Introduction

Over the past decade, there has been an extensive debate about whether researchers have an obligation to disclose genetic research findings, including primary and secondary findings. There appears to be an emerging (but disputed) view that researchers have some obligation to disclose some genetic findings to some research participants. The contours of this obligation, however, remain unclear.

As this paper will explore, much of this confusion is definitional or conceptual in nature. The extent of a researcher’s obligation to return secondary and other research findings is often limited by reference to terms and concepts like “incidental,” “analytic validity,” “clinical validity,” “clinical relevance,” “clinical utility,” “clinical significance,” “actionability,” and “desirability.” These terms are used in different ways by different writers to describe obligations in different sorts of cases.

Underneath this definitional confusion is a general notion, supported by much of the literature, that findings only need to be disclosed when they surpass certain presumably objective or measureable thresholds, such as medical importance or scientific reproducibility. The problem is that there is significant variability in the way that these terms and concepts are used in the literature and, as such, in defining the scope of an obligation to return findings that surpasses the relevant thresholds.

It is not clear exactly why there has been so much variation in the meaning of these terms. As an initial hypothesis, it could be due to the fact that people have differing views about the ethical foundation(s) supporting an obligation to disclose secondary findings. A range of ethical principles has been proposed to support such an obligation, including beneficence, reciprocity, respect for persons, duty to rescue, duty of ancillary care, and professional responsibility.1 Since any given principle necessarily leads to a more or less expansive view about the scope of the resulting obligation, it stands to reason that the terms employed in articulating these different normative positions might be similarly varied. For example, an obligation rooted in general beneficence might be associated with a more broadly defined conception of clinically valuable findings. In contrast, an obligation tied to the duty to rescue would define this term much more restrictively such that it applied only in cases of genuine rescue and not merely potential benefit.

A second explanation might point to varied beliefs regarding the distinction between research and clinical care. Given the increasing overlap of these two spheres, it is plausible that definitions are so varied because scholars and investigators are influenced by a range of professional orientations, or by differing views about the nature of the research enterprise and the relationship between researchers and subjects. For those who accept something of a blurred line between clinical care and research obligations, there might be a robust belief in the primacy of physicians’ obligations to help the persons in front of them, and a corresponding trust in medical professionals’ ability to appropriately exercise their clinical judgment. Both of these views would obviate the need for narrow definitions. Alternatively, for those more skeptical about collapsing the clinical care/research distinction, there may be a tendency to draw tighter and more careful boundaries around a potential obligation, in order to protect and maximize the production of socially-beneficial generalizable knowledge.

Notwithstanding its causes, a lack of clarity about key terms is impeding progress on the secondary findings debate. One reason is that uncertainty about the meaning of key words limits the formulation of nuanced disclosure frameworks. Tellingly, for example, scholars suggest that an inability to accurately and consistently define “clinical utility” leads to only two alternative disclosure frameworks: never disclosing research findings or always disclosing them.2 Definitional uncertainty also can hinder the implementation of disclosure frameworks, with at least one study reporting that this is impeding communication and decision-making among IRBs, researchers, and research participants.3

The implications of definitional confusion recently have become apparent in the clinical realm, spurred by the controversial 2013 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) Recommendations for Reporting of Incidental Findings in Clinical Exome and Genome Sequencing (ACMG Recommendations). These call for routine examination of a “minimal list of incidental findings” along with the genomic information for which sequencing was sought.4 Yet Wylie Burke and other scholars note that the ACMG Recommendations shift the fundamental concept of an incidental or secondary finding to something requiring “a purposeful analytic effort, above and beyond what is required to answer the clinical question that prompted WGS/WES.”5 Whether the concept of secondary findings is compatible with an active search for such findings remains contentious.

In December 2013, the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues report, Anticipate and Communicate: Ethical Management of Incidental and Secondary Findings, was released, and thus further shifted, and arguably confused, the terminological landscape.6 The Commission recommends demarcating four kinds of findings that fall outside the realm of “primary findings” (in their framing, results that are actively sought using a test or procedure designed to find that result): (1) Anticipatable incidental findings, being findings not actively sought but known to be associated with a test or procedure; (2) Unanticipatable incidental findings, being findings not actively sought that could not have been anticipated given the current state of scientific knowledge; (3) Secondary findings, being findings that are actively sought by a practitioner but not the primary target; and (4) Discovery findings, being results of a broad or wide-ranging test that was intended to reveal anything of interest.7 Since the report was published well after the cut-off point for our literature review (explained below), this article does not analyze these novel classifications further. Yet the Commission’s efforts to split the meaning of so-far synonymous and potentially overlapping terms such as “incidental” and “secondary” findings may add to the prevailing uncertainty about which disclosure obligations apply to what findings.

The goal of this paper is to analyze the definitional muddle underlying the debate about returning genetic research findings, with the hope of answering a few questions. First, what is the range of definitions being used in this debate? Based on an extensive literature review, Part 1 will lay out a range of articulated definitions for each relevant term, with the goal of categorizing them into a handful of distinct types. Part 2 explains the definitional redundancy and confusion in the current literature, and, drawing from the terminological patterns identified in Part 1, outlines more cohesive building blocks to inform the development of future disclosure frameworks. Our minimum goal in articulating these conceptual building blocks is to promote clearer articulations of, and distinctions between, future disclosure frameworks. More ambitiously, we suggest which definitions and conceptualizations we consider most appropriate to use in future disclosure frameworks. Here, we seek to balance benefits to participants through the disclosure of important information with the minimization of undue burdens on individual researchers and the research enterprise more generally.

Our analysis builds upon the central philosophical distinction between concepts and conceptions.8 The basic idea is that the “concept” of X refers to the general (and relatively uncontroversial) structure/shape of X, while various “conceptions” of X are more particular, filled out, and controversial elaborations of the concept. In other words, “concepts” of X will be formal representations of X, while “conceptions” of X will be substantive interpretations of the key elements and relationships operating within that formal framework. (Implicit in this distinction is an important point about the nature of disagreement — namely, that in order for two or more parties to “disagree” about X as opposed to simply talk past one another, there must be at least enough shared agreement about X to know that the parties are referring to the same thing. A concept of X provides this point of common agreement, while competing conceptions of X mark the areas where disagreement arises.) In this paper, we will employ this distinction in a fundamental way to clarify exactly where the primary disagreements arise in the debate over disclosing genetic research findings.

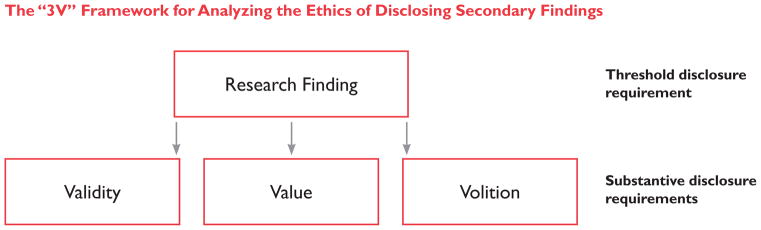

We propose that, underlying all the seeming confusion and disagreement, there are three central and widely agreed upon concepts at work in this debate: validity, value, and volition. The first two concepts concern the nature of the information itself. An obligation to disclose only exists when findings are valid and have value but there are competing conceptions of how to determine or define validity and valuableness. The third concept — volition — pertains not to the information but rather to the person to whom it will be disclosed. Does that person want or not want the information, and what is the best way of determining this? Here, too, competing conceptions arise. Our key point, though, is that almost all of the ethical disagreement arises because of competing conceptions of these three concepts. Understanding and appreciating this key point can help to refocus the substantive debate by providing some common ground to start from in determining how best to interpret these shared concepts. This refocusing can, ideally, produce more productive debate and facilitate some progress in resolving it.

Part 1: Mapping the Current Terminological and Conceptual Landscape

We begin in Part 1 by mapping out how key terms and concepts are used in discussions regarding the ethics of disclosing secondary findings in genetic research. On the basis of a representative (though not exhaustive) literature review involving more than 100 journal articles,9 we catalog the nine most commonly invoked concepts, criteria, and considerations offered in these discussions. As our mapping reveals, the current terminological and conceptual landscape is marked both by extensive diversity of views and by considerable redundancy of terms.

1.1 Secondary Finding

A central term and concept in this debate is “incidental” or “secondary” finding itself. In this paper we use the term “secondary finding” instead of “incidental finding,” agreeing with the reasoning of Christenhusz and her colleagues that to find something you must on some level search for it.10 The descriptor “secondary” also is further removed from questions surrounding a finding’s unexpectedness, which we argue in Part 2 is outdated in the whole-genome sequencing (WGS) era.

The term “secondary finding” is important because the literature frequently draws ethically relevant distinctions based on ideas about the proximal relationship between the finding and the research enterprise. In general, there is usually going to be an obligation to return valid and valuable individual findings that are seen as flowing directly from research, with obligations towards findings with less proximal ties necessarily being less strong. This distinction arose during an earlier research era, where the technological limitations of extant research tests meant that researchers could only focus their inquiries on a targeted set of information (e.g., candidate gene analysis).11 When one is generating a limited set of information, all of which are in service to the research, it seems reasonable to distinguish anticipated findings generated in the course of research from the very rare cases where an unexpected piece of information is generated by, but ancillary to, the research. As evidenced in the analysis below, the literature is rife with varied conceptions of how to draw the distinction between primary and secondary findings. As we will argue in Part 2, this terminology might no longer be appropriate in an era of whole genome sequencing.

A commonly adopted definition coined by Susan Wolf and others in 2008 describes a secondary finding (in their paper, an “incidental finding” [IF)]) as “a finding concerning an individual research participant that has potential health or reproductive importance and is discovered in the course of conducting research but is beyond the aims of the study. This means that IFs may be on variables not directly under study and may not be anticipated in the research protocol.”12 Interrogating this definition highlights four elements, which feature to a greater or lesser degree in other secondary finding definitions: (1) the relationship of the finding to research; (2) the relevance/importance of the information to research participants; (3) the foreseeability of the finding or a similar finding; and (4) the manner in which researchers obtained the information.

1.1.1 RELATIONSHIP OF THE FINDING TO RESEARCH AIMS

The most common element of secondary finding definitions are statements about the relationship between the finding and research aims. Definitions describe secondary findings as being “beyond the aims of the study,”13 outside “the original objectives of the research,”14 “coincidental to the primary goal of the relationship,”15 “not the intent of the study,”16 and “outside the scope of the research question.”17 Another variation questions whether researchers were “looking for” the information.18 While few explore these definitions more closely, Henry S. Richardson advocates interpreting “beyond the aims of the study” in “a way that makes room for the fact that scientific studies can, and frequently do, surprise or disappoint their designers.” 19 Richardson provides the example of a study of a proposed heart medication that unexpectedly finds that the drug enhances the erectile function of some participants. Since tracking the side effects of the medication falls within the study’s aims, this is not an “incidental” finding, despite the fact the researchers had not specifically aimed to find out anything about erectile dysfunction.20

1.1.2 RELEVANCE OF THE INFORMATION TO RESEARCH PARTICIPANTS

A number of definitions place parameters on the type of information that could comprise a secondary finding. The oft-cited definition from Wolf and others applies to findings of “potential health or reproductive importance.”21 Others limit secondary findings to information of importance to the participant’s health.22 Bartha M. Knoppers and Amy Dam go further still, suggesting that for information to comprise a secondary finding it must both be of health importance and meet the criteria of scientific validity and clinical utility.23

1.1.3 FORESEEABILITY

For some, secondary findings, by definition, involve a degree of unexpectedness, variously described as a requirement for the results to be “unanticipated,”24 “generated unexpectedly,”25 and “unforeseen by either party at the time of consent.”26 Wolf and colleagues take a more moderate approach, advising that secondary findings “may not be anticipated in the research protocol” without requiring non-anticipation as an element of their definition.27 On the other hand, Lisa Parker argues against the inclusion of an “unanticipated” element on the basis that “some research and clinical activities are so prone to generating findings not intentionally sought that it is disingenuous to term them ‘unanticipated’ even if their precise nature cannot be anticipated in advance.”28 She also notes that whether a result is “anticipated” depends on from whose perspective the question is considered. “From the perspective of investigators, the occurrence of [secondary findings] may be (indeed, should be) anticipated, but they are largely incidental or irrelevant to study aims. From the perspective of research subjects, the generation of an IF may be a startling occurrence that is far from an incidental or insignificant blip in their understanding of themselves and their health.”29

1.1.4 MANNER IN WHICH RESEARCHERS OBTAINED THE INFORMATION

A small number of definitions set constraints on the manner in which researchers obtained the information — namely, that the finding should have been obtained “in the course of conducting research.”30 Richardson explains that “if the design of a study calls for researchers to carry out certain procedures and if, by carrying out the procedures, they discover some information pertinent to the health of the study participants (or of their offspring, existent or potential), then that counts as a pretty clear case of a finding that arises in the course of conducting research.”31 However, he goes on to distinguish between a broad interpretation — results discovered during the time in which the research is ongoing — and a narrow interpretation (which he goes on to support) — results discovered by carrying out research procedures.

As an example of what might fall under the former, broader interpretation, we may think about what highly trained individuals may “find” on their way to work. One relatively well-studied example of this, which has been discussed under the rubric of “unsolicited medical advice,” is the case of what looks to a trained person to be a melanoma on the back of someone’s neck. The typical setting of this story in the literature so far is the bus stop. Let us change that. Suppose that, while escorting a research participant down the hall to the MRI machine, the researcher, who did a dermatology rotation in medical school, notices what looks to be a melanoma on the back of the participant’s neck. Does that count as an “incidental finding” in the intended sense?32

Richardson concludes that this does not count as an incidental finding. That is, that walking the participant down the hall is not a study procedure and the finding, therefore, is not one that arises “in the course of conducting research.”33

1.2 Analytic Validity

The accuracy of predictions about a genetic variant’s presence or absence in a research participant is at the heart of most definitions of analytic validity.34 Vardit Ravitsky and Benjamin S. Wilfond propose perhaps the most comprehensive definition in this regard, opining that “[a] result is analytically valid when it accurately and reliably identifies a particular genetic characteristic, such as a nucleotide sequence or a gene expression profile. Accuracy and reliability must be achieved both at the research stage of assay development and at the clinical application stage in which laboratory proficiency and quality control are required.”35 Ravitsky and Wilfond’s definition is broad enough to encompass the steps that Wolf and colleagues suggest to confirm a result’s analytic validity — namely, ensuring that the result is actually present, has been created properly, and belongs to a particular research participant.36 The definition put forward in 2006 by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Working Group on Reporting Genetic Results in Research Studies (2006 NHLBI Working Group) further specifies that “[a]nalytical validity requires analytical sensitivity (probability that a test will be positive when the genetic variant is present) and analytical specificity (probability that a test will be negative when the variant is absent).”37

Some commentators precondition analytic validity on more specific measures of accuracy. For Conrad V. Fernandez and Charles Weijer, a test’s analytic validity should be assessed by peer review.38 Annelien L. Bredenoord and her colleagues question whether peer review is sufficient to establish analytic validity, or if independent replication and peer review is needed.39 Others suggest the need to repeat the assay with a new sample and, ideally, a second test.40 Perhaps the greatest dispute when it comes to assessing analytic validity surrounds the need for the testing laboratory to be certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) Act of 1988. A number of commentators suggest that CLIA certification is an essential41 — or, at a minimum, desirable42 — element of analytic validity. However, critics dispute any necessary connection between CLIA certification and analytic validity.43 In developing updated disclosure guidelines in 2010, an NHLBI Working Group (2010 NHLBI Working Group) was unable to reach a consensus on the importance of CLIA certification as a measure of analytic validity.44

Finally, in several instances, discussions of analytic validity are intertwined with clinical validity or utility considerations. For example, Mildred Cho conceptualizes analytic and clinical validity as including “an evaluation of the strength of genotype-phenotype associations and predictive value.”45 Knoppers and Dam concurrently discuss “scientific validity” and “analytical utility,” defining them as “the accuracy by which the test predicts clinical outcome” or the “sufficient evidence to clinically validate the findings.”46 In contesting Ravitsky and Wilfond’s conception of analytic validity, Robert Klitzman argues that some results will be “neither clearly ‘analytically valid’ nor invalid, but of indeterminate validity” depending on their value in predicting disease progression or treatment outcomes. As discussed below, these are used more frequently (and arguably more correctly) as measures of clinical validity and clinical utility, respectively.47

1.3 Clinical Validity

Authors widely accept clinical validity as pertaining to the reliability or accuracy of a result in predicting a clinical outcome.48 The 2006 NHLBI Working Group looks to the “clinical performance” of a genetic test result “including its clinical sensitivity and specificity (as related to disease), and positive and negative predictive values.”49 Ravitsky and Wilfond describe clinical validity as referring to “the quality and quantity of empirical evidence regarding the association between a genotype and a particular clinical outcome, such as increased or reduced risk of a given condition.”50

Some go on to articulate the particular challenges that genetic research results pose for clinical validity. The 2006 NHLBI Working Group specifies that this would be “affected by the heterogeneity of the phenotypes, penetrance of the gene, bias in the study populations, and confounding of phenotypic modifiers.” 51 Others point to the iterative nature of scientific research,52 the often unclear functional relationship between genotype and phenotype,53 and the small number of studies on which estimates of validity may be based.54

While there is significant agreement that clinical validity pertains primarily to accurate and reliable predictions of clinical outcomes, several authors use the term in a way that explicitly or implicitly incorporates other common disclosure criteria. Some describe clinical validity in a manner more closely akin to clinical utility — that is, to pass judgment on the meaningfulness or value of study results.55 For example, Wolf and her colleagues link clinical validity to the “likely health or reproductive importance” of a finding.56 Other authors fail to clearly distinguish clinical validity from analytic validity.57

1.4 Clinical Utility, Significance, and Relevance

Clinical utility, clinical significance, and clinical relevance are three closely related terms frequently used in the secondary findings literature. These terms have broadly equivalent plain English meanings and, as evident from the discussion below, overlapping conceptualizations. Accordingly, we consider the terms under the one subheading to foster a closer appreciation of their considerable similarities and subtle differences.

1.4.1 CLINICAL UTILITY

The concept of clinical utility is subject to significant debate and divergent criteria for determination.58 Two main camps of clinical utility definitions are apparent: a basic and expanded version. The basic version focuses on the usefulness of the results for patient care. For example, Beskow and Burke define clinical utility in terms of the availability of a “proven therapeutic or preventive intervention,”59 criteria that also are adopted by Knoppers and Dam.60 The 2006 NHLBI Working Group refers to “the likelihood that the test will lead to an improved health outcome.”61 Annalien L. Bredenoord and her colleagues conceptualize clinical utility somewhat similarly, distinguishing between data of “immediate clinical utility” and that of “potential or moderate clinical utility.” The former is limited to data that entails “a significant health problem,” for which preventative or therapeutic measures are available. The latter encompasses, for example, “susceptibility loci associated with an elevated risk of having a disease, such as ischemic stroke, diabetes, or cancer or pharmacogenomics variants associated with adverse drug reactions.”62 They compare these with “data of personal or recreational significance.”63

In comparison, some scholars propose a more expansive version of clinical utility, which seeks to consider the value of the information to participants, above and beyond the potential for clinical intervention. In an early example of this conceptualization, Ravitsky and Wilfond argue that clinical utility should encompass three considerations: “the association between the result and the clinical condition (clinical validity), the likelihood of a clinically effective outcome, and the value of the outcome to the individual.”64 Wolf and her colleagues define “utility” to “include information that a research participant is likely to find important, even if clinicians cannot use that information to alter the participant’s clinical course.”65 They go on to “recognize a spectrum of utility to the participant, ranging from lifesaving to ameliorative to useful in heightening surveillance to useful in thinking and planning about health.”66 Notably, however, some scholars query the practical merit of such normative assessments — in particular, based on clinicians’ limited qualifications to make these determinations.67

1.4.2 CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE

Similarly to the basic version of clinical utility, most definitions of clinical significance link a secondary finding to the need for some form of clinical action. These include, for example, results that indicate the need for “follow-up clinical consultation,”68 the availability of preventative or treatment approaches,69 and results “requiring medical or surgical attention.”70 David I. Shalowitz and Franklin G. Miller adopt a somewhat expanded clinical significance definition to include those results that improve “treatment, prevention, or understanding of a disease” for a participant or their relatives.71 Isaac S. Kohane and Patrick L. Taylor approach “results significance” similarly to the expanded version of clinical utility put forward by others, explaining that it is inextricably intertwined with patient preferences since “personal views and values shape the benefits of even painful knowledge for a participant.”72

A smaller number of definitions link clinical significance to the mere presence or risk of a clinical condition. Knoppers and her colleagues recommend assessing clinical significance based on whether “identification of the variant permit[ted] an accurate prediction of the presence (or risk) of a clinical condition.” 73 In another article, Knoppers and Claude Laberge describe “adverse results, basic measurements (e.g., blood count, blood pressure) or critical values in lab tests” as “significant for participants.”74

1.4.3 CLINICAL RELEVANCE

While several definitions of clinical relevance bear close resemblance to clinical significance and utility, others are more closely akin to definitions of clinical validity. Illustrative of the former, Kohane and Taylor advise that clinical relevance requires distinguishing results from something “merely interesting or suggestive,” which may “require a clinician’s knowledge of the patient’s history, family, and environment.”75 Pullman and Hodgkinson agree that “[a]ll other things being equal, stronger associations are more likely to be clinically relevant.”76 They go on to note that “[t]he clinical relevance of a particular association for a specific patient additionally depends on the patient’s gender, age, medical history, and health behaviors.”77 Others distinguish between results such as monogenetic disease information that are “clearly clinically relevant” and “potentially relevant” information such as risk predictions.78 Based on FDA definitions in the context of biomarkers, clinical relevance also may connote “widespread agreement in the medical or scientific community about the significance of the results.”79

Some definitions of clinical relevance focus, instead, on the reliability or accuracy of a result in predicting a clinical outcome, reflecting definitions of clinical validity. For example, Regine Kollek and Imme Petersen identify “data of known individual and/or clinical relevance” based on “genetic mutations known to be causally involved in the development of cancer or other diseases.”80 Matthew Westbrook classifies a finding as “clinically relevant” if a genotype–phenotype association has been demonstrated to have a strong correlation in at least one study conducted with participants from that patient’s ancestral group.81 Another definition ties clinical relevance to the credibility of results, including credibility as influenced by the operating standards of responsible laboratories.82

1.4.4 OVERLAP BETWEEN CLINICAL UTILITY, CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE, AND CLINICAL RELEVANCE

Despite considerable similarities, and some divergence, in definitions proposed for clinical utility, clinical significance and clinical relevance, no article explicitly attempts to distinguish these terms. Fiona Miller and colleagues make the closest attempt at differentiation, contrasting results with “significant health implications” to research results that are “merely clinically relevant or useful,” suggesting that clinical significance may constitute a more stringent requirement than its counterparts.83 Some articles simply use the terms synonymously. For example, Knoppers and Dam use “clinical utility” and “clinical significance” to describe situations when “the use of the results leads to some improvement of outcome or the prevention of disease.”84 Other scholars have been prone to similar terminological conflation, including one of the authors of this paper, who in a recently published article, explained disclosure criteria for “clinical utility and severity” as “findings of genetic variants with known, urgent clinical significance.”85

1.5 Personal/General Utility

Authors typically invoke “personal utility” as a foil for clinical utility and related concepts in order to promote a patient-centered approach to decisions about disclosure of research findings.86 Paul Affleck, for example, opines that “to regard information as having value only in terms of its practical usefulness (and only its medical usefulness, at that) seems overly reductionist.” 87 Matthew Gordon, among others, critiques the narrow nature of clinical utility in terms of capturing the value of a research finding. Gordon notes that persons might find value in many actions beyond disease prevention, such as reproductive decision-making, contacting others for support, and monitoring information related to the disease to adopt any future preventive actions.88

While its dichotomy with clinical utility was broadly consistent, definitions of personal utility expressed quite different boundaries. Beskow and Burke conceptualize a spectrum of utility ranging from clinical utility (for which “a proven therapeutic or preventive intervention is available”), to personal utility (that may have benefits “for reproductive decision making or life planning”), to a far broader subset of information that “some individuals will find… useful in and of itself (e.g., through an enhanced sense of personal identity).”89 Other commentators include in “personal utility” results whose benefits extend well beyond reproductive decision-making and life planning. These include “verifiable results to which participants assign personal value,”90 results with “the potential to affect participants’ relationships or personal identity” included as related to ethnic or cultural identity and behavioral traits,91 and results with meaning for families and communities.92

1.6 Actionability

Definitions of actionability are grounded in the potential for knowledge of the incidental finding to lead to some kind of action. However, definitions are divided as to whether the relevant actions include treatment and prevention options as determined by clinicians, or a broader array of life-planning decisions as determined by the people to whom results relate. These conceptual divides mirror in many respects differences among definitions of clinical utility, and between definitions of clinical and personal utility.

In its narrow form, actionability is described on the basis of the availability of “effective treatment or prevention” options.93 As Sharon F. Terry distinguishes non-actionable from actionable results, “Findings might predict a condition, convey risk, diagnose a condition, and so on, but across the board, there is a high chance that there is no treatment based on these findings.”94 Other scholars adopt more participant-centered definitions of actionability. The 2010 NHLBI Working Group focuses on the health importance of disclosing incidental findings but also allow for health-promoting actions by research participants. Namely, they conceptualize actionability as the potential for an “improved health outcome,” but include, in addition to possible therapeutic or preventive interventions, “other available actions that may change the course of disease.”95 Wolf and colleagues refer with favor to the NHLBI Working Group’s definition but stress more directly the need to understand actionability from the participant’s perspective:

The core question is whether return of the [finding] offers the contributor and/or the contributor’s clinician the option to take action with significant potential to alter the onset or course of disease, such as by allowing heightened surveillance, preventive actions, early diagnosis, or treatment options. Although some commentators might understand actionability narrowly from the clinician’s perspective (can we prevent or cure?), we instead define actionability from the perspective of the individual facing the risk and potential disease (can I and/or my clinician take action to prevent or alter the course of my condition or to tailor my treatment?).96

Yet, even these definitions may be unduly narrow in light of public understandings of “actionability.” Members of the public from across the U.S. have suggested in focus group discussions that disclosure of research results could trigger actions as broad as “getting treatment or prevention, informing family members of risk, making reproductive decisions, working for environmental action or remediation, life and financial planning, and participating in further research.”97

1.7 Volition

A vexing issue as regards the return of incidental findings is finding ways to accommodate individual preferences whether to know about a genetic result (volition). Many papers take a policy stance on this issue, but few grapple seriously and meaningfully with definitional concerns — that is, what is meant by an individual “preference.” A common formulation appeals to the “expressed preferences of research subjects.”98 Lisa Parker further links participants’ “expressed preference” to their “choice or decision” to receive results.99 Franklin G. Miller and others formulate a similar question, being whether “a subject has explicitly indicated that she does not want to receive incidental findings.”100 A slightly different approach would charge researchers with asking participants about the kinds of results they would like to receive, without articulating details of a participant’s expected response. In this vein, Wolf and colleagues suggest that “researchers should try to find out whether participants would want to learn of a condition (or significant genetic risk of a condition) likely to be life-threatening that can (or cannot) be treated, a condition (or significant genetic risk of a condition) likely to be grave or serious that can (or cannot) be treated, or genetic information that can be used in reproductive decision-making to avoid or to ameliorate a life-threatening, grave, or serious condition in offspring.”101

Several papers also deal with the changeable nature of participants’ preferences, accepting that personal and familial circumstances will affect the results that participants want to know: “Reproductive planning, healthcare interactions, the diagnosis of oneself or someone in the family, deaths, and media reports about genetics, genomics and disease, are among the issues that could alter preferences as to receive research results and incidental findings.”102 To deal with participants’ future preferences, Matsui and his colleagues advise that “[i]n order to provide appropriate protection to the rights of the donors…a well-considered procedure for ascertaining and securing their preferences for future contact as well as future disclosure of the results must be planned at the very beginning of the research.”103 Kohane and Taylor further suggest the impossibility of understanding participant preferences without reference to results significance and, accordingly, the importance of effective communication between researcher and participant.104

Part 2: A Proposed Framework for Analyzing the Ethics of Disclosing Genetic Research Findings

In Part 1, we documented the diversity, inconsistency, and redundancy of terms and concepts appealed to in discussions of the ethics of disclosing findings in genetic research, and the potential implications of this definitional uncertainty for the development and implementation of disclosure frameworks. In this Part, we sketch an outline for a more cohesive and streamlined framework for analysis by identifying and describing the three core concepts that underlie all analyses of the ethics of disclosing secondary findings: (1) validity, (2) value, and (3) volition. We then demonstrate how each of the other concepts and terms that are frequently invoked in this debate fits within these three concepts as competing substantive interpretations of the more general concepts.

2.1 Developing an Overarching Framework for Disclosing Genetic Findings

This section outlines an overarching framework for assessing the ethics of disclosing genetic research findings. To do this, it asks several questions. First, what is the best way to delineate which kinds of results should or shouldn’t be captured by a comprehensive disclosure framework? In particular, what importance should attach to distinctions between primary and secondary research results? Beyond this threshold question, what concepts must be taken into account in assessing the ethics of disclosing findings and how do these concepts relate to current terminology in the disclosure literature? This is an ambitious task, and we do not purport to present a complete or final disclosure framework. Instead, we seek to provide sufficient building blocks to facilitate clear and conceptually sound analyses in the future.

Specifically, we suggest three concepts as the core considerations for analyzing the ethics of disclosing genetic findings: (1) validity, (2) value, and (3) volition. This tripartite framework (hereafter, the “3V framework”) reflects the general consensus that, at minimum, ethically responsible disclosure of genetic research findings requires that the findings be accurate and reliable, valuable in some way, and desired by (or desirable for) those with whom they will be shared. While these three concepts are present (explicitly or implicitly) in each of the articles analyzed here, the terminology used to describe them and understandings of their constituent parts differ markedly. To move beyond the resulting redundancy and confusion, our 3V framework employs new terminology for these concepts. We go on to make normative suggestions about what should be the content of these terms and concepts, with the goal of balancing benefits to participants through the disclosure of important information with the minimization of undue burdens on individual researchers and the research enterprise more generally.

2.1.1: DETERMINING “FINDINGS” FOR THE PURPOSE OF THE DISCLOSURE FRAMEWORK

As we discussed in Part 1, even the meaning of incidental or secondary finding is subject to significant definitional confusion. This disagreement is important because establishing whether a given piece of information counts as a secondary finding serves as a threshold question for most disclosure plans. A common presumption in drafting these plans is a normatively relevant distinction between “primary” research findings (which, provided they satisfy certain other conditions for disclosure, such as analytic and clinical validity, researchers are under an obligation to offer to return in most situations) and “secondary” research findings (which researchers might or might not be under an obligation to offer to return). Below, we analyze the various definitional elements ascribed to “secondary findings,” before discounting them as having ongoing relevance in the disclosure debate. Accordingly, we reject the distinction between primary and secondary findings, instead suggesting the application of our disclosure framework to “research findings” more generally.

The central distinction between primary and secondary research findings is their nexus with research aims and objectives. Primary findings have a direct nexus with the research enterprise; they will be intentionally sought and interpreted as part of the actions necessary to answer the research question. Secondary findings do not have this same clear nexus, and thus the lynchpin of most secondary findings definitions is a characterization of the finding’s relationship to research aims and objectives: that is, whether the results were “beyond the aims of the research,” or some variant thereof. While appeals to research aims and objectives are prima facie appealing as the basis for ethical distinctions, closer analysis suggests that as a definitional feature they are unduly malleable to support normative distinctions in disclosure requirements. This can be explored through two hypothetical case studies.

First, a genetic researcher is seeking to identify breast cancer-predisposition mutations and wants to sequence the BRCA regions in a population of minority women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. The narrow aim of the study is to identify novel mutations in this understudied population. With a scientific aim constructed narrowly like this, the researcher could plausibly claim that any discovery of already characterized BRCA variants would be irrelevant to the specific aims of the research, and thus should be viewed as secondary findings that do not need to be returned. Yet many will find her decision to disregard (and, consequently, fail to disclose) these results deeply disturbing, particularly given the clinical value of the information to participants. Clearly there can be cases where it seems right to return a given piece of information, but not because of its nexus with the research aims.

Compare this with a slightly different scenario in which a researcher’s scientific goals require analysis of five distinct genetic regions. Because of technological developments, WGS is cheaper and easier than sequencing the five regions of interest separately, so the researcher obtains WGS for participants but instructs the sequencing center to discard all of the genomic data except the five regions of interest for analysis. The discarded sequence information is likely to include at least some mutations of clinical value, but even though that information has been generated, the researcher will never have access to it. Here, our intuitions might run counter to those in the above case: even though information exists that might be clinically useful, the researcher does not have a duty to interrogate data completely unrelated to their research aim since using the most targeted means possible to obtain research findings is generally viewed as being ethically acceptable. Since a researcher is free to sequence just the five genetic regions in which she is interested, her selection of WGS as a cost-saving technological choice should not hold her hostage to additional and onerous analyses.

Our differing intuitive judgments about these scenarios suggest de-emphasizing whether research findings are within the aims or objectives of a research project, instead focusing on weighing the respective costs and benefits of finding the relevant information. In the first example, the researcher already must analyze the BRCA regions as a part of her research. Finding known BRCA mutations therefore imposes limited costs and has clear clinical value, so there may be sufficient grounds to disclose these findings independent of the information’s relationship to the scientific aims of the study. By contrast, a researcher has no research-related reason to “hunt” for findings nestled within WGS data that lie outside the domains necessary to meet research aims. At least at present, undertaking such a search has considerable costs that we may be unwilling to impose on the research enterprise in the absence of compelling reasons, including the financial and personnel costs of confirming and interpreting any finding.105 Even if we can be statistically confident that some clinically significant findings will go unreported, the burden on the research enterprise arguably outweighs the potential benefits. The work here involves weighing the costs and benefits of obtaining findings; nexus with specific aims is not a useful distinction (except perhaps as a proxy for whether the information is already at hand, thus mitigating the burden of obtaining it).

Two other elements are used in the literature to limit the ambit of secondary research findings that may be subject to disclosure obligations: the relevance of the information to research participants (for example, findings of potential health or reproductive importance) and the ability (or lack thereof ) to anticipate a finding’s appearance. In our view, neither of these serves an ongoing role in determining disclosure requirements. The relevance of the information to research participants (for example, information “of potential health or reproductive importance”) is — at best — an unnecessary definitional element given other conditions for the disclosure of genetic research findings. At worst, it is directly contradictory. Consider a model that requires the disclosure of research findings with “clinical utility.” Here, limiting research findings to information of health or reproductive importance is redundant: the clinical utility requirement is doing broadly the same work but likely in a more targeted and nuanced manner. Another model may require disclosure in a broader subset of circumstances, including results that are expected to have “personal utility” for participants. In this context, limiting research findings to information of health or reproductive importance would be antithetical. While we appreciate the importance of limiting disclosure to findings that meet baseline standards of materiality and relevance, this work is better handled by transparent and flexible substantive disclosure criteria. Additionally, the requirement for secondary findings to be “unforeseeable” or “unanticipated” is outdated in an era of WGS. As Lisa Parker explains, some research activities, such as WGS, are so prone to generating unintentional findings that terming them “unanticipated” is disingenuous. Other specific findings, such as non-paternity, are common and recurrent. We consider these distinctions extraneous to normative analyses regarding the disclosure of genetic research findings.

Accordingly, we dispute an ongoing role for distinguishing between “primary” and “secondary” research findings to determine disclosure obligations. Instead, the key question is whether the finding is a “research finding” — that is, whether it is a new piece of information that relates to a particular individual discovered by virtue of research procedures106 — and, if so, whether it meets the substantive disclosure requirements of value, validity, and volition.107 This conclusion is consistent with Erik Parens and colleagues’ recent statement in the Hastings Center Report that “once researchers are aware of having readily identifiable, clinically significant findings, how they get there is not material to the question of their disposition.”108

2.1.2 DETERMINING VALIDITY

The first core concept appealed to in all discussions regarding the ethical return of research findings is validity. At its core, validity is a purely descriptive property regarding the scientific quality of a research finding. A finding is valid, then, when it accurately, precisely, and reliably represents or describes material phenomena in scientific explanations or predictions, even if such explanations or predictions lack significance or value for anyone.

Validity constitutes a necessary but insufficient scientific bar that genetic findings must satisfy in order to qualify for disclosure. In the context of genetic findings, the literature converges around definitions of analytic validity as relating to the accuracy of predictions about a genetic variant’s presence or absence in a research participant. Additionally, most scholars define clinical validity in terms of the reliability or accuracy of a result in predicting a clinical outcome. While understandings of these components of validity are relatively straightforward, those developing disclosure models will benefit by addressing two sources of discord. First, how should one prove validity when it comes to genetic test results? In particular, what meaning and weight should be attached to compliance of the testing laboratory with the Clinical Laboratory Improvements Amendments (CLIA) of 1988? Secondly, should the meaningfulness of genetic findings be included as a component of clinical validity?

In answer to the first of these questions, given CLIA’s limitations when it comes to genetic test results, preconditioning a finding’s analytic validity (as compared with the legality of its disclosure) on CLIA accreditation or certification seems unwarranted. While CLIA compliance involves some relevant requirements, these are neither necessary nor sufficient to support a claim of analytic validity. Further, we advise against incorporating the meaningfulness of study results into definitions of clinical validity — for example, a finding’s likely health or reproductive importance. Instead, clinical validity determinations should be limited to the goal of ascertaining the empirical evidence linking a genomic result to a clinical outcome. Despite some practical challenges (e.g., phenotypic heterogeneity, incomplete penetrance, and a limited scientific evidence-base), this retains clinical validity as an objective, empirically grounded determination. In comparison, clinical value judgments require subjective assessments, the answers to which often depend on the characteristics of individual participants such as age and co-morbidities. These judgments are conceptually and practically distinct. An objective definition retains clinical validity as a necessary but insufficient scientific bar that secondary findings must meet, before addressing the more subjective and participant-specific considerations that go into clinical value.

Finally, some conceptions of validity fail to distinguish clearly between analytic and clinical validity and, hence, fail properly to appreciate the important and unique function served by each type. Sometimes this results from definitions that purposefully combine the terms, at other times from definitions that refer expressly to analytic validity but adopt aspects of clinical validity such as clinical outcome and disease progression. Such terminological conflation may result in confusion and, consequently, improper disclosures. There is clearly a difference between (1) accurately and reliably identifying the presence of a genetic variant in a person and (2) accurately and reliably predicting a clinical outcome associated with that variant. This difference warrants maintaining a distinction between analytic and clinical validity and viewing them as discrete and necessary conditions of any conception of validity. Combining the terms or confounding their meaning risks the disclosure of findings that meet one of these conditions but not the other.

2.1.3 DETERMINING VALUE

The second core concept appealed to in all discussions regarding the ethical return of research findings is value. At its core, value is a normative property regarding the worth, significance, or utility of a research finding (whether subjective or objective). A finding has value, then, to the degree that it is necessary for or contributes to a state of affairs that has worth, significance, or utility.

Determining the requisite value of a research finding so as to compel (or permit) disclosure is likely the most terminologically and conceptually vexed issue in developing disclosure models. A wealth of terms, many duplicative and overlapping, has accrued to describe the value that a finding may have for a participant, including clinical utility, clinical significance, clinical relevance, actionability, personal utility, and many more. Minimizing this terminological confusion and redundancy is a first step towards the development of a cohesive disclosure framework in the future. In particular, this may promote harmonization between models where this is a relevant goal and, where variation between disclosure models is warranted, may permit better articulation of the relevant differences between them.

2.1.3.1 Necessary Concepts to Articulate Comprehensive Value Conceptions

Two preliminary questions must be answered in order to move beyond current terminological confusion and redundancy: What are the key value concepts that warrant consideration in models for disclosing genetic research findings? To what extent are terms in current usage congruent with these value concepts? Below we suggest four distinct kinds of value that are necessary to conceptualize the value of disclosing genetic research findings. We go on to show widespread inconsistency in the value concepts encompassed by terms currently adopted in the literature.

-

Direct clinical value: The capacity to prevent, ameliorate, or cure the onset of disease is perhaps the clearest kind of value a participant may gain from the disclosure of genetic research findings. Findings of this kind can be conceptualized as having “direct clinical value.” Breaking this down further, we understand “direct” value as involving a straight causal link between disclosure of the finding, a tangible clinical action, and an outcome for the individual to whom the genomic sequence relates. For “clinical,” at least as a preliminary marker, we adopt a plain English meaning: “relating to the bedside of a patient or to the course of his disease; denoting the symptoms and course of a disease, as distinguished from the laboratory findings of anatomical change”109 Diagrammatically, direct clinical impact can be depicted as follows:

research finding→ clinical action→ valuable clinical outcome

-

Indirect clinical value: Disclosing genetic research findings may give the participant knowledge with clinical value for the participant or another, but without a clear avenue for the participant to take clinical actions that directly benefit him or herself. Instead, disclosure may have value because it enhances participants’ disease understanding or reduces future diagnostic odysseys. Genetic research findings that enhance participants’ reproductive decision-making also could fall within this category by enabling a valuable clinical outcome for another — here, an unborn future child. Finally, knowledge could have clinical value by prompting information sharing between a participant and a person for whom clinical actions are available (e.g., child, sibling, parent). This “indirect clinical value” can be depicted as follows:

research finding→ participant knowledge→ (1) valuable clinical understanding for participant; and/or (2) valuable clinical outcome for a related third party

-

Direct non-clinical value: Outside the clinical domain, genetic research findings may have directly beneficial outcomes for participants. For example, disclosure may provide participants with the opportunity to purchase life and long-term care insurance, lobby for political action, and inform family members. While these outcomes may have positive flow-on health effects, the actions themselves do not fit within the “clinical” realm as defined above. This “direct non-clinical value” can be depicted as follows:

research finding→ non-clinical action→ valuable non-clinical outcome

-

Indirect non-clinical value: Participants may value genetic findings for intrinsic (as compared with clinical) reasons, divorced from any available clinical or personal actions. For example, disclosure may provide participants with knowledge of misattributed paternity or greater understanding of their ethnic, cultural, and/or personal identity and heritage. “Indirect non-clinical value” can be depicted as follows:

research finding→ participant knowledge → valuable non-clinical understanding

Notably, a given genetic research finding may satisfy multiple value categories. For example, a finding revealing a predisposition to Huntington’s disease may satisfy the requirements for direct non-clinical value by enabling a participant to buy long-term care insurance, participate in clinical trials, and otherwise lobby for political change. Depending on a participant’s age and other characteristics, disclosure also might provide indirect clinical value, for example, by enabling reproductive decision-making.

2.1.3.2 Currently Available Terms for Articulating These Value Concepts

There is no commonly understood means of distinguishing between these kinds of value in the current literature. Rather, given conceptions of value are associated with multiple terms, and vice versa, leading to redundancy and confusion.

Most clearly in this regard, our literature review shows broad similarities in how the terms “clinical relevance,” “clinical utility,” and “clinical significance” are being conceptualized. Given the terms’ similar plain English meanings, slippage between the terms is likely to remain an ongoing problem regardless of any scholarly attempts to draw meaningful distinctions. Our analysis also shows close parallels between “actionability” and definitions of clinical and personal utility, suggesting further terminological redundancy.

In sum, terminological variation within, and slippage between, current terms and concepts of value are impeding the development of well-conceived and consistent models for disclosing genetic research findings.

2.1.3.3 A Consolidated Terminological Framework

Given current terminological confusion and inconsistency, we suggest consolidating and harmonizing the terms and concepts used to assess the value of genetic research findings. This begins with the core concept of value itself. Unlike “utility,” which implicitly privileges the purely instrumental value that disclosure of findings might have, “value” can encompass both instrumental and intrinsic considerations. From there, findings can be distinguished according to whether they have direct clinical value, indirect clinical value, direct non-clinical value, and/or indirect non-clinical value.

This raises the question of which kinds of value are sufficient to ground a duty of disclosure, along with the requisite magnitude of any such value. Putting forward a definitive view on this issue is beyond the scope of this paper and may differ depending on a range of factors such as the participant group, research project at issue, and other considerations. Yet our proposed value concepts appear to fall along a spectrum when it comes to determining disclosure duties, with direct clinical value (#1) being the most likely to garner support for a duty to disclose, followed by indirect clinical value (#2), direct non-clinical value (#3) and, finally, indirect non-clinical value (#4). While commentators no doubt will differ on the appropriate place to draw a line, we tend to believe that this will fall somewhere between #2 and #3. In our view, maximizing disclosures that promote clinical benefits, without requiring disclosures valued because of their non-clinical outcomes, provides appropriate benefits to participants while minimizing undue burdens on researchers and the research enterprise.

2.1.4 DETERMINING VOLITION

The third core concept appealed to in discussions regarding the ethical return of research findings is volition, which the Medical Dictionary defines as “an act of making a choice or decision.”120 Unlike validity and value, then, volition focuses less on the newly discovered information itself and more on the person to whom disclosure is being considered. Specifically, it pertains to whether and by what process a research participant or specimen donor was sufficiently informed about the possibility of return of results and given an opportunity to consent to their disclosure. The concept of volition, connected as it is with a person’s will, choices, desires, or preferences, has both descriptive and normative dimensions. On the one hand, there is the simple psychological matter of whether and in what ways and to what degree someone desires the disclosure of a research result, as well as the practical matter of how best to determine this. On the other hand, there is also a sense that such desires or preferences are intimately connected with values and norms. Volition conveys what a person values (at least at a certain time and with certain information at hand), and this is usually thought to carry some moral weight. It is something that at least should be accounted for, if not deferred to, when decisions are made and policies are developed.

As was the case with the previous two core concepts, there are potentially numerous competing conceptions of volition. Different conceptions of volition may require different kinds or levels of “informedness” and stability. They may also differ with respect to what they regard as “defeaters” of volition (e.g., coercion, deception, manipulation, misunderstanding, instability/inconsistency, and so on) that nullify the moral weight that acts of volition might otherwise carry. Most obviously, different conceptions of volition will differently evaluate its moral significance. On some conceptions, a person’s clear and informed decision regarding disclosure will be ethically sufficient to require researchers to respect that decision (regardless of the content of the decision for or against disclosure); on other conceptions, volition alone will not settle the ethical questions, but will need to be supplemented with additional considerations, like validity and value.

Further work is needed in understanding participant preferences (volition) to receive genetic research results and how this should be handled in disclosure models.121 Several important questions lie at the center of this issue. First, is volition always necessary as a feature of disclosure models? Most models to date have assumed this to be the case; however, the ACMG Recommendations indicate that — at least for a highly specific list of mutations in the clinical context — testing laboratories may be obliged to disclose the results at least as far as to the ordering physician.122 Secondly, assuming that some degree of volition is in fact necessary, how should it be conceptualized given the changeable nature of participants’ preferences and the challenges of knowing in advance the range of information that researchers may find? Finally, is volition sufficient to determine ethical permissions or obligations of any kind with respect to the disclosure of genetic research findings?

While our concern in this paper is primarily to establish a general framework and not to take more substantive positions about the three concepts, we suggest some initial inclinations. In our view, volition serves an ethical “gate-keeping” role in disclosure decisions. In other words, once a piece of information is accepted as a “research finding,” the first substantive criterion that must be looked to is volition. Usually, a person’s decision not to receive research findings should be respected, regardless of a finding’s validity and value. However, a person’s preference to receive findings is not, by itself, sufficient to make disclosure obligatory. Instead, it opens the gate, so to speak, to examine further criteria, such as validity and value. If a desired result is both valid and sufficiently valuable, then disclosing it would be morally permissible and, perhaps, morally obligatory.

Volition is a heated and rapidly advancing issue in the field that warrants dedicated consideration in future research. The questions it raises, especially concerning the normative significance of an individual’s desires or preferences, are difficult, but important matters for the future of genetic research ethics.

Conclusion

The secondary findings issue has generated an impressive body of literature over the past decade. It is remarkable that, despite this sustained academic and policy attention, we do not seem to be approaching consensus. Seemingly intractable problems remain unsolved, and new ones are arising to make the landscape even more complicated. Nevertheless, we believe that it is time for the debate to move forward. Our analysis suggests that the research and bioethics communities may actually agree on more than it seems, but that further progress is limited by the literature’s terminological confusion. The 3V framework provides the conceptual building blocks that can facilitate a more fruitful debate. If everyone uses the same conceptual apparatus and language, we can more readily identify the shared concepts that we agree upon, thus isolating and focusing in on how to reconcile the values and assumptions inherent in our differing conceptions of validity, value, and volition.

Figure 1.

The “3V” Framework for Analyzing the Ethics of Disclosing Secondary Findings. As a threshold requirement to fall within the scope of a disclosure framework, information must constitute a “research finding.” To meet the substantive requirements to qualify for disclosure, research findings must meet the requisite requirements of validity, value, and volition.

Table 1.

Currently Available Terms for Articulating Value Concepts

| Term | Value Concept | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical utility | Direct clinical value | The availability of a proven therapeutic or preventive intervention.110 |

| Clinical utility | Direct clinical value plus some measure of the other kinds of value | Consider clinical validity, the likelihood of a clinically effective outcome, and the value of the outcome to the individual.111 |

| Clinical significance | Direct clinical value | Results that indicate the need for follow-up clinical consultation;112 results requiring medical or surgical attention.113 |

| Clinical significance | Direct and indirect clinical value | Whether identification of the variant permits an accurate prediction of the presence (or risk) of a clinical condition.114 |

| Actionability | Direct clinical value | The availability of effective treatment or prevention options;115 the potential for an improved health outcome.116 |

| Actionability | Direct clinical value and direct non-clinical value | Getting treatment or prevention, informing family members of risk, making reproductive decisions, working for environmental action or remediation, life and financial planning, and participating in further research.117 |

| Personal utility | Direct non-clinical value | Information that may have benefits for reproductive decision making or life planning.118 |

| Personal utility | Direct and indirect nonclinical value | Verifiable results to which participants assign personal value.119 |

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the insightful comments provided by Dr. John Lantos, Dr. Scott Kim, and faculty and fellows of the NIH Department of Bioethics.

Biographies

Lisa Eckstein, S.J.D., is a lecturer in law and medicine in the Faculty of Law at the University of Tasmania. While this article was written, she was a post-doctoral fellow in the NIH Department of Bioethics. Dr. Eckstein earned a Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) from the Georgetown University Law Center in 2012. Her previous studies were in Sydney, Australia where she completed a Master of Health Law (University of Sydney, 2010), and a bachelor’s degree in law and genetics (University of New South Wales, 2003).

Jeremy R. Garrett, Ph.D., is a Research Associate in Bioethics at the Children’s Mercy Bioethics Center at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Missouri and an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. He holds a Ph.D. in Philosophy from Rice University. His work on this article and other projects related to the ethics of returning individual research results is supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute (#R21HG006613).

Benjamin E. Berkman, J.D., M.P.H., is a faculty member in the NIH Department of Bioethics and is the Deputy Director of the Bioethics Core at the National Human Genome Research Institute. Mr. Berkman received a bachelor’s degree in the history of science and medicine at Harvard University (1999). He subsequently earned a Juris Doctor and a Master of Public Health from the University of Michigan (2005).

Footnotes

The opinions expressed are the authors’ and do not reflect the positions of the National Institutes of Health, the U.S. Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

References

- 1.For a discussion of these ethical principles and their implications for disclosure obligations, see Bredenoord AL, et al. Disclosure of Individual Genetic Data to Research Participants: The Debate Reconsidered. Trends in Genetics. 2011;27(2):41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.11.004.Bredenoord AL, Onland-Moret NC, Van Delden JJ. Feedback of Individual Genetic Results to Research Participants: In Favor of a Qualified Disclosure Policy. Human Mutation. 2011;32(8):861–867. doi: 10.1002/humu.21518.

- 2.Kollek R, Petersen I. Disclosure of Individual Research Results in Clinico-Genomic Trials: Challenges, Classification and Criteria for Decision-Making. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2011;37(5):271–275. doi: 10.1136/jme.2009.034041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dressler LG, Smolek S, Ponsaran R, Markey JM, Starks H, Gerson N, Lewis S, et al. IRB Perspectives on the Return of Individual Results from Genomic Research. Genetics in Medicine. 2012;14(2):215–222. 220. doi: 10.1038/gim.2011.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green RC, Berg JS, Grody WW, Kalia SS, Korf BR, Martin CL, McGuire AL, et al. ACMG Recommendations for Reporting of Incidental Findings in Clinical Exome and Genome Sequencing. Genetics in Medicine. 2013;15(7):565–574. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burke W, Matheny Antommaria HAH, Bennett R, Botkin J, Wright Clayton E, Henderson GE, Holm IA, et al. Recommendations for Returning Genomic Incidental Findings? We Need to Talk! Genetics in Medicine. 2013;15(11):854–859. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues. Anticipate and Communicate: Ethical Management of Incidental and Secondary Findings. [last visited April 10, 2014];Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues. 2013 Dec; doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu217. available at < http://bioethics.gov/sites/default/files/FINALAnticipate-Communicate_PCSBI_0.pdf>. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Id., at 28–29.

- 8.This distinction is frequently traced back to Gallie’s discussion of “essentially contested concepts” and to Rawls’ elaboration of related issues in A Theory of JusticeGallie WB. Essentially Contested Concepts. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society. 1956;56:167–198.Rawls J. A Theory of Justice. Chap 32 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press;

- 9.A list of these journal articles is available from the authors on request.

- 10.Christenhusz GM, Devriendt K, Dierickx K. Secondary Variants – in Defense of a More Fitting Term in the Incidental Findings Debate. European Journal of Human Genetics. 2013;21(12):1331–1334. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tabor HK, Berkman BE, Chandros Hull S, Bamshad MJ. Genomics Really Gets Personal: How Exome and Whole Genome Sequencing Challenge the Ethical Framework of Human Genetics Research. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2011;155:2916–2924. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolf SM, Lawrenz FP, Nelson CA, Kahn JP, Cho MK, Wright Clayton E, Fletcher JG, et al. Managing Incidental Findings in Human Subjects Research: Analysis and Recommendations. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):219–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00266.x.. For examples of uptake, see Richardson HS. Incidental Findings and Ancillary-Care Obligations. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):256–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00268.x.Simon CM, Williams JK, Shinkunas L, Brandt D, Daack-Hirsch S, Driessnack M. Informed Consent and Genomic Incidental Findings: IRB Chair Perspectives. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics: An International Journal. 2011;6(4):53–67. doi: 10.1525/jer.2011.6.4.53.Van Ness B. Genomic Research and Incidental Findings. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):292–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00272.x.

- 13.Wolf SM, Crock BN, Van Ness B, Lawrenz F, Kahn JP, Beskow LM, Cho MK, et al. Managing Incidental Findings and Research Results in Genomic Research Involving Biobanks and Archived Data Sets. Genetics in Medicine. 2012;14:361–384. 364. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.23.Wolf SM. Introduction: The Challenge of Incidental Findings. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):216–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00265.x.; see Wolf et al., supra note 12; Richardson, supra note 12, at 258. See also Parker LS. Best Laid Plans for Offering Results Go Awry. American Journal of Bioethics. 2006;6(6):22–23. doi: 10.1080/15265160600934913.(“Restricted by the study’s hypothesis or research question.”)

- 14.Knoppers BM, Dam A. Return of Results: Towards a Lexicon? Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2011;39(4):577–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller FG, Mello MM, Joffe S. Incidental Findings in Human Subjects Research: What Do Investigators Owe Research Participants? Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):271–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00269.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terry SF. The Tension Between Policy and Practice in Returning Research Results and Incidental Findings in Genomic Biobank Research. Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology. 2012;13:691–925. 705. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.2117289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho MK. Understanding Incidental Findings in the Context of Genetics and Genomics. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):280–285. 281. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00270.x.. See also Kohane IS, Taylor PL. Multidimensional Results Reporting to Participants in Genomic Studies: Getting It Right. Science Translational Medicine. 2010;2(37):37cm19, 2. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000809.

- 18.Hens K, Nys H, Cassiman JJ, Dierickx K. The Return of Individual Research Findings in Paediatric Genetic Research. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2011;37(3):179–183. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.037473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Knoppers BM, Rioux A, Zawati MH. Pediatric Research ‘Personalized’? International Perspectives on the Return of Results. Personalized Medicine. 2013;10(1):89–95. doi: 10.2217/pme.12.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.See Richardson, supra note 12, at 258.

- 20.Id.

- 21.See Wolf et al., supra note 12. Equivalent constraints are included in Wolf, supra note 13.

- 22.See Knoppers and Dam, supra note 14, at 580; Miller, Mello, and Joffe, supra note 15; Knoppers, Rioux, and Zawati, supra note 18.

- 23.See Knoppers and Dam, supra note 14, at 580.

- 24.See Kohane and Taylor, supra note 17, at 2.

- 25.See Wolf, supra note 13, at 216.

- 26.See Knoppers and Dam, supra note 14, at 580.

- 27.See Wolf et al., supra note 12. Emphasis added.

- 28.Parker LS. The Future of Incidental Findings: Should They Be Viewed as Benefits? Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics. 2008;36(2):341–351. 341. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2008.00278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Id., at 342.

- 30.See Wolf et al., supra note 12; Wolf, supra note 13, at 216.

- 31.See Richardson, supra note 12, at 258.

- 32.Id.

- 33.Id.