Abstract

The study assessed the relationship between postpartum intimate partner violence (IPV) and postpartum health risks among young mothers over time. Data were collected from 2001 to 2005 on young women aged 14–25 attending obstetrics and gynecology clinics in two US cities. Postpartum IPV (i.e., emotional, physical, sexual) was assessed at 6 and 12 months after childbirth (n = 734). Four types of postpartum IPV patterns were examined: emerged IPV, dissipated IPV, repeated IPV, and no IPV. Emerged IPV occurred at 12 months postpartum, not 6 months postpartum. Dissipated IPV occurred at 6 months postpartum, not 12 months postpartum. Repeated IPV was reported at 6 months and 12 months postpartum. Postpartum health risks studied at both time points were perceived stress, depression, fear of condom negotiation, condom use, infant sleeping problems, and parental stress. Repeated measures analysis of covariance was used. The proportion of young mothers reporting IPV after childbirth increased from 17.9 % at 6 months postpartum to 25.3 % at 12 months postpartum (P < 0.001). Emerged and/or repeated postpartum IPV were associated with increased perceived stress, depression, fear of condom negotiation, and infant sleeping problems as well as decreased condom use (P < 0.05). Dissipated postpartum IPV was associated with decreased depression (P < 0.05). IPV screening and prevention programs for young mothers may reduce health risks observed in this group during the postpartum period.

Keywords: Adolescent and young adult mothers, Postpartum intimate partner violence, Prospective study

Introduction

Studies show that young mothers experience a range of adverse health risks during the postpartum period. Kingston et al. [1] found that adolescent and young adult mothers were more likely to experience stressful life events, postpartum depression, unintended pregnancy, and rate their infants’ health suboptimal as compared to adult mothers.

Few studies have examined the role of intimate partner violence (IPV) on young mothers’ postpartum health risks despite research showing young women experience some of the highest rates of IPV. A World Health Organization study in twelve countries observed younger age was associated with increased risk of IPV during the past year [2]. In the US from 1993 to 2003, young adult women (20–24 years) were at greatest risk of intimate partner violence and adolescent women (16–19 years) ranked third nationally [3]. According to a national survey in 16 US states, IPV risk during pregnancy doubled for women under 20 years of age [4]. After childbirth, Harrykissoon et al. [5] found that physical IPV among adolescents was as high as 21.3 % at 3 months postpartum and 78 % of these women reported not experiencing IPV before pregnancy.

The current study documented IPV prevalence after childbirth and examined the impact of postpartum IPV on health risks prevalent among young mothers. Based on previous research on young women and/or IPV, psychological (i.e., perceived stress, depression), sexual (e.g., condom negotiation, condom use), and infant-related outcomes (i.e., infant sleeping problems, parental stress) were considered. A study found that postpartum adolescents and young adults were more likely to report 3 or more stressful life events in the year preceding childbirth compared to adults [1]. A study on US mothers found women who had been abused reported higher levels of parental stress than non-abused women [6]. Beydoun et al.’s [7] meta-analysis of research from 1980 to 2010 found a 1.5 to 2-fold increased risk of depressive symptoms and postpartum depression among women exposed to IPV versus non-exposed women. In a cross-sectional study by Decker et al. [8], young women (16–29 years) in recent abusive relationships were more likely to report forced condom nonuse and fear of requesting condoms. IPV has also been associated with difficult infant temperament at 12 months postpartum among mothers aged 18 years and older [9].

Methods

Participants

Data from this study come from baseline and follow-up interviews collected from pregnant women aged 14–25 enrolled in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted in two US cities: New Haven, CT and Atlanta, GA. Participants were recruited over 40 months between 2001 and 2005 from two university affiliated obstetrics and gynecology clinics that served mostly low-income, minority women. The purpose of the RCT was to compare women receiving group prenatal care versus standard individual prenatal care and reduce reproductive and HIV risks among young mothers. Details regarding the original study are provided in previous research evaluating the effect of the intervention [10, 11].

Eligible participants were pregnant women at <24 weeks of gestation, between the ages of 14 and 25 years, with no severe medical problems (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, HIV), and who agreed to be randomized. Of the 1,542 eligible women, 1,047 enrolled in the study (participation rate, 68 %) and provided informed consent. Those who agreed to participate were more likely to be Black, older, and further along in their pregnancies than those who refused to participate. The study was conducted from September 2001 to December 2004. All women provided informed consent for study participation. Study procedures adhered to the ethical principles of institution review boards and human investigations committees at Yale University and Emory University.

Participants completed structured interviews by “audio computer-assisted self-interviewing” (A-CASI) on laptop computers with assistance from trained study staff. A-CASI interviews were performed at baseline, which was during the second trimester; and follow-up interviews were conducted in the third trimester, 6 months postpartum, and 12 months postpartum. Participants were paid $20 for each interview.

The current study utilized baseline and 6 and 12 months postpartum data. The IPV module was implemented during the postpartum assessments only. Of the 1,047 study participants, 734 (70.4 %) completed the 6 and 12 months postpartum surveys including the IPV module. There were no significant differences between participants included in these analyses and those excluded (n = 313) on key demographic variables.

Postpartum Intimate Partner Violence

The main independent variable of interest was IPV at 6 and 12 months after childbirth. Adapted from the Conflict Tactics Scale, three items were used to query postpartum young mothers about their experience of emotional IPV (i.e., insult, put down, swear, threaten), physical IPV (i.e., push, grab, slap, kick, punch, beat up, burn, choke), and sexual IPV (i.e., forced sex, forced sexual acts) during the last 6 months by their current partner. Responses were measured on a five-point scale from 1 = never to 5 = very often, and recoded as binary following previous research [7].

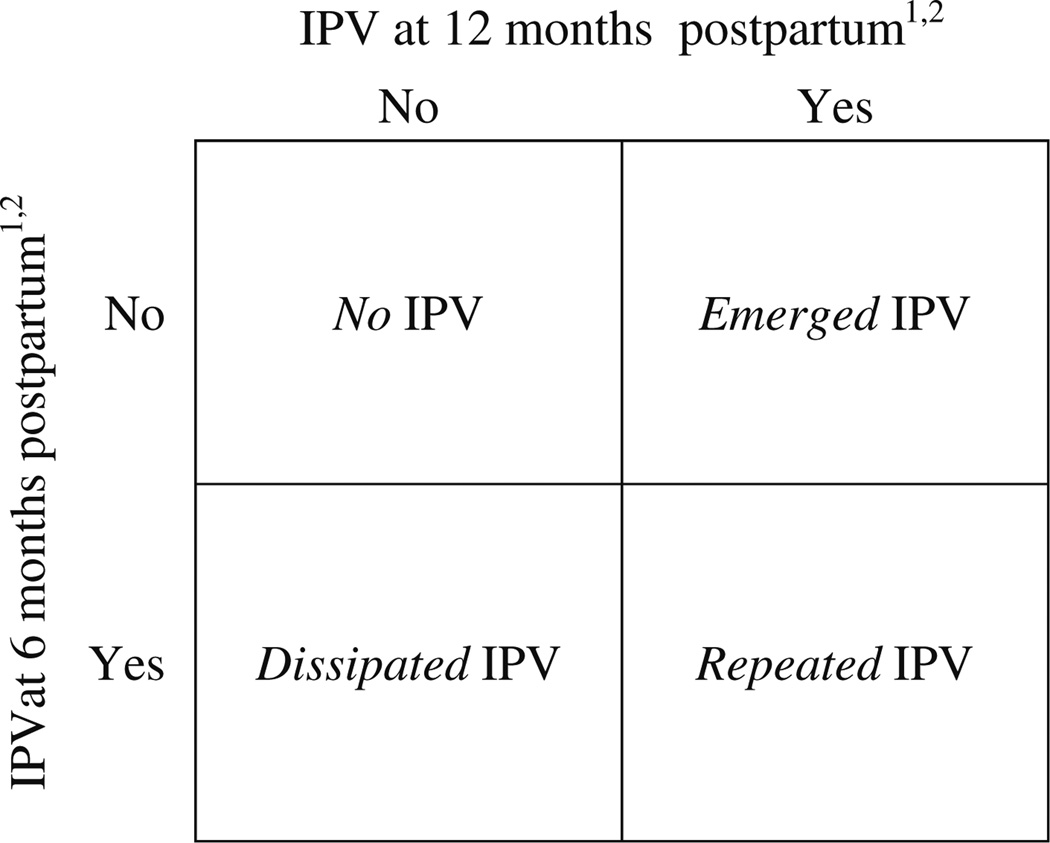

Two variables were created describing young mothers who experienced “any postpartum IPV” (i.e., emotional, physical, and/or sexual) at 6 and 12 months postpartum by their current partner. These two variables were used to define four mutually exclusive groups describing all possible postpartum IPV patterns reported by young mothers (Fig. 1). IPV that occurred between 6 and 12 months postpartum, not 0–6 months postpartum was defined as “emerged IPV”. IPV that occurred between 0 and 6 months postpartum, but not 6 and 12 months postpartum was defined as “dissipated IPV”. IPV reported at both postpartum time periods was defined as “repeated IPV”. Young mothers who did not experience IPV at both postpartum time points made up the “no IPV” group. The names of these IPV patterns were drawn from similar variables constructed by Koenig et al. [12] in their longitudinal analysis of IPV.

Fig. 1.

Definition of postpartum intimate partner violence (IPV) groups. Notes: 1Refers to postpartum IPV reported during the last 6 months; 2Includes experience of emotional, physical, and/or sexual postpartum IPV

The grouping together of emotional, physical, and sexual IPV at each time point when defining “any IPV” postpartum is consistent with IPV measures used in the literature [13, 14]. This is also justified since women are simultaneously experiencing all IPV types over the given time period.

Postpartum Health Risk Measures

Psychological, sexual, and parent/infant health risks were examined at 6 and 12 months postpartum. Psychological health was captured by measures of stress and depression. Stress was assessed by Cohen’s perceived stress scale, which measures the degree to which situations in one’s life are considered stressful [15]. We used a 10-item adaptation of this scale, which demonstrated good internal consistency at 6 months (α = 0.83) and 12 months (α = 0.86) postpartum. Responses referred to the past one month and ranged from 1 = never to 5 = very often. Higher scores indicated more perceived stress.

Depression was measured with the Center for Epidemiological Studies–Depression (CES-D) scale [16]. The original scale includes 20 items that describe symptoms and behaviors characteristic of depressive disorder. For the present study, five psycho-physiologic items were not included to avoid conceptual overlap between depressive symptoms and symptoms of pregnancy (e.g., “I did not feel like eating/my appetite was poor”; “My sleep was restless”; and “I could not get going”). On all other 15 items, respondents indicated how often they experienced each item during the past week on a four-point scale: 0 = <1 day, 1 = 1–2 days, 2 = 3–4 days, and 3 = 5–7 days. Similar modification of this scale has been applied in previous research on pregnant adolescent patients with good reliability [17], which was also found in our analyses at 6 (α = 0.87) and 12 months (α = 0.86) postpartum.

Sexual health risks examined were young mothers’ reported fear of condom negotiation and condom use. The fear of condom negotiation measure consisted of seven items and assessed participants’ fears about their partners’ reactions if participants attempted to negotiate condom use (e.g., “I am worried that if I talked about using condoms my sex partner/boyfriend would leave me”). Responses referred to the past 6 months and ranged from 1 = never to 5 = always. Higher scores indicated more fear of negotiating condom use. The measure has been associated with risky sexual behavior among adolescents [18] and its internal consistency in our analyses was good at 6 months (α = 0.90) and 12 months (α = 0.89) postpartum.

Condom use was calculated as the average estimated percentage condom use across all sex acts in the past 30 days. Individuals who did not have any sexual partners were coded as having zero unprotected sexual acts. Condom use has been coded this way in previous research [11].

Parent/infant health outcomes were assessed by measures of infant sleeping problems and parental stress. The infant sleeping problems scale was drawn from the infant dysregulation domain of the infant toddler social emotional assessment (ITSEA) [19]. This scale consists of five items and assesses typical sleeping behavior and potential problematic sleeping behavior in very young children (e.g., “My baby wakes up screaming or crying and does not respond to adults for a few minutes”). Response options referred to the last 4 weeks and were 0 = not at all true, 1 = somewhat true, 2 = very true. Higher scores indicated more problems with infant sleeping. The internal consistency of the scale was adequate at 6 months (α = 0.65) and 12 months (α = 0.66) postpartum.

Parental stress was assessed using the short-form of the parental stress index which consists of 24 items [20]. The index assesses parental sense of competency and feelings of isolation as a parent (e.g., “My child rarely does things that make me feel good”; “Most times I feel like my child doesn’t like me and doesn’t want to be close to me”). Responses were on a five point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree except one item which asked respondents to rate how good of a parent they felt they were from 1 = not very good parent to 5 = a very good parent. Higher scores indicated more parental stress and dysfunction. The measure demonstrated good internal consistency at 6 months (α = 0.88) and 12 months (α = 0.89) postpartum.

Covariates

Age, education, race/ethnicity, employment, parity, and history of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) reported at baseline along with relationship status information reported during the postpartum period were included as covariates. Relationship status at 6 and 12 months postpartum was used to capture the following relationship dynamics: relationship dissolution, relationship formation, relationship with the same partner, relationship with a different partner, and no relationship. Participation in the intervention and control group was controlled for in these analyses.

Data Analysis

Descriptive findings are reported on study outcomes and postpartum IPV rates by type of violence and postpartum time point. McNemar test was performed to examine differences in postpartum IPV prevalence rates at 6 and 12 months postpartum. Differences in covariates were compared among postpartum IPV groups using the χ2 test. Comparisons at P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Repeated measures ANCOVA was employed to measure changes in health risks over time by postpartum IPV group (i.e., emerged, dissipated, repeated, and no postpartum IPV groups). When data are available at two time points for continuous outcomes, this is the appropriate method. The main effect of group tested whether marginal mean health outcome levels averaged over the 6 and 12 months postpartum assessments differed by postpartum IPV group. The interaction effect of group × time tested whether the change in marginal mean postpartum health outcome levels at 6 and 12 months postpartum differed by postpartum IPV group. For significant interaction effects, the marginal means of selected health outcomes for each postpartum IPV group were plotted at 6 and 12 months postpartum. The main and interaction effects were adjusted for age, education, race, STD history, employment, relationship status, and intervention group.

Results

The prevalence of any postpartum IPV at either 6 or 12 months after childbirth was 33.8 % (n = 248). Postpartum IPV prevalence rates significantly increased from 17.9 % (n = 131) at 6 months to 25.3 % (n = 186) at 12 months after childbirth (McNemar, P < 0.001).

Postpartum IPV at 6 months after childbirth was 16.8 % emotional IPV, 7.6 % physical IPV, and 3.3 % sexual IPV. At 12 months after childbirth, postpartum IPV was 24.9 % emotional IPV, 8.5 % physical IPV, and 4.0 % sexual IPV. Emotional postpartum IPV prevalence significantly increased from 6 to 12 months postpartum (McNemar, P < 0.001), physical (McNemar, P = 0.53) and sexual (McNemar, P = 0.47) postpartum IPV rates did not significantly increase though a rising trend in prevalence was observed for both IPV types. Physical and sexual IPV was 2.5 % at 6 months and 3.1 % at 12 months postpartum. Among young women reporting sexual or physical IPV, 87 % experienced concurrent emotional IPV at 6 months postpartum and 96 % experienced concurrent emotional IPV at 12 months postpartum. This substantial overlap supported grouping IPV types together when defining postpartum IPV. Among young mothers reporting postpartum IPV, for 47.2 % (n = 117) IPV emerged, for 25.0 % (n = 62) IPV dissipated, and for 27.8 % (n = 69) IPV repeated from 6 months to 12 months postpartum.

The majority of young mothers in the study sample were Black (76.8 %), 49.2 % were adolescents (i.e., 14–19 years), 50.8 %were young adults (i.e., 20–25 years), and almost half had not completed high school. These age ranges for defining adolescent and young adults are consistent with previous studies [21, 22]. At baseline, over a third of young mothers already had at least one child and 51 % had a prior history of STDs. No significant differences by age, race, education, parity, and STD history were observed by postpartum IPV group. Intervention group participation did not influence postpartum IPV patterns (results not shown).

Main Effects of Postpartum IPV Groups

Table 1 shows that the overall marginal means of all outcomes differed significantly by postpartum IPV group controlling for age, education, race/ethnicity, employment, parity, STD history, relationship status, and intervention group. A main effect of group was observed with respect to mean levels of stress (F = 27.49, P < 0.001), depression (F = 22.31, P < 0.001), fear of condom negotiation (F = 20.88, P < 0.001), condomuse (F = 6.87, P < 0.001), infant sleeping problems (F = 4.73, P < 0.01), and parental stress (F = 29.99, P < 0.001). Compared to all other IPV groups, young mothers in the repeated postpartum IPV group had the highest mean stress, depression, fear of condom negotiation, infant sleeping problems, and parental stress scores and the lowest average percent condom use. Mean outcome levels ranked second worst among young mothers in the emerged postpartum IPV group.

Table 1.

Main effect of postpartum intimate partner violence (IPV) patterns by postpartum psychological, sexual, and parent/infant health risks (n = 734)

| Postpartum health risks | Postpartum IPV patterns | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Emerged IPVa,b,f Marginal mean (SE) |

Dissipated IPVa,c,f Marginal mean (SE) |

Repeated IPVa,d,f Marginal mean (SE) |

No IPVa,e,f Marginal mean (SE) |

Main effect Group P value |

|

| Psychological | |||||

| Stress | 19.2 | 18.6 | 20.2 | 15.0 | F = 27.49 |

| (0.57) | (0.79) | (0.74) | (0.29) | P < 0.001 | |

| Depression | 13.3 | 11.3 | 14.0 | 8.8 | F = 22.31 |

| (0.64) | (0.88) | (0.83) | (0.31) | P < 0.001 | |

| Sexual | |||||

| Fear of condom negotiation | 9.2 | 8.6 | 9.8 | 7.6 | F = 20.88 |

| (0.25) | (0.34) | (0.32) | (0.12) | P < 0.001 | |

| Condom use | 48.3 | 60.9 | 44.3 | 60.7 | F = 6.87 |

| (3.36) | (4.70) | (4.40) | (1.64) | P < 0.001 | |

| Parent/infant | |||||

| Infant sleeping problems | 2.3 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 1.9 | F = 4.73 |

| (0.15) | (0.21) | (0.20) | (0.07) | P = 0.003 | |

| Parental stress | 48.7 | 47.4 | 53.6 | 41.7 | F = 29.99 |

| (1.06) | (1.48) | (1.40) | (0.52) | P < 0.001 | |

Outcome averaged over 6 and 12 months postpartum time points

Emerged IPV occurred from 6 to 12 months postpartum, not 0–6 months postpartum

Dissipated IPV occurred from 0 to 6 months postpartum, not 6–12 months postpartum

Repeated IPV occurred at both postpartum time periods, 0–6 and 6–12 months

No IPV did not occur at both postpartum time points

Controlling for age, education, race/ethnicity, employment, parity, STD history, relationship status, intervention group

Interaction Effect of Postpartum IPV Groups Over Time

Table 2 shows changes in health risks among young mothers who experienced different postpartum IPV patterns over the postpartum period controlling for age, education, race/ethnicity, employment, parity, STD history, relationship status, and intervention group. In Fig. 2, plots of the marginal means for selected psychological, sexual, and parent/infant outcomes by postpartum IPV group are shown.

Table 2.

Interaction effect of postpartum intimate partner violence (IPV) groups on postpartum psychological, sexual, and parent/infant health risks at 6 and 12 months after childbirth (n = 734)

| Postpartum health risks |

Postpartum IPV groups | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emerged IPVa,e,f | Dissipated IPVb,e,f | Repeated IPVc,e,f | No IPVd,e,f | Interaction effect |

|||||

| 6 months Marginal mean (SE) |

12 months Marginal mean (SE) |

6 months Marginal mean (SE) |

12 months Marginal mean (SE) |

6 months Marginal mean (SE) |

12 months Marginal mean (SE) |

6 months Marginal mean (SE) |

12 months Marginal mean (SE) |

Group × time P value |

|

| Psychological | |||||||||

| Stress | 18.4 | 19.9 | 19.2 | 18.0 | 19.8 | 20.5 | 15.0 | 14.9 | F3,734 = 3.71 |

| (0.6) | (0.6) | (0.9) | (0.9) | (0.8) | (0.8) | (0.3) | (0.3) | P < 0.01 | |

| Depression | 12.2 | 14.4 | 12.2 | 10.4 | 13.8 | 14.3 | 8.8 | 8.7 | F3,734 = 5.90 |

| (0.7) | (0.7) | (1.0) | (1.0) | (0.9) | (0.9) | (0.3) | (0.3) | P < 0.001 | |

| Sexual | |||||||||

| Fear of condom negotiation |

8.7 | 9.6 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 9.8 | 9.8 | 7.7 | 7.6 | F3,734 = 3.65 |

| (4.2) | (4.8) | (4.3) | (3.7) | (5.2) | (5.7) | (2.5) | (1.8) | P = 0.01 | |

| Condom use | 54.5 | 42.0 | 56.8 | 64.9 | 51.4 | 37.3 | 61.7 | 59.8 | F3,734 = 4.31 |

| (4.0) | (4.0) | (5.5) | (5.5) | (5.2) | (5.1) | (1.9) | (1.9) | P < 0.01 | |

| Parent/infant | |||||||||

| Infant sleeping problems |

2.2 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | F3,734 = 2.74 |

| (0.17) | (0.17) | (0.24) | (0.24) | (0.23) | (0.23) | (0.09) | (0.08) | P < 0.05 | |

| Parental stress | 48.2 | 49.2 | 48.7 | 46.1 | 54.8 | 52.5 | 43.1 | 40.3 | F3,734 = 3.78 |

| (1.2) | (1.2) | (1.6) | (1.7) | (1.5) | (1.6) | (0.57) | (0.60) | P < 0.01 | |

Emerged IPV occurred from 6 to 12 months postpartum, not 0–6 months postpartum

Dissipated IPV occurred from 0 to 6 months postpartum, not 6–12 months postpartum

Repeated IPV occurred at both postpartum time periods, 0–6 and 6–12 months

No IPV did not occur at both postpartum time points

Boldface indicates significant changes over time in outcome (P < 0.05)

Controlling for age, education, race/ethnicity, employment, parity, STD history, relationship status, intervention group

Fig. 2.

Plots of marginal mean psychological, sexual, and parent/ infant postpartum health risks by postpartum intimate partner violence (IPV) groups at 6 and 12 months postpartum (n = 734). a Stress1,2. b Condom use1,2. c Infant sleeping problems1,2. Notes: 1Solid lines indicate significant changes over time in outcome (P < 0.05) and dashed lines indicate non-significant changes over time in outcome (P > 0.05); 2controlling for age, education, race/ ethnicity, employment, parity, STD history, relationship status, intervention group

Significant group × time interactions were observed for all outcomes—stress (F = 3.71, P < 0.01), depression (F = 5.90, P < 0.001), fear of condom negotiation (F = 3.65, P < 0.01), condom use (F = 4.31, P < 0.01), infant sleeping problems (F = 2.74, P < 0.05), and parental stress (F = 3.78, P < 0.01). Among young mothers for whom postpartum IPV emerged postpartum, their mean levels of stress (P < 0.01), depression (P < 0.001), and fear of condom negotiation (P < 0.01) increased, while their average percent condom use decreased (P < 0.01). When IPV dissipated postpartum, mean depression scores for young mothers decreased (P < 0.05). While young mothers who experienced repeated IPV postpartum reported decreased condom use (P < 0.01) and increased infant sleeping problems (P < 0.05). Young women reporting no IPV postpartum exhibited decreased parental stress (P < 0.001). The effect of the postpartum IPV groups on the study outcomes when examined by IPV type (i.e., emotional and physical/sexual IPV) and frequency yielded similar trends (results not shown).

Discussion

The study findings showed that IPV is substantive during the postpartum period and contributes to young mothers’ postpartum health risks. The prevalence and trend of postpartum IPV observed in this study supports and differs from previous research. Harrykissoon et al. [5] reported physical IPV prevalence was 16.1 % at 6 months and 17.7 % at 12 months postpartum among adolescent mothers. From 3 to 24 months postpartum, physical IPV significantly decreased in their study. In our study, physical IPV rates were 7.6 % at 6 months and 8.5 % at 12 months postpartum and did not significantly change during this period. Scribano et al. [23] found that among US, adult, low-income mothers, 12.7 % experienced physical IPV at 12 months after childbirth. Other studies on postpartum IPV are among non-US, adult, women. They show physical postpartum IPV rates ranging from 1.8 to 2.2 % [14, 24], that younger women are at greater risk of postpartum IPV [25], and postpartum IPV (i.e., physical and emotional) increased from 8 to 33 months after childbirth [24]. Variability in these postpartum IPV estimates may be due to the duration examined after child birth, sample size, age range, and subject recruitment.

This study’s longitudinal analyses demonstrated that postpartum IPV was associated with psychological, sexual, and parent/infant postpartum health risks among young mothers. These associations varied depending on the pattern of IPV experienced. From 6 to 12 months after childbirth, postpartum health risks significantly increased when postpartum IPV repeated or emerged and significantly decreased when postpartum IPV dissipated. Repeated postpartum IPV was positively associated with infant sleeping problems, suggesting that maternal IPV has the potential to impact infants. Postpartum emerged IPV was associated with 4 outcomes compared to repeated IPV, associated with 2 outcomes. It is possible a greater number of changes in health risks were observed when postpartum IPV emerged, because differences in outcomes could be more easily detected when IPV was not present at a time point. Campbell et al. [26] found repeated IPV was associated with worsening outcomes (e.g., depression and stress) compared to less frequent IPV. However, this study’s sample was high-risk including only women reporting IPV at baseline; therefore the influence of emerged IPV was not examined.

Our study findings on postpartum IPV and depression support abundant research on this topic [7]. Similar to our findings, a longitudinal study on adult women found that depression scores decreased when IPV discontinued [26]. Little research has examined stress after pregnancy especially among young women [1]. Our results showing that perceived stress significantly increased when postpartum IPV emerged complements research demonstrating that IPV is associated with posttraumatic stress and anxiety disorders among young adult and adult women [27].

Study results on reduced condom use and increased fear of condom negotiation when postpartum IPV repeated and/or emerged support previous research on IPV and contraceptive use. Coker et al. [28] found partner violence was associated with inconsistent condom use among women 18–29 years of age. In a qualitative study, abused women aged 15–20 years reported that male partners promoted pregnancy by verbal pressure, birth control sabotage, and forced sex without condoms [29].

Study findings on the association between infant sleeping problems and emerged postpartum IPV support research on IPV and infant difficulties [9]. Associations between IPV and parental stress were not observed in our study. IPV and parental stress have not been widely examined in the literature, but Huth-Bocks et al. [6] found that IPV severity was also not associated with parental stress among adult, battered women. Other research though has shown that IPV and parental stress were associated with child maltreatment.

Programmatic implications of the study findings are that IPV prevention is pertinent during the postpartum period and may reduce young mothers’ postpartum health risks. In this study, 47 % of postpartum IPV emerged suggesting early IPV screening may facilitate prevention. Recently, IPV screening for young girls throughout their reproductive cycle was recommended by the Institute of Medicine and American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists [30]. In 2012, the US Preventive Services Task Force reported that screening asymptomatic females for IPV may provide benefits and pose minimal risks. Because the Affordable Care Act calls for insurance coverage for IPV screening and counseling, all primary care physicians are advised to screen female patients 12 years of age or older [31].

Successful IPV reduction programs among adult women have utilized screening and behavioral counseling through multiple sessions during and after pregnancy [32]. Other models shown to reduce postpartum IPV are home visitation programs by paraprofessionals or nurses [33, 34]. Group-based models of prenatal care, such as Centering Pregnancy, are an additional avenue to prevent IPV before childbirth [11].

A study strength was documenting the prevalence of IPV after childbirth which has not been extensively examined in the literature, especially among young mothers. Longitudinal data available on IPV and multiple health outcomes strengthened the associations examined. An inherent limitation of IPV studies, including this one, was use of self-reported measures. The findings may not be generalizable to young women in the US, since the data were from a RCT and clinic-population. The study also lacked information on partners and couples such as partners’ behaviors and relationship quality.

Future research should utilize population-based study designs and examine of IPV after pregnancy, include couples-level information, and assess potential differences by age groups (e.g., adolescent and young adult women). This may help craft more effective IPV prevention programs and reduce postpartum health risks among young women as they transition to motherhood.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Yale Centering Pregnancy Research Group for their feedback on this manuscript. This project was supported by Grant R01 MH/HD61175 and Award Number T32MH020031 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Additional support was provided by the Yale Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (NIMH P30MH062294). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Alpna Agrawal, Email: Alpna.A.Agrawal@uth.tmc.edu, School of Medicine, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA.

Jeannette Ickovics, School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA; Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA.

Jessica B. Lewis, School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA.

Urania Magriples, School of Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA.

Trace S. Kershaw, School of Public Health, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA.

References

- 1.Kingston D, Heaman M, Fell D, et al. Comparison of adolescent, young adult, and adult women’s maternity experiences and practices. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1228–e1237. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abramsky T, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C, et al. What factors are associated with recent intimate partner violence? Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catalano S. Intimate partner violence in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2007. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/ipvus.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailey BA. Partner violence during pregnancy: Prevalence, effects, screening, and management. International Journal of Women’s Health. 2010;2:183. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s8632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harrykissoon S, Rickert V, Wiemann C. Prevalence and patterns of intimate partner violence among adolescent mothers during the postpartum period. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:325. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.4.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor CA, Guterman NB, Lee SJ, et al. Intimate partner violence, maternal stress, nativity, and risk for maternal maltreatment of young children. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:175–183. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.126722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA, Kaufman JS, et al. Intimate partner violence against adult women and its association with major depressive disorder, depressive symptoms and postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Science and Medicine. 2012;75:959–975. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Decker MR, Miller E, McCauley HL, et al. Recent partner violence and sexual and drug-related STI/HIV risk among adolescent and young adult women attending family planning clinics. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2013 doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051288. sextrans-2013-051288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke JG, Lee L-C, O’Campo P. An exploration of maternal intimate partner violence experiences and infant general health and temperament. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2008;12:172–179. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0218-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, et al. Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;110:330. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275284.24298.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kershaw TS, Magriples U, Westdahl C, et al. Pregnancy as a window of opportunity for HIV prevention: Effects of an HIV intervention delivered within prenatal care. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99:2079. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.154476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koenig L, Whitaker D, Royce R, et al. Physical and sexual violence during pregnancy and after delivery: A prospective multistate study of women with or at risk for HIV infection. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1052. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charles P, Perreira KM. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy and 1-year post-partum. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:609–619. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woolhouse H, Gartland D, Hegarty K, et al. Depressive symptoms and intimate partner violence in the 12 months after childbirth: A prospective pregnancy cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2012;119:315–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuckerman B, Amaro H, Bauchner H, et al. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: Relationship to poor health behaviors. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1989;160:1107. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sionean C, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. Psychosocial and behavioral correlates of refusing unwanted sex among African-American adolescent females. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Jones SM, et al. The infant–toddler social and emotional assessment (ITSEA): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:495–514. doi: 10.1023/a:1025449031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abidin R. Parenting stress index: A measure of the parent–child system. In: Zalaquett CP, Woods RJ, editors. Evaluating stress: A book of resources. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press; 1997. pp. 277–291. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Escoto KH, Laska MN, Larson N, et al. Work hours and perceived time barriers to healthful eating among young adults. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2012;36:786–796. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.36.6.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein DA, Gildengorin G, Mosher P, et al. Adolescent caesarean delivery in the US military health care system. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 2011;25:74–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scribano PV, Stevens J, Kaizar E. The effects of intimate partner violence before, during, and after pregnancy in nurse visited first time mothers. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2012;17:307–318. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0986-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowen E, Heron J, Waylen A, et al. Domestic violence risk during and after pregnancy: Findings from a British longitudinal study. BJOG-An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2005;112:1083–1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rådestad I, Rubertsson C, Ebeling M, et al. What factors in early pregnancy indicate that the mother will be hit by her partner during the year after childbirth? A nationwide Swedish survey. Birth. 2004;31:84–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.00285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell J, Soeken K. Women’s responses to battering over time: An analysis of change. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1999;14:21. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caldwell JE, Swan SC, Woodbrown VD. Gender differences in intimate partner violence outcomes. Psychology of Violence. 2012;2:42. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coker AL. Does physical intimate partner violence affect sexual health? A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2007;8:149–177. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller E, Decker MR, Reed E, et al. Male partner pregnancy-promoting behaviors and adolescent partner violence: Findings from a qualitative study with adolescent females. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2007;7:360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Devi S. US guidelines for domestic violence screening spark debate. The Lancet. 2012;379:506. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60215-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liebschutz JM, Rothman EF. Intimate-partner violence: What physicians can do. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:2701–2703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1204278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson HD, Bougatsos C, Blazina I. Screening women for intimate partner violence. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;156:796–808. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharps PW, Campbell J, Baty ML, et al. Current evidence on perinatal home visiting and intimate partner violence. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing: JOGNN/NAACOG. 2008;37:480. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2008.00267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bair-Merritt MH, Jennings JM, Chen R, et al. Reducing maternal intimate partner violence after the birth of a child: A randomized controlled trial of the Hawaii Healthy Start Home Visitation Program. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2010;164:16. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]