Abstract

Cancer is the leading cause of death among Asian Americans, but screening rates are significantly lower in Asians than in non-Hispanic Whites. This study examined associations between acculturation and three types of cancer screening (colorectal, cervical, and breast), focusing on the role of health insurance and having a regular physician. A cross-sectional study of 851 Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese Americans was conducted in Maryland. Acculturation was measured using an abridged version of the Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale (SL-ASIA), acculturation clusters, language preference, length of residency in the U.S., and age at arrival. Age, health insurance, regular physician, gender, ethnicity, income, marital status, and health status were adjusted in the multivariate analysis. Logistic regression analysis showed that various measures of acculturation were positively associated with the odds of having all cancer screenings. Those lived for more than 20 years in the U.S. were about 2-4 times [odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI): colorectal: 2.41 (1.52-3.82); cervical: 1.79 (1.07-3.01); and breast: 2.11 (1.25-3.57)] more likely than those who lived for less than 10 years to have had cancer screening. When health insurance and having a regular physician were adjusted, the associations between length of residency and colorectal cancer (OR: 1.72 (1.05-2.81)) was reduced and the association between length of residency and cervical and breast cancer became no longer significant. Findings from this study provide a robust and comprehensive picture of AA cancer screening behavior. They will provide helpful information on future target groups for promoting cancer screening.

Keywords: Asian Americans, Acculturation, Early Detection of Cancer, Breast Neoplasms/prevention & control, Uterine Cervical Neoplasms/prevention & control, Colorectal Neoplasms/prevention & control

Cancer is the leading cause of death among Asian Americans unlike in all other American racial and ethnic groups where the leading cause of death is heart disease [1]. The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends regular screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer in order to increase the chances of early detection [2]. Despite these recommendations, screening rates for colorectal, cervical, and breast cancer have been consistently and significantly lower in Asians than in non-Hispanic Whites [3]. According to data from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), only 46.9% Asian Americans received regular colorectal cancer screening, 75.4% received a Pap smear within the past three years, and 64.1% received a mammogram within the past two years, as compared to non-Hispanic Whites where 59.8%, 83.4%, and 72.8% received regular screening for each of these cancers respectively [3]. Low acculturation and limited access to health care, including having a usual source of care and health insurance, have been found to contribute to these low cancer screening rates in Asian Americans [4]. However, depending on the measure of acculturation and the specific cancer screening test being investigated, there have been varying results regarding whether there is a significant association with increased acculturation and cancer screening behavior among Asians [5-9].

Colorectal cancer screening

For cancer incidence and mortality among Asian and Pacific Islanders (APIs) in the U.S., colorectal cancer ranks in the top three for both men and women [10]. To detect colorectal cancer at an early stage when it is easiest to treat, screening tests are recommended to find precancerous polyps or abnormal growths in the colon or rectum which can then be removed [11]. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about half of the reduction in the expected number of new cases and deaths from colorectal cancer can be attributed to screening [11]. There have been mixed findings with regards to the association between acculturation and colorectal cancer screening [5, 12], In a study by Tang et al., greater acculturation, as measured by the Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation Scale (SL-ASIA), among Chinese-American women was found to be significantly associated with having had a Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT) at least once, and both greater acculturation and a physician’s recommendation were significant predictors of having had a sigmoidoscopy at least once [5]. However, in another study examining Latino and Vietnamese adults in California, acculturation, as measured using the Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics, was not found to be significantly associated with having had a FOBT in past year, sigmoidoscopy in the past 5 years, or colonoscopy in the past 10 years [12].

Cervical cancer screening

In the U.S., cervical cancer ranks eleventh for cancer incidence and mortality among API women [10]. Despite cervical cancer being identified by the CDC as the easiest female cancer to prevent with regular screening tests and follow-up, there has been an overall small, decreasing trend in the number of women who report having had a Pap test within the past 3 years [3, 13]. Previous studies have suggested that higher levels of acculturation are associated with receipt of cervical cancer screening [6-8, 14]. Among Asian women, those who lived 0 to 4 years in the U.S. were significantly less likely to have had cervical cancer screening (OR=0.47, 95% CI= 0.40, 0.54) as compared to women who were native born [14]. In another study examining Korean Americans, women who had good or little English proficiency had 2.91 times greater odds of having had a Pap smear than those with no English proficiency (95% CI=1.15-7.38) [8]. Similarly, Chinese American women with greater English proficiency (OR= 1.39, 95% CI= 1.13-1.72) were more likely to have received regular Pap smears [6]. Furthermore, a study examining Vietnamese women found that more acculturated women, as measured by SL-ASIA, were more likely to be sexually active and to obtain regular Pap smears (p<0.05) than less acculturated women [7].

Breast cancer screening

For API women in the U.S., breast cancer ranks first for cancer incidence and second for cancer mortality [10]. Moreover, breast cancer incidence rates have been increasing for Asian American women especially among the foreign-born, who normally have low rates of breast cancer in their native countries [15]. Screening for breast cancer is essential considering that evidence has shown that mammography in women aged 40 to 70 years decreases breast cancer mortality [16]. Inconsistent results have been found among previous studies in regards to the relationship between acculturation and breast cancer screening [8, 9, 17]. In a study specifically investigating Asian American women, living in the U.S. for 15 or more years (OR=1.65, 95% CI=1.29-2.12) and speaking English well (OR=1.67, 95% CI= 1.2-2.52) were positively associated with having breast cancer screening in the past 12 months [17]. On the contrary, proportion of life in the U.S., (comparing whether a woman had spent less than or equal to 25% or more than 25% of her life in the U.S.) and spoken English proficiency (comparing good/little and no proficiency) were not found to be significantly associated with having a mammogram in a study investigating Korean American women [8]. Another study investigating Vietnamese women found that English fluency was not significant but that the number of years in the U.S. (OR=1.06, 95%CI=1.01-1.11) was positively associated with having ever had a mammogram [9].

In the current study, we employed five different types of acculturation measures (SL-ASIA, clusters, language preference, length of residency, and age at arrival) to test associations with three different types of cancer screenings (colorectal, cervical, and breast) among three ethnic groups of Asian Americans (Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese Americans) to capture the complexity of acculturation process and understand a comprehensive picture of an association between acculturation and cancer screening among Asian Americans. We hypothesize that more acculturated Asian Americans are more likely to receive cancer screening.

Methods

Participants

Data from the current study was collected as part of the Asian Liver Cancer Education program, which was a randomized community trial on liver cancer prevention education among Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese Americans in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area. From November 2009 to June 2010, we recruited 877 participants through community-based or faith-based organizations (including churches, temples, and language schools) and through other channels such as Asian grocery markets/restaurants, nail salons, universities, and individual networks. Subjects were eligible to participate if they: (1) self-identified as Chinese/Korean/Vietnamese Americans; (2) were 18 years of age or over; and (3) had never participated in another hepatitis B or liver cancer education program. At the study sites, participants filled out questionnaires containing questions on demographics, health status, acculturation, health care accessibility and utilization including cancer screenings, and health behaviors. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and University of Maryland, College Park. For this particular study, the analytic sample excluded participants who had missing information on acculturation variables or cancer screening outcomes, which resulted in a total sample of 846.

Independent variable: Acculturation

In light of the multi-faceted nature of acculturation and the lack of a standard measure for use in the Asian American population, we used multiple measures of acculturation to compare and contrast their relationships with cancer screening behavior among Asian Americans. The principal measure used in the current study was the revised version of SL-ASIA, which consisted of 10 multiple choice questions measured on a 5-point Likert scale [18]. Items covering the following aspects were included in the scale: language (speak, read and preference), ethnic origin of friends and peers (before age six, between age six to 18, people associated with in the community), music preference, food choice (at home and in restaurants), and self-identity. The response categories for the multiple choice questions were exclusively Asian, somewhat Asian, equal, somewhat American, and exclusively American. Additionally, the SL-ASIA included four open questions on generation status (first versus others), years of education in the home country and U.S., as well as years of residence in the U.S. and the country of origin. We then calculated the percentage of years spent living in the U.S. and the percentage of years of education in the U.S. based on the above information. All scale items were standardized and then averaged to obtain a continuous summary score for each participant.

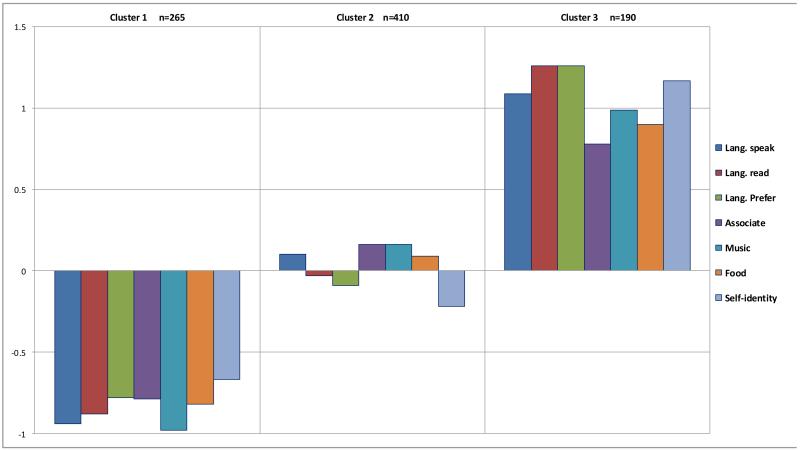

To improve the interpretation of the SL-ASIA, we conducted cluster analysis using seven key variables of SL-ASIA, namely language spoken, language read, language preference, people associated within the community, music preference, food preference in restaurants, and self-identity. Compared to the other scale items, these variables captured more variation in the acculturation status of our sample, which consisted mostly of first generation immigrants (97%). For example, the question on the ethnic origin of peers before age six had very few “Exclusively American” or “Mostly American” responses since the vast majority of participants lived in their home country at that time. Therefore, we excluded such questions to focus on the items that better reflected the composition of our sample. Using a person-oriented approach, those who had similar patterns of acculturation were grouped together. Clusters were created using a two-step approach. This method consists of creating ‘pre-clusters’ and then clustering the pre-clusters using hierarchical methods to identify the recommended number of clusters. Partitions were determined using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm for maximum likelihood, using initial values from agglomerative hierarchical clustering. Models were compared using an approximation to the Bayes factor based on Schwarz’s Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Unlike significance tests, this method allows for the comparison of more than two models at the same time and removes the restriction requiring models being compared to be nested [19]. The selection of a similarity measure and the determination of the number of clusters were based on the smallest change in BIC values [20]. In this manner, we found three clusters representing Asian, bicultural, and American cultural orientations. SPSS v19 (SPSS Inc.) was used to perform the cluster analysis.

To further examine the relationship between acculturation and cancer screening behaviors, we also used individual measures including age at arrival in the U.S., length of residency in the U.S., and language preference. Using the information gathered from the open question “years of living in the U.S.” and respondents’ current ages, we were able to derive the age at arrival (categorized as 0-20, 21-30, 31-40 and 41 years or above) and the length of residency in the U.S. (categorized as 0-10, 11-20 and 21 years or above). Language preference was measured by the question “What language do you prefer” on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from exclusively Asian to English only, which was collapsed into three categories for analysis purposes.

Dependent variable

Cancer screenings. Participants self-reported whether they had received a screening test for colorectal cancer (e.g., sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy), a Pap smear test (females only), or a mammogram (females only) in the last two years using binary responses (yes versus no).

Covariates

A number of variables were identified to be significantly associated with acculturation and cancer screening and were thus adjusted for in the multivariate-adjusted logistic regression. Covariates included age (continuous), gender, education, household income, having health insurance, having a regular physician, marital status, and ethnicity. Answers to having health insurance and a regular physician were coded as either yes or no. Marital status had three categories: married, unmarried (including living with a partner, separated, divorced, separated, remarried, and widowed), and never been married. To account for the missing responses to annual household income (n=30), a missing category was created in addition to the original five income levels (< $20,000, $20,000 to $49,999, $50,000 to $74,999, $75,000 to $100,000 and $100,000 or more). Education level was grouped into less than high school, high school, some college, and college graduates or higher.

Statistical analysis

To examine whether the sociodemographic characteristics differ by acculturation cluster in our study sample, we performed chi-square tests for the categorical covariates and ANOVA for the continuous covariates (age). We then performed bivariate analysis to assess the relationship between each covariate and cancer screening adjusting for age. To further examine the confounding effect of these covariates, we conducted step-wise logistic regression by adding covariates one by one into the age-adjusted models for each cancer screening outcome across all acculturation measures. Having health insurance and having a regular physician were almost always significantly associated with cancer screenings and had the largest impact on the estimates of the associations between acculturation variables and cancer screening outcomes. Other covariates behaved less consistently across all acculturation measures and had weaker confounding effects.

To illustrate how these factors affect the association between acculturation and different cancer screenings, a series of multiple logistic regressions were performed. The first and most basic model was age-adjusted only. Each consecutive model built upon the previous by adjusting for additional covariates. Model 2 adjusted for age and having health insurance, and Model 3 included having a regular physician in addition to the covariates adjusted for in Model 2. Model 4 adjusted for all other covariates.

Using Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) as an indicator for multicollinearity, education was found to have a high VIF (5.2) and was removed from the final models. Without education, all VIF values were found to be in an acceptable range (1.06 to 4.1 with most being less than 2.5). Interaction between acculturation variables and cancer screenings were tested, and stratified analysis was performed if the interaction was significant.

Results

In the present study, 22%, 63%, and 57% of participants received colorectal, cervical, and breast cancer screening in the past two years. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics by acculturation clusters among the 846 participants. Characteristics of participants differed significantly by acculturation status. Compared to those in the Asian cluster, those in the American cluster were more likely to be younger, male, Vietnamese, have a higher family income, be highly educated, and never married. The percentages of having health insurance, a regular physician, and good health status were also significantly higher in the American cluster. Therefore, we considered these variables as potential confounders in logistic regression models. For each of the outcomes, we conducted a series of multiple logistic regression models across the five acculturation measures adjusting for the confounders. The results for each outcome are presented in Tables 2-5.

Table 1. Participant sociodemographic characteristics by acculturation status, n=846.

| Total | Acculturation clusters | P-valuea | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=846 | Asian n=258 |

Bicultural n=401 |

American n=187 |

||||||

| Age (mean, SE) | 45.0 | 13.4 | 52.4 | 12.7 | 43.8 | 12.3 | 37.3 | 11.6 | <.0001 |

| Gender (n, %) | 0.0004 | ||||||||

| Male | 354 | 41.8 | 87 | 33.7 | 169 | 42.1 | 98 | 52.4 | |

| Female | 492 | 58.2 | 171 | 66.3 | 232 | 57.9 | 89 | 47.6 | |

| Ethnicity (n, %) | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Korean | 285 | 33.7 | 87 | 33.7 | 155 | 38.7 | 43 | 23.0 | |

| Chinese | 294 | 34.7 | 83 | 32.2 | 155 | 38.7 | 56 | 29.9 | |

| Vietnamese | 267 | 31.6 | 88 | 34.1 | 91 | 22.6 | 88 | 47.1 | |

| Education (n, %) | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 111 | 13.1 | 81 | 31.4 | 27 | 6.7 | 3 | 1.6 | |

| High school | 173 | 20.5 | 84 | 32.6 | 72 | 18.0 | 17 | 9.1 | |

| Some college | 107 | 12.6 | 20 | 7.7 | 48 | 12.0 | 39 | 20.9 | |

| College Graduates or higher | 455 | 53.8 | 73 | 28.3 | 254 | 63.3 | 128 | 68.4 | |

| Annual household income (n, %) | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Missing | 30 | 3.6 | 14 | 5.4 | 11 | 2.7 | 5 | 2.7 | |

| Less than $20,000 | 200 | 23.6 | 111 | 43.0 | 70 | 17.4 | 19 | 10.2 | |

| $20,000 to $49,999 | 254 | 30.0 | 85 | 32.9 | 131 | 32.7 | 38 | 20.3 | |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 110 | 13.0 | 19 | 7.4 | 52 | 13.0 | 39 | 20.8 | |

| $75,000 to $99, 000 | 96 | 11.4 | 18 | 7.0 | 50 | 12.5 | 28 | 15.0 | |

| $100,000 or more | 156 | 18.4 | 11 | 4.3 | 87 | 21.7 | 58 | 31.0 | |

| Marital status (n, %) | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Married | 647 | 76.5 | 215 | 83.3 | 321 | 80.0 | 111 | 59.3 | |

| Unmarried | 70 | 8.3 | 32 | 12.4 | 27 | 6.7 | 11 | 5.9 | |

| Never been married | 129 | 15.2 | 11 | 4.3 | 53 | 13.2 | 65 | 34.8 | |

| Health insurance (n, %) | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 564 | 66.7 | 123 | 47.7 | 288 | 71.8 | 153 | 81.8 | |

| No | 282 | 33.3 | 135 | 52.3 | 113 | 28.2 | 34 | 18.2 | |

| Having a regular physician (n, %) | 0.0019 | ||||||||

| Yes | 498 | 58.9 | 135 | 52.3 | 234 | 58.4 | 129 | 69.0 | |

| No | 348 | 41.1 | 123 | 47.7 | 167 | 41.6 | 58 | 31.0 | |

| Health status (n, %) | <.0001 | ||||||||

| Good | 525 | 62.1 | 97 | 37.6 | 266 | 66.3 | 162 | 86.6 | |

| Poor | 321 | 37.9 | 161 | 62.4 | 135 | 33.7 | 25 | 13.4 | |

P-values are from Chi-square tests or ANOVA tests.

Table 2. Association between acculturation variables and colorectal cancer screening, n=846.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| SL-ASIA | 1.95 | (1.33, 2.85) | 1.55 | (1.04, 2.29) | 1.46 | (0.98, 2.17) | 1.55 | (0.99, 2.43) | |

| Clusters | American | 1.81 | (1.05, 3.11) | 1.26 | (0.71, 2.21) | 1.20 | (0.68, 2.11) | 1.14 | (0.61, 2.13) |

| Bicultural | 1.31 | (0.86, 1.98) | 1.00 | (0.65, 1.56) | 0.97 | (0.63, 1.51) | 0.98 | (0.61, 1.57) | |

| Asian | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||

| Language | English | 1.74 | (0.81, 3.75) | 1.49 | (0.69, 3.24) | 1.43 | (0.66, 3.12) | 1.45 | (0.64, 3.27) |

| preference | Equal | 1.77 | (1.14, 2.75) | 1.35 | (0.86, 2.12) | 1.33 | (0.85, 2.10) | 1.32 | (0.80, 2.18) |

| Asian languages | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||

| Length of | 21+ | 2.41 | (1.52, 3.82) | 1.88 | (1.16, 3.04) | 1.72 | (1.05, 2.81) | 1.74 | (1.03, 2.95) |

| residency | 11-20 | 2.19 | (1.39, 3.44) | 1.73 | (1.09, 2.74) | 1.59 | (0.99, 2.55) | 1.58 | (0.98, 2.57) |

| 0-10 | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||

| Age at arrival | 0-20 | 3.45 | (1.66, 7.17) | 2.45 | (1.15, 5.24) | 2.23 | (1.04, 4.79) | 2.23 | (0.99, 5.00) |

| 21-30 | 2.71 | (1.50, 4.90) | 2.01 | (1.08, 3.76) | 1.82 | (0.97, 3.42) | 1.94 | (1.00, 3.77) | |

| 31-40 | 2.22 | (1.30, 3.81) | 1.57 | (0.89, 2.79) | 1.45 | (0.81, 2.58) | 1.59 | (0.86, 2.94) | |

| 41+ | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||

| Age a | 1.08 | (1.07, 1.10) | 1.08 | (1.07, 1.10) | 1.08 | (1.06, 1.10) | 1.08 | (1.06, 1.10) | |

| Insurancea (yes vsno) | 2.89 | (1.86, 4.49) | 2.27 | (1.39, 3.69) | 2.15 | (1.30, 3.56) | |||

| Regular physiciana (yes vs. no) | 1.66 | (1.06, 2.60) | 1.79 | (1.11, 2.87) | |||||

| Gendera (Female vs. male) | 1.02 | (0.69, 1.51) | |||||||

| Ethnicitya | Chinese | 1.11 | (0.68, 1.81) | ||||||

| Vietnamese | 1.30 | (0.79, 2.13) | |||||||

| Korean | REF | ||||||||

| Income a | Missing | 0.55 | (0.18, 1.68) | ||||||

| More than $100,000 | 0.83 | (0.42, 1.66) | |||||||

| $75,000-$99,999 | 0.63 | (0.29, 1.35) | |||||||

| $50,000-$74,999 | 1.28 | (0.64, 2.57) | |||||||

| $20,000-$49,999 | 0.96 | (0.54, 1.70) | |||||||

| Less than $19,999 | REF | ||||||||

| Marital status a | Married | 1.14 | (0.50, 2.60) | ||||||

| Unmarried | 1.06 | (0.39, 2.86) | |||||||

| Never been married | REF | ||||||||

| Health statusa(good vs. poor) | 1.24 | (0.80, 1.92) | |||||||

Estimates are based on the model using cluster as the acculturation measure.

Table 5. Association between acculturation and colorectal cancer screening by access to a regular physician.

| Crude n=846 |

Have a regular Physician n=498 |

No Regular Physician n=348 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| SL-ASIA | 1.46 | 0.98 2.17 | 1.02 | 0.62 1.68 | 2.56 | 1.28 5.11 | |

| Clusters | American | 1.20 | 0.68 2.11 | 0.88 | 0.45 1.71 | 2.90 | 1.00 8.45 |

| Bicultural | 0.97 | 0.63 1.51 | 0.74 | 0.44 1.24 | 1.69 | 0.73 3.93 | |

| Asian | REF | REF | REF | ||||

| Language | American | 1.43 | 0.66 3.12 | 0.84 | 0.30 2.37 | 4.20 | 1.26 13.97 |

| Preference | Bicultural | 1.33 | 0.85 2.10 | 1.39 | 0.83 2.34 | 1.20 | 0.45 3.18 |

| Asian | REF | REF | REF | ||||

| Age at | 0-20 | 2.23 | 1.04 4.79 | 1.49 | 0.60 3.71 | 5.33 | 1.28 22.18 |

| arrival | 21-30 | 1.82 | 0.97 3.42 | 1.34 | 0.63 2.83 | 3.28 | 0.98 10.96 |

| 31-40 | 1.45 | 0.81 2.58 | 0.91 | 0.46 1.81 | 3.80 | 1.21 11.96 | |

| 41+ | REF | REF | REF | ||||

Colorectal Cancer Screening

Those who were more acculturated, as indicated by having a higher SL-ASIA score, being categorized into the American cluster, speaking English and Asian language equally well, living longer length of residency in the U.S., and having a younger age at arrival, were significantly more likely to have received colorectal cancer screening in the past two years after adjusting for age (Table 2). Adjusting additionally for health insurance in Model 2 resulted in large reductions in the magnitude and significance of the association. Only SL-ASIA, length of residency, and early age at arrival remained statistically significant. Having health insurance was strongly associated with colorectal cancer screening. After adjusting for having a regular physician in Model 3, the strength of the associations decreased further. The reduction in the odds ratios was not as large as that from Model 1 to Model 2. Having a regular physician was strongly related to having had colorectal cancer screening. Model 4 adjusted additionally for gender, ethnicity, family income, marital status, and health status which yielded similar results as in the previous models.

Cervical Cancer Screening

Table 3 presents the results for the 4 models on acculturation and having had a Pap smear. When only age was adjusted, SL-ASIA, the American cluster, length of residency, language preference, and age at arrival were significantly associated with having a Pap smear in the past two years. Similar to the findings for colorectal cancer screening, the strength of the association decreased significantly in Model 2 after adjusting for having health insurance. Almost all acculturation measures were not statistically significant. The magnitude of the odds ratios were further reduced after the adjustment of having a regular physician in Model 3. Both health insurance and having a regular physician were strongly associated with having a Pap smear. After adjusting for marital status, ethnicity, income, and health status subsequently in Model 4, none of the acculturation measures were significantly associated with having had a Pap smear as also found with Model 2 and Model 3. The differences among the three ethnic groups were significant. Both Chinese and Vietnamese American women were more likely to have a Pap smear than Korean American women after adjusting for the other covariates.

Table 3. Association between acculturation variables and Pap smear, n=492.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| SL-ASIA | 1.56 | 1.03 2.37 | 1.20 | 0.77 1.85 | 0.96 | 0.61 1.52 | 1.03 | 0.62 1.72 | |

| Clusters | American | 2.29 | 1.25 4.21 | 1.54 | 0.81 2.91 | 1.36 | 0.71 2.62 | 1.59 | 0.73 3.45 |

| Bicultural | 1.26 | 0.82 1.95 | 0.98 | 0.62 1.55 | 0.95 | 0.59 1.52 | 0.94 | 0.56 1.58 | |

| Asian | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||

| Language | American | 2.62 | 1.11 6.21 | 2.03 | 0.83 4.97 | 1.78 | 0.71 4.46 | 1.94 | 0.70 5.37 |

| Preference | Bicultural | 1.59 | 0.97 2.60 | 1.14 | 0.68 1.91 | 1.04 | 0.61 1.77 | 0.90 | 0.49 1.64 |

| Asian | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||

| Length of | 21+ | 1.79 | 1.07 3.01 | 1.40 | 0.81 2.39 | 1.05 | 0.60 1.85 | 1.22 | 0.67 2.23 |

| residency | 11-20 | 2.16 | 1.41 3.31 | 1.76 | 1.13 2.75 | 1.39 | 0.87 2.22 | 1.26 | 0.77 2.07 |

| 0-10 | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||

| Age at arrival | 0-20 | 1.99 | 0.88 4.52 | 1.23 | 0.52 2.92 | 0.80 | 0.33 1.95 | 0.83 | 0.33 2.09 |

| 21-30 | 2.58 | 1.33 5.03 | 1.72 | 0.86 3.45 | 1.26 | 0.61 2.59 | 1.21 | 0.57 2.59 | |

| 31-40 | 2.30 | 1.23 4.28 | 1.52 | 0.78 2.95 | 1.24 | 0.63 2.45 | 1.32 | 0.64 2.70 | |

| 41+ | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||

| Age a | 1.03 | 1.01 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.02 1.05 | 1.03 | 1.01 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.01 1.05 | |

| Insurancea (yes vs.no) | 3.41 | 2.25 5.16 | 2.14 | 1.34 3.42 | 1.70 | 1.02 2.85 | |||

| Regular Physiciana (yes vs. no) | 2.78 | 1.77 4.35 | 2.60 | 1.60 4.22 | |||||

| Marital status a | Married | 2.43 | 1.14 5.18 | ||||||

| Unmarried | 1.71 | 0.66 4.43 | |||||||

| Never been married | REF | ||||||||

| Ethnicity a | Chinese | 1.94 | 1.14 3.29 | ||||||

| Vietnamese | 1.91 | 1.09 3.36 | REF | ||||||

| Korean | 0.85 | 0.28 2.52 | |||||||

| Income3 Missing | 1.04 | 0.45 2.39 | |||||||

| More than $100,000 | 1.45 | 0.59 3.52 | |||||||

| $75,000-$99,999 | 1.23 | 0.56 2.72 | |||||||

| $50,000-$74,999 | 1.08 | 0.60 1.96 | |||||||

| $20,000-$49,999 | REF | ||||||||

| Less than $19,999 | REF | ||||||||

| Health status3 (good vs. poor) | 1.29 | 0.81 2.07 | |||||||

Estimates are based on the model using clusters as the acculturation measure.1.08

Breast cancer screening

Similar to the other cancer screenings, the association between acculturation and having had a mammogram decreased significantly after adjusting for the health access variables (Table 4). In Model 1 where only age was included as a covariate, SL-ASIA, acculturation clusters, length of residency, and age at arrival were significantly associated with mammogram use in the past two years. Model 2 adjusted for health insurance, and Model 3 additionally adjusted for having a regular physician. Results from these two models were similar in that the association between acculturation and receipt of a mammogram were not significant for most measures. The reduction in the association was more obvious from Model 1 to Model 2 than that from Model 2 to Model 3. Inclusion of the remaining covariates did not change the association as seen in Model 4.

Table 4. Association between acculturation variables and mammogram, n=492.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||

| SL-ASIA | 1.88 | 1.23 2.89 | 1.49 | 0.96 2.33 | 1.25 | 0.79 1.97 | 1.29 | 0.77 2.15 | |

| Clusters | American | 2.16 | 1.19 3.91 | 1.50 | 0.81 2.80 | 1.35 | 0.72 2.53 | 1.54 | 0.75 3.16 |

| Bicultural | 1.53 | 0.98 2.39 | 1.23 | 0.78 1.96 | 1.20 | 0.75 1.93 | 1.17 | 0.71 1.94 | |

| Asian | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||

| Language | American | 1.15 | 0.51 2.63 | 0.87 | 0.37 2.03 | 0.75 | 0.32 1.77 | 0.90 | 0.35 2.28 |

| Preference | Bicultural | 1.56 | 0.96 2.54 | 1.14 | 0.68 1.89 | 1.05 | 0.62 1.77 | 1.08 | 0.61 1.93 |

| Asian | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||

| Length of | 21+ | 2.11 | 1.25 3.57 | 1.71 | 0.99 2.95 | 1.38 | 0.78 2.42 | 1.51 | 0.82 2.76 |

| residency | 11-20 | 2.49 | 1.62 3.83 | 2.08 | 1.34 3.24 | 1.73 | 1.09 2.75 | 1.82 | 1.12 2.95 |

| 0-10 | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||

| Age at arrival | 0-20 | 3.10 | 1.33 7.23 | 2.12 | 0.88 5.13 | 1.48 | 0.60 3.68 | 1.50 | 0.59 3.82 |

| 21-30 | 2.83 | 1.44 5.57 | 1.99 | 0.98 4.04 | 1.52 | 0.74 3.13 | 1.30 | 0.61 2.79 | |

| 31-40 | 4.05 | 2.10 7.82 | 2.93 | 1.47 5.85 | 2.52 | 1.24 5.10 | 2.19 | 1.04 4.61 | |

| 41+ | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||

| Age a | 1.06 | 1.04 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.05 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.04 1.08 | 1.06 | 1.04 1.09 | |

| Insurancea (yes vs.no) | 3.14 | 2.05 4.82 | 2.07 | 1.28 3.35 | 2.09 | 1.23 3.55 | |||

| Regular physiciana(yes vs. no) | 2.49 | 1.57 3.94 | 2.27 | 1.40 3.69 | |||||

| Marital status a | Married | 1.82 | 0.83 3.98 | ||||||

| Unmarried | 1.27 | 0.48 3.41 | |||||||

| Never been married | REF | ||||||||

| Ethnicity a | Chinese | 1.24 | 0.74 2.08 | ||||||

| Vietnamese | 1.10 | 0.63 1.91 | |||||||

| Korean | 1.37 | 0.45 4.24 | |||||||

| Income3 Missing | 1.10 | 0.50 2.41 | |||||||

| More than $100,000 | 1.91 | 0.82 4.45 | |||||||

| $75,000-$99,999 | 1.72 | 0.78 3.79 | |||||||

| $50,000-$74,999 | 1.72 | 0.78 3.79 | |||||||

| $20,000-$49,999 | 1.64 | 0.89 3.02 | |||||||

| Less than $19,999 | REF | ||||||||

| Health status3 (good vs. poor) | 0.98 | 0.62 1.56 | |||||||

Estimates are based on the model using clusters as the acculturation measure 0.98

We tested for interaction between all measures of acculturation and ethnicity, health insurance, and having a regular physician across all cancer screening outcomes. Significant interaction was only found between having a regular physician and all acculturation variables, with the exception of length of residency, for colorectal cancer screening. The stratified results are presented in Table 5. Associations between acculturation and colorectal cancer screening were observed only among participants who did not have a regular physician.

Discussion

This current study is one of the first to employ multiple acculturation measures to examine the relationship between acculturation and three different types of cancer screenings among three large Asian ethnic groups (Chinese, Korean and Vietnamese Americans) to capture the complexity of acculturation process. Previous studies on acculturation and cancer screening behaviors among Asian Americans have focused on one cancer screening outcome, used one or two acculturation measures, or usually examined a single Asian ethnic group. Using multiple indicators of acculturation, we found that a greater level of acculturation was associated with a higher likelihood of receiving cancer screening. Similar trends were observed across all acculturation measures that were used in the study. This association was most significant when only adjusting for age and decreased in its significance and magnitude after adjusting for covariates, especially when adjusting for health insurance and having a regular physician.

Health insurance had a large confounding effect on the association between acculturation and all cancer screenings. Adjusting for health insurance yielded a large reduction in the strength of association both in magnitude and significance. Those who had health insurance or had a regular physician were significantly more likely to receive the aforementioned colorectal, cervical, and breast cancer screening in the past two years. This finding is consistent with a study of recent immigrants that included multiple racial and ethnic groups [21].

Colorectal cancer screening

Our findings showed that acculturation, regardless of the acculturation measure used, is positively associated with having colorectal cancer screening. This trend is consistent with previous studies among Hispanics as well as Asian Americans [5,22-24]. These previous studies among Asian Americans found that a higher percentage of life in the U.S., better English proficiency, and a higher summary score of SL-ASIA were associated with a higher likelihood of having colorectal cancer screening [5, 24, 25]. However, our findings were inconsistent with a study that used a different acculturation scale (Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics) among Latino and Vietnamese [12]. The association became not significant for most measures of acculturation after adjusting for various covariates, especially having health insurance and a regular physician. The reduction of association after adjusting for health care factors was also noted by an earlier study among Hispanic immigrants where the association between acculturation and colorectal cancer screening did not exist after adjusting for health care utilization and other demographic variables [23]. While most studies have examined acculturation and a physician’s recommendation as independent predictors for colorectal cancer screening among Asian Americans, the interaction between these two factors were rarely reported [5, 25, 26]. We found significant interactions between four acculturation measures and having or not having a regular physician. The stratified analysis results in the current study suggest that the association between acculturation and colorectal cancer screening was only present among those who did not have a regular physician. Health care factors such as a physician’s recommendation, having a usual source of care, and use of other preventive health services have been documented to be associated with colorectal cancer screening [5, 12, 25, 27]. Given the strong impact of a physician’s recommendation on colorectal cancer screening, one possible explanation for the different observed effects of acculturation on colorectal cancer screening may be that those who had a regular physician received a doctor’s recommendation, whereas those who did not have a regular physician had to initiate colorectal cancer screening based on their knowledge or attitudes towards cancer screening. For the latter scenario, acculturation may have played a role in that initiation process.

Cervical cancer screening

Previous studies on acculturation and the receipt of a Pap smear among Asian Americans have had conflicting results due to inconsistencies in measures of acculturation and Asian subgroups. English proficiency was positively associated with having a Pap smear among Chinese American and Korean American women with both studies adjusting for health insurance [6, 8, 28]. No association was found between percentage of life in the U.S. and having had a recent Pap smear among Korean Americans [8]. A similar time-related measure, years of life in the U.S. was found to have a marginally significant association with having a recent Pap smear [9]. Our study found some associations between acculturation and having a Pap smear in the age-adjusted models but none of the associations were significant after adjusting for health care factors and socio-demographic characteristics. This is consistent with a study among Mexican American women where the association between English proficiency and having a recent Pap smear disappeared after adjusting for age, socioeconomic status, and health insurance [29]. The relationship between acculturation and having a Pap smear with respect to health insurance is complicated. A large scale national survey with multiple racial and ethnic groups found that the screening rates were similar between U.S.-born and foreign-born women when they were insured, but the screening rate was significantly lower among uninsured foreign-born women than their uninsured U.S.-born counterparts [30]. In the current study, significant ethnic differences were seen for having a Pap smear test with Korean American women being significantly less likely to have a Pap smear than Chinese and Vietnamese women.

Breast cancer screening

Although mammography is one of the most frequently studied cancer screenings among Asian Americans, results are highly inconsistent across different acculturation measures and Asian subgroups. SL-ASIA and years of living in the U.S. were found to be significantly associated with having a mammogram but not English proficiency [9,31]. Percentage of life in the U.S. was found to be associated with ever having a mammogram among Korean Americans in California, but not associated with having had a recent mammogram among Korean Americans in Maryland [8, 9]. Our study found that SL-ASIA, the American cluster, length of residency, and age at arrival were significantly associated with mammogram use in the past two years after adjusting for age. In addition, the association was found to decrease significantly after adjusting for access to health care variables similar to the other cancer screening outcomes. Our study did not find a significant association between all acculturation measures and having a mammography in the past two years and after adjusting for all covariates.

Limitations

There are several limitations of our study regarding sampling, measurement, and data collection. First, the generalizability of our findings to other populations that are more acculturated is limited given that we used a non-random sample for our hard-to-reach population of Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese Americans in Maryland and that most of our participants were first generation immigrants. Second, all cancer screening outcomes were self-reported and may be prone to recall bias. It is possible that some ethnic difference observed in our study may be partly due to self-report patterns. Third, our sample included participants who were below recommended age for cancer screenings. Since most of the cancer screening recommendations were age dependent, a larger sample with a sufficient proportion of older participants may overcome this weakness. Forth, this study is cross-sectional in design and cannot be used to infer causation.

Despite the limitations, the current study is one of the first to employ multiple acculturation measures to examine the relationship between acculturation and three different types of cancer screening among Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese Americans. We found that the five different types of acculturation measures behaved similarly in relation to the three types of cancer screening examined. Also, the pattern of the associations between acculturation and cancer screenings were similar across three different types of cancer screenings. We were not able to detect interaction between the acculturation measures and ethnicity. Therefore, our study concludes that the type of acculturation measure used, type of cancer screening examined, and ethnicity do not greatly affect the association between acculturation and cancer screening. The main findings from our comprehensive examination suggest that acculturation is strongly associated with cancer screening in the unadjusted models. In addition by conducting a series of model building, we found that most of the associations were highly confounded by health care factors. Finding significant interaction between acculturation and having a regular physician for colorectal cancer screening also adds to the literature by helping to elucidate the underlying mechanism for the association between acculturation and receipt of colorectal cancer screening. This finding also suggests a potential role of having or not having a regular source of care with respect to receiving colorectal cancer screening.

Considering the fact that Asian Americans are far less likely to have health insurance and a regular source of care compared to non-Hispanic Whites [32], it may be important to provide linguistically and culturally appropriate interventions or educational programs for Asian Americans to raise awareness about the importance of cancer screening. Such interventions and programs could also provide information on the availability of local safety net clinics or low cost clinics, especially among less acculturated recent Asian immigrants.

Figure 1. Acculturation Clustersa Relative Distribution of Variables (z-scores).

a Cluster 1 is Asian, Cluster 2 is Bicultural, and Cluster 3 is American.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (R25CA129042).

Contributor Information

Sunmin Lee, Associate Professor, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Maryland School of Public Health, 2234C SPH Bldg, College Park, MD 20742, sunmin@umd.edu; Phone: 301-405-7251; Fax: 301-314-9366.

Lu Chen, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, 1959 NE Pacific Street, Health Sciences Building F-262, Box 357236, Seattle, WA 98195, cheryllulu@gmail.com; Phone: 240-505-9324.

Mary Y. Jung, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Maryland School of Public Health, 0232 SPH Bldg, College Park, MD 20742, maryyjung@gmail.com; Phone: 301-405-7218.

Lourdes Baezconde-Garbanati, Associate Professor, Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine at University of Southern California, 2001 N. Soto St, 3rd Floor, MC 9239, Los Angeles, CA 90033, baezcond@usc.edu; Phone: 323-442-8231.

Hee-Soon Juon, Associate Professor, Department of Health, Behavior, and Society, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 624 N. Broadway, #704, Baltimore, MD 21205, hjuon@jhsph.edu; phone: 410-614-5.

References

- 1.McCracken M, Olsen M, Chen MS, et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese ethnicities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(4):190–205. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.cancer.org/Healthy/FindCancerEarly/CancerScreeningGuidelines/american-cancer-society-guidelines-for-the-early-detection-of-cancer.

- 3.Klabunde C, Brown M, Ballard-Barbash R, et al. Cancer Screening- United States, 2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pourat N, Kagawa-Singer M, Breen N, Sripipatana A. Access versus acculturation: Identifying modifiable factors to promote cancer screening among Asian American women. Med Care. 2010;48(12):1088–1096. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f53542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang TS, Solomon LJ, McCracken LM. Barriers to fecal occult blood testing and sigmoidoscopy among older Chinese-American women. Cancer Pract. 2001;9(6):277–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.96008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ji CS, Chen MY, Sun J, Liang W. Cultural views, English proficiency and regular cervical cancer screening among older Chinese American women. Women Health Iss. 2010;20(4):272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yi JK. Acculturation and Pap smear screening practices among college-aged Vietnamese women in the United States. Cancer Nurs. 1998;21(5):335–341. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199810000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juon HS, Seo YJ, Kim MT. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Korean American elderly women. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2002;6(4):228–235. doi: 10.1054/ejon.2002.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McPhee SJ, Stewart S, Brock KC, Bird JA, Jenkins CN, Pham GQ. Factors associated with breast and cervical cancer screening practices among Vietnamese American women. Cancer Detect Prev. 1997;21(6):510–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohler B, Ward E, McCarthy B, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer featuring tumors of the brain and other nervous system, 1975-2007. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(9):714–736. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Colorectal Cancer Screening Saves Lives. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/Features/VitalSigns/CancerScreening/

- 12.Walsh JME, Kaplan CP, Nguyen B, Gildengorin G, McPhee SJ, Pérez-Stable EJ. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in Latino and Vietnamese Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):156–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30263.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cervical Cancer Screening. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/basic_info/screening.htm.

- 14.Lee HY, Ju E, Vang PD, Lundquist M. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Asian American women and Latinas: Does race/ethnicity matter? J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(10):1877–1884. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deapen D, Liu L, Perkins C, Bernstein L, Ross RK. Rapidly rising breast cancer incidence rates among Asian-American women. Int J Cancer. 2002;99(5):747–750. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Cancer Institute Breast Cancer Screening. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/screening/breast/healthprofessional/page1.

- 17.Ma GX, Goa W, Lee S, Wang MQ, Tan Y, Shive SE. Health seeking behavioral analysis associated with breast cancer screening among Asian American women. Int J Women Health. 2012;4:235–243. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S30738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suinn RM, Rickard-Figueroa K, Lew S, Vigil P. The Suinn-Lew Asian Self-Identity Acculturation scale: An initial report. Educ Psychol Meas. 1987;47(2):401–407. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraley C, Raftery AE. How many clusters? Which clustering method? Answers Via model-based cluster analysis. Comput J. 1998;41(8):578–588. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan MF, Ho A, Day MC. Investigating the knowledge, attitudes and practice patterns of operating room staff towards standard and transmission-based precautions: results of a cluster analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(8):1051–1062. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee S, O’Neill A, Park J, Scully L, Shenassa E. Health insurance moderates the association between immigrant length of stay and health status. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(2):345–349. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9411-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson-Kozlow M. Colorectal cancer screening of Californian adults of Mexican origin as a function of acculturation. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(4):454–461. doi: 10.1007/s10903-009-9236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah M, Zhu K, Potter J. Hispanic acculturation and utilization of colorectal cancer screening in the United States. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30(3):306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maxwell AE, Bastani R, Warda US. Demographic predictors of cancer screening among Filipino and Korean immigrants in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(1):62–68. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Honda K. Factors associated with colorectal cancer screening among the US urban Japanese population. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):815–822. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teng EJ, Friedman LC, Green CE. Determinants of colorectal cancer screening behavior among Chinese Americans. Psychooncology. 2006;15(5):374–381. doi: 10.1002/pon.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening behaviors among average-risk older adults in the United States. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19(4):339–359. doi: 10.1007/s10552-007-9100-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu ES, Kim KK, Chen EH, Brintnall RA. Breast and cervical cancer screening among Chinese American women. Cancer Pract. 2001;9(2):81–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009002081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suarez L. Pap smear and mammogram screening in Mexican-American women: The effects of acculturation. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(5):742–746. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.5.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrasquillo O, Pati S. The role of health insurance on Pap smear and mammography utilization by immigrants living in the United States. Prev Med. 2004;39(5):943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang TS, Solomon LJ, McCracken LM. Cultural barriers to mammography, clinical breast exam, and breast self-exam among Chinese-American women 60 and older. Prev Med. 2000;31(5):575–583. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clough J, Lee S, Chae DH. Barriers to health care among Asian immigrants in the United States: A traditional review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(1):384–403. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]