These findings may potentially influence future clinical practice, with encouraging long-term survival data and better safety of masitinib with respect to sunitinib indicating a positive benefit–risk ratio. Considered in the setting of effective subsequent therapies, data show that adding masitinib to the armaterium of drugs used to treat GIST generates a clinically relevant survival benefit.

Keywords: GIST, imatinib-resistant GIST, phase II study, tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Abstract

Background

Masitinib is a highly selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor with activity against the main oncogenic drivers of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST). Masitinib was evaluated in patients with advanced GIST after imatinib failure or intolerance.

Patients and methods

Prospective, multicenter, randomized, open-label trial. Patients with inoperable, advanced imatinib-resistant GIST were randomized (1 : 1) to receive masitinib (12 mg/kg/day) or sunitinib (50 mg/day 4-weeks-on/2-weeks-off) until progression, intolerance, or refusal. Primary efficacy analysis was noncomparative, testing whether masitinib attained a median progression-free survival (PFS) (blind centrally reviewed RECIST) threshold of >3 months according to the lower bound of the 90% unilateral confidence interval (CI). Secondary analyses on overall survival (OS) and PFS were comparative with results presented according to a two-sided 95% CI.

Results

Forty-four patients were randomized to receive masitinib (n = 23) or sunitinib (n = 21). Median follow-up was 14 months. Patients receiving masitinib experienced less toxicity than those receiving sunitinib, with significantly lower occurrence of severe adverse events (52% versus 91%, respectively, P = 0.008). Median PFS (central RECIST) for the noncomparative primary analysis in the masitinib treatment arm was 3.71 months (90% CI 3.65). Secondary analyses showed that median OS was significantly longer for patients receiving masitinib followed by post-progression addition of sunitinib when compared against patients treated directly with sunitinib in second-line [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.27, 95% CI 0.09–0.85, P = 0.016]. This improvement was sustainable as evidenced by 26-month follow-up OS data (HR = 0.40, 95% CI 0.16–0.96, P = 0.033); an additional 12.4 months survival advantage being reported for the masitinib treatment arm. Risk of progression while under treatment with masitinib was in the same range as for sunitinib (HR = 1.1, 95% CI 0.6–2.2, P = 0.833).

Conclusions

Primary efficacy analysis ensured the masitinib treatment arm could satisfy a prespecified PFS threshold. Secondary efficacy analysis showed that masitinib followed by the standard of care generated a statistically significant survival benefit over standard of care. Encouraging median OS and safety data from this well-controlled and appropriately designed randomized trial indicate a positive benefit–risk ratio. Further development of masitinib in imatinib-resistant/intolerant patients with advanced GIST is warranted.

introduction

The first-line treatment of patients with KIT-positive, unresectable, recurrent, and/or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) imatinib; however, half of the patients will have experienced disease progression after ∼20 months [1]. Imatinib-resistant GIST patients show clear signs or symptoms of disease progression at the recommended starting dose of 400 mg/day [2]. Upon disease progression, physicians may choose to either escalate imatinib up to 800 mg/day or commence second-line treatment. The standard second-line treatment is sunitinib, although its benefit over placebo for overall survival (OS) is relatively short and there are numerous potentially serious side-effects [3–6]. Considering this unsatisfactory situation, we evaluated masitinib's potential to improve patient outcome with good tolerability in GIST patients after failure under imatinib.

Masitinib is a highly selective oral TKI with comparable activity to imatinib against wild-type and mutant KIT (exons 9 and 11) [7–9]. Given that the main kinase targets of masitinib are shared with imatinib and sunitinib, its higher kinase selectivity may translate into fewer off-target toxicities. Masitinib's activity in imatinib-naïve GIST has previously been reported as sustainable and well tolerated [10]. There is also evidence of masitinib activity in imatinib-resistant GIST as reported by a phase I study in solid tumors, which established an optimal dosage of 12 mg/kg/day in this population [11]. Post hoc analyses from that study also revealed masitinib (6.8–13 mg/kg/day) to generate an important effect on OS in imatinib-resistant GIST patients despite having only modest impact on progression-free survival (PFS) (see supplementary Section E, available at Annals of Oncology online).

methods

study design and procedures

This was a prospective, multicenter, randomized, open-label, two-parallel group, phase II study evaluating the safety and efficacy of masitinib (12 mg/kg/day administered orally in two daily intakes) for the treatment of advanced GIST in patients who showed disease progression while treated with imatinib (400–800 mg/day). In the event of severe toxicity related to masitinib, treatment interruption or dose reduction was permitted according to predefined criteria. Sunitinib (50 mg/day administered orally in a 4-weeks-on/2-weeks-off regimen) was used as an active control with toxicity related to sunitinib managed according to usual practice. Treatments were administered until progression, intolerance, or refusal, with disease progression assessed via CT scan at weeks 0, 4, 8, 16, 24, 36, and every 12 weeks thereafter.

Upon study termination, patients were allowed to switch from masitinib to sunitinib (50 mg/day in a 4-weeks-on/2-weeks-off regimen). In contrast, no cross-over from sunitinib to masitinib was allowed. This trial design, which is consistent with current guidelines on the conduct of randomized clinical trials in the setting of effective subsequent therapies, essentially tests whether administering the experimental treatment before the standard treatment is better than directly administering the standard treatment, while also complying with the ethical and pragmatic obligations that all patients should receive the standard of care following study withdrawal [12]. The investigation was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the national health authorities and a local central ethics committee.

patients and randomization

Patients showing disease progression while treated under imatinib ≥400 mg/day were eligible for inclusion. Other eligibility criteria included: aged 18 years or older; histological confirmation of metastatic or locally advanced nonoperable GIST; immunohistochemical detection of KIT (CD117) expression; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status ≤2; no prior TKI therapy other than imatinib, with the last imatinib administration being at least 4 days before randomization; and normal renal, cardiac, and hepatic functions. At baseline, patients were centrally randomized to treatments groups (1 : 1) using an Interactive Web Response System, with treatment allocated according to a modified minimization method. Stratification was done according to KIT mutation status; i.e. patients having a KIT exon 11 mutation versus patients with a KIT exon 9 mutation versus patients with any other mutation (or no available KIT result).

statistical analysis

With 19 patients per treatment arm, there was an 80% power of estimating median PFS to a precision of 2 months with alpha set to 10% one-sided. The study's primary analysis was noncomparative, testing whether masitinib could achieve a prospectively declared PFS threshold in line with that of sunitinib (albeit without demonstrating noninferiority in order to minimize patient recruitment in the context of an orphan disease). A statistical amendment was made to the prespecified threshold following commencement of the study but before database lock or efficacy analysis. This correction was unavoidable because the currently reported study population had a lower proportion of patients harboring the KIT exon 9 mutation with respect to the sunitinib historical study data used to generate statistical hypothesis; the latter of which was poorly matched to the general GIST population (see supplementary Section D, available at Annals of Oncology online). The primary analysis therefore tested whether the lower bound of the 90% unilateral confidence interval (CI) for median PFS (central RECIST) in the masitinib treatment arm was >3 months. PFS (central RECIST) was defined as the time from the date of randomization to the date of documented progression, calculated with RECIST from central blind reading (Dr Taieb, Centre Oscar Lambret, Lille, France), or any cause of death during the study. PFS for the primary analysis was evaluated using the Kaplan–Meier method with associated medians and 90% one-sided CI.

Secondary analyses on OS and PFS (central RECIST) were comparative, based on an alpha of 5% (two-sided), with results presented according to a two-sided 95% CI. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was developed to evaluate hazard ratios (HR). Both univariate and multivariate analyses of treatment effect on OS were carried out, with all data reported hereafter relating to the univariate model stratified on KIT status unless otherwise stated. Safety was assessed throughout the study by physical examination, vital signs, clinical laboratory evaluation, and monitoring of adverse events (AE) (NCICTCv4.2). Quality of life (QoL) was assessed using the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire with an improvement or worsening in QoL defined, respectively, as a change at any time-point of ±10 points from baseline. Longitudinally QoL assessment was carried out based upon time until definite deterioration analysis.

results

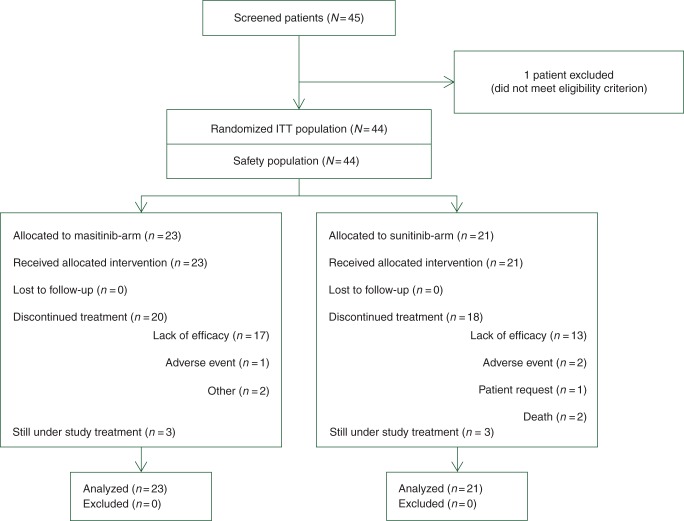

Between February 2009 and September 2011, 44 patients enrolled from nine study centers across France were randomly assigned to receive masitinib (23 patients) or sunitinib (21 patients). Patient baseline characteristics were well balanced between treatment arms, including duration of prior imatinib exposure, maximal imatinib dose received, KIT mutational status, and QoL (Table 1). There was no bias in baseline characteristics between treatment arms as evidenced by the reported nonsignificant difference. At the main cutoff date (31 January 2012; median follow-up of 14 months), 38 of 44 patients (86%) had withdrawn from the study (lack of efficacy being the main reason for termination in both treatment arms) and 6 of 44 patients (14%) were still ongoing, three from each treatment arm (Figure 1). Median exposure was 4.7 months for the masitinib treatment arm and 3.8 months (or 2.8 cycles) for the sunitinib arm. Patient compliance according to mean dose intensity was 90 ± 15% and 88 ± 14%, respectively. All results reported hereafter relate to final and validated data at a cutoff date of 31 January 2012, with exception of an additional follow-up analysis on OS that has a cutoff of 31 December 2012.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics (ITT population)

| Characteristic | Masitinib (n = 23) | Sunitinib (n = 21) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Gender (female) | 12 (52%) | 10 (48%) | 1.000 |

| Age (years) | 62 (31–82) | 67 (41–85) | 0.424 |

| ECOG PS: [0] | 14 (61%) | 12 (57%) | 1.000 |

| QLQ-C30 Global; mean (SD) | 65 (21) | 60 (20) | 0.486 |

| Disease characteristics | |||

| Years since diagnosis | 4.9 (1.2–11.7) | 4.9 (0.2–12.6) | 0.605 |

| Primary tumor localization | |||

| Small bowel | 11 (48%) | 11 (52%) | 0.582 |

| Gastroesophageal | 8 (35%) | 6 (27%) | |

| Other | 4 (17%) | 4 (19%) | |

| Tumor classification confirmed | |||

| Locally advanced | 2 (9%) | 3 (14%) | 0.658 |

| Metastatic | 21 (91%) | 18 (86%) | |

| Metastases tumor localization | |||

| Liver | 18 (78%) | 13 (62%) | 0.481 |

| Peritoneum | 6 (26%) | 8 (38%) | |

| Lung | 2 (9%) | 1 (5%) | |

| Pelvis (nonbone) | 0 (0%) | 2 (10%) | |

| Otherb | 11 (48%) | 9 (43%) | |

| KIT exon mutation | |||

| Not done | 4 (17%) | 4 (17%) | 1.000 |

| Exon 11 | 15 (79%) | 14 (82%) | |

| Exon 9 | 3 (16%) | 2 (12%) | |

| Exon 13 | 0 | 1 (6%) | |

| None (wild-type) | 1 (5%) | 0 | |

| Ratio exon 11 : 9 | 5 : 1 | 7 : 1 | |

| Maximal prior imatinib dose | |||

| 400 mg | 16 (70%) | 17 (81%) | 0.494 |

| 800 mg | 7 (30%) | 4 (19%) | |

| Cumulative prior exposure (months); median (range) | 33 (9–103) | 28 (5–114) | 0.707 |

Unless stated otherwise, data are mean (range) or number (%).

aFisher's exact test was used for comparison of qualitative variables, Wilcoxon test used for comparison of quantitative variables.

bOther = single occurrence per location. Location of ‘other’ metastases tumor for masitinib treatment arm: mediastinum, stomach, kidney, pancreas, bone, lymph nodes, pelvis abdominal, mesenteric mass, right iliac lesion, pelvic, right iliac, left hypochondrium, and mesentery. Location of ‘other’ metastases tumor for sunitinib treatment arm: colon/large intestine, pleura, soft tissue, rectum, mediastinum, stomach, interportal cava, surrenal mass, diaphragm, posterior thoracic, thoracic, retroperitoneal mass.

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; SD, standard deviation; QLQ-C30 Global, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) quality of life questionnaire core 30 item global health status.

Figure 1.

Trial profile (cutoff date: 31 January 2012).

A summary of safety is presented in Table 2. The masitinib treatment arm reported significantly fewer severe AEs compared with the sunitinib arm (52% versus 91%, respectively); fewer nonhematological grade 3 and any grade 4-related AEs (48% versus 76%); fewer nonfatal serious AEs (13% versus 33%); and fewer AEs leading to dose reduction (22% versus 38%). AEs reported at a significantly higher frequency in the sunitinib treatment arm were dysgeusia, hypertension, thrombocytopenia, mucosal inflammation, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome, and abdominal pain. Conversely, only nausea/vomiting was reported at a significantly higher frequency in the masitinib treatment arm.

Table 2.

Safety (ITT population) according to the number of patients with at least one reported adverse reaction; cutoff date: 31 January 2012.

| Number of patients (%) | Masitinib (n = 23) | Sunitinib (n = 21) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summary of AE | |||

| All AE | 22 (96%) | 21 (100%) | 1.000 |

| Severe AE | 12 (52%) | 19 (91%) | 0.008 |

| Nonfatal serious AE | 3 (13%) | 7 (33%) | 0.155 |

| Death under study treatment (plus 28 days) | 0 (0%) | 3 (14%) | 0.100 |

| Nonhaematological G3/4 | 11 (48%) | 16 (76%) | 0.069 |

| Any G4 AE | 1 (4%) | 2 (10%) | 1.000 |

| AE leading to: | |||

| Permanent discontinuation | 1 (4%) | 5 (24%) | 0.088 |

| Temporary interruption | 9 (39%) | 9 (43%) | 1.000 |

| Dose reduction | 5 (22%) | 8 (38%) | 0.325 |

| AEs of interestb | |||

| Nausea/vomiting | 16 (70%) | 7 (33%) | 0.033 |

| Diarrhea | 12 (52%) | 12 (57%) | 0.771 |

| Edema | 11 (48%) | 9 (43%)c | 0.771 |

| Rash/pruritus | 13 (57%)c | 12 (57%) | 1.000 |

| Neutropenia | 2 (9%) | 6 (29%) | 0.126 |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (4%) | 7 (33%) | 0.019 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 (0%) | 7 (33%) | 0.003 |

| Hypertension | 1 (4%) | 7 (33%) | 0.019 |

| Mucosal inflammation | 1 (4%) | 6 (29%) | 0.042 |

| Dysgeusia | 1 (4%) | 6 (29%) | 0.042 |

| Palmar-plantar ES | 1 (4%) | 6 (29%) | 0.042 |

| Other common AEs (≥15%) | |||

| Asthenia | 10 (44%) | 14 (67%) | 0.143 |

| Edema peripheral | 6 (26%) | 7 (33%) | 0.744 |

| Anemia | 12 (52%) | 6 (29%) | 0.136 |

| Neutropenia | 2 (9%) | 6 (29%) | 0.126 |

| Lymphopenia | 3 (13%) | 5 (24%) | 0.448 |

| Leukopenia | 2 (9%) | 5 (24%) | 0.232 |

| Headache | 1 (4%) | 5 (24%) | 0.088 |

| Anorexia | 5 (22%) | 5 (24%) | 1.000 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 4 (17%) | 4 (19%) | 1.000 |

| BPD | 7 (30%) | 2 (10%) | 0.137 |

| Eyelid edema | 6 (26%) | 2 (10%) | 0.245 |

aFisher's exact test.

bAdverse events commonly associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors or reported with a significantly higher frequency in one treatment arm.

cIncluding one G3 AE (edema or pruritus as applicable).

AE, adverse event; G3, grade 3 AE; G4, grade 4 AE; Palmar-plantar ES, Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome; BPD, Blood phosphorus decreased.

At baseline, patient QoL according to QLQ-C30 was globally good and similar between treatment arms. For those patients with QoL response data available, an improved or stable QoL was reported more frequently in patients from the masitinib treatment arm; specifically, 10 of 15 patients (67%) versus 5 of 13 patients (39%) from the masitinib and sunitinib treatment arms, respectively. Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that median time to definite deterioration was 6.2 months (95% CI 3.8–NR) in patients from the masitinib treatment arm and 3.8 months (95% CI 2.1–9.3) in patients from the sunitinib treatment arm. Hence, masitinib tended to less severely affect the QoL of patients than sunitinib.

The primary efficacy analysis met its stated statistical objective: the lower bound of the 90% unilateral CI for median PFS (central RECIST) was greater than the threshold of 3 months. Specifically, median PFS (central RECIST) for the primary noncomparative analysis in the masitinib treatment arm was 3.71 months (90% CI 3.65). This successful result was repeated for sensitivity analyses, including local RECIST PFS, investigator-based PFS, time-to-treatment failure, time-to-treatment switch, and different censoring methods (see supplementary Section A, available at Annals of Oncology online). According to study design, comparative secondary efficacy analyses on OS and PFS (central RECIST) were to be carried out upon success of the noncomparative primary analysis.

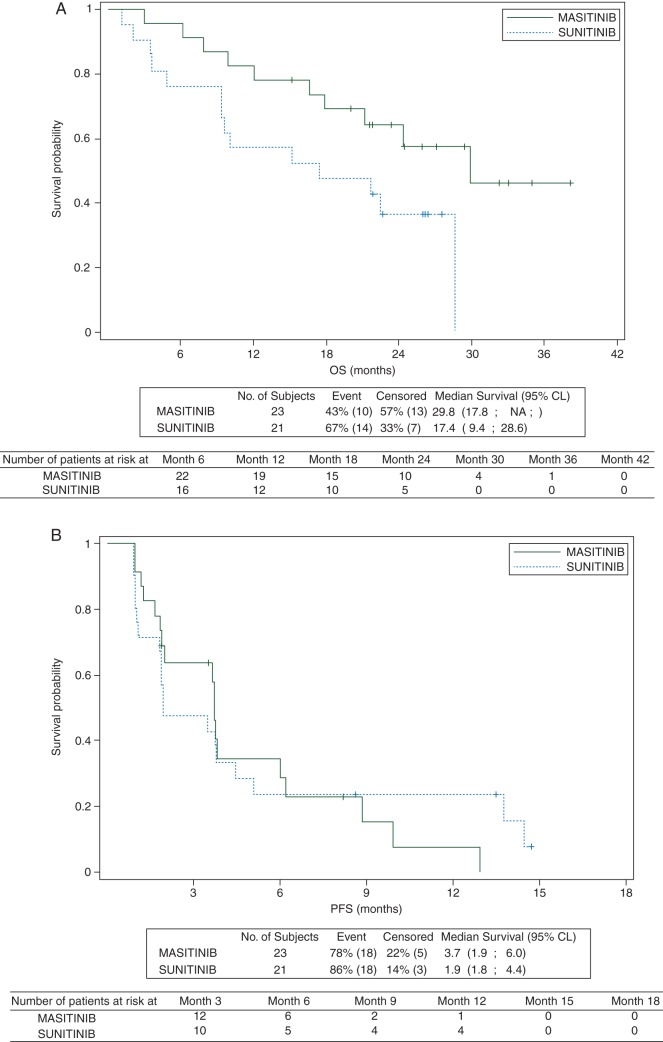

In the overall population, OS was significantly increased in the masitinib treatment arm with a median OS ‘not reached’ but estimated to be >21.2 months (95% CI 21.2–NR) compared against 15.2 months (95% CI 9.4–21.7) in the sunitinib arm (P = 0.016). This corresponded to a HR of 0.27 (95% CI 0.09–0.85). Potential bias in baseline characteristics was explored via multivariate analysis, the resultant multivariate Cox model confirming the observed treatment effect with a HR of 0.27 (95% CI 0.09–0.78). A follow-up analysis on OS (cutoff 31 December 2012) was carried out to test whether the observed treatment effect on OS was sustained. At a median follow-up of 26 months, 40 of 44 patients (91%) had withdrawn from the study and 4 of 44 patients (9%) were still ongoing (one in the masitinib treatment arm and three in the sunitinib arm). Median OS in the overall population was 29.8 months (95% CI 17.8–NR) for the masitinib treatment arm compared with 17.4 months (95% CI 9.4–28.6) for the sunitinib arm (P = 0.033). This corresponds to a HR of 0.40 (95% CI 0.16–0.96) (Figure 2A). Median PFS (central RECIST) for the secondary comparative analysis, i.e. according to a two-sided 95% CI, was in the same range for the masitinib and sunitinib treatment arms, respectively, 3.7 months (95% CI 1.9–6.0) versus 1.9 months (95% CI 1.8–4.4) (Figure 2B). The corresponding HR was 1.1 (95% CI 0.6–2.2, P = 0.833).

Figure 2.

(A) Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival (secondary efficacy analysis) in imatinib-resistant GIST patients (univariate model; intention-to-treat analysis). Cutoff date: 31 December 2012 with corresponding median follow-up of 26 months. Overall survival was defined as the time from randomization to the date of documented death. If death was not observed at the time of analysis data was to be censored at the last date the patient was known to be alive. (B) Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression-free survival (secondary efficacy analysis) assessed according to central RECIST stratified on KIT exons in imatinib-resistant GIST patients (univariate model; intention-to-treat analysis). Cutoff date: 31 January 2012 with corresponding median follow-up of 14 months.

The number of poststudy treatments received was similar between treatment arms, as were the types of therapy administered with an obvious exception for sunitinib due to the one-way cross-over design (see supplementary section B, available at Annals of Oncology online). Of those patients terminating study treatment, 19 of 20 (95%) from the masitinib treatment arm received at least one poststudy treatment as opposed to 13 of 18 (72%) from the sunitinib arm, with death or poor health condition precluding any option for poststudy treatment in the remaining patients. Analysis of death in patients who did not receive a poststudy treatment showed that in the sunitinib treatment arm: two patients died while under study treatment, one for unknown reason and one unrelated to treatment; one patient died 10 days after study termination due to disease progression; and two patients died 1.6 months after study termination due to pulmonary embolism for one, and progressive disease for the other (see supplementary Section C, available at Annals of Oncology online). In comparison, one patient died from disease progression 4.7 months after study termination in the masitinib treatment arm.

discussion

This study met its primary analysis end point, namely, that the lower bound of the 90% unilateral CI for median PFS (central RECIST) was above a threshold of 3 months for the masitinib treatment arm. As a secondary analysis, masitinib followed by the standard of care showed a statistically significant survival benefit [HR = 0.27 (0.09–0.85)], despite the risk of progression while under treatment with masitinib being in the same range as for sunitinib [HR = 1.1 (0.6–2.2)]. Additionally, the safety profile of masitinib was better than that of sunitinib, as evidenced by masitinib-treated patients experiencing less toxicity and reporting a longer time until definite QoL deterioration.

The better safety profile of masitinib when compared against sunitinib can be considered as clinically relevant because transition from imatinib to sunitinib can present a challenge for many patients. For example fatigue, possibly related to sunitinib-induced hypothyroidism, is a common side-effect reported in 74% of all patients that can produce highly negative, possibly dose limiting, effects on QoL [6, 13]. Consequently, the use of dose reduction or temporary dose interruption is often necessary to manage sunitinib's side-effects, the incidence of which tends to increase slightly over time [5, 14]. Hence, there remains an unmet medical need in terms of safety that is addressed with masitinib.

A finding also considered as clinically relevant was that patients from the masitinib treatment arm reported a significant survival advantage of 12.4 months relative to the sunitinib treatment arm (i.e. median OS of 29.8 versus 17.4 months, respectively) after a follow-up of 26 months. This observed survival benefit for the masitinib treatment arm appears robust as evidenced from a sustained significant difference in median OS between treatment arms at time-points separated by 12 months (i.e. median follow-up times of 14 and 26 months). The observed masitinib treatment-arm median OS also compares positively against historical sunitinib data, which are commonly reported at ∼17 months (see also supplementary Section D, available at Annals of Oncology online); moreover, this comparison indicates that the current study's sunitinib treatment arm is well-representative of sunitinib in second-line treatment [3, 5, 14].

Although it was predefined that comparative secondary efficacy analyses on OS and PFS (central RECIST) were to be carried out upon success of the noncomparative primary analysis, no order for sequencing secondary analyses was specified. Unless otherwise stated, OS is generally considered as the variable of highest rank because this represents the gold standard in oncology and is an investigator-independent assessment of disease outcome. However, this situation raises possible multiplicity issues, i.e. if both OS and PFS were to be tested in parallel, hence family-wise error rate adjustment to protect against type I error for multiple tests was carried out. Adjusting for multiplicity testing using Bonferroni methodology, which is the most conservative approach, the adjusted statistical significance corresponds to an alpha risk of 0.025. Considering the observed P value in OS analysis at the main cutoff date (31 January 2012) was P = 0.016, the treatment effect in OS still achieves statistical significance following adjustment for theoretical multiplicity.

An evaluation of known sources of bias was carried out to verify whether the observed treatment effect on OS was credible. Such analyses revealed no statistically significant difference between treatment arms for the following established prognostic factors: KIT mutational status, duration of prior imatinib exposure, maximal prior imatinib dose, tumor localization, prior treatments, ECOG status, and numerous other baseline characteristics (see Table 1 and also supplementary Section B, available at Annals of Oncology online). Additional proof of treatment-arm homogeneity was evident from the observation that univariate and multivariate analyses on OS produced very similar results. Consequently, no bias that would benefit the masitinib treatment arm was detected in the current dataset signifying that these data are robust.

A possible criticism of this study is that any comparative analysis on OS might be confounded by permitting patients to switch from masitinib to sunitinib following study termination; however, this stand point is unfounded based on both ethical and pragmatic considerations. Indeed, the one-way cross-over design utilized in this study, and hence the absence of a double cross-over, is consistent with recommendations from published guidelines on the conduct of randomized clinical trials in the setting of effective subsequent therapies, and thus represents the most appropriate design to evaluate relevant clinical benefit of masitinib as a second-line treatment in GIST [12]. In such a clinical setting, the observed difference in OS between treatment arms is considered the relevant measure of clinical benefit, regardless of subsequent therapies, provided that the subsequent therapies used in both treatment arms followed the current standard of care. This exactly describes the current study's design, i.e. treatment of imatinib-resistant GIST with a regimen of masitinib followed by standard of care (sunitinib then other therapies) compared against the standard of care, indicating that the study findings have a methodologically sound basis. The salient point demonstrated by this study was that adding masitinib to the armaterium of drugs used to treat GIST generates a clinically relevant survival benefit, regardless of the complexities inherent to assigning a specific OS contribution to a drug in the setting of effective subsequent therapies.

External validation of the observed OS benefit for masitinib in imatinib-resistant GIST is evident in data from an independent dataset of the aforementioned phase I study [11]. Briefly, 12 imatinib-resistant GIST patients received masitinib doses ranging from 6.8 to 13 mg/kg/day with a median OS of 23.4 months (95% CI 12.4–34.4) (see supplementary Section E, available at Annals of Oncology online). This OS would undoubtedly be increased further if followed by a proven active treatment arm, such as sunitinib, which was not used for GIST at the time this phase I study was carried out. Thus, within the limitations of historical comparisons, the OS benefit reported in the current study is not without precedent.

To observe a median OS benefit in the absence of PFS gains is an unusual finding. However, it is not entirely unexpected that PFS for masitinib and sunitinib were in the same range considering that at therapeutic doses both TKIs inhibit c-Kit and PDGFRα by a similar magnitude [8]. Logically therefore, alternative mechanisms of action must be implicated. It has been suggested that innate immunity plays a role in GIST disease progression; the survival of GIST patients correlating positively with increased activity of natural killer cells [15, 16]. Consistent with this mechanism of action, it has been shown that masitinib is capable of inducing dendritic cell-mediated natural killer cell activation, probably via its highly selective inhibition of c-Kit (see supplementary Section F, available at Annals of Oncology online) [17]. Additionally, recent data suggest that masitinib may induce the recruitment of macrophages with a potential antitumoral activity within the tumor (Hermine O, 2013; personal communication). Together, these modifications of the tumor microenvironment may prevent dissemination, reducing aggressiveness of the tumor without direct inhibition of tumor growth. This may explain the observed effect of masitinib on long-term but not short-term survival.

In summary, this was a well-controlled and appropriately designed randomized clinical trial for comparing the efficacy and safety of masitinib followed by standard of care in imatinib-resistant GIST against the standard of care. Encouraging long-term median OS data for the masitinib treatment arm coupled with better safety of masitinib when compared against sunitinib indicate a positive benefit–risk ratio. An international phase III trial of masitinib in imatinib-resistant/intolerant patients with advanced GIST is in progress, the objectives of which are to reaffirm that masitinib has a superior safety profile to that of sunitinib in this population and also to confirm the observed survival benefits of administering masitinib in the second-line setting.

funding

This work was supported by AB Science, Paris, France (no grant number). The sponsor was involved in the study design; data handling (monitoring, collection, analysis, and interpretation); manuscript preparation and submission. The principal investigator and lead author had full access to all data. All authors approved the final manuscript.

disclosure

ALC has received honoraria from Pfizer, Novartis, Pharmamar, and GSK. AA has received honoraria from Pfizer, Novartis, and Bayer; and research funding from AB Science, Novartis, and Bayer. JYB has received honoraria from AB Science, Pfizer, Novartis, and Bayer. OB has received an honorarium from Pfizer. Masitinib is under clinical development by the study sponsor, AB Science (Paris, France). AM, CM, and YA are an employees and shareholders of the study sponsor. OH and PD are consultants and shareholders of the study sponsor. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We thank the patients who participated in this trial and their families, all the participating investigators and clinical staff, and also members of the Data Review and Central Review Committees. Lise Barbin provided medical writing services on behalf of AB Science. Taieb (Centre Oscar Lambret, Lille, France), an independent expert with no direct involvement in the conduct of the study, carried out the blinded central review of PFS for generation of the data referred to as ‘PFS (central RECIST)’. Taieb formally confirmed that, although affiliated to a hospital in which the study was being run, there are no hierarchical or financial links between the respective departments and that this statement was applicable to all concerned employees.

references

- 1.Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor Meta-Analysis Group GSTMA. Comparison of two doses of imatinib for the treatment of unresectable or metastatic gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a meta-analysis of 1,640 patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1247–1253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Novartis. Glivec: summary of product characteristics. URL: www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/gleevec_tabs.pdf. (14 May 2014, date last accessed)

- 3.Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joensuu H, Trent JC, Reichardt P. Practical management of tyrosine kinase inhibitor-associated side effects in GIST. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37:75–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demetri GD, Garrett CR, Schoffski P, et al. Complete longitudinal analyses of the randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial of sunitinib in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumor following imatinib failure. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3170–3179. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwandt A, Wood LS, Rini B, Dreicer R. Management of side effects associated with sunitinib therapy for patients with renal cell carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2009;2:51–61. doi: 10.2147/ott.s4052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubreuil P, Letard S, Ciufolini M, et al. Masitinib (AB1010), a potent and selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting KIT. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis MI, Hunt JP, Herrgard S, et al. Comprehensive analysis of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1046–1051. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anastassiadis T, Deacon SW, Devarajan K, et al. Comprehensive assay of kinase catalytic activity reveals features of kinase inhibitor selectivity. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1039–1045. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Cesne A, Blay JY, Bui BN, et al. Masitinib in imatinib-naive advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST): five-year follow-up of the French Sarcoma Group phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30 (suppl) abstr 10089. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soria JC, Massard C, Magne N, et al. Phase 1 dose-escalation study of oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor masitinib in advanced and/or metastatic solid cancers. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2333–2341. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korn EL, Freidlin B, Abrams JS. Overall survival as the outcome for randomized clinical trials with effective subsequent therapies. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2439–2442. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.6056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood LS. Managing the side effects of sorafenib and sunitinib. Commun Oncol. 2006;3:558–562. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seddon B, Reichardt P, Kang Y, et al. Detailed analysis of survival and safety with sunitinib in a worldwide treatment-use trial of patients with advanced imatinib-resistant/intolerant GIST; London, UK: Connective Tissue Oncology Society; 2008. Presented at the (Abstr 34980) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Menard C, Blay JY, Borg C, et al. Natural killer cell IFN-gamma levels predict long-term survival with imatinib mesylate therapy in gastrointestinal stromal tumor-bearing patients. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3563–3569. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borg C, Terme M, Taieb J, et al. Novel mode of action of c-kit tyrosine kinase inhibitors leading to NK cell-dependent antitumor effects. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:379–388. doi: 10.1172/JCI21102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Auclair C, Tursz T, Zitvogel L. Use of specific inhibitors of tyrosine kinases for immunomodulation. 2004 WO2004026311 A2 (Patent) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.