Abstract

Smooth muscle cells (SMCs) are key components within the vasculature. Dependent on the stimulus, SMC can either be in a proliferative (synthetic) or differentiated state. Alterations of SMC phenotype also appear in several disease settings, further contributing to disease progression. Aims: Here, we asked whether microRNAs (miRNAs, miRs), which are strong posttranscriptional regulators of gene expression, could alter SMC proliferation. Results and Innovation: Employing a robotic-assisted high-throughput screening method using miRNA libraries, we identified hypoxia-regulated miR-24 as a master regulator of SMC proliferation. Proteome profiling showed a strong miR-24-dependent impact on cellular stress-associated factors, overall resulting in reduced stress resistance. In vitro, synthetic miR-24 overexpression had detrimental effects on SMC functional capacity inducing apoptosis, migration defects, enhanced autophagy, and loss of contractile marker genes. Impaired SMC function was mediated in part by the herein identified direct target gene heme oxygenase 1. Ex vivo, miR-24 was shown to inhibit the development of vasculature in a model of engineered heart tissue. Conclusion: Collectively, we report the identification of the hypoxamir-24 as an inhibitor of SMC proliferation, contributing to loss of vascularization. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21, 1167–1176.

Introduction

Endogenous small noncoding microRNAs (miRNAs) are powerful posttranscriptional regulator of various physiological and pathological conditions (17, 21, 22, 24). miRs are capable to control multiple effectors in parallel, thus offering great therapeutic value. The miR biogenesis enzymes Dicer and Drosha were shown to be crucial for the postnatal differentiation and survival of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) suggesting that several miRNAs are indispensible for SMC biology (1, 9). Especially, the miR-143/145 gene cluster was reported to drive SMC differentiation (7). Further studies confirmed the regulatory potential of miR-143/145 to control SMC phenotype (4). Mice lacking miR-143/145 also exhibited a diminished stress response toward vascular injury proofing the general concept of extraordinary miR-143/145 significance for SMC biology (26). Of interest, extracellular communication between endothelial and SMCs also involved the shuttling of miR-143/145 in small vesicles to sustain SMC phenotype in atherosclerosis (16). Phenotype switching is a well-known phenomenon occurring in SMCs describing a stimulus-dependent characteristic switch from a differentiated, contractile to an undifferentiated, more proliferative, synthetic state [early reports in (13, 19)]. Underlying molecular mechanisms include transcription factors such as myocardin fine-balancing the expression level of contractile marker genes (6). In contrast, the platelet-derived growth factor-BB (PDGF-BB) signaling pathway supports the synthetic SMC phenotype by enhancing miR-24 expression (5). Loss of contractile phenotype is also described by downstream effectors (e.g., Trb3 and different SMAD proteins) that contribute to SMC contractile marker gene expression. A successfully employed strategy to identify novel miRNAs with important cellular functions is the transfection of miRNA libraries (8, 22). We thus started our approach by an unbiased miRNA library screen to identify novel miRNAs with important functions in SMC biology. Interestingly, miR-24 is a hypoxia-sensitive miR in the endothelium and contributes to cardiac vascularity after myocardial infarction (10). Next to models of cardiac vascularization in vivo, engineered heart tissue (EHT) is a versatile tool to study vascularization ex vivo (11, 27). Under EHT standard culture conditions, VE-Cadherin:Cre lacZ EHTs develop a primitive and longitudinally orientated vessel-like network on day 18 of culture, where vascular structures can be easily detected by X-Gal staining and light microscopy. As yet, a global functional miR screen to identify the most important miRNAs regulating SMC proliferation has not been performed. We here now by use of a high-throughput robotic-assisted transfection approach applying a miR library report the identification of the hypoxaMiR miR-24 to be of high importance for SMC function and tissue vascularization.

Innovation.

In the present work, we postulate a strong impact of microRNA (miR)-24 on the regulation of smooth muscle cells (SMCs). Enhanced miR-24 expression is deteriorating SMC biology mainly via inducing apoptosis and autophagy, inhibiting proliferation and reducing contractile marker genes. A factor contributing to the observed phenotype is the target gene heme oxygenase 1. Elevated miR-24 expression (e.g., induced by hypoxia) is also impairing vascular density in an engineered heart tissue model. Thus, miR-24 is an interesting candidate to develop novel miRNA-based methods to modulate tissue vascularization.

Results

Pre-miR screening highlights miR impact on human aortic smooth muscle cell viability

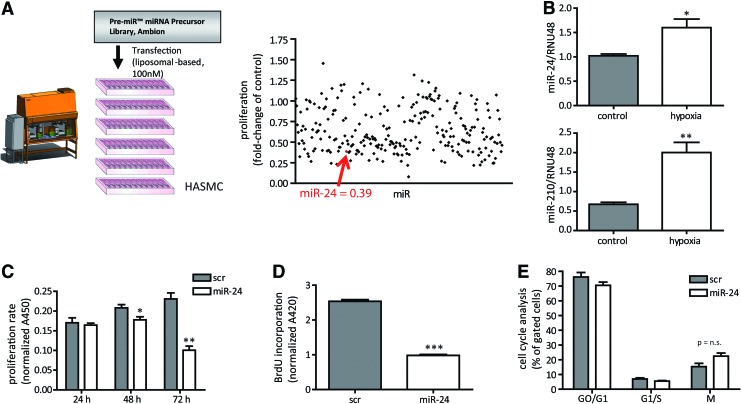

To identify miRNAs that alter human aortic smooth muscle cells (HASMCs), we performed a robotic-assisted high-throughput precursor (pre)-miR screening. Applying a miR library of >250 pre-miRs, liposomal transfection identified several miRs that altered cellular proliferation 72 h after pre-miR transfection (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars). We set a threshold of twofold regulation for further specific analysis and by this identified 100 miRNAs changing cell proliferation (Supplementary Table S2).

FIG. 1.

miR library screening to validate HASMC proliferation. (A) Pre-miRs were transfected to HASMC for 72 h, and WST-1-based proliferation rate was detected. Fold-change of lipofectamine control transfection is plotted. Additionally, robotic-assisted transfection is depicted. N=2 experiments. (B) HASMCs were exposed to hypoxia for 24 h. Afterward, miR expression analysis for miR-24 and miR-210 was performed. N=3 experiments per group. (C) miR-24 was validated as a candidate miR to impact on HASMC proliferation in time course experiments. N=3 experiments per group. (D) BrdU assay was performed to analyze proliferative capacity in miR-24 modulated HASMCs. N=3 experiments per group. (E) Cell cycle analysis in miR-transfected HASMCs. After 72 h of transfection, cells underwent FACS-based cell cycle analysis. N=3 experiments per group. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; HASMCs, human aortic smooth muscle cells; miR, miRNA, microRNA; n.s., not significant. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

miR-24 impairs HASMC viability

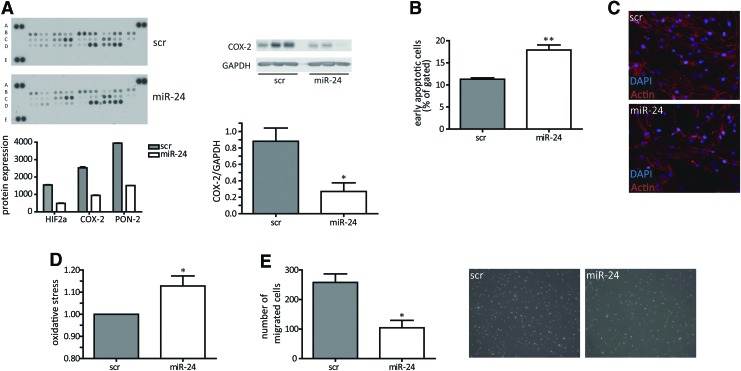

Among theses candidate miRs, miR-24 was chosen for further analysis because of its strong effects on HASMC proliferation and its well-known role being a “hypoxaMir” in vascular cells (10). Indeed, hypoxia significantly increased miR-24 levels in HASMCs (Fig. 1B), a finding that previously has been also reported in endothelial cells (10). Validation experiments confirmed the initial screening results for miR-24 to function as a potent antiproliferative miRNA in time-dependent manner with most prominent effects at 72 h after initial transfection with high efficacy (Fig. 1C; Supplementary Fig. S1). Of interest, the other miR-24 gene cluster members miR-23/27 also impaired proliferative potential of HASMCs (Supplementary Table S1). Next to the proliferation assay based on turnover of WST-1, we additionally checked BrdU incorporation rate, which was also reduced upon miR-24 overexpression (Fig. 1D). We next tested whether miR-24-induced inhibition of HASMC proliferation was mediated through changes in the cell cycle. Surprisingly, cell cycle progression was not changed upon miR-24 transfection to HASMCs (Fig. 1E; Supplementary Fig. S2). Thus, alterations in cell cycle are not likely to be responsible for the observed phenotype. Next, we employed a proteomic-based approach to study the effects of miR-24 on stress response proteins. This approach revealed the repression of several factors important to resist cellular stress, such as hypoxia-inducible factor 2α, cyclooxygenase (COX-2), and paraoxonase-2 (Fig. 2A; Supplementary Table S3), suggesting miR-24 overexpression resulted in decreased resistance to stress. Validation experiments confirmed that miR-24 induced repression of COX-2 (Fig. 2A). In agreement, miR-24 overexpression led to a significant increase in apoptosis levels in HASMCs (Fig. 2B) and to disturbed actin filament appearance (Fig. 2C) suggesting increased cellular stress.

FIG. 2.

miR-24 impairs the HASMC activity. Control (scr) or miR-24 was transfected liposomally to HASMC for 72 h, and subsequent analysis was applied. (A) Proteome profile of 26 stress-related factors was analyzed in scrambled (scr) or miR-24-transfected HASMC. Most deregulated ones are shown. Lysates for proteome profiling were a mixture of three biological replicates each. Validation western blotting was performed for COX-2 as seen on the right. N=3 experiments per group. (B) Apoptosis rate was measured as Annexin-V-positive and propidium iodide-negative cells. (C) Actin filament organization is impaired by miR-24. Cells were stained for actin filaments using phalloidin. (D) Intracellular oxidative stress was FACS-measured applying Invitrogen ROX assay. N=6 experiments per group. (E) Boyden-chamber migration was determined for 4–8 h in a gradient toward chemoattractant. N=3 experiments per group. *p<0.05; **p<0.01. COX, cyclooxygenase; mFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

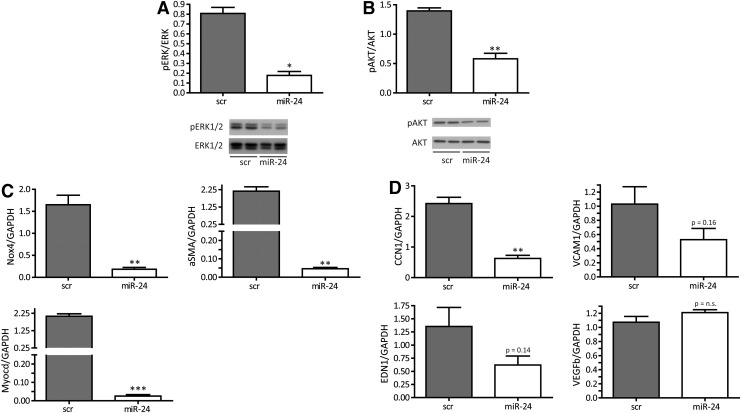

Enhanced miR-24 expression reduces functional capacity of HASMCs

To understand the underlying molecular events leading to miR-24-induced decrease in stress resistance, a number of further studies were performed. To study additional reasons of increased apoptosis and further functional consequences, we employed an assay to study miR-24 effects on the generation of intracellular oxidative stress. Indeed, miR-24 overexpression increased oxidative stress and impaired migratory capacity in a Boyden-chamber assay (Fig. 2D, E). In line, important survival pathways such as extracellular kinase (ERK)-mediated signaling and the Akt pathway were significantly inhibited when miR-24 was overexpressed in HASMCs (Fig. 3A, B). In addition, there was a loss of expression of contractile marker genes such as NOX-4, αSMA, and MYOCD (Fig. 3C) upon miR-24 overexpression being in line with the observed deregulated phenotypic appearance of HASMCs (Fig. 2C). Time-dependent expression patterns of those genes reflected an early response to miR-24 overexpression (data not shown). In addition to contractile marker genes, we validated gene expression of angiogenic genes cysteine-rich angiogenic inducer 61 (CCN1), endothelin 1 (EDN1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1), and vascular endothelial growth factor B (VEGFb) (Fig. 3D). Of those, the expression level of proangiogenic CCN1 was most strongly repressed upon enhanced miR-24 expression.

FIG. 3.

miR-24 interferes with prosurvival and differentiation pathways. (A) Western blot data for pERK1/2 and ERK1/2 in scr- and miR-24-transfected HASMC. N=3 experiments per group. (B) Western blot data for pAKT and AKT in scr- and miR-24-transfected HASMCs. N=3 experiments per group. (C) RT-PCR analysis of contractile marker genes NOX4, ACTA2, and MYOCD in HASMCs after 72 h of transfection with scr or miR-24. N=3 experiments per group. (D) Angiogenic gene expression for CCN1, VCAM1, EDN1, and VEGFb was monitored after 72 h in miR-24-transfected HASMCs. N=3 experiments per group. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. EDN1, endothelin 1; ERK, extracellular kinase; RT-PCR, real-time polymerase chain reaction; VCAM1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; VEGFb, vascular endothelial growth factor B.

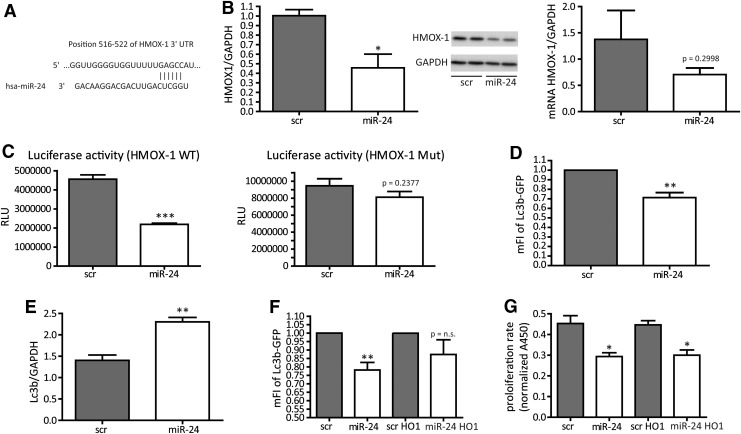

HMOX-1 is a direct target for miR-24

We next wanted to identify a direct miR-24 target that helps to understand the miR-24-induced phenotype of HASMCs, for example, increase of cellular apoptosis and loss of proliferation and contractile marker genes. We thus screened putative miR-24/target gene interactions via the software and miRNA database targetscan (targetscan.org) and identified heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1, HO-1) to be an interesting candidate as it is an important and well-established cytoprotective factor (25). An indirect search investigating the 3′-UTR region of HO-1 revealed potential miR-24 base pairing (Fig. 4A). We conducted several experiments to validate this single miR-24 binding site to be of relevance in miR-24/HMOX-1 interaction. Indeed, increased miR-24 levels effectively repressed HMOX-1 expression at the protein level and (as a trend) at the mRNA level (Fig. 4B), suggesting translational repression to be the main mechanism of miR-24 in HMOX-1 regulation in human SMCs. In murine cells, miR-24-dependent repression of HMOX-1 was also observed confirming a conserved mechanism (Supplementary Fig. S3). To next validate direct miR-24 binding to HMOX-1 3′-UTR region, luciferase reporter gene constructs were generated. Co-transfection of wild-type reporter construct along with normalizing plasmid and miR-24 precursors significantly lowered luciferase activity indicating miR-24-mediated repression of HMOX-1 (Fig. 4C). When the miR-24 binding site was mutated, however, the repressive effects of miR-24 were abolished further indicating direct miR-24 targeting to the HMOX-1 3′-UTR region (Fig. 4C). As the HMOX-1 enzyme system was suggested to have a role in the regulation of autophagy (3), we next tested the effects of miR-24 on HASMC autophagy. Indeed miR-24 increased basal autophagy (Fig. 4D). The specific inhibition of autophagy by wortmannin, however, had no rescuing effects on the antiproliferative phenotype of miR-24 overexpression (data not shown), suggesting autophagy and apoptosis to have independent effects in the context of miR-24-mediated functions in HASMC. Lc3b, a common marker gene for autophagy induction, is also upregulated upon miR-24 transfection (Fig. 4E). We next tested if the miR-24-mediated effects on HASMC biology were at least in part dependent of HMOX1. For this, we employed viral-based miR-24-resistant HMOX1 overexpression (HMOX1 lacking the miR-24 binding site in 3′-UTR), which indeed partly normalized the increased miR-24-induced autophagy (Fig. 4F). This reflects an important role of the miR-24 target HMOX1 to balance HASMC autophagy. Other miR-24 dependent effects on proliferation rate or oxidative stress were not affected by HMOX-1 overexpression (Fig. 4G and data not shown).

FIG. 4.

HMOX-1 is a direct miR-24 target gene. (A) Identification of putative miR-24 binding site via targetscan.org in HMOX-1 3′-UTR. (B) HMOX-1 expression (western blot and RT-PCR) after 72 h of scr or miR-24 transfection. N=3 experiments per group. (C) Luciferase reporter gene assays to confirm miR-24 binding to HMOX-1 3′-UTR. WT or mutated (Mut) 3′-UTR were validated in a luciferase-based reporter assay. RLU normalized to beta-Gal Plasmid. N=3 experiments per group (WT), n=6 experiments per group (Mut). (D) Basal autophagy validated by FACS Lc3b-GFP staining in scr- or miR-24-transfected HASMCs. N=4 experiments per group. (E) RT-PCR analysis for Lc3b after miR-24 modulation. N=3 experiments per group. (F) Autophagy detection in scr- or miR-24-transfected HASMC, with or without the supplementation for HMOX-1 supplied in a 3′-UTR-deficient adenovirus. N=5 experiments per group. (G) Proliferation capacity in miR-transfected (plus/minus HMOX-1 virus rescue) HASMCs. Cells were transfected with scr miR or miR-24 without or in the presence of HMOX-1 virus. Proliferation behaviour was analyzed by applying WST-1 reagent. N=3 experiments per group. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001. HMOX-1, HO1, heme oxygenase 1; WT, wild-type.

Translation of the in vitro findings into a model of vascularized ex vivo myocardium

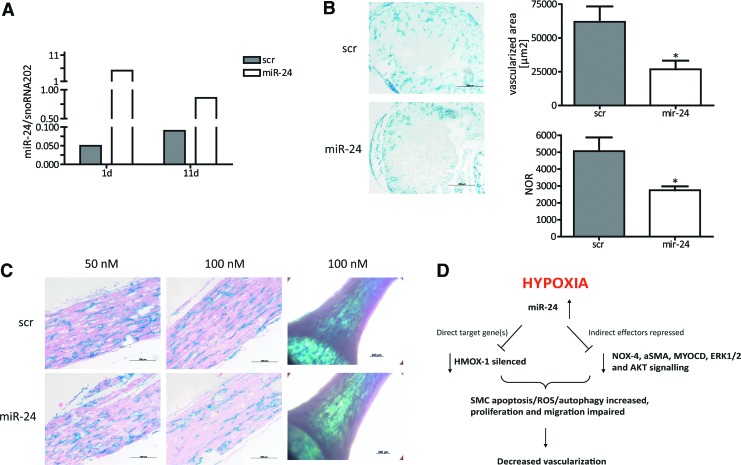

To translate our in vitro findings into an in vivo scenario, we employed the following approach. EHTs represent an excellent opportunity to study the effects of novel substances in a well-organized three-dimensional construct of ex vivo generated vascularized myocardium (15). Our hypothesis was that the detrimental effects of miR-24 on vascular SMCs would affect overall vascularization in such EHTs. For this purpose, we generated EHTs with genetically labelled endothelial cells for the simple and robust identification of vascular structures ex vivo. Heterozygous inducible Cre-positive VE-Cadherin-Cre-ERT2 mice (2, 18) were crossed with homozygous Rosa26R-LacZ reporter mice to specifically label endothelial cells by LacZ gene expression as detailed in the “Materials and Methods” section. To confirm transfection efficiency in EHTs, miR-24 expression levels in miR-24-transfected EHTs were analyzed in comparison to control-transfected EHTs. miR-24 expression level were highest 1 day after transfection (fivefold of the miR-24 mRNA levels in scr EHTs) and decreased to day 4 (twofold) and day 11 (onefold), indicating that a transient effect of miR-24 that was most pronounced in the first days of EHT culture (Fig. 5A). miR-24- or control-transfected VE-CadherinxRosa26R-LacZ EHTs were treated with 5-OH-tamoxifen to induce LacZ expression in endothelial cells, stained with X-gal, fixed, paraffin-embedded, and cross sectioned. Sections were quantified without counterstaining to avoid potential color overlay of the LacZ signal. Native VE-Cadherin EHT showed endothelial cell-specific X-gal+ tubular structures with clearly discernible lumina, primarily located in the border zones of the EHT (Fig. 5B). Less X-gal-positive regions and tube-like structures were detected in miR-24-transfected VE-Cadherin EHTs (46%), and endothelial cell density was 57% lower in miR-24-treated EHTs (100 nM; Fig. 5B). These findings in cross sections were supported by longitudinal histological sections, which showed extensive interconnected endothelial cells forming branched vascular networks in EHTs (Fig. 5C). Again, vascular structure appeared less dense in miR-24-treated EHTs in the whole mount view (Fig. 5C). In addition, EHT showed a loss of smooth muscle actin (ACTA2) expression under miR-24 overexpression conditions (Supplementary Fig. S4). These new data suggest that miR-24 overexpression not only in vitro but also in an ex vivo EHT model impairs vascularization. Whether these effects are mediated via the previously identified detrimental effects of miR-24 on endothelial cells (10) and/or the detrimental effects on SMCs as shown in this report remains to be determined in future studies.

FIG. 5.

miR-24 deteriorates EHT vascularization. (A) Synthetic overexpression of miR-24 in murine EHT. After 1 and 11 days, miR-24 expression was monitored. (B) Native paraffin cross sections after X-gal staining of scr- and miR-24-transfected EHTs, both in a concentration of 100 nM, served for endothelial cell quantification. Identified X-gal-positive area and detected number of X-gal-positive regions (NOR) were measured in native cross sections with Axiovision Zeiss software. N=6 (scr) and n=5 (miR-24) EHTs. Scale bar indicates 200 μm. (C) Eosin-stained longitudinal EHT paraffin sections of scr- and miR-24-transfected EHTs (50 and 100 nM transfection, respectively) as wells as light microscopic images of whole mount EHTs transfected with 100 nM miR concentration. Scale bar indicates 200 μm. (D) Summary for miR-24 function in HASMC. Enhanced miR-24 expression alters phenotypic appearance and impacts on decisive cellular functions regulating vascular appearance. *p<0.05. EHT, engineered heart tissue.

Discussion

Vascular injury (e.g., seen in atherosclerosis or in-stent restenosis) involves the activation of resident, quiescent SMC to a more proliferative status. Thus, a broader knowledge about the involvement of miRNAs in the proliferation of SMCs is highly valuable. In this study, we could identify miR-24 as a strong antiproliferative miR by a robotic-assisted miR screening approach (mechanistic scheme summarized in Fig. 5D). In line with previous results, miR-24 is designated as a “hypoxaMir.” Hypoxia itself is a strong inductor of proliferation in SMC (12). Enhanced miR-24 expression triggers functional SMC defects as well as the loss of contractile potential measured by strong repression of marker genes, which is in agreement to the study from Chan et al. (5). In contrast, we did not observe a parallel induction of a clear synthetic phenotype characterized by elevated proliferation. It is more likely that miR-24 transfection put cells into a more intermediate cellular status with less proliferation and contractile activity. Of note, miR-24 is a clustered miR altogether with miR-23/27 (5). In our screening, we also observed detrimental effects on proliferation rate of the other cluster members, whereas miR-24 effects were strongest. At the transcriptional level, regulatory mechanisms for this miR cluster are less studied and may also be of interest for extensive future analysis. Impairment in proliferation, however, cannot be explained by cell cycle alterations as we did not see any defects in cell cycle progression triggered by miR-24. Of note, endogenous miR-24 repression did not influence the HASMC activity demonstrating the crucial role of balanced miR-24 expression (data not shown). miR-24 is altering the expression level of various cellular stress proteins and induces apoptosis and oxidative stress under basal conditions. Prominent cellular survival pathways (e.g., AKT and ERK) are also effectively repressed via miR-24. This likely contributes to the loss of the migratory potential of SMCs. There are some different previous results about miR-24 in SMC present in the literature. Whereas Chan et al. (5) identified PDGF-BB driving in a miR-24-dependent manner a more synthetic phenotype in SMC, miR-24 has also recently been reported to inhibit SMC migration capacity during vascular injury (20), being in line with our observations. The miR-24-dependent effect on CCN1 expression may also reflect a paracrine function since this factor was reported to be activated in neovascularization processes (14). The identification of cytoprotective HMOX-1 as a direct miR-24 target gene implies high relevance of miR-24-dependent pathways in SMC. Indeed, HMOX-1 could recently be linked to counteract apoptosis and autophagy in renal cells (3). Here, miR-24-dependent repression of SMC HMOX-1 also induces apoptosis and autophagy. In our study, HMOX-1 supplementation could partly rescue the defective autophagy phenotype additionally supporting the impact of miR-24/HMOX-1 axis in SMC. Further functional impairment of SMC function (e.g., proliferation, oxidative stress), however, could not be reverted by HMOX-1 suggesting that other known or unknown miR-24 target genes participate in these processes, for example, p21 protein-activated kinase 4 (PAK4) and c-myc (Supplementary Fig. S5). The identification of further miR-24 downstream effectors is thus an open issue and remains to be determined in future studies. Translation of in vitro findings to an ex vivo model of EHT validated miR-24 effects on vascular cells. Efficient miR-24 modulation was seen in the developing EHT, which finally disturbed the appearance of vascular structures. We think that this is a further evidence for proapoptotic properties of miR-24 in the interplay between endothelial and SMCs. Thus, during vascular injury, for example, miR-24 should be held at a low expression level. Therapeutic intervention may be of use applying antagonistic chemistries (e.g., antagomir or locked nucleic acid chemistry). The efficacy of therapeutic miR-24 targeting should thus be tested in other models of vasculature.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

HASMCs were purchased from Invitrogen (Gibco) and cultured in SmGM-2 (Lonza) supplemented with human epidermal growth factor, insulin, human fibroblast growth factor-B, gentamicin/amphotericin-B, and 10% fetal bovine serum under standard cell culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2). In paraformaldehyde (PFA)-fixed cells, actin cytoskeleton was stained applying TRITC-tagged Phalloidin (Sigma; #1951). Hypoxia was considered as an oxygen level of 0.1–0.2% and was performed for 24 h. SV40-transformed endothelial cells were purchased from ATTC (#CRL-2167) and cultivated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Transfection

Cells were transfected at a confluency of 60–70% 1 day after seeding. Specific miRNA (pre-miR-24; Ambion, Ambion human pre-miR Library #4385830) or control miRNA (pre-miR Negative Control #2; Ambion) at a final concentration of 100 nM and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) were incubated separately with Opti-MEM I (Invitrogen) for 5 min, then mixed and incubated for 20 min. Cell medium was replaced for the transfection reaction. After 4 h, the medium was refreshed. Cells were collected and analyzed after 72 h.

Pre-miRNA screening and proliferation assay

HASMCs were seeded in 96-well cell culture plates and transfected with Human Pre-miR Library (Ambion) at a final concentration of 100 nM 1 day after seeding manually or using a robot pipetting device (Bravo System; Agilent). To measure the proliferative capacity in miRNA-modulated cells, a WST-1 proliferation assay (Roche) was applied. Seventy-two hours after transfection, the medium was changed and replaced by WST-1 reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. Finally, WST-1 absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Migration assay

For Boyden-chamber migration, cells were incubated for 1 h with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, pelleted, and resuspended in SmGM-2 with 0.1% bovine serum albumin. Twenty-five thousand cells per sample were seeded on fibronectin coated trans-well inserts (BD Biosciences), previously placed in wells containing chemoattractants (50 pg/μl VEGF, 100 pg/μl stromal cell-derived factor). Images were captured after 6 and 24 h, and the number of migrated cells was counted using NIS-elements BR software (Nikon).

Autophagy measurement

HASMCs were seeded in 48-well cell culture plates and transfected with miRNA 1 day after splitting. Immediately after transfection, LC3b-GFP construct was added. After 4 h, the medium was refreshed and cells were incubated for another 48 h. Finally, cells were harvested, fixated with 0.5% PFA, and analyzed for GFP fluorescence on Guava FACS Easycyte. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) data were analyzed using FlowJo software.

Real-time polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA isolation was performed with TriFast reagent (Peqlab) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For gene expression analysis, RNA was reverse transcribed with iScript Select cDNA Synthesis Kit (Biorad) and Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis was performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Biorad). Primer sequences were as following: NOX4: forward 5′-CCGGCTGCATCAGTCTTAACC-3′, reverse 5′-TCGGCACAGTACAGGCACAA-3′; Acta2: forward 5′-CCTGACTGAGCGTGGCTATT-3′, reverse 5′-GATGAAGGATGGCTGGAACA-3′; Myocd: forward 5′-CTGTTCCTGCAGCTCCAAAT-3′, reverse 5′-GGAGACAAGGGGGTATTGCT-3′; Lc3b: forward 5′-AACAAAGAGTAGAAGATGTCCGAC-3′, reverse 5′-GAACTTTGTTTTATCCAGAACAGG-3′; c-myc: forward 5′-TCAAGAGGCGAACACACAAC-3′, reverse 5′-GGCCTTTTCATTGTTTTCCA-3′; GAPDH: forward 5′-CCAGGCGCCCAATACG-3′, reverse 5′-CCACATCGCTCAGACACCAT-3′. Primers for human CCN1 (CYR61), VCAM1, EDN1, CDK1/2/4/6, PAK4, and VEGFb were purchased from Qiagen as Quantitect primer sets. To analyze miRNA expression, two-step real time-PCR primer sets from Applied Biosystems were used according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNU48 and sno-RNA-202 served as a housekeeping control.

Western blotting

About 10–40 μg of total protein were separated by sodium dodeyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and analyzed by western blotting using standard protocols. Antibodies were purchased from: HMOX-1 (R&D Systems; AF3776), ERK (Cell Signaling; #9101/02), AKT (Cell Signaling; #9272/75), COX-2 (Santa Cruz; #1747), ACTA2 (ab5694), and GAPDH (Abcam; ab8245). Luminol reagent was used to visualize the signals on the membrane using X-ray film. The band intensity was calculated by applying ImageJ software.

Proteome profiler

Human Cell Stress Array (R&D Systems; ARY018) was performed with 300 μg of cell lysate pooled from three independent experiments following the instructions of the manufacturer. ImageJ software was applied to calculate signal intensities.

miR target prediction and luciferase reporter gene assay

The miRNA database and target prediction tool TargetScan (http://target-scan.org) was screened to identify potential miRNA targets. A luciferase reporter assay system was applied to validate potential miRNA targets. Human HMOX-1 3′-UTR (fragment of ∼500 bp) containing a miRNA binding site for miR-24 was PCR amplified and cloned into SpeI and HindIII restriction sites of pMIR-REPORT vector (Ambion). The resulting construct was co-transfected with miRNAs of interest and beta-galactosidase control plasmid (Promega) into HEK293 reporter cells in 48 wells by use of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). About 0.02 μg plasmid DNA and 100 nM miRNA were applied. Cells were incubated for 24 h before measuring luciferase and β-galactosidase activity with appropriate substrates (Promega). Mutation of the wild-type HMOX-1 3′-UTR plasmid was performed applying site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent).

Apoptosis assay

Transfected cells were harvested after 72 h and stained with the Annexin-V-Fluos kit from Roche Diagnostics according to the manufacturers' instructions. FACS analysis was performed on a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences).

BrdU enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

To measure the proliferative capacity in miR-24-modulated HASMC, a colorimetric BrdU enzyme linked immunosorbent assay kit from Roche (#11647229001) was applied. Standard procedures were performed according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Cell cycle analysis

Analysis of miR-transfected cells was performed applying Guava Cell Cyle Reagent (Millipore) according to the manufacturers' instructions. Subsequent FACS analysis was performed on guava easyCyte (Millipore).

Detection of oxidative stress

To monitor intracellular oxidative stress, cells were stained in culture with CellROX Green Reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Afterward, FACS analysis was performed on guava easyCyte (Millipore).

Mouse model for genetic labeling of endothelial cells

Heterozygous VE-Cadherin-Cre-ERT2 mice [kindly provided by Prof. Florian Limbourg; (2, 18)] were crossed with homozygous Rosa26R-LacZ reporter mice to specifically label endothelial cells by LacZ gene expression. Double transgenic mice were identified by genotyping via PCR from tail DNA using primers R1295: 5′-GCG AAG AGT TTG TCC TCA ACC-3′, R523: 5′-GGA GCG GGA GAA ATG GAT ATG -3′, R26F2: 5′-AAA GTC GCT CTG AGT TGT TAT-3′, CRE1: 5′-GCC TGC ATT ACC GGT CGA TGC AAC GA-3′, and CRE2: 5′-GTG GCA GAT GGC GCG GCA ACA CCA TT-3′. In Rosa26R-LacZ reporter mice, a floxed stop codon is inserted between the promoter sequence and the LacZ gene, inactivating the LacZ gene until Cre recombinase expression is induced. Cre-mediated recombination leads to the excision of the floxed stop codon and LacZ gene expression. During EHT culture, Cre expression was induced by the addition of o-hydroxytamoxifen (1 nM) to the culture medium on day 15 for 48 h. The endothelial cell specificity of the system is obtained by control of the inducible Cre-ERT2 fusion protein by the endothelial cell-specific surface protein VE-Cadherin and was verified in mice (data not shown).

Neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes

Neonatal mice (day 0–1, postnatal) were sacrificed by decapitation. After heart extraction, neonatal heart cells were isolated by a serial DNase/trypsin digestion based on methods to isolate neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (23). The resulting cell population was immediately subjected to EHT generation. Experimental procedures were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee, University of Hamburg.

Sylgard posts and Teflon spacers

Sylgard 184 (Dow Corning) was used to fabricate silicone racks with silicone posts for EHT cultivation, and Teflon spacers for casting mold generation were manufactured as previously described (15). Silicone racks were produced by Silitec GmbH & Co. KG.

Generation and culture of EHT

To generate EHTs, a reconstitution mix was prepared on ice as follows (final concentration): unpurified 6.8×106 cells/ml, 5 mg/ml bovine fibrinogen (stock solution: 200 mg/ml fibrinogen plus aprotinin 100 μg/ml in NaCl 0.9%; Sigma F4753), 10% Matrigel (BD Bioscience; 356235). 2×Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) was added to match the volumes of fibrinogen and thrombin stock (100 U/ml; Sigma T7513) to ensure isotonic conditions. Casting molds were prepared as previously described (15). For each EHT, 97 μl reconstitution mix was briefly mixed with 3 μl thrombin and pipetted into the agarose slot. For fibrinogen polymerization, the constructs were placed in a 37°C, 7% CO2 humidified cell culture incubator for 2 h. The racks were transferred to 24-well plates filled with the culture medium. EHTs were kept in a 37°C, 7% CO2 humidified cell culture incubator. The cell culture medium was changed after 48 h and consisted of DMEM (Biochrom F0415), 10% horse serum (Gibco 26050), 2% chick embryo extract, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco 15140), insulin (10 μg/ml; Sigma I9278), and aprotinin (33 μg/ml; Sigma A1153).

Transfection of murine EHT

Transfection of VE-CadherinxRosaR-26 EHTs was performed with Lipofectamine™ 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The amount of miRNA and transfection agent was adapted to the use for the EHT culture format. After casting, EHTs were immediately placed into the wells including the transfection mix. EHTs were kept in the transfection mix at 37°C and 7% CO2 for 24 h. Subsequently, EHTs were transferred to a fresh plate containing the EHT culture medium.

Histology

For X-gal staining, EHTs (whole-mount) were transferred to a clean dish containing phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, w/o MgCl2, w/o CaCl2; Gibco). The tissue was washed two times with PBS for 10 min. Then, the samples were transferred to a dish containing the prefixation solution (20×PBS [64 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM KH2PO4, 26 mM KCl, 2.7 M NaCl, pH 7.4], 5% [v/v]; 37% formaldehyde, 5% [v/v]; 25% glutaraldehyde, 0.2% [v/v] in aqua ad injectabilia) for 45 s. The prefixation solution was discarded immediately in two times PBS washing steps for 10–20 min. Staining was performed in the solution (20×PBS [64 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM KH2PO4, 26 mM KCl, 2.7 M NaCl, pH 7.4], 5% [v/v]; potassium ferricyanide crystalline [500 mM], 1% [v/v]; potassium ferricyanide trihydrate [500 mM], 1% [v/v]; magnesium chloride [1 M], 0.2% [v/v] in aqua ad injectabilia) containing 0.4 mg/ml X-gal (Sigma B4252) at 37°C over night. The X-gal-positive cells could be detected by the blue staining. After staining, samples were washed in PBS for 2–3 min and postfixed with Histofix® (Roth) for 60 min. Paraffin embedding, sectioning (4 μm), and eosin staining was performed according to standard procedures. Photographic images of the slides were taken with a microscope (Zeiss-Axioplan IM-35), and the suitable software (Zeiss-Axiocam) was used to quantify blue regions in the sections.

RNA isolation from EHT

Total RNA was extracted from 1 EHT using TRIzol® (Invitrogen) reagent (300 μl per EHT) according to the manufacturers' instructions. EHTs were homogenized by the use of a TissueLyser® (Qiagen) at a vibration frequency of 30 Hz. RNA concentration was determinded by measuring the absorbance at a wavelength of 260 nm with a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop® ND-1000; PeqLab). Absorbance was also determined at the wavelength of 280 nm, and the ratio A260/A280 was calculated to test for purity. RNA samples were stored at −80°C for further use.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, GrapPad Prism (Version 4) was applied. In case of two groups, unpaired t-test was performed, unless Figure 2D where paired t-test was performed. Error bars in graphs indicate standard error of the mean. Asterisk mean: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- EDN1

endothelin 1

- EHT

engineered heart tissue

- ERK

extracellular kinase

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- HASMC

human aortic smooth muscle cell

- HMOX-1, HO1

heme oxygenase 1

- mFI

mean fluorescence intensity

- miR, miRNA

microRNA

- PAK4

protein-activated kinase 4

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PDGF-BB

platelet-derived growth factor-BB

- RLU

relative luciferase unit

- RT-PCR

real-time polymerase chain reaction

- SMC

smooth muscle cell

- VCAM1

vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

- VEGFb

vascular endothelial growth factor B

- WT

wild-type

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mortimer Korf-Klingebiel and Prof. Kai Wollert for providing HMOX-1 virus and Prof. Lucie Carrier for providing Lc3b-GFP virus. Histological standard procedures were performed by the HEXT core facility (UKE, Hamburg) mouse pathology (http://uke.de/medizinische-fakultaet/core-facilities/index_ENG_75082.php).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors disclose support from the IFB-Tx (BMBF 01EO0802; T.T.) and DFG TH 903/10-1 (T.T.). T.T. and J.F. have filed patents in the field of cardiovascular miRNA diagnostics and therapeutics. The work of A.S. and T.E. was supported by the EU FP7 Angioscaff and BIODESIGN projects and the German Ministry of Research and Education, BMBF (DZHK, German Centre for Cardiovascular Research).

References

- 1.Albinsson S, Skoura A, Yu J, DiLorenzo A, Fernandez-Hernando C, Offermanns S, Miano JM, and Sessa WC. Smooth muscle miRNAs are critical for post-natal regulation of blood pressure and vascular function. PLoS One 6: e18869, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alva JA, Zovein AC, Monvoisin A, Murphy T, Salazar A, Harvey NL, Carmeliet P, and Iruela-Arispe ML. VE-Cadherin-Cre-recombinase transgenic mouse: a tool for lineage analysis and gene deletion in endothelial cells. Dev Dyn 235: 759–767, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee P, Basu A, Wegiel B, Otterbein LE, Mizumura K, Gasser M, Waaga-Gasser AM, Choi AM, and Pal S. Heme oxygenase-1 promotes survival of renal cancer cells through modulation of apoptosis- and autophagy-regulating molecules. J Biol Chem 287: 32113–32123, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boettger T, Beetz N, Kostin S, Schneider J, Kruger M, Hein L, and Braun T. Acquisition of the contractile phenotype by murine arterial smooth muscle cells depends on the Mir143/145 gene cluster. J Clin Invest 119: 2634–2647, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan MC, Hilyard AC, Wu C, Davis BN, Hill NS, Lal A, Lieberman J, Lagna G, and Hata A. Molecular basis for antagonism between PDGF and the TGFbeta family of signalling pathways by control of miR-24 expression. EMBO J 29: 559–573, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Kitchen CM, Streb JW, and Miano JM. Myocardin: a component of a molecular switch for smooth muscle differentiation. J Mol Cell Cardiol 34: 1345–1356, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cordes KR, Sheehy NT, White MP, Berry EC, Morton SU, Muth AN, Lee TH, Miano JM, Ivey KN, and Srivastava D. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature 460: 705–710, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eulalio A, Mano M, Dal Ferro M, Zentilin L, Sinagra G, Zacchigna S, and Giacca M. Functional screening identifies miRNAs inducing cardiac regeneration. Nature 492: 376–381, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan P, Chen Z, Tian P, Liu W, Jiao Y, Xue Y, Bhattacharya A, Wu J, Lu M, Guo Y, Cui Y, Gu W, Gu W, and Yue J. miRNA biogenesis enzyme Drosha is required for vascular smooth muscle cell survival. PLoS One 8: e60888, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiedler J, Jazbutyte V, Kirchmaier BC, Gupta SK, Lorenzen J, Hartmann D, Galuppo P, Kneitz S, Pena JT, Sohn-Lee C, Loyer X, Soutschek J, Brand T, Tuschl T, Heineke J, Martin U, Schulte-Merker S, Ertl G, Engelhardt S, Bauersachs J, and Thum T. MicroRNA-24 regulates vascularity after myocardial infarction. Circulation 124: 720–730, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fink C, Ergun S, Kralisch D, Remmers U, Weil J, and Eschenhagen T. Chronic stretch of engineered heart tissue induces hypertrophy and functional improvement. FASEB J 14: 669–679, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frid MG, Aldashev AA, Dempsey EC, and Stenmark KR. Smooth muscle cells isolated from discrete compartments of the mature vascular media exhibit unique phenotypes and distinct growth capabilities. Circ Res 81: 940–952, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groschel-Stewart U, Chamley JH, Campbell GR, and Burnstock G. Changes in myosin distribution in dedifferentiating and redifferentiating smooth muscle cells in tissue culture. Cell Tissue Res 165: 13–22, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanna M, Liu H, Amir J, Sun Y, Morris SW, Siddiqui MA, Lau LF, and Chaqour B. Mechanical regulation of the proangiogenic factor CCN1/CYR61 gene requires the combined activities of MRTF-A and CREB-binding protein histone acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem 284: 23125–23136, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen A, Eder A, Bonstrup M, Flato M, Mewe M, Schaaf S, Aksehirlioglu B, Schwoerer AP, Uebeler J, and Eschenhagen T. Development of a drug screening platform based on engineered heart tissue. Circ Res 107: 35–44, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hergenreider E, Heydt S, Treguer K, Boettger T, Horrevoets AJ, Zeiher AM, Scheffer MP, Frangakis AS, Yin X, Mayr M, Braun T, Urbich C, Boon RA, and Dimmeler S. Atheroprotective communication between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells through miRNAs. Nat Cell Biol 14: 249–256, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, and Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 75: 843–854, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monvoisin A, Alva JA, Hofmann JJ, Zovein AC, Lane TF, and Iruela-Arispe ML. VE-cadherin-CreERT2 transgenic mouse: a model for inducible recombination in the endothelium. Dev Dyn 235: 3413–3422, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosse PR, Campbell GR, Wang ZL, and Campbell JH. Smooth muscle phenotypic expression in human carotid arteries. I. Comparison of cells from diffuse intimal thickenings adjacent to atheromatous plaques with those of the media. Lab Invest 53: 556–562, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talasila A, Yu H, Ackers-Johnson M, Bot M, van Berkel T, Bennett M, Bot I, and Sinha S. Myocardin regulates vascular response to injury through miR-24/-29a and platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: 2355–2365, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thum T, Gross C, Fiedler J, Fischer T, Kissler S, Bussen M, Galuppo P, Just S, Rottbauer W, Frantz S, Castoldi M, Soutschek J, Koteliansky V, Rosenwald A, Basson MA, Licht JD, Pena JT, Rouhanifard SH, Muckenthaler MU, Tuschl T, Martin GR, Bauersachs J, and Engelhardt S. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature 456: 980–984, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ucar A, Gupta SK, Fiedler J, Erikci E, Kardasinski M, Batkai S, Dangwal S, Kumarswamy R, Bang C, Holzmann A, Remke J, Caprio M, Jentzsch C, Engelhardt S, Geisendorf S, Glas C, Hofmann TG, Nessling M, Richter K, Schiffer M, Carrier L, Napp LC, Bauersachs J, Chowdhury K, and Thum T. The miRNA-212/132 family regulates both cardiac hypertrophy and cardiomyocyte autophagy. Nat Commun 3: 1078, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webster KA, Discher DJ, and Bishopric NH. Induction and nuclear accumulation of fos and jun proto-oncogenes in hypoxic cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 268: 16852–16858, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wightman B, Ha I, and Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell 75: 855–862, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu ML, Ho YC, and Yet SF. A central role of heme oxygenase-1 in cardiovascular protection. Antioxid Redox Signal 15: 1835–1846, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xin M, Small EM, Sutherland LB, Qi X, McAnally J, Plato CF, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, and Olson EN. MicroRNAs miR-143 and miR-145 modulate cytoskeletal dynamics and responsiveness of smooth muscle cells to injury. Genes Dev 23: 2166–2178, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmermann WH, Fink C, Kralisch D, Remmers U, Weil J, and Eschenhagen T. Three-dimensional engineered heart tissue from neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Biotechnol Bioeng 68: 106–114, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.