Abstract

Background

Like many viruses, bacteriophage ΦX174 packages its I)NA genome into a procapsid that is assembled from structural intermediates and scaffolding proteins. The procapsid contains the structural proteins F, G and H, as well as the scaffolding proteins B and D. Provirions are formed by packaging of DNA together with the small internal J proteins, while losing at least some of the B scaffolding proteins. Eventually, loss of the I) scaffolding proteins and the remaining B proteins leads to the formation of mature virions.

Results

ΦX174 108S 'procapsids' have been purified in milligram quantities by removing 114S (mature virion) and 70S (abortive capsid) particles from crude lysates by differential precipitation with polyethylene glycol. 132S 'provirions' were purified on sucrose gradients in the presence of EDTA. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) was used to obtain reconstructions of procapsids and provirions. Although these are very similar to each other, their structures differ greatly from that of the virion. The F and G proteins, whose atomic structures in virions were previously determined from X-ray crystallography, were fitted into the cryo-EM reconstructions. This showed that the pentamer of G proteins on each five-fold vertex changes its conformation only slightly during DNA packaging and maturation, whereas major tertiary and quaternary structural changes occur in the F protein. The procapsids and provirions were found to contain 120 copies of the I) protein arranged as tetramers on the twofold axes. IDNA might enter procapsids through one of the 30 Å diameter holes on the icosahedral three-fold axes.

Conclusions

Combining cryo-EM image reconstruction and X-ray crystallography has revealed the major conformational changes that can occur in viral assembly. The function of the scaffolding proteins may be, in part, to support weak interactions between the structural proteins in the procapsids and to cover surfaces that are subsequently required for subunit–subunit interaction in the virion. The structures presented here are, therefore, analogous to chaperone proteins complexed with folding intermediates of a substrate.

Keywords: cryo-electron microscopy, DNA packaging, icosahedral capsid, scaffolding proteins, viral assembly

Introduction

Like most DNA-containing phages, ΦX174 packages its single-stranded (ss) genome into a pre-formed protein shell, the 'procapsid' (traditionally called prohead by analogy with the tailed phages), during late stages of its assembly pathway. In general, procapsids are composed of viral structural proteins, plus scaffolding (or accessory) proteins that are not usually found in the mature virion [1–3].

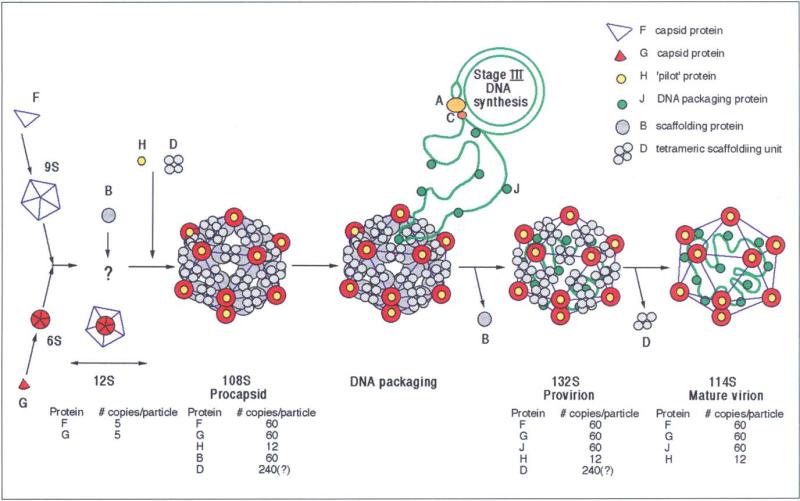

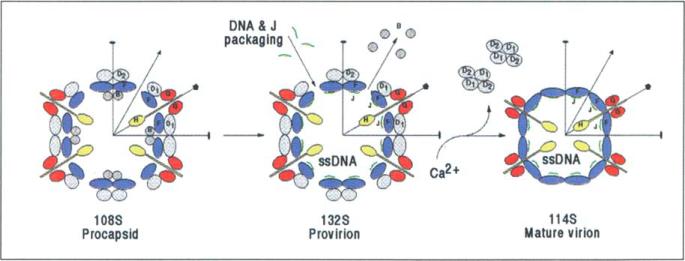

Several steps (Fig. 1; Table 1) have been enumerated in the assembly of ΦX174 [4]. Initially, the F and G proteins form 9S and 6S complexes, respectively, which are probably both pentamers on the basis of molecular weight estimates 51. Both types of pentamers then combine with the H protein and the B and D scaffolding proteins to form 108S procapsids which contain 60 copies each of F, G and B proteins, 12 copies of the H protein and 240 copies [6] (or as suggested here, only 120 copies) of the D protein. A 12S particle consisting of five copies each of the G and F proteins has been identified, but its participation in the assembly pathway is uncertain [7]. Aided by phage proteins A and C, the progeny ssDNA, along with 60 copies of the J protein, is packaged into procapsids, with the concurrent loss of the 60 copies of the B protein leading to the formation of 132S 'provirion' particles [8,9]. Conversion of these into 114S particles (mature virions) occurs in the final stage of morphogenesis and involves the loss of the D scaffolding proteins. This process may be triggered by higher levels of divalent cations present during cell lysis [10,11]. Either because of partial loss of DNA from the virion, or because of incomplete DNA packaging, 70S particles accumulate in the cell and represent a suicide end product [12–14].

Fig. 1.

Assembly pathway of ΦX174 based on Hayashi et al. [4].

Table 1.

Proteins involved in ϕX174 assembly.

| Protein | kDa | No. of amino acids | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| F | 48.4 | 426 | Major capsid protein; has virus structural β-barrel fold plus two large irregular insertions involved in monomer–monomer interactions. |

| G | 19.0 | 175 | Pentamers form 12 spikes on virion; has virus structural β-barrel motif. |

| J | 4.2 | 37 | Protein required for packing ssDNA into virion; has extended structure on internal face of the F protein in the virion. |

| H | 34.4 | 328* | 12 copies per virion; is disordered in X-ray studies; ‘pilot’ protein which enters E. coli during DNA injection. |

| B | 13.8 | 120* | Scaffolding protein used in formation of procapsid. |

| D | 16.9 | 152* | Scaffolding protein used in formation of procapsid; aggregates as a tetramer. |

Based on the DNA sequence.

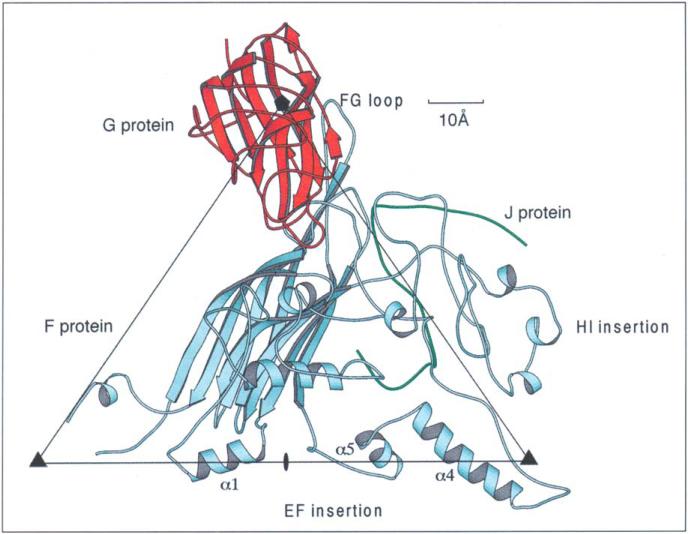

The crystal structure of the virion, previously determined to 3 Å resolution [15-17], showed the structure and capsid organization of the F, G andJ proteins in atomic detail. The capsid, with an average radial diameter of ~260 Å, consists primarily of 60 copies of the F protein arranged with icosahedral symmetry. The F protein adopts the β-barrel motif common to many virus structural proteins [18] (Fig. 2), and the β-strands run roughly tangential to the viral capsid surface. Two large loops, representing 65% of the F polypeptide chain, are inserted between the E and F and between the H and I strands and form the surface topology of the capsid. The 12 characteristic 70 Å wide 'spikes' that extend 30 Å above the F protein capsid surface are formed by pentameric aggregates of the G protein. The G protein also has the β-barrel motif, but the β-strands run roughly radial to the viral capsid surface and lack the insertion loops. The small DNA-packaging protein, J, is bound to the F protein on the interior surface of the capsid. Diffuse density observed in hydrophilic channels formed by the pentamers of G proteins may be attributable, in part, to the presence of the H protein.

Fig. 2.

The F (pale blue), G (red) and J (green) proteins in the virion as determined from the refined, 3 Å resolution, X-ray crystallographic structure [16] viewed down an icosahedral two-fold axis. Two-fold, three-fold and five-fold axes (indicated by an ellipse, two triangles and a pentagon, respectively) surrounding an icosahedral asymmetric unit are also shown.

Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and image reconstruction have been used to observe major rearrangements between empty proheads and virions for phage P22 [19] and phage γ [20]. No atomic models for the structural or scaffolding proteins of these phages exist to provide a more detailed description of the conformational changes required for maturation. Studies of negatively stained procapsids and provirions of ΦX174 [9] have shown that these particles are roughly spherical, with a diameter of ~400 Å. We report here the purification and cryo-EM reconstruction of the ΦX174 108S procapsid and 132S provirion, and the interpretation of the cryo-EM reconstructions in light of the known atomic [15] and cryo-EM [21] structures of the ΦX174 virion.

Results and discussion Purification and characterization

Previously, Mukai et al. [6] isolated procapsids by using a ΦX174 strain defective in the DNA-packaging gene C, which led to the accumulation of procapsids in the infected cells. However, in the present study it was observed that large numbers of procapsids and provirions, as well as mature virions, were present in extracts from a normal ΦX174 infection [22]. The procapsids could be recovered from the supernatant after removal of virions, provirions and 70S particles by precipitation with polyethylene glycol. Provirions could be isolated from the lysates by gradient centrifugation in the presence of EDTA (see the Materials and methods section).

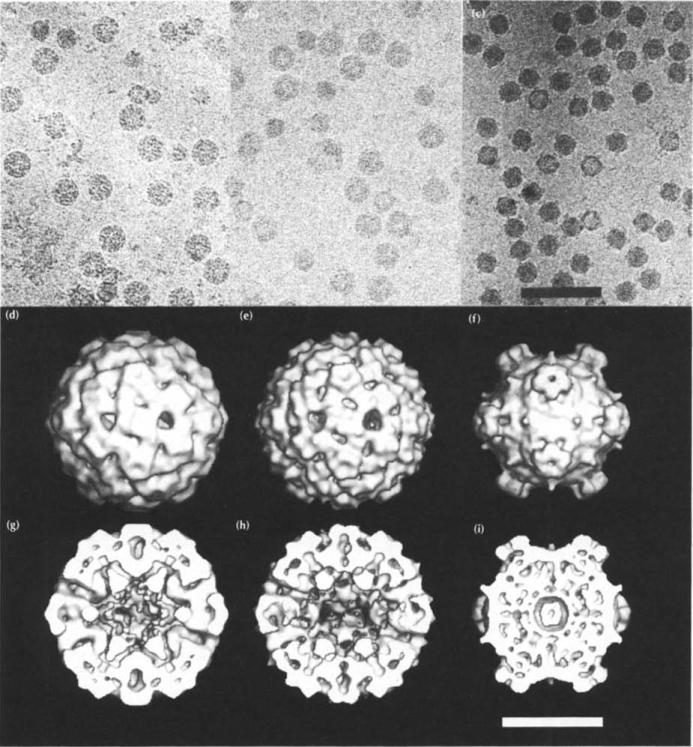

The ultraviolet spectrum for the procapsids had an A260/A280 ratio of 0.90±0.05, demonstrating that they contained little or no DNA, in contrast to the absorption ratio for virions (1.55±0.05) [14]. The absorption ratio for the provirions was 1.45±0.05, showing that they had gained DNA. By EM, procapsids and provirions are spherical, enabling them to be readily distinguished from virions with their characteristic morphology of spikes at the five-fold vertices (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cryo-electron micrographs and three-dimensional reconstructions of ΦX174 assembly particles. Images of frozen-hydrated particles (top row), shaded surface representations (center row) and cross-sections (bottom row) of each reconstruction are shown of the procapsid (a,d,g), the provirion (b,e,h) and the virion (c,f,i). The small particles in (a) and (b) are degraded procapsids and provirions that have lost the D scaffolding protein and are similar in structure to virions. The shaded surface representations and cross-sections are viewed down a two-fold axis. Spikes are observed along the periphery of the virions (f) and (i), but not on the procapsids, (d) and (g), or provirions, (e) and (h). The magnification bar corresponds to 1000 Å (a-c) and 200 Å (d-i).

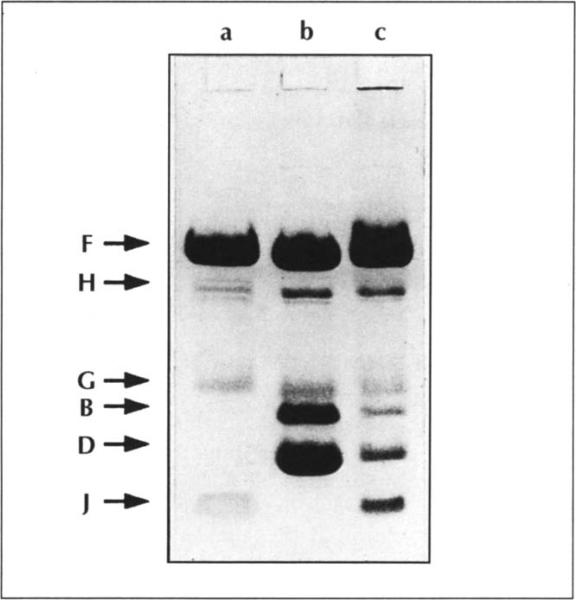

Analysis by SDS-PAGE revealed the presence of the F, G, H and J structural proteins in the virion (Fig. 4, lane a). Procapsid particles lacked the J protein and gave rise to two additional protein bands that migrated faster than G (Fig. 4, lane b), consistent with those previously observed for the B and D scaffolding proteins [6]. In contrast, the provirion particles contain the F, H, G, B, D and J proteins (Fig. 4, lane c). These provirions thus differ from the particles described by Mukai et al. [6] in that they contain at least some B protein (compare lanes b and c of Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

SDS-PAGE analysis of Φ1 74 particles. A 20% polyacryl-amide gel with 0.5% cross-linking agent was run in 0.75 M Tris-HCI (pH 9.3) buffer with 10% glycerol. The gel was loaded with virions in lane a, procapsids in lane b and provirions in lane c. Protein B migrates abnormally slowly under these conditions in an SDS gel [6].

Cryo-EM and three-dimensional reconstruction

Images of frozen hydrated samples of procapsids, provirions and virions (Fig. 3a–c) were used to produce three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions of the particles (Fig. 3d–i). The virion reconstruction (Fig. 3f, i) was previously published [21] and was shown to be consistent with the 3.0 Å atomic structure [15–17]. The excellent agreement between the EM density and the X-ray crystallographic structure (Fig. 5a) establishes the quality of the EM results. This justifies the assumption that the EM densities of the assembly intermediates are equally reliable and permits the interpretation of the image reconstruction in terms of atomic models. Nevertheless, some of the observed differences between the procapsid and provirion reconstructions may be attributable, in part, to the differences in resolution. The procapsid (Fig. 3d, g) and provirion (Fig. 3e, h) structures have very similar external morphologies, but both differ greatly in shape and size from the virion (compare with Fig. 3f, i). The subsequent description of the assembly intermediates will refer to the procapsid, unless it is explicitly necessary to differentiate between the procapsid and the provirion.

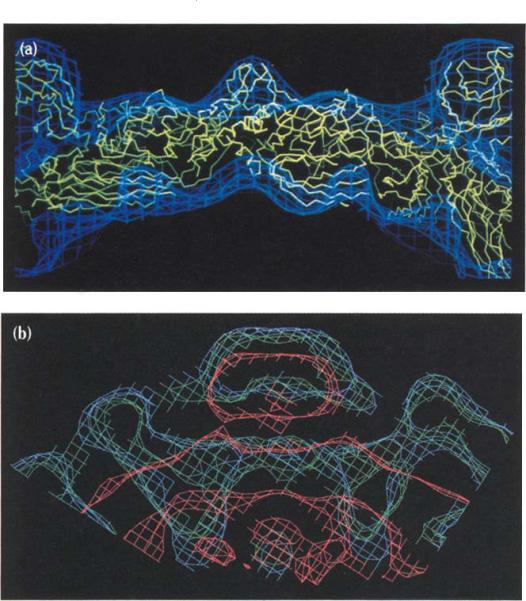

Fig. 5.

(a) Fit of the X-ray crystallographically determined atomic structure to the cryo-EM density of 70S particles (partially empty virions). An icosahedral three-fold axis runs vertically through the center of the figure. Notice the small spike made by helices α4 on the surface of the virus at the three-fold axis. (b) Compari-son of the procapsid (blue), provirion (green) and virion (red) cryo-EM densities viewed with the icosahedral five-fold axis running vertically through the center of the figure. The big spike of the virion on the five-fold axis is produced by G protein pentamers. The pentamer is condensed radially inwards by ~11 Å in the virion (red) relative to the assembly intermediates.

Both assembly intermediates are roughly spherical (363 Å maximum diameter), but their internal and external capsid diameters are larger than those of the virion (Table 2). The prominent five-fold spikes of the virion, giving these particles a maximum diameter of 335 Å, are present in the intermediates, but are masked by additional density on the particle surface. The presence of ssDNA in the virion contrasts with the empty procapsid (compare Fig. 3i with Fig. 3g). Somewhat surprisingly, the provirion particles also appear to be hollow and, therefore, devoid of DNA (Fig. 3h). However, the presence of DNA was established by A260/A280 measurements. Presumably, the larger internal cavity of the assembly intermediates (Table 2) allows looser packing of the DNA than in the virions. Another major difference between procapsid and virion is the presence of 30 Å diameter holes in the procapsid on the icosahedral three-fold axes. In virions, the same location is occupied by a minor protrusion at the surface (compare Fig. 3f with Fig. 3d, e).

Table 2.

Dimensions of ϕX174 particles.

| Diameter | Virion and 70S particle | Procapsid and provirion |

|---|---|---|

| External (along two-fold axis) | 247 Å | 363 Å |

| External (along three-fold axis) | 293 Å | – |

| External (along five-fold axis) | 335 Å | 355 Å |

| Internal volume | 5 × 106 Å3 | 13 × 106 Å3 |

Diameters are based on the cryo-EM reconstructions relative to an arbitrarily chosen density level.

This initial comparison of the image reconstructions shows that considerable structural rearrangements occur during capsid maturation, entailing entry of ssDNA andJ proteins as well as departure of the B and D scaffolding proteins. In order to understand these structural changes in more detail, a procapsid model was constructed by interactively fitting the F and G atomic structures of the virion into the procapsid EM density.

The absolute radial scale of the procapsid reconstruction was determined by comparison with virion-like particles in the same micrograph using a 3D density correlation procedure (see the Materials and methods section). The absolute hand of the reconstructions was tentatively established by fitting a truncated version of the F protein into the procapsid density (see below).

Modeling of the G protein

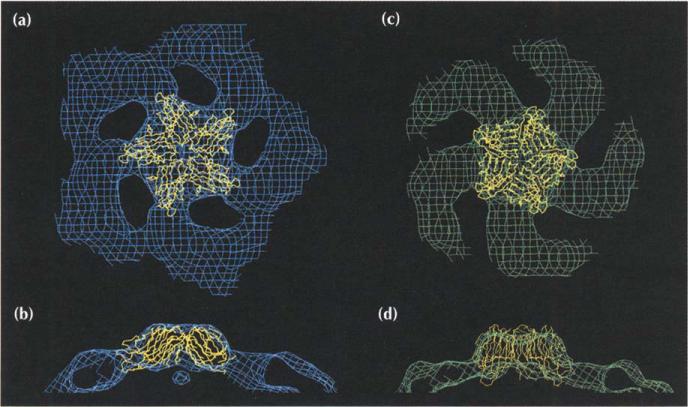

The G pentamer spikes are present on the procapsid, although they are less obvious than on the virion. The whole pentamer is translated radially outwards by 11 Å (Fig. 5b). In the procapsid, but not the provirion, a further 20° rotation of the entire pentamer about the five-fold axis gave an equally good fit (Table 3; Fig. 6). In virions, the edges of the spike are composed of antiparallel β-strands that lie roughly parallel to the five-fold axis. In the procapsid, but not in the provirion, the edges of the spike are inclined by ~20° to the five-fold axis. This suggests that the G protein β-barrel tilts outwards at lower radius, thus widening the base of the pentamer (Fig. 6b). The β-barrel of the G protein structure as found in the virion fits nicely into the procapsid density map, but the extended N and C termini (10 residues each) fall outside the density.

Table 3.

Agreement between model and map.

| Model | EM map (hand) | Coordinatesa | Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Virion (+) | X-ray | 0.93 |

| 2 | Virion (–) | X-ray | 0.86 |

| 3 | Procapsid (+) | X-ray | 0.58 |

| 4 | Procapsid (–) | X-ray | 0.31 |

| 5 | Procapsid (+) | F+, Grot | 0.93 |

| 6 | Procapsid (+) | F+, Gunrot | 0.93 |

| 7 | Procapsid (–) | F+, Grot | 0.74 |

| 8 | Procapsid (–) | F–, Grot | 0.91 |

| 9 | Procapsid (–) | F–, Gunrot | 0.91 |

| 10 | Provirion (+) | F+, Grot | 0.88 |

| 11 | Provirion (+) | F+, Gunrot | 0.90 |

| 12b | Procapsid (+) | Procapsid (–) | 0.69 |

| 13 | Virion (+) | Virion (–) | 0.95 |

X-ray refers to the X-ray crystallographic coordinates for the whole of the F and C proteins. F+ refers to the truncated model of the F protein as fitted into the procapsid (+) map. F– refers to the truncated model of the F protein as fitted into the procapsid (–) map. Gunrot refers to the truncated model of the G protein in the same orientation as found in the virion. Grot refers to the truncated model of the G protein rotated by 20° from the virion orientation.

Correlation between maps of opposite hand. This demonstrates that the procapsid map has greater ‘handedness’ than that of the virion.

Fig 6.

Fit of the G protein pentamer into cryo-EM density. The procapsid density is shown in (a) and (b) with the truncated G pentamer rotated by 20° relative to its orientation in the virion. The unrotated G pentamer is shown fitted into the provirion EM density in (c) and (d). Electron densities are color coded as described for Fig. 5b. The models show connected Ca-atoms in yellow. The views are from outside the virus looking down a five-fold axis (a,c) and with the five-fold axis vertical (b,d).

Contact between the G pentamer and the underlying shell of the F capsid protein in the virion is mediated by at least 25 solvent molecules [16], suggesting that the G pentamer 'floats' above a crater formed by five F proteins. In the procapsid, this interface forms a striking gap of 30 Å width (Fig. 5b). The main contact of the G protein pentamer with the rest of the procapsid structure is made with the D scaffold proteins (see below).

Modeling of the F protein

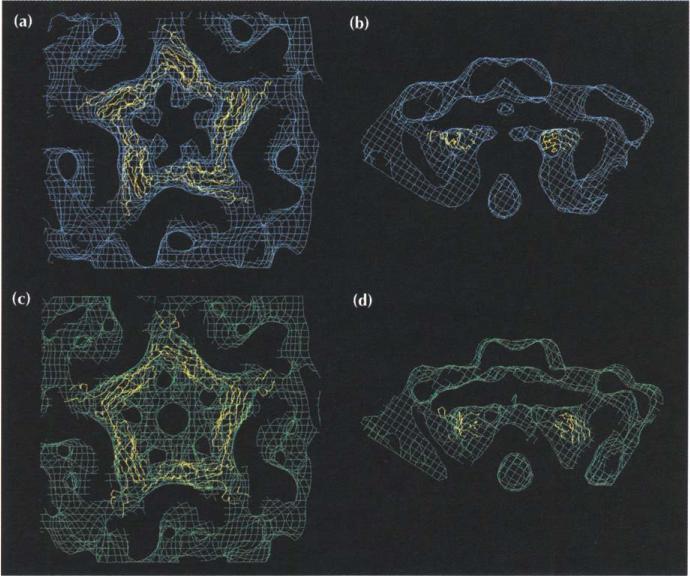

Compared with the G protein, fitting of the virion's F protein structure into the procapsid and provirion density maps was more difficult. The main axis of the F protein β-barrel in the virion points in a tangential direction towards the five-fold axis, where the FG loops of all five F monomers contact each other as well as the overlying G proteins. In contrast, a ~30 Å diameter hole is found at the center of the F protein pentamer of the procapsid (Fig. 7a, c). The F protein β-barrel has two large insertions, one of 163 residues between β-strands E and F and the other of 111 residues between β-strands H and I. The -barrels within a pentamer in the virions make few contacts, but most of the interactions occur between the EF insertion of one subunit and the HI insertion of the five-fold-related neighboring subunit. Procapsids and provirions have a 30 Å diameter hole on each three-fold axis, which is exactly where part of the EF insertion makes contact in the virion (Fig. 3).

Fig. 7.

Fit of the F protein pentamer into cryo-EM density of the procapsid (a) and (b) and provirion (c) and (d), color coded as described for Fig. 5b. The views are down a five-fold axis (a,c) and from the side (b,d). Only the truncated F protein is shown, that is the β-barrel without the EF and HI insertions.

Conformational changes in the F protein were assumed to occur mostly in the insertion loops, thus leaving the core β-barrel domain unchanged during maturation. Consequently, these insertion loops were removed from the F protein model prior to fitting it into the EM density. A good fit was obtained when the β-barrel was rotated by almost 90° about an approximately radial axis (Fig. 7; Table 3). An alternative but poorer fit was obtained when the F protein was rotated ~45° in the opposite direction (data not shown) and fitted into the map of the opposite hand. Although the second model gave a poorer fit, the F protein required smaller changes in position and orientation relative to the virion (Table 3). In both models, the ring of five contiguous F subunits lies within a shell of ~25 Å thickness, compared with 45 Å in the virion. This change in shell thickness is attributable to the conformational change of the insertion loops.

The provirion and procapsid structures exhibit similar features (Fig. 3). However, the F proteins of the provirion are tilted slightly relative to their orientation in the procapsid so that they are positioned more similarly to those in the virion (Table 4). Thus, the F protein may adopt an orientation in the provirion that represents an intermediate state in the maturation of virions from procapsids.

Table 4.

Orientational and translational differences between models.

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Rotation (°)b | Translation (Å)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virion G | Procapsid Gunrot | 0 | 11 |

| Virion C | Procapsid Grot | 20 | 11 |

| Virion F | Procapsid F+ | 77 | 19 |

| Virion F | Procapsid F– | 40 | 14 |

| Procapsid Gunrot | Provirion Gunrot | 0 | 0 |

| Procapsid Grot | Provirion Grot | 20 | 0 |

| Virion F | Provirion F+ | 77 | 14 |

See Table 3 for definition of G, Grot, Gunrot, F– and F+ models.

Rotation is anticlockwise, when the virus is viewed from the outside, for generating Model 2 from Model 1.

Translation is the increased radial distance in generating Model 2 from Model 1.

It is impossible to assign specific density to the insertion loops in a 26 Å resolution electron-density map, especially when dramatic conformational changes have occurred. However, there is additional unassigned density in the procapsid reconstruction that protrudes from the F protein β-barrel domain where the insertion loops enter and exit the β-barrel. At the EF insertion, density extends to the surface where it contacts features that have been ascribed to one of the D proteins (see below). The HI insertion is positioned near U-shaped density at the two-fold axes (Fig. 8). The provirion shares all of these features with the procapsid, but also has an additional ring of density around the five-fold axis at a particle radius of 122 Å (Fig. 7c).

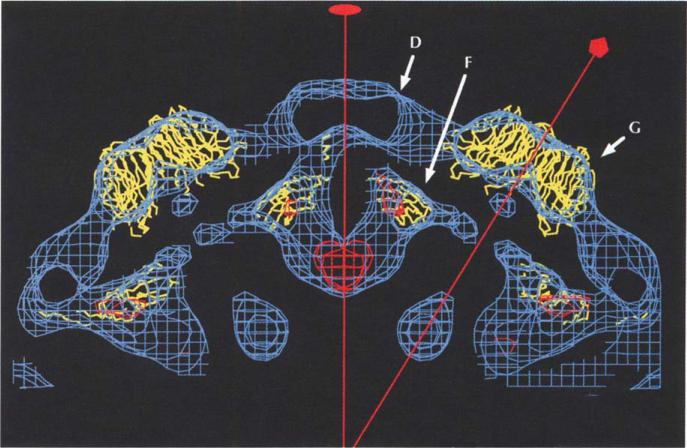

Fig. 8.

Cryo-EM density (blue) of the procapsid with an icosahedral two-fold axis vertical. The difference map of the procapsid minus the provirion cryo-EM density (in red), shows the presence of the B scaffolding protein on the two-fold axis. G pentamer and F pentamer structures are shown on either side of the two-fold axis. Note the additional density outside the F capsid proteins, which has been assigned to the D scaffolding proteins.

The small protrusions on the three-fold axes of virions (Fig. 3) are formed by helix α4 in the EF insertion of each of the three-fold-related F subunits. In contrast, procapsids and provirions have 30 Å diameter holes on the three-fold axes. In addition, helices αl and α5 in the EF insertion form F subunit interactions across icosahedral two-fold axes in the virion (Fig. 2), but at this site in the procapsid a gap (Fig. 8) lies immediately below the proposed sites of the D scaffolding proteins (see below). The contacts between F subunits are, therefore, completely different in virions and assembly intermediates. Furthermore, the two major β-barrel insertions must undergo considerable conformational changes during the maturation process.

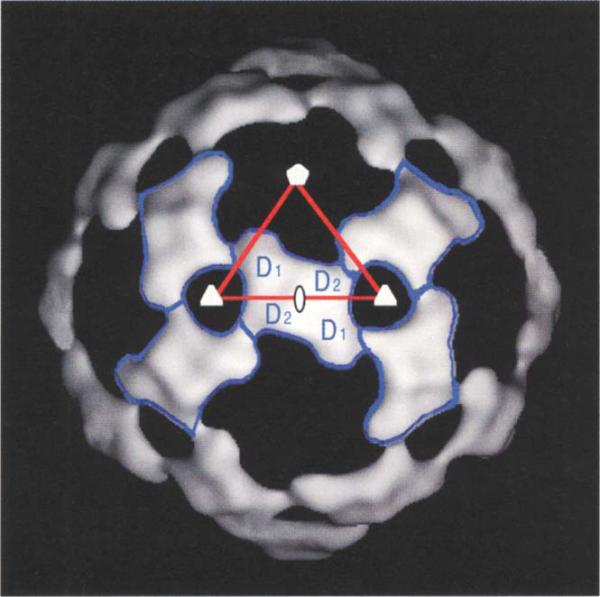

The D protein scaffold

Previous estimates of the number of copies of protein D per capsid have ranged from 80 [11] to 240 [6], and it is known that D can aggregate into tetramers in solution [23]. The modeling of the G and F proteins leaves uninterpreted densities centered about the two-fold axes on and below the surface of the procapsid and provirion. The uninterpreted external densities have a morphology that is consistent with a tetramer situated on the icosahedral two-fold axes (Fig. 9). This density has been ascribed to the D scaffolding proteins, with a total of 120 copies per capsid. This interpretation is consistent with volume measurements calculated from the reconstructions. Each D tetramer contacts two G pentamers, two underlying F protein β-barrels and four adjacent D tetramers. The putative D tetramer is a dimer of dimers, (D1D2)2, because D1 and D2 have different environments (Fig. 9). Each D1D2 dimer contacts a two-fold-related dimer via interactions between the D) subunits across an icosahedral two-fold axis. By themselves, the D tetramers form an external skeleton with contacts between D1 of one tetramer and D2 of another. The D1 monomers also provide support for the G pentamer, while the D2 monomers internally tether the F pentamers. This unusual arrangement of 120 copies of D protein per capsid is not unique. Several double-stranded RNA viruses such as the fungal viruses L-A and P4 [24], the reoviruses [25] and phage Φ6 ([26]; T Dokland, S Butcher, L Mindich, SD Fuller & DH Bamford, personal communication) have been shown to have capsids comprising 120 copies of at least one protein subunit.

There is a mutation in the D protein that leads to the formation of unstable procapsids at 24°C. Fane et al. [27] isolated seven different mutations that suppress the phenotype of this primary cold-sensitive (cs) mutation. In addition, several of these suppressor mutations also suppress the cs phenotype of a primary mutation at another amino acid 10 residues away in the D polypeptide chain. It may be no coincidence that five out of seven of the suppressor mutations map to the EF insertion of the F protein and that this insertion could contact the D2 scaffolding protein subunits. Another suppressor mutant maps to the J protein, which is bound to the EF and HI insertions in the virion, and may exert its effect in a similar fashion.

The B protein

The difference between the procapsids and provirions as characterized by Hayashi et al. [4] is that the provirions lack the B scaffolding protein, but have gained DNA and J proteins. After assigning densities to the F, G and D proteins, a U-shaped density on the two-fold axis remained unassigned. This position corresponded to the most prominent feature in a difference map in which the provirion density was subtracted from the procapsid density (Fig. 8). Part of the U-shaped density could be accounted for by the HI insertion of the F protein. The remaining density is consistent with its assignment to the B scaffolding protein, although its volume is not large enough for two B subunits. These results suggest that the provirions characterized here still contain some B scaffolding protein, whereas the 132S particles of Mukai et al. [6] are likely to be later intermediates that are devoid of all B protein.

The H protein

Procapsids and provirions also have an apparently disconnected density on each five-fold axis below the G pentamer at a smaller radius than the F pentamer (Figs. 3, 5, 8). Similar density, although somewhat weaker than the rest of the capsid, occurs in the EM reconstruction of the virion. All structural proteins (G, F and J), other than H, were assigned crystallographically in the virion [15]. Hence, the densities on the five-fold axes in the virion are either the H proteins or some ordered DNA. In the procapsid, the G, F, D and B proteins have been assigned, leaving only the H protein unassigned. Thus, the H protein probably accounts for the unassigned densities on the five-fold axes of all three particles. Such an assignment is consistent with, firstly, the H protein being ejected with the DNA during infection of E. coli [28], secondly, EM data showing that DNA is ejected out of the pentameric spikes [29], and thirdly, there being only 12 copies of the H protein per virion.

The lack of contact of this putative H protein density with the rest of the capsid and its relatively small size in comparison with its expected molecular weight may be accounted for by smearing during the icosahedral averaging process. The X-ray crystallographic results on the virion showed no interpretable electron density that could be confidently ascribed to the H protein, with the possible exception of some low density in the channel along the axis of the G pentamer spikes. The H protein is probably disordered, because of the high proportion of glycine and proline residues it contains [30], but the lack of interpretable density may just be a consequence of the icosahedral symmetry. Monoclonal antibodies that bind to SDS-denatured H protein cross-react with virions and procapsids (NL Incardona, unpublished data) suggesting that a portion of the H protein may extend out of the hydrophilic channel at the five-fold axes of the virion and assembly intermediates.

Conclusions

Here we have presented the 3D structures of two stable intermediates in the assembly pathway to formation of 4X174 virions (Fig. 10) — the empty procapsid and the provirion containing the genomic ssDNA.

According to the model of Hayashi et al. [4], the assembly process starts with the formation of pentamers of the G and F proteins. Siden and Hayashi [7] describe a 12S particle, consisting of a complex of one F and one G pentamer, as a possible intermediate in assembly. It is shown here that the G pentamer remains essentially intact from the procapsid to the virion stage and probably corresponds to the structure of the G pentamer seen by Hayashi and co-workers in solution. The structure of the F pentamer, on the other hand, differs greatly between the procapsid/provirion stage and the virion. The assignment of the scaffolding protein B to the two-fold axes, and the almost complete absence of contacts between F and G pentamers in the procapsid, are inconsistent with the 12S particle as an assembly intermediate. The role of the B protein appears to be to hold the F pentamers together across icosahedral two-fold axes.

In the absence of D or B scaffolding proteins, pentamers of F and G are still formed but no shell is assembled [5]. The role of these two scaffolding proteins in assembly may be, therefore, to bring pentamers together and hold the procapsid shell as a stable intermediate. The role played by the scaffolding proteins is analogous to the function of chaperones in facilitating the folding of polypeptide chains into their final, stable, tertiary conformation. Thus, the present structures represent folding intermediates complexed with chaperone-like proteins.

The large holes on the three-fold axes of the procapsid may provide potential portals for entry of a loop of antiparallel, single-stranded, circular DNA as it is packaged during replication. Such a loop would be dsDNA, which has a diameter of ~20 Å, and would, therefore, fit through any of these holes quite easily. The basic J proteins probably bind to the DNA and neutralize the negative charges of the phosphates. The B proteins would need to exit from the procapsid through any of the remaining 19 portals during the DNA packaging process.

At some point after DNA entry, the DNA-containing provirion condenses to form the virion. This transformation is a consequence of the removal of the D protein and is probably induced by an increase in Ca2+ concentration upon host cell lysis [10,11]. ΦX174 recognizes a lipopolysaccharide receptor on the outer cell membrane of E. coli [31–34]. In the virion, a putative carbohydrate site (associated with the EF insertion of the F protein) is generated by binding of two Ca 2+ ions [35]. Thus, the D scaffolding protein protects against premature ejection of DNA by inhibiting formation of the receptor attachment site. As Ca2+ is known to release the D protein, it would, therefore, permit the formation of the receptor-binding site and, thus, generate the virion.

Biological implications

The assembly of virions from the component proteins, nucleic acid and other molecules usually proceeds through a series of intermediates (often involving transient association with scaffolding proteins) to the final infectious particles. The three-dimensional structures of two such intermediates in the pathway to formation of ΦX174 viri-ons – the empty procapsid and the provirion containing the single-stranded (ss) genomic DNA – re presented here. By combining cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and crystallography, a more detailed picture of such assembly intermediates has been obtained than was previously possible. Techniques are presented for isolating and stabilizing milligram quantities of the intermediates. Similar techniques could be readily adaptable to other viral systems.

The changing relationship between the structural proteins that occurs in the assembly and maturation of ΦX174 has been elucidated by comparing the EM reconstructions of the procapsid and provirion with the X-ray structure of the virion. Pentamers of the G protein that form spikes in the virion have a similar conformation in both of the assembly intermediates and in the virion. However, the F capsid proteins undergo major conformational changes and rearrangements during assembly. Direct contact between the G pentamers and the underlying F proteins is minimal in the precursor capsids. Instead, tetramers of the external D scaffolding protein form an icosahedral cage that tethers the G pentamers on the outside to the pentameric rings of F proteins on the inside. The internal B scaffolding proteins appear to hold the F proteins together across the two-fold axes. The role of the scaffolding proteins in facilitating the folding and assembly of polypeptide chains into the final virion structure is therefore analogous to that played by chaperones.

Small conformational changes in proteins frequently occur in enzymes during catalysis [36,37]. However, the larger scale conformational changes observed here are not unique. Virus maturation in the dsDNA bacteriophages P22 [19] and γ [20], during which the procapsids expand in size rather than contract as in the case of ΦX174, also involves major structural rearrangements. Other examples of major conformational changes include the rearrangement of bacteriophage T4 baseplates [38]; assembly of T4 polyheads [39]; movements of muscle proteins such as myosin during the contraction cycle [40]; the insertion of colicin into membranes [41]; and membrane fusion by influenza virus [42]. Recently, crystals of d4X174 procapsids have been obtained that diffract to 3.5 A resolution, promising to provide atomic resolution detail of the assembly and folding processes described here.

Materials and methods

Materials, plaque assay, growth of ΦX174 and biochemical method

A detailed description of E. coli C and HF4714, the amber non-suppressor and suppressor strains, the tryptone-yeast extract (TYE) medium and borate buffer were reported in a previous publication [43]. The procedures for growing and assaying the infectivity of ΦX174 Eam3 [22] were the same as those previously described [43], except that the CaC12 concentration during the log phase growth of the cells was increased to 8.5 mM. A second addition of CaCl2 (final concentration 8.5 mM) was also made prior to infection with the phage.

The protein composition was determined with polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) [44]. A separating gel of 20% (w/v) total acryl-amide with 0.5% cross-linking agent and 10% (w/v) glycerol (pH 9.3) was used [45].

Purification of procapsids and provirions

One liter of E. coli cells was lysed by the addition of 10 mg lysozyme and three cycles of freezing/thawing [46]. Debris was removed by centrifugation at 16 000 g for 15 min, upon which the DNA-containing ΦX174 particles were precipitated by addition of 5 g of polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 (Fisher brand Carbowax) per 100 ml lysate and stirring the solution overnight at 4°C. After centrifugation at 16 00 0 g for 20 min to remove the precipitate, the procapsids in solution were pelleted by centrifugation for 1.5 h at 226 000 g at 5°C in a 50Ti rotor. The pellets were resuspended in 5% (w/v) potassium tartrate in pH 9.1 borate (final pH of 9.4). The insoluble material was removed by centrifugation in an Eppendorf microfuge for 2 min. The final step of purification was rate-zonal centrifugation at 5°C and 240000 g for 30 min in a VTi50 rotor, or 141000 g for 4 h in a SW28 rotor. The gradient was either a 5–25% (w/w) sucrose gradient in a 5% potassium tartrate/borate buffer or a 10–40% (w/v) potassium tartrate gradient in pH 9.1 borate buffer. A turbid band in the center of the final sucrose or tartrate gradient marked the location of the procapsids, consistent with the results of Mukai et al. [6]. If the procapsid-containing fractions were dialyzed for 3 days against the sodium tetrabo-rate buffer commonly used for storage of virions, the particles dissociated. However, if the fractions were not dialyzed, thereby retaining the potassium tartrate, the particles remained stable for at least 3 months at 5°C.

Provirions were obtained from cells lysed in the presence of high concentrations of EDTA (lysis buffer containing 10 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM NaCI, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.2). After removal of insoluble material from the crude lysate by centrifugation at 16000 g for 15 min, the supernatant was centrifuged for 1.5 h at 302000 g at 5°C in a 50.2Ti rotor. The resulting pellets were resuspended in 4 ml of 10 mM Tris-Cl, 250 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, pH 7.5 and layered onto a 5–25% (w/w) sucrose gradient in the above buffer. The centrifugation was performed in a SW28 rotor at 141 000 g for 4 h at 5°C, resulting in three clearly separated bands. The band nearest the bottom of the tube contained the provirions, while the middle and top bands contained virions and 70S particles, respectively. Stabilization of the provirion over a longer time required the addition of saturated EDTA to keep free divalent cations out of solution.

Cryo-electron microscopy and image reconstruction

The cryo-EM and image processing procedures used to obtain the three-dimensional reconstructions of procapsids and provirions have been described previously [47–49]. Samples were examined on a Philips EM420 transmission electron microscope and were maintained at near liquid nitrogen temperature in a Gatan 626 cryotransfer stage. The micrographs chosen for image processing were recorded under minimal dose conditions (~20e− Å−2), at an instrument magnification setting of 49 000× and at 80kV accelerating voltage. The objective lens defocus was 1.4 μm and 1.1 μm for the procapsid and provirion micrographs, respectively. The phase origins (particle centers) of the procapsid particle images were initially determined by cross-correlation against a circularly symmetrized average of all the images of the data set. The orientation parameters for each image were determined with common-lines and cross common-lines techniques [47,50,51]. The phase origins and orientation parameters were iteratively refined until a 143 particle data set was obtained and a three-dimensional reconstruction calculated that had an effective resolution of ~26 Å. The orientations and phase origins of the provirion particle images were determined by use of a model-based approach which utilized a reconstruction of the procapsid as the starting model [48,52]. A final three-dimensional reconstruction, derived from 142 particle images, was calculated to an effective resolution of −20 A. Separate and independent data sets from both the procapsid and provirion sets were compared to determine the effective resolution of each reconstruction as previously described [53].

Modeling

Full icosahedral symmetry was applied to the EM reconstruction maps by real-space interpolation. The X-ray coordinates of the ΦX174 virion [15] were fitted interactively into the reconstruction density using the program 'O' [54]. As the absolute hand of the reconstructions was not known, fitting was attempted in both possible enantiomers.

Electron-density maps were calculated from coordinates by summing the atomic numbers of the atoms assigned to a particular grid point on a 5 Å grid [55] and low pass-filtering this map to 20 Å resolution. These maps were compared with the EM density maps to check the quality of the fit. An estimate of the quality of the fit was given by the correlation coefficient (CC):

where pl and p2 represent the EM and calculated maps, respectively.

Difference maps were generated by normalizing the densities of the two maps to a given mean and standard deviation, then radially scaling them before subtracting one map from the other.

To estimate the molecular mass and, hence, the number of copies of proteins, the volume of the pixels whose densities were above a certain cutoff level was measured in the vinrion map. A cutoff level was determined that gave a volume corresponding to the known mass of the virion based on a protein density of 1.23 Å3 Da−1. The cutoff level determined in this way was applied to the procapsid and also to the provision map. This yielded a mass estimate for these particles. These estimates were cross-checked by using the volume of the G protein in the virion map as a standard.

Cα coordinates of the truncated F protein and of the G protein as modeled into the procapsid have been submitted to the Brookhaven Protein Data Bank.

Fig. 9.

An asymmetric unit (red) has been superimposed on the surface density of the procapsid after subtracting all but the putative D protein density. The position of the D tetramer (D1D2)2 is indicated in blue outline, illustrating the differing environments for the D1 and D2 monomers. The D tetramers form a cohesive scaffolding by themselves that serves to stabilize the procapsid prior to DNA insertion.

Fig. 10.

Diagrammatic representation of the protein organization in the procapsid, provirion and virion.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to G Wang for examining negatively stained procapsid samples. The work was supported by National Science Foundation grants to MGR and TSB, a National Institutes of Health grant to TSB, the Robert and Richard Rizzo Memorial Fund to NLI, and a European Molecular Biology Organization postdoctoral fellowship to TD. A Lucille P Markey Foundation Award to MGR provided additional facilities at Purdue University.

References

- 1.Kellenberger E. Form determination of the heads of bacteriophages. Eur. 1. Biochem. 1990;190:233–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murialdo H, Becker A. Head morphogenesis of complex double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid bacteriophages. Microbiol. Rev. 1978;42:529–576. doi: 10.1128/mr.42.3.529-576.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hendrix RW, Garcea RL. Capsid assembly of dsDNA viruses. Sem. Virol. 1994;5:15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayashi M, Aoyama A, Richardson DL, Jr., Hayashi MN. Biology of the bacteriophage ϕX174. In: Calendar R, editor. In The Bacteriophages. Vol. 2. Plenum Press; New York and London: 1988. pp. 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tonegawa S, Hayashi M. Intermediates in the assembly of ϕX174. J. Mol. Biol. 1970;48:219–242. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukai R, Hamatake RK, Hayashi M. Isolation and identification of bacteriophage ϕX174 prohead. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:4877–4881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.4877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siden EJ, Hayashi M. Role of the gene B product in bacteriophage ϕX174 development. J. Mol. Biol. 1974;89:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aoyama A, Hamatake RK, Hayashi M. Morphogenesis of ϕX174: in vitro synthesis of infectious phage from purified viral components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:7285–7289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujisawa H, Hayashi M. Assembly of bacteriophage ϕX174: identification of a virion capsid precursor and proposal of a model for the functions of bacteriophage gene products during morphogenesis. J. Virol. 1977;24:303–313. doi: 10.1128/jvi.24.1.303-313.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujisawa H, Hayashi M. Two infectious forms of bacteriophage ϕX174. Virol. 1977;23:439–442. doi: 10.1128/jvi.23.2.439-442.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weisbeek PJ, Sinsheimer RL. A DNA-protein complex involved in bacteriophage ϕX174 particle formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1974;71:3054–3058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.8.3054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisbeek PJ, Van de Pol JH, Van Arkel GA. Genetic characterization of the DNA of the bacteriophage ϕX174 705 particle. Virology. 1972;48:456–462. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinsheimer RL. Purification and properties of bacteriophage ϕX174. Mol. Biol. 1959;1:37–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(63)80017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eigner J, Stouthamer AH, van der Sluys I, Cohen JA. A study of the 70S component of bacteriophage ϕX174. Mol. Biol. 1963;6:61–84. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McKenna R, et al. Incardona NL. Atomic structure of single-stranded DNA bacteriophage ϕX174 and its functional implications. Nature. 1992;355:137–143. doi: 10.1038/355137a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKenna R, lag LL, Rossmann MG. Analysis of the single-stranded DNA bacteriophage ϕX174, refined at a resolution of 3.0 Å. Mol. Biol. 1994;237:517–543. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McKenna R, Xia D, Willingmann P, Ilag LL, Rossmann MG. Structure determination of the bacteriophage ϕX174. Acta Crystallogr. B. 1992;48:499–511. doi: 10.1107/s0108768192001344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossmann MG, Johnson JE. Icosahedral RNA virus structure. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1989;58:533–573. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.58.070189.002533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prasad BVV, et al. Chiu W. Three-dimensional transformation of capsids associated with genome packaging in a bacterial virus. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;231:65–74. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dokland T, Murialdo H. Structural transitions during maturation of bacteriophage lambda capsids. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;233:682–694. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson NH, Baker TS, Willingman P, Incardona NL. The three-dimensional structure of frozen-hydrated bacteriophage ϕXl74. J. Struct. Biol. 1992;108:168–175. doi: 10.1016/1047-8477(92)90016-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchison CA, III, Sinsheimer RL. The process of infection with bacteriophage ϕX174. X. Mutations in a X lysis gene. Mol. Biol. 1966;18:429–447. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(66)80035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farber MB. Purification and properties of bacteriophage ϕX174 gene D products. J. Virol. 1976;17:1027–1037. doi: 10.1128/jvi.17.3.1027-1037.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng RH, et al. Steven AC. Fungal virus capsids: cytoplasmic compartments for the replication of double-stranded RNA formed as icosahedral shells of asymmetric Gag dimers. Mol. Biol. 1994;244:255–258. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dryden KA, et al. Baker TS. Early steps in reovirus infection are associated with dramatic changes in supramolecular structure and protein conformation: analysis of virions and subviral particles by cryoelectron microscopy and three-dimensional image reconstruction. J. Cell Biol. 1993;122:1023–1041. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.5.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mindich L, Bamford DH. Lipid-containing bacteriophages. In: Calendar R, editor. In The Bacteriophages. Vol. 2. Plenum Press; New York and London: 1988. pp. 475–520. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fane BA, Shien S, Hayashi M. Second-site suppressors of a cold sensitive external scaffolding protein of bacteriophage ϕX174. Genetics. 1993;134:1003–1011. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.4.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newbold JE, Sinsheimer RL. Process of infection with bacteriophage ϕX174. XXXIV. Kinetics of the attachment and eclipse steps of the infection. J. Virol. 1970;5:427–431. doi: 10.1128/jvi.5.4.427-431.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yazaki K. Electron microscopic studies of bacteriophage ϕX174 intact and ‘eclipsing’ particles, and the genome by the staining and shadowing method. J. Virol. Meth. 1981;2:159–167. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(81)90034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanger F, et al. Smith M. Nucleotide sequence of bacteriophage ϕX174 DNA. Nature. 1977;265:687–695. doi: 10.1038/265687a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Incardona NL, Selvidge L. Mechanism of adsorption and eclipse of bacteriophage ϕX174. II. Attachment and eclipse with isolated Escherichia coli cell wall lipopolysaccharide. Virol. 1973;11:775–782. doi: 10.1128/jvi.11.5.775-782.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feige U, Stirm S. On the structure of the Escherichia coli C cell wall lipopolysaccharide core and on its ϕX174 receptor region. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1976;71:566–573. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(76)90824-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jazwinski SM, Lindberg AA, Kornberg A. The lipopolysaccharide receptor for bacteriophages ϕX174 and S13. Virology. 1975;66:268–282. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown DT, MacKenzie JM, Bayer ME. Mode of host cell penetration by bacteriophage ϕX174. J. Virol. 1971;7:836–846. doi: 10.1128/jvi.7.6.836-846.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ilag LL, McKenna R, Yadav MP, BeMiller JN, Incardona NL, Rossmann MG. Calcium ion induced structural changes in bacteriophage ϕX174. J. Mol. Biol. 1994;244:291–300. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerstein M, Lesk AM, Chothia C. Structural mechanisms for domain movements in proteins. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6739–6749. doi: 10.1021/bi00188a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huber R, Bennett WS., Jr. Functional significance of flexibility in proteins. Biopolymers. 1983;22:261–279. doi: 10.1002/bip.360220136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coombs DH, Arisaka F. T4 tail structure and function. In: Karam JD, editor. Molecular Biology of Bacteriophage T4. ASM Press; Washington DC.: 1994. pp. 259–281. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Black LW, Showe MK, Steven AC. Morphogenesis of the T4 head. In: Karam JD, editor. Molecular Biology of Bacteriophage T4. ASM Press; Washington DC.: 1994. pp. 218–258. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rayment I, et al. Holden HH. Three-dimensional structure of myosin- subfragment-1: a molecular model. Science. 1993;261:50–58. doi: 10.1126/science.8316857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cramer WA, et al. Stauffacher CV. Structure-function of channel-forming colicins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomolec. Struct. 1995 doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.24.060195.003143. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bullough PA, Hughson FM, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature. 1994;371:37–43. doi: 10.1038/371037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Incardona NL, Tuech JK, Murti G. Irreversible binding of phage ϕX174 to cell-bound lipopolysaccharide receptors and release of virus-receptor complexes. Biochemistry. 1985;24:6439–6446. doi: 10.1021/bi00344a020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giulian GG, Shanahan MF, Graham JM, Moss RL. Resolution of low molecular weight polypeptides in a non-urea sodium dodecyl sulfate slab polyacrylamide gel system. Feder. Proc. 1985;44:686. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willingmann P, et al. Incardona NL. Preliminary investigation of the phage ϕX174 crystal structure. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;212:345–350. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90129-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker TS, Drak J, Bina M. Reconstruction of the three-dimensional structure of simian virus 40 and visualization of the chromatin core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:422–426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.2.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng RH, Reddy VS, Olson NH, Fisher AJ, Baker TS, Johnson JE. Functional implications of quasi-equivalence in a T=3 icosahedral animal virus established by cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography. Structure. 1994;2:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00029-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adrian M, Dubochet J, Lepault J, McDowall AW. Cryo-electron microscopy of viruses. Nature. 1984;308:32–36. doi: 10.1038/308032a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crowther RA. Procedures for three-dimensional reconstruction of spherical viruses by Fourier synthesis from electron micro-graphs. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. [Biol.] 1971;261:221–230. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1971.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fuller SD. The T=4 envelope of Sindbis virus is organized by interactions with a complementary T=3 capsid. Cell. 1987;48:923–934. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90701-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng RH, et al. Baker TS. Three-dimensional structure of an enveloped alphavirus with T=4 icosahedral symmetry. Cell. 1995;80:621–630. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winkelmann DA, Baker TS, Rayment I. Three-dimensional structure of myosin subfragment-1 from electron microscopy of sectioned crystals. J. Cell Biol. 1991;114:701–713. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.4.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stewart PL, Fuller SD, Burnett RM. Difference imaging of adenovirus: bridging the resolution gap between X-ray crystallography and electron microscopy. EMBOJ. 1993;12:2589–2599. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05919.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]