Abstract

Context

The scientific study of yoga requires rigorous methodology. This review aimed to systematically assess all studies of yoga interventions to: (1) determine yoga intervention characteristics; (2) examine methodologic quality of the subset of RCTs; and (3) explore how well these interventions are reported.

Evidence acquisition

Searches were conducted through April 2012 in PubMed, PsycInfo, Ageline, and Ovid’s Alternative and Complementary Medicine database using the text term yoga, and through handsearching five journals. Original studies were included if the intervention: (1) consisted of at least one yoga session with some type of health assessment; (2) targeted adults age ≥18 years; (3) was published in an English language peer–reviewed journal; and (4) was available for review.

Evidence synthesis

Of 3,062 studies identified, 465 studies in 30 countries were included. Analyses were conducted through 2013. Most interventions took place in India (n=228) or the U.S. (n=124), with intensity ranging from a single yoga session up to two sessions per day. Intervention lengths ranged from one session to 2 years. Asanas (poses) were mentioned as yoga components in 369 (79%) interventions, but were either minimally or not at all described in 200 (54%) of these. Most interventions (74%, n=336) did not include home practice. Of the included studies, 151 were RCTs. RCT quality was rated as poor.

Conclusions

This review highlights the inadequate reporting and methodologic limitations of current yoga intervention research, which limits study interpretation and comparability. Recommendations for future methodology and reporting are discussed.

Introduction

Accumulating evidence suggests that yoga promotes general health and well-being, and that it can be beneficial for individuals with a range of physical health problems. The National Health Interview Surveys demonstrate a significant increase in the use of yoga among the general population in response to various health conditions.1 The word yoga “represents a body of practices…[referring] to the discipline of aligning the mind and body for spiritual goals.”2 Although there is a wide variety of different styles of yoga, many are based on Patanjali’s eight limbs of yoga, outlined in the Yoga Sutras, which describe the yogic system.3 Traditionally, the eight stages, or “limbs,” of yoga are tenets for the yogi to follow as he or she practices external interactions, refines the process of turning inward and cultivating greater awareness, and deepens a meditative spiritual connection.

Research on yoga therapy is also proliferating, including the conduct of RCTs in a variety of populations.4–7 Because yoga is a vast and heterogeneous set of activities,3 different studies implement yoga in very different ways, thus reflecting the richness and diversity of yogic approaches. Yet, this heterogeneity also makes the comparison of findings across studies difficult, and limits researchers’ ability to understand the mechanisms by which yoga affects physical and mental well-being.

Currently, yoga interventionists lack valid methods and tools to describe their interventions. Studies of yoga often include some combination of the basic components of yoga according to Patanjali’s eight limbs (e.g., asanas, breath work, and meditation), but the specific details regarding these components are often not provided in the published descriptions.7 Although some systematic reviews examining the efficacy of yoga interventions have concluded that yoga is beneficial for health,6,7 many other reviews have noted inconsistent or inconclusive results. A number of authors have suggested that the heterogeneity of the studied interventions, owing to the many different types of yoga practiced based on each teacher’s training and philosophy, may account for inconsistent findings.8,9 In a recent review of yoga literature as part of an effort to develop standard descriptions of yoga intervention protocols, Sherman10 adapted previous work on acupuncture protocols to identify domains that should be addressed in any yoga efficacy study. These domains included style, dose and delivery of yoga, components of the yoga intervention, specific class sequences, modifications, selection of instructors, facilitation of home practice, and measurement of intervention fidelity over time.10 There is some suggestion of a dose-response effect for yoga,11 but without quantification of the various components, this issue is difficult to examine. Many have argued that yoga should be described in more detail, in terms of frequency, intensity, and duration of sessions to allow for determination of exercise dose-response.8

Along with heterogeneity among interventions and the lack of adequate reporting, many published yoga studies have had weak study designs. Thus, most literature reviews conclude that the evidence for yoga’s efficacy, although suggestive, is not definitive and that more rigorous research is needed.9 Given this heterogeneity, conducting a systematic literature review of the effectiveness of all yoga interventions was not possible. Instead, a systematic scoping literature review, a specific form of systematic review methodology, was undertaken because a scoping review can determine the size and nature of the evidence base for yoga interventions, help identify gaps in the yoga intervention literature, and make recommendations for future primary research in this area.13 Moreover, the goal of scoping reviews is not to synthesize evidence or answer clinical questions about yoga’s effectiveness.13

Thus, this systematic scoping literature review was undertaken to answer the three following research questions: (1) What are the characteristics of yoga interventions in the literature? (2) What is the methodological quality of the subset of interventions that are RCTs? and (3) How well are yoga interventions reported in the literature according to elements of practice, duration, frequency, location, environment, additional yoga intervention emphases, and teacher experience? Information from this scoping review will allow yoga researchers to develop protocols for future interventions that build on the evidence base described here, and address the current gaps in yoga intervention studies.

Methods

Search Strategy

The review protocol followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for conducting and reporting items for systematic reviews.12 All 27 items of the PRISMA checklist are included in this report, except for quantitative synthesis of results, as quantitative data on outcomes was not collected in this review. Two authors searched four electronic databases, PsycInfo, Ovid’s Alternative and Complementary Medicine database, AgeLine, and PubMed, using the text term yoga, from the inception of the database until the end review date of April 27, 2012. Yoga was defined as consisting of at least one of Patanjali’s eight limbs.3 In addition, the electronic table of contents of five key journals were handsearched, selected because of their prominence in the electronic database search results: Archives of Internal Medicine, BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, International Journal of Yoga, and Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine.

Studies located by the search strategy were coded for inclusion using a checklist created in Microsoft Excel, developed from guidelines of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) at the University of York.13 The reliability of this checklist was tested by two of the authors on a subsample of 25 abstracts. If the abstracts did not provide enough information, the full text of the article was obtained for review. Cohen’s κ for the reliability of this test was 0.91, considered a very high inter-rater agreement.14 One author coded the remaining studies for inclusion.

Inclusion Criteria and Acquisition of Included Articles

Studies were selected for review if they met the four following criteria: (1) the study consisted of a yoga intervention, defined as providing at least one yoga session to participants and measuring any outcomes with at least a pre- and post-test; (2) participants in the intervention were aged ≥18 years; (3) the published paper was written in English; and (4) the full text of the article was available for review. If an article was not available in electronic format, it was purchased through one of two university library centers. If a university library was unable to obtain the article, one of the authors wrote to the first author requesting a reprint of the article.

Quality Assessment

A quality assessment of yoga intervention RCTs was undertaken to provide more information about the quality of this research subset on what is viewed as the highest level of evidence.15 The methodologic quality of these RCTs was assessed using seven categories of potential bias, as defined by the CRD:

Was the method used to generate random allocations adequate?

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Were the groups similar at the outset of the study in terms of prognostic factors, such as severity of disease?

Were the care providers, participants, and outcome assessors blind to treatment allocation? If any of these people were not blinded, what might be the likely impact on the risk of bias for each outcome?

Were there any unexpected imbalances in dropouts between groups? If so, were they explained or adjusted for?

Is there any evidence to suggest that the authors measured more outcomes than they reported?

Did the analysis include an intention to treat analysis? If so, was this appropriate and were appropriate methods used to account for missing data?13

Two authors rated each of these seven categories with a “yes adequate description” (e.g., high quality) or “not adequate description” rating (e.g., low quality). If no information was provided in the study for a methodologic category, this was rated as “no information available.” When disagreements occurred, these were resolved through discussion and eventual consensus.

Data Collection

Data from studies meeting the inclusion criteria were extracted into categories developed from Sherman10 and the team’s review of the yoga literature, a process used in previous systematic literature reviews.16 After discussion and consensus among study team members, 16 data extraction categories were created: first author, country of publication, year of publication, study design, style of yoga, asanas described, time in asanas described, study setting, frequency of yoga session, duration of yoga session, length of intervention, home practice, outcomes measured, comparison groups, additional emphases of the yoga intervention (other than asanas), and yoga instructor training and experience. Two authors pilot-tested this data extraction checklist prior to its use in the study, and disagreements in data extraction were resolved through discussion. The comparison group category is discussed in a separate paper currently in development.

Data Analysis

Descriptive information from the data extraction checklist was organized in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, and summary counts of each of the coding categories were performed. A full list of references is included as Appendix 1. Data are summarized and described narratively in the text, Table 2, and Appendix 2. Descriptive analyses were performed between May 2012 and December 2013.

Table 2.

Summary information from included studies, n=465

| Country of study(n) |

Years published |

Study design |

Styles of yoga |

Study settings |

Frequency of yoga session |

Duration of yoga session |

Length of yoga intervention |

Home practice |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India (228) | 1983– 2012 |

RCT- 64 Obs- 161 Case- 3 |

N/A-48 Hatha-73 Yogic breathing- 24 Yogic meditation- 20 SKY-16 Integrated- 14 Nidra-6 Kapalbathi- 7 Vivekenand a-5 Yoga Relaxation- 3 Sahaja-5 Patanjali-2 Viniyoga-1 Kundalini-1 Tibetan-1 Mindfulness -1 Iyengar-1 |

N/A-45 Residential yoga center or institute- 52 Laboratory- 46 Hospital clinic-19 University campus-12 Yoga health clinic-19 Hospital inpatient-7 Psychiatric facility-3 Community center-4 Home-6 Workplace- 3 Nursing home-2 Military base-1 Yoga studio-1 Refugee camp-1 Outdoor lawn-1 |

N/A-36 1 session/day- 62 2 sessions/day- 18 4 sessions/day- 1 5 sessions/day- 1 1 session/week -4 2 sessions/wee k-5 3 sessions/wee k-12 4 sessions/wee k-3 5 sessions/wee k-13 6 sessions/wee k-17 1 session-28 2 sessions-5 4 sessions-2 7 sessions-1 6 days-1 15 sessions-1 |

N/A-38 15 seconds- 2 1 minute- 2 2 minutes- 1 3 minutes- 1 5 minutes- 3 60 minutes- 59 30 minutes- 26 90 minutes- 16 45 minutes- 9 75 minutes- 2 15 minutes- 3 18 minutes- 1 20 minutes- 14 22 minutes 30 seconds- 8 25 minutes- 1 33 minutes- 2 35–36 minutes- 4 40 minutes- 7 50 minutes- 1 2 hours- 3 2.5 hours-5 3–4 hours 4 7 hours- 1 8 hours- 2 |

N/A-10 Once-30 1 day-3 Twice-1 2 days-5 4 days-1 5 days-4 8 days-1 10 days-5 15 days-4 1 week-10 20 days-1 2 weeks-7 3 weeks-7 4 weeks-27 5 weeks-2 6 weeks-11 8 weeks-12 40 days-6 45 days-1 60 days-1 90 days-1 11 weeks-1 12 weeks- 19 14 weeks-1 16 weeks-7 6 months- 16 7 months-1 10 months- 2 1 year-2 2 years-1 |

Yes-53 No or N/A- 175 |

|

U.S. (124) |

1976– 2012 |

RCT- 48 Obs- 73 Case- 3 |

N/A-15 Hatha-33 Iyengar-31 Viniyoga-5 Kundalini-5 Kripalu-6 Anusara-2 Integrated yoga-3 Yogic breathing-2 Nidra-2 Ashtanga-2 Mindfulness -2 Yogic meditation- 2 Yogic breathing-2 Bikram-1 Chair-1 Dru-1 SKY-1 Restorative- 3 Sivenanda-1 Surya-1 Tantric-1 Tibetan-1 Vinyasa-1 Vivekenand a-1 Yogic flying-1 Yoga skills training-1 |

N/A-32 Yoga studio-18 Outpatient hospital setting-17 University campus-12 Laboratory- 13 Home-6 Residential yoga center- 7 Workplace- 5 Psychiatric facility-4 Community center-4 Prison-1 Palliative or cancer care- 2 Gym-1 |

N/A-8 1 session-14 2 sessions-1 3 sessions-2 1 session/day-7 2 sessions/day- 1 3 sessions/day- 1 1 session/week -42 2 sessions/wee k-41 3 sessions/wee k-8 4 sessions/wee k-1 5 sessions/wee k-1 6 sessions/wee k-1 |

N/A-17 2 minutes- 1 12 minutes- 1 15 minutes- 3 20 minutes- 3 25 minutes- 1 30 minutes- 5 45 minutes- 8 50 minutes- 2 60 minutes- 27 70 minutes- 2 75 minutes- 16 90 minutes- 27 2 hours- 7 2.5 hours-2 |

N/A-2 Once-20 Twice-1 Thrice-1 4 days-1 2 weeks-2 3 weeks-1 4 weeks-2 5 weeks-2 6 weeks-9 7 weeks-3 8 weeks-32 9 weeks-1 10 weeks-6 12 weeks- 21 14 weeks-1 15 weeks-2 16 weeks-7 5 months-1 6 months-5 20 weeks-1 1 semester- 1 1 year-1 2 years-1 |

Yes- 46 No or N/A-78 |

|

Australia (8) |

1978– 2012 |

RCT- 5 Obs-3 |

N/A-1 Sahaja-2 Hatha-2 Chair-1 Yogic meditation- 1 Yogic breathing-1 |

N/A-3 Hospital clinic-1 Laboratory- 1 Workplace- 2 University campus-1 |

N/A-1 1 session -2 2 sessions-1 1 session/week -2 2 sessions/wee k-1 2 sessions/day- 1 |

N/A-1 10–20 minutes- 1 15 minutes- 1 60 minutes- 4 90 minutes- 1 |

Once-3 8 weeks-1 10 weeks-1 12 weeks-1 16 weeks-1 9 months-1 |

Yes-1 No-7 |

|

Belgium (1) |

2011 | Obs-1 | Hatha | Psychiatric facility |

1 session | 30 minutes |

Once | No |

| Brazil (8) | 2006– 2012 |

RCT- 3 Obs-5 |

N/A-3 Bhastrika-1 Hatha-2 Yogic relaxation-1 Siddha Samadhi-1 Tibetan-1 |

N/A-6 Laboratory- 1 Military base-1 |

2 sessions-1 1 session/week -1 2 sessions/wee k-3 2 sessions/day- 2 3 sessions/day- 1 |

15 minutes- 1 30 minutes- 1 45–60 minutes- 1 50 minutes- 2 60 minutes- 3 |

Once-1 Twice-2 2 weeks-1 8 weeks-1 12 weeks-1 16 weeks-2 6 months-1 |

Yes-1 No or N/A-7 |

|

Canada (12) |

1983– 2012 |

RCT- 2 Obs- 10 |

N/A-1 Iyengar-3 Hatha-2 Yogic mindfulness -2 SKY-2 Agni-yoga- 1 Kripalu-1 |

N/A-2 Hospital clinic-1 Laboratory- 1 Residential yoga center- 1 University campus-5 Yoga studio-2 |

N/A-2 5 days-1 1 session/week -4 2 sessions/wee k-4 4 sessions/wee k-1 |

N/A-2 45 minutes- 1 60 minutes- 1 75 minutes- 2 90 minutes- 5 10 hours followed by 2 hours-1 |

5 days-1 15 days-1 3 weeks-1 7 weeks-1 8 weeks-4 6–12 weeks-2 10 weeks-1 16 weeks-1 |

Yes-8 No-4 |

|

Czech Republic (5) |

1983– 1991 |

RCT- 1 Obs-4 |

Hatha-4 Kapalbathi- 1 |

Laboratory- 5 |

1 session-2 2 sessions-1 3 sessions-1 28 sessions-1 |

N/A-2 1–1.5 minutes- 1 45–60 minutes- 1 2 hours- 1 |

Once-2 Twice-1 1 day-2 |

No-5 |

|

Denmark (2) |

1999– 2002 |

Obs-2 | Nidra-1 SKY-1 |

Laboratory- 2 |

1 session-2 | 72 minutes- 1 2 hours 45 minutes- 1 |

Once-2 | Yes-1 No-1 |

|

Ethiopia (1) |

2010 | RCT- 1 |

Hatha | Religious mission facility |

1 session/day | 50 minutes |

4 weeks | No |

| France (1) | 2005 | Obs-1 | Ujayii breathing |

Laboratory | 1 session/day | 20–30 minutes |

8 weeks | No |

|

Germany (8) |

1990– 2010 |

RCT- 1 Obs-7 |

N/A-2 Hatha-2 Iyengar-2 SKY-2 |

N/A-2 Laboratory- 3 Residential yoga center- 2 Yoga studio-1 |

N/A-1 1 session-4 2 sessions/wee k-1 1 session/day-2 |

N/A-2 8–12 minutes- 1 10 minutes- 1 40 minutes- 1 90 minutes- 2 2 hours- 1 |

Once-3 5 weeks-1 12 weeks-4 |

No-8 |

|

Indonesia (2) |

2007– 2010 |

Obs-2 | SKY-1 Vivekenand a-1 |

Refugee camps-2 |

1 session/day-2 |

60 minutes- 1 2 hours- 1 |

4 days-1 8 weeks-1 |

No-2 |

| Iran (4) | 2007– 2011 |

RCT- 2 Obs-2 |

N/A-1 Hatha-2 Laughter-1 |

Community center-1 Residential yoga center- 2 University campus-1 |

N/A-2 1 session/day-1 1 session/week -1 |

N/A-1 20 minutes- 1 90 minutes- 2 |

10 sessions-1 2 weeks-1 8 weeks-1 6 months-1 |

No-4 |

| Israel (1) | 2003 | Obs-1 | N/A | University campus |

1 session/week |

60–75 minutes |

1 year | No |

| Italy (2) | 2000– 2009 |

Obs-2 | Yogic breathing-2 |

N/A-1 Laboratory- 1 |

1 session-2 | N/A-1 30 minutes- 1 |

Once-2 | No-2 |

|

Jamaica (2) |

2008– 2011 |

RCT- 1 Obs-1 |

Hatha-1 Yogic meditation- 1 |

N/A-1 University campus-1 |

1 session/week -2 |

N/A-1 2 hours- 1 |

6 weeks-1 24 weeks-1 |

Yes-2 |

| Japan (7) | 1993– 2009 |

Obs-7 | N/A-1 Hatha-4 Yogic breathing-1 Yogic mindfulness -1 |

Home-1 Laboratory- 5 University 1 |

1 session-4 1 session/day-2 3 sessions/wee k-1 |

N/A-1 10–60 minutes- 1 15 minutes- 1 30–60 minutes- 1 45 minutes- 2 60 minutes- 1 |

Once-4 2 days-1 1 week-1 2 weeks-1 |

Yes-1 No-6 |

| Korea (1) | 2011 | RCT- 1 |

N/A | N/A | 3 sessions/wee k |

60 minutes |

16 weeks | No |

| Mexico (1) | 2009 | Obs-1 | Hatha | Medical center |

5 sessions/wee k |

90 minutes |

11 weeks | No |

| Nepal (5) | 2005– 2008 |

Obs-5 | N/A-2 Yogic breathing-2 Hatha-1 |

N/A-1 Laboratory- 3 Residential yoga center- 1 |

N/A-1 1 session-1 1 session/day-3 |

N/A-1 5 minutes- 1 15 minutes- 1 30–40 minutes- 1 60 minutes- 1 |

Once-1 2 weeks-1 4 weeks-1 40 days-1 12 weeks-1 |

Yes-2 No-3 |

|

Netherlan ds (3) |

1994– 2012 |

RCT- 2 Obs-1 |

N/A-2 Yogic breathing-1 |

Laboratory- 1 Workplace- 2 |

1 session-1 1 session/week -2 |

10 minutes- 1 45 minutes- 2 |

Once-1 6 months-2 |

No-3 |

| Russia (2) | 2002– 2004 |

Obs-2 | Hatha-1 Sahaja-1 |

Laboratory- 2 |

N/A-1 1 session-1 |

N/A-1 5 minutee s-1 |

Once-2 | No-2 |

|

Slovenia (3) |

2010– 2011 |

RCT- 3 |

Hatha-1 Yoga in Daily Life-2 |

Hospital clinic-2 Rehabilitati on center-1 |

1 session/day-2 1 session/week -1 |

N/A-1 60 minutes- 2 |

1 week-2 10 weeks-1 |

No-3 |

|

Sri Lanka (1) |

2010 | RCT- 1 |

Hatha | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No |

| Sweden (5) | 1983– 2010 |

Obs-5 | N/A-1 SKY-1 Kundalini-2 Yogic breathing-1 |

Hospital clinic-1 Laboratory- 2 Workplace- 1 Yoga studio-1 |

1 session-2 1 session/week -1 2 sessions/wee k-1 6 sessions/wee k |

N/A-1 2 minutes- 1 10 minutes- 1 60 minutes- 1 2 hours- 1 |

N/A-1 Once-2 6 weeks-1 16 weeks-1 |

Yes-2 No-3 |

| Taiwan (6) | 2008– 2011 |

RCT- 1 Obs-5 |

Prenatal yoga-1 Silver yoga- 5 |

Assistive living center-1 Home-1 Nursing home-1 Senior center-3 |

3 sessions/wee k -6 |

55–75 minutes- 1 60 minutes- 1 70 minutes- 4 |

4 weeks-1 12 weeks-1 12–14 weeks-1 24 weeks-3 |

Yes-1 No-5 |

|

Thailand (3) |

2003– 2008 |

RCT- 2 Obs-1 |

N/A-1 Hatha-1 Nidra-1 |

N/A-2 Yoga center-1 |

1 session/week -1 3 sessions/wee k-1 5 sessions/wee k-1 |

60 minutes- 2 63 minutes- 1 |

8 weeks-1 10 weeks-1 16 weeks-1 |

Yes-2 No-1 |

| Turkey (4) | 2007– 2010 |

Obs-3 | Hatha-3 | N/A-1 Hospital clinic-1 Laboratory- 1 |

N/A-1 2 sessions/wee k-2 |

60 minutes- 3 |

8 weeks-2 12 weeks-1 |

No-3 |

|

United Arab Emirates (1) |

2008 | Obs-1 | Vishwas- Raj yoga |

Home | 12 sessions | N/A | 8 weeks | Yes |

|

United Kingdom (14) |

1975– 2012 |

RCT- 10 Obs-4 |

N/A-1 Iyengar-5 Hatha-3 Yogic meditation- 3 Dru-1 Yogic breathing-1 |

N/A-5 Hospital clinic-1 Laboratory- 2 Open park-1 University campus-3 Nonmedical health facility-2 |

N/A-1 2 sessions/day- 1 1 session/week -5 1–3 sessions/wee k-1 2 sessions/wee k-5 3 sessions/wee k-1 |

N/A-1 15 minutes- 1 30 minutes- 1 60 minutes- 4 75 minutes- 4 90 minutes- 3 |

N/A-1 2 weeks-1 6 weeks-4 8 weeks-1 10 weeks-1 12 weeks-6 |

Yes-7 No-7 |

Note: The last search date for the systematic review was April 27, 2012.

Case, case study; N/A, not available; Obs, observational study; SKY, Sudarshan Kriya Yoga

Results

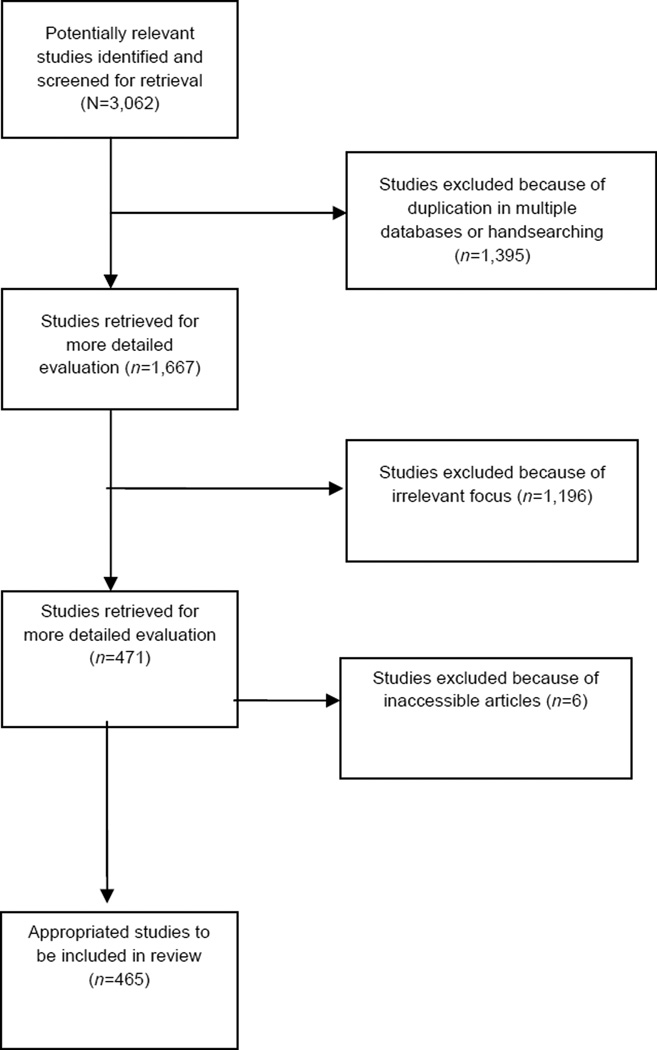

Following PRISMA guidelines, Figure 1 provides a flow chart of the search and selection process. Table 1 presents information on the number of articles that were identified, excluded, and included by database and journal searched. The initial search of electronic databases and handsearching of five key journals resulted in a sample of 3,062 articles. Of these, 1,395 were present in more than one database or journal, and these duplicates were excluded from further review. Of the remaining 1,667 articles for review, 1,196 articles did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded, and six articles were not obtainable from two university libraries or through attempts to contact the first author, leaving 465 articles for inclusion in the systematic review (Figure 1). Handsearching the five key journals’ tables of contents yielded one additional article for review (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of yoga interventions for systematic review

Table 1.

Literature search results by database and journal

| Database or Journal |

Initial results |

Duplicate studies; excluded |

Did not meet inclusion criteria; excluded |

Unable to retrieve full article; excluded |

Included in review |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PubMed | 1,871 | 735 | 768 | 6 | 363 |

| PsycINFO | 229 | 143 | 41 | 45 | |

| Ovid (database of Alternative and Complementary Medicine) | 483 | 47 | 382 | 54 | |

| AgeLine | 8 | 0 | 5 | 3 | |

| Arch Intern Med | 31 | 31 | 0 | 0 | |

| BMC Complement Altern Med | 52 | 52 | 0 | 0 | |

| Evid Based Complement Alternat Med | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0 | |

| Int J Yoga | 40 | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| J Altern Complement Med | 323 | 322 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | 3,062 | 1,395 | 1,196 | 471 | 465 |

Table 2 provides information on the geographic location of the included studies, publication years, study designs, styles of yoga involved in the interventions, descriptions of the intervention setting, frequency and duration of the yoga sessions, duration of the intervention, and whether or not home practice was part of the intervention. Findings on the various outcomes measured in these studies are described below. India and the U.S. are listed first in Table 2, because they represent the largest number of yoga intervention studies. Thereafter, the countries are listed in alphabetical order. Intervention information is summarized in the text below. Appendix 3 contains definitions of the many yoga styles and information on which of the eight limbs was perceived as present in the specific yoga interventions included in this review.

Geographic Location

Thirty countries were represented in these 465 articles, with India (n=228) and the U.S. (n=124) reporting the most yoga interventions (Table 2). Other countries included the United Kingdom (n=14), Canada (n=12), Australia, Brazil, Germany (n=8 each), Japan (n=7), Taiwan (n=6), Nepal, Sweden, and the Czech Republic (n=5 each), Iran and Turkey (n=4 each), the Netherlands, Slovenia and Thailand (n=3 each), and Denmark, Indonesia, Italy, Jamaica, and Russia (n=2 each). Belgium, Ethiopia, France, Israel, Korea, Mexico, Sri Lanka, and the United Arab Emirates were the geographic locations of one intervention each.

Yoga Intervention Location

The setting in which the yoga intervention took place varied from those such as a residential yoga center (n=65, 15%), laboratory setting (n=90, 20%), health facility, clinic, or ward (n=61, 13%), yoga studio or clinic (n=44, 10%), or university campus (n=35, 8%). In 103 (23%) yoga interventions, the setting of the intervention was not described.

Styles of Yoga

Unsurprisingly, a large number of yoga styles were involved in these 465 yoga interventions. The most common yoga styles are mentioned below; a full listing of all yoga styles can be found in Table 2 and Appendix 2. Hatha yoga was part of 129 (28%) interventions, followed by Iyengar yoga in 41 (9%) interventions, and yoga that involved primarily breathing such as “yogic breathing” interventions (n=37, 8%), Sudarshan Kriya Yoga (SKY; n=24, 5%), Kapalbathi (n=8, 2%), and Kundalini (n=7, 2%). Sixty-five (15%) studies did not describe the style of yoga used in the intervention. Asanas were mentioned as yoga components in 369 (81%) interventions, but were either minimally or not at all described in 200 (54%) of these (Appendix 2). Only 56 (12%) studies mentioned the amount of time devoted to each aspect of yoga during the intervention (Appendix 2).

Frequency and Duration of Sessions and Length of Interventions

Most interventions described the frequency of the yoga sessions (i.e., how often the yoga sessions took place during the intervention; n=342, 75%) and the duration of the yoga session (i.e., how long the yoga sessions lasted each time they occurred; n=379, 83%). Frequencies spanned from only one session for the entire intervention (n=64, 14%) to six sessions per week of the intervention (n=16, 4%). Most yoga session durations were either 60 minutes (n=108, 24%), 75 minutes (n=23, 5%), or 90 minutes (n=57, 13%) long. Some laboratory sessions were ≤5 minutes (n=14, 3%). Length of the yoga intervention was described in almost all studies (n=438, 96%), spanning from one session to 2 years.f

Inclusion of Home Practice in the Intervention

Most interventions (72%, n=336) did not report a home practice aspect of the yoga intervention. In many of the interventions that did provide a home practice component, adherence to the home practice was not described.

Yoga Intervention Study Designs

Most yoga intervention studies consisted of prospective, observational study designs (n =298, 64%), with or without a comparison group. An RCT (n=151) was the study design used in 32% of the yoga interventions in this systematic review. Six (1%) interventions had a case study design.

Outcomes Assessed in Yoga Interventions

A wide range of outcomes were assessed across the 465 interventions, and many interventions reported assessing multiple outcomes. Of these outcomes, 186 (40%) were classified as physiologic outcomes, such as heart rate, blood pressure, or hormonal levels; one hundred twenty-three (26%) outcomes were classified by two authors as physical functioning outcomes, such as chronic pain and arthritis; one hundred fourteen (25%) were mental and emotional health outcomes, including depression, anxiety, and stress; thirty-nine (8%) interventions assessed cognitive and perceptual outcomes, such as concentration, attention, and memory; thirty (6%) outcomes assessed general well-being, such as quality of life or mindfulness; and 12 (3%) interventions examined workplace outcomes, including employee satisfaction and fatigue. Interventions often assessed more than one outcome.

Additional Emphases of Yoga Interventions

Because 369 (81%) of the studies reported including asanas in the yoga intervention, information on additional emphases from the yoga interventions was also collected from these studies. Table 4 includes details on the 16 different emphases other than asanas mentioned in the 465 studies. Breathing practice (pranayama), one of the eight limbs, was the most common additional emphasis, described in 196 (42%) interventions. This was followed by an additional emphasis on meditation (dharana and dhyana), described in 108 (23%) interventions, and relaxation exercises described in 68 (15%) interventions. In 173 (37%) interventions, no additional emphases of the yoga intervention were described.

Table 4.

Emphases other than asanas in yoga interventions, n=465

| Type of emphasis | n(%) |

|---|---|

| Not provided | 173 (37) |

| Biofeedback | 2 (0.4) |

| Breathing (exercises, practices) | 196 (42) |

| Centering | 3 (0.6) |

| Chanting | 9 (1.9) |

| Cleansing practices | 12 (2.5) |

| Compassion towards self (e.g., non-violence) | 2 (0.4) |

| Counseling or psychotherapy | 3 (0.6) |

| Devotional sessions/song or prayer | 20 (4.3) |

| Diet | 12 (2.5) |

| Education about yoga, discussion, or lectures | 46 (9.9) |

| Imagery or visualization | 14 (3) |

| Meditation | 108 (23) |

| Mindfulness or awareness | 26 (5.6) |

| Stress management | 8 (1.7) |

| Stretching exercises | 7 (1.5) |

| Relaxation exercises | 68 (15) |

Yoga Instructor Experience

In 277 (60%) studies, the authors did not provide any information on the yoga instructor leading the studies’ interventions (Table 5). In 53 (11%) studies, the authors described the yoga instructor as “certified in yoga,” but did not include any information on where that certification was obtained. In 39 (8%) studies, the yoga instructor was described as “trained” in yoga, again without additional information, and in 27 (6%) of studies, the instructor was described as “experienced” or an “expert” in yoga. In eight (1%) studies, the authors identified the instructor as someone who was a Registered Yoga Teacher (RYT), a qualification provided in the U.S. for yoga teachers who have reached a specific number of hours of training, usually 200, 300, or 500. In seven (1%) studies that took place outside of the U.S., the authors described the number of years the instructor had taught yoga, or the number of hours of training in which the instructor had engaged.

Table 5.

Details provided on intervention yoga instructor’s level of training, n=465

| Instructor’s level of training | n(%) |

|---|---|

| Not provided | 277 (60) |

| Registered Yoga Teacher | 8 (1.7) |

| Certified in yoga | 53 (11) |

| Trained in yoga | 39 (8.4) |

| Licensed to practice yoga | 4 (0.9) |

| “Experienced” or “expert” | 27 (5.8) |

| Nurse as yoga instructor | 4 (0.9) |

| Psychologist as yoga instructor | 5 (1) |

| Physician as yoga instructor | 5 (1) |

| Physical therapist as yoga instructor | 4 (0.9) |

| Author as yoga instructor | 15 (3.2) |

| Audiotape-guided instruction (no instructor present) | 5 (1) |

| More than 1 instructor involved in yoga teaching | 14 (3) |

| Number of years of training/number of hours of training provided | 7 (1.5) |

RCTs: Quality Assessment and Descriptions

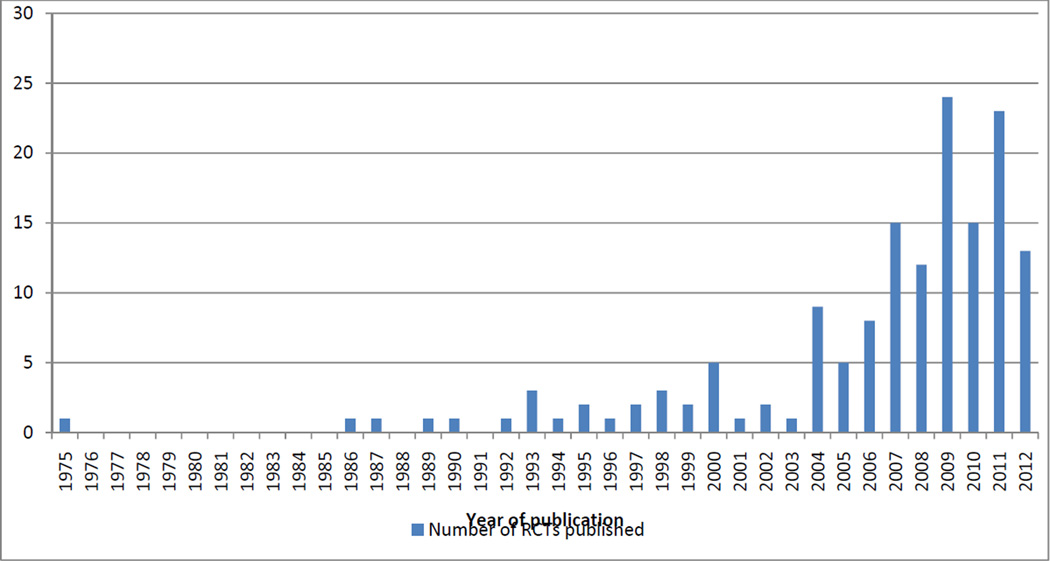

A total of 151 RCTs were assessed by two authors for methodologic quality using the seven checklist categories (Table 3).13 Overall methodologic quality was generally low, with only baseline characteristics of the intervention sample being examined to ensure similarity of groups (n=97, 64%) more often than not (n=19, 13%) or not mentioned at all (n=35, 23%). In the other six categories of methodologic quality, studies often did not adequately address a methodologic concern or did not provide any information in the description of the study to assess this at all. Figure 2 provides information on the spread of RCT methodology in the yoga literature over time, with only one RCT published in 1975 in the United Kingdom, no RCTs published between 1976 and 1985, between zero and three RCTs per year published between 1986 and 1999, in the U.S., United Kingdom, India, Germany, and Japan, and a marked increase in RCT methodology beginning in 2000, when five RCTs were published.

Table 3.

Quality assessment of yoga intervention RCTs, n=151

| Rating | Random group allocation |

Group allocation concealed |

Baseline similarity of groups examined |

Assessors blinded to group |

Unexpected imbalances in dropouts assessed |

Authors measured what they said they would |

Missing data methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate description | 52 (34%) | 37 (24%) | 97 (64%) | 38 (25%) | 21(14%) | 88 (58%) | 26 (17%) |

| Not adequate description | 9 (6%) | 13 (9%) | 19 (13%) | 15 (10%) | 71(47%) | 63 (42%) | 76 (50%) |

| Information not available | 90 (60%) | 101(67%) | 35 (23%) | 98 (65%) | 59 (39%) | 0 (0%) | 49 (33%) |

Figure 2.

Number of RCTs published from 1975 through April 27, 2012

Iyengar yoga (n=26, 17%) was the most common form of yoga in these published RCTs. A majority (n=96, 64%) of these intervention sessions lasted longer than 60 minutes in duration, with a range of 15 minutes to 17 hours, considerably longer than the aforementioned non-RCT interventions. Intervention length varied from a one-time session (n=5, 3%) to more than 8 weeks (n=100, 66%). Hospital clinics or healthcare facilities were the most common location of the yoga interventions (n=39, 26%), with other locations including yoga studios or yoga centers (n=24, 16%) and university campuses (n=13, 9%). RCT studies described having a home practice component 45% (n=68) of the time.

Discussion

Summary of Evidence

This review addressed the following three research questions: (1) What are the characteristics of yoga interventions in the literature? (2) What is the methodologic quality of the subset of interventions that are RCTs? and (3) How well are yoga interventions reported in the literature, according to elements of practice, duration, frequency, location, environment, additional yoga intervention emphases, and teacher experience? Overall, these results demonstrate that reporting of yoga intervention components varies widely in the published literature, and that, in the aggregate, the methodologic quality of these interventions is low.

Yoga intervention studies have been conducted primarily in India and the U.S., although a handful of studies have been conducted in countries representing all populated continents. This likely reflects the origin of the practice in India as well as the well–developed health research infrastructure in the U.S. European countries are well represented in the identified yoga studies. However, the dates of recent yoga studies in many different countries suggest that both the interest in yoga and yoga research is increasing in many areas of the world.

Nearly one fourth of yoga intervention studies failed to report the site where the intervention was provided. The facility may be important, again, based on cultural factors that vary tremendously and may affect expectations.

The variety of health or well-being outcomes targeted by yoga interventions is impressive. Various conditions have been treated, including cancer, chronic low back pain, and psychiatric illnesses such as depression and anxiety. However, the largest number of interventions has targeted physiologic responses such as heart rate, metabolic and hormonal changes, and respiratory rates. These outcomes were mostly assessed in observational laboratory studies, where the yoga sessions were short in frequency and duration, without real-world applications. For yoga to become a recognized health intervention for treating health globally, yoga interventions need to move from the laboratory to community-based settings, to reach a wider range of people and to assess physical and mental health functioning.

Despite the large number of outcomes reported for yoga interventions, the content of these interventions were not well described in most of the studies. Although asana was a component of 81% of the studies, 51% of these studies provided a minimal description or no description of all of the asanas. Given the centrality of asana to yoga interventions, such lack of description is a major limitation in interpreting results. If asana is proposed to be a major component of the effects of an intervention, it is essential to know the asanas participants are doing as part of the intervention, how often, and for how long. Nearly two thirds of the studies did describe additional emphases other than asanas in the yoga interventions, with breathing practices, meditation, and relaxation exercises being the most common additional emphases, representing different limbs of yoga. What makes the practice of yoga unique is that practitioners can flow seamlessly through the different limbs of yoga in one session; however, documenting these many different components of yoga is not yet widespread, as 37% of the interventions did not report on additional emphases in the yoga intervention.

Sherman10 rightly points out that the selection of the instructor is a valuable part of any yoga intervention. In this review, 60% of yoga interventions did not describe any qualifications of the yoga instructor conducting the interventions, and most of the studies that included information provided vague qualifications, describing instructors as trained, certified, or experienced. Given the role instructors play in facilitating the right atmosphere for yoga interventions, the trust in which yoga students place on their instructor’s knowledge, and the motivation that instructors provide to students to complete the yoga session, it is important that future intervention research not only place great care in selecting appropriately trained instructors, but also report this information. Yoga instructor training may be a mediating variable, distinguishing between successful and unsuccessful yoga interventions. Until these data are reported consistently, it is not possible to understand the impact of the instructor fully.

With increased attention to the quality of methods used, yoga research may be entering a more mature phase. This review highlights the lack of description and rigor of extant studies. Without adequate information, it is impossible to determine whether discrepancies in findings among studies is due to methodologic aspects such as the type or length of different components like asana or meditation or the length or intensity of the sessions. Given the interest expressed by increasing numbers of people in yoga as a health modality,1 as well as its potential for healing and health promotion, the need to determine whether and how yoga affects various aspects of health and well-being is great. Future research should not only use appropriately rigorous standards of methodology, but also provide the requisite details to permit aggregation of research findings and enhanced clarity regarding the effectiveness of yoga in improving health and well-being.

Limitations

Although this review included studies representing 30 countries, it is limited by its inability to include studies published in languages other than English. The review was as inclusive as possible of all yoga interventions, using only the text word yoga in its search strategy, but it is possible that some yoga interventions were not included in this review. Although 40% of the included yoga interventions from India were published in Indian journals, researchers should consider using other publication databases such as IndMED in future reviews. Another limitation is that the review provided only a scoping review of the literature and did not report on the effectiveness of any of the outcomes targeted by the yoga interventions. It would have been a difficult task to assess outcomes quantitatively, given the heterogeneity of the studies and the lack of rigorous interventions.17 Once higher–quality yoga intervention studies are undertaken and reported, comparative effectiveness and meta-analyses will be more appropriate for assessing yoga intervention outcomes.

Conclusions

This review of the large body of yoga research provides a summary description and highlights both the strengths and weaknesses of much of the formal yoga research that has been published in the medical and psychological literature. Future yoga researchers should endeavor to include the components of yoga identified in this review, paying careful attention to the duration, frequency, dose, location of yoga, additional emphases of yoga, instructor training, home practice description, and the potential sources of bias that can result in low–quality yoga intervention studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine/NIH to Principal Investigator Crystal L. Park, PhD (1R01AT006466-01). Dr. Elwy is also an investigator with the Implementation Research Institute at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis, through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (R25 MH080916-01A2) and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

References

- 1.Saper RB, Eisenberg D, Davis R, Culpepper L, Philips R. Prevalence and patterns of adult yoga use in the U.S.: results of a national survey. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004;10(2):44–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birdee GS, Legedza AT, Saper RB, Bertisch SM, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Characteristics of yoga users: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1653–1658. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0735-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryant EF. The yoga sutras of Patanjali: a new edition, translation and commentary. New York: North Point Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, Miglioretti DL, Deyo RA. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(12):849–856. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-12-200512200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Wellman RD, et al. A randomized trial comparing yoga, stretching, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(22):2019–2026. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross A, Thomas S. The health benefits of yoga and exercise: a review of comparison studies. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(1):3–12. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang K. A review of yoga programs for four leading risk factors of chronic diseases. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4(4):487–491. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel NK, Newstead AH, Ferrer RL. The effects of yoga on physical functioning and health related quality of life in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(10):902–917. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park CL. Mind-body CAM interventions: current status and considerations for integration into clinical health psychology. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69(1):45–63. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman KJ. Guidelines for developing yoga interventions for randomized trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:143271. doi: 10.1155/2012/143271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groessl EJ, Weingart KR, Aschbacher K, Pada L, Baxi S. Yoga for veterans with chronic low-back pain. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14(9):1123–1129. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG the PRISMA group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. 3rd ed. York: University of York; 2009. www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/Systematic_Reviews.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to the clinical preventive services: report of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, “levels of evidence.”. Darby PA: DIANE Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elwy AR, Hart GJ, Hawkes SJ, Petticrew M. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections and human immunodeficiency virus in heterosexual men: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(16):1818–1830. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.16.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCall MC, Ward A, Roberts NW, Heneghan C. Overview of systematic reviews: yoga as a therapeutic intervention for adults with acute and chronic health conditions. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:945895. doi: 10.1155/2013/945895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.