Significance

Saffron is a triploid, sterile species whose red stigmas constitute the most expensive spice on Earth. The color, the taste, and the aroma of the spice are owed to the crocus-specific apocarotenoid accumulation of crocetin/crocins, picrocrocin, and safranal. Through deep transcriptome analysis, we identified a novel carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CCD) whose expression profile parallels the production of crocetin. Using in bacterio, in vitro, and in planta functional assays, we demonstrate that CCD2 is the dioxygenase catalyzing the first dedicated step in saffron crocetin biosynthesis starting from the carotenoid zeaxanthin.

Keywords: β-citraurin, symmetric carotenoid cleavage

Abstract

Crocus sativus stigmas are the source of the saffron spice and accumulate the apocarotenoids crocetin, crocins, picrocrocin, and safranal, responsible for its color, taste, and aroma. Through deep transcriptome sequencing, we identified a novel dioxygenase, carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 2 (CCD2), expressed early during stigma development and closely related to, but distinct from, the CCD1 dioxygenase family. CCD2 is the only identified member of a novel CCD clade, presents the structural features of a bona fide CCD, and is able to cleave zeaxanthin, the presumed precursor of saffron apocarotenoids, both in Escherichia coli and in maize endosperm. The cleavage products, identified through high-resolution mass spectrometry and comigration with authentic standards, are crocetin dialdehyde and crocetin, respectively. In vitro assays show that CCD2 cleaves sequentially the 7,8 and 7′,8′ double bonds adjacent to a 3-OH-β-ionone ring and that the conversion of zeaxanthin to crocetin dialdehyde proceeds via the C30 intermediate 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal. In contrast, zeaxanthin cleavage dioxygenase (ZCD), an enzyme previously claimed to mediate crocetin formation, did not cleave zeaxanthin or 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal in the test systems used. Sequence comparison and structure prediction suggest that ZCD is an N-truncated CCD4 form, lacking one blade of the β-propeller structure conserved in all CCDs. These results constitute strong evidence that CCD2 catalyzes the first dedicated step in crocin biosynthesis. Similar to CCD1, CCD2 has a cytoplasmic localization, suggesting that it may cleave carotenoids localized in the chromoplast outer envelope.

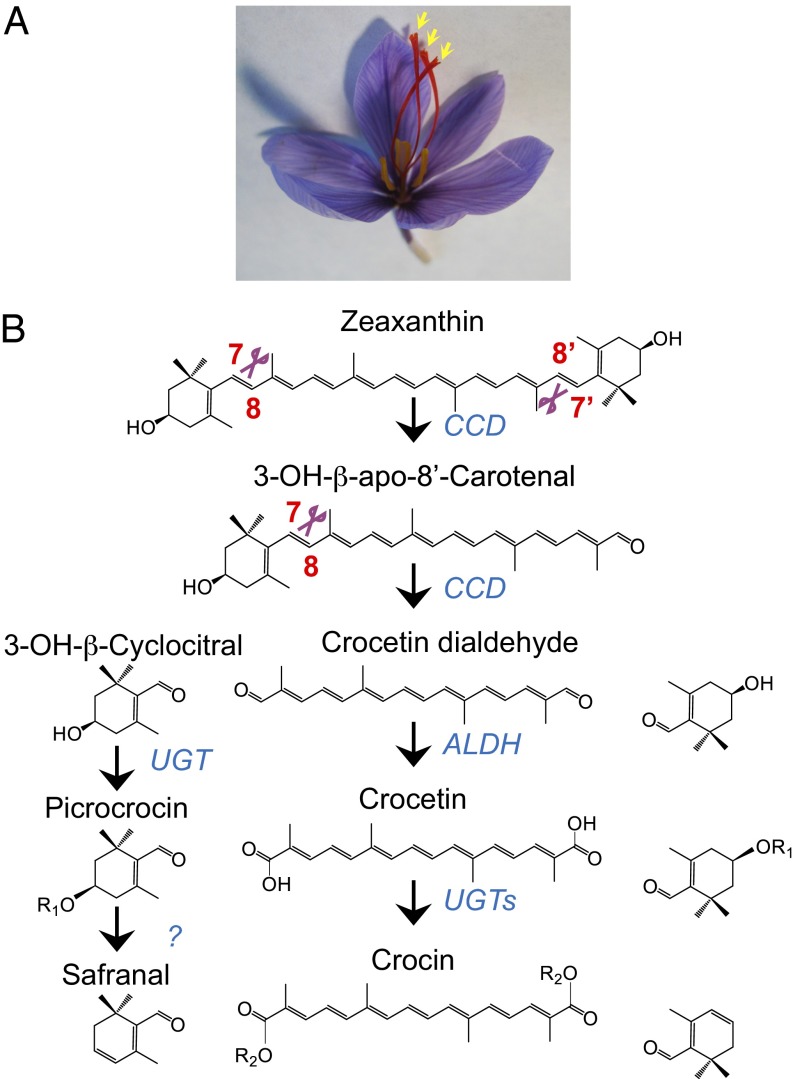

The plant Crocus sativus L. (Iridaceae) is a perennial, sterile, vegetatively propagated triploid widely cultivated in a temperate belt extending from Spain to Kashmir (1). Albeit its site of domestication is uncertain, the earliest archaeological evidence of its cultivation is provided by Minoan frescoes dated 1,700–1,500 B.C. Its dried red stigmas (Fig. 1A) constitute the saffron spice, which is commonly considered the most expensive spice on Earth, with retail prices ranging between 2,000 and 7,000 €/kg. These high prices are due to the labor associated with its harvesting: because one stigma of saffron weighs about 2 mg, 1 kg of dry saffron requires the manual harvest of stigmas from around 110,000–170,000 flowers (www.europeansaffron.eu) (1).

Fig. 1.

The saffron apocarotenoid pathway. Crocus sativus flower at anthesis. The yellow arrowheads point at the three stigmas (A). Proposed saffron apocarotenoid biosynthesis pathway (B). Zeaxanthin is cleaved at the 7,8 and 7′,8′ positions by a CCD activity. The C20 cleavage product, crocetin dialdehyde, is converted to crocetin by an aldehyde dehydrogenase, and then to crocins by at least two UDPG-glucosyltransferases. The C10 product, 3-OH-β-cyclocitral, is converted to picrocrocin by an UDPG-glucosyltransferase, and then to safranal.

Saffron stigmas accumulate large amounts (up to 8% on dry weight) of the apocarotenoids crocetin (and its glycosylated forms, crocins), responsible for the red pigmentation of the stigmas; picrocrocin, responsible for their bitter flavor; and safranal, responsible for the pungent aroma of saffron (Fig. 1A) (2). The proposed biosynthetic pathway (3, 4) starts through the symmetric cleavage of zeaxanthin at the 7,8/7′,8′ positions by a nonheme iron carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CCD) (Fig. 1B). The two cleavage products, 3-OH-β-cyclocitral and crocetin dialdehyde, are dehydrogenated and glycosylated to yield picrocrocin and crocins, respectively. Putative glucosyl transferases responsible for the synthesis of crocins have been characterized in saffron and in Gardenia (5, 6).

Plant CCDs can be classified in five subfamilies according to the cleavage position and/or their substrate preference: CCD1, CCD4, CCD7, CCD8, and nine-cis-epoxy-carotenoid dioxygenases (NCEDs) (7–9). NCEDs solely cleave the 11,12 double bond of 9-cis-epoxycarotenoids to produce the ABA precursor xanthoxin. CCD7 and CCD8 act sequentially in the strigolactone pathway, leading to strigolactone precursor carlactone (10). Enzymes of the CCD1 family cleave a wide spectrum of different carotenoids at several different positions (9,10; 9,10,9′,10′; 5,6,5′,6′; or 7,8,7′,8′) (11, 12). CCD4 enzymes cleave carotenoids at the 9′,10′ or the 7′,8′ positions and determine the level of pigmentation in plant tissues, including Chrysanthemum petals (13), peach flesh (14), potato tubers (15), Citrus peel (16, 17), and Arabidopsis seeds (18).

Structurally, all CCDs are characterized by a rigid, seven-bladed β-propeller structure, at the axis of which a Fe2+ atom is located (19). The propeller is covered by a less-conserved dome formed by a series of loops. The reaction is catalyzed by the Fe2+ atom via the introduction of oxygen (20).

To date, conflicting data have been reported about the identity of the enzyme catalyzing the cleavage reaction in saffron. A zeaxanthin cleavage dioxygenase (ZCD) was reported to cleave zeaxanthin symmetrically at the 7,8/7′,8′ positions, yielding the crocin precursor crocetin dialdehyde (4). However, later work has suggested that ZCD is a truncated form of a plastoglobule-localized CCD4 enzyme, devoid of cleavage activity, and that the full-length form cleaves β-carotene at the 9,10 and/or the 9′,10′ positions, yielding β-ionone (21).

We used deep transcriptome sequencing of six stigma stages to identify all CCDs expressed during saffron stigma development. Our work identified seven different CCD transcripts, including CCD1, three CCD4 isoforms, ZCD, CCD7, and CCD2, encoding a novel type of plant CCD. We report that CCD2 is the enzyme responsible for the cleavage step leading to crocetin biosynthesis starting from the precursor, zeaxanthin.

Results

Identification of CCD Transcripts Expressed in C. sativus Stigmas.

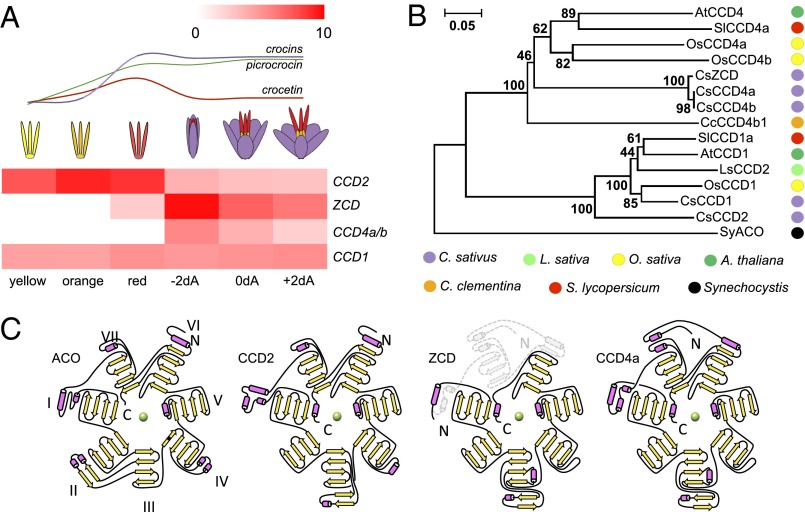

To identify the enzyme(s) responsible for the biosynthesis of saffron-specific apocarotenoids, we performed 454 transcriptome sequencing of six different stigma developmental stages: Y, yellow stigma, closed bud inside the perianth tubes (around 0.3 cm in length); O, orange stigma, closed bud inside the perianth tubes (around 0.4 mm in length); R, red stigma, closed bud inside the perianth tubes (0.8 mm in length); −2dA, 2 d before anthesis, dark red stigmas in closed bud outside the perianth tubes; 0dA, day of anthesis, dark red stigmas; +2dA, 2 d after anthesis (Fig. 2A). Crocetin and crocins start accumulating at the O stage and their biosynthesis is essentially complete at the R stage (22). Approximately 120,000 454 reads from each stage were assembled using Newbler, and the contigs were searched for similarity to known CCD enzymes using BLAST. The search resulted in seven CCDs, including CCD1, CCD7, three allelic forms of CCD4, and a novel transcript, which we called CCD2 due to its evolutionary relation with CCD1 (see below). The identified CCDs differ in their temporal pattern of expression during stigma development (Table S1). In particular, CCD2 expression peaks early, at the O stage (Fig. 2A) coincident with crocetin and crocin accumulation (22), whereas ZCD and CCD4 are expressed late during stigma development.

Fig. 2.

Expression and structural characteristics of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenases from saffron stigma. Transcript levels of saffron CCDs in different stigma developmental stages, based on 454 RNA-Seq data; −2dA, 2 d preanthesis; 0dA, day of anthesis; +2dA, 2 d postanthesis (A). Data expressed as reads per kilobase per million (RPKM). The graph above the heat map indicates the kinetics of accumulation of the different apocarotenoids. Phylogenetic relationships of CCDs from saffron (Cs), Arabidopsis (At), rice (Os), tomato (Sl), lettuce (Ls), clementine (Cc), and Synechocystis (Sy) inferred using the neighbor-joining method; CsCCD1, CAC79592.1; CsCCD4a, ACD62476.1; CsCCD4b, ACD62477.1; CsZCD, CAD33262.1; AtCCD1, AT3G63520; AtCCD4, AT4G19170; OsCCD1, Os12g0640600; OsCCD4A, Os02g0704000; OsCCD4B, Os12g0435200; SlCCD1a, Solyc01g087250.2; SlCCD4a, Solyc08g075480.2; LsCCD2, BAE72095.1; CcCCD4b1, Ciclev10028113m; SyACO, P74334 (B). Topology diagrams of Synechocystis apocarotenoid cleavage oxygenase (ACO) and Crocus sativus CCD2, ZCD, CCD4a (C). Secondary structural elements consisting of α-helices and β-sheets are colored in pink and yellow, respectively. The seven blades are labeled from I to VII for ACO and is the same for the other topology diagrams. The ferrous catalytic iron is colored in green. All structural elements located outside the seven blades form part of the dome. The gray shaded structural elements in ZCD are lacking; please note the alternative N terminus. Most of the dome is lacking in this protein, together with most of blade VII. CCD4a topology diagram is showed for comparison.

A phylogenetic analysis of CCD protein sequences from several plants was inferred using the neighbor-joining method using Synechocystis apocarotenoid cleavage oxygenase (ACO) as an outgroup (Fig. 2B). The results suggested that Crocus CCD2 is a member of a clade closely related to, but distinct from, angiosperm CCD1 enzymes. A lettuce enzyme labeled as CCD2 (23) clustered with CCD1 enzymes, whereas an enzyme known to cut zeaxanthin at the 7,8 position, Citrus CCD4b1 (16), clustered with CCD4 enzymes (Fig. 2B). ZCD appeared to be a member of the CCD4 family (Fig. 2B), truncated at the N terminus (Fig. S1).

Because the ZCD cDNA was originally isolated by rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) (4, 24) that can lead to the cloning of truncated transcripts, we carried out a 5′-RACE analysis of CCD4 transcripts. Next to a 950-base full-length transcript, whose length is compatible with a full-length CCD4 protein, a series of abundant 5′-truncated transcripts are detectable, the longest of which is compatible with the length of the ZCD protein, which is encoded starting from an internal ATG codon (Fig. S2A). It is therefore likely that the original ZCD clone (4) corresponds to a truncated CCD4 transcript. This cannot be either CCD4a or CCD4b (25), which are only 98% identical to ZCD at the nucleotide level. To further address this point, we cloned the 400- to 350-bp RACE products shown in Fig. S2A, containing the internal ATG codon, and sequenced multiple clones. The sequence of eight of the clones corresponds to CCD4a, of one to CCD4b, of five to ZCD (4), and of four to a yet-unidentified CCD4. All of them contain the internal ATG codon.

We modeled the CCD2, ZCD, and CCD4a structures using the RaptorX web server (26) based on the known crystal structure of the Synechocystis ACO (20) as a reference (Fig. 2C). The deduced models show that ZCD is an incomplete enzyme in comparison with the other CCDs predicted structures and ACO. In particular, it lacks blade VII of the β-propeller and part of the dome, whereas CCD2 displays all of the structural features of bona fide CCDs (Fig. 2C).

Saffron CCD2 Expressed in Escherichia coli Cleaves Zeaxanthin to Yield Crocetin Dialdehyde.

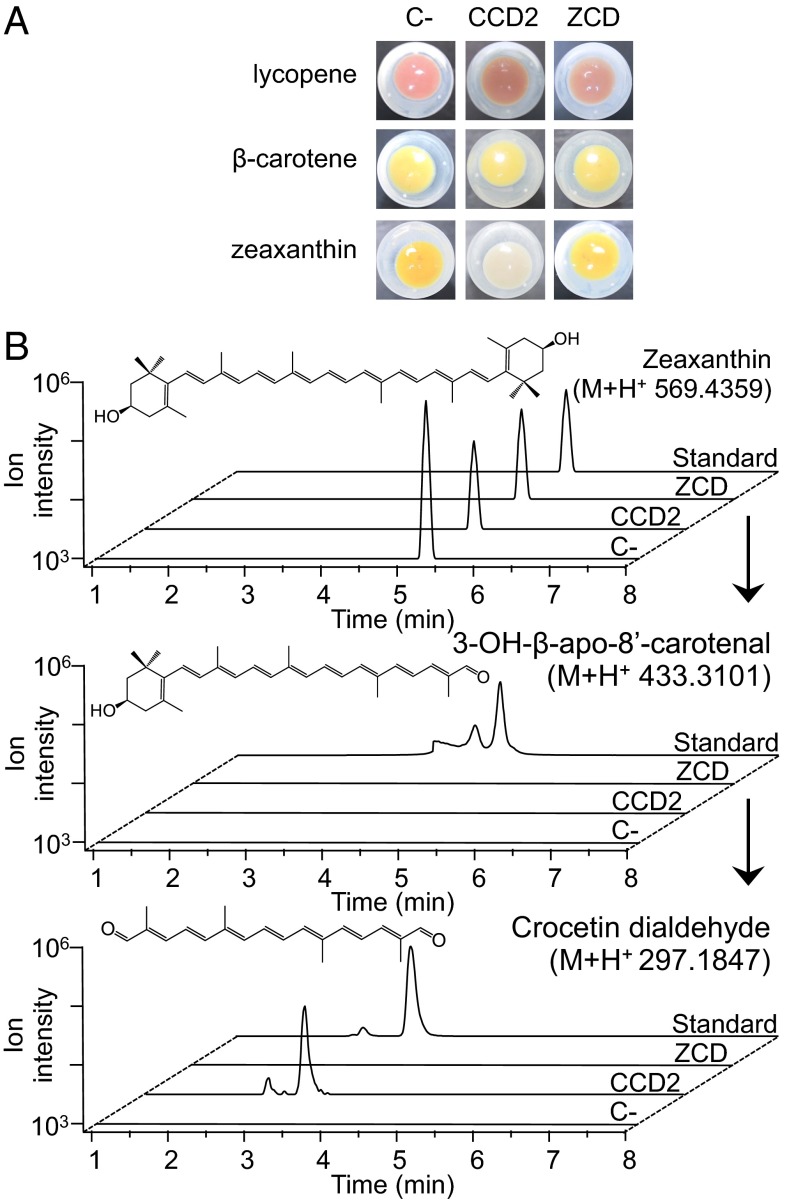

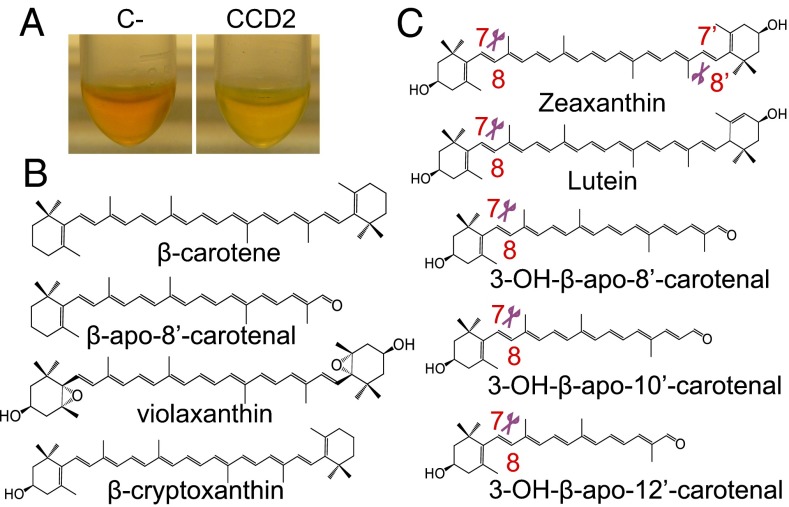

The CCD2 and ZCD coding sequences were cloned to yield thioredoxin fusion proteins in the pThio-DAN1 vector, affording arabinose-inducible expression in E. coli (27). The recombinant proteins were expressed in three genetically engineered E. coli strains, accumulating lycopene, β-carotene, and zeaxanthin, respectively (Fig. 3A) (28). SDS/PAGE analysis showed that both CCD2 and ZCD fusions were expressed with an apparent molecular mass of 81 and 59 kDa, respectively (Fig. S2B).

Fig. 3.

CCD2 expressed in E. coli cleaves zeaxanthin to yield crocetin dialdehyde. E. coli cells accumulating lycopene, β-carotene, or zeaxanthin were transformed with the empty pThio vector (C−), or the same vector expressing CCD2 or ZCD, induced for 16 h at 20 °C with arabinose and pelleted (A). Note the discoloration of zeaxanthin in CsCCD2-expressing cells. LC-HRMS analysis of zeaxanthin cleavage products (B). Zeaxanthin-accumulating E. coli cells expressing CsCCD2 were induced for 16 h at 20 °C with arabinose, extracted with acetone, and the extracts were run on a LC-HRMS system alongside authentic standards. The accurate masses of zeaxanthin, 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal, and crocetin dialdehyde were extracted. Only crocetin dialdehyde is detectable and has an accurate mass and a chromatographic mobility identical to that of the authentic standard.

No decoloration was observed in E. coli strains accumulating lycopene or β-carotene upon expression of CCD2 or ZCD (Fig. 3A), and no cleavage product was detected in these strains (Fig. S3). In contrast, CCD2 expression in zeaxanthin accumulating E. coli cells led to evident decoloration (Fig. 3A). Analysis by HPLC coupled with high-resolution mass spectrometry (LC-HRMS) revealed a new peak with an m/z of 297.1847 corresponding to the protonated C20-dialdehyde 8,8′-diapocarotene-8,8′-dial (crocetin dialdehyde) that coeluted with the authentic standard (Fig. 3B). We therefore concluded that CCD2 cleaves zeaxanthin symmetrically at the 7,8/7′,8′ positions to yield crocetin dialdehyde. ZCD showed no decoloration and no detectable cleavage products in any of the strains (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3).

Saffron CCD2 Expressed in Maize Endosperm Cleaves Zeaxanthin to Yield Crocetin.

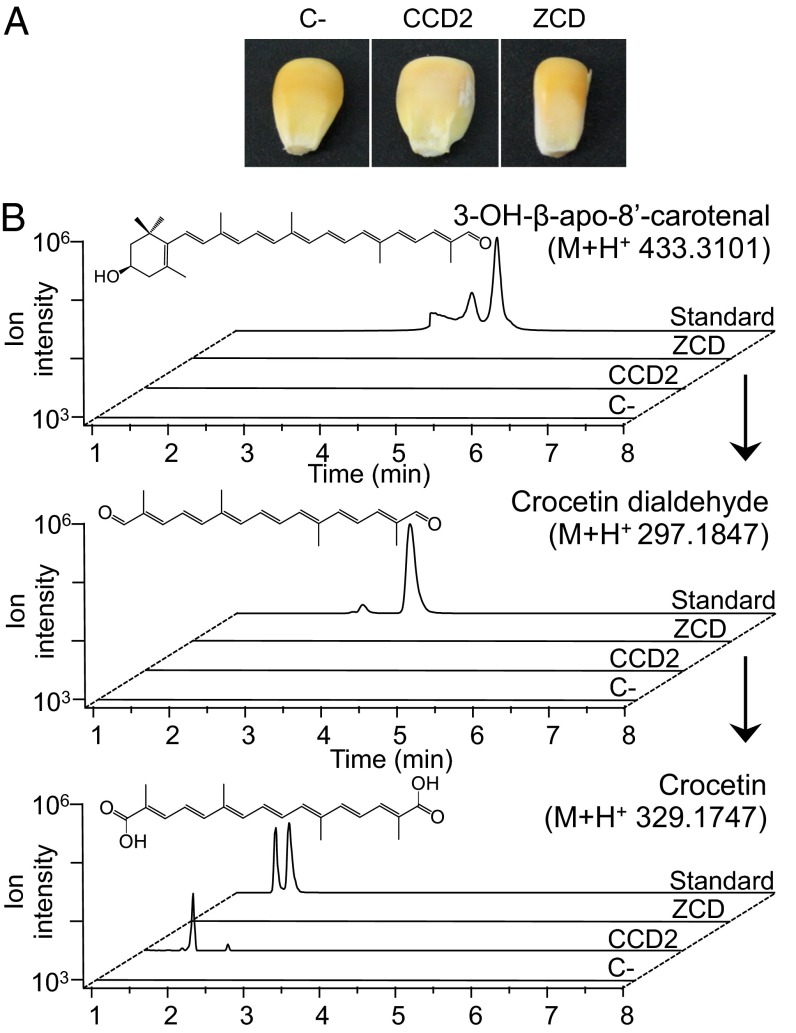

To investigate the cleavage activity of CCD2 and ZCD in planta, we used Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression (29) in yellow maize endosperm, which is known to accumulate several xanthophylls, including zeaxanthin. The CCD2 and ZCD coding sequences were cloned into a binary vector under the control of 35S promoter. A vector containing the intron-bearing β-glucuronidase reporter gene (p35S:GUS_INT:NOS) (30) was used to optimize the transformation protocol (Table S2) and as a control for transformation efficiency. Fig. 4A shows pictures of maize kernels transformed with the three constructs. Kernels transformed with CCD2 show decoloration, compared with those transformed with the control plasmid or ZCD. Analysis of the CCD2-expressing samples by quantitative LC-HRMS (Fig. 4B) showed neither the cleavage intermediate 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal (β-citraurin) nor the final product crocetin dialdehyde (Fig. 4B). However, we identified a new peak with an m/z of 329.1747 expected for crocetin that was chromatographically indistinguishable from an authentic crocetin standard. Thus, contrary to E. coli, maize endosperm most likely possesses an endogenous aldehyde dehydrogenase, allowing this crocetin dialdehyde oxidation step. This product was not detectable in endosperm overexpressing ZCD or GUS_INT (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Cleavage of maize kernel carotenoids by transiently expressed CCD2. Pigmentation of maize kernels after 48 h of agroinfiltration with pBI-GUS, pBI-CCD2, and pBI-ZCD (A). LC-HRMS of hydrophobic kernel extracts (B). The CCD2 extracts show accumulation of crocetin, but not crocetin dialdehyde or 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal.

LC-HRMS of carotenoids of transformed maize kernels revealed significant decreases in the content of both zeaxanthin and lutein, but not in that of β-cryptoxanthin, indicating that also lutein may be a CCD2 substrate (Table 1).

Table 1.

Normalized ion peak areas

| Compound | Control | CCD2 | ZCD |

| Lutein | 0.81 ± 0.15 | 0.48 ± 0.05* | 0.64 ± 0.09 |

| Zeaxanthin | 1.98 ± 0.33 | 0.84 ± 0.18* | 1.73 ± 0.20 |

| β-Cryptoxanthin | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.04 |

| Crocetin | n.d. | 0.008 ± 0.002 | n.d. |

Ion peak areas, normalized for the internal standard, for the main kernel carotenoids and apocarotenoids. Data are the average ± SD of four biological replicates. n.d., not detectable; *P value, 0.01.

In Vitro Substrate Specificity of Saffron CCD2.

Because only a limited number of carotenoids can be produced in genetically engineered E. coli, we used an in vitro assay to explore the substrate specificities and regional cleavage specificities of CCD2 and ZCD (Fig. 5). In the in vitro assay, CCD2 did not convert β-carotene, violaxanthin, β-apo-8′-carotenal, or β-cryptoxanthin (Fig. S4), but it cleaved zeaxanthin yielding a C30 apocarotenoid identified on the basis of its m/z and its chromatographic identity with the authentic standard, as 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal (β-citraurin) (Fig. S5 A and B), i.e., the product of a single cleavage at the 7′,8′ position. ZCD did not convert any of the substrates tested, including zeaxanthin (Fig. S5A).

Fig. 5.

In vitro cleavage assay. In vitro cleavage of zeaxanthin by E. coli extracts (A). Decoloration is diagnostic of cleavage. Cleavage products are identified by HPLC–photodiode array detection (HPLC-PDA) and LC-HRMS (Fig. S5A). Substrates that are not cleaved by CCD2 in the in vitro assay (B). Substrates that are cleaved by CCD2 in the in vitro assay and position of the cleavage, as deduced by HPLC-PDA or Orbitrap LC-HRMS analysis (C) (Figs. S5 and S6). The percentage cleavage of the different substrates in an overnight assay is shown in Table S3.

We also tested whether the product 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal, formed by CCD2 from zeaxanthin in vitro, can as well be a substrate. Indeed, the formation of crocetin dialdehyde and crocetin was observed (Fig. S5C). This suggests that 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal is a substrate of CCD2 and that the conversion of zeaxanthin to crocetin dialdehyde likely occurs in two sequential steps. Furthermore, E. coli seems to contain an aldehyde dehydrogenase activity that is not active in vivo, but partially activated in vitro.

CCD2 cleaved also lutein (Fig. S6 A and B), yielding a C30 apocarotenoid with a chromatographic mobility different from that of 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal. Despite the unavailability of an authentic standard, this compound could be identified unambiguously as 3-OH-ε-apo-8′-carotenal on the basis of its m/z of 415.2981, indicative of the loss of a water molecule (432.3028 + [H]+ − [H2O]). Molecules that have an OH group at an allylic position, such as the 3 position of an ε-ionone ring, readily eliminate one molecule of water upon ionization (31). The above results suggest that the CCD2 cleavage site is always at the 7,8 position adjacent to the 3-OH-β-ionone ring (Fig. 5). CCD2 cleaved also 3-OH-β-apo-10′-carotenal (C27) and 3-OH-β-apo-12′-carotenal (C25) (Fig. 5 and Fig. S6 C and D), yielding a C17- and a C15-dialdehyde, respectively. This indicates that CCD2 is regiospecific, always targeting the C7–C8 double bond and tolerating variations in the length of the apocarotenal polyene moiety.

To assess the affinity of CCD2 for its different substrates, we measured the percentage conversion rates of these substrates in the in vitro assay (Table S3). Although the data are only semiquantitative, due to the differential solubility of the different substrates, 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal showed the highest (52.7%) conversion rate, followed by 3-OH-β-apo-12′- and 3-OH-β-apo-10′-carotenal (18.5% and 12.5%, respectively). Zeaxanthin and lutein showed the lowest (4.8% and 1.7%, respectively) conversion rates among the cleaved substrates.

Subcellular Localization of Saffron CCD2.

Based on ChloroP analysis, CsCCD2 lacks a recognizable plastid transit peptide (Fig. S1). Because as many as 12% of chloroplast-localized proteins present this feature (32), we studied the localization of a C-terminal fusion of CCD2 to green fluorescent protein (CCD2:GFP) in Nicotiana benthamiana-agroinfiltrated leaves. The results (Fig. S7) suggest that CCD2:GFP is a cytoplasmic protein.

Discussion

Using deep transcriptome analysis of developing saffron stigmas, we have identified a novel CCD enzyme, CCD2, expressed during early stigma development, consistent with the time course of crocetin formation. Analysis of the amino acid sequences of several CCDs belonging to saffron, Arabidopsis, lettuce, Citrus, rice, and cyanobacteria indicates that saffron CCD2 represents a novel branch close to, but distinct from the CCD1 family. CCD1 enzymes are known to cleave carotenoids, linear and cyclic, at several bonds (9,10; 9,10,9′,10′; 5,6,5′,6′; or 7,8,7′,8′) (33).

On the basis of the evidence presented, we suggest that CCD2 is the enzyme that catalyzes the zeaxanthin cleavage step in crocetin biosynthesis. The previously described ZCD enzyme (4) appears to be an N-truncated form of a CCD4 enzyme, encoded by a 5′-truncated CCD4 transcript distinct from both CCD4a and CCD4b (25). This truncated enzyme was inactive in all of our in vivo and in vitro assays.

In contrast to ZCD, CCD2 displays all of the structural features of a bona fide CCD. It is highly expressed at the orange stage of stigma development, when crocetin accumulation is maximal, and when expressed in E. coli, it is able to convert zeaxanthin to crocetin dialdehyde via two sequential cleavage reactions at the 7,8 and 7′,8′ positions. In vivo expression in maize kernels and in vitro assays confirm this activity and provide evidence for the subsequent conversion of crocetin dialdehyde to crocetin, probably through the action of nonspecific maize aldehyde dehydrogenases.

Like the related CCD1 enzymes (21, 34), CCD2 lacks a recognizable plastid transit peptide and is localized to the cytoplasm. Carotenoids are synthesized in plastids and are found in several plastid compartments, including the outer envelope, which is particularly rich in xanthophylls (35). Therefore, a likely hypothesis is that CCD2 transiently associates with the outer envelope of saffron stigma chromoplasts and cleaves the xanthophylls localized in it.

The first CCD 3D structure was obtained from ACO, a cyanobacterial enzyme synthesizing the C20 apocarotenoid retinal (20). The protein structure revealed that the enzyme contains a Fe2+ ion in the active site, coordinated by four conserved histidine residues, an arrangement common to all CCDs. The iron in ACO is encased by a rigid, seven-bladed β-propeller structure, overarched by a dome of six large loops (Fig. 2C). The β-propeller portion of the structure is present in all CCDs characterized to date, from bacteria to animals to plants (19). To understand the differences between the here-identified CCD2 and ZCD, we modeled the tertiary structure using ACO as template (Fig. 2C). This revealed that ZCD lacks blade VII of the propeller [known to participate in the coordination of the central iron atom (19)] and part of the dome. 5′-RACE experiments (Fig. S2A), suggest that ZCD is encoded by a truncated CCD4 transcript, leading to a nonfunctional protein. All assays aimed at uncovering a cleavage activity of ZCD, in bacterio, in planta, and in vitro, were met with negative results. This is consistent with the observation made by Rubio et al. (21) with the CCD4a-211 truncated enzyme, which is almost identical to ZCD.

Our results confirm the pathway proposed for saffron apocarotenoid biosynthesis (3, 4) in two important aspects: zeaxanthin is a substrate for the cleavage reaction and the cleavage occurs at the 7,8 and 7′,8′ positions. The in vitro assays indicate that the cleavage reaction occurs in two subsequent steps: a first cleavage generates 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal, which is then recleaved by the same enzyme to yield crocetin dialdehyde. We envisage two possible mechanisms through which this double cleavage can occur: (i) a sliding mechanism, in which the carotenoid molecule is bound in the hydrophobic tunnel in a position that brings the catalytic iron close to the 7,8 double bond, and then, after the first cleavage has occurred, it slides to bring the iron close to the 7′,8′ double bond for the second cleavage; or (ii) a flipping mechanism, in which after the first cleavage the apocarotenoid exits the tunnel and reenters it in the opposite orientation, to be cleaved at the symmetric position. We favor the second mechanism, in view of the fact that 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal is accumulated in free form in the in vitro reaction.

The combined data obtained in bacterio, in planta, and in vitro give a rather precise idea of the steric requirements of CCD2 for its substrate: CCD2 cleaves zeaxanthin, lutein, and all tested 3-OH-β-apocarotenals at the 7,8 position, but it does not cleave β-carotene and lycopene, indicating an absolute requirement for 3-OH-β-ring at the proximal end of the molecule. The distal end of the molecule can be a 3′-OH-β- or ε-ring or an aldehyde moiety because zeaxanthin, lutein, and 3-OH-β-apocarotenals of varying lengths are accepted substrates. However, the in planta and in vitro data suggest that some constraints exist also for the distal end, because β-cryptoxanthin, which has an unsubstituted β-ring at the distal end, is not cleaved by CCD2. We measured the percentage conversion of the various substrates in the in vitro assay. The results indicate that zeaxanthin and 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal are the preferred substrates, respectively, for the first and second cleavage reaction. The very high conversion of 3-OH-β-apo-8′-carotenal provides an explanation for the fact that this intermediate is not accumulated in bacterio or in planta.

Although the principal objective of this study, i.e., the identification of the enzyme catalyzing the initial cleavage step in the saffron apocarotenoid pathway and the characterization of its activity, has been met, the enzymatic steps downstream of the cleavage step still await complete elucidation. Several aldehyde dehydrogenases and glucosyl transferases have been identified in our transcriptome data and hold promise for a complete reconstruction of the saffron apocarotenoid pathway.

Materials and Methods

454 Titanium RNA-Seq sequencing of saffron stigma DNAs was performed according to published methods (36) and will be reported elsewhere. The sequence of CCD2 has been submitted to GenBank under accession number KJ541749. Evolutionary relationships were inferred using the neighbor-joining method (37), and evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA5 (38). Heat maps were created using Genesis (39). CCD models were drawn with the RaptorX web server (26). Chloroplast transit peptides were deduced using ChloroP (40). 5′-RACE was performed using a commercial kit (Life Technologies; catalog number 18374-058). In bacterio assays were performed using E. coli strains accumulating lycopene, β-carotene, zeaxanthin (28, 41), and CCD2 or ZCD expressed in the pTHIO-DAN1 expression vector (27). For in vitro assays, the expression vectors were transformed into E. coli BL21 (pGro7) (Takara); crude lysates were prepared, incubated with appropriate substrates, and extracted as described (41). Carotenoid/apocarotenoid analysis was performed on an LTQ-Orbitrap mass spectrometry system coupled to an Accela U-HPLC system equipped with a photodiode array detector (ThermoFisher Scientific) using positive mode atmospheric pressure chemical ionization and a C30 reverse-phase column (31). Ion peak areas were normalized to the internal standard (α-tocopherol acetate). For transient transformation of maize kernels, CCD2 was cloned in the pBI121 vector (42) and transformed using a published method (29). For subcellular localization, CCD2 was fused C-terminally to enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) (43) using Gibson assembly (44) and agroinfiltrated in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves as described (45). After 48 h, leaves were analyzed by confocal laser-scanning microscopy. Green and red fluorescence were used to detect eGFP and chlorophyll signals, respectively. A detailed description of all materials and methods used is provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Hansgeorg Ernst for providing the synthetic substrates; Chiara Lico for a gift of N. benthamiana plants and for help in agroinfiltration experiments; Elena Romano and Emanuela Viaggiu at the Centre of Advanced Microscopy “Patrizia Albertano” for the confocal images; Gaetano Perrotta, Paolo Facella, and Fabrizio Carbone for 454 sequencing; and Alessia Fiore for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Research (Project “Integrated Knowledge for the Sustainability and Innovation of Italian Agri-Food”), German Research Foundation (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) Grant AL 892/1-4, the European Union [The development of tools and effective strategies for the optimisation of useful secondary metabolite production in planta, Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) Contract 244348; From discovery to products: A next generation pipeline for the sustainable generation of high-value plant products, FP7 Contract 613153], the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (BIO2009-07803), and the Iberoamerican Network for the Study of Carotenoids as Food Ingredients (112RT0445). S.F. was supported by short-term fellowships of the PlantEngine (FA1006) and Saffronomics (FA1101) European Cooperation in Science and Technology actions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The sequence of CCD2 reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. KJ541749).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1404629111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fernandez JA, Pandalai SG. Biology, biotechnology and biomedicine of saffron. Recent Res Dev Plant Sci. 2004;2:127–159. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caballero-Ortega H, Pereda-Miranda R, Abdullaev FI. HPLC quantification of major active components from 11 different saffron (Crocus sativus L.) sources. Food Chem. 2007;100(3):1126–1131. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfander H, Schurtenberger H. Biosynthesis of C20-carotenoids in Crocus sativus. Phytochemistry. 1982;21(5):1039–1042. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouvier F, Suire C, Mutterer J, Camara B. Oxidative remodeling of chromoplast carotenoids: Identification of the carotenoid dioxygenase CsCCD and CsZCD genes involved in Crocus secondary metabolite biogenesis. Plant Cell. 2003;15(1):47–62. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moraga AR, Nohales PF, Pérez JA, Gómez-Gómez L. Glucosylation of the saffron apocarotenoid crocetin by a glucosyltransferase isolated from Crocus sativus stigmas. Planta. 2004;219(6):955–966. doi: 10.1007/s00425-004-1299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagatoshi M, et al. UGT75L6 and UGT94E5 mediate sequential glucosylation of crocetin to crocin in Gardenia jasminoides. FEBS Lett. 2012;586(7):1055–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giuliano G, Al-Babili S, von Lintig J. Carotenoid oxygenases: Cleave it or leave it. Trends Plant Sci. 2003;8(4):145–149. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00053-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Auldridge ME, McCarty DR, Klee HJ. Plant carotenoid cleavage oxygenases and their apocarotenoid products. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9(3):315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walter MH, Strack D. Carotenoids and their cleavage products: Biosynthesis and functions. Nat Prod Rep. 2011;28(4):663–692. doi: 10.1039/c0np00036a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alder A, et al. The path from β-carotene to carlactone, a strigolactone-like plant hormone. Science. 2012;335(6074):1348–1351. doi: 10.1126/science.1218094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vogel JT, Tan BC, McCarty DR, Klee HJ. The carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 enzyme has broad substrate specificity, cleaving multiple carotenoids at two different bond positions. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(17):11364–11373. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710106200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ilg A, Beyer P, Al-Babili S. Characterization of the rice carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase 1 reveals a novel route for geranial biosynthesis. FEBS J. 2009;276(3):736–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohmiya A, Kishimoto S, Aida R, Yoshioka S, Sumitomo K. Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase (CmCCD4a) contributes to white color formation in chrysanthemum petals. Plant Physiol. 2006;142(3):1193–1201. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.087130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brandi F, et al. Study of “Redhaven” peach and its white-fleshed mutant suggests a key role of CCD4 carotenoid dioxygenase in carotenoid and norisoprenoid volatile metabolism. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell R, et al. The metabolic and developmental roles of carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase4 from potato. Plant Physiol. 2010;154(2):656–664. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.158733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodrigo MJ, et al. A novel carotenoid cleavage activity involved in the biosynthesis of Citrus fruit-specific apocarotenoid pigments. J Exp Bot. 2013;64(14):4461–4478. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma G, et al. Enzymatic formation of β-citraurin from β-cryptoxanthin and Zeaxanthin by carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase4 in the flavedo of citrus fruit. Plant Physiol. 2013;163(2):682–695. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.223297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez-Jorge S, et al. Carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase4 is a negative regulator of β-carotene content in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell. 2013;25(12):4812–4826. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.119677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sui X, Kiser PD, Lintig Jv, Palczewski K. Structural basis of carotenoid cleavage: From bacteria to mammals. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2013;539(2):203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kloer DP, Ruch S, Al-Babili S, Beyer P, Schulz GE. The structure of a retinal-forming carotenoid oxygenase. Science. 2005;308(5719):267–269. doi: 10.1126/science.1108965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubio A, et al. Cytosolic and plastoglobule-targeted carotenoid dioxygenases from Crocus sativus are both involved in beta-ionone release. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(36):24816–24825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moraga AR, Rambla JL, Ahrazem O, Granell A, Gómez-Gómez L. Metabolite and target transcript analyses during Crocus sativus stigma development. Phytochemistry. 2009;70(8):1009–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawada Y, et al. Phytochrome- and gibberellin-mediated regulation of abscisic acid metabolism during germination of photoblastic lettuce seeds. Plant Physiol. 2008;146(3):1386–1396. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.115162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frohman MA, Dush MK, Martin GR. Rapid production of full-length cDNAs from rare transcripts: Amplification using a single gene-specific oligonucleotide primer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(23):8998–9002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.8998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahrazem O, Trapero A, Gómez MD, Rubio-Moraga A, Gómez-Gómez L. Genomic analysis and gene structure of the plant carotenoid dioxygenase 4 family: A deeper study in Crocus sativus and its allies. Genomics. 2010;96(4):239–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Källberg M, et al. Template-based protein structure modeling using the RaptorX web server. Nat Protoc. 2012;7(8):1511–1522. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trautmann D, Beyer P, Al-Babili S. The ORF slr0091 of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 encodes a high-light induced aldehyde dehydrogenase converting apocarotenals and alkanals. FEBS J. 2013;280(15):3685–3696. doi: 10.1111/febs.12361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prado-Cabrero A, Scherzinger D, Avalos J, Al-Babili S. Retinal biosynthesis in fungi: Characterization of the carotenoid oxygenase CarX from Fusarium fujikuroi. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6(4):650–657. doi: 10.1128/EC.00392-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reyes FC, Sun B, Guo H, Gruis DF, Otegui MS. Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of maize endosperm as a tool to study endosperm cell biology. Plant Physiol. 2010;153(2):624–631. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.154930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vancanneyt G, Schmidt R, O’Connor-Sanchez A, Willmitzer L, Rocha-Sosa M. Construction of an intron-containing marker gene: Splicing of the intron in transgenic plants and its use in monitoring early events in Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;220(2):245–250. doi: 10.1007/BF00260489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fantini E, Falcone G, Frusciante S, Giliberto L, Giuliano G. Dissection of tomato lycopene biosynthesis through virus-induced gene silencing. Plant Physiol. 2013;163(2):986–998. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.224733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armbruster U, et al. Chloroplast proteins without cleavable transit peptides: Rare exceptions or a major constituent of the chloroplast proteome? Mol Plant. 2009;2(6):1325–1335. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssp082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walter MH, Floss DS, Strack D. Apocarotenoids: Hormones, mycorrhizal metabolites and aroma volatiles. Planta. 2010;232(1):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00425-010-1156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auldridge ME, et al. Characterization of three members of the Arabidopsis carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase family demonstrates the divergent roles of this multifunctional enzyme family. Plant J. 2006;45(6):982–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Markwell J, Bruce BD, Keegstra K. Isolation of a carotenoid-containing sub-membrane particle from the chloroplastic envelope outer membrane of pea (Pisum sativum) J Biol Chem. 1992;267(20):13933–13937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alagna F, et al. Comparative 454 pyrosequencing of transcripts from two olive genotypes during fruit development. BMC Genomics. 2009;10(1):399. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4(4):406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamura K, et al. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sturn A, Quackenbush J, Trajanoski Z. Genesis: Cluster analysis of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2002;18(1):207–208. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, von Heijne G. ChloroP, a neural network-based method for predicting chloroplast transit peptides and their cleavage sites. Protein Sci. 1999;8(5):978–984. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.5.978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alder A, Holdermann I, Beyer P, Al-Babili S. Carotenoid oxygenases involved in plant branching catalyse a highly specific conserved apocarotenoid cleavage reaction. Biochem J. 2008;416(2):289–296. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jefferson RA. Assaying chimeric genes in plants: The GUS gene fusion system. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 1987;5(4):387–405. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang TT, Cheng L, Kain SR. Optimized codon usage and chromophore mutations provide enhanced sensitivity with the green fluorescent protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24(22):4592–4593. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gibson DG, et al. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6(5):343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamilton AJ, Baulcombe DC. A species of small antisense RNA in posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants. Science. 1999;286(5441):950–952. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.