Abstract

Allowing long-term care (LTC) residents to make choices about their daily life activities is a central tenet of resident-centered care. This study examined whether staff and family rated care episodes involving choice differently from care episodes not involving choice. Seventeen nurse aide and15 family participants were shown paired video vignettes of care interactions. Participants were asked to rate their preferred care vignette using a standardized forced-choice questionnaire. Focus groups were held separately for staff and family members following this rating task to determine reasons for their preferences. Both staff and family rated the vignettes depicting choice as “strongly” preferred to the vignettes without choice. Reasons provided for the preference ratings during the focus group discussions related to resident well-being, sense of control, and respondents’ own personal values. These findings have implications for LTC staff training related to resident-centered care to promote choice.

Keywords: quality of care, culture change, resident choice, nursing home, consumer preferences

Introduction

Allowing long-term care (LTC) residents to make choices about their daily life activities is a central tenet of resident-centered care and offers the opportunity for both cognitive stimulation and social engagement (Bowers, Nolet, Roberts & Esmond, 2007). Indeed, beyond its intuitive appeal, the importance of choice is supported by research evidence showing a link between older adults’ sense of control over aspects of their daily lives and their quality of life (King, Yourman, Ahalt, Eng, Knight, Perez-Stable & Smith, 2012). In addition, a separate recent study showed a relationship between older adults’ sense of control and their cognitive functioning. This study also demonstrated that one’s sense of control can fluctuate from day to day and even within the same day (Neupert & Allaire, 2012). Thus, the rationale for LTC staff to offer residents choices about multiple aspects of their daily life throughout the day appears to be supported by growing research evidence.

Consistent with these findings, both LTC residents and staff have self-reported via interviews that they value resident choice and control over their everyday lives (Doty, Koren & Sturla, 2007; Kane, Caplan, Urv-Wong, Freeman, Aroskar & Finch, 1997). However, nurse aide staff also have acknowledged that it is often difficult for them to provide residents with choice and control due to routinized care schedules and other aspects of the LTC environment that emphasize resident safety over choice (Kane et al., 1997). Similarly, staff have admitted to minimizing their interactions with residents due to concerns about time and the need to complete assigned work tasks (Bowers, Lauring & Jacobson, 2001). Finally, missed care occurrences and routine shortcuts have been reported as common due to staffing limitations and workload burden (Kalisch, 2006; Lopez, 2006; Schnelle, Simmons, Harrington, Cadogan, Garcia, & Bates-Jensen, 2004; Simmons, Durkin, Rahman, Choi, Beuscher & Schnelle, 2012).

Staff time constraints and competing work demands may be, at least partially, why the results of multiple studies using diverse methodologies to document staff-resident care interactions have shown that LTC residents are seldom encouraged by staff to make decisions about basic aspects of their daily life including when to get out of bed, what to wear, and when and where to dine (Boscart, 2009; Christenson, Buchanan, Houlihan & Wanzek, 2011; Schnelle, Bertrand, Hurd, White, Squires, Feuerberg, Hickey & Simmons, 2009; Simmons, Rahman, Beuscher, Jani, Durkin & Schnelle, 2011; Simmons, et al., 2012). The results of two recent observational studies revealed that the most typical staff-resident interaction either showed a lack of any communication at all during care provision or was characterized by a staff statement that oriented the resident to the care being provided but did not offer any choice (Schnelle et al., 2009; Simmons et al., 2011). Another observational study showed that nurse aide staff often delayed care provision – including any interaction with residents - for long periods of time due to resident care burden and workload, which resulted in residents being given no opportunity for choice at all for some aspects of care (Simmons et al., 2012).

These findings highlight the discrepancy between staff self-reports that they value choice as important and LTC practice wherein staff often do not foster resident choice during daily care provision. Beyond concerns about time, there may be other reasons for this discrepancy. First, it is possible that, despite the growing emphasis in federal regulations on resident-centered care and the provision of choice (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2009), there is some confusion about how these relatively abstract concepts translate into daily care practice at the nurse aide level, especially when many LTC residents have cognitive impairment, hearing impairment and other limitations that can make staff-resident communication challenging. Second, a recent review article posits that our assumptions about the importance of choice for autonomy and well-being are largely based on the perspective of educated, affluent Westerners and, thus, may not be generalizable to other cultures or even Western working-class individuals. In fact, the provision of choice can be viewed as excessive and have unintended negative consequences in certain social and cultural contexts (Markus & Schwartz, 2010). Thus, it is possible that the direct care workforce in LTC, which is often comprised of lower-income minority individuals, may not actually value choice in a manner consistent with resident-centered care. Finally, as mentioned previously, nurse aides may not feel that they are able to offer residents choices due to a restrictive LTC environment that is based on staffing schedules, care routines, regulations and safety issues (Bowers, Lauring & Jacobson, 2001; Kane et al., 1997; Lopez, 2006).

The purpose of this study was to determine how front-line staff responsible for direct care (nurse aides) and family members of residents recognized and valued staff provision of choice when specific care scenarios were shown to each group via video vignettes. This study was conducted as part of a larger intervention study designed to train nurse aides in how to offer residents more choice during daily care provision to enhance resident-centered care practices. Based on various reports that choice is valued by multiple LTC stakeholder groups (CMS, 2009; Bowers, Nolet, Roberts & Esmond, 2007; Doty, Koren & Sturla, 2007; Kane, et al., 1997), it was hypothesized that both nurse aides and family members would rate staff-resident interactions in which choice was offered to residents as preferable, which would further support current LTC efforts to provide resident-centered care and increase residents’ choice and autonomy (CMS, 2009). However, we also expected family ratings would reflect stronger preferences for choice relative to staff due to potential concerns about time and other work environment constraints (REFs) as well as the potential for bias due to race or socioeconomic status (Markus & Schwartz, 2010).

Thus, to augment the quantitative ratings, focus groups were held separately with each group to discuss the reasons for their ratings and identify if there were instances during which staff felt they were unable to offer choice and/or families felt it was understandable that choice could not be offered to better understand potential discrepancies between self-reported value and actual staff behavior in daily care practice. The intent was for these data to inform the larger intervention trial to train nurse aides in how to allow residents more choice during morning care practice. To date, previous studies have not directly asked nurse aides or residents’ families to rate the quality of realistic staff-resident interactions that differ on this key aspect of care - whether residents are offered a choice – and subsequently asked both groups to explain the reasons for their ratings. This study addressed the following research questions:

Do nurse aides and family members rate video vignettes in which residents are offered choice as more preferable than vignettes in which residents are not offered choice for specific aspects of morning care?

What qualitative reasons do these two LTC stakeholder groups provide for their quantitative ratings related to choice?

Methods

Subjects and Setting

Participants were recruited from two community, for-profit LTC facilities housing a total of 312 residents (average occupancy rate = 93%) and one Veterans Administration facility housing 122 residents (occupancy rate = 87%) at the time of the study. Due to recent culture change initiatives in both community (CMS, 2009) and VA LTC facilities (Kheirbek, n.d.), upper-level administrative staff in each of the three sites reported that staff had received in-service training related to resident-centered care. The two community facilities were participants in a larger intervention trial designed to train LTC staff in how to allow residents choice during morning care provision.

The structured questionnaire and the focus group sessions related to choice were both conducted prior to data collection for the larger intervention trial to avoid contamination of staff or family responses. The primary reason for not including residents in this study was due to the inclusion criteria for the larger intervention trial which required residents to be long-stay, dependent on staff for one or more aspects of morning care and able to respond to simple questions about their daily care preferences. These inclusion criteria resulted in a resident sample likely to be too cognitively impaired for the questionnaire and focus group data collection in this study. Thus, in lieu of the residents themselves, family members were included in addition to LTC staff to represent two distinct LTC stakeholder groups for resident-centered care.

Thirty-two participants were recruited for five focus groups (two groups of nurse aide staff and three groups of family members) across the three participating facilities. Nurse aides (n=17) were recruited through flyers posted in employee break rooms and a brief description of the study presented at regularly-scheduled employee meetings. Family members (n=15) were recruited through flyers posted at the front desk of each facility, a mailed announcement, and a brief description of the study presented at regularly-scheduled family support group meetings. The only inclusion criteria was that nurse aides be currently employed at one of the three participating facilities and that family members have a relative currently or recently residing in one of these LTC facilities. Individual participation was voluntary, and written informed consent was required prior to participation. To facilitate open discussion, facility supervisors (licensed nurses) were not present during the nurse aide focus groups and no facility staff was present during the family focus groups. The university-affiliated Institutional Review Board approved the recruitment and consent procedures for this study. Each participant (staff and family) received $20 for their participation.

All participating nurse aides were African-American and female. These demographic characteristics closely mirrored the gender and ethic mix of nurse aide staff at the participating facilities. No other demographic information was obtained for nurse aide participants. Family participants were 87.7% female and 73.7% Caucasian (26.7% African American). The mean age of the family participants was 61 (±14) years and the average length of stay for their relative in the facility was 3 (±1.5) years. Nearly half of the family participants (46.7%) reported visiting their relative daily or almost daily. Approximately three-quarters (73.3%) had been caregivers for their relative prior to nursing home placement for an average of 4 (±3) years. Approximately half of the family participants were either a spouse (26.7%) or an adult child (26.7%) of the resident, with an additional 47.3% related in some other way (e.g., niece).

Quantitative Evaluation

Participants were shown a total of 12 brief video vignettes in pairs (average length: 22 seconds per pair), with each pair depicting a different aspect of morning care. Specifically, the following aspects of morning care provision were illustrated in the vignettes: (Pair 1) time to get out of bed; (Pair 2) assistance to use the toilet; (Pair 3) when to get dressed; (Pair 4) what to wear when getting dressed; (Pair 5) where to have breakfast; and (Pair 6) time to get out of bed when two staff are required for resident transfer. Two different scenarios were depicted related to “time to get out of bed” – one in which only one staff member was necessary (Pair 1) and a separate scenario in which two staff members were necessary (Pair 6). The rationale here was that some LTC residents require assistance from two staff members to transfer out of bed, and it was hypothesized that providing residents a choice would be rated lower by nurse aides in the second scenario, due to the need for additional staff coordination of care (Simmons et al., 2012). The rationale for focusing on these aspects of care was that these care activities often co-occur and must be provided daily (both in the morning and evening) and, as such, provide an opportunity each day for staff to offer residents choice during multiple aspects of care within one care delivery episode (Simmons, et al., 2011; Simmons et al., 2012; Sloane, Miller, Mitchell, Rader, Swafford & Hiatt, 2007). These care areas also were the focus of the larger staff training intervention to teach nurse aides how to offer residents choices during morning care.

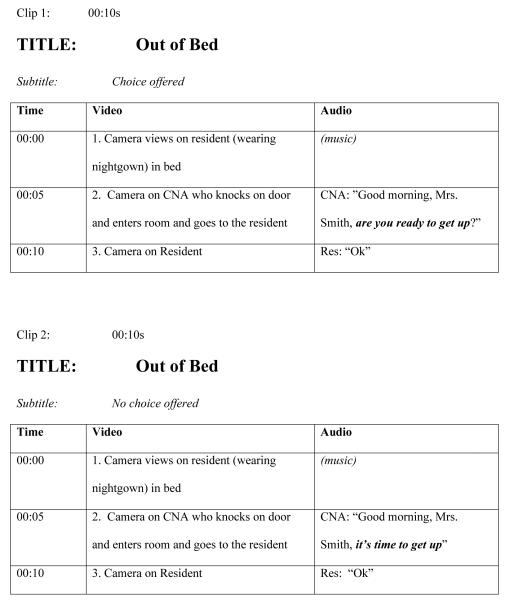

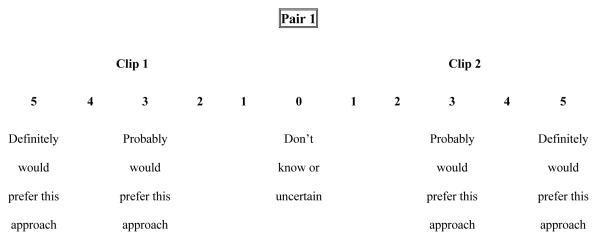

The video vignettes illustrated staff-resident interactions that featured choice at the point of care delivery in a concrete, specific way. The content of these video vignettes was based on actual observations of staff- resident interactions conducted in a previous observational study (Simmons et al., 2011). Each pair of vignettes depicted two nurse aide-resident interactions for each of the morning care activities (getting out of bed, toileting, dressing, and dining). In one vignette, the nurse aide is shown offering choice to the resident (e.g. “Would you like to use the toilet?”); in the paired vignette, the nurse aide does not offer choice (e.g. “It’s time to use the toilet now.”). The vignettes depicting choice or no choice were randomly sequenced to reduce possible bias. To further reduce possible bias, the staff member approached the resident in the same manner in each vignette (e.g., knocked on the door before entering, greeted the resident by name) and only varied whether or not choice was offered in the context of care delivery. Figure 1 presents a sample script. Each study participant was asked to independently complete an anonymous, forced-choice questionnaire that asked: (1) which of the two interactions s/he preferred; and (2) how much the respondent preferred it on a 5-point scale (see Figure 2). It is important to note that the vignettes were not labeled as choice or no choice and there was no pre-meeting discussion about choice or related topics as part of this or the larger study prior to the administration of the questionnaire.

Figure 1.

Sample Script for Video Vignettes Depicting Choice and No Choice

Figure 2.

Forced-Choice Preference Rating Scale for Paired Vignettes

Qualitative Evaluation

A focus group discussion facilitated by one of the study authors (PhD with prior experience in focus group research) was held immediately following the video vignette ratings. Each focus group was audio-taped and lasted an average of 36 minutes (range 32:37-40:38). Focus group participants were asked the following stem question: “Why did you rate some video clips more favorably than others?” An interview guide was used during the focus group interviews. Such guides provide broad interview questions that the researcher is free to explore and probe with interviewees. Interview guides are especially useful when, as in this case, little is known about the overriding research question (Morgan, 1993). Listed below are the broad interview questions and, under each, examples of probe questions used for follow up within the group discussions:

When you rated the clips, why did you rate some of them more favorably than others?

What went into that decision?

Why is that an important choice?

How would you want to be treated if you needed care in this facility?

How much do you value having a choice in your personal life and in your professional life?

Have you had instances in your life where you did not have any choice?

What instances can you think of where a resident has to have the choice made for them?

Are there some residents to whom it is harder to offer choices?

Are there times when you think a resident should not be offered a choice?”

The recordings were transcribed verbatim and then reviewed for accuracy by one of the study authors. The coding process was completed independently by two PhD-level researchers who discussed coding and reached consensus. Transcriptions were independently read numerous times to become immersed in the data and obtain overall and fundamental meaning of the interviews by two researchers. Consistent with standard analytical methods for focus groups (Morgan, 1993; Onwuegbuzie, Dickinson, Leech & Zoran, 2009) and constant comparison analysis (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009; Strauss & Corbin, 1998) a step-by-step process was used to code the text. In the first step, the data in the focus group transcript were clustered into smaller units and a code was attached to each unit. In the second step, differences and similarities in coding between the researchers were discussed until consensus was reached; then a coding scheme was developed that grouped the codes into categories. In the third step, themes were developed that expressed the content of the group and the transcript was re-coded using the coding scheme (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). In order to test if themes that emerged from one focus group also emerged in other groups, an emergent-systematic design was employed in which data were analyzed one focus group at a time (Onwuegbuzie et al., 2009). This design enables researchers to assess the meaningfulness of themes and refine the themes throughout the course of the study. Finally, quotes from focus group participants were identified to represent each theme by both independent raters and final representative quotes were chosen through discussion.

Results

Quantitative Evaluation

Table 1 provides the quantitative ratings (on a scale from 0, “don’t know or uncertain” to 5, “definitely would prefer this approach”) showing that both nurse aides and family members consistently rated the “choice” video vignettes as preferable to the “no choice” vignettes across all aspects of the selected morning care activities. The average preference ratings ranged from 4.22 to 4.94 for nurse aides and 3.78 to 5.00 for family members across the six paired vignettes. In each group, the lowest rating was assigned to the “time to get out of bed – 2 person assist” (pair 6) category (4.22 ± 0.67 and 3.78 ± 0.97 for nurse aides and family members, respectively). Otherwise, there was little variation in nurse aide or family ratings and no significant differences between the two groups for their preferences for choice to be offered during these aspects of morning care.

Table 1.

Percentage of participants who preferred “choice” and preference rating (N=32)

| Nurse Aide (N=17) | Family (N=15) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Percent (n)* | Rating** Mean (±SD) |

Percent (n) * | Rating** Mean (±SD) |

|

|

|

||||

|

Pair 1 Time Out of Bed- 1 Person Assist |

94% (16) | 4.94 (±0.25) | 100% (15) | 4.80 (±0.56) |

|

Pair 2 Toilet Use |

82% (14) | 4.93 (±0.27) | 100% (15) | 4.80 (±0.56) |

|

Pair 3 When to Dress |

88% (15) | 4.93 (±0.26) | 93% (14) | 4.36 (±0.93) |

|

Pair 4 What to Wear |

88% (15) | 4.93 (±0.26) | 80% (12) | 4.42 (±1.08) |

|

Pair 5 Dining Location |

94% (16) | 4.94 (±0.25) | 86% (13) | 5.00 (±0.00) |

|

Pair 6 Time Out of Bed- 2 Person Assist |

53% (9) | 4.22 (±0.67) | 60% (9) | 3.78 (±0.97) |

SD = standard deviation;

Percent (n) = Proportion who rated the “choice” video as preferable to the “no choice” video;

Rating: 0=”don’t know or uncertain” 5=″definitely would prefer this approach”

Qualitative Evaluation

The focus group discussions revealed that both nurse aide and family respondents recognized and preferred the vignettes in which choice was offered relative to the vignettes in which it was not. When participants were asked why they rated one vignette as more preferable than the other, a typical statement was, “It gave the resident a choice” [family] or “…asking them the question gives them a choice “[staff] (although some participants used the synonymous term “options”). In other comments, participants reflected on how they would want to be treated: “I would want somebody to pay attention to me, to talk to me even if I didn’t know what they were talking about or understood it” [family] and “Just don’t come in and tell me…give me a choice.” [family] Moreover, the nurse aides valued choice in their care roles. For example, one nurse aide observed, “No one likes to be told what to do.” [staff]

The qualitative analysis identified three themes related to the importance of offering choice among both family members and nurse aides: (1) resident well-being, (2) resident control, and (3) approach. Related to “resident well-being,” both groups said that offering choice to residents endorsed the residents’ well-being by communicating “respect” and “dignity” for the resident and acknowledged the resident’s “value as a person.”

The second theme, resident control, was recognized by all participants as a way of providing residents with some control over their daily life activities in an otherwise restricted care setting where they have little control. In transitioning to the nursing home, residents, said one participant, have control over their daily lives “stripped away from them.” [family]

The third theme, “approach”, concerned the way in which staff interacted with residents during care provision. This theme emerged from general discussions regarding resident respect and dignity by both staff and family members. Subjectively, when choice is offered to a resident, it apparently feels and looks like a better way to approach the resident. For example; “You have to be careful how you approach them. She gave the resident an option. Most of all it is the respect you give them. You have to approach them as adults.” [staff] Approach was defined as not just the words used by staff during care, but also the manner in which staff communicated with the resident, such as a “caring and kind manner,” or “their tone and demeanor.” [family] Approach was viewed as particularly important when residents had cognitive impairment or dementia, which limited their ability to understand staff and/or communicate their preferences. Participants in both groups agreed that choice should be offered even when residents were cognitively impaired or had limited ability to make decisions.

In response to the follow-up question, “Are there times when you think a resident should not be offered a choice”? staff focused on pragmatic issues. As one staff member stated, “ well it could be an emergency situation where they are sick and you have to get them ready to go to the hospital and …they will not put on clothes. This is a situation where there is no choice offered.” Staff and family respondents both mentioned staff workload and insufficient staffing as potential reasons why choice might not be offered every day: “It’s not that you’re not doing your job, you have so many residents that you just have to move on.”[staff] Other times, choice might not be offered due to the need to provide care for the health and well-being of the resident: “If [the resident] is soiled…that is a no brainer – it’s time to be changed whether they want to be changed or not.”[family] Both groups also cited the nursing home environment (e.g., insufficient seating in the dining room) as another reason for limiting or otherwise not offering choice to residents for some aspects of care. For example, one family member said “It is different if you are at home or in a nursing home…. Here they have meals… and if you want your hot meal you better have it now because you won’t have it later.”[family]

Another common example of when it was considered acceptable to not offer choice involved residents with dementia or depression. “If you don’t know where you are coming or going… okay, well fine... Somebody has to be in control.” [family] “Some are set in their depression and will sit all day and not want to do anything.” [staff] However, both staff and family said that you should still offer choice first because “you don’t know what a person’s mind set is from day to day or from hour to hour.” [family] Both groups also endorsed using encouragement rather than “forcing” the resident as the next step. “I guess the employee would help them and lead them into a decision.” [family] “You just have to keep trying. You have to use all kinds of approaches.” [staff]

Discussion

There is a growing emphasis on resident-centered care and the importance of offering residents choice during daily life activities in the LTC setting (Bowers et al., 2007; CMS, 2009, Doty et al., 2007). However, recent observational studies show that choice is offered infrequently during daily LTC practice (Schnelle et al., 2009; Simmons et al., 2011; Simmons et al., 2012). The purpose of this study was to determine if two LTC stakeholder groups – staff and family – rated choice as preferable when illustrated in specific staff-resident care scenarios. The results of this preliminary study showed that both families of residents and nurse aides strongly preferred staff-resident interactions in which choice was offered for specific aspects of morning care. There were no important differences between these two LTC stakeholder groups in either their preference ratings or reasons given for their ratings. The equally strong preference for choice expressed by both family and staff was somewhat surprising given that previous research has shown that lower socioeconomic status and minority groups, which characterized the nurse aide sample in this study, may value choice less (Markus & Schwartz, 2010). The reasons given for both staff and family preferences for choice mirrored the opinions documented in the professional literature for why choice is valued by various LTC stakeholders (Kane et al., 1997; King et al.., 2012; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Simmons et al., 2011). Resident well-being, sense of control, dignity and respect, and respondents’ own personal values related to how they would want to be treated were common themes that emerged in this study for why choice is important. This recognition of the importance of choice among both staff and families of LTC residents should facilitate recent efforts to improve staff provision of choice (CMS, 2009; Boscart, 2009, Simmons et al., 2011).

Equally important, the results of this preliminary study also revealed potential reasons why choice may not be offered consistently in daily LTC practice. These reasons included heavy staff workload (e.g., being short-staffed or having residents that require a 2-person assist), care environment limitations (e.g., inadequate seating in dining room, scheduled mealtimes), and care requirements (e.g., incontinence) that often prohibited or decreased the likelihood that staff would offer choice to residents at the point of care delivery. These staff-reported reasons for not offering choice are consistent with the results of previous studies (Bowers, Lauring & Jacobson, 2001; Kane et al., 1997; Kalisch, 2006; Lopez, 2006; Schnelle et al., 2004; Simmons et al. 2012). Moreover, a recent observational study showed that residents who required two staff for transfer out of bed did not receive any aspects of morning care until after 11am. In short, not only were these physically-dependent residents not offered choices about morning care, they had to wait a prolonged period of time to receive care at all due to their higher care burden (Simmons et al., 2012).

In some cases, resident characteristics, such as depression and cognitive impairment, were mentioned as reasons why choices sometimes have to be made by the staff for the resident although, even in these cases, respondents noted that the staff approach – or manner of care -remained important. It is noteworthy that neither stakeholder group reported that staff knowledge of the resident or consistent staff-resident assignment precluded the importance of offering choice. Instead, both staff and family recognized that resident preferences could change from day-to-day, at least in the morning care areas that were the focus of this study, and offering choice during each staff-resident care encounter remained important.

This study has a few limitations. The study sample was small and represented only three LTC facilities in one geographic area; thus, these preliminary findings may not be generalizable to all nursing home staff or family members. This study also was focused on only specific aspects of morning care and there are many other aspects of residents’ daily lives that offer the opportunity for choice but which were not addressed in this study (e.g., social activities, meal service, bathing schedule, evening bedtime schedule). In addition, LTC residents were not included in this study; and, staff and families often provide different ratings of residents’ quality of life compared to residents themselves (Crespo, Bernaldo de Quiros, Gomez & Hornillos, 2011; Kane et al., 1997). Despite these limitations, the consistent finding that the choice vignettes were “strongly preferred” by both stakeholder groups suggests that this preference for choice is robust and, thus, likely to extend to other aspects of daily care provision in the LTC setting. However, a replication study with a larger sample and inclusive of additional care areas is recommended.

There are several practice and research implications based on these preliminary findings. First, as mentioned previously, there seems to be a disconnect between staff self-reports of desirable care behavior (offering choice) and how care is actually delivered in care practice (Schnelle et al., 2009; Simmons et al., 2011; Simmons et al., 2012). This disconnect may be, at least partially, explained by some of the reasons reported in this study for not offering choice, such as staff workload and care environment limitations or residents with limited ability to make informed choices. A hospital-based study showed similar findings in which nurses reported that they valued offering choice to patients and, at the same time, reported using strategies to limit choice if they believed these strategies improved staff workflow or was in the best interest of the individual patient (Draper, 1996). Thus, understanding the reasons for inconsistencies in resident-centered care can help to inform interventions to improve care as it relates to choice.

Second, because staff workload was expressed as a primary reason for not offering choice in the care areas of interest in this study, future research efforts should determine how much staff time, if any, is added to a staff-resident care interaction when choice is offered. In this study, some families suggested that, based on their previous experiences as a caregiver for their relative, offering choice increased the level of cooperation with the care recipient (resident), which suggests it might actually be less labor intensive if it is related to a reduction in resistance to care events, for example. Furthermore, observational studies (Schnelle et al., 2009; Simmons et al., 2011; Simmons et al., 2012) indicate that there are subtle differences in the way staff offer choice from direct, specific options (“would you like to get up now or later?) to simply asking the resident’s permission to provide care (“I’m going to help you out of bed now, okay?”). Similarly, staff may verbally offer a choice but proceed to provide care according to their own routinized schedule such that the resident doesn’t truly have an option or staff may delay care provision altogether due to the anticipated time it is going to require for a physically dependent resident. As acknowledged by both staff and families in this study, even when choice may not be possible, it is the way in which staff approach the resident to communicate both dignity and respect that remains important. Video vignettes similar to those used in this study could be developed in future work to illustrate these subtle yet key aspects of how to provide resident-centered care.

Finally, because families strongly preferred the vignettes in which choice was offered to residents, efforts should be made to increase their awareness of how choice should be incorporated into daily LTC practice, which may make family members better advocates for such care when visiting their relatives. The results of this study suggest that future efforts to train LTC staff in providing resident-centered care might benefit from explicit examples of how to offer choice using video vignettes similar to those used in this study (refer to the Choice module at http://www.VanderbiltCQA.org) as well as staff training that addresses common obstacles which might hinder the ability of staff to routinely provide choice to move us beyond new regulations to real change in daily care practice.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institute of Health grant number RO1AG032446 and VA Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Merit Grant IRR 07-250. Support for Dr. Rahman was provided by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (T32AG0037).

References

- Boscart VM. A communication intervention for nursing staff in chronic care. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2009;65(9):1823–1832. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers BJ, Lauring C, Jacobson N. How nurses manage time and work in long-term care. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;33(4):484–491. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers B, Nolet K, Roberts T, Esmond S. Implementing Change in Long-Term Care: A Practical Guide to Transformation. Commonwealth Fund; New York, NY: 2007. [Online]. Available: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Content/Innovations/Tools/2009/Apr/Implementing-Change-in-Long-Term-Care-Bowers.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Letter to State Survey Agency Directors. CMS; Baltimore, MD: 2009. Nursing Homes - Issuance of Revisions to Interpretive Guidance at Several Tags, as Part of Appendix PP, State Operations Manual (SOM), and Training Materials. [Online]. Available: http://www.cms.gov/SurveyCertificationGenInfo/downloads/SCletter09_31.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Christenson AM, Buchanan JA, Houlihan D, Wanzek M. Command use and compliance in staff communication with elderly residents of long-term care facilities. Behavioral Therapy. 2011;42(1):47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo M, Bernaldo de Quiros M, Gomez MM, Hornillos C. Quality of life of nursing home residents with dementia: A comparison of perspectives of residents, family, and staff. The Gerontologist. 2012;52(1):56–65. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty MM, Koren MJ, Sturla EL. Findings from The Commonwealth Fund National Survey of Nursing Homes. Commonwealth Fund; New York, NY: 2008. Culture Change in Nursing Homes: How Far Have We Come? 2007. [Online]. Available: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Content/Publications/Fund-Reports/2008/May/Culture-Change-in-Nursing-Homes--How-Far-Have-We-Come--Findings-From-The-Commonwealth-Fund-2007-Nati.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Draper P. Compromise, massive encouragement and forcing: a discussion of mechanisms used to limit the choices available to the older adult in hospital. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 1996;5(5):325–331. doi: 10.1111/jocn.1996.5.5.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch BJ. Missed nursing care: A qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Care Quality. 2006;21(4):306–313. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200610000-00006. doi:10.1097/00001786-200610000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RA, Caplan AL, Urv-Wong EK, Freeman IC, Aroskar MA, Finch M. Everyday matters in the lives of nursing home residents: wish for and perception of choice and control. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1997;45(9):1086–1093. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb05971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kheirbek R. Innovations in nursing home care: Culture transformation in VA. (n.d.) Retrieved from: http://www1.va.gov/geriatricsshg/docs/CultureTransformationProgressReport.doc.

- King J, Yourman L, Ahalt C, Eng C, Knight SJ, Perez-Stable EJ, Smith AK. Quality of life in late-life disability: “I don’t feel bitter because I am in a wheelchair”. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03844.x. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03844.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez SH. Culture change management in long-term care: A shop-floor view. Politics & Society. 2006;34(1):55–79. DOI: 10.1177/0032329205284756. [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR, Schwartz B. Does choice mean freedom and well-being? Journal of Consumer Research. 2010;37:344–355. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DL. Successful Focus Groups Advancing the State of the Art, Chapter 8 Quality Control in Focus Group Research. Sage Publications; Newbury Park: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Neupert SD, Allaire JC. I think I can, I think I can: Examining the within-person coupling of control beliefs and cognition in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0026447. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1037/a0026447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Dickinson WB, Leech NL, Zoran AG. A Qualitative Framework for Collecting and Analyzing Data in Focus Groups. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2009;(8):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schnelle JF, Bertrand R, Hurd D, White A, Squires D, Feuerberg M, Hickey K, Simmons SF. Resident choice and the survey process: The need for standardized observation and transparency. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(4):517–24. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnelle JF, Simmons SF, Harrington C, Cadogan M, Garcia E, Bates-Jensen BM. Relationship of nursing home staffing to quality of care. Health Services Research. 2004;39(2):225–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00225.x. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, Durkin DW, Rahman A, Choi L, Beuscher L, Schnelle JF. Resident characteristics related to the lack of morning care provision in long term care. The Gerontologist. 2012 doi: 10.1093/geront/gns065. doi:10.1093/geront/gns065. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons SF, Rahman A, Beuscher L, Jani V, Durkin DW, Schnelle JF. Resident-directed long term care: Staff provision of choice during morning care. The Gerontologist. 2011;51(6):867–875. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr066. (DOI: 10.1093/GNR066) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloane PD, Miller LL, Mitchell CM, Rader J, Swafford K, Hiatt S. Provision of morning care to nursing home residents with dementia: Opportunity for improvement? American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2007;22(5):369–377. doi: 10.1177/1533317507305593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. 2nd ed Sage; Thousand Oaks: 1998. [Google Scholar]