Abstract

Objective

Violence toward others is a serious problem among a subset of military veterans. This study reports on predictive validity of a brief screening tool for violence in veterans.

Methods

Data on risk factors at an initial wave and on violent behavior at 1-year follow-up were collected in two independent sampling frames: (a) a national random sample survey of 1090 Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, and (b) in-depth assessments of 197 dyads of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans and collateral informants.

Results

We chose candidate risk factors—financial instability, combat experience, alcohol misuse, history of violence and arrests, and anger associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—based on empirical support in published research. Tools measuring these risk factors were examined, and items with the most robust statistical association to outcomes were selected. The resultant 5-item clinical tool, the Violence Screening and Assessment of Needs (VIO-SCAN), yielded area under the curve (AUC) statistics ranging from .74 – .78 for the national survey and from .74 – .80 for the in-depth assessments, depending on level of violence analyzed using multiple logistic regression.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, the VIO-SCAN is the first empirically-derived assessment tool for violence developed specifically for military veteran populations. As in civilians, past violence and arrest history had a robust association with future violence in veterans. Analyses show that individual factors examined in isolation (e.g., PTSD, combat experience) do not adequately convey a veteran’s level of violence risk; rather, as shown by the VIO-SCAN, multiple risk factors need to be taken into account in tandem when assessing risk in veterans. Use of evidence-based methods for assessing and managing violence in veterans is discussed, addressing benefits and limits of integrating risk assessment tools into clinical practice.

Violence to others is an issue of increasing concern among military veterans (1–5). Research has examined violent behavior among veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan (2–6) and previous eras of service (7–11). To date, however, clinicians have little direction for gauging what level of risk a veteran poses in the near future (12). Admission and discharge decisions and community treatment planning would be enhanced by research that directly informs, and possibly improves, decision-making and resource allocation in these clinical contexts (13).

Evaluations grounded in a structured framework and informed by empirically supported risk factors improve the assessment of violence (14–18). In civilian populations, significant progress has been made toward identifying risk factors empirically related to violence (17, 19–21) and combining these statistically into actuarial or structured risk assessment tools such as the Classification of Violence Risk (COVR)(22) and the HCR-20(19) to aid clinicians evaluating violent behavior (20, 21, 23, 24).

No comparable research exists for military veterans. Although studies identify correlates of violence in veterans (2, 6, 11, 25, 26), to our knowledge, veteran-specific factors have yet to be combined statistically into an empirically supported, clinically useful tool for assessing violence. Neither combat exposure nor military duty necessarily renders a veteran at greater risk of violence than civilians (13); however, violence risk assessment tools incorporating potentially relevant factors unique to veterans (e.g., war zone experience, associated psychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder) are not yet available. The current study reports on the validity of a brief screen for violence in veterans.

Method

Participants and Procedures

We employed the same measures and 1-year time frame in two sampling frames, (a) a national survey and (b) in-depth assessments of veterans and collateral informants. The national survey queried self-reported violence in a random sample of all veterans who served after September 11, 2001. The in-depth assessments probed multiple sources of violence in a self-selected regional sample of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Given strengths and weaknesses of each approach, we reasoned that statistical concordance of a set of risk factors for predicting subsequent violence in two disparate sampling frames would provide a viable basis for a risk screen.

National Survey

The National Post-Deployment Adjustment Survey, originally drawn by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Environmental Epidemiological Service in May 2009, consisted of a random selection from over 1,000,000 U.S. military service members who served after September 11, 2001 in Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF) or Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) and were, at the time of the survey, either separated from active duty or in the Reserves/National Guard. Veterans were surveyed using Dillman methodology (27) involving multiple, varied contacts to maximize response rates. Two waves of parallel data collection were implemented one year apart; participants were reimbursed after each wave. Risk factors at the initial wave and violence at follow-up were analyzed in the current paper.

The initial wave of the survey was conducted July 2009 to April 2010, yielding a 47% response rate and 56% cooperation rate, rates comparable to or greater than other national surveys of veterans in the U.S. (28–30) and U.K. (31). Details are found elsewhere (32) regarding sample generalizability of 1388 veterans completing the initial assessment; analysis showed little difference on available demographic, military, and clinical variables between those who took the survey after the first invitation versus after reminders, between responders versus non-responders, and between paper versus web survey completers.

One-year follow-up was conducted from July 2010 to April 2011, with 1090 veterans completing an identical follow-up survey, a 79% retention rate. Multiple regression revealed younger age and lower income predicted attrition, perhaps reflecting higher residential instability; other variables and violence were non-significant. Although estimated models accounted for 4% of attrition variance, the achieved retention rate was relatively high. To our knowledge, this national survey enrolled one of the most representative samples of U.S. OIF/OEF veterans to date.

In-Depth Assessments

The second sampling frame involved in-depth assessments of veterans and collateral informants at the Durham VA Medical Center. Participants were self-selected OIF/OEF veterans recruited through multiple approaches, including clinician referrals, advertisements, targeted mailings, and enrollment in the Veterans Affairs Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC) Registry Database for the Study of Post-Deployment Mental Health.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained before data collection, which spanned June 2009 to March 2013. To be eligible for the in-depth assessments, veterans must have served in the U.S. military after September 11, 2001 (as in the national survey). Veterans selected a close family member or friend to serve as collateral informant. If both agreed to participate, data collection was scheduled at the Durham VA Medical Center. After a complete description of the study was provided, written informed consent was obtained. Assessments were conducted separately with the veteran and collateral informant and included self-report measures and face-to-face interviews.

Corresponding to the survey, the time frame for the in-depth assessments was one year, in which three waves of data collection occurred six months apart. For each wave, veterans and collateral informants provided data and were reimbursed. In the current paper, risk factors at the initial assessment and violence at follow-up assessments were analyzed using measures parallel to those in the national survey. Of the original 320 veteran-collateral dyads who completed the initial wave, 197 pairs were retained at one year (retention rate = 62%). Attrition related to male gender and alcohol misuse, accounting for 16% of the variance.

Measures

At initial data collection in the national survey and in-depth assessments, risk factors were measured based on variables associated with violence in empirical research on veterans (12). Candidate risk factors included financial instability, combat experience, alcohol misuse, history of violence/arrests, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

To construct a brief screen, we used single items to measure financial instability and history of violence/arrests. Combat experience, alcohol misuse, and PTSD were originally measured with scales, but in constructing a brief risk screen, we identified the single item on each scale with the strongest statistical association to violence. To do this, we entered scale items into bivariate correlation matrices, repeating this analysis for both sampling frames and at different levels of the violence outcome. From the matrices, we selected the single scale item with the strongest association.

For financial instability, we used an item on the Quality of Life Interview(33): “Do you generally have enough money each month to cover the following? Food, clothing, housing, medical care, traveling around the city for things like shopping, medical appointments, or visiting friends and relatives, and social activities like seeing movies or eating in restaurants?” (0= yes; 1 =no).

For combat experience, we examined items from the combat exposure subscale of the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI) (34). Endorsing one or both of the following had the most robust relationship with outcomes: “I personally witnessed soldiers from enemy troops being seriously wounded or killed” or “I personally witnessed someone from my unit or an ally unit being seriously wounded or killed” (1=yes; 0=no).

For alcohol misuse, we used the item from the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (35) that showed the strongest correlation with outcomes: “Has a relative or friend, or a doctor or other health worker, been concerned about your drinking or suggested you cut down?” (1=yes; 0=no).

For history of violence and arrests, participants indicated whether they had previously been arrested or been violent toward others, excluding controlled aggressive behavior conducted during combat duties (1=yes; 0=no).

For PTSD, participants had to meet criteria for probable PTSD on the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS>48) (36, 37) and report frequent anger on the following DTS item: “In the past week, how many times have you been irritable or had outbursts of anger?” (1= ≥ 4 times + probable PTSD; 0= other).

At follow-up data collection for both sampling frames, violent behavior was operationalized as in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study (17). Severe violence was coded 1 if participants endorsed specific items on the Conflict Tactics Scale (38) (i.e., “Used a knife or gun,” “Beat up the other person,” or “Threatened the other person with a knife or gun”) or the MacArthur Community Violence Scale(39) (i.e., “Did you threaten anyone with a gun or knife or other lethal weapon in your hand?,” “Did you use a knife or fire a gun at anyone?,” or “Did you try to physically force anyone to have sex against his or her will?”) in the past year. Other physical aggression was coded 1 if participants endorsed other items on these scales (i.e., kicking, slapping, using fists, and getting into fights) in the past year. A composite of any violent behavior was coded 1 if participants endorsed severe violence and/or other physical aggression in the past year.

Identical questions and coding for dependent variables were used in both sampling frames. The surveys measured violence/aggression by self-report at a 1-year follow-up, whereas assessments occurred at 6 months and 1 year and gathered information about veterans’ violence/aggression from self-report and collateral sources. Research finds considerable agreement between veteran self-report and collateral reports of violence; specifically, a study of veterans measuring violence using both self-report and collaterals revealed that 80% of cases positive for violence were determined relying on self-report only (40). This finding is consistent with civilian studies using multiple sources for measuring violence (41).

Statistical Analysis

SAS 9.3 software was used for analyses. For the national survey, women were oversampled to ensure adequate representation. Females comprised 33% of the survey sample but 15.6% of the military at the time of data collection (42); accordingly, survey data were down-weighted to reflect the prevailing military proportion, rendering a weight-adjusted N=866. In-depth assessments were not weight-adjusted but included collateral information on violence.

Statistical analyses were conducted in parallel for survey and assessment data. Analyses included descriptive statistics characterizing the two samples and Spearman correlations between initial-wave single-item risk factors and follow-up violent behavior (any violence, severe violence, other physical aggression) measured in the next year.

For both sampling frames, we employed multiple logistic regressions specifying five items representing risk factors as independent variables and violence outcomes as dependent variables. Scores from the single items were additively combined into a total score, which was also regressed onto violence outcomes for both sampling frames.

Regression analyses were used to derive receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of sensitivities versus (1 – specificities), with area under the curve (AUC) providing an index of predictive validity. Predicted probabilities of severe violence in the next year were generated based on the total risk screen score at the initial wave.

Results

Characteristics of the national survey and in-depth assessment samples are presented (Table 1). Analyses showed veterans in the in-depth assessments had higher incidence of risk factors compared to survey participants, including financial problems (41% vs.38%), witnessing others wounded (46% vs. 40%), PTSD (29% vs. 18%), alcohol misuse (31% vs. 24%), and previous violence/arrests (47% vs. 22%).

Table 1.

Description of National Survey and In-Depth Assessment Samples of Veterans

| Sampling Frame #1: National Survey | Sampling Frame #2: In-Depth Assessments | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics at Initial Wave | % or mean | N or SD | % or mean | N or SD |

| Age | 37 years | 9.5 | 39 years | 11.4 |

| Female gender | 15.5% | 134 | 22.7% | 45 |

| Race non-white | 27.2% | 236 | 64.7% | 130 |

| Education beyond high school | 82.3% | 713 | 72.2% | 143 |

| Army | 55.2% | 474 | 68.9% | 126 |

| Navy | 14.9% | 128 | 11.5% | 21 |

| Marines | 9.6% | 83 | 7.1% | 13 |

| Air Force | 20% | 171 | 12.0% | 22 |

| Coast Guard | 0.4% | 3 | 0.5% | 1 |

| Multiple Deployments | 26.5% | 230 | 26.2% | 48 |

| Reserves/National Guard | 48.4% | 420 | 56.3% | 103 |

| Unable to Meet All Basic Needs | 37.5% | 325 | 41.4% | 82 |

| Witnessed Others Wounded or Killed | 40.0% | 346 | 46.2% | 91 |

| Probable PTSD (DTS>48) | 17.9% | 155 | 28.7% | 49 |

| Probable PTSD + High Anger | 10.3% | 89 | 19.3% | 38 |

| Alcohol Misuse (AUDIT>7) | 24.3% | 211 | 31.4% | 62 |

| History of Violence or Arrests | 22.0% | 190 | 46.7% | 92 |

| Violent Behavior in Next Year | ||||

| Severe Violence | 8.8% | 76 | 14.0% | 27 |

| Other Physical Aggression | 25.9% | 224 | 47.2% | 91 |

| Any Violence or Aggression | 26.3% | 287 | 54.3% | 107 |

Note. Figures for the National Survey are based on a weighted sample size of n=866. In-depth assessments were not weighted and had a sample size of n=197.

Spearman correlations (Table 2) indicated statistically significant relationships (p<.05) between initial-wave risk factors (financial instability, combat experience, alcohol misuse, violence/arrests, and anger + PTSD) and violence. This pattern held for both levels of violence severity in both sampling frames, with few exceptions.

Table 2.

Spearman Correlations between Risk Factors at Initial Wave and Violence during Next Year in Both Sampling Frames

| National Survey | In-Depth Assessments | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factors at Initial Wave | Any Violence or Aggression in Next Year | Severe Violence in Next Year | Other Physical Aggression in Next Year | Any Violence or Aggression in Next Year | Severe Violence in Next Year | Other Physical Aggression in Next Year | ||||||

| Financial Instability | 0.2183 | <.0001 | 0.1764 | <.0001 | 0.2120 | <.0001 | 0.2592 | 0.0002 | 0.1269 | 0.0755 | 0.2416 | 0.0006 |

| Combat Experience | 0.2148 | <.0001 | 0.1608 | <.0001 | 0.2251 | <.0001 | 0.2774 | <.0001 | 0.0156 | 0.8274 | 0.2456 | 0.0005 |

| Alcohol Misuse | 0.1945 | <.0001 | 0.1569 | <.0001 | 0.1964 | <.0001 | 0.2472 | 0.0005 | 0.2116 | 0.0028 | 0.1765 | 0.0131 |

| Past Violence or Arrests | 0.3495 | <.0001 | 0.2488 | <.0001 | 0.3488 | <.0001 | 0.4091 | <.0001 | 0.3074 | <.0001 | 0.3173 | <.0001 |

| PTSD + Anger | 0.2493 | <.0001 | 0.2319 | <.0001 | 0.2866 | <.0001 | 0.2934 | <.0001 | 0.1793 | 0.0117 | 0.2850 | <.0001 |

Note. Please refer to methods as well as Figure 2 for calculation of individual items for risk factor scores.

Multiple regression analyses for the survey (Table 3) revealed that risk factors had significant associations (p<.05) with outcome variables, suggesting each risk factor contributed unique variance. Alcohol misuse showed a trend but not a significant association with severe violence. Summed total risk scores (as used in the screening tool) had significant associations with outcomes. AUC estimates in analyses for the survey ranged from .74 to .78.

Table 3.

Multiple Regression Analyses of Violence for National Survey

| Any Violence or Aggression in Next Year | Severe Violence in Next Year | Other Physical Aggression in Next Year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | OR | CI | P | |

| Individual Risk Factors at Initial Wave | |||||||||

| Financial Instability | 1.95 | 1.38–2.78 | 0.0002 | 2.22 | 1.32–3.73 | 0.0027 | 1.90 | 1.33–2.71 | 0.0004 |

| Combat Experience | 1.92 | 1.37–2.69 | 0.0002 | 2.03 | 1.20–3.46 | 0.0088 | 2.04 | 1.45–2.87 | <.0001 |

| Alcohol Misuse | 1.67 | 1.08–2.57 | 0.0216 | 1.69 | 0.94–3.04 | 0.0784 | 1.68 | 1.09–2.60 | 0.0198 |

| Past Violence or Arrests | 3.37 | 2.29–4.95 | <.0001 | 2.70 | 1.54–4.72 | 0.0005 | 3.36 | 2.28–4.94 | <.0001 |

| PTSD + Anger | 1.98 | 1.18–3.32 | 0.0095 | 2.20 | 1.19–4.07 | 0.0123 | 1.95 | 1.16–3.26 | 0.0116 |

| AUC=0.75, R2=.21, χ2=147.66, df=5, p<.0001 | AUC=0.78, R2=.18, χ2=77.43, df=5, p<.0001 | AUC=0.75, R2=.21, χ2=148.03, df=5, p<.0001 | |||||||

| Sum of Risk Items at Initial Wave | |||||||||

| Screen Total Score | 2.17 | 1.89–2.50 | <.0001 | 2.18 | 1.82–2.61 | <.0001 | 2.19 | 1.90–2.52 | <.0001 |

| AUC=0.74, R2=.20, χ2=141.67, df=1, p<.0001 | AUC=0.77, R2=.18, χ2=76.33, df=1, p<.0001 | AUC=0.74, R2=.21, χ2=142.43, df=1, p<.0001 | |||||||

Note. Please refer to methods as well as Figure 2 for calculation of individual items for risk factor scores.

Correspondingly, multiple regression analyses for in-depth assessments (Table 4) also showed that all risk factors had significant associations (p<.05) with outcome variables, except combat experience and alcohol misuse with respect to other physical aggression. As in the survey, total risk scores in the in-depth assessments had significant associations with outcomes. AUC estimates in analyses for in-depth assessments ranged from .74 to .80.

Table 4.

Multiple Regression Analyses of Violence for In-Depth Assessments

| Any Violence or Aggression in Next Year | Other Physical Aggression in Next Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p | |

| Individual Risk Factors at Initial Wave | ||||||

| Financial Instability | 1.96 | 1.00–3.81 | 0.0492 | 1.94 | 1.02–3.69 | 0.0448 |

| Combat Experience | 1.97 | 1.01–3.86 | 0.0480 | 1.80 | 0.95–3.39 | 0.0713 |

| Alcohol Misuse | 2.58 | 1.07–6.21 | 0.0342 | 1.53 | 0.70–3.31 | 0.2862 |

| Past Violence or Arrests | 3.82 | 1.95–7.49 | <.0001 | 2.40 | 1.26–4.57 | 0.0075 |

| PTSD + Anger | 3.11 | 1.13–8.55 | 0.0275 | 2.85 | 1.20–6.78 | 0.0182 |

| AUC=0.80 R2=.34, χ2=58.33, df=5, p<.0001 |

AUC=0.75 R2=.24, χ2=39.71, df=5, p<.0001 |

|||||

| Sum of Risk Items at Initial Wave | OR | CI | p | OR | CI | p |

| Screen Total Score | 2.55 | 1.91–3.42 | <.0001 | 2.05 | 1.59–2.65 | <.0001 |

| AUC=0.79 R2=.33, χ2=55.78, df=1, p<.0001 |

AUC=0.74 R2=.24, χ2=38.31, df=1, p<.0001 |

|||||

Note: For severe violence, individual risk factor analyses could not be conducted for the in-depth assessments as for the survey because there would be five predictors and only 27 instances of severe violence; such an analysis would produce an overfit model. However, the “screen total score” variable representing the sum of risk items could be appropriately analyzed with this data and was statistically significant, yielding an AUC=.74 for predicting severe violence using items from the risk screen found in Figure 2. statistically significant, yielding an AUC=.74 for predicting severe violence using items from the risk screen found in Figure 2.

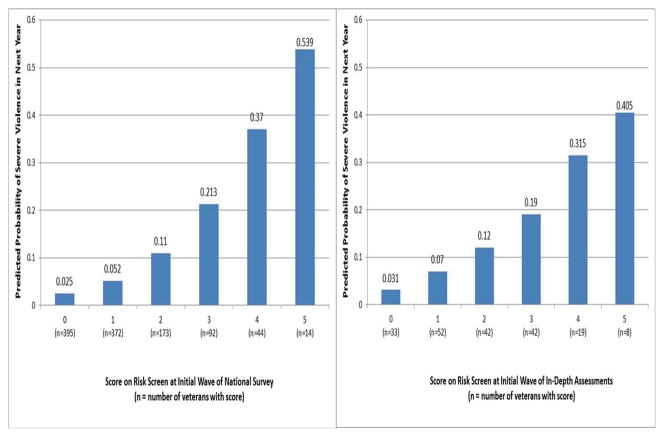

Predicted probabilities of severe violence in the next year are presented as a function of risk screen score at the initial wave (Figure 1). In support of the screen’s predictive validity, incidents of violence markedly increase at higher levels of predicted risk. To illustrate, in the survey, a score of “5” yielded a predicted probability of severe violence in the next year of 0.539, whereas a score of “0” yielded a predicted probability of 0.025, translating into a 95.3% (0.539–0.025/0.539) lower odds of severe violence between scores of “5” and “0.”

Figure 1.

Predicted Probability of Severe Violence in Next Year as a Function of Total Score on VIO-SCAN at Initial Wave in Both Sampling Frames of Veterans

Discussion

The current paper reports on the first evidence-based tool for assessing violence in military veterans, which we call the Violence Screening and Assessment of Needs (VIO-SCAN). The VIO-SCAN (Figure 2) offers potentially improved clinical decision-making and practice. First, the VIO-SCAN helps clinicians systematically gauge level of concern about veterans’ risk. Second, the screen helps clinicians judge not just individual factors but a combination of factors relevant for assessing risk. Third, the tool reduces stigma by demonstrating that PTSD alone does not lead to high risk of violence in veterans; instead, to elevate risk dramatically, PTSD must combine with other risk factors. Fourth, as three of the five factors are dynamic (anger + PTSD, alcohol misuse, and meeting basic needs), the VIO-SCAN can suggest interventions to reduce violence in veterans.

Figure 2. The Violence Screening and Assessment of Needs (VIO-SCAN) a.

aThe VIO-SCAN is not an actuarial tool or a complete risk assessment of violence. Instead, it provides a rapid procedure for 1) prompting clinicians to consider at least five empirically supported risk factors; 2) guiding clinicians to investigate individual or combinations of risk factors in greater detail to gauge level of clinical concern; 3) identifying veterans who may be at high risk of violence; 4) prioritizing referrals for a comprehensive violence risk assessment; and 5) assessing needs and dynamic factors to develop a plan to reduce risk. The VIO-SCAN should neither be used alone nor replace fully informed clinical decision making that investigates risk and protective factors beyond the five items in the screen. The screen does not designate whether a veteran is at low, medium, or high risk. Rather, the VIO-SCAN can structure a part of the evaluation of longer-term violence risk, not imminent danger. The screen does not have perfect accuracy, so false negatives and false positives will occur. A veteran with a score of 5 may never be violent, and one with a score of 0 may be violent. Please note that the VIO-SCAN needs to be replicated in other samples by other researchers and may be modified in the future as new research emerges.

As a caution, clinicians should not equate the brief assessment with a comprehensive risk assessment covering a host of other risk and protective factors. Moreover, false positives and false negatives will occur; clinicians should understand that high risk does not predict definite violence and low risk does not predict zero violence. Additionally, this screen does not replace informed clinical decision-making, which is necessary for properly interpreting results. Finally, clinicians should note that new research and scholarship indicate limits of actuarial models for violence risk assessment (43–45) and caution about relying too heavily on results, particularly high-risk findings.

Given its time frame, the VIO-SCAN is intended to estimate longer-term risk of violence providing for an assessment of chronic, as opposed to acute, risk. If clinicians are assessing need for immediate action or psychiatric hospitalization, it is critical to continue asking about current violent or homicidal ideation, intent, or plans. In these crisis situations, the screen can certainly help evaluate how serious a threat this individual poses in general; however, if a veteran endorses current homicidal ideation and plan but scores low on the VIO-SCAN, clinicians must recognize that the screen does not evaluate imminent danger as typically defined by civil commitment statutes.

Conversely, the screen may identify veterans not currently at acute risk but showing chronic risk. According to most civil commitment statutes, such individuals would not qualify for involuntary hospitalization. Instead, clinicians should recognize that outpatient veterans may require specific risk management or safety plans to reduce risk of future violence. Research documents that social, psychological, and physical well-being is associated with significantly reduced odds of violence in veterans, including those at higher risk (6). Consequently, rehabilitation targeting these areas of functioning, as well as PTSD, anger, financial health, and alcohol misuse, may be indicated for veterans scoring high on the VIO-SCAN.

Several psychometric limitations with the research should also be mentioned. Regarding external validity, although the VIO-SCAN was not based on veterans from previous eras of service, risk factors were selected from scientific literature on such veterans (7–11). Therefore, although research is needed to replicate these findings in other veteran samples, VIO-SCAN content is derived from the broader veteran population and is arguably relevant to all veterans. Future prospective research is needed to evaluate predictive validity of this violence risk screening tool; for example, examining clinicians’ use of the VIO-SCAN and determining its predictive validity in a VA or non-VA practice setting would be valuable.

Regarding internal validity, given that much of the data was gathered by self-report, underreporting is possible; however, rates of risk factors (e.g., PTSD, alcohol misuse) and violence generally comport with existing research on veterans (3, 4, 29, 46, 47). It was not possible to obtain criminal records, which might have revealed additional violence. However, studies show self and collateral reports cover most violent incidents in civilians (41), and veterans’ self-reported violence is related to arrest records for violent crimes (1, 26) .

To increase the likelihood of providers’ exploring critical veteran-specific risk factors, more research is needed to integrate violence risk assessment with veteran treatment. One model that may be of instructive value is the Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS), useful in suicide prevention among both civilian (48) and military samples (49). In CAMS, the primary methods of treatment engagement, assessment, treatment planning, progress tracking, and outcome evaluation are all conducted using evidence-based assessment tools that increase clinicians’ likelihood of asking about important but often-missed risk factors.

Similar approaches may fruitfully apply to violence risk in veterans. Within such a framework, violence risk management would not only include ongoing, evidence-based risk assessment, but would also give veterans opportunities to learn about and assess their own triggers. The current study suggests that most effective treatments target not a single condition but a constellation of risk factors. An ideal assessment tool would provide not only a score but also a shared language with which veterans and providers can discuss triggers during treatment, as well as better engaging veterans on a path toward recovery(6).

Violence toward others has been identified as a serious problem among military veterans. This study reports on the predictive validity of a brief screening tool (VIO-SCAN) for violence in veterans that can help clinicians structure risk assessment and identify potential avenues for reducing violence. At the same time, the VIO-SCAN does not replace fully informed clinical decision-making; instead, it provides a springboard for further research investigating risk and protective factors. More comprehensive civilian risk assessment measures such as the COVR and HCR-20 may also be considered, with the caveat of currently limited validation in veterans. Lastly, it is hoped that the VIO-SCAN will provide clinicians with a systematic method for identifying veterans at high risk, as well as an opportunity to develop plans collaboratively with veterans to reduce risk and increase successful reintegration in the community.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank all the veterans and military families who participated in this project. This study has not been published previously in an alternate form or in a government report. Preparation of this manuscript was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH080988), the Office of Research and Development Clinical Science and Health Services, Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Mid-Atlantic Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center, Office of Mental Health Services.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the National Institutes of Health.

Please note there are no financial conflicts of interest. The authors have no commercial interests in the results or products of this study.

References

- 1.MacManus D, Dean K, Jones M, Rona RJ, Greenberg N, Hull L, et al. Violent offending by UK military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: A data linkage cohort study. The Lancet. 2013;381(9870):907–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jakupcak M, Conybeare D, Phelps L, Hunt S, Holmes HA, Felker B, et al. Anger, hostility, and aggression among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans reporting PTSD and subthreshold PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20(6):945–54. doi: 10.1002/jts.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, McGurk D, Castro CA, Hoge CW. Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among Active Component and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):614–23. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sayer NA, Noorbaloochi S, Frazier P, Carlson K, Gravely A, Murdoch M. Reintegration problems and treatment interests among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans receiving VA medical care. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(6):589–97. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.6.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millikan AM, Bell MR, Gallaway MS, Lagana MT, Cox AL, Sweda MG. An Epidemiologic Investigation of Homicides at Fort Carson, Colorado: Summary of Findings. Military Medicine. 2012;177(4):404–11. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-11-00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elbogen EB, Johnson SC, Wagner HR, Newton VM, Timko C, Vasterling JJ, et al. Protective factors and risk modification of violence in Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(6):e767–73. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m07593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasko NB, Gurvits TV, Kuhne AA, Orr SP, et al. Aggression and its correlates in Vietnam veterans with and without chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1994;35(5):373–81. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(94)90278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orcutt HK, King LA, King DW. Male-Perpetrated Violence Among Vietnam Veteran Couples: Relationships with Veteran’s Early Life Characteristics, Trauma History, and PTSD Symptomatology. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16(4):381–90. doi: 10.1023/A:1024470103325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Savarese VW, Suvak MK, King LA, King DW. Relationships among alcohol use, hyperarousal, and marital abuse and violence in Vietnam veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14(4):717–32. doi: 10.1023/A:1013038021175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McFall M, Fontana A, Raskind M, Rosenheck R. Analysis of violent behavior in Vietnam combat veteran psychiatric inpatients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1999;12(3):501–17. doi: 10.1023/A:1024771121189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taft CT, Pless AP, Stalans LJ, Koenen KC, King LA, King DW. Risk Factors for Partner Violence Among a National Sample of Combat Veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):151–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elbogen EB, Fuller S, Johnson SC, Brooks S, Kinneer P, Calhoun PS, et al. Improving risk assessment of violence among military veterans: An evidence-based approach for clinical decision-making. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:595–607. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sreenivasan S, Garrick T, McGuire J, Smee DE, Dow D, Woehl D. Critical issues in Iraq/Afghanistan War Veterans-Forensic Interface Part 2:Nexus between Combat-related Post-deployment Criminal Violence and Use of a Post-deployment Criminal Violence Rating Guide. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. 2013;41:263–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson NV. Physician judgements of uncertainty. In: Chapman Gretchen B, Sonnenberg Frank A., editors. Decision making in health care: Theory, psychology, and applications. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grisso T, Tomkins AJ. Communicating violence risk assessments. American Psychologist. 1996;51(9):928–30. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hammond KR, Stewart TR. The essential brunswick: Beginnings, explications, applications: 2001. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2001. p. xii.p. 540. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monahan J, Steadman HJ. Violence and mental disorder: Developments in risk assessment: (1994) Chicago, IL, US: University of Chicago Press; 1994. p. x.p. 324. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otto R, Douglas K. Handbook of violence risk assessment tools. Milton Park, UK: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douglas KS, Cox DN, Webster CD. Violence risk assessment: Science and practice. Legal and Criminological Psychology. 1999;4(Part 2):149–84. [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNiel DE. Empirically based clinical evaluation and management of the potentially violent patient. In: Kleespies PM, editor. Emergencies in mental health practice: Evaluation and management. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. pp. 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Douglas KS, Skeem JL. Violence Risk Assessment: Getting Specific About Being Dynamic. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 2005;11(3):347–83. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Robbins PC, Appelbaum P, Banks S, Grisso T, et al. An Actuarial Model of Violence Risk Assessment for Persons With Mental Disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(7):810–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.7.810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardner W, Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Clinical versus actuarial predictions of violence in patients with mental illnesses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(3):602–9. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.3.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardner W, Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. A comparison of actuarial methods for identifying repetitively violent patients with mental illnesses. Law and Human Behavior. 1996;20(1):35–48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beckham JC, Moore SD, Reynolds V. Interpersonal hostility and violence in Vietnam combat veterans with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of theoretical models and empirical evidence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2000;5(5):451–66. [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacManus D, Dean K, Al Bakir M, Iversen AC, Hull L, Fahy T, et al. Violent behaviour in UK military personnel returning home after deployment. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42(8):1663–73. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM. Internet, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method. 3. New York: John Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vogt D, Vaughn R, Glickman ME, Schultz M, Drainoni M-L, Elwy R, et al. Gender differences in combat-related stressors and their association with postdeployment mental health in a nationally representative sample of U.S. OEF/OIF veterans. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0023452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanielian T, Jaycox L. Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corp; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beckham JC, Becker ME, Hamlett-Berry KW, Drury P, Kang HK, Wiley MT, et al. Preliminary findings from a clinical demonstration project for veterans returning from Iraq or Afghanistan. Military Medicine. 2008;173(5):448–51. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.5.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hotopf M, Hull L, Fear NT, Browne T, Horn O, Iversen A, et al. The health of UK military personnel who deployed to the 2003 Iraq war: A cohort study. The Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1731–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68662-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Johnson SC, Kineer P, Kang HK, Vasterling JJ, et al. Are Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using mental health services? New data from a national random sample survey. Psychiatric Services. 2013;64:134–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.004792011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehman AF. A Quality of Life Interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning. 1988;11(1):51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 34.King DW, King LA, Vogt DS. PTSD NCf, collab. Manual for the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI): A Collection of Measures for Studying Deployment Related Experiences of Military Veterans. Boston, MA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradley KA, Bush KR. Screening for problem drinking: comparison of CAGE and AUDIT. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1998;13(6):379–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00118.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davidson JRT, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, et al. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for posttraumatic stress disorder: The Davidson Trauma Scale. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:153–60. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonald SD, Beckham JC, Morey RA, Calhoun PS. The validity and diagnostic efficiency of the Davidson Trauma Scale in military veterans who have served since Sept 11th, 2001. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:247–55. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics Scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steadman HJ, Silver E, Monahan J, Appelbaum PS, Clark Robbins P, Mulvey EP, et al. A classification tree approach to the development of actuarial violence risk assessment tools. Law and Human Behavior. 2000;24(1):83–100. doi: 10.1023/a:1005478820425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elbogen EB, Johnson SC, Newton VM, Fuller SR, Wagner HR, Beckham JC. Self-Report and Longitudinal Predictors of Violence in Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2013;201(10):872–6. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182a6e76b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, Robbins PC, Appelbaum PS, Grisso T, et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55(5):393–401. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.5.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Center DMD. FY2009 Annual Demographic Profile of Military Members in the Department of Defense and US Coast Guard. Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute; 2010. Contract No.: Statistical Series Pamphlet No. 08–10. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hart SD, Cooke DJ. Another look at the (Im-)precision of individual risk estimates made using actuarial risk assessment instruments. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2013;31(1):81–102. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh JP, Grann M, Fazel S. Authorship Bias in Violence Risk Assessment? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e72484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fazel S, Singh JP, Doll H, Grann M. Use of risk assessment instruments to predict violence and antisocial behaviour in 73 samples involving 24,827 people: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2012;345(7868):1–12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burnett-Zeigler I, Ilgen M, Valenstein M, Zivin K, Gorman L, Blow A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol misuse among returning afghanistan and iraq veterans. Addictive Behaviors. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoge CW, Castro C, Messer S, McGurk D, Cotting D, Koffman R. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan: Mental health problems and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jobes DA, Wong SAAK. The collaborative assessment and management of suicidality vs. treatment as usual: a retrospective study with suicidal outpatients. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2005;(35):483–97. doi: 10.1521/suli.2005.35.5.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Comtois K, Jobes D, O-Connor S, Atkins D, Janis K, Chessen C, et al. Collaborative Assessment and Management of Suicidality (CAMS): Feasibility trial for next-day appointment services. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28:963–72. doi: 10.1002/da.20895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]