Abstract

Cranio-lenticulo-sutural dysplasia (CLSD) is a rare autosomal recessive syndrome manifesting with large and late closing fontanels and calvarial hypomineralization, Y-shaped cataracts, skeletal defects, and hypertelorism and other facial dysmorphisms. The CLSD locus was mapped to chromosome 14q13-q21 and a homozygous SEC23A F382L missense mutation was identified in the original family. Skin fibroblasts from these patients exhibit features of a secretion defect with marked distension of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), consistent with SEC23A function in protein export from the ER. We report an unrelated family where a male proband presented with clinical features of CLSD. A heterozygous missense M702V mutation in a highly conserved residue of SEC23A was inherited from the clinically unaffected father, but no maternal SEC23A mutation was identified. Cultured skin fibroblasts from this new patient showed a severe secretion defect of collagen and enlarged ER, confirming aberrant protein export from the ER. Milder collagen secretion defects and ER distention were present in paternal fibroblasts, indicating that an additional mutation(s) is present in the proband. Our data suggest that defective ER export is the cause of CLSD and genetic element(s) besides SEC23A may influence its presentation.

Keywords: Cranio-lenticulo-sutural dysplasia, craniofacial development, skull hypomineralization, ER export, SEC23A

Introduction

Craniofacial development is a complex process and both genetic and environmental insults can alter it, resulting in congenital malformations. As craniofacial malformations are present in 75% of all human congenital defects (1), understanding normal and abnormal morphogenesis is important for improving the care and life of affected individuals. We described CLSD (Boyadjiev-Jabs syndrome, OMIM 607812) as a new autosomal recessive genetic syndrome characterized by facial dysmorphisms, late closing fontanels, cataracts and skeletal defects (2). By genome-wide linkage screening we mapped the locus to chromosome 14q13-q21, and identified a homozygous mutation F382L in SEC23A as the cause of CLSD (3). This mutation precludes the formation of SEC23A/SEC31 complex and causes inefficient export of secretory proteins from the ER resulting in its gross dilatation.

We have identified and characterized a Caucasian male patient with clinical features of CLSD in which we found only one mutant SEC23A allele of paternal origin. Our data suggest that digenic inheritance may be implicated in CLSD.

Materials and methods

Subjects and sample preparation

The proband and both parents were enrolled in this study under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California Davis. Clinical records, X-ray images and results of laboratory testing were collected and stored in a secure database. Venous blood samples were obtained by peripheral phlebotomy and samples for DNA extraction and for immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines were collected. Total genomic DNA was extracted with the Puragene DNA extraction kit (Gentra Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) as described in the manufacturer’s protocol. Human B-lymphocytes were immortalized by transformation with Epstein-Barr virus according to established procedures (4).

Skin biopsies were obtained from the medial aspect of the forearm with a punch biopsy tool (Acuderm, Inc., Ft. Lauderdale, FL) after local anesthesia with 1% Lidocaine (Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL).

Molecular analyses of the SEC23A gene and other COPII genes

Total lymphocyte RNA from the affected child and his parents was extracted and purified using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was prepared with Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). All mRNA and cDNA transcripts used for analysis of SEC23A were identified using the Human Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu). Primers sequences based upon GenBank accession code NM_006364 were designed to amplify the complete coding region of SEC23A from cDNA including the 5'- and 3'-untranslated regions (UTR) in four overlapping segments. Sequencing was carried out by the dideoxy chain termination method with the Sequenase version 2.0 DNA sequencing kit (US Biochemical) with a relevant primer. A custom TaqMan assay (Applied Biosystems) for the c.2104A>G mutation was designed and 186 control individuals were tested. All sequences were reviewed by at least two independent investigators. Proband’s SEC23B, SEC 31A and SEC13 were also sequenced in a similar way.

Immunoblotting

Protein lysates were resolved in SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membrane. Membranes coated with primary antibodies were incubated with protein A-horseradish peroxidase for visualization using ECL Plus (5). For assessment of procollagen secretion defect, culture media (10 ml) was concentrated by TCA (10%) precipitation and 200 µg of total proteins was applied to SDS-PAGE and processed for immunoblotting. Total cell lysates were prepared in a RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% Sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% SDS, 0.5% Triton-X100) and 20 µg of total proteins were applied to SDS-PAGE and processed for immunoblotting.

Immunofluorescence and Electron Microscopy

Immunofluorescence and electron microscopy were performed as previously described (6).

Results

Clinical phenotypes

An 8 month old boy was referred for a clinical genetic evaluation presenting with a very large anterior fontanel, hypertelorism, strabismus, valvular pulmonic stenosis, and motor delay. The proband was the third child of healthy non-consanguineous 34 year old G3P2002 mother and 37 year old father. At birth, hypertelorism and a heart murmur were present and he had poor suck improved after a frenulectomy of the anteriorly displaced frenula linguae. Cardiac assessment at 2 months revealed moderate valvular pulmonary stenosis. Brain MRI at 4 months documented hypoplastic optic nerves, but normal brain morphology. He had surgery for bilateral exotropia at 6 months and had bilateral optic atrophy and a double-ring sign, a characteristic horizontal splitting of the anterior lens capsule with expansion of intercellular spaces in the lens epithelium (7). A single episode of tonic/clonic febrile seizure occurred at 30 months, at 4 years he had two petit mal seizures. EEG documented nonspecific abnormal brain wave pattern. High resolution karyotype, subtelomeric analysis, FISH studies for 22q11 and tetrasomy 12p were all normal. Isoelectric focusing of transferrin was normal and excluded a protein glycosylation defect.

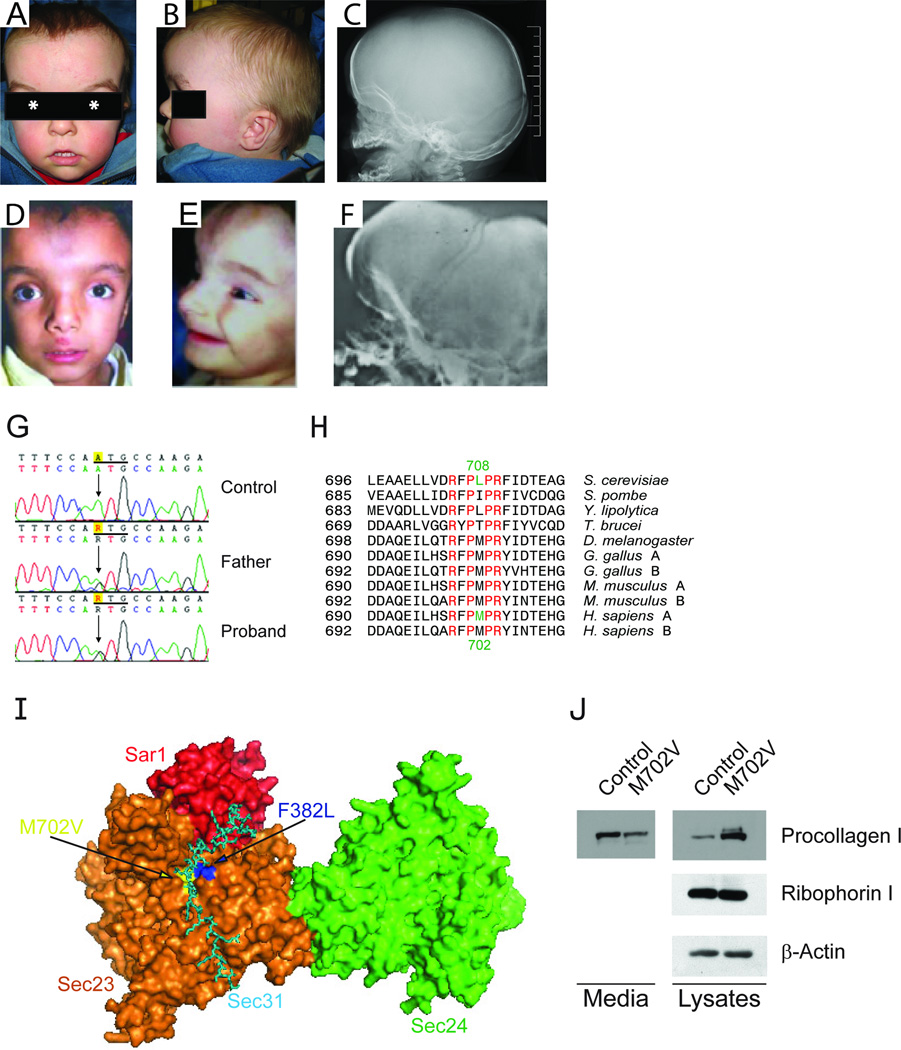

The proband has a characteristic facial appearance with a strong resemblance to the features of the original patients (Fig. 1A–F). At eight months, his weight, length and head circumference were all at the 50 percentile. His head was with prominent forehead and occiput and the anterior fontanel was open and unusually large (measuring 8cm by 5 cm) and extending to the forehead as a result of the broad metopic suture. The skin over the forehead was with a small capillary hemangioma and prominent vasculature, and abnormal pigmentation as in the original patients (2). These findings became less evident with age (Fig. S1). While such forehead skin changes are not uncommon and may be present in both healthy children and patients with other dysmorphic syndromes, they appear to be a consistent feature of CLSD. We are aware of several dysmorphic syndromes presenting with delayed closure of the fontanels, macrocephaly and similar skin abnormalities that are distinct from CLSD (8, 9).

Figure 1.

The craniofacial features of a newly identified CLSD patient at 21 month (A, B, and C) are very similar to those of known CLSD patients (D, E, and F) (2, 3). They have high and prominent forehead, with increased vascular marking in the area of the open anterior fontanel, similar shape of the eyebrows, obvious hypertelorism (the center of the pupil is marked by asterisk) and similar shape of the nose with wide and prominent nasal bridge and anteverted nares. The philtrum is long and the mouth is large and with thin upper lip in both cases. Lateral skull x-rays document large and hypomineralized calvaria in the area of the anterior fontanel (C and F). (G) Illustration of the c.2104A>G mutation (ATG>GTG, M702V). (H) Sequence alignment of SEC23. Invariant residues are shown in red. The human M702 residue shown in green is conserved in higher eukaryotes and corresponds to the yeast L708 residue shown in green. A and B after the name of indicated species represent SEC23A and SEC23B, respectively. (I) X-ray crytallographic model of a yeast Sec31 fragment (cyan) in complex with yeast Sar1p (red) and yeast Sec23p (orange) (10), with Sec24p (light green) included based on the structure of the Sar1p-Sec23p-Sec24p complex modified from the previous report (17). Because human F382 (yeast F380) is buried under the surface of the structure, two residues adjacent to F302 were colored blue and labeled “F382L”. The positions of the yeast residues corresponding to human M702 and P703 are colored yellow and labeled “M702V”. (J) Secretion defect of procollagen in M702V cells was shown by using immunoblotting. Ribophorin 1 and β-actin were also probed as loading controls.

At 21 months, his height was below the 3rd centile (77 cm), weight was at the 3rd centile (10 kg) and the head was macrocephalic with a circumference above 97 percentile (51.5cm). His anterior fontanel remained open measuring 3 cm ×3 cm. At 4 years and 6 months with supplementary feedings his weight and height were at the 25th percentiles and he remained macrocephalic. There was scalp hypotrichosis and the anterior hair line was high. The eyebrows were with scant medial portions and a peak in the center. He had prominent hypertelorism with interpupillary distance, measuring above the 97 percentile and downslanting palpebral fissures. A mild maxillary hypoplasia was present at 21 months. The ears were asymmetric, low set and slightly posteriorly rotated. The nose was wide and with a prominent nasal bridge and slightly anteverted nares. The philtrum was long and well formed and the upper lip was thin. Dentition was appropriate for age with first front upper incisor erupting at 5 month. Oral examination documented high arched palate, bifid ubula, and partial cleft of soft palate. There was no swallowing difficulty, nor hypernasal voice. There were no limb anomalies.

Skull films at 8 months of age documented large unossified anterior fontanel, hypertelorism and mild diffuse osteopenia. Macrocephaly, frontal and occipital bossing and widely open anterior fontanel were evident at 21 months. Bone age was appropriate but hand films showed carpal epiphyseal dissociation with carpal ossification delay. Coxa valga was present and the iliac wings were high and narrow as in the originally described patients. Vertebral bodies were normal.

Developmental assessment at 21 months estimated 5 month global development delay. He had a very short attention span. Formal assessment at 4 years and 6 months documented a moderate global developmental delay and behavioral patterns consistent with PDD-NOS.

The clinical and skeletal features of this patient were similar to the original CLSD cases (Fig. 1A–F). However, the eye phenotypes differ. Esotropia, bilateral optic atrophy and double-ring sign were present in the new case but to date no cataracts have been detected. Thus, the major diagnostic features of CLSD are large and late closing anterior fontanel and hypertelorism while the ocular component is variable. Interestingly, other previously undescribed clinical features were present in the new case such as anterior frenulum linguae requiring frenulectomy, gastroesophageal reflux with postnatal failure to thrive, macrocephaly, valvular pulmonic stenosis and osteopenia.

Molecular Genetics

Sequencing of SEC23A lymphoblast cDNA of the proband identified a novel heterozygous SEC23A M702V mutation in the proband. This mutation was inherited from the unaffected father and was not present in 372 Caucasian control chromosomes. No mutations were identified in the coding and the 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions of both maternal SEC23A. Deletion of a maternal allele was excluded by the presence of many normal polymorphic single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and real-time PCR analysis. The methionine at position 702 is invariably conserved in all higher eukaryotes (Fig. 1G–I). The crystal structure of yeast Sec23-Sec31 fragment demonstrated that yeast Sec23 L708 residue corresponding to human SEC23A M702 residue interacts with yeast Sec31 L925 residue (10). Thus, we predict that this novel M702V mutation disturbs the ER export by preventing normal interaction of SEC23 with SEC31 (Fig. 1I).

Cellular phenotypes

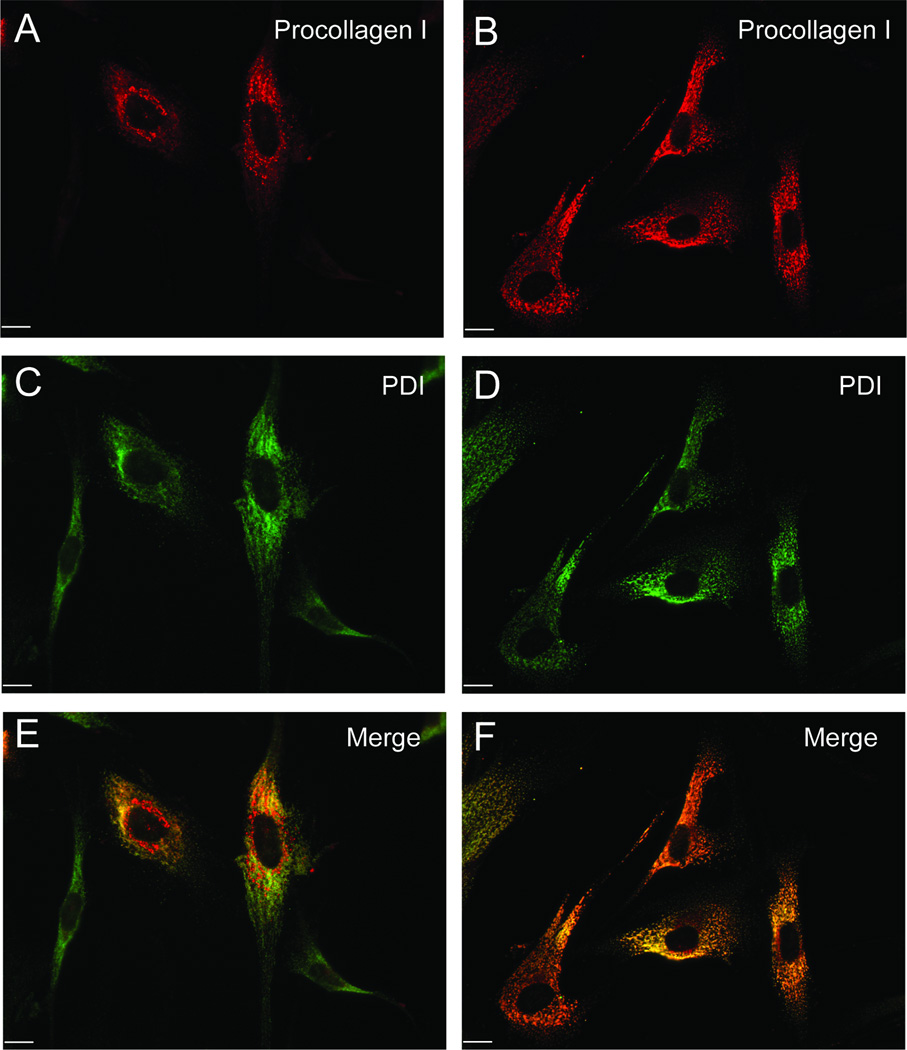

Fibroblast phenotypes of the F382L case are characterized by dilatation of the ER due to an ER export defect (3, 6). To test whether the M702V mutation causes ER accumulation of secretory proteins, we monitored collagen secretion in the patient’s fibroblasts. We found a much reduced level of collagen in the culture media of M702V cells compared to control cells (Fig. 1J). As this may reflect either a secretion defect, or reduced collagen expression in the mutant cells, we compared the intracellular pools of collagen from total cell lysates. Ribophorin I and β-actin were probed as loading controls. M702V cells contained significantly more collagen than control cells (Fig. 1J), confirming that reduction of collagen in the media was not caused by reduced collagen expression. We reasoned that the point of collagen secretion block imposed by M702V SEC23A is at the ER exit sites. Thus, we expected accumulation of collagen in the ER. To identify the intracellular compartment accumulating collagen, we performed immunofluorescent labeling with antibodies for a procollagen COL1A1(LF67) (11) and an ER marker, PDI (Fig. 2). A majority (73.4%) of M702V cells displayed extensive co-localization of collagen with PDI, while about 20% of control cells showed co-localization (Fig. 2). These data suggest that M702V cells are indeed defective in collagen secretion due to an ER export block.

Figure 2.

ER retention of procollagen. Intracellular procollagen (red, A and B) and PDI (green, C and D) were visualized using standard confocal immunofluorescent microscopy. Colocalization of procollagen and PDI is evident (F). Scale bars are 10 µm.

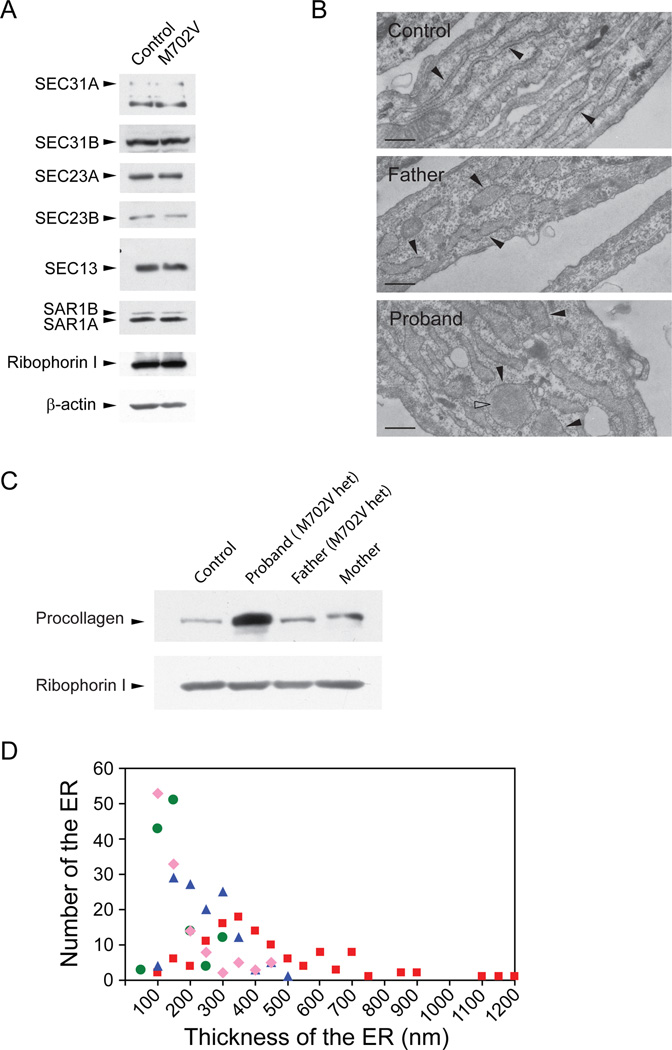

To see whether the levels of SEC23A, SEC23B, SEC31A, SEC31B, and SEC13 are altered due to an additional mutation, we monitored the expression levels of these proteins both in control and M702V fibroblasts by immunoblotting (Fig. 3A). These proteins were present at normal levels, suggesting that null mutations are not present in these COPII components. RT-PCR DNA sequencing did not find mutations in SEC23B, SEC31A, and SEC13 of the proband.

Figure 3.

Involvement of other allele(s) in CLSD. Cellular lysates of indicated cells were prepared, resolved by SDS-PAGE, and processed for immunoblotting. Ribophorin 1 or β-actin was probed as loading controls (A and C). The SAR1 antibody we used preferentially recognized SAR1A over SAR1B. (B) Electron micrographs of indicated fibroblasts. Rough endoplasmic reticulum studded with ribosomes was marked by closed arrowheads. Open arrowhead represents electron dense materials. Scale bars are 500 nm. (D) Thickness of the tubular ER was measured from the electron micrographs. We selected one or two thickest ER tubules from each cell for measurement. 100 nm in the X axis represents a thickness that is larger than 50 nm but equal to or less than 100 nm. Green circles represent for control cells, pink diamonds for maternal cells, blue triangles for paternal cells, and red squares for the patient’s cells. Averages for thickness of ER cisternae for control, maternal, paternal and the patient’s cells are 129 ± 58 (n=127), 150 ± 101 (n=125), 222 ± 87 (n=127), and 414 ± 228 nm (n=119), respectively.

If two defective alleles in the secretory pathway synthetically interact to cause the disease, we expect a more prominent secretion defect in the proband’s cells than in the parental cells. Indeed, the fibroblasts of the proband accumulated more collagen than control and parental fibroblasts (Fig. 3C). In addition, both parental fibroblasts accumulated slightly more collagen than control (Fig. 3C). To quantify an ER export defect, we measured the thickness of ER cisternae from electron micrographs (Fig. 3B and D). Because the majority of control cells have about 100 to 150 nm thick ER cisternae, an ER cisterna thicker than 150 nm was considered to be distended. Based on this criterion, about 24% of control, 31% of maternal, 73% of paternal, and 93% of the patient’s ER cisternae were distended. While the ER cisternae of paternal and the proband’s cells are statistically significantly distended (Student t-test, P<0.0001 for both lines), compared to the control cells, the maternal cells were not. Furthermore, the proband’s cells were also more distended than parental cells with statistical significance (Student t-test, P<0.0001 for both lines). The maximum thickness of control, maternal, paternal, and the patient’s ER cisternae reached about 300 nm, 450 nm, 500 nm, and 1,200 nm, respectively (Fig. 3D). These results indicate that the paternal M702V SEC23A mutation and an unknown mutation either in another COPII component or in a cargo protein (i.e., procollagen) interact synthetically to dilate the ER cisternae of the proband’s cells far more than parental ER cisternae in frequency and in magnitude.

DISCUSSION

We have identified a male patient with craniofacial and skeletal features characteristic of CLSD and a paternally inherited SEC23A mutation. Fibroblasts obtained from this patient display a collagen secretion defect and excessive accumulation of secretory molecules in the lumen of the ER as indicated by ER distension. These cellular phenotypes faithfully reproduce the previous observations (3), confirming that the ER-to-Golgi trafficking is intimately interwoven with craniofacial and skeletal development.

Mineralization of extracellular matrix (ECM) in bones and teeth is a key process in bone formation (12). Because collagen is the most abundant protein in ECM, a decreased amount of collagen in the ECM will lead to skeletal dysplasia and skull underossification. In addition, in the presence of macrocephaly one must consider that brain growth can also contribute to enlargement of the anterior fontanel.

Deletion of Bbf2h7, an upstream regulator of Sec23a, caused 80% reduction of Sec23a and Bbf2h7 knockout mice showed hypoplasia of craniofacial bones and a reduction in the cartilage ECM in limbs, vertebrae and ribs (13), corroborating our findings that deficit of Sec23a results in collagen/ECM defects in mice. Similar cellular phenotypes have been observed in Caenorhabditis elegans sec-23 mutants and in Danio rerio sec23a, or sec23b mutants. These mutants fail to secrete ECM including collagen (3, 14–16). These cellular phenotypes observed in C. elegans and in D. rerio contribute to prominent defects of (exo)skeletal morphogenesis at the organism level (3, 14–16). In conclusion, these results suggest that SEC23A is a crucial regulator of ECM trafficking.

The M702V mutation is responsible for the symptoms of the current CLSD case based on the following observations. First, the M702 residue is located in the SEC23A-SEC31 interface (Fig. 1I). Second, the ER of the paternal fibroblasts (M702V carrier) is distended, demonstrating an obvious ER export defect. This defect is expected from a mutation disrupting SEC23-SEC31 interaction. However, it is unlikely that the M702V mutation is solely responsible for the clinical phenotype because the proband’s father has a mild ER distention and a normal craniofacial and skeletal morphology. Thus, apart of the possibility of maternal SEC23A mutation that has escaped our detection, digenic inheritance with one mutant allele involving M702V SEC23A and a second mutation in other COPII subunit or a cargo molecule (i.e., collagen) may be responsible for the CLSD syndrome in this individual.

The current patient shares many important phenotypes with the F382L patients. However, some differences exist between the original patients and the new case. For example, unlike the patients with F382L mutation, the patient with M702V mutation has macrocephaly, valvular pulmonic stenosis, a bifid uvula, cleft palate, bilateral optic atrophy, seizures, gastroesophageal reflulx, postnatal failure to thrive and mild osteopenia. In addition, the current patient does not have Y-shaped cataracts that were observed in the original patients. However, he shows the double-ring sign in the eyes, which is caused by aberrant collagen layers in the lens capsule (7). The current case likely involves a second mutant allele that influences the different manifestations of the phenotypes.

Our data imply that CLSD may be genetically heterogeneous and that more COPII related genes responsible for craniofacial development will be uncovered in the future. We propose that CLSD may be more common than previously thought and should be considered in the evaluation of patients with late closing fontanels and hypertelorism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the family for donating samples and time for the participation in this study. We thank Dr. Ralph Lachiman of the International Skeletal Dysplasia registry at the Cedar-Sinai Hospital of Los Angeles for his detailed and critical review of the skeletal films. This work is supported in part by Children’s Miracle Network (CMN) endowed chair in Pediatric Genetics and by a National Institute of Health (NIH) grant R01 DE016886 from NIDCD/NIH to SAB. JK is supported in part by University of California Davis Academic Senate Faculty Research Award. RS is supported in part by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests Statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chai Y, Maxson RE., Jr Recent advances in craniofacial morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2353–2375. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyadjiev SA, Justice CM, Eyaid W, et al. A novel dysmorphic syndrome with open calvarial sutures and sutural cataracts maps to chromosome 14q13-q21. Hum Genet. 2003;113:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0932-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyadjiev SA, Fromme JC, Ben J, et al. Cranio-lenticulo-sutural dysplasia is caused by a SEC23A mutation leading to abnormal endoplasmic-reticulum-to-Golgi trafficking. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1192–1197. doi: 10.1038/ng1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wall FE, Henkel RD, Stern MP, et al. An efficient method for routine Epstein-Barr virus immortalization of human B lymphocytes. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1995;31:156–159. doi: 10.1007/BF02633976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim J, Hamamoto S, Ravazzola M, et al. Uncoupled packaging of amyloid precursor protein and presenilin 1 into coat protein complex II vesicles. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7758–7768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411091200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fromme JC, Ravazzola M, Hamamoto S, et al. The genetic basis of a craniofacial disease provides insight into COPII coat assembly. Dev Cell. 2007;13:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ataka S, Kohno T, Kurita K, et al. Histopathological study of the anterior lens capsule with a double-ring sign. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:245–249. doi: 10.1007/s00417-003-0814-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlman M. Perlman syndrome: familial renal dysplasia with Wilms tumor, fetal gigantism, and multiple congenital anomalies. Am J Med Genet. 1986;25:793–795. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320250418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fine BA, Lubinsky M. Craniofacial and CNS anomalies with body asymmetry, severe retardation, and other malformations. J Clin Dysmorphol. 1983;1:6–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bi X, Mancias JD, Goldberg J. Insights into COPII coat nucleation from the structure of Sec23.Sar1 complexed with the active fragment of Sec31. Dev Cell. 2007;13:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher LW, Lindner W, Young MF, et al. Synthetic peptide antisera: their production and use in the cloning of matrix proteins. Connect Tissue Res. 1989;21:43–48. doi: 10.3109/03008208909049994. discussion 49–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murshed M, Harmey D, Millan JL, et al. Unique coexpression in osteoblasts of broadly expressed genes accounts for the spatial restriction of ECM mineralization to bone. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1093–1104. doi: 10.1101/gad.1276205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saito A, Hino S, Murakami T, et al. Regulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress response by a BBF2H7-mediated Sec23a pathway is essential for chondrogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1197–1204. doi: 10.1038/ncb1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts B, Clucas C, Johnstone IL. Loss of SEC-23 in Caenorhabditis elegans causes defects in oogenesis, morphogenesis, and extracellular matrix secretion. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4414–4426. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-03-0162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lang MR, Lapierre LA, Frotscher M, et al. Secretory COPII coat component Sec23a is essential for craniofacial chondrocyte maturation. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1198–1203. doi: 10.1038/ng1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Townley AK, Feng Y, Schmidt K, et al. Efficient coupling of Sec23-Sec24 to Sec13-Sec31 drives COPII-dependent collagen secretion and is essential for normal craniofacial development. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3025–3034. doi: 10.1242/jcs.031070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bi X, Corpina RA, Goldberg J. Structure of the Sec23/24-Sar1 pre-budding complex of the COPII vesicle coat. Nature. 2002;419:271–277. doi: 10.1038/nature01040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.