Abstract

Background:

The concept of the street child in rural communities has received little attention. This study describes the sociodemographic characteristics of the street children found in a group of rural communities.

Method:

This descriptive study is nested in a cross sectional analytical study of street children in a group of rural communities undergoing urbanization. A cluster sample of street children as defined by the United Nations was taken in the seven chosen political wards.

Results:

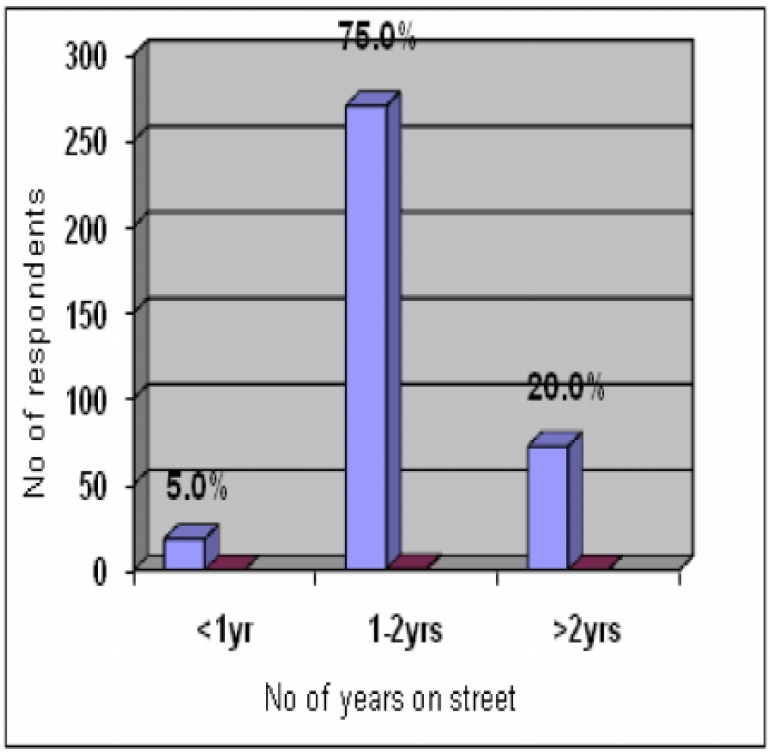

Majority of the street children (88.9%) were within the age group 15-17 years with more males (58.3%) than females (41.7%). Up to 64.7% had attained secondary level education while only 3.9% had no formal education. A high percentage, (61.4%) were still attending school and 15.8% had no work. Of those who work on the streets, being an apprentice (16.4%), petty trading (15.0%), part-time driving (9.5%) and car washing (5.0%) were the commonest types of work. Of those still schooling, 41.6% had no form of part-time work on the streets. None of the street children lived on the street with 65% still living with parents. However, 75% had been involved in the street life for 1-2 years with a median time of 2 years. More than 30% of their parents work outside town.

Conclusion:

The street child in rural communities differs from the urban perception which often has to do with those living rough and existing outside the family framework. More studies would be needed on the driving factors for street life in rural communities undergoing urbanization.

Keywords: Street children, rural communities, socio-demographic characteristics.

INTRODUCTION

The term street children has many definitions in different settings. Perhaps demonstrating the fact that street children are not a homogeneous group and that the particular circumstance dictates who should be included in the definition. Generally speaking, four categories of street children have been described and these are: children of the street; children on the street; children who are part of a street family; and those in institutionalized care1; but as observed by Aptekar and Heinonen2, this classification is too rigid. The definition does not reflect the cultural diversities across and within countries as well as the transitional pattern that sometimes occur within the same street children’s lifetime. This variability reflects differing socio-economic and cultural contexts across countries3.

The United Nations defined the term ‘street children’ to include “any boy or girl… for whom the street in the widest sense of the word… has become his or her habitual abode and/or source of livelihood, and who is inadequately protected, supervised, or directed by responsible adults4. It follows therefore that all children found in or on the street would fall into this category. Such children must have been observed to spend a substantial part of their time on the street. They are usually classified based on the activities they are involved in on the street. However, getting information about street children is difficult. As posited by a study amongst street children in Ibadan, the street child population is a mobile one; so, generally speaking, the universe of the street child is difficult to determine5. The Civil Society Forum puts it more succinctly by saying that: “There are no known statistics of street children in Nigeria6.

Another problem with defining street children across cultural diversities is their frequent association with negative events. For example, in Addis Ababa the term reinforces a negative image as they are collectively referred to as Borco (meaning pig) 2. In Romania, this negative attitude to a certain type of these children is overcome by calling them “Children in Conflict with the Law” (CICL) which is reflective of international concerns for the promotion of the child’s sense of dignity and worth7. In Nigeria, a peculiar type of street children known as the “area boys and girls” who are school drop-outs have been known to provide unsolicited security and praise singing to apparently successful individuals living or passing through their “territories”. A Lagos study noted that they were at higher risk of getting involved in hard drug use and/ or peddling8. Furthermore, rightly or wrongly many have anecdotally attributed the increase in violent crime in the society to them.

Central to all these definitions is the fact that the issue of street children is often thought of as an urban phenomenon brought about by trends in urbanization and poverty9. However, Heinonen found that poverty is a necessary but not sufficient condition that spurs many children to street life, since many poor children in Addis Ababa do not become street children10. Other reasons that have been cited for life on the streets are family problems including mistreatment, lack of family, work demands at home and desire to be with friends1. Also, the concept of the street child in a rural community has received little attention with many believing that it is a rarity. But with the urbanization trends and development of rural communities, the street child may become apparent in these communities. Thus studies are needed to verify the reality of this hypothesis. This report is part of a larger study which documented the phenomenon of the street children in a rural local government. In this report, we describe the socio-demographic characteristics of the street children found in this Local Government Area.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and location

This study was nested in a large cross-sectional analytical study of street children in the Kajola Local Government area of Oyo State in the South-Western region of Nigeria. Itesiwaju Local Government bound the Local Government in the north. It is also bounded in the south by Ibarapa Local Government, in the east by Iseyin Local Government and in the west by Iwajowa Local Government. According to the 1991 Census, the Local Government Area (LGA) has a population of one hundred and fifty eight thousand, six hundred and ninety-eight (158,698)11.

The Yorubas mainly inhabit communities within the LGA. Though there are a handful of other ethnic groups such as Igbo, Hausa, Fulani, Bororo and Igede. This arises because the LGA lies along the trans-border route, and this is also responsible for the transitional nature of the LGA (i.e., the slowing growing urbanization). The main occupations include farming, cloth weaving and pot making. Other means of livelihood within the community are tailoring, hairdressing, petty trading, civil service and trans-border trading. Transport business also thrives in this town because of the trans-border nature of the town. The local government area (LGA) contains six towns and 117 villages. The LGA is also divided into 11 political wards.

Sampling technique

Seven wards in the LGA were chosen by simple random sampling, while the areas where street children aggregate in the selected wards, like market places and garages, were identified and classified as clusters. A random sample of two clusters in each chosen ward was selected. Our major inclusion criteria were: children working on the streets or spending a large percentage of their lives, including sleeping on the street, partaking in street life and frequent presence at aggregation points even at odd hours4. Minor additional criteria included loose appearance and language. However, respondents were not included in the absence of the major criteria. We excluded those in institutionalised care. All individuals meeting the inclusion criteria and identified with the assistance of their peer group leaders were recruited for the study after informed consent was given. The survey was then conducted using an anonymous semi-structured questionnaire. This instrument was pretested among a small cluster of street children in Okeho that were not part of the study. The instrument was translated to Yoruba, the predominant language in the area and back translated to English language to ascertain construct validity. After the pretest, ambiguous questions were rephrased. The author conducted the interviews in Yoruba with the assistance of one communication arts graduate and eight health staff from the Primary Health Care Department of Kajola Local Government. The author trained these research assistants on the research instrument. Interviews were conducted between 8.00a.m. and 12 noon and also in the evening hours of 16.00 and 18.30.

With precision set at 5%, the calculated sample size was 227, and this was multiplied by 1.5 (design effect) to give a minimum sample size of 340. However, 360 street children eventually participated in the study. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital Joint Ethical Review Committee.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows that majority of the street children were within the age range of 15-17 years accounting for 88.9%. Males (58.3%) were more than females (41.7%).

Table 1:

Socio-demographic characteristics

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | ||

| 9-11 | 2 | 0.5 |

| 12-14 | 38 | 10.6 |

| 15-17 | 320 | 88.9 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 210 | 58.3 |

| Female | 150 | 41.7 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 304 | 84.4 |

| Co-habiting | 20 | 5.6 |

| Co-habiting relationship described as binding | 36 | 10.0 |

| Highest level of education completed | ||

| No formal education | 14 | 3.9 |

| Primary | 37 | 10.3 |

| JSS1-3 | 76 | 21.1 |

| SSS1-3 | 233 | 64.7 |

| Employment status | ||

| Student | 221 | 61.4 |

| Work fully | 82 | 22.8 |

| Unemployed | 57 | 15.8 |

| Place of residence | ||

| With parents | 234 | 65.0 |

| With friends | 26 | 7.2 |

| Alone | 25 | 6.9 |

| +Others | 75 | 20.8 |

partners place, relatives and other acquaintances

Majorityy of the children were single 304 (84.4%) while only 10.0% were in cohabiting relationships that they described as binding and lasting. Majority (64.7%) had completed their education up to between senior secondary school 1 and 3 while only 3.9% had no formal education. Many of these children 221 (61.4%) also still attend school. On the other hand, 57 (15.8%) weren’t in any employment and 22.8% had a full time occupation on the streets. Many of the students 234 (65.0%) also live with their parents with only 6.9% living alone. Table 2 shows that of the 211 who had a form of work on the street, 36 (16.4%) were apprentices followed by traders (15.0%). Out of the students, 92 did not really have any work on the streets.

Table 2:

Employment characteristics of those that work on the streets

| Occupation *N =211 | no | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Apprentice | 36 | 1.4 |

| Trading | 33 | 15.0 |

| Part-time driving | 21 | 9.5 |

| Car washing | 11 | 5.0 |

| Hawking | 10 | 4.5 |

| Illegal mining | 6 | 2.7 |

| **Others | 3 | 16.4 |

In addition to the 57 unemployed non-students, 92 of the students do no work on the streets

intermediaries/middlemen

Table 3 reveals that 19 (5.3%) of the street children had lost both parent while 298 (82.7%) still have their parents living. The respondents fathers were mainly farmers (23.8%) followed by traders (21.9%) and artisans (16.2%). The major occupation of respondents mothers were trading (64.6%) followed by a professionals such as nurses, teachers, engineers, e.t.c. (13.7%) and farming (12.5%). Also majority of the fathers and mothers worked within the town (66.1% and 68.9% respectively). In addition, only in 9.1% of cases were the parents divorced with 75.5% of the parents of the street children still married and living together.

Table 3:

Parental characteristics

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Which of your parents is dead? | ||

| Both alive | 298 | 82.7 |

| Mother dead | 15 | 4.2 |

| Father dead | 28 | 7.8 |

| Both parents dead | 19 | 5.3 |

| *Father’s occupation | ||

| Farming | 75 | 23.8 |

| Trading | 69 | 21.9 |

| Artisan | 51 | 16.2 |

| Driving | 45 | 14.3 |

| Professional | 43 | 13.6 |

| #Others | 32 | 10.2 |

| *Mothers occupation | ||

| Trading | 212 | 64.6 |

| Professional | 45 | 13.7 |

| Farming | 41 | 12.5 |

| Artisan | 15 | 4.6 |

| #Others | 15 | 4.6 |

| *Father’s usual place of work | ||

| Within town | 209 | 66.1 |

| Outside town | 107 | 33.9 |

| *Mother’s usual place of work | ||

| Within town | 226 | 68.9 |

| Outside town | 102 | 31.1 |

| **Parental marital status | ||

| Married and together | 225 | 75.5 |

| Separated but not divorced | 46 | 15.4 |

| Divorced | 27 | 9.1 |

Does not add up to 360 because mother or father is dead or not working

Only those that both parents are alive are included

The unemployed and those who do bits of this and that

DISCUSSION

This study has clearly shown that the concept of the street child has a different meaning from the urban concept. Majority of the identified street children were within the age group 15-17 years while even a child of 9 years was also recruited for the study. Males were also more than females. It has been known especially in the big cities to find children as young as eight years on the streets. However, in the Lusaka study, the proportion of street children between the ages of 12 and 16 years was 60%9. Another study puts the ages of respondents between 8 and 18 years5. The gender of street children varies from place to place, but WHO puts the proportion of girls among street children to be less than 30% in developing countries1. A similar finding was reported from the Lusaka study which puts the proportion of girls at 20%9. In our own study, the proportion of females was more than 40%. That the majority of street children still live with their parents reflects the fact that although the family system is gradually breaking down, there is still recognition of kinship in the rural areas. Thus, the young are still accommodated within the family dwelling place. In contrast, some studies have reported that street children have little contact with their families12,13. However our observation of street children still living with their parents is similar to a finding among a sample of street and working children in Addis Ababa which reported that at least 95% had regular contacts with their families10. That a substantial proportion of the street children still attend school may be quite paradoxical if street children are not defined in terms of “the habitual abode and/or source of livelihood”. However our study has brought forth a peculiar type of street children who still attend school but are likely to eventually abandon school due to the lack of adult supervision and street influence on them. These children also form a bridging population that could introduce unhealthy behaviour to the schools they attend since a sizeable proportion of them have been on the streets for between 1 and 2 years with the likelihood of acquiring bad habits on the streets.

There was not much difference from published literature concerning the occupation of street children, as apprenticeship, part-time driving/touting, car washing, hawking and non-specific jobs like praise singing were amongst their sources of livelihood1,5,7. Children of such professionals like nurses, engineers and teachers were also found on the streets. Perhaps reflecting the observation by Heinonen10, that poverty is a necessary but not sufficient condition that spurs many children to street life. While further study would be needed to unravel the current driving forces to the street in rural areas as the reasons why children go to the streets have changed over time2, other reasons that have been documented as responsible for life on the streets are family problems including mistreatment, lack of family, work demands at home and desire to be with friends1.

The parental characteristics shows clearly that majority of the street children still come from “apparently stable families” (i.e., 75.5% were married and together), thus differing from the urban perception of street children. Despite being married and together, more than thirty percent of the fathers and about the same proportion of the mothers of these street children work “out of town”. Situations in which parents work outside the areas within which their children are domiciled may actually make a child more vulnerable to negative peer group influences especially if no other adult is responsible for the supervision of the child while the parent is away. This may partly be the reason for the observation that a sizeable number of currently schooling students were found on the streets partaking fully in street life. Although our study did not document this, the still schooling street children in this study may likely have gravitated to the streets due to the lack of recreational facilities to keep youths occupied after school hours in the rural areas. As at the time of study, no amusement parks, cinemas and other recreational places exists in the Local Government Area. It is known that youths that lack access to facilities that engages their attention and energy while under supervision of responsible adults are prone to boredom and its associated attraction to run risks14.

Overall, it could be said that the phenomenon of the street child in the rural perspective differs from the urban perception which is largely concerned with those usually living rough and existing outside the family framework15. We thus recommend that further studies be conducted on the phenomenon of the street child in rural and/or peri-urban communities. We also suggest that the sub-set of street children who gravitate to the street solely due to the desire to be with friends or to seek pleasure (as shown by still schooling students who had no job on the streets) be put in a category to be referred to as “children about the street” as distinct from children on the street.

Figure 1.

shows that 270 (75%) of the respondents had spent between 1 and 2 years on the streets with a median of 2 years.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organisation. Working with street children. WHO/MSD/MDP/00.14. 1995.

- 2.Aptekar, Lewis, Heinonen “Methodological Implications of Contextual Diversity in Research on Street Children”. Children, Youth and Environments. 2003 Spring;13(1 ) Retrieved [14/8/2007] from http://colorado.edu/journals/cye . [Google Scholar]

- 3.United Nations. Economic and Social Council. World situation with regard to drug abuse, with particular reference to children and youth. 2001;7:25–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panter-Brick C. Street Children, Human Rights and Public Health: A Critique and Future Directions’. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2002. pp. 147–71.pp. p4

- 5.Morakinyo J, Odejide A.O. A community based study of patterns of psychoactive substance use among street children in a local government area of Nigeria: Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;00:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.A Civil Society Forum for Anglophone West Africa on promoting and protecting the rights of street children. 2004.

- 7.Rodica Gregorian, Elena Hura-Tudor, Thomas Feeny., editors. Asociatia Sprijinirea Integrarii Sociale in partnership with The Consortium for Street Children. Street Children and Juvenile Justice in Romania.

- 8.Ekpo M, Adelekan M.L, Inem A.V, Agomoh A, Agboh S, Doherty A. Lagos “Area boys and girls” in rehabilitation: their substance use and psychosocial profiles. East Africa Med J. 1995;7(5 ):311–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Project Concern. Rapid assessment of street children in Lusaka: fountain of hope, Flame Jesus Cares Ministry. Lazarus. Zambia. 2002.

- 10.Heinonen P. Anthropology of Street Children in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Durham, Durham, U. K. 2000 referenced in Aptekar L and Heinonen P. Methodological Implications of Contextual Diversity in Research on Street Children. Children, Youth and Environments. 2000;13(1) [Google Scholar]

- 11.National population Census, Nigeria. National Population Commission (NPC) 1991.

- 12.Aptekar L. “Street Children in Nairobi, Kenya: Gender Differences and Mental Health”. Journal of Psychology in Africa. 1997;2:34–53. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aptekar L, Abebe B. “Conflict in the Neighborhood: Street Children and the Public Space”. Childhood. 1997;4(4 ):477–490. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark C, Uzzell D.L. The affordances of the home, neighbourhood, school and town centre for adolescents. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2002;22:95–108. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hodges A, editor. National Planning Commission, Abuja and UNICEF NGERIA. Children’s and Women’s Rights in Nigeria: A wake-up call. Situation assessment and analysis. 2001. pp. 185–213.