This phase III study, ACTS-CC, is the first study in which demonstrated the efficacy of S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine, as adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer by confirming its noninferiority to UFT/LV in terms of disease-free survival. S-1 could be a new treatment option as adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer.

Keywords: adjuvant chemotherapy, colon cancer, S-1, UFT/LV

Abstract

Background

S-1 is an oral fluoropyrimidine whose antitumor effects have been demonstrated in treating various gastrointestinal cancers, including metastatic colon cancer, when administered as monotherapy or in combination chemotherapy. We conducted a randomized phase III study investigating the efficacy of S-1 as adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer by evaluating its noninferiority to tegafur–uracil plus leucovorin (UFT/LV).

Patients and methods

Patients aged 20–80 years with curatively resected stage III colon cancer were randomly assigned to receive S-1 (80–120 mg/day on days 1–28 every 42 days; four courses) or UFT/LV (UFT: 300–600 mg/day and LV: 75 mg/day on days 1–28 every 35 days; five courses). The primary end point was disease-free survival (DFS) at 3 years.

Results

A total of 1518 patients (758 and 760 in the S-1 and UFT/LV group, respectively) were included in the full analysis set. The 3-year DFS rate was 75.5% and 72.5% in the S-1 and UFT/LV group, respectively. The stratified hazard ratio for DFS in the S-1 group compared with the UFT/LV group was 0.85 (95% confidence interval: 0.70–1.03), demonstrating the noninferiority of S-1 (noninferiority stratified log-rank test, P < 0.001). In the subgroup analysis, no significant interactions were identified between the major baseline characteristics and the treatment groups.

Conclusion

Adjuvant chemotherapy using S-1 for stage III colon cancer was confirmed to be noninferior in DFS compared with UFT/LV. S-1 could be a new treatment option as adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer.

ClinicalTrials.gov

introduction

Postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage III colon cancer is internationally regarded as a standard care for improving survivals. While Western guidelines recommend i.v. 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and folic acid (leucovorin, LV) or capecitabine combined with oxaliplatin (FOLFOX or CapeOX) as the first choice for adjuvant chemotherapy in stage III colon cancer [1–4], fluoropyrimidine alone remains one of the options [3, 4].

In Japan, oral fluoropyrimidine derivatives have been preferred because of their convenience, leading to the development of several oral fluoropyrimidine derivatives with different properties. Tegafur–uracil (UFT, Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) is a combination drug comprising tegafur, a prodrug of 5-FU, and uracil, an inhibitor of the 5-FU-degrading enzyme, dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD), in a molar ratio of 1 : 4. Both the NSABP C-06 trial conducted in the United States [5] and the JCOG0205 study conducted in Japan [6] demonstrated the noninferiority of UFT/LV to i.v. 5-FU/LV as adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III disease. UFT/LV is one of the commonly used regimens in adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III patients in Japan.

S-1 (Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd) is another oral fluoropyrimidine approved in Japan for various cancers including colorectal cancer, and for gastric cancers in a total of 38 countries (Asia and Europe). It combines tegafur, gimeracil, and oteracil in a molar ratio of 1 : 0.4 : 1. Gimeracil, a DPD inhibitor, is ∼180-fold more potent than uracil. Oteracil inhibits the conversion of 5-FU to active metabolites in the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in reduction of the gastrointestinal toxicity [7]. Phase III studies have demonstrated that combination with S-1 and other cytotoxic agents, such as cisplatin in advanced gastric cancer and irinotecan and oxaliplatin in advanced colorectal cancer, is noninferior to conventional 5-FU-based regimens [7, 8]. Regarding adjuvant chemotherapy, postoperative S-1 treatment significantly improved survival in patients with gastric cancer and pancreatic cancer [7, 9]. Additionally, S-1 has some potential advantages including lower drug cost compared with UFT/LV, and reported lower frequency of hand–foot syndrome (HFS) compared with capecitabine [7]. However, the efficacy of S-1 as adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer has not been established.

We therefore conducted an open-label, multicenter, randomized, controlled noninferiority study, ACTS-CC, to evaluate the noninferiority of S-1 to UFT/LV and thereby confirm the usefulness of S-1 in the adjuvant setting for stage III colon cancer. The results of safety analysis have been previously reported [10]. This paper focuses on disease-free survival (DFS) as the primary end point.

patients and methods

patients

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Research, and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each participating institute. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment.

The main inclusion criteria were as follows: age 20–80 years, histologically confirmed stage III colon adenocarcinoma after curative surgery, performance status of 0–1, no prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy for colon cancer, no other active malignancy, adequate oral intake, and preserved major organ function.

randomization and masking

Random assignment was carried out centrally; a minimization algorithm was used to maintain a 1 : 1 (S-1 : UFT/LV) treatment balance within each institute and within lymph node (LN) metastasis strata (N1 or N2 in UICC-TNM 7th classification). Treatment assignment was not masked from investigators or patients.

protocol treatment

In the S-1 group, S-1 was orally administered at a dose corresponding to the body surface area (BSA) (40 mg with BSA <1.25 m2; 50 mg with BSA 1.25–1.50 m2; 60 mg with BSA >1.50 m2) twice daily after meals for 28 consecutive days, followed by a 14-day rest. A total of four courses (24 weeks) were administered.

In the UFT/LV group, UFT (300 mg with BSA <1.17 m2, 400 mg with BSA 1.17–1.49 m2, 500 mg with BSA 1.50–1.83 m2, 600 mg with BSA >1.83 m2) and LV (75 mg/body) were administered orally in three divided doses (every 8 h) more than 1 h before or after meals for 28 consecutive days, followed by a 7-day rest. A total of five courses (25 weeks) were administered.

Assigned treatment was started within 8 weeks after surgery. Additional details, i.e. dose modifications, were provided previously [10].

follow-up

After completion of the protocol treatment, patients were followed-up according to a predefined surveillance schedule until recurrence, other malignancies, or death was confirmed. The surveillance schedule included serum tumor marker test every 3 months for 3 years and then every 6 months for up to 5 years; chest and abdominal computed tomography every 6 months for 5 years; and colonoscopy at 1, 3, and 5 years after surgery. Recurrence was confirmed on the basis of imaging studies.

DFS was defined as the time from randomization to recurrence, other malignancies, or death, whichever occurred first. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from randomization to death from any cause.

statistical design and analysis

The primary objective of the study was to demonstrate the noninferiority of S-1 to UFT/LV in terms of DFS. Based on the results reported by the Japanese clinical trial and cancer registry [11, 12], the 3-year DFS rate was assumed to be 75.0% in both groups. The steering committee deemed that a 6% lower 3-year DFS rate for S-1 than for UFT/LV would be clinically acceptable as the lower limit for noninferiority; this corresponded to a hazard ratio (HR) noninferiority margin of 1.29. With a type 1 error of ≤5% in the one-sided test and a power of ≥80%, considering an accrual period of 15 months, the required number of DFS events and patients was estimated to be 381 and 1436 per study, respectively [13]. A target sample size of 1480 was determined in consideration of a 3% drop-out rate.

Primary analysis was carried out using a data cutoff at 3 years after enrollment of the last patient (data cutoff date: 5 October 2012). Primary comparisons were based on the intention-to-treat principle, with data of the full analysis set. DFS curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the noninferiority log-rank test with stratification by LN metastasis (N1/N2) was carried out with a one-sided significance level of 0.05 [14]. The HR for DFS and its confidence interval (CI) were calculated using a stratified Cox proportional hazard model with LN metastasis (N1/N2) as stratification factor. In addition, the HR adjusted with key baseline factors using a multivariate Cox regression model was also estimated. Subgroup analysis was carried out using a Cox proportional hazard model with baseline patient characteristics, treatment groups, and these corresponding interaction terms. Secondarily, OS was analyzed in the same manner as DFS. With a median follow-up of 3 years, it was too early to compare OS, and only descriptive analysis of OS is presented in this paper. Updated survival data will be open in 2015. Data were analyzed using the SAS version 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and R version 2.13.0 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

results

patient characteristics

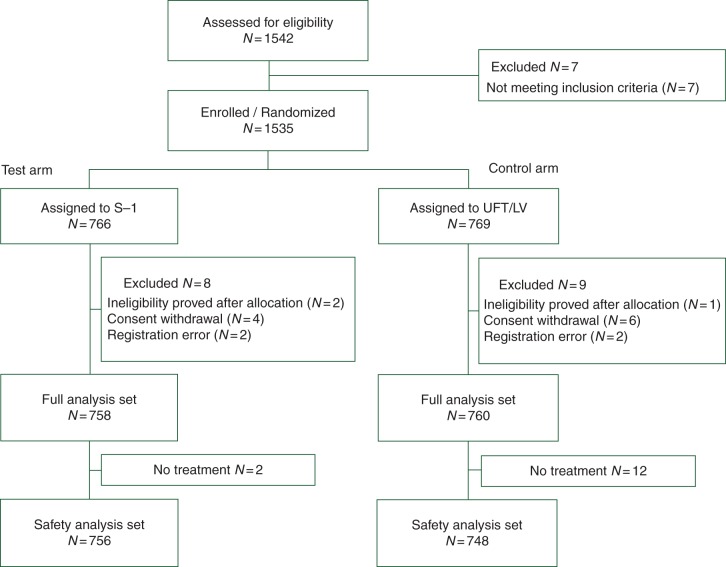

From April 2008 to June 2009, 1535 patients were enrolled from 358 hospitals in Japan. After excluding 17 patients who were found to be ineligible, 1518 were included in the full analysis set (758 and 760 in the S-1 and UFT/LV group, respectively) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram.

The median age at enrollment was 66 years, and 35.3% patients were ≥70 years. Wide LN dissection (D3 in the Japanese Classification [15]) was carried out in 79.8% patients, and the median number of LNs examined was 17. Regarding the number of metastatic LNs, 78.6% patients had one to three positive nodes, and the median was 2. The TNM-stage distribution was similar in the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 1518)

| S-1 |

UFT/LV |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 758 | % | N = 760 | % | |

| Age | ||||

| Median [range] | 66.0 [23–80] | 65.5 [32–80] | ||

| ≥70 years | 279 | 36.8 | 257 | 33.8 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 411 | 54.2 | 403 | 53.0 |

| Female | 347 | 45.8 | 357 | 47.0 |

| PS (ECOG) | ||||

| 0 | 722 | 95.3 | 727 | 95.7 |

| 1 | 36 | 4.7 | 33 | 4.3 |

| BMI | ||||

| Median [range] | 21.9 [13.2–32.4] | 22.1 [14.1–33.9] | ||

| Tumor location | ||||

| Right-sided colon | 324 | 42.7 | 268 | 35.3 |

| Left-sided colon | 278 | 36.7 | 314 | 41.3 |

| Rectosigmoid colon | 156 | 20.6 | 178 | 23.4 |

| Preoperative CEA level | ||||

| ≤5 ng/ml | 470 | 62.0 | 499 | 65.7 |

| >5 ng/ml | 261 | 34.4 | 242 | 31.8 |

| Unknown | 27 | 3.6 | 19 | 2.5 |

| Scope of LN dissectiona | ||||

| D1 | 5 | 0.7 | 6 | 0.8 |

| D2 | 143 | 18.9 | 153 | 20.1 |

| D3 | 610 | 80.5 | 601 | 79.1 |

| No. of LN examined | ||||

| Median [range] | 18.0 [1–78] | 16.0 [1–78] | ||

| ≥12 | 576 | 76.0 | 548 | 72.1 |

| Depth of tumor invasion (TNM 7th) | ||||

| T1 | 41 | 5.4 | 47 | 6.2 |

| T2 | 76 | 10.0 | 77 | 10.1 |

| T3 | 429 | 56.6 | 433 | 57.0 |

| T4a | 184 | 24.3 | 169 | 22.2 |

| T4b | 28 | 3.7 | 34 | 4.5 |

| Histologya | ||||

| Papillary | 14 | 1.8 | 22 | 2.9 |

| Tubular | 693 | 91.4 | 685 | 90.1 |

| Poorly, mucinous, signet | 51 | 6.7 | 53 | 7.0 |

| Lymphatic invasion | ||||

| Negative | 131 | 17.3 | 146 | 19.2 |

| Positive | 627 | 82.7 | 613 | 80.7 |

| Unknown | – | – | 1 | 0.1 |

| Venous invasion | ||||

| Negative | 254 | 33.5 | 241 | 31.7 |

| Positive | 504 | 66.5 | 518 | 68.2 |

| Unknown | – | – | 1 | 0.1 |

| No. of LN metastasis | ||||

| Median [range] | 2.0 [1–26] | 2.0 [1–25] | ||

| LN metastasis (TNM 7th) | ||||

| N1a | 331 | 43.7 | 331 | 43.6 |

| N1b | 266 | 35.1 | 265 | 34.9 |

| N2a | 116 | 15.3 | 115 | 15.1 |

| N2b | 45 | 5.9 | 49 | 6.4 |

| Stage (TNM 7th) | ||||

| IIIA | 106 | 14.0 | 119 | 15.7 |

| IIIB | 551 | 72.7 | 525 | 69.1 |

| IIIC | 101 | 13.3 | 116 | 15.3 |

Right-sided colon includes cecum, ascending, and transverse colon. Left-sided colon includes descending and sigmoid colon.

aJapanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma, Second English Edition [15].

PS, performance status; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; BMI, Body mass index; CEA, carcinoembrionic antigen; LN, lymph node.

disease-free survival

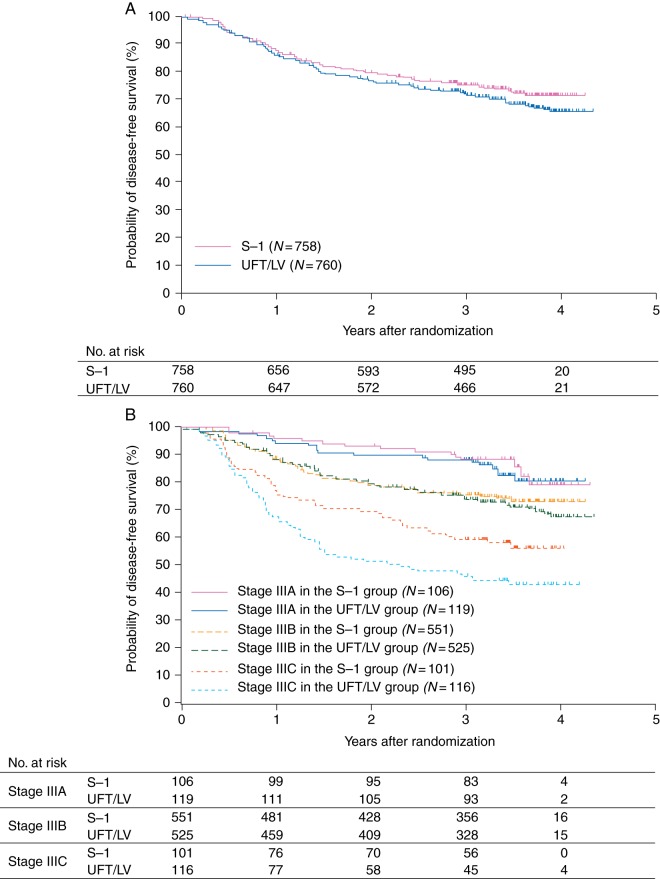

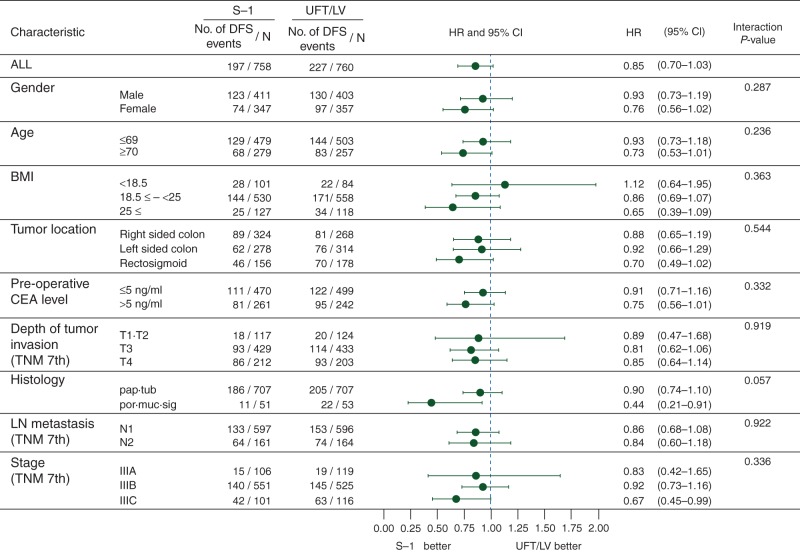

At the time of the analysis [median follow-up, 41.3 months; interquartile range (IQR), 37.9–45.0], 197 (26.0%) patients in the S-1 group and 227 (30.0%) in the UFT/LV group had DFS events; The DFS rate at 3 years was 75.5% (95% CI 72.2–78.4) in the S-1 group and 72.5% (95% CI 69.1–75.5) in the UFT/LV group (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The DFS curves for both groups are shown in Figure 2A. The P value for a noninferiority log-rank test with stratification was <0.001, demonstrating the noninferiority of the S-1 group to the UFT/LV group. The stratified HR for DFS was 0.85 (95% CI 0.70–1.03), which was similar even after excluding patients without the allocated treatment (N = 1504). And the HR adjusted by key baseline factors shown in Figure 3 was 0.87 (95% CI 0.71–1.06). DFS curves were clearly separated by TNM-stage subgroup (Figure 2B). In the subgroup analysis, no significant interactions were identified between the major baseline characteristics and the therapeutic effects of S-1 and UFT/LV; noninferiority of S-1 was not excluded in any subgroup defined on the basis of prognostic factors at baseline (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Disease-free survival. (A) Disease-free survival by treatment arm. Noninferiority stratified log-rank test, P < 0.001. The hazard ratio in the S-1 group compared with the UFT/LV group was 0.85 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.70–1.03]. The disease-free survival rate at 3 years was 75.5% (95% CI 72.2–78.4) in the S-1 group and 72.5% (95% CI 69.1–75.5) in the UFT/LV group. (B) Disease-free survival by UICC-TNM 7th stage. Disease-free survival rates at 3 years in stage IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC patients were 88.3%, 75.9%, and 60.1%, respectively, in the S-1 group, and 87.9%, 74.2%, and 46.4%, respectively, in the UFT/LV group.

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis of disease-free survival in the S-1 group compared with the UFT/LV group. DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; pap, papillary adenocarcinoma; tub, tubular adenocarcinoma; por, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma; muc, mucinous adenocarcinoma; sig, signet-ring cell carcinoma.

overall survival

At the time of the cutoff date for the primary analysis, 67 (8.8%) patients in the S-1 group and 77 (10.1%) in the UFT/LV group had died; the OS rate at 3 years was 93.6% (95% CI 91.5–95.1) in the S-1 group and 92.7% (95% CI 90.6–94.4) in the UFT/LV group.

safety

Details of the safety analysis have been previously reported [10]. In brief, stomatitis, anorexia, hyperpigmentation, and hematologic toxicities were common in S-1, while increased ALT and AST were common in UFT/LV. Except for diarrhea in the UFT/LV group (incidence, 5.5%), grade 3 or 4 toxicities occurred in <5% of both groups (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The protocol treatment completion rate in the S-1 and UFT/LV group was 76.5% and 73.4%, respectively, with no significant difference (P = 0.171). The mean of the relative dose intensity, including discontinuation cases, was 76.5% and 76.0% in the S-1 and UFT/LV group, respectively; the median was 95% in both groups.

discussion

This study, for the first time, demonstrated the efficacy of S-1 as adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer by confirming its noninferiority to UFT/LV in terms of DFS. As we previously reported [10], though the profile of toxicities differed, no significant difference was observed in terms of safety and feasibility between S-1 and UFT/LV.

Additionally, S-1 has several potential advantages over UFT/LV. First, the drug cost in Japan for 6 months of S-1 treatment is half that of UFT/LV treatment. Given its noninferiority in DFS, S-1 could be a welcome development from the both patients' and payers' perspective. An associated cost-effectiveness analysis is being conducted.

Second, S-1 may be more convenient to administer than UFT/LV. Although no definite difference in treatment compliance between the groups was observed over the relatively short treatment period (∼6 months) [10], many physicians think that patients regard the complex UFT/LV treatment schedule (every 8 h, avoiding 1 h before or after meals) as an obstacle, and the simpler S-1 treatment schedule (twice daily after meals) to be preferable.

Furthermore, when comparing S-1 with another oral fluoropyrimidine, capecitabine, the incidence of HFS must be taken into consideration. HFS is a common AE in capecitabine treatment, which often interferes with the patients' daily living; the X-ACT study showed that 60% patients treated with capecitabine experienced HFS, and 17% experienced ≥grade 3 [16]. In our study, S-1 rarely caused HFS (incidence, 1.3%) [10]; this can be a notable advantage of S-1 over capecitabine. A phase III study comparing S-1 and capecitabine as adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer is currently in progress in Japan (UMIN-CTR: UMIN000003272).

Personalization of adjuvant chemotherapy is an important issue to be resolved. We have focused on the differences in the mechanism of action between S-1 and UFT/LV or capecitabine, and associated translational researches investigating the tumor mRNA expressions and DNA copy numbers of 5-FU-related enzymes are being conducted.

On the basis of their reported superiority in DFS with a constant HR of 0.8 compared with 5-FU/LV [3, 4], oxaliplatin-containing regimens have been adopted as standard adjuvant chemotherapy in the United States and Europe since the mid-2000s. While oxaliplatin is an efficacious agent, its expected benefit may not be the same in all patients. de Gramont et al. indicated that stage III consists of subgroups of patients with various prognoses, and the expected benefits of oxaliplatin could vary according to stage subgroups [17].

The prognosis of stage IIIA patients in this study was favorable; their 3-year DFS rate was 88%, and it was similar to that (84.3%) of the stage II subgroup of the 5-FU/LV group in the MOSAIC study which did not recommend FOLFOX for stage II patients [18]. Similarly, when the HR for DFS with adding oxaliplatin is estimated to be 0.8 as reported [3, 4], the expected gain in 3-year DFS rate by adding oxaliplatin in these patients would be as small as 2%–3%. On the other hand, in the MOSAIC study, 15% patients received FOLFOX experienced some form of peripheral sensory neuropathy even at 4 years later [3]. Considering the expected benefits and the possible risks of increased toxicity and medical costs, oral fluoropyrimidine alone can be a considerable option for stage IIIA patients. In contrast, the prognosis of stage IIIC patients is poor. Oxaliplatin can be required for these ‘high-risk stage III’ patients.

Increasing numbers of elderly cancer patients is a common tendency among the developed nations. Patients aged ≥70 occupy 35% of our study population and 60% of colon cancer patients in the Japanese nationwide cancer registry [19]. Recent subgroup analysis showed marginal survival benefit from oxaliplatin as adjuvant treatment of patients aged ≥70, whereas oral fluoropyrimidines retained their efficacy [18, 20]. Therefore, oral fluoropyrimidines may play an important role in adjuvant chemotherapy for elderly patients. Age subgroup analyses are currently in progress.

In conclusion, adjuvant chemotherapy using S-1 for stage III colon cancer was demonstrated to be noninferior in DFS compared with UFT/LV. This study has presented S-1 as a new adjuvant treatment option that offers a lower drug cost and more convenient administration than UFT/LV and a lower incidence of HFS than capecitabine.

funding

This work was supported by the Foundation for Biomedical Research and Innovation, Translational Research Informatics Center, under the funding contract with Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Japan.

disclosure

MY has received honoraria from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Serono Co. Ltd, Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd; research funding from Taiho, Takeda, Chugai, Bristol-Myers, Daiichi Sankyo Co. Ltd, Sanofi K.K., Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co. Ltd, Nippon Kayaku Co. Ltd, Ono Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, and Jansen Pharmaceutical K.K. MI has received consulting fees from Taiho; honoraria from Taiho, Chugai, and Yakult Honsha Co. Ltd. KI has received research funding from Taiho. AT has received honoraria from Taiho. HM has received consulting fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Factory, Inc., and Sysmex Co.; honoraria from Taiho, Otsuka, Chugai, Yakult Honsha, Daiichi Sankyo, and Astellas Pharma, Inc.; research funding from Taiho, Otsuka, Takeda, and Pfizer Co. Ltd. KK has received consulting fees from Taiho and Chugai; honoraria from Taiho, Otsuka, Chugai, Takeda, Bristol-Myers, and Merck Serono. SK has received honoraria from Taiho, and Takeda; research funding from Taiho, Takeda, and Pfizer. KT has received honoraria from Taiho, Takeda, and Chugai. TW has received honoraria and research funding from Taiho, Takeda, Chugai, Daiichi Sankyo, Yakult Honsha, Bristol-Myers, and Merck Serono. MW has received consulting fees from Taiho, Chugai, Yakult Honsha, Johnson and Johnson KK and Covidien Japan Co. Ltd. NB has received honoraria from Taiho, Takeda, Daiichi Sankyo, Yakult Honsha, and Ono; research funding from Taiho. NT has received honoraria from Taiho, Takeda, Chugai, and Merck Serono; research funding from Taiho, Chugai, and Yakult Honsha. KS has received consulting fees from Taiho, Chugai, Bayer Yakuhin, Bristol-Myers, and Merck Serono; honoraria from Taiho, Takeda, Chugai, Yakult Honsha, Bristol-Myers, Merck Serono, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin; research funding from Taiho, Otsuka, Takeda, Chugai, Yakult Honsha, Daiichi Sankyo, Bristol-Myers, Merck Serono, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Ono, Tsumura & Co., Eisai Co. Ltd, Torii Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, and Kaken Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We are grateful to all patients and co-investigators for their cooperation for the ACTS-CC trial (Adjuvant Chemotherapy Trial of TS-1® for Colon Cancer). A list of participating institutions is given in the supplementary Appendix, available at Annals of Oncology online. The authors also thank the following additional investigators for their contributions to this trial: Yasuyo Kusunoki, Fumie Kinoshita, Hideki Kono, and Naoko Kashiwagi for data management; Akinori Ogasawara and Yuri Ueda as the project office staff; Hiroyuki Uetake, Toshiaki Ishikawa, Yoko Takagi, Aiko Saito, Sachiko Kishiro, and Yasuyo Okamoto as the translational study office staff; and Masanori Fukushima as a director of the Translational Research Informatics Center. The authors dedicate this article to the memory of Prof. Hiroya Takiuchi, who contributed to the conception and design of this study.

references

- 1.Labianca R, Nordlinger B, Beretta GD, et al. Early colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(suppl 6):vi64–vi72. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2014. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology; Colon cancer version 3 http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf. (9 June 2014, date last accessed)

- 3.André T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3109–3116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haller DG, Tabernero J, Maroun J, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil and folnic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1465–1471. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.6297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lembersky BC, Wieand HS, Petrelli NJ, et al. Oral uracil and tegafur plus leucovorin compared with intravenous fluorouracil and leucovorin in stage II and III carcinoma of the colon: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol C-06. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2059–2064. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimada Y, Hamaguchi T, Mizusawa J, et al. Randomised phase III trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with oral uracil and tegafur plus leucovorin versus intravenous fluorouracil and levofolinate in patients with stage III colorectal cancer who have undergone Japanese D2/D3 lymph node dissection: final results of JCOG0205. Eur J Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.05.025. June 20 [epub ahead of print], doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2014.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satoh T, Sakata Y. S-1 for the treatment of gastrointestinal cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13:1943–1959. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.709234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamada Y, Takahari D, Matsumoto H, et al. Leucovorin, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin plus bevacizumab versus S-1 and oxaliplatin plus bevacizmab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (SOFT): an open-label, non-inferiority, randomized phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1278–1286. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70490-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uesaka K, Fukutomi A, Boku N, et al. Randomized phase III trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine versus S-1 for patients with resected pancreatic cancer (JASPAC-01 study) J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4s. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hym178. abstr 145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mochizuki I, Takiuchi H, Ikejiri K, et al. Safety of UFT/LV and S-1 as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer in phase III trial: ACTS-CC trial. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1268–1273. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamaguchi T, Shirao K, Moriya Y, et al. Final results of randomized trials by the National Surgical Adjuvant Study of Colorectal Cancer (NSAS-CC) Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67:587–596. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe T, Itabashi M, Shimada Y, et al. Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR) guidelines 2010 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2012;17:1–29. doi: 10.1007/s10147-011-0315-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoenfeld DA, Richter JR. Nomograms for calculating the number of patients needed for a clinical trial with survival as an endpoint. Biometrics. 1982;38:163–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice RL. The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. New York: John Wiley & Sons,; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum. Japanese Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma-Second English Edition. Tokyo: Kanehara & Co., Ltd.,; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Twelves C, Wong A, Nowacki MP, et al. Capecitabine as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer. N Eng J Med. 2005;352:2696–2704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Gramont A, Chibaudel B, Bachet JB, et al. From chemotherapy to targeted therapy in adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer. Semin Oncol. 2011;38:521–532. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tournigand C, André T, Bonnetain F, et al. Adjuvant therapy with fluorouracil and oxaliplatin in stage II and elderly patients (between ages 70 and 75 years) with colon cancer: subgroup analyses of the Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin, Fluorouracil, and Leucovorin in the Adjuvant Treatment of Colon Cancer Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3353–3360. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.5645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research. Cancer statistics in Japan 2013 http://ganjoho.jp/pro/statistics/en/backnumber/2013_en.html. (9 June 2014, date last accessed)

- 20.McCleary NJ, Meyerhardt JA, Green E, et al. Impact of age on the efficacy of newer adjuvant therapies in patients with stage II/III colon cancer: findings from the ACCENT database. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2600–2606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.6638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.