Abstract

Amphidiploid species in the Brassicaceae family, such as Brassica napus, are more tolerant to environmental stress than their diploid ancestors.A relatively salt tolerant B. napus line, N119, identified in our previous study, was used. N119 maintained lower Na+ content, and Na+/K+ and Na+/Ca2+ ratios in the leaves than a susceptible line. The transcriptome profiles of both the leaves and the roots 1 h and 12 h after stress were investigated. De novo assembly of individual transcriptome followed by sequence clustering yielded 161,537 nonredundant sequences. A total of 14,719 transcripts were differentially expressed in either organs at either time points. GO and KO enrichment analyses indicated that the same 49 GO terms and seven KO terms were, respectively, overrepresented in upregulated transcripts in both organs at 1 h after stress. Certain overrepresented GO term of genes upregulated at 1 h after stress in the leaves became overrepresented in genes downregulated at 12 h. A total of 582 transcription factors and 438 transporter genes were differentially regulated in both organs in response to salt shock. The transcriptome depicting gene network in the leaves and the roots regulated by salt shock provides valuable information on salt resistance genes for future application to crop improvement.

1. Introduction

Soil salinity is widespread throughout the globe, with more than 20 million hectares of world's land being estimated to be salt-affected [1–3]. It has been reported that 45 million ha of the current 230 million ha of irrigated land and 32 million ha of the 1,500 million ha under dryland agriculture are salt-affected [3]. Salinity occurs through natural or human-induced processes that result in the accumulation of dissolved salts. Particularly, salinity resulting from natural disasters such as tsunamis often has an immediate impact on agricultural land due to a sudden substantial increase in soil salinity level. The Great East Japan Earthquake, which occurred in 2011, inundated more than 20,000 ha of agricultural land, resulting in substantial reduction of crop production [4].

Salt tolerance is a very complex phenomenon in most plant species since it involves various mechanisms at cellular, tissue, organ, or whole plant levels. Stress exposure at different development stages affects different pathways for adaptation and homeostasis resulting in different gene expression profiles. Over the past several decades, germplasms of the Brassicaceae oilseed crops have been screened for salt tolerance, and some elite lines have been identified [5–7]. Based on various studies of salt tolerance in Brassica species, the amphidiploid species in the triangle of U [8], that is, Brassica carinata, Brassica juncea, and Brassica napus, outshone the diploid species, that is, Brassica rapa, Brassica nigra, and Brassica oleracea [9–11]. Comparative salt tolerance study of Brassica species has also revealed that B. napus is more salt tolerant than the other amphidiploids, that is, B. carinata and B. juncea [12].

Gene expression response varies with time from stress exposure. Recent transcriptomic research on plant salt tolerance has been gradually shifting from salt-sensitive glycophytes to salt tolerant halophytes. The halophyte species which has been extensively surveyed for the transcriptomic response to salt is salt cress (Thellungiella halophila) [13, 14]. Recently, the salt-responsive transcriptome of a semimangrove plant (Millettia pinnata), which is a glycophyte with moderate salt tolerance, has also been thoroughly characterized and study has revealed various affected pathways [15]. Although transcriptome analysis in salinity response has been extensively conducted in these two species, the salt-responsive transcriptomic regulation of salt tolerant polyploid species is still worth unveiling since their transcriptome architecture is more complex than that of diploid species and they can generally withstand adverse environmental conditions better than their diploid ancestors.

The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has progressively revolutionized genomic studies. RNA-seq technologies have been employed for studying both model and nonmodel organisms. For model organisms, in which both genome sequences and gene annotations are available, a protocol for differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments described by Trapnell et al. is suitable for conducting the transcriptome analysis [16]. For nonmodel organisms, deep sequencing followed by de novo assembly and clustering is necessary to generate reference transcriptome. Alternatively, genome sequences and expressed sequence tag (EST) sequences of related species can be utilized as references for mapping. Hybridization-based microarray technologies have been the dominant approaches for the study of gene expression in the past decade. However, these methods suffer from several limitations including reliance upon existing information about the available genome sequence, high background levels attributed to cross-hybridization, and a limited dynamic range of detection owing to both background and saturation of signals [17, 18]. Conversely, RNA-seq offers several advantages and is much superior to the microarray technologies because of a wider range of expression levels, less noise, higher throughput, more information to detect allele-specific expression, novel promoters, splice variants and isoforms, and no necessity of prior knowledge of both genome and gene sequences [19, 20].

Numerous studies have been performed to discover genes that contribute to salinity tolerance in B. napus [21–25]. However, only a limited number of genes have been evaluated and these are not sufficient to characterize the overrepresented molecular mechanism underlying moderate salt tolerance. In this study, we commenced a comprehensive transcriptome analysis of a B. napus line, which is one of the most salt tolerant lines obtained in our prior screening [7]. In Japan, a sudden increase in soil salinity due to tsunami has been the major problem in agriculture sector [4]. To grow oilseed rape or other brassica species, farmers would either directly sow seeds into soil or transplant germinated seedlings into soil. Plants experience sudden increase in salinity after transplantation into salt contaminated land and this condition is more akin to salt shock that has been described by Shavrukov [26]. Taji et al. also suggested that rapidly inducible genes should be important for salt tolerance [14]. Therefore, this study focused on the initial transcriptome regulation in leaves and roots of this line in response to sudden increase in salinity. Transcriptomic changes in this line were evaluated by comparing the leaf and root expression profiles at 1 h and 12 h time points of salt challenge.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

Seeds of the B. napus line N119 maintained in the Tohoku University Brassica Seed Bank were surface-sterilized with 70% ethanol and 1% sodium hydrochlorite and germinated on MS medium. Germinated seedlings were grown in plastic pots (diameter = 10.5 cm, height = 9 cm) containing vermiculite under a 16/8 h photoperiods at 23°C. Plants were watered twice a week with 1/2000 HYPONeX fertilizer solution (Hyponex, Osaka, Japan) at a final concentration of 30 μg/L nitrogen, 20 μg/L phosphorus, and 25 μg/L potassium. Salt treatment was implemented when the seedlings were 3 weeks old. The volume of each plant pot was approximately 800 mL. For salt treatment, plants were watered by 200 mM of NaCl solution. The treatments were initiated at 8.00 a.m. and each individual plant was watered with 300 mL of salt water to field capacity. Meanwhile, a group of control plants were watered with an equal volume of distilled water.

2.2. Analysis of Ion Contents

For the quantitative analysis of ions, that is, Na+, K+, and Ca2+, the aerial parts of the seedlings were dried at 85°C for 10 days. Dried samples were ground into powder using tissue lyzer, MiXer MiLL MM300 (QIAGEN Inc., USA), and 20 mg of the powder was digested with 5 mL of 1 M hydrochloric acid overnight and filtered using Whatman 42 mm paper. Ion contents were estimated using an A-2000 atomic absorption spectrophotometer (Hitachi High-Technologies, Japan). Standard solutions of Na+, K+, and Ca2+ were used for calibration.

2.3. Sample Collection, RNA Preparation, and Sequencing

The roots and leaves were sampled at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h after stress with three replicates for each time point. Both the whole root and the third leaf were sampled simultaneously from each individual plant and were separately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C prior to RNA isolation. The total RNA was extracted using SV Total RNA Isolation System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The quality of the RNA was determined by NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, USA) and a 2100 Bioanalyzer RNA Nanochip (Agilent Technologies GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The expression of salt-responsive genes was analyzed for each sample in order to determine the suitable time point for samples to be sent for sequencing (Additional file 1 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/467395). The total RNA samples of three replicates for each organ and each time point were bulked. At least 20 μg of total RNA samples of both the root and leaf tissues (both salt treated and control) collected at 1 h and 12 h after stress was sent to the Beijing Genomics Institute, Hong Kong, for commercial Illumina sequencing.

mRNAs were purified using oligo(dT)-attached beads and fragmented into small pieces (100–400 bp). The cleaved RNA fragments were then primed with random hexamers and subjected to the synthesis of the first-strand and second-strand cDNAs. The synthesized cDNAs were ligated with paired-end adaptors. The cDNA fragments with 200 bp (+20 bp) size were then selected by agarose gel electrophoresis and enriched by PCR amplification. Finally, eight cDNA libraries were constructed for sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq2000 sequencer. Reads for all eight transcriptomes of B. napus are available through the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA), study accessions (GenBank: SRP028575).

2.4. De Novo Assembly and Sequence Clustering

The raw reads were cleaned by trimming adapter sequences, low-quality sequences (reads with ambiguous bases “N”), and reads with more than 10% Q < 20 bases. De novo assembly of the clean reads was performed using Trinity [27] with default setting with an optimized k-mer length of 25 and the scaffolds obtained were denoted as unigenes. The Trinity unigenes of eight libraries were then further clustered into a comprehensive transcriptome using CD-HIT-EST software with a sequence identity cut-off of 0.9 and comparison of both strands [28]. For comparison, SOAPdenovo (version 1.04; http://soap.genomics.org.cn/soapdenovo.html) [29] was also used to conduct de novo assembly with default setting except for the k-mer value, which was set at specific values of 29, 31, 33, 35, 37, 39, 41, 43, 45, 47, 49, 51, 53, 55, 57, 59, 61, and 63. SOAPdenovo assembly with k-mer of 51 produced the highest N50 value and average scaffold length. Therefore, SOAPdenovo unigenes produced by k-mer of 51 were used for further clustering analysis by CD-HIT-EST.

Both all-unigenes of Trinity and SOAPdenovo were searched against NCBI Brassica napus nonredundant unigene sequences with an E value cut-off of 1.0 × 10−5. The Trinity all-unigenes corresponded to 61,015 Brassica napus unigene sequences, while the SOAPdenovo all-unigenes got fewer hits, that is, 58,357 sequences. Therefore, Trinity all-unigenes were used for subsequent analysis.

2.5. Expression Analysis and Identification of DEGs

Clean reads of eight transcriptomes were mapped back to all-unigenes with RSEM v1.2.3 [30] allowing the maximum 3 mismatches. The reads per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads (RPKM) values were applied to measure the gene expression levels. For a given all-unigene, eight RPKM values were generated from eight transcriptomes, respectively. DEGs between control and salt-water treated samples were identified by EBSeq R package v1.1.5 [31]. Since biological replicates were pooled, transcript specific variance was determined by estimating the across-condition variance as recommended in the vignette [32]. Salt-responsive genes were identified with a FDR<0.01 and a normalized fold change ≥2.

2.6. Functional Categorization and Annotation

To assign gene ontology annotation for all-unigenes, the all-unigenes were aligned to SwissProt database using BLASTX with an E value cut-off of 1.0 × 10−5. The results with the best hits were extracted. The all-unigenes without SwissProt hits were searched against the NCBI NR protein database by BLASTX with an E value cut-off of 1.0 × 10−5. The GO annotations for the top blast hits were retrieved with the Blast2GO program [33, 34], followed by functional classification using WEGO software [35]. In addition, KEGG ontology was assigned to each of the all-unigenes by KOBAS 2.0 (KEGG Orthology-Based Annotation System, v2.0), in which all-unigenes were aligned to the KO database by BLASTX with an E value cut-off of 1.0 × 10−5 to retrieve gene IDs, followed by ID mapping to KO terms [36]. Furthermore, all-unigenes were searched against Plant Transcription Factor Database v2.0 (PlantTFDB 2.0) [37] and the Transporter Classification Database (TCDB) [38, 39] with an E value cut-off of 1.0 × 10−5 and more than 80% query coverage.

The GO enrichment analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis were analyzed by BiNGO plugins for Cytoscape, using the hypergeometric test for statistical analysis with the whole B. napus transcriptome as the background [40]. For P value correction, the rigorous Bonferroni correction method was employed. The cut-off P value after correction was 0.05.

2.7. RT-PCR and Real-Time Quantitative PCR

The gene-specific primers for real-time PCR analysis were designed using Primer 3 by applying the parameters described by Thornton and Basu [41]. We conducted RT-PCR for 40 DEGs using B. napus actin gene as control (Additional file 1). The first-strand cDNAs were synthesised from 1 μg of total RNAs using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Ten microliters of PCR samples containing 1 μL of first-strand cDNAs and 5 pmol of primers were then subjected to 30 cycles of 30 s denaturing at 94°C, 30 s annealing at 60°C, and 30 s extending at 72°C. The PCR products were electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gel.

Real-time PCR was performed on CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using 1 μL of cDNAs and SsoAdvanced SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). The thermal conditions were set at 95°C for 3 min denaturation, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 1 s and 60°C for 30 s. Following denaturation at 95°C for 30 s and cooling to 65°C for 30 s, a melting curve was generated by heating from 65°C to 95°C in 0.5°C increments with a dwell time at each temperature of 2 s while continuously monitoring the fluorescence. All of the reactions were performed in triplicate and the average expression value was calculated. The relative expression level for each gene was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method with normalization to the internal control gene [42].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Ion Contents in a Salt Tolerant Line and a Salt Susceptible Line

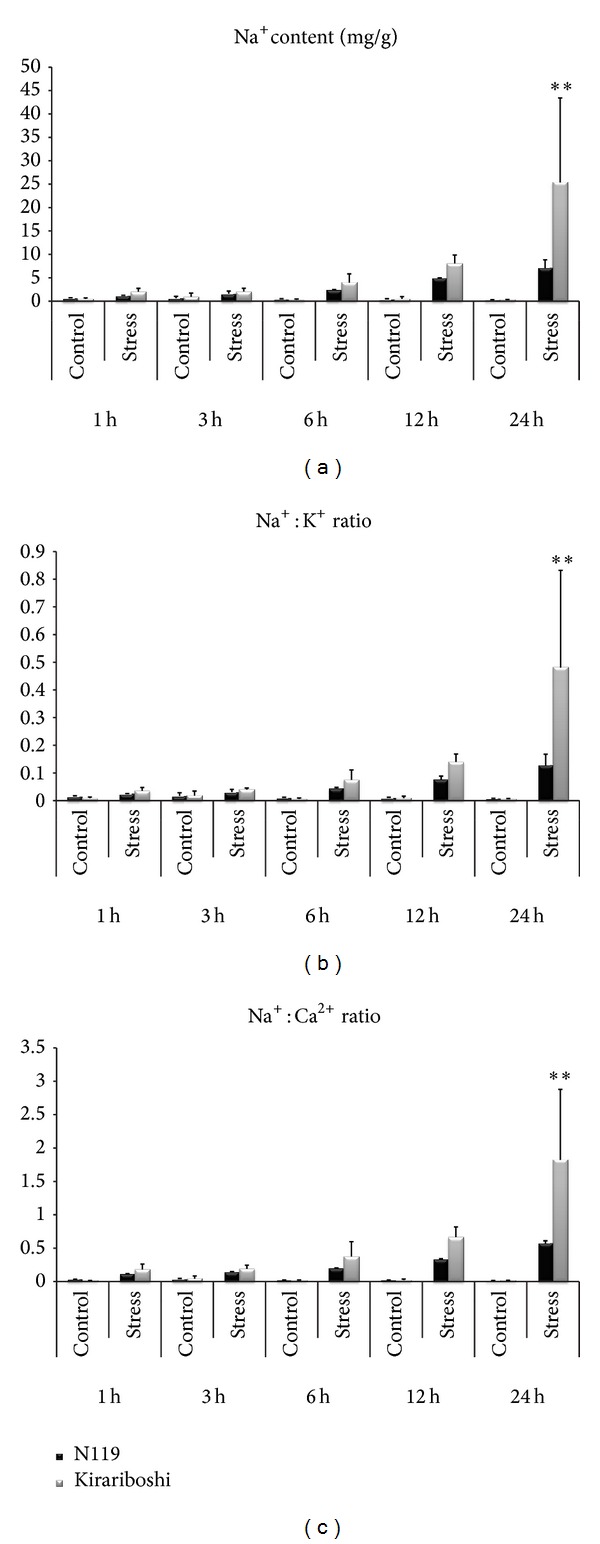

Transcriptome of a salt tolerant line, N119 of cv. “Sapporo,” which has been evaluated as being one of the most salt tolerant lines in our previous study [7], was investigated. Based on our previous study [7], salt tolerance for various B. napus lines has been screened by irrigating 3-week-old seedlings with 200 mM NaCl and the degree of salt tolerance has been determined by the ratio of dry weights of plants grown with NaCl to those of plants grown without NaCl. N119 has been identified as tolerant line due to its high dry weight ratio [7]. To further confirm the salt tolerance of N119, seedlings of N119 together with a susceptible line, “Kirariboshi,” for comparison were subject to short-term salt stress, and their responses were analyzed by measuring Na+, K+, and Ca2+ contents. Instead of alleviation of biomass reduction, the maintenance of a low Na+ content and a low Na+/K+ ratio has been widely used as an index of salt tolerance [43]. An increase of the period of exposure to salinity resulted in an increase in the Na+ content, the ratio of Na+/K+, and the ratio of Na+/Ca2+ in both lines (Figure 1). However, N119 seedlings performed different from those of “Kirariboshi.” The Na+/K+ ratio and Na+/Ca2+ ratio of “Kirariboshi” reached ~2-fold that of N119 12 h after salt treatment and significant differences were observed at 24 h after stress (Figures 1(b) and 1(c)). The lower Na+/K+ ratio maintained by N119 should have conferred a less stressed cellular environment than that by “Kirariboshi.” This response agreed with the previously published observations, in which both salt tolerant rice and foxtail millet cultivars were found to maintain a low Na+/K+ ratio in their shoot tissues [43, 44].

Figure 1.

Ion contents in the leaves of B. napus in response to salt stress. Symbol “∗∗” indicates significant difference at P < 0.01 by t-test.

3.2. Time Point for Transcriptome Analysis

The expression levels of four salt-responsive genes, that is, BnBDC1 [22], BnLEA4 [23], BnMPK3 [45], and BnNAC2 [46], were analyzed in order to determine the most appropriate time point(s) for transcriptome analysis of N119. Generally, the expression showed more than 2-fold upregulation at 1 h after stress and subsequent downregulation at the following time points (Additional file 2). However, some genes were observed to maintain the upregulated expression at 12 h and 24 h after stress. Together with the phenotypic data, that is, Na+ content, the ratio of Na+/K+, and the ratio of Na+/Ca2+, transcriptome regulation of salt stress was analyzed at 1 h and 12 h after stress.

3.3. Nucleotide Sequencing and De Novo Assembly

Although nonredundant unigenes of B. napus are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), the coverage of these data in the whole transcriptome of B. napus is uncertain. Since B. napus whole genome sequences and annotations of B. napus are not available at present, reference-based transcriptome analysis is also not feasible for B. napus. Therefore, de novo assembly appears to be a good approach to study salt regulated expression changes in this species.

For a broad survey of salt-responsive genes, eight cDNA libraries were prepared from mRNA from the leaves and the roots of the control and salt-treated plants, denoted as BnLc (leaves of control plants), BnLs (leaves of salt-treated plants), BnRc (roots of control plants), and BnRs (roots of salt-treated plants) sampled at 1 h and 12 h and sequenced by Illumina deep-sequencing. After removal of low quality and adapter sequences, nearly 211 million clean reads remained for all eight transcriptomes. The percentages of Q20 bases for the clean reads in all eight transcriptomes were all above 96% (Additional file 3). In sum, the clean reads constituted ~38 GB of sequence data.

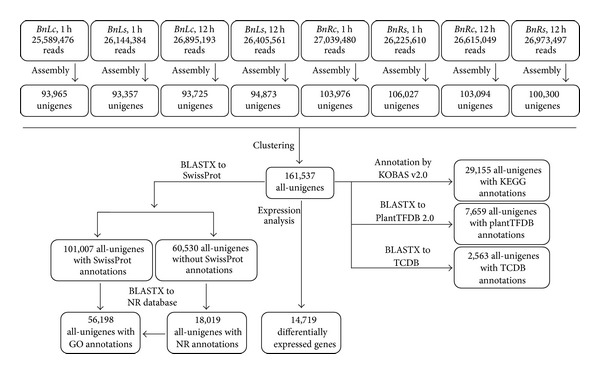

De novo assembly was carried out by the Trinity method [27] and nonredundant sequences were obtained by clustering using CD-HIT-EST [28] (Figure 2). From now on, the clustered unigene sequences are herein referred to as all-unigenes. Overviews of assembly results are shown in Tables 1 and 2. These sequence reads were finally clustered to 161,537 nonredundant all-unigenes, spanning a total of 112 Mb of sequences (Table 3, Figure 2). All the all-unigenes were longer than 200 bp. Mean length and N50 of the final all-unigenes were 693 bp and 1,039 bp, respectively. By the Trinity de novo assembly method, no “N,” that is, unidentified nucleotide, remained in the final unigenes. Due to an unexpectedly large number of all-unigenes obtained after clustering, de novo assembly was performed again by the SOAPdenovo program version 1.04 [29]. Clustering of the SOAPdenovo unigene sequences yielded 191,237 nonredundant sequences. Nevertheless, the assembly quality was worse than that by the Trinity method. All-unigenes generated by SOAPdenovo had a mean length of 506 bp and N50 of 592 bp, and 25% of the all-unigenes had at least one “N” (Additional file 4). The results were similar to those of transcriptome assembly reports of Aegilops variabilis [47] and Chorispora bungeana [48], in which the assembly qualities of the Trinity method were superior to those of the SOAPdenovo method. All-unigenes generated by both Trinity and SOAPdenovo were searched against the B. napus nonredundant unigenes from NCBI. The Trinity all-unigenes corresponded to 61,015 B. napus nonredundant unigenes from NCBI, while the SOAPdenovo all-unigenes had 58,357 hits. Therefore, the assembly results from the Trinity method were used for all of the following analyses.

Figure 2.

Flowcharts of the transcriptome analysis for B. napus. The whole analysis involved sequencing assembly by Trinity and clustering by CD-HIT-EST, SwissProt/Nr annotation, GO annotation, KEGG annotation, aligning to PlantTFDB 2.0 and TCDB, and identification of DEGs as candidate salt-responsive genes.

Table 1.

Statistics of the assembled unigene of leaf transcriptomes by Trinity method.

| Length of unigenes (bp) | BnLc, 1 h | BnLs, 1 h | BnLc, 12 h | BnLs, 12 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200–500 | 50,045 | 47,745 | 45,156 | 46,571 |

| 500–1000 | 26,937 | 26,584 | 26,585 | 27,125 |

| 1000–1500 | 10,689 | 11,320 | 12,355 | 12,286 |

| 1500–2000 | 4,016 | 4,721 | 5,645 | 5,397 |

| >2000 | 2,278 | 2,987 | 3,984 | 3,494 |

|

| ||||

| Total unigenes | 93,965 | 93,357 | 93,725 | 94,873 |

| Mean length (bp) | 646 | 682 | 732 | 711 |

| N50 (bp) | 861 | 933 | 1,025 | 986 |

| Total length (bp) | 60,699,848 | 63,664,784 | 68,579,723 | 67,428,136 |

Table 2.

Statistics of the assembled unigene of root transcriptomes by Trinity method.

| Length of unigenes (bp) | BnRc, 1 h | BnRs, 1 h | BnRc, 12 h | BnRs, 12 h |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200–500 | 54,493 | 55,680 | 50,825 | 52,290 |

| 500–1000 | 28,077 | 27,208 | 27,408 | 27,384 |

| 1000–1500 | 12,275 | 12,638 | 13,450 | 12,097 |

| 1500–2000 | 5,606 | 5,928 | 6,539 | 5,137 |

| >2000 | 3,525 | 4,573 | 4,872 | 3,392 |

|

| ||||

| Total unigenes | 103,976 | 106,027 | 103,094 | 100,300 |

| Mean length (bp) | 682 | 703 | 737 | 679 |

| N50 (bp) | 956 | 1,014 | 1,072 | 947 |

| Total length (bp) | 70,938,630 | 74,504,289 | 76,016,194 | 68,138,136 |

Table 3.

Statistics of the clustered all-unigene by CD-HIT-EST.

| Length of unigenes (bp) | All-unigene |

|---|---|

| 200–500 | 89,041 |

| 500–1000 | 37,426 |

| 1000–1500 | 18,623 |

| 1500–2000 | 9,230 |

| >2000 | 7,217 |

|

| |

| Total unigenes | 161,537 |

| Mean length (bp) | 693 |

| N50 (bp) | 1,039 |

| Total length (bp) | 111,953,629 |

3.4. Functional Annotation of All-Unigenes of Brassica napus

Annotation of all-unigenes was performed by searching them against the SwissProt database. Among the 161,537 all-unigenes, 101,007 (62.5%) had at least one hit to the SwissProt database in BLASTX search with E value ≤1 × 10−5 (Additional file 5, sheet 1). The NCBI nonredundant (NR) protein database was searched for the remaining all-unigenes without a SwissProt hit and 18,019 (11.2%) of all-unigenes showed significant similarity to their respective subjects at E value ≤1 × 10−5 (Additional file 5, sheet 1). Overall, these all-unigenes matched 41,169 unique protein accessions (30,401 for SwissProt and 10,768 for NR hit). Only 57.9% of the all-unigenes shorter than 500 bp had BLAST hits in either the SwissProt or NR database (Additional file 6). The proportion of all-unigenes hit with BLAST increased markedly in those with larger sizes.

Functional classifications of gene ontology (GO) terms of all unigenes are shown in Additional file 6. In total, 56,198 out of 119,026 all-unigenes with either SwissProt hits or NCBI NR hits were assigned to GO terms (Figure 2). In the category of “Biological Process,” the largest groups were of “cellular process,” “metabolic process,” “biological regulation,” and “response to stimulus” (Additional file 7). In the category of “Molecular Function,” “binding” and “catalytic” activities were the largest group. In the category of “Cellular Component,” most of the all-unigenes were located in “cell” and “organelle.” In order to further understand the biological function and interaction of genes, pathway-based analysis was performed based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genome (KEGG) Pathways database, which documents the networks of molecular interaction in the cells and variants of them specific to particular organisms. All-unigenes were mapped against the KEGG Ontology (KO) database by BLASTX. Mapped all-unigenes were annotated by KOBAS v2.0 [36]. We performed KEGG pathway analysis to assign the all-unigenes to biological pathways. In total, 29,155 all-unigenes were assigned to 245 pathways. These pathways belonged to 25 clades under 5 major KEGG categories, that is, “Metabolism,” “Genetic information processing,” “Cellular process,” “Environmental information processing,” and “Organism systems” (Additional file 8). Among these pathways, “plant hormone signal transduction,” “spliceosome,” “oxidative phosphorylation,” “RNA transport,” and “protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum” were the top five pathways represented by all-unigenes.

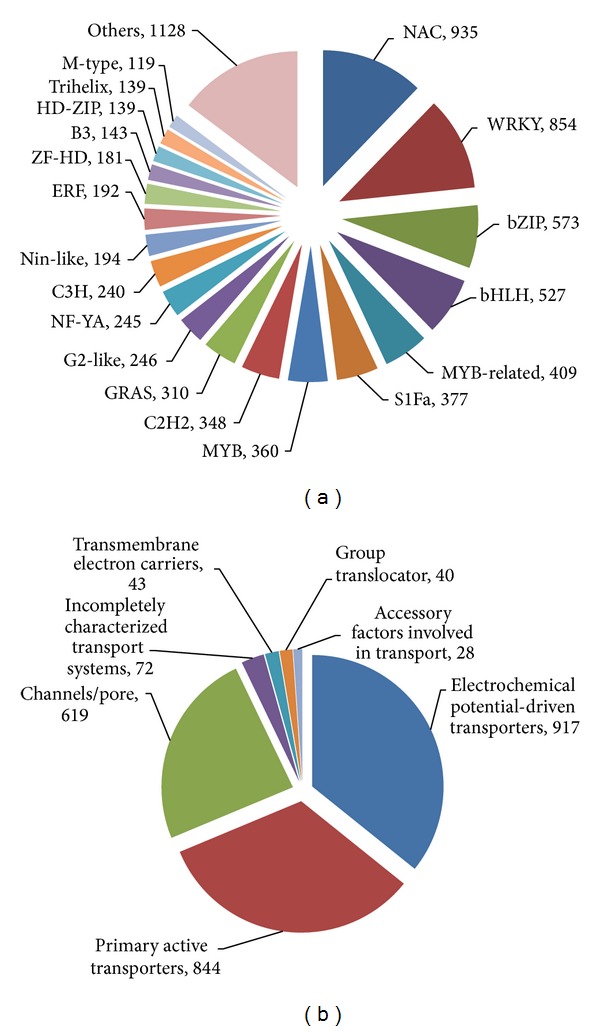

Searching against the Plant Transcription Factor Database v2.0 (PlantTFDB 2.0) [37] matched 7,659 all-unigenes to 57 unique transcription factor (TF) gene families (Figure 3(a); >Additional file 4, sheet 2). In total, these putative B. napus transcription factor genes represent 4.72% of the total transcripts. The overall percentage distribution of transcripts encoding transcription factors among the various known protein families is similar to those in Arabidopsis thaliana and B. rapa published earlier [37] (Additional file 9). However, the number of genes increased for a few families, such as NAC, WRKY, S1Fa-like, GRAS, NF-YA, Nin-like, and ZF-HD. Interestingly, some transcription factor families absent in B. rapa were found in Brassica napus in this study, for example, NF-X1, CAMTA, CPP, HB-PHD, and SAP. These observations indicate the evolutionary significance among these species. In addition, a BLASTX search against the transporter classification database (TCDB) [38, 39] identified 2,563 transporter genes in all-unigenes (Figure 3(b); Additional file 5, sheet 3). The majority of the transporter genes belonged to “Electrochemical potential-driven transporters,” “Primary active transporters,” and “Channel/pores.”

Figure 3.

Classification of transcription factor and transporter gene families in B. napus. (a) Distribution of transcription factor gene families in B. napus. (b) Distribution of transporter gene families in B. napus.

3.5. Identification of DEGs

Two criteria of screening threshold were applied to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs); that is, (i) the average of fold change in gene expression level was more than or equal to 2-fold between salt-treated and distilled water-treated samples and (ii) the false discovery rate (FDR) was less than 0.01. Under these criteria, 14,719 out of 161,537 all-unigenes were found to be differentially expressed in at least one tissue at one condition (Additional file 10). Overall, the number of DEGs was greater in the roots (8,665 DEGs) than those in the leaves (7,795 DEGs) (Additional file 11). There were also many more DEGs which responded at 1 h after stress (9,242 DEGs) than those at 12 h (7,635 DEGs). In both the leaves and the roots, the number of upregulated DEGs by salt treatment was more prominent than that of downregulated DEGs. Only a subset of DEGs shared a common tendency of expression changes between both organs, that is, 432 upregulated and 110 downregulated at 1 h after stress and 133 upregulated and 134 downregulated at 12 h after stress (Additional file 11). A relatively small portion of DEGs showed an opposite tendency of expression changes between the two organs, that is, 120 DEGs upregulated in the leaves but downregulated in the roots and 96 DEGs downregulated in the leaves but upregulated in the roots at 1 h after stress; 115 DEGs upregulated in the leaves but downregulated in the roots and 97 DEGs downregulated in the leaves but upregulated in the roots at 12 h after stress. The remaining majority of DEGs were distinctly upregulated or downregulated in either the leaves or the roots.

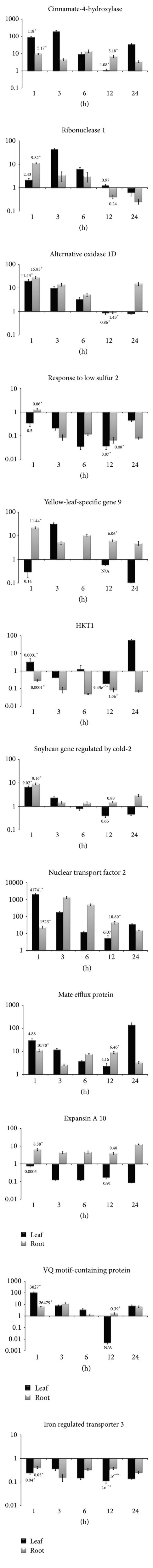

3.6. Validation of DEGs by Semi qRT-PCR and Real-Time qPCR

To validate the reliability of our sequencing approach in identifying salt-responsive DEGs, 40 randomly selected DEGs for eight conditions, that is, 23 DEGs at 1 h and 13 DEGs at 12 h in the leaves and 26 DEGs at 1 h and 13 DEGs at 12 h in the roots, were tested by semi qRT-PCR (Additional file 12). These DEGs consisted of previously discovered salt-responsive genes, genes encoding ion transport proteins, and novel salt-responsive genes. The novel salt-responsive genes tested in this study were Nuclear Transport Factor 2, PQ-loop Repeat Family Protein, Response to Low Sulfur 2, Yellow-Leaf-Specific Gene 9, Ribonuclease 1, VQ-motif Containing Protein, and some unknown proteins. The semi qRT-PCR profiles of these DEGs were basically in agreement with the RNA-seq results. Among these DEGs, expression trends of 12 DEGs were further evaluated by real-time qRT-PCR at 1 h, 3 h, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h (Figure 4). Although the expression fold change differed a little between the RNA-seq and qRT-PCR, the patterns were similar.

Figure 4.

Validation of DEGs with qRT-PCR. The x-axis represents hours after stress while the y-axis represents salt-induced expression fold change relative to control treatment (0 mM). The number of label above the bar is fold change obtained from RNA-seq data. Symbol “∗” indicates FDR < 0.01.

To investigate whether Kirariboshi has the similar expression fold change of salt-responsive DEGs to that of N119, qRT-PCR analyses for some DEGs were carried out. The result indicated that Kirariboshi showed similar regulation of the expression fold change for most of the DEGs to that in N119 (Additional file 13).

3.7. Functional Characterization of DEGs

To further characterize the expression changes in these two organs at two time points, GO enrichment analysis was conducted for the DEGs with the whole transcriptome set as background. The enriched GO terms were also compared between upregulated and downregulated DEGs at each time point after the salt treatment of both organs (Additional files 14–17). In the roots, as the first organ exposed to salt stress, at 1 h after stress, the top five overrepresented GO terms of “Biological Process” for upregulated DEGs were “response to water deprivation,” “response to abscisic acid stimulus,” “response to chemical stimulus,” “hyperosmotic salinity response,” and “response to organic substance” (Additional file 14, sheet 5). Overrepresented GO terms existing in upregulated DEGs at both 1 h and 12 h after stress in the roots were “response to wounding,” “response to chemical stimulus,” “response to organic substance,” “regulation of response to stimulus,” “response to stimulus,” “response to chitin,” “response to stress,” and “oxidoreductase activity” (Additional files 14–17). At 1 h after stress, in the leaves, the top five significantly overrepresented GOs for upregulated DEGs were “response to chitin,” “response to abscisic acid stimulus,” “response to organic substance,” “hyperosmotic salinity response,” and “response to jasmonic acid stimulus” (Additional file 14, sheet 1). Some overrepresented GOs at 1 h after stress in the leaves remained overrepresented for that upregulated at 12 h after stress, for example, “response to abiotic stimulus,” “response to osmotic stress,” “response to cold,” “hyperosmotic salinity response,” “disaccharide transport,” “oligosaccharide transport,” and “response to abscisic acid stimulus” (Additional file 14). However, there were also a number of overrepresented GOs upregulated at 1 h after stress in the leaves that became overrepresented in all-unigenes downregulated at 12 h after stress, for example, “respiratory burst,” “response to chitin,” “response to mechanical stimulus,” “intracellular signal transduction,” “cellular ketone metabolic process,” “defense response,” and “organic acid metabolic process” (Additional file 14). When enriched GO terms of each condition were compared with each other, upregulated DEGs at 1 h after stress in both the leaves and the roots shared the greatest number of the same overrepresented GO terms (49 GO terms) (Additional files 14–17). This indicates that genes of similar functions probably affecting similar pathways were simultaneously regulated and, in this case, upregulated in both the leaves and the roots to overcome salt stress.

Little overlap was observed between the DEGs in the leaves and the roots at both time points. Similar observation has been found in the salt-responsive transcriptome in M. pinnata [15]. Although similar pathways could be affected by salt shock in both organs, certain salt-induced detrimental impacts varied between different parts of a plant. The GO enrichment analysis indicated that many distinct groups of genes were activated exclusively in either the leaves or the roots possibly to overcome salt-inducible damages. For example, at 1 h after stress, many phytohormone related pathways were enriched solely in the leaves, that is, “ethylene mediated signaling pathway,” “regulation of gibberellins biosynthetic process,” and “salicylic acid biosynthetic process” (Additional files 14–17). Conversely, in the root at 1 h after stress, genes involved in synthesis of the cellular component and defense response were distinctly overrepresented, that is, “cell wall assembly,” “cell wall macromolecule catabolic process,” “regulation of defense response,” and “regulation of immune system process” (Additional files 14–17).

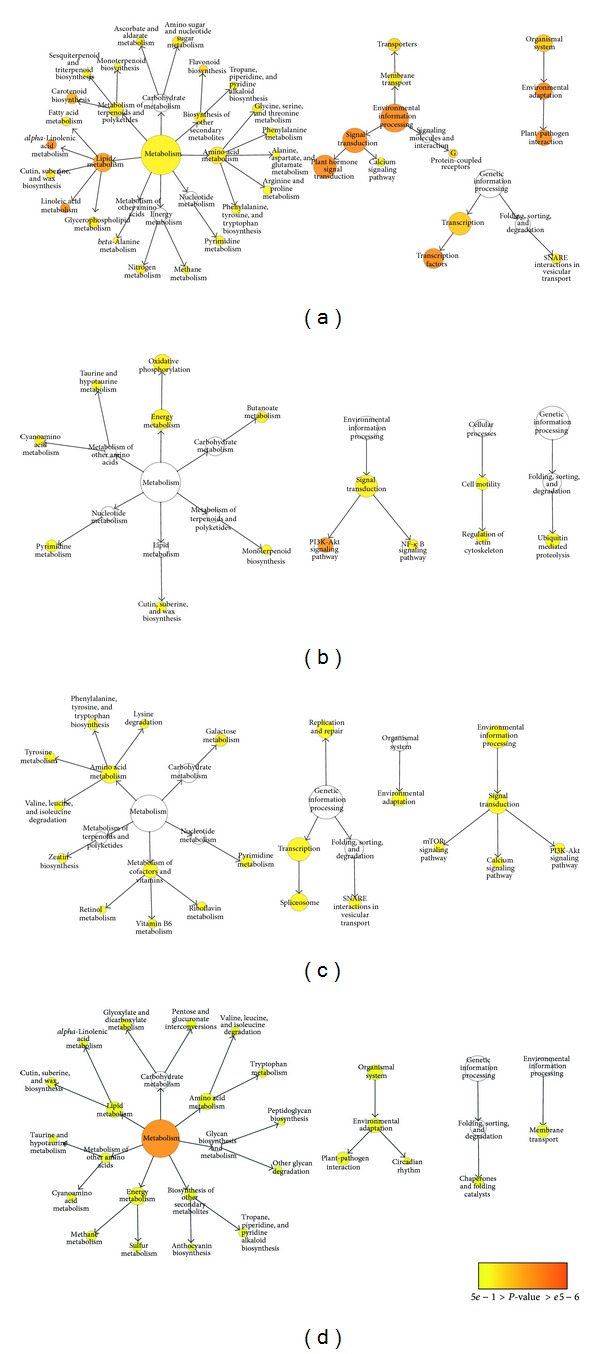

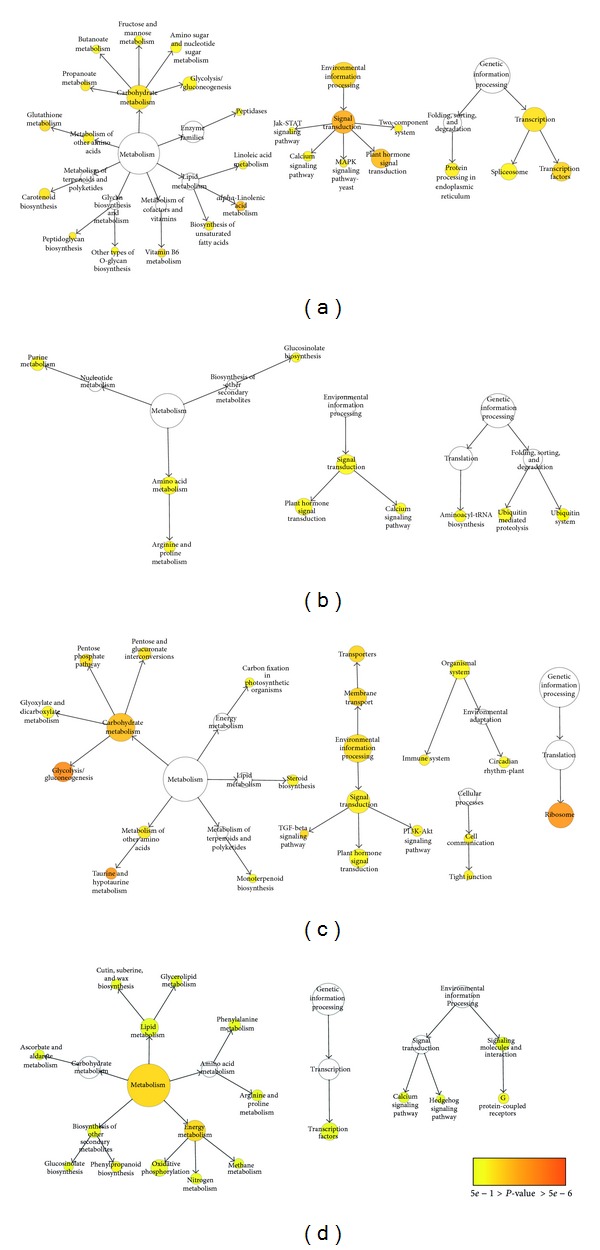

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was also performed to further understand the biological meanings of the response time points of transcripts. Enrichment was considered to be significant at corrected P value < 0.05. In total for both time points, the DEGs were enriched in 19 ontologies and 23 ontologies in the leaves and in the roots, respectively, at corrected P value < 0.05 (Additional file 18; Figures 5 and 6). The KEGG category of “Environmental information processing” was significantly enriched in upregulated root DEGs at both 1 h and 12 h after stress (Additional file 18, sheets 5 and 7; Figures 6(a) and 6(c)). However, different pathways in this category were enriched in the respective upregulated root DEGs at both time points, that is, “plant hormone signal transduction” at 1 h after stress and “transporters” and “TGF-beta signaling pathway” at 12 h after stress. Besides, many pathways in the category of “Metabolism” were enriched at both time points in the roots. In the category of “Metabolism,” the clade of “Carbohydrate metabolism” was overrepresented in the roots at both time points (Additional file 18, sheets 5 and 7). The overrepresentation of “Carbohydrate metabolism” was due to upregulation of several genes involved in “glycolysis/gluconeogenesis,” “fructose and mannose metabolism,” “butanoate metabolism,” “amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism,” and “propanoate metabolism” at 1 h after stress and enrichment of “glycolysis/gluconeogenesis,” “pentose phosphate pathway,” and “pentose and glucuronate interconversions” at 12 h after stress. The changes in KO enrichment in the roots at 1 h and 12 h after stress depicted switches in functional pathway regulation at different time points for salinity adaptation in the roots. In the leaves, the number of overrepresented KO terms was more prominent at 1 h after stress than that at 12 h (Additional file 18, sheets 1–4; Figure 5). At 1 h after stress, a total of seven KO terms significantly enriched in the leaves were also found to be overrepresented in the roots at 1 h after stress (Additional file 18, sheets 1 and 5; Figures 5(a) and 6(a)). This result directly agreed with the GO enrichment analysis, in which both the leaves and the roots shared the most enriched GO terms at 1 h after stress. Generally, the overrepresented KO terms shared between the leaves and the roots at 1 h belong to the clades of “Lipid metabolism,” “Metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides,” “Signal transduction,” and “Transcription.” The KEGG enrichment analysis depicted common, tissue-specific, and time-point-specific patterns of overrepresentation. Overall, this observation demonstrated that various biological substances and signaling molecules are required to cope with salt stress. As more genes were differentially expressed in both organs and more overrepresented GO and KO terms were shared between both organs at 1 h after stress than that at 12 h, DEGs regulated at 1 h after stress were particularly important for salinity adaptation and probably for salt tolerance as well.

Figure 5.

Overrepresented KEGG pathways for DEGs in the leaves. Overrepresented pathways were identified in upregulated DEGs at 1 h after stress (a), downregulated DEGs at 1 h after stress (b), upregulated DEGs at 12 h after stress (c), and downregulated DEGs at 12 h after stress (d), respectively.

Figure 6.

Overrepresented KEGG pathways for DEGs in the roots. Overrepresented pathways were identified in upregulated DEGs at 1 h after stress (a), downregulated DEGs at 1 h after stress (b), upregulated DEGs at 12 h after stress (c), and downregulated DEGs at 12 h after stress (d), respectively.

3.8. Transcription Factors

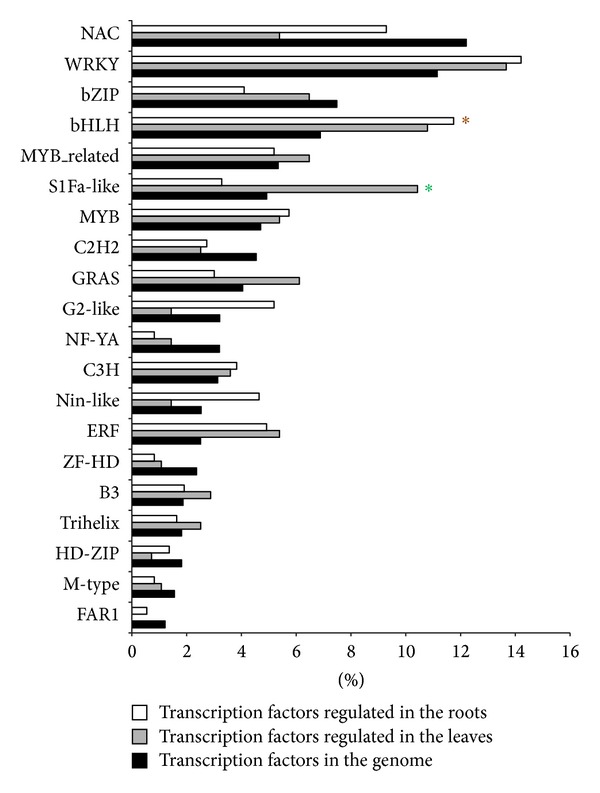

Various transcription factors (TFs) such as AREB/ABF, MYB, AP2/EREBP, bZIP, MYC, HSF, DREB1/CBF, NAC, HB, and WRKY have been shown to orchestrate stress responsive pathways in plants [49, 50]. Based on the putative annotation assigned by homology search with genes in PlantTFDB 2.0, 582 transcription factors representing 45 different families were found to be differentially regulated in both the leaves and the roots at the early stage of salt stress, but only the top 20 differentially regulated TF families are herein shown (Figure 7). These TF families were compared between the leaves and the roots and enrichment analysis was performed to identify families playing vital roles in early stress response.

Figure 7.

Transcription factors families differently expressed in response to salt stress. The percentage means the fraction of the particular transcription factor in the total transcription factors identified in the whole transcriptome or the fraction of certain transcription factors in those regulated in the roots or the leaves. Symbol “∗” indicates overrepresented transcription factor by hypergeometric test at corrected P value < 0.05.

In the leaves, most of the regulated transcription factors belonged to WRKY, bHLH, and S1Fa-like, in which the S1Fa-like transcription factor family was overrepresented (Figure 7). S1Fa binds to a cis-element within both the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter and the promoter of rps1, encoding plastid ribosomal protein S1, and negatively regulates their activity [51]. Other than these two promoters, there was no finding of a novel target regulated by this class of transcription factor. A relatively large number of S1Fa-like transcription factors, that is, 22 genes, were found to be upregulated at 1 h after stress in the leaves of B. napus. It would be interesting to elucidate the salt-responsive target genes potentially regulated by this transcription factor family.

In the roots, the majority of the regulated transcription factors belonged to WRKY, bHLH, and NAC, in which bHLH was overrepresented among the DEGs (Figure 7). These upregulated DEGs annotated as bHLH showed high homology to Arabidopsis ICE2, ROX1, and some bHLH genes from B. rapa. In Arabidopsis, the expression of a bHLH transcription factor, identified as inducer of CBF expression 1 (ICE1), was upregulated by salt stress [52]. Two Arabidopsis bHLH transcription factors, that is, ICE1 and ICE2, were discovered to regulate the transcription of CBF3 and CBF1, respectively, under cold stress. Overexpression of ICE1 and ICE2 enhances the expression of CBF3 and CBF1 and, in turn, improves freezing tolerance [52, 53]. Besides, two homologues of ICE, that is, OrbHLH001 and OrbHLH2, from wild rice (Oryza rufipogon) are salt-inducible and overexpression of these two genes in Arabidopsis has been found to improve tolerance to salt stress [54, 55]. This group of transcription factors was overrepresented in the roots of B. napus at an early stage after salt stress, indicating its possible role in regulating other important salt-responsive genes in this species.

In both the leaves and the roots, WRKY was the most abundant differentially regulated transcription factor in response to salt stress (Figure 7). Most of these upregulated DEGs showed high homology to previously identified WRKY genes in Arabidopsis and B. napus, for example, BnWRKY3, BnWRKY4, BnWRKY11, BnWRKY29, BnWRKY40, and BnWRKY46. Recently, many studies have shown that WRKY genes in wheat [56], soybean [57], Tamarix hispida [58], and Arabidopsis [59] are quickly induced at an early time point of salt stress. Salt-responsive WRKY genes identified in wheat, soybean, and T. hispida also enhance salinity tolerance when overexpressed in plants [56–58]. A total of 13 BnWRKY genes, including BnWRKY11 and BnWRKY40, in B. napus have been found to be responsive to both fungal pathogens and hormone treatments [60]. So far, there has been no finding of WRKY genes in B. napus responsive to salt stress and conferring salinity tolerance. The salt-responsive WRKY genes identified in this study are good candidates for further investigations for their potential roles in salinity tolerance in B. napus.

In addition, a large number of all-unigenes showing homology to various NAC transcription factor genes, for example, BnNAC5-1, ANAC001, ANAC036, ANAC055, and ANAC090, were found to be upregulated in the roots of B. napus at 1 h or 12 h after stress. It has been reported that six NAC genes (BnNAC1-1, BnNAC5-1, BnNAC5-7, BnNAC5-8, BnNAC5-11, and BnNAC14) were upregulated by various biotic and abiotic stresses such as mechanical wounding, insect feeding, fungal infection, cold shock, and dehydration [61]. Overexpression of BnNAC5 in a vni T-DNA insertion mutant with salt-hypersensitive defect recovered the normal phenotype and many stress-responsive genes were enhanced in the BnNAC5 overexpressing lines [46]. Upregulation of several NAC transcription factors in B. napus in the roots and the leaves is considered to be crucial for subsequent induction of stress responsive genes for tolerance.

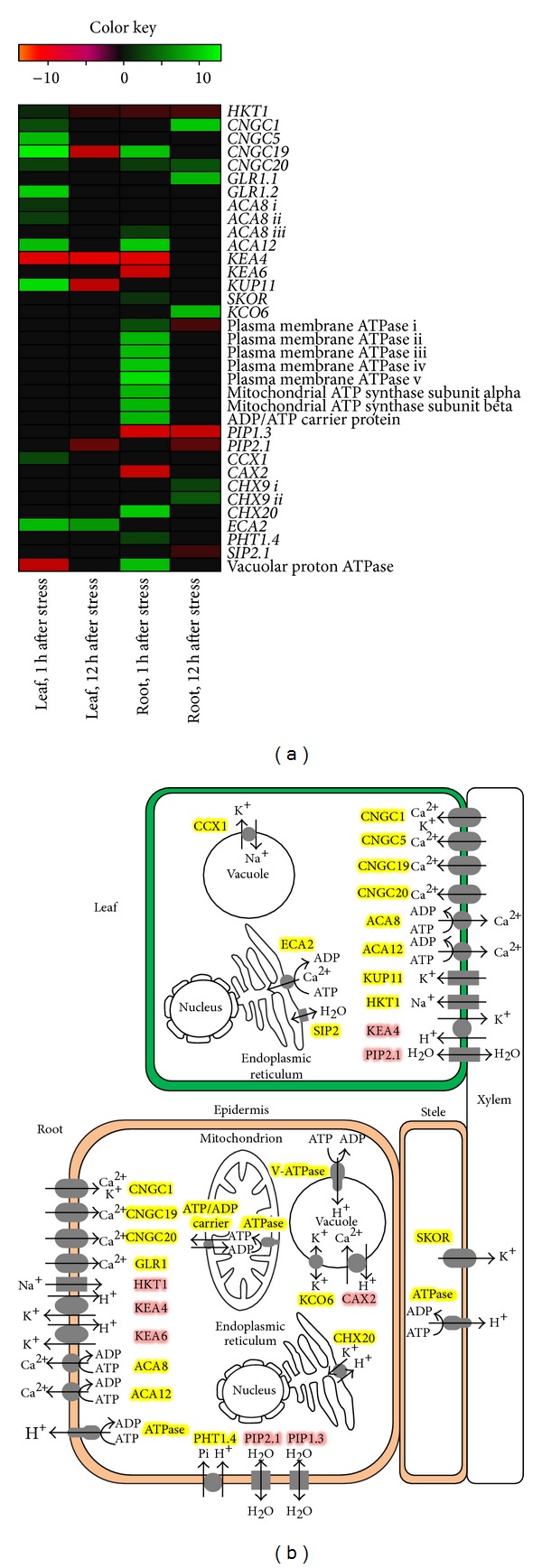

3.9. Regulation of Ion Transporter Genes Involved in Ion Homeostasis

Among the 2,563 transporter genes annotated, 436 were either upregulated or downregulated by salt stress, that is, 231 transporter DEGs in the leaves, 261 DEGs in the roots, and 56 DEGs in both organs. Here, we focus on the regulation of ion transporters with potential functions in ion homeostasis in response to salt stress. The expression changes, subcellular localization, and functions are illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Regulation of transporter genes during salt stress. (a) Heat map depicting log2 fold change of differential expression of transporter genes in B. napus. (b) Cellular localization and functions of the regulated transporter in response to salt stress. Genes highlighted in yellow indicate upregulation while those highlighted in red indicate downregulation.

As shown in Figure 8, HKT1 was found to be downregulated in the roots at an early stage after salt stress but upregulated in the leaves at 1 h after stress. According to our qRT-PCR result, the upregulation of HKT1 was the most prominent in the leaves at 24 h (Figure 4). Na+ enters plant cells through HKT1, the high-affinity K+ transporter, and some other nonselective cation channels. Downregulation of HKT1 in the roots can reduce toxic Na+ influx into the cytosol. However, upregulation of HKT1 expression in the leaves would further enhance salt tolerance of this B. napus line. It has been demonstrated that AtHKT1;1 is localized at the plasma membrane of xylem parenchyma cells in the shoots [62]. Previous study has shown both reduced phloem Na+ and elevated xylem Na+ in the shoots of hkt1;1 mutants, thus indicating that AtHKT1;1 functions primarily to transport Na+ from the xylem into xylem parenchyma cells, at least in the shoots. Retrieval of Na+ from the xylem in the shoots reduces net Na+ influx into the shoots [63]. Based on this model, upregulation of HKT1 in the leaves of this B. napus line possibly reduces Na+ transport into the leaves for salt tolerance.

Several transporters involved in cellular Ca2+ regulation exhibited differential expression. Expressions of many cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels (CNGC) were found to be upregulated in both the leaves and the roots of B. napus (Figure 8). The glutamate receptors (GLR) were also upregulated in both organs by salt stress. Many of these CNGC and GLR molecules function in transporting Ca2+ into the cytosol. Some of these ion channels are also responsible for maintenance of cellular K+ content. Well-known initial responses of plant cells to salt stress are the generation of transient cytosolic Ca2+ flux and the subsequent activation of Ca2+ sensor proteins [62]. High concentrations of Na+ in external solution cause decreases in cellular K+ and Ca2+ contents of many plant species [64, 65], sometimes to certain extent resulting in K+ and Ca2+ deficiencies [66, 67]. It has been reported that the expression of AtCNGC1 restored the Ca2+ conducting activity of a Ca2+ uptake-deficient mutant in response to mating pheromone [68]. The expression of AtCNGC1 in K+ uptake deficient mutants of yeast and Escherichia coli enhanced growth of these mutants and increased intracellular [K+]. The increased expression of CNGC and GLR at an early stage of salt stress may demonstrate their putative contribution to cellular [K+] and [Ca2+] maintenance in B. napus.

Furthermore, two calcium-transporting ATPases homologous to Arabidopsis ACA8 and ACA12 were upregulated in the leaves and the roots in B. napus in response to salt treatment (Figure 8). The Ca2+-ATPase genes from Arabidopsis (ACA12) and the moss Physcomitrella patens (PCA1) have been shown to be upregulated after salt treatment [69, 70]. It has been proposed that Ca2+-ATPase is required to restore the [Ca2+]cyt to prestimulus levels for generation of a specific transient increase in [Ca2+]cyt essential for activation of signaling pathways related to abiotic stress [70]. It has been revealed that the moss PCA1 loss-of-function mutants failed to generate a salt-induced transient Ca2+ peak and exhibited sustained elevated [Ca2+]cyt in response to salt treatment, while WT moss showed transient Ca2+ elevation followed by restoration to prestress level [70]. The PCA1 mutants were also more susceptible to salt stress and displayed a decreased expression level of stress-responsive genes [70]. Besides, a recent study has reported that the aca8 and aca10 mutant plants displayed decreased Flg22-triggered Ca2+ influx and ROS accumulation [71]. Therefore, an increased ACA8 and/or ACA12 expression in B. napus suggested their putative involvements in transient Ca2+ influx for subsequent activation of the signaling pathway essential for salinity tolerance.

K+ efflux antiporters (KEAs) were found to be downregulated in the leaves (KEA4) and in the roots (KEA4, KEA6) (Figure 8). The role of KEAs in ion homeostasis is poorly understood. Downregulation of these antiporters suggests restriction of the efflux of K+ out of the cellular compartment to maintain the cellular K+ level if it is localized at the plasma membrane. Localization of KEAs in B. napus or Arabidopsis and functional characterization using heterologous expression systems are necessary to determine their physiological roles. Another K+ transporter, KUP11, was upregulated at 1 h after stress in the leaves. KUP11 has previously been found to be upregulated by salt stress in Arabidopsis shoots [72]. An increase of transcripts of KUP1 and KUP4 homologues has also been found in the ice plant (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum) during K+ starvation and salt exposure [73]. Upregulation of KUP11 in the leaves in B. napus may contribute to maintenance of cytoplasmic K+ levels and turgor regulation during stress conditions, where external Na+ inhibits K+ uptake and cellular Na+ replaces K+. In addition, a shaker-type potassium channel (SKOR) was upregulated in the roots (Figure 8). In Arabidopsis, substantial salt-induced upregulation of SKOR in roots has been observed [72]. The SKOR channel mediates K+ release into the xylem channel [74]. Upregulation of both SKOR in roots and AKT2/3 in shoots would also result in increased rates of K+ circulation through vascular tissue, pointing towards a long distance redistribution of K+ between the roots and shoots [75]. Upregulation of SKOR in the roots of B. napus is considered to be important in K+ homeostasis under saline conditions by promoting K+ circulation throughout the vascular tissue. In the roots of B. napus, a gene for vacuolar membrane-localized KCO6/TPK3 was also upregulated at an early stage of salt stress. In tobacco, a KCO6 homolog, NtTPK1 was increased ~2-fold by salt stress [76]. Expression of NtTPK1 in mutant E. coli deficient in three major K+ uptake systems rescued its phenotype [76]. Based on the above finding, upregulation of KCO6/TPK3 in B. napus may be involved in transporting K+ into the cytosol resulting in alleviation of salt stress.

Expressions of a number of plasma membrane ATPase genes were upregulated in the roots of B. napus at 1 h after stress (Figure 8). In plant cells, primary active transport mediated by H+-ATPases and secondary transport mediated by channels and cotransporters are crucial to maintain characteristically high concentrations of K+ and low concentrations of Na+ in cytosol. Plasma-membrane H+-ATPase generates driving force for Na+ transport by SOS1 during salt stress [77]. Disruption of the root-endodermis-specific plasma-membrane H+-ATPase, that is, AHA4, in mutant Arabidopsis plants has also been found to enhance salt sensitivity [78]. The transcript levels of some H+-ATPases have also been shown to increase in response to salt stress [79].

In the roots, the transcription of mitochondrial ATP synthase α- and β-subunit together with ATP/ADP carrier was significantly upregulated at 1 h after stress (Figure 8). In wild-type yeast, NaCl stress increases both the mitochondrial F1F0-ATPase activity and expression of the F1F0-ATPase α-subunit [80]. Mitochondrial F1F0-ATPase activity in an aluminium tolerant wheat variety was also found to increase along with Al concentration although the α-subunit transcript remained constant [81]. Upregulation of both ATP synthase subunit and ATP/ADP carrier might correlate with the increase of F1F0-ATPase activity in the roots. Perhaps these upregulations facilitate increased ATP synthesis and the transport rate of ATP into cytosol for regulation of various cellular processes and active transport for adjustment to salt stress.

Salt treatment also downregulated the expression of plasma membrane-localized aquaporin PIP genes in both the leaves and the roots of B. napus at early stage of salt stress (Figure 8). Aquaporins are water channel proteins, which facilitate passive movement of water molecules down a water potential gradient [82]. Most of the water transport in plants occurs via aquaporins. Overexpression of Arabidopsis plasma membrane aquaporin, PIP1b, in tobacco enhances growth rate, transpiration rate, stomatal density, and photosynthetic efficiency under favorable growth conditions [83]. Conversely, overexpression of this aquaporin protein does not seem to have a beneficial effect under salt stress, and transgenic plants wilt faster than wild-type plants under drought stress [83]. Since overexpression of PIP results in enhanced symplastic water transport and increases stomatal density, such conditions are detrimental for plants growing under abiotic stresses. Downregulation of PIP in both the leaves and the roots might assist plants to cope with salt stress by limiting symplastic water transport and transpiration rate to prevent water loss.

A gene with high similarity to cation calcium exchanger, CCX1, in Arabidopsis was found to be upregulated in the leaves of this B. napus line. There are five CCX homologs (CCX1 to CCX5) in Arabidopsis and both CCX3 and CCX4 have been functionally characterized [84]. Expression of Arabidopsis AtCCX3 and AtCCX4 in mutant yeast suppressed its mutant defective phenotypes in Na+, K+, and Mn2+ transport [84]. Subcellular localization indicates that AtCCX3 is accumulated in plant tonoplast [84]. Expression of AtCCX3 increases in plants treated with NaCl, KCl, and MnCl2. Similar to AtNHX1-overexpressing plants, AtCCX3-expressing lines accumulate higher Na+ [84]. However, since AtCCX3-expressing plants did not appear to be salt tolerant, AtCCX3-expressing lines did not completely resemble AtNHX1-expressing plants. Therefore, it was hypothesized that overexpression of AtCCX3 disrupts tonoplast V-type H+ translocating ATPase activity, causing a general disruption in pH homeostasis [84]. AtCCX3 has been suggested to be an endomembrane-localized H+ dependent K+ transporter with apparent Na+ and Mn2+ transport properties [84]. There is a possibility that CCX1 expressed in B. napus functions in sequestration of Na+ into vacuoles and in ion homeostasis. Function characterization of CCX1 in either Arabidopsis or B. napus is necessary to elucidate its involvement in salinity tolerance.

4. Conclusions

A comprehensive transcriptome of B. napus was characterized in both the leaves and roots by the Illumina sequencing technology. This transcriptome modulated by sudden increased salinity or salt shock expands our vision of the regulatory network involved in salinity adaptation in this amphidiploid. The candidate salt-responsive genes identified in B. napus included both the previously reported salt-responsive genes and some novel differentially regulated genes by salt stress, such as S1Fa-like transcription factor genes, some transporter genes, and some unknown protein genes, which will be a new resource for molecular breeding in crops. The molecular functions of many newly identified salt-responsive DEGs were still unknown. Transgenic assay, complementation assay, and subcellular localization could be employed to elucidate their possible contribution in salinity tolerance.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary file 1 is primer pair for qRT-PCR analysis. Supplementary file 2 indicates expression fold change of salt responsive gene markers in B. napus. Supplementary file 3 and 4 are tables indicating summary of sequencing output and statistics for the unigene of B. napus assembled by SOAPdenovo, respectively. Supplementary file 5 reveals annotations of all-unigenes. Supplementary file 6 is a graph depicting length distribution of the all-unigenes with SwissProt or NR annotations. Supplementary file 7 and 8 are GO and KEGG ontology classifications of all-unigenes, respectively. Supplementary file 9 shows comparison of transcription factor families between B. napus, Arabidopsis and B. rapa. Supplementary file 10 indicates log2 fold-changes of DEGs in the leaves and the roots at 1h and 12h. Supplementary file 11 shows Venn diagrams depicting number of DEGs regulated in the leaves and the roots of B. napus. Supplementary file 12 shows the result of validation of DEGs by semi-qRT-PCR. Supplementary file 13 shows the comparison of expression fold-change for DEGs between N119 and Kirariboshi. Supplementary file 14 lists all over-represented GO terms in DEGs. Supplementary file 15, 16 and 17 indicate comparison of over-represented GO terms of “Biological Process”, “Molecular Function”, and “Cellular Component”, respectively in the leaves and the roots at 1h and 12h after stress. Supplementary file 18 lists all over-represented KEGG ontology in DEGs.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the management of ACGT Sdn. Bhd. for permission to utilize the bioinformatics facilities. The authors would also like to thank the members of ACGT's Bioinformatics team for technical assistance. B. napus cv. “Kirariboshi” was kindly provided by the Tohoku Agricultural Research Center, Japan. This work was supported in part by the Japan-China Joint Research Program of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (J120000331) and the Rapeseed Project for Restoring Tsunami-Salt-Damaged Farmland. Hui-Yee Yong is a recipient of the Japanese Government (Monbukagakusho: MEXT) Scholarship from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contribution

Hui-Yee Yong and Zhongwei Zou designed the experiment and performed sample collection and RNA extraction. Hui-Yee Yong and Shiori Nasu analyzed the ion contents. Hui-Yee Yong, Eng-Piew Kok, Bih-Hua Kwan, and Kingsley Chow performed bioinformatics analyses. Hui-Yee Yong performed RT-PCR analysis and drafted the paper. Hiroyasu Kitashiba advised in experimental design. Masami Nanzyo assisted in ion content analysis. Takeshi Nishio supervised Hui-Yee Yong, coordinated the project, and edited the paper. All authors read and approved the final paper.

References

- 1.Rengasamy P. Soil processes affecting crop production in salt-affected soils. Functional Plant Biology. 2010;37(7):613–620. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruan CJ, da Silva JAT, Mopper S, Qin P, Lutts S. Halophyte improvement for a salinized world. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 2012;29(6):329–359. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Munns R. The impact of salinity stress. 2013, http://www.plantstress.com/Articles/salinity_i/salinity_i.htm.

- 4.Toews-Shimizu J. Rice in Japan: beyond 3.11. Rice Today. 2012;11(5):20–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashraf M, Bokhari MH, Mahmoud S. Effects of four different salts on germination and seedling growth of four Brassica species. Biologia. 1989;35(2):173–187. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashraf M. Breeding for salinity tolerance in plants. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 1994;13(1):17–42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nasu S, Kitashiba H, Nishio T. ‘Na-no-hana Project’ for recovery from the tsunami disaster by producing salinity-tolerant oilseed rape lines: selection of salinity-tolerant lines of Brassica crops. Journal of Integrated Field Science. 2012;9:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagaharu U. Genome analysis in Brassica with special reference to the experimental formation of B. napus and peculiar mode of fertilization. The Journal of Japanese Botany. 1935;7:389–452. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malik RS. Prospects for Brassica carinata as an oilseed crop in India. Experimental Agriculture. 1990;26(1):125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 10.He T, Cramer GR. Growth and mineral nutrition of six rapid-cycling Brassica species in response to seawater salinity. Plant and Soil. 1992;139(2):285–294. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar D. Salt tolerance in oilseed brassicas-present status and future prospects. Plant Breeding Abstracts. 1995;65(10):1439–1447. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ashraf M, McNeilly T. Responses of four Brassica species to sodium chloride. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 1990;30(4):475–487. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong Q, Li P, Ma S, Rupassara SI, Bohnert HJ. Salinity stress adaptation competence in the extremophile Thellungiella halophila in comparison with its relative Arabidopsis thaliana . The Plant Journal. 2005;44(5):826–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taji T, Seki M, Satou M, et al. Comparative genomics in salt tolerance between Arabidopsis and Arabidopsis-related halophyte salt cress using Arabidopsis microarray. Plant Physiology. 2004;135(3):1697–1709. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.039909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang J, Lu X, Yan H, et al. Transcriptome characterization and sequencing-based identification of salt-responsive genes in Millettia pinnata, a semi-mangrove plant. DNA Research. 2012;19(2):195–207. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dss004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology. 2010;28(5):511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okoniewski MJ, Miller CJ. Hybridization interactions between probesets in short oligo microarrays lead to spurious correlations. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7(1, article 276) doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Royce TE, Rozowsky JS, Gerstein MB. Toward a universal microarray: prediction of gene expression through nearest-neighbor probe sequence identification. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;35(15) article e99 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Xi Y, Yu J, Dong L, Yen L, Li W. A statistical method for the detection of alternative splicing using RNA-seq. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008529.e8529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oshlack A, Robinson MD, Young MD. From RNA-seq reads to differential expression results. Genome Biology. 2010;11(12, article 220) doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-12-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao M, Allard G, Byass L, Flanagan AM, Singh J. Regulation and characterization of four CBF transcription factors from Brassica napus . Plant Molecular Biology. 2002;49(5):459–471. doi: 10.1023/a:1015570308704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu S, Zhang L, Zuo K, Li Z, Tang K. Isolation and characterization of a BURP domain-containing gene BnBDC1 from Brassica napus involved in abiotic and biotic stress. Physiologia Plantarum. 2004;122(2):210–218. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalal M, Tayal D, Chinnusamy V, Bansal KC. Abiotic stress and ABA-inducible Group 4 LEA from Brassica napus plays a key role in salt and drought tolerance. Journal of Biotechnology. 2009;139(2):137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar G, Purty RS, Sharma MP, Singla-Pareek SL, Pareek A. Physiological responses among Brassica species under salinity stress show strong correlation with transcript abundance for SOS pathway-related genes. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2009;166(5):507–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L, Ren F, Zhong H, Jiang W, Li X. Identification and expression analysis of genes in response to high-salinity and drought stresses in Brassica napus . Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica. 2010;42(2):154–164. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmp113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shavrukov Y. Salt stress or salt shock: which genes are we studying? Journal of Experimental Botany. 2013;64(1):119–127. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grabherr MG, Haas BJ, Yassour M, et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology. 2011;29(7):644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(13):1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li R, Zhu H, Ruan J, et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Research. 2010;20(2):265–272. doi: 10.1101/gr.097261.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12(1, article 323) doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leng N, Dawson JA, Thomson JA, et al. EBSeq: an empirical Bayes hierarchical model for inference in RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(8):1035–1043. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leng N, Dawson JA, Kendziorski C. EBSeq: An R Package for Differential Expression Analysis Using RNA-seq Data. 2013. http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/devel/bioc/vignettes/EBSeq/inst/doc/EBSeq_Vignette.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conesa A, Götz S, García-Gómez JM, Terol J, Talón M, Robles M. Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(18):3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Conesa A, Götz S. Blast2GO: a comprehensive suite for functional analysis in plant genomics. International Journal of Plant Genomics. 2008;2008:12 pages. doi: 10.1155/2008/619832.619832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ye J, Fang L, Zheng H, et al. WEGO: a web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:W293–W297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xie C, Mao X, Huang J, et al. KOBAS 2.0: a web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39(supplement 2):W316–W322. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang H, Jin J, Tang L, et al. PlantTFDB 2.0: update and improvement of the comprehensive plant transcription factor database. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39(1):D1114–D1117. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saier MH, Jr., Tran CV, Barabote RD. TCDB: the transporter classification database for membrane transport protein analyses and information. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:D181–D186. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saier MH, Jr., Yen MR, Noto K, Tamang DG, Elkan C. The transporter classification database: recent advances. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37, supplement 1:D274–D278. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maere S, Heymans K, Kuiper M. BiNGO : a Cytoscape plugin to assess over-representation of gene ontology categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(16):3448–3449. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thornton B, Basu C. Real-time PCR (qPCR) primer design using free online software. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education. 2011;39(2):145–154. doi: 10.1002/bmb.20461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−∆∆CT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Puranik S, Jha S, Srivastava PS, Sreenivasulu N, Prasad M. Comparative transcriptome analysis of contrasting foxtail millet cultivars in response to short-term salinity stress. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2011;168(3):280–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walia H, Wilson C, Condamine P, et al. Comparative transcriptional profiling of two contrasting rice genotypes under salinity stress during the vegetative growth stage. Plant Physiology. 2005;139(2):822–835. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.065961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu S, Zhang L, Zuo K, Tang D, Tang K. Isolation and characterization of an oilseed rape MAP kinase BnMPK3 involved in diverse environmental stresses. Plant Science. 2005;169(2):413–421. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhong H, Guo QQ, Chen L, et al. Two Brassica napus genes encoding NAC transcription factors are involved in response to high-salinity stress. Plant Cell Reports. 2012;31(11):1991–2003. doi: 10.1007/s00299-012-1311-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu DL, Long H, Liang JJ, et al. De novo assembly and characterization of the root transcriptome of Aegilops variabilis during an interaction with the cereal cyst nematode. BMC Genomics. 2012;13(1, article 133) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao Z, Tan L, Dang C, Zhang H, Wu Q, An L. Deep-sequencing transcriptome analysis of chilling tolerance mechanisms of a subnival alpine plant, Chorispora bungeana. BMC Plant Biology. 2012;12, article 222 doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh KB, Foley RC, Oñate-Sánchez L. Transcription factors in plant defense and stress responses. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2002;5(5):430–436. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shameer K, Ambika S, Varghese SM, Karaba N, Udayakumar M, Sowdhamini R. STIFDB—arabidopsis stress responsive transcription factor dataBase. International Journal of Plant Genomics. 2009;2009:8 pages. doi: 10.1155/2009/583429.583429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Villain P, Clabault G, Mache R, Zhou D-X. S1F binding site is related to but different from the light-responsive GT- 1 binding site and differentially represses the spinach rps1 promoter in transgenic tobacco. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1994;269(24):16626–16630. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chinnusamy V, Ohta M, Kanrar S, et al. ICE1: a regulator of cold-induced transcriptome and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis . Genes and Development. 2003;17(8):1043–1054. doi: 10.1101/gad.1077503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fursova OV, Pogorelko GV, Tarasov VA. Identification of ICE2, a gene involved in cold acclimation which determines freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana . Gene. 2009;429(1-2):98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou J, Li F, Wang J, Ma Y, Chong K, Xu Y. Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor from wild rice (OrbHLH2) improves tolerance to salt- and osmotic stress in Arabidopsis . Journal of Plant Physiology. 2009;166(12):1296–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li F, Guo S, Zhao Y, Chen D, Chong K, Xu Y. Overexpression of a homopeptide repeat-containing bHLH protein gene (OrbHLH001) from Dongxiang Wild Rice confers freezing and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis . Plant Cell Reports. 2010;29(9):977–986. doi: 10.1007/s00299-010-0883-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Niu CF, Wei W, Zhou QY, et al. Wheat WRKY genes TaWRKY2 and TaWRKY19 regulate abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants . Plant, Cell and Environment. 2012;35(6):1156–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou QY, Tian AG, Zou HF, et al. Soybean WRKY-type transcription factor genes, GmWRKY13, GmWRKY21, and GmWRKY54, confer differential tolerance to abiotic stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2008;6(5):486–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zheng L, Liu G, Meng X, et al. A WRKY gene from Tamarix hispida, ThWRKY4, mediates abiotic stress responses by modulating reactive oxygen species and expression of stress-responsive genes. Plant Molecular Biology. 2013;82(4-5):303–320. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0063-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hu Y, Chen L, Wang H, Zhang L, Wang F, Yu D. Arabidopsis transcription factor WRKY8 functions antagonistically with its interacting partner VQ9 to modulate salinity stress tolerance. Plant Journal. 2013;74(5):730–745. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang B, Jiang Y, Rahman MH, Deyholos MK, Kav NNV. Identification and expression analysis of WRKY transcription factor genes in canola (Brassica napus L.) in response to fungal pathogens and hormone treatments. BMC Plant Biology. 2009;9, article 68 doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hegedus D, Yu M, Baldwin D, et al. Molecular characterization of Brassica napus NAC domain transcriptional activators induced in response to biotic and abiotic stress. Plant Molecular Biology. 2003;53(3):383–397. doi: 10.1023/b:plan.0000006944.61384.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sunarpi, Horie T, Motoda J, et al. Enhanced salt tolerance mediated by AtHKT1 transporter-induced Na+ unloading from xylem vessels to xylem parenchyma cells. The Plant Journal. 2005;44(6):928–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knight H, Trewavas AJ, Knight MR. Calcium signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana responding to drought and salinity. The Plant Journal. 1997;12(5):1067–1078. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.12051067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greenway H, Munns R. Mechanisms of salt tolerance in nonhalophytes. Annual Review of Plant Physiology. 1980;31:149–190. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rathert G. Effects of high salinity stress on mineral and carbohydrate metabolism of two cotton varieties. Plant and Soil. 1983;73(2):247–256. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maas EV, Grieve CM. Sodium-induced calcium deficiency in salt-stressed corn. Plant Cell Environ. 1987;10:559–564. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Muhammed S, Akbar M, Neue HU. Effect of Na/Ca and Na/K ratios in saline culture solution on the growth and mineral nutrition of rice (Oryza sativa L.) Plant and Soil. 1987;104(1):57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ali R, Zielinski RE, Berkowitz GA. Expression of plant cyclic nucleotide-gated cation channels in yeast. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006;57(1):125–138. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maathuis FJM, Filatov V, Herzyk P, et al. Transcriptome analysis of root transporters reveals participation of multiple gene families in the response to cation stress. Plant Journal. 2003;35(6):675–692. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qudeimat E, Faltusz AMC, Wheeler G, et al. A PIIB-type Ca2+-ATPase is essential for stress adaptation in Physcomitrella patens . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(49):19555–19560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800864105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.dit Frey NF, Mbengue M, Kwaaitaal M, et al. Plasma membrane calcium ATPases are important components of receptor-mediated signaling in plant immune responses and development. Plant Physiology. 2012;159(2):798–809. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.192575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maathuis FJM. The role of monovalent cation transporters in plant responses to salinity. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006;57(5):1137–1147. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Su H, Golldack D, Katsuhara M, Zhao CS, Bohnert HJ. Expression and stress-dependent induction of potassium channel transcripts in the common ice plant. Plant Physiology. 2001;125(2):604–614. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gaymard F, Pilot G, Lacombe B, et al. Identification and disruption of a plant shaker-like outward channel involved in K+ release into the xylem sap. Cell. 1998;94(5):647–655. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shabala S, Cuin TA. Potassium transport and plant salt tolerance. Physiologia Plantarum. 2008;133(4):651–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2007.01008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hamamoto S, Marui J, Matsuoka K, et al. Characterization of a tobacco TPK-type K+ channel as a novel tonoplast K+ channel using yeast tonoplasts. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(4):1911–1920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhu J. Regulation of ion homeostasis under salt stress. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2003;6(5):441–445. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(03)00085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Vitart V, Baxter I, Doerner P, Harper JF. Evidence for a role in growth and salt resistance of a plasma membrane H+-ATPase in the root endodermis. The Plant Journal. 2001;27(3):191–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Niu X, Zhu J, Narasimhan ML, Bressan RA, Hasegawa PM. Plasma-membrane H+-ATPase gene expression is regulated by NaCl in cells of the halophyte Atriplex nummularia L. Planta. 1993;190(4):433–438. doi: 10.1007/BF00224780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hamilton CA, Taylor GJ, Good AG. Vacuolar H+-ATPase, but not mitochondrial F1F0-ATPase, is required for NaCl tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae . FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2002;208(2):227–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hamilton CA, Good AG, Taylor GJ. Induction of vacuolar ATpase and mitochondrial ATP synthase by aluminum in an aluminum-resistant cultivar of wheat. Plant Physiology. 2001;125(4):2068–2077. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.4.2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kjellbom P, Larsson C, Johansson I, Karlsson M, Johanson U. Aquaporins and water homeostasis in plants. Trends in Plant Science. 1999;4(8):308–314. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01438-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Aharon R, Shahak Y, Wininger S, Bendov R, Kapulnik Y, Galili G. Overexpression of a plasma membrane aquaporin in transgenic tobacco improves plant vigor under favorable growth conditions but not under drought or salt stress. The Plant Cell. 2003;15(2):439–447. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Morris J, Tian H, Park S, Sreevidya CS, Ward JM, Hirschi KD. AtCCX3 is an arabidopsis endomembrane H+-dependent K+ transporter. Plant Physiology. 2008;148(3):1474–1486. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.118810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials