantation or death.1,2 Lymphatic involvement may cause chylous pleural effusions, ascites and lymphangioleiomyomas, abdominal tumors that may mimic lymphomas and sarcomas.5 Renal angiomyolipomas may be associated with abdominal hemorrhage, requiring partial or total nephrectomy or embolization of arterial feeding vessels.6

In the past, patients with LAM were advised to undergo bilateral oophorectomy and hysterectomy and/or be treated with anti-estrogen agents such as progesterone or gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues. No controlled studies showing that these therapies are beneficial to the patients have ever been carried out.7,8

Several studies have demonstrated the important role of the TSC1/TSC2 complex in cell cycle progression and in cell size and proliferation.9,10 Tuberin binds a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, thus stabilizing it, resulting in inhibition of cell cycle progression. Tuberin also has a GTPase activating protein activity, which converts Ras homolog enriched in brain (Rheb)-GTP to Rheb-GDP, resulting in inactivation of Rheb (Fig. 1) and reduction in activity of mTOR, a kinase that controls translation through the phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 and S6K1 (Fig. 1). Protein kinase B (Akt), when activated by growth factors, phosphorylates and inhibits tuberin, resulting in increased cell size and proliferation.9,10

Sirolimus (Rapamycin), in the presence of FKBP12 (FK506-binding protein), inhibits mTOR. Animal models with a functionally null germline mutation of Tsc2 spontaneously develop renal cell carcinomas which decrease in size following administration of sirolimus.11,12 In patients with angiomyolipomas, tumor size decreased by half after 1 year of sirolimus therapy, while lung function improved in some patients but not in others.13 Other studies have shown that sirolimus therapy leads to resolution of chylous effusions in post-transplant LAM patients,14 decreased the size of giant cell astrocytomas and reduced the frequency of seizures in TSC patients.15 Results of a multicenter placebo-controlled randomized trial just completed (MILES trial), showed that sirolimus stabilized lung function, and improved symptoms and quality of life in patients with LAM.16 There was a highly significant difference in the change in lung function over 1 year of therapy between sirolimus-treated and placebo-treated patients.16 In another study, sirolimus therapy improved chylous effusions and/or lymphangioleiomyomas.17 By 3–6 months of therapy, effusions start to resolve and complete resolution may be observed, pre-empting the need for repeated thoracentesis, chest tube drainage or pleurodesis.17

These observations provide the rationale for the use of sirolimus in the treatment of selected LAM patients. Sirolimus therapy may be considered for patients that fulfill the inclusion/exclusion criteria for MILES, those with rapidly progressing lung disease, those with chylous effusions that compromise the lung function and require frequent drainage or pleurodesis, and patients with large symptomatic thoraco-abdominal lymphangioleiomyomas. The starting dose of sirolimus is 2 mg/day. Sirolimus levels must be monitored and dosage adjusted to attain serum trough levels between 5 and 15 ng/ml, a range thought to be therapeutic for patients with renal transplants. The occurrence of adverse events associated with sirolimus therapy, such as, oral mucosa ulcers, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, proteinuria, increased serum creatinine, infections, and sirolimus-related interstitial pneumonitis, mandate close patient monitoring, and may require withholding of the drug or reduction in dose. In addition, given the limited experience with sirolimus in the treatment of LAM, it is not known whether treatment may have to be continued for life, when it should be started, the optimal drug levels, or if sirolimus resistance will eventually develop.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Research funded by the Intramural Research Program, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Taveira-DaSilva AM, Gustavo Pacheco-Rodriguez G, Joel Moss J. The natural history of lymphangioleiomyomatosis: markers of severity, rate of progression and prognosis. Lymphatic Res Biol. 2010;8:9–19. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2009.0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson SR, Cordier JF, Lazor R, Cottin V, Costabel U, Harari S, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:14–26. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00076209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smolarek TA, Wessner LL, McCormack FX, Mylet JC, Menon AG, Henske EP. Evidence that lymphangiomyomatosis is caused by TSC2 mutations: chromosome 16p13 loss of heterozygosity in angiomyolipomas and lymph nodes from women with lymphangiomyomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:810–5. doi: 10.1086/301804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carsillo T, Astrinidis A, Henske EP. Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex gene TSC2 are a cause of sporadic pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6085–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.11.6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glasgow CG, Taveira-DaSilva A, Pacheco-Rodriguez G, Steagall WK, Tsukada K, Cai X, et al. Involvement of lymphatics in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Lymphat Res Biol. 2009;7:221–8. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2009.0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC. Renal angiomyolipomata. Kidney Int. 2004;66:924–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taveira-Dasilva AM, Stylianou MP, Hedin CJ, Hathaway O, Moss J. Decline in lung function in patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis treated with or without progesterone. Chest. 2004;126:1867–74. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.6.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harari S, Cassandro R, Chiodini J, Taveira-DaSilva AM, Moss J. Effect of a gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogue on lung function in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Chest. 2007;133:448–54. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goncharova EA, Krymskaya VP. Pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM): progress and current challenges. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:369–82. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taveira-Dasilva AM, Steagall WK, Moss J. Therapeutic options for lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM): where we are, where we are going. Med Rep. 2009:1. doi: 10.3410/M1-93. pii: 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El-Hashemite N, Zhang H, Walker V, Hoffmeister KM, Kwiatkowski DJ. Perturbed IFN-gamma-Jak-signal transducers and activators of transcription signaling in tuberous sclerosis mouse models: synergistic effects of rapamycin-IFN-gamma treatment. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3436–43. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenerson H, Dundon TA, Yeung RS. Effects of rapamycin in the Eker rat model of tuberous sclerosis complex. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:67–75. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000147727.78571.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bissler JJ, McCormack FX, Young LR, Elwing JM, Chuck G, Leonard JM, et al. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:140–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohara T, Oto T, Miyoshi K, Tao H, Yamane M, Toyooka S, et al. Sirolimus ameliorated post-lung transplant chylothorax in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:e7–8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krueger DA, Care MM, Holland K, Agricola K, Tudor C, Mangeshkar P, et al. Everolimus for subependymal giant-cell astrocytomas in tuberous sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1801–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCormack FX, Yoshikazu Y, Moss J, Singer LG, Strange C, Nakata K, et al. MILES Trial Group. Multicenter international lymphangioleiomyomatosis efficacy and safety of sirolimus (MILES) trial. New Engl J Med. 2011;364:1595–606. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taveira-DaSilva AM, Hathaway O, Stylianou M, Moss J. Changes in lung function and chylous effusions in patients with lymphangioleiomyomatosis treated with sirolimus. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:797–805. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-154-12-201106210-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]